Immunosuppressant treatments are being used frequently in the context of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. These treatments can predispose to the reactivation of infections that had remained asymptomatic.

We present the case of a 70-year-old male patient who sought treatment at a tertiary hospital in the Community of Madrid in April 2020 in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The patient’s only medical history was hypertension, in treatment with losartan-hydrochlorothiazide. The patient was of Ecuadorian origin, resident in Madrid since 2008, returning to his country for just a single visit in 2016. Specifically, the patient had lived in the rural Guayaquil area, and during his childhood had performed agrarian tasks and often walked barefoot. He later worked as a metalworker in a car factory, an occupation he currently continues in Spain. He came to the hospital presenting with a dry cough, fever, dyspnoea and chest pain. The physical examination revealed constant dry rales up to the middle fields: RR: 34 bpm, baseline O2Sat: 92%. Blood tests were ordered, which most notably revealed: elevated transaminases, leukocytes 8690/µl, neutrophils 7680/µl (88.4%), lymphocytes 590/µl (6.8%), monocytes 360/µl (4.1%), eosinophils 10/µl (0.1%), basophils 10/µl (0.1%), haemoglobin 16 g/dl, platelets 244,000/µl. X-ray confirmed the presence of pneumonia and a nasopharyngeal swab PCR test was positive for SARS-CoV-2. For the first three days from admission he presented respiratory deterioration, developing adult respiratory distress syndrome, for which treatment was started with 250-mg boluses of methylprednisolone for five days. Tocilizumab was administered from day 6 to day 13, and anakinra on days 10–13 and 19–24. Following clinical improvement, the dose of corticosteroids was tapered, ending treatment at one month. The patient maintained a normal eosinophil count throughout his hospital stay. A Quantiferon test was ordered, with a negative result, as well as serological tests for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B and C, Leishmania and Trypanosoma cruzi all negative. A serological test was also ordered for Strongyloides stercoralis, but the test was not available at the time.

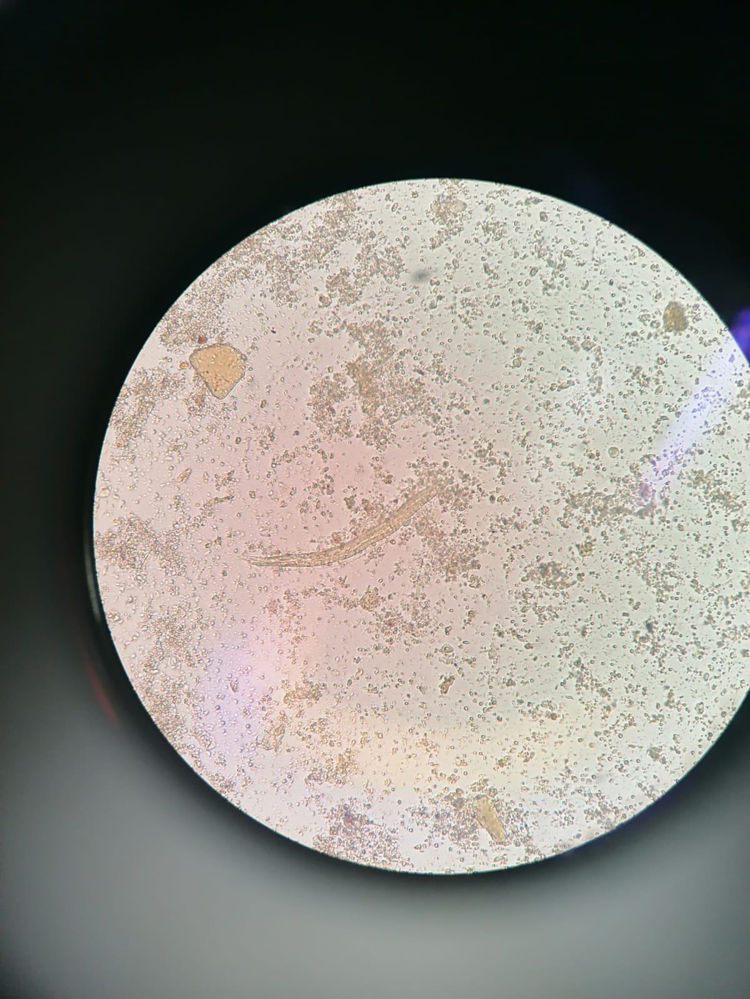

At one month after discharge, the patient began to experience epigastric abdominal pain without nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, cutaneous pruritus, or loss of weight or appetite. The respiratory symptoms had resolved. The chest X-ray showed resolution of the pneumonia. Blood tests were ordered, returning the following leukocyte count: leukocytes 23,170/µl, neutrophils 3000/µl (12.7%), lymphocytes 5900/µl (25.3%), monocytes 900/µl (3.9%), eosinophils 13,300/µl (57.3%), basophils 200/µl (0.8%). Repeat serological tests were ordered, which were all negative except the one for Strongyloides, which was positive. The fresh stool analysis confirmed the presence of Strongyloides sp. larvae (Fig. 1). In view of the diagnosis, the patient received albendazole 400 mg/12 h for three days, with resolution of the digestive symptoms. Follow-up blood tests were performed several weeks later, with improvement of the eosinophilia. However, given that it did persist, new stool samples were requested, in which Strongyloides sp. larvae were once again observed. Given the treatment failure, treatment with ivermectin was initiated, with resolution of the clinical picture.

The diagnosis of strongyloidiasis is established by visualising Strongyloides larvae. This infection is often underdiagnosed due to the low sensitivity of the diagnostic techniques, but serology is sufficient to rule out the diagnosis1. Although in our setting such cases are usually imported, there is also endemic transmission in Spain2. Most imported cases come from South America3, with Ecuador being one of the countries with the highest prevalence4.

Strongyloides is the only nematode capable of causing autoinfection in the host, leading to chronic parasitic infection lasting decades5. In immunocompetent patients, infection is often asymptomatic5. More than 80% of patients with imported strongyloidiasis present eosinophilia as the only manifestation. From this perspective, the presence of eosinophilia in a patient from South America should make us suspect Strongyloides infection, among other possible diagnoses3.

The symptoms, when they appear, are epigastric pain, skin lesions and/or eosinophilia6. In immunosuppressed patients, hyperinfection syndrome can arise, with multi-organ involvement and high mortality1. The administration of glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressants is a risk factor for the development of symptoms6,7. The treatment of choice8 is ivermectin (accessible on request as a foreign medicinal product not authorised in Spain), with albendazole being a less effective alternative (available in normal pharmacies). Given the exceptional circumstances, in our case albendazole was chosen as the first-line therapy because it was easy for the patient to acquire.

Our patient presented a reactivation of Strongyloides sp., probably in relation to prolonged corticosteroid administration. In clinical pictures of severe pneumonia due to COVID-19, other immunosuppressant drugs are also being used, such as tocilizumab or anakinra, which has been linked to an increase in the risk of opportunistic infections9. In general, a parasite study and eradication is recommended in those patients with a history of living in or travelling to endemic areas10. Moreover, screening needs to be carried out for latent infections (tuberculosis, hepatitis B) if immunosuppressant treatments are to be administered11. Organ transplant guidelines12 include the study of parasitic infections in patients from endemic areas. For these reasons, it would be interesting to carry out screening for latent infections in patients who are going to receive immunosuppression treatment in the context of this pandemic13.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and received no funding to conduct this study.

Please cite this article as: Pintos-Pascual I, López-Dosil M, Castillo-Núñez C, Múñez-Rubio E. Eosinofilia y dolor abdominal tras una neumonía grave por enfermedad por coronavirus 19. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:478–480.