Surgical practices constitute a common topic of complaint among medical students. The aim of this study is to analyze the type of surgical training that students receive in medical school and the impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

MethodsA survey based on the National Spanish Agency for the Quality of Evaluation and Accreditation (ANECA) guidelines was spread on social media between medical students and physicians waiting to start their residency. The time spent in surgical practices, the number of times that certain abilities were performed, and the desire of choosing a surgical specialty were analyzed.

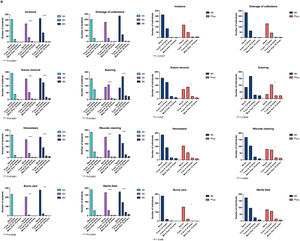

Results1053 surveys were analyzed. Significant differences between the number of months that students rotate and the number of procedures performed as they gained seniority were found. A weak positive correlation between the number of months rotating and the number of procedures performed was found. The desire of choosing a surgical specialty was not associated with the time spent in surgical practice. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has reduced the time spent in surgical practice and some of the surgical procedures performed.

ConclusionThe amount of surgical procedures performed by students is below the requirements of ANECA guidelines. A different level of dexterity between 6th year students’ group affected by SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and physicians’ group should not be expected because of the low number of procedures performed by both groups. Students’ role in the operating room and the need for different systems of skills learning should be reconsidered.

Las prácticas de pregrado suponen un tema habitual de queja entre los estudiantes de medicina. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar el tipo de formación quirúrgica en pregrado y el impacto de la pandemia de SARS-CoV-2.

MétodosSe realizó una encuesta basada en las guías de la Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad y Acreditación (ANECA). Se analizó el tiempo empleado en prácticas quirúrgicas, las veces que se practicaron ciertas habilidades y el deseo de escoger una especialidad quirúrgica.

ResultadosSe analizaron 1.053 encuestas. Se encontraron diferencias significativas entre el número de meses que rotaban los estudiantes y el número de procedimientos realizados a medida que se encontraban en un curso superior. Se encontró una débil correlación positiva entre el número de meses rotando y el número de procedimientos realizados. El deseo de elegir una especialidad quirúrgica no se asoció con el tiempo empleado en prácticas quirúrgicas. La pandemia de SARS-CoV-2 redujo el tiempo empleado en prácticas y el número de algunos procedimientos realizados.

ConclusiónLos procedimientos realizados por estudiantes son inferiores a los requerimientos de la ANECA. No existe un nivel de destreza diferente entre los alumnos de sexto afectados por el SARS-CoV-2 y los médicos graduados debido al bajo número de procedimientos realizados por ambos grupos. Se debería de reconsiderar el papel de los estudiantes en quirófano, así como nuevos métodos de enseñanza.

The absence of hands-on surgical practices is a common topic of complaint among medical students in Spain. Students claim that they are often ignored in surgical services and have adopted the term “ficus” to refer to themselves.1

All medical professionals should have an understanding of basic surgical abilities, and that can only be acquired by hands-on practice. Thus, the National Spanish Agency for the Quality Evaluation and Accreditation (ANECA) establishes on its guidelines recommendations about the surgical skills that students should learn.2

However, the medical community is concerned about the real requirements for undergraduate doctors to obtain the medical degree.1

In Spain, SARS-CoV-2 pandemic led to declare the state of alarm on March 2020 and medical schools suspended students’ practices, as in other countries.3,4

In this study, we analyze the type of surgical training that students receive and the impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in undergraduate surgical training.

MethodsSurvey designAn online survey was addressed to two groups: medical students in clinical 4th, 5th and 6th years (students’ group), and physicians waiting to start their medical residency (physicians’ group). Only students and physicians that studied in Spain were recruited.

The analyzed surgical skills on the survey were based on the ANECA guidelines.2

We selected surgical skills that were classified by ANECA as adequate to be performed by a student without supervision (burns care, wounds cleaning, hemostasis and preparation of a sterile field) and to be performed by a student under direct supervision (incisions, drainage of collections, suturing and suture removal).

