This paper takes a closer look at factors which serve as a catalyst for transforming initially dissatisfied customers into evangelists of the firm; that is, customers who spread positive word-of-mouth about a company, its products and/or services—and recommend them to other consumers. We propose a conceptual model, rooted in relationship marketing theory, which identifies a set of factors that afford a better understanding of post-service recovery customer transformation processes. The proposed model is empirically tested in the context of mobile telecommunications services using a structural equation modeling approach. Our findings reveal that when companies are capable of designing effective service recovery processes—where customers perceive effort and justice in the outcome—initial dissatisfaction can turn to brand loyalty, long-term commitment and, above all, readiness to speak positively about the company and its products. Finally, the main implications for marketing practice are discussed.

Successfully managing customer portfolios has become increasingly complex. In many markets, aggressive price wars and marketing strategies slated to attract new customers are more and more the norm. Such strategies are not always effective, however, as they can impact reference prices and generate high consumer expectations that cannot always be met. This reality underlies Grönroos's (1996) recommendation that companies avoid focusing solely on maximizing transactions (transactional approach) and focus, rather, on building successful relationships with profitable customers (relationship-based approach). The relationship approach to marketing, then, advocates developing and nurturing successful customer-company relationships in a climate of mutual trust and commitment (Morgan and Hunt, 1994); such relationships should be long-term, as lasting relationships are more effective than short-range, aggressive actions (Grönroos, 2000)—and tend to produce more satisfactory results for both customers and companies alike (Berry, 1995; Verhoef, 2003).

Recent research accentuates the importance of taking relationship marketing to the next level—defined by a set of non-transactional customer behaviors1 that go beyond mere product repurchase and customer loyalty (van Doorn et al., 2010). Such behaviors, while not translating as immediate profits, do influence consumer perceptions of a company and its products, impact consumer purchasing patterns and enhance company image, boosting business performance in the long-term. Word-of-mouth—an informal mode of communication consisting in spreading favorable views of a company and its products, and promoting purchase among family, friends or coworkers—deserves special consideration (Kumar et al., 2010; Lim and Chung, 2011). Söderlund and Rosengren (2007) go so far as to argue that consumers rely on interpersonal information more than any other source. Word-of-mouth, then, has the potential to impact intent to purchase, customer expectations, brand opinion, and final decision to purchase (Bansal and Voyer, 2000). This type of marketing is especially attractive to firms, as customers perceive information received via word-of-mouth as being disinterested and trustworthy—in stark contrast to the opinion consumers tend to have of company-driven marketing campaigns (Herr et al., 1991). In this sense, word-of-mouth is a catalyst for the transformation of average customers into value-building evangelists: consumers eager to spread favorable views and information about a company, its products and/or services to the people around them—boosting both short-term performance and mid to long-term value creation and brand image enhancement.

Service failure is, however, inevitable. When it happens, customer satisfaction turns to dissatisfaction and the customer-firm relationship can be at stake. Hence, companies are increasingly aware of the importance of employing effective service recovery strategies with a view to regain consumer satisfaction and, ideally, play a role in transforming initially dissatisfied customers into evangelist of the firm.

The literature recognizes the importance of taking a closer look at word-of-mouth since—due to its cost effectiveness, high degree of interactivity, speed of transmission and overall efficacy—this marketing phenomenon plays a powerful role in disseminating information in consumer markets (East et al., 2007; Villanueva et al., 2008; Lim and Chung, 2011). Kumar et al. (2010, p. 303) also propose further research into word-of-mouth related behaviors which, while not likely to have an immediate impact on performance, are an asset capable of generating mid to long-term profit, enhancing brand image and allowing organizations to identify and target truly valuable customers, worthy of serious marketing investment. For the purposes of this paper, and in line with Bone (1995), we consider evangelists to be those customers which—following successful service recovery—become personally involved with the company, speak positively of the firm, its products and/or services and help attract new customers, retain existing ones and enhance overall brand image.

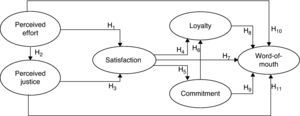

Huang (2008), despite the existence of studies analyzing some of the consequences of service recovery (Karatepe, 2006; Kau and Loh, 2006), recommends more thorough research into the behavioral implications of post-service recovery customer satisfaction. Hence, with a view to delve deeper into the impact of service recovery, we carry out a detailed analysis of the relationship between post-service recovery satisfaction and word-of-mouth. The significant value-generating potential of word-of-mouth requires further study. However, although there is widespread consensus, from a conceptual point of view, regarding the positive relationship linking post-service recovery satisfaction and word-of-mouth, there is no such consensus from a practical point of view, since a number of studies have found no empirical support for this hypothesis (Anderson, 1998; Kim and Smith, 2007). There is a clear need, therefore, to determine the nature of said relationship in today's mobile communication industry. Additionally, in line with groundbreaking recent work (Orsingher et al., 2009; Gelbrich and Roschk, 2011) we propose that satisfaction plays a mediating role for the antecedents of service recovery (perceived effort and justice) and word-of-mouth; but that loyalty and commitment will partially mediate the model as well. This latest addition constitutes an important innovation and contribution to the body of existing knowledge. On the other hand, given that a number of studies consider perceived effort or justice—not customer satisfaction—as capable of directly impacting word-of-mouth, we will contrast an alternative model which allows us to determine whether customer satisfaction should be considered a key variable in service recovery processes.

