Abducens nerve palsy is considered the most common cranial nerve paralysis in childhood.1 The most frequent aetiology is traumatic or tumoural.2 Knowledge of the anatomy of the nerve allows the lesion to be located and its study to be focused. After emerging from the protuberance at the pontobulbar junction, it ascends ventrally to the brainstem, until it rotates at the apex of the petrous temporal bone under the petroclinoid ligament. It penetrates the cavernous sinus, enters the orbit through the superior orbital fissure and remains in a lateral position until it reaches the lateral rectus muscle.2 This long path means that the abducent nerve can be injured directly by focal processes or indirectly in relation to the intracranial hypertension that pulls on the nerve. In this situation, the paralysis of the nerve, whether uni- or bilateral, is a false localising sign, since the dysfunction is distant in relation to the expected location, defying the clinical-anatomical correlation on which the neurological examination is based.3

We present a case of meningococcal meningitis B whose onset was bilateral abducens nerve palsy related to intracranial hypertension.

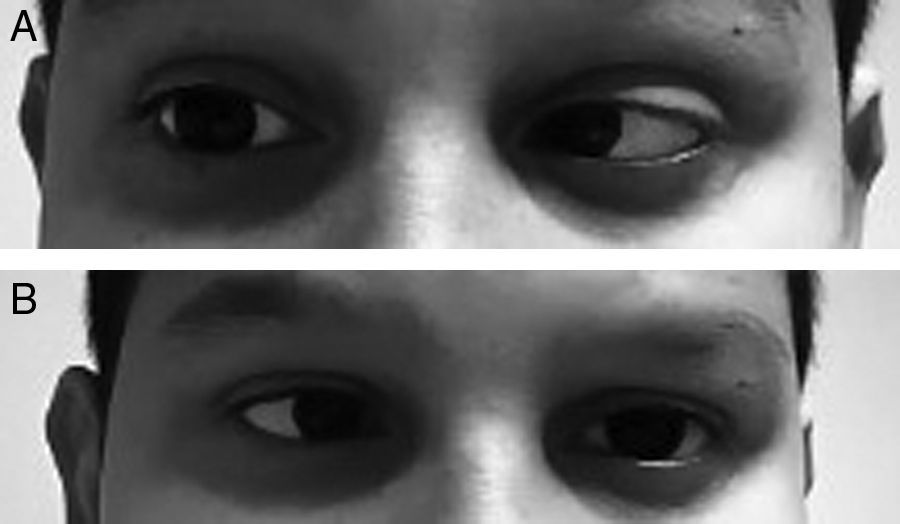

An 11-year-old male who visited the emergency department because of a headache which developed over 24hours and isolated fever peak of 39°C on the previous day. As the only personal history, he had episodic headaches with nonspecific characteristics, but this time the pain was more intense and accompanied by photophobia, sonophobia and dizziness, without frank instability. In addition, he mentioned cervicalgia that he justified by a poor posture. Neurological examination was completely normal, with no meningeal signs, and the vital signs showed a temperature of 37.1°C and blood pressure of 116/74. Pain improved after the administration of oral metamizole and he was discharged with the diagnosis of migraine headache. The next day he returned to the emergency department due to a recurrence of the headache and double vision in the horizontal plane. It was not accompanied by nausea or vomiting. The overall examination was normal, without showing any cutaneous lesions. On neurological examination the presence of bilateral abducens nerve palsy (Fig. 1A and B) and positive meningeal signs were noted. The fundus of the eye did not show papilledema and the level of consciousness was normal. The temperature was 37.2°C. Blood analysis showed 14,300 leukocytes/μl (11,500 neutrophils/μl) and CRP of 20mg/dL. The cranial CT scan was normal and a lumbar puncture was performed, which obtained a whitish cloudy liquid with an opening pressure of 52cm of H2O, with 3702cells/mm3 (80% PMN), 18mg/dL of glucose (capillary glycaemia 92mg/dL) and 0.54g/L of proteins. Blood cultures were taken, and empiric treatment with ceftriaxone (100mg/kg/day) and dexamethasone (0.6mg/kg/day distributed in 4 doses). The Gram stain did not show pathogens, but in the LCR culture a Neisseria meningitidis of the serotype B grew. The cranial NMR showed a leptomeningeal uptake of gadolinium within the sulci of both hemispheres, as expected from purulent meningitis. At 48hours of evolution the patient recovered complete mobility of the left side of the abducens nerve, and the right side 5 days later, being discharged with a normal neurological examination after completing antibiotic treatment.

Invasive meningococcal infection is commonly associated with serotypes A, B and C of Neisseria meningitidis. Meningitis is its most common form of presentation, reaching 80% of the cases.4 The clinical course is usually fulminant, and is characterised by high fever, headache and neck stiffness. These manifestations vary depending on microbiological factors (bacterial load and circulating endotoxin) and the host (innate and acquired immune response). This could explain the exceptional nature of the presented case, since it did not begin with the typical triad, but directly with an intracranial hypertension syndrome with abducens nerve palsy, with insufficient evolution time to develop papilledema. The rapid resolution of the patient's symptoms and the absence of contrast uptake in the cranial NMR ruled out that the neuropathy was due to direct invasion. The cranial nerves may be affected in the course of bacterial meningitis. In a series of 110 cases of invasive meningococcal disease, the proportion of patients with a lesion of the abducent nerve reached 4.5%.5 However its involvement is not expected as an isolated clinical onset, with no other signs of suspected infection. Hence the importance of detailed neurological examination in the diagnostic approach to the patient. In the event of abducens nerve palsy, whether uni- or bilateral, it is necessary to consider the possibility of intracranial hypertension and to request the necessary complementary tests (neuroimaging and lumbar puncture) to establish its aetiology.

Please cite this article as: Camacho Salas A, Rojo Conejo P, Núñez Enamorado N, Simón de las Heras R. Parálisis bilateral del VI par craneal como manifestación inicial de la meningitis meningocócica. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:388–389.