Sample collectionSurveys were spread on social media (Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp) during one week in April 2020 (students’ group) and May 2020 (physicians’ group). Ninety-three percent of our study population had access to social media.5

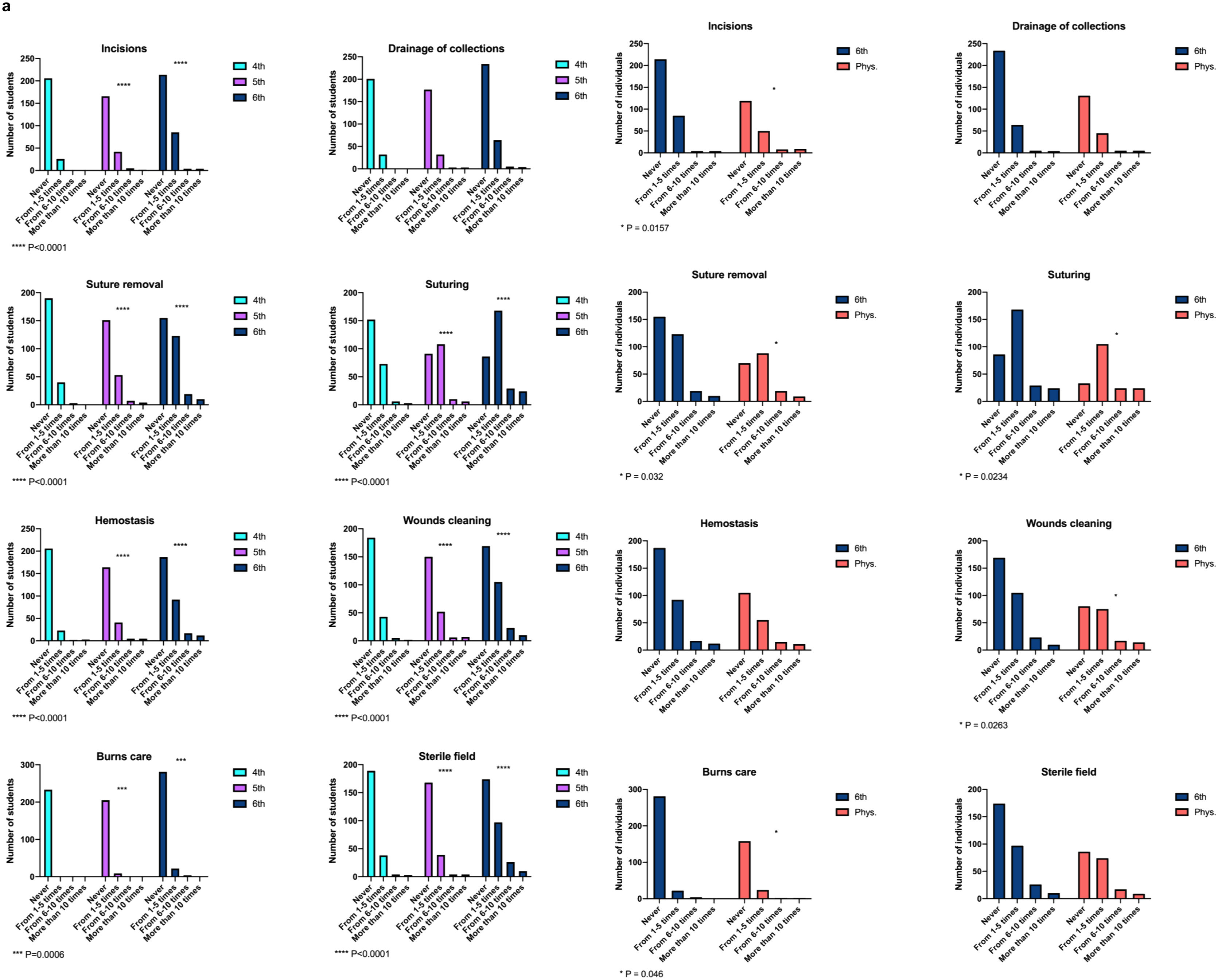

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic impact analysisSARS-CoV-2 pandemic impact on students’ surgical training was analyzed comparing the number of months that 6th year students spent into surgical rotations versus the number of times that individuals in physicians’ group did. The number of times that each procedure was performed by 6th year students and physicians was also compared.