In this sense, the main objective of this study is to determine to what extent an initially dissatisfied customer—through proper management of the service recovery process (perceived effort and justice)—can be transformed into an evangelist who disseminates positive information about the company and its products via word-of-mouth.

To this end, in the next section we carry out a review of the most relevant service recovery literature with a view to gain a deeper understanding of its importance, history and possible consequences. In the following section we propose a conceptual framework that will serve as a reference model for deciphering how service recovery processes impact customer predisposition to spread positive word-of-mouth. Finally, we provide an analysis of the most relevant findings and discuss key contributions and implications of our research.

2Review of the literatureThis section aims to provide an overview of the most relevant literature on service recovery processes and their impact on word-of-mouth. The section is organized into two distinct subsections. The first takes a closer look at the antecedents to service recovery and describes the actions companies can take to reduce or reverse service failure fallout. The second focuses on the consequences of service recovery and studies the possible outcomes of successful service recovery, paying special attention to word-of-mouth behavior.

2.1Antecedents to service recovery processesAll companies—even the most prominent—make service delivery mistakes. Maxham (2001) defines service failure as a real or perceived problem occurring during customer-company interaction. In order to deal with such problems, the firm designs and implements a service recovery process—defined as the set of all actions aimed at repairing and/or compensating for damage to a customer (Bitner et al., 1990; Kelley and Davis, 1994). An added benefit of service recovery processes is their potential to generate valuable feedback, to provide a better understanding of customers and help firms learn from their mistakes (DeWitt et al., 2008).

However, as Michel and Meuter (2008) and Cambra-Fierro et al. (2011) point out, efforts to delve deeper into the service recovery concept are complicated by the fact that dissatisfied consumers often fail to file complaints—and that when they do, firms may fail to respond to them. For the purposes of this study, then, we must first establish a logical sequence: customers will file a complaint once a service failure has occurred and the firm will make every effort to respond to customer complaints and guarantee service recovery.

Despite the inherent complexity of the subject, the literature has made a major effort to study the antecedents of service recovery and how these variables impact post-service recovery customer satisfaction (Smith et al., 1999; Karande et al., 2007). Research shows that perceived effort and justice are among the most relevant factors. Maxham (2001) and Huang (2008), for instance, demonstrate that company efforts to provide prompt, fair solutions to service failures have a positive impact on customer satisfaction. Authors such as Tax et al. (1998) or De Matos et al. (2009) analyze the perceived justice variable as well, and find that customers will display a greater degree of satisfaction when they perceive fairness on the part of the firm. A number of studies have provided an in-depth, disaggregated analysis of the three dimensions of perceived justice—distributive, procedural, interactive—and their impact on satisfaction. Karatepe (2006) and Kau and Loh (2006), for example, demonstrate that all the three dimensions of perceived justice have a positive impact on customer satisfaction. Given the evidence, we consider both perceived effort and perceived justice to be key variables when it comes to measuring customer satisfaction in service recovery contexts.

2.2Positive impact of service recovery processesA number of recent studies analyze some of the consequences of service recovery processes, but fall short of providing conclusive results. Huang (2008), for example, takes a closer look at post-service recovery satisfaction; but stops there, failing to produce empirical evidence of whether this variable has an impact on customer loyalty or not. Maxham (2001) defines post-service recovery satisfaction as—depending on the experience—either a broad assessment or an evaluation on the part of customers following interaction with the firm. At the end of the study, however, Huang (2008) suggests that it would be interesting to delve deeper into the behavioral implications of post-service recovery satisfaction. To this end, we have explored how service recovery impacts perceived satisfaction (Maxham, 2001; Michel and Meuter, 2008) and may reduce customer propensity to abandon the relationship (Varela et al., 2009).

Although until very recently companies calculated the value of their customers exclusively in terms of variables with an immediate impact on business results—such as repurchase, for example—today's firms, have begun to reflect on other behaviors with longer-term effects, such as word-of-mouth (Kumar et al., 2010). Companies are beginning to realize that ignoring customer behaviors of this sort can lead to lost business opportunities due to WOM's reputational and financial impact (van Doorn et al., 2010). These behaviors may translate as truly positive switching costs for the customer and barriers to entry for the competition.

Tax et al. (1998), in their research on service recovery processes, suggest that customers who are satisfied with the way their complaint was managed are more likely to compromise. In a similar vein, Maxham (2001), Kau and Loh (2006) and De Matos et al. (2009), propose that post-service recovery satisfaction has a significant impact on customer repurchase intentions and word-of-mouth. Hence, it is through positive customer evaluation of service recovery processes that companies salvage customer satisfaction; the next step being to strive for their loyalty and attract new customers through positive WOM. