There are several controversies regarding the diagnostic tests and management of central precocious puberty (CPP). The aim of this study is to present the experience acquired in a group of girls with CPP treated with triptorelin, and to analyze the auxological characteristics and diagnostic tests.

Material and methodsAn observational, retrospective study in a group of 60 girls with CPP was conducted between January 2010 and December 2017. Sociodemographic, auxological and hormonal data were recorded at diagnosis, and pelvic ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging of the head were performed. Girls were treated with triptorelin and monitored after treatment discontinuation until menarche.

ResultsAt treatment start, chronological age and bone age were 7.7±0.7 and 9.7±0.8 years respectively, and growth velocity was 8.3±1.6cm/year. Target height was 161.1±5.8cm. Peak LH level after stimulation was 16.6±12.1IU/l. Ovarian volumes were greater than 3mL in 35% of cases. MRI of the head was pathological in seven girls (11.7%). At treatment completion, chronological age and bone age were 10.3±1.1 and 11.2±0.8 years respectively, and growth velocity was 4.7±1.4cm/year. At the age of menarche (11.9±0.9 years), height was 157.5±5.7cm.

ConclusionsTreatment of CPP with triptorelin appears to be beneficial. The possibility to block pubertal development and slow skeletal maturation allows patients to reach their target height. However, individualized auxological monitoring would be mandatory.

Existen diversas controversias respecto a las pruebas diagnósticas y tratamiento de la pubertad precoz central (PPC). El objetivo de este estudio es exponer las experiencias adquiridas en un grupo de niñas con PPC tratadas con triptorelina, analizándose las características auxológicas y pruebas diagnósticas.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo en un grupo de 60 niñas con PPC atendidas entre 2010 y 2017. Al diagnóstico se registraron datos sociodemográficos, auxológicos y hormonales, realizándose ecografía pélvica y resonancia craneal. Fueron tratadas con triptorelina, y tras su retirada fueron seguidas hasta la menarquia.

ResultadosAl iniciar el tratamiento, la edad cronológica y edad ósea eran de 7,7±0,7 y 9,7±0,8 años, respectivamente (media±DE), con una velocidad de crecimiento de 8,3±1,6cm/año. La talla diana era de 161,1±5,8cm. El pico de LH tras estimulación era de 16,6±12,1UI/l. El volumen ovárico era superior a 3 cc en el 35% de los casos. La resonancia magnética craneal fue patológica en 7 casos (11,7%). Al final del tratamiento, la edad cronológica y la edad ósea eran de 10,3±1,1 y 11,2±0,8 años, respectivamente, con una velocidad de crecimiento de 4,7±1,4cm/año. A la edad de la menarquia (11,9±0,9 años), la talla era de 157,5±5,7cm.

ConclusionesEl tratamiento de la PPC con triptorelina parece resultar beneficioso. La posibilidad de bloquear el desarrollo puberal y ralentizar la maduración ósea permiten que las pacientes alcancen su talla diana. No obstante, sería preceptiva una monitorización auxológica personalizada.

Precocious puberty is classically defined as the progressive onset and development of sexual characteristics before 8 years of age in girls and 9 years of age in boys, and is associated with an advancement of bone age and an accelerated growth rate.1–3

Despite advances in the study of central precocious puberty (CPP), there is still controversy regarding the suitability of the complementary tests required for establishing its diagnosis and, especially, for starting and discontinuing treatment. Although luteinizing hormone (LH) measurement after stimulation is accepted as the reference diagnostic test, advances in immunoassay techniques have led different authors to consider the usefulness of basal LH as a screening method.4–9 With regard to imaging tests, although pelvic ultrasound is regarded as essential, there is no agreement concerning the anatomical variable offering the best diagnostic performance.10–12 The routine prescription of neuroimaging studies in girls with central precocious puberty has been a subject of considerable debate.3,13,14 In addition, the lack of randomized clinical trials with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (aLHRH) in the treatment of CPP makes scientific evidence in this field largely dependent upon descriptive studies (large series, meta-analyses, etc.).3,15–18

The purpose of this study was to report on the experience gained in a group of girls with CPP who were treated with triptorelin, and to analyze the results of the diagnostic tests and the time course of the clinical–auxological characteristics.