Data management and analysisWe converted answers expressed in days and weeks in the field “how many months have you been rotating in a surgical or medical-surgical service” to months (1 week=0.24 month, 1 day=0.14 week). Answers containing intervals of a month or less in the field “how many months have you been rotating in a surgical or medical-surgical service” were included with the lower value.

Data were analyzed using the program GraphPad Prism 8, version 8.4.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, April 2020). p-Values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were summarized using means for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. D’Agostino test was performed previous to each analysis to determine whether to use a parametric or non-parametric test. The difference between the number of months rotating in each year of students’ group was calculated using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The difference between the number of months rotating in 6th year students’ group versus physicians’ group was analyzed using the U-Mann Whitney test. The difference between the number of times that each procedure was performed in each year of students’ group and the difference between the number of times that each procedure was performed in 6th year students’ group versus physicians’ group were calculated using the chi-square test. The correlation between the number of times each procedure was performed and the number of months rotating, and the correlation between the number of months rotating and the desire of choosing a surgical or medical-surgical specialty were analyzed using the Spearman correlation.

Exclusion criteriaSurveys were excluded if they met at least one of the following criteria: (a) no answer or more than one answer on any field; (b) ambiguous answers in the field “how many months have you been rotating in a surgical or medical-surgical service” (e.g. “less than a month”, etc.); (c) a time interval longer than one month (e.g. “1–3 months”).

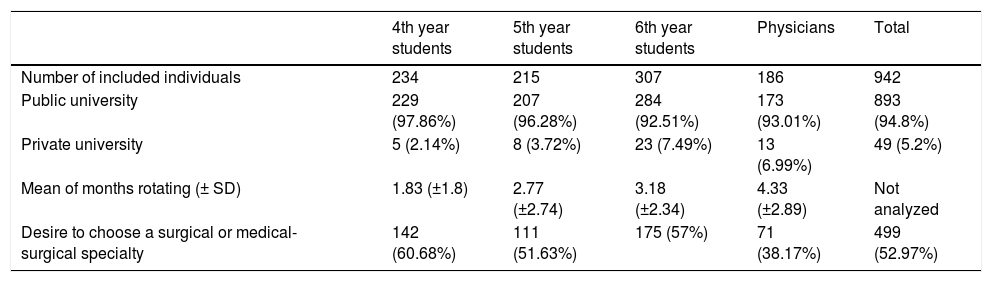

Results1053 surveys were collected. 855 surveys from the students’ group were analyzed, 99 were excluded. From the physicians’ group, 198 surveys were analyzed, 12 were excluded (Table 1).

Sample characteristics.

| 4th year students | 5th year students | 6th year students | Physicians | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of included individuals | 234 | 215 | 307 | 186 | 942 |

| Public university | 229 (97.86%) | 207 (96.28%) | 284 (92.51%) | 173 (93.01%) | 893 (94.8%) |

| Private university | 5 (2.14%) | 8 (3.72%) | 23 (7.49%) | 13 (6.99%) | 49 (5.2%) |

| Mean of months rotating (± SD) | 1.83 (±1.8) | 2.77 (±2.74) | 3.18 (±2.34) | 4.33 (±2.89) | Not analyzed |

| Desire to choose a surgical or medical-surgical specialty | 142 (60.68%) | 111 (51.63%) | 175 (57%) | 71 (38.17%) | 499 (52.97%) |

SD: standard deviation.