Material and methodsA retrospective, longitudinal descriptive study was made, including all girls under 8 years of age diagnosed with CPP, with no exclusion of any case, who were seen in one of the outpatient clinics of the Pediatric Endocrinology Unit of Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (Spain) during the period between January 2010 and December 2017.

On the first visit we compiled sociodemographic (gender, ethnicity and/or continent of origin, adoption status), familial (paternal/maternal height, maternal age at menarche) and clinical–auxological data (age at symptoms onset, weight and height, the body mass index [BMI], bone age and growth rate). Target height and predicted adult height were calculated. All patients underwent basal measurements of estradiol, LH and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and FSH and LH measurements were made four hours after the intravenous administration of 500μg of leuprorelin using an immunochemiluminescence technique. A peak LH cut-off value of 5IU/l was regarded as diagnostic.4 Imaging studies were also performed: pelvic ultrasound, where an ovarian volume of ≥3cm3 was considered indicative of activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis,10 and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Following the diagnosis, intramuscular triptorelin was prescribed as a monthly depot formula (80mg/kg/dose), and evolutive follow-up was performed (semestrial controls), including the following variables: chronological age, triptorelin dose, weight and height, the BMI, bone age, growth rate and predicted adult height.

The patients were monitored periodically after treatment discontinuation until menarche occurred, the following variables being recorded: age at menarche, time from treatment completion to menarche, and height at the time of menarche.

Weight and height were recorded in underwear and barefoot. Weight was measured using an Año-Sayol scale with a reading range of 0–120kg and a precision of 100g, while height was measured using a Holtain wall stadiometer recording from 60 to 210cm, with a precision of 0.1cm. Bone age and predicted adult height were calculated using the RUS-TW2 method.

The Z-scores corresponding to weights, sizes, the BMI with respect to chronological age and growth rate were calculated using the Nutritional Application of the Spanish Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (available at http://www.gastroinf.es/nutritional/), using as reference the growth tables of Ferrández et al. (Centro Andrea Prader, Zaragoza, 2002).19

Results are reported as percentages (%) and mean±standard deviation (SD). The statistical analysis (descriptive statistics, Student t-test, analysis of variance [ANOVA] and Pearson's correlation test) was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

In all cases, the parents and/or legal guardians were informed and gave their consent to participation in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, and abided with the ethical standards established in the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent amendments.

ResultsThe study sample consisted of 60 girls between 5.4 and 7.6 years of age. Breast buds were present in all of them, either bilaterally (n=56) or unilaterally (n=4). Pubic (n=12) or axillary (n=6) hair was much less prevalent.

Most of the patients (76.7%; n=46) were European (Caucasian), while the others were from different continents: 7 from Africa (11.7%), 6 from South America (10%) and one from Asia (1.6%). Seven of the girls (11.7%) were adopted.

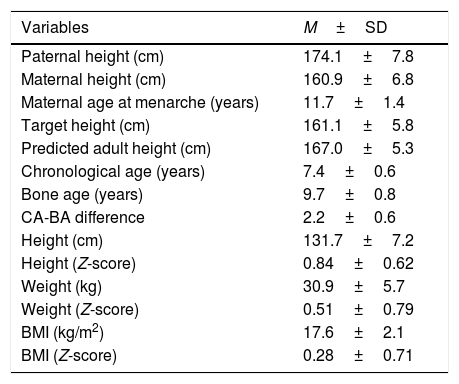

Table 1 shows the mean values corresponding to the familial and personal auxological variables recorded on the first visit. The predicted adult height significantly exceeded the target height (p<0.05).

Mean values of the familial and personal auxological variables recorded on the first visit of the study.

| Variables | M±SD |

|---|---|

| Paternal height (cm) | 174.1±7.8 |

| Maternal height (cm) | 160.9±6.8 |

| Maternal age at menarche (years) | 11.7±1.4 |

| Target height (cm) | 161.1±5.8 |

| Predicted adult height (cm) | 167.0±5.3 |

| Chronological age (years) | 7.4±0.6 |

| Bone age (years) | 9.7±0.8 |

| CA-BA difference | 2.2±0.6 |

| Height (cm) | 131.7±7.2 |

| Height (Z-score) | 0.84±0.62 |

| Weight (kg) | 30.9±5.7 |

| Weight (Z-score) | 0.51±0.79 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.6±2.1 |

| BMI (Z-score) | 0.28±0.71 |

CA: chronological age; BA: bone age; BMI: body mass index; M±SD: mean±standard deviation.

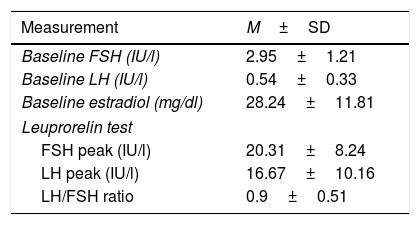

Table 2 shows the mean baseline values corresponding to FSH, LH and estradiol, and the FSH and LH values and the LH/FSH ratio after the leuprorelin test. The LH/FSH ratio was over 0.6 after leuprorelin stimulation in 61.4% of the cases (n=35). There was no correlation between the baseline LH levels and peak LH surge or the LH/FSH ratio after stimulation.

Mean FSH, LH and estradiol values at baseline and after stimulation with leuprorelin.

| Measurement | M±SD |

|---|---|

| Baseline FSH (IU/l) | 2.95±1.21 |

| Baseline LH (IU/l) | 0.54±0.33 |

| Baseline estradiol (mg/dl) | 28.24±11.81 |

| Leuprorelin test | |

| FSH peak (IU/l) | 20.31±8.24 |

| LH peak (IU/l) | 16.67±10.16 |

| LH/FSH ratio | 0.9±0.51 |

M±SD: mean±standard deviation.

Pelvic ultrasound revealed a maximum ovarian volume of less than 3cm3 in 65.5% of the patients (n=39), while the volume exceeded this figure in the remaining 35% (n=21).

The brain MRI study proved normal in 83.3% of the cases (n=53), while the remaining 7 cases showed a range of findings: pineal gland cyst (2 cases); arachnoid cyst at the midline of the posterior fossa (one case); right parasagittal arachnoid cyst at parietal level (one case); pseudonodular thickening of the pituitary stalk (one case); residual hydrocephalus after surgical resection of a cerebellar tumor (one case); and hydrocephalus secondary to perinatal disease (one case).

Treatment with intramuscular triptorelin in its monthly depot formula was prescribed in 96.7% of the patients (n=58), the mean starting dose being 81.3±0.7μg/kg, with a mean duration of treatment of 2.5±0.9 years. Two patients were not treated due to family decision. One of them experienced menarche at 9.8 years of age (bone age: 13.4 years), and currently at 14.1 years of age her height is 147cm (target height: 161.5cm). The other patient experienced menarche at 10.7 years of age (bone age: 13.1 years), and currently at 13.4 years of age, her height is 160cm (target height: 158.5cm).