The mean amount of time spent at a surgical or medical-surgical service was 1.87 (±1.8) months for 4th year students, 2.77 (±2.74) months for 5th year students and 3.18 (±2.34) months for 6th year students. The difference was statistically significant (p-value<0.0001) (Table 1).

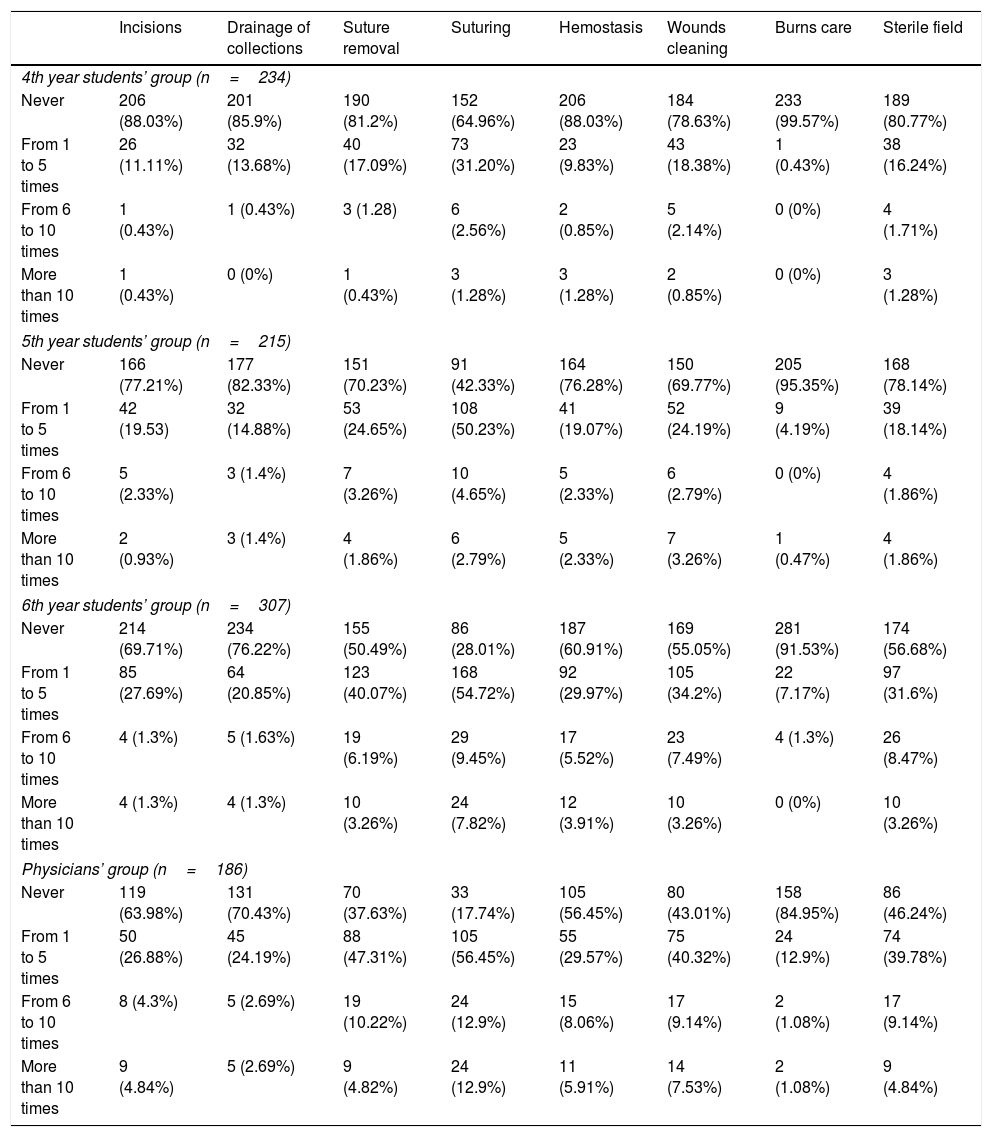

The most repeated answer for every skill and medical school year was “never” followed by “from 1 to 5 times” but for the procedure “suturing” in 5th and 6th years’ groups, that was “from 1 to 5 times” followed by “never”. There was a statistically significant increase in the number of procedures performed as students gained seniority, except for the procedure “drainage of collections” (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Surgical procedures.