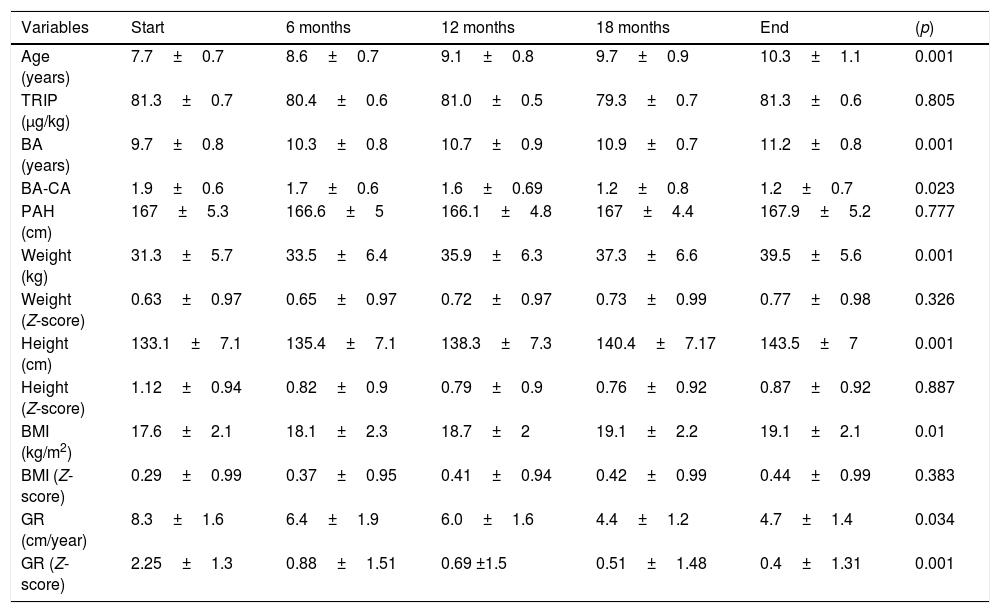

Table 3 shows the mean values of the patient auxological variables recorded on the first visit and over the course of treatment with triptorelin. The difference between bone age and chronological age decreased significantly (p=0.023) during the course of treatment. Both the triptorelin doses and the predicted adult height remained constant throughout treatment. Although the absolute patient weight, height and BMI values increased significantly, there were no significant differences between the mean values corresponding to weight (Z-score), height (Z-score) and the BMI (Z-score) with respect to chronological age. The growth rate decreased significantly (p=0.001) during treatment.

Mean values (M±SD) of the auxological variables recorded from the start to the end of treatment with triptorelin.

| Variables | Start | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | End | (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 7.7±0.7 | 8.6±0.7 | 9.1±0.8 | 9.7±0.9 | 10.3±1.1 | 0.001 |

| TRIP (μg/kg) | 81.3±0.7 | 80.4±0.6 | 81.0±0.5 | 79.3±0.7 | 81.3±0.6 | 0.805 |

| BA (years) | 9.7±0.8 | 10.3±0.8 | 10.7±0.9 | 10.9±0.7 | 11.2±0.8 | 0.001 |

| BA-CA | 1.9±0.6 | 1.7±0.6 | 1.6±0.69 | 1.2±0.8 | 1.2±0.7 | 0.023 |

| PAH (cm) | 167±5.3 | 166.6±5 | 166.1±4.8 | 167±4.4 | 167.9±5.2 | 0.777 |

| Weight (kg) | 31.3±5.7 | 33.5±6.4 | 35.9±6.3 | 37.3±6.6 | 39.5±5.6 | 0.001 |

| Weight (Z-score) | 0.63±0.97 | 0.65±0.97 | 0.72±0.97 | 0.73±0.99 | 0.77±0.98 | 0.326 |

| Height (cm) | 133.1±7.1 | 135.4±7.1 | 138.3±7.3 | 140.4±7.17 | 143.5±7 | 0.001 |

| Height (Z-score) | 1.12±0.94 | 0.82±0.9 | 0.79±0.9 | 0.76±0.92 | 0.87±0.92 | 0.887 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.6±2.1 | 18.1±2.3 | 18.7±2 | 19.1±2.2 | 19.1±2.1 | 0.01 |

| BMI (Z-score) | 0.29±0.99 | 0.37±0.95 | 0.41±0.94 | 0.42±0.99 | 0.44±0.99 | 0.383 |

| GR (cm/year) | 8.3±1.6 | 6.4±1.9 | 6.0±1.6 | 4.4±1.2 | 4.7±1.4 | 0.034 |

| GR (Z-score) | 2.25±1.3 | 0.88±1.51 | 0.69 ±1.5 | 0.51±1.48 | 0.4±1.31 | 0.001 |

BA: bone age; BMI: body mass index; M±SD: mean±standard deviation; PAH: predicted adult height; TRIP: triptorelin; GR: growth rate.

The mean age at menarche was 11.9±0.9 years. The mean time which elapsed from the end of treatment to the onset of menarche was 18.3 months (range: 12–28 months). The mean height at menarche was 157.5±4.8cm. The mean growth rate between treatment completion and menarche was 9.3±3.1cm/year, and the mean height increment during this period was 13.9±2.6cm.

DiscussionThe experience gained in this study indicates that the diagnosis of precocious puberty ultimately continues to be determined by stimulation testing with GnRH (or LHRH analogs), because the existing complementary tests (basal LH and/or gonadal ultrasound) lack the sensitivity and/or specificity needed to provide a firm diagnosis. The findings also suggest that treatment with triptorelin, by blocking pubertal development and slowing bone maturation, allows patients to reach their target height.