| Incisions | Drainage of collections | Suture removal | Suturing | Hemostasis | Wounds cleaning | Burns care | Sterile field | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4th year students’ group (n=234) | ||||||||

| Never | 206 (88.03%) | 201 (85.9%) | 190 (81.2%) | 152 (64.96%) | 206 (88.03%) | 184 (78.63%) | 233 (99.57%) | 189 (80.77%) |

| From 1 to 5 times | 26 (11.11%) | 32 (13.68%) | 40 (17.09%) | 73 (31.20%) | 23 (9.83%) | 43 (18.38%) | 1 (0.43%) | 38 (16.24%) |

| From 6 to 10 times | 1 (0.43%) | 1 (0.43%) | 3 (1.28) | 6 (2.56%) | 2 (0.85%) | 5 (2.14%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.71%) |

| More than 10 times | 1 (0.43%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.43%) | 3 (1.28%) | 3 (1.28%) | 2 (0.85%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.28%) |

| 5th year students’ group (n=215) | ||||||||

| Never | 166 (77.21%) | 177 (82.33%) | 151 (70.23%) | 91 (42.33%) | 164 (76.28%) | 150 (69.77%) | 205 (95.35%) | 168 (78.14%) |

| From 1 to 5 times | 42 (19.53) | 32 (14.88%) | 53 (24.65%) | 108 (50.23%) | 41 (19.07%) | 52 (24.19%) | 9 (4.19%) | 39 (18.14%) |

| From 6 to 10 times | 5 (2.33%) | 3 (1.4%) | 7 (3.26%) | 10 (4.65%) | 5 (2.33%) | 6 (2.79%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.86%) |

| More than 10 times | 2 (0.93%) | 3 (1.4%) | 4 (1.86%) | 6 (2.79%) | 5 (2.33%) | 7 (3.26%) | 1 (0.47%) | 4 (1.86%) |

| 6th year students’ group (n=307) | ||||||||

| Never | 214 (69.71%) | 234 (76.22%) | 155 (50.49%) | 86 (28.01%) | 187 (60.91%) | 169 (55.05%) | 281 (91.53%) | 174 (56.68%) |

| From 1 to 5 times | 85 (27.69%) | 64 (20.85%) | 123 (40.07%) | 168 (54.72%) | 92 (29.97%) | 105 (34.2%) | 22 (7.17%) | 97 (31.6%) |

| From 6 to 10 times | 4 (1.3%) | 5 (1.63%) | 19 (6.19%) | 29 (9.45%) | 17 (5.52%) | 23 (7.49%) | 4 (1.3%) | 26 (8.47%) |

| More than 10 times | 4 (1.3%) | 4 (1.3%) | 10 (3.26%) | 24 (7.82%) | 12 (3.91%) | 10 (3.26%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (3.26%) |

| Physicians’ group (n=186) | ||||||||

| Never | 119 (63.98%) | 131 (70.43%) | 70 (37.63%) | 33 (17.74%) | 105 (56.45%) | 80 (43.01%) | 158 (84.95%) | 86 (46.24%) |

| From 1 to 5 times | 50 (26.88%) | 45 (24.19%) | 88 (47.31%) | 105 (56.45%) | 55 (29.57%) | 75 (40.32%) | 24 (12.9%) | 74 (39.78%) |

| From 6 to 10 times | 8 (4.3%) | 5 (2.69%) | 19 (10.22%) | 24 (12.9%) | 15 (8.06%) | 17 (9.14%) | 2 (1.08%) | 17 (9.14%) |

| More than 10 times | 9 (4.84%) | 5 (2.69%) | 9 (4.82%) | 24 (12.9%) | 11 (5.91%) | 14 (7.53%) | 2 (1.08%) | 9 (4.84%) |

Weak positive correlations between the number of months rotating in a surgical or medical-surgical specialty and each surgical procedure performed were found. All these correlations were statistically significant (Fig. 1).