The genetic bases of precocious puberty are complex and still only partially clear. Over the last decade, mutations have been identified in different genes capable of expressing pathological sexual precocity. For example, different mutations have been reported in the MKRN3 gene and, less commonly, in the gene encoding for kisspeptin (KISS1) and its receptor (KISS1R), associated with central precocious puberty.20,21 Furthermore, a number of chromosomal abnormalities (Williams–Beuren syndrome, Silver–Russell syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome, Rett syndrome, etc.) have been reported to be variably associated with central sexual precocity.22. No molecular studies were made in our study, and in no case were dysmorphic features observed suggestive of syndromic and/or chromosomal alterations.

The measurement of LH after stimulation with GnRH (or LHRH analogs) constitutes the reference test for the diagnosis of central precocious puberty.3,5,16 However, there is controversy regarding the LH peak cut-off point beyond which the activation of puberty should be considered. Values ranging from 5 to 10IU/l are currently accepted as the cut-off point, depending on the method used (as immunochemiluminescence was used in our study, the cut-off point was 5IU/l).4 In recent years, as a result of the increased sensitivity of the techniques that quantify basal gonadotropins, debate has arisen regarding the usefulness of baseline LH as a screening test. Different cut-off points have been proposed, conditioned to the immunoassay used, with values ranging from 0.2 to 1.5IU/l. However, the variability of their sensitivity and specificity makes it difficult to differentiate between prepubertal patients and those with precocious activation of puberty, particularly in the early stages.4–9,23 As a result, most authors do not consider the measurement of baseline HL alone as a diagnostic reference test.4,6–9 Taking as reference the baseline LH cut-off points proposed by those authors that have used immunochemiluminescence-based testing (between 0.1 and 0.3IU/l),4,7,9,23 as in our laboratory, we observe that in 84.2% and 55.4% of the cases the baseline LH values were above 0.1IU/l and 0.3IU/l, respectively. This suggests the usefulness of baseline LH testing as a screening method, though without obviating the need for stimulation with GnRH. Finally, it should be noted that several authors have suggested assessment of the LH/FSH ratio after stimulation as an indicator of the start of puberty when the value exceeds 0.6 in girls. However, at present this ratio is considered to be of little diagnostic usefulness.24 In fact, in this study it was only detected in 61.4% of the cases.

Pelvic ultrasound helps in assessing the estrogenic effects upon uterine and ovarian size and morphology, and is mandatory in all cases of precocious puberty. Agreement is lacking regarding the anatomical parameter affording the greatest diagnostic advantages. While some authors report uterine volume to be the variable with the greatest sensitivity/specificity,11 others consider that an ovarian volume of over 3.1512 or 3.35cm310 is indicative of activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis. In our study, only 35% of the patients had an ovarian volume that exceeded these values. However, it should be noted that the absence of ultrasound evidence of estrogenic impregnation does not rule out the suspicion of activation of the hormonal axis, because activation is progressive and even oscillates in the first months of pubertal development.25

In males with central precocious puberty, brain MRI is mandatory because of the high prevalence of endocranial disease in these patients.3,16,26–28 However, the prescription of this technique for girls is subject to controversy. While some authors question the need to include neuroimaging studies on a routine basis in girls with CPP, particularly among those over 6 years of age,13,14 other investigators recommend the continuation of brain MRI scans in all cases, regardless of patient gender, because the clinical, auxological and hormonal characteristics of these subjects pose sensitivity/specificity difficulties as predictors in the diagnosis of CPP of organic origin.26,29 All the patients enrolled in our study underwent brain MRI. Although two patients had known neurological disease (hydrocephalus), the neuroimaging studies identified structural anomalies in 5 other girls which have been associated with sexual precocity (with the exception of the case of pituitary stalk thickening).16

The impossibility of conducting randomized controlled studies makes it difficult to establish uniform criteria for both starting and discontinuing treatment with GnRH analogs in patients with CPP. However, cumulative experience suggests that the beneficial effects of treatment upon predicted adult height appear to be inversely related to patient age at onset of the pubertal brake, and that there certainly appears to be no improvement in final height when treatment is started beyond 8 years of chronological age in girls.3,18,26,30,31 All of our patients showed signs of pubertal development before 8 years of chronological age, bilateral breast budding together with a significant increase in growth rate being the most relevant clinical signs. The advancement of bone maturation was 1.9 years above the chronological age. However, it should be noted that such bone acceleration might not yet be noticeable if consultation takes place early. In no case did the parents report emotional and/or behavioral disorders associated with precocious pubertal development, perhaps because of the promptness of the study and diagnosis, except in the two cases associated with hydrocephalus. However, this could be due to the comorbidities that may accompany the neurological disorders. Although the criteria for starting treatment with GnRH analogs usually include predicted final height as compared to target height, at the time of diagnosis the predicted height is usually seen (as in our study) to exceed the target height, conditioned - despite bone acceleration - by the significant increase in growth rate for the age of these patients.

It is known that not all patients require treatment to slow puberty and, in fact, one of the patients in our study who did not receive treatment already exceeded her target height at 13.4 years of age. Although there are no hormone measurements of usefulness in predicting accelerated pubertal development in these patients,32 it has recently been suggested that the combined analysis of anti-Müllerian hormone and inhibin B could be used as a potential biomarker of maturation acceleration in early puberty.33 However, in cases of associated organ damage, the indication of treatment with analogs is widely accepted, since these are generally cases of rapidly progressing puberty.18,31

Separate mention should be made regarding cases of adoption and/or ethnic groups different from our own. In effect, international adoption has been classified as a risk factor for pubertal precocity.3,18 In addition to probably belonging to a different ethnic group, adopted girls usually show body weight and height recovery that could imply precocious and/or advanced pubertal development. Attention should also focus more on the autochthonous growth and development characteristics of their place of origin than on those of the adoptive population. In our study, 23.3% of the girls were of non-European ethnicities. However, given the lack of validated native documentation, they were managed according to the Spanish national reference tables.

All the patients included in this study were treated with intramuscular triptorelin in its monthly depot form because of its proven tolerability, efficacy and safety. In fact, we observed the suppression of the development and/or regression of the breast bud and a decrease in growth rate to prepubertal levels. However, the salient finding was the significant slowing of the bone maturation rate experienced by these patients, making it possible for the predicted adult height to remain constant throughout the treatment period. The duration and/or withdrawal of treatment is another controversial issue. A number of variables have been proposed for establishing the optimum timing of treatment withdrawal, such as chronological age, bone age, growth rate, and the relationship between the height reached and the target height.18,20 In this regard, bone age, height reached, and particularly residual growth after treatment discontinuation are the main determining factors of adult height.17,34 Different authors thus advise treatment discontinuation when the bone age reaches 11.5 years in girls (versus 12.5 years in boys), in order to allow them to develop a “new” pubertal spurt after treatment suspension. Although analysis of the cases was carried out on a retrospective basis and there was no prior and clear definition of the criteria for withdrawal, we sought to ensure that the bone age did not exceed 11.5 years. However, we acknowledge that these patients require individualized motorization. In this study, the mean bone age at the end of treatment was 11.2 years, and the mean time which elapsed from the end of treatment to menarche was 18 months. This period was very important, because it was when any potential residual growth would occur, allowing the patients to at least achieve their target height. In fact, our study showed a mean growth rate of 9.3cm/year during this time interval, allowing for a mean height increase of 13.9cm. As a curiosity not reflected in the reviewed literature, the mean age at menarche of the girls after treatment with triptorelin was virtually analogous to the mean age at menarche of their mothers. This, and the height reached, would appear to indicate that the treatment proved beneficial for the patients.

The limitations of the present study include its retrospective nature, as well as the lack of a control group and of information on the final and/or adult height of the patients. It should be noted, however, that the mean height of the patients at the time of menarche was very close to the target height, and obviously at this point their growth and development may not have been definitively completed. It also should be noted that the predicted adult height of the patients at diagnosis and also their height at the end of the study was probably overestimated by clinical and auxological factors, though it was clear that these patients would eventually reach an adult height similar to their target height.

ConclusionsDespite the lack of randomized clinical trials with LHRH analogs – in this case with triptorelin – in central precocious puberty, their effects appear to be beneficial, since by blocking pubertal development and slowing bone maturation, they allow the patients to reach their target height. However, in view of the controversy regarding the indications for starting and suspending treatment, individualized clinical–auxological monitoring should be mandatory.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Durá-Travé T, Ortega Pérez M, Ahmed-Mohamed L, Moreno-González P, Chueca Guindulain MJ, Berrade-Zubiri S. Pubertad precoz central en niñas: estudio diagnóstico y respuesta auxológica al tratamiento con triptorelina. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:410–416.