The number of months rotating and the desire of choosing a surgical or medical-surgical specialty were not correlated (rho 0.06, p-value>0.05) (Table 1).

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic impact resultsRegarding the physicians’ group, the mean amount of time spent at a surgical or medical surgical service was 4.33 (±2.89) months. The difference between 6th year students and physicians was statistically significant (p-value<0.0001) (Table 1).

In the physicians’ group, the most repeated answer for every procedure was “never” followed by “from 1 to 5 times” except for “suture removal” and “suturing”. In those abilities, the most frequent answer was “from 1 to 5 times” followed by “never” (Table 2, Fig. 1). When compared to the 6th year students’ group, statistically significant differences were found for the procedures “incisions”, “suture removal”, “suturing”, “wounds cleaning” and “burns care” (Fig. 1).

DiscussionThough there are differences in the number of procedures performed as the students gained seniority, the fact that “never” constitutes the answer most times chosen for all the procedures except for “suturing” is a clear indicator that the training could be improved (Fig. 1). Most of these procedures can be performed in almost any surgical specialty except but for “burns care”.6–18

In none of the procedures nor the students’ groups, the sum of the answers “from 6 to 10” and “more than 10 times” reached 25% of the individuals (Table 2). We believe that a surgical procedure practiced by a physician 5 times or less is far away from the ideal, because the mean of individuals cannot get proficiency in the skill performed.19

The number of procedures performed was associated with seniority in medical school and not with the number of months spent rotating in a surgical or medical-surgical specialty (Fig. 1). A linear correlation between the number of months rotating and the number of procedures performed should be found, establishing a good “see-do” rate (Fig. 1). This should make us think about the desirable role of a student in an operating room and if a proper development of surgical practices should be performed through simulation instead.

Simulation-based education can improve technical skills without the liability risk associated with surgery and, when compared to non-simulation, better results for skills acquisition are found.20,21 Though the most attractive simulators are those with a higher cost, low-priced simulators made of cheap materials to perform certain abilities can lead to similar outcomes.21

Spanish findings do not constitute a unique case. David et al. found similar results among United Kingdom medical students. Only 17.4 percent of medical schools trained their students on knot tying and 24.7 percent of them trained them on suturing.22 Scientific societies could be a solution, through organizing courses for students.22

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic impactSARS-CoV-2 pandemic has reduced the main rotation time. A decrease of the procedures done by the 6th year students’ group versus the physicians’ group was found but for the procedures “drainage of collections”, “hemostasis” and “sterile field” (Fig. 1). However, in the physicians’ group and for all the surgical procedures, the sum of the answers “from 6 to 10” and “more than 10 times” does not reach 25% of the individuals either (Table 2). As we previously discussed, this training does not let acquire the required dexterity.19

Though these effects from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic were showed in our data, a different level of surgical dexterity between 6th year students’ group and physicians’ group should not be expected because of the low number of procedures performed by both groups.

Learning alternatives such as virtual clerkship should be considered to reduce the educational impact of the pandemic.4

Study limitationsIndividuals recruitment was performed through volunteering, consequentially there could be volunteer bias. Also, we were unable to determine the percentage of response to the survey. Seven percent of our target population may have not had access to our survey.5

ConclusionThe amount of surgical procedures performed by students is below the requirements of ANECA guidelines. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has reduced the amount of time spent rotating and some of the surgical procedures performed. A different level of dexterity between 6th year students’ group and physicians’ group should not be expected because of the low number of procedures performed by both groups. A debate on the students’ role in the operating room and the need for improvement in surgical training among medical students should be reconsidered.

Conflict of interestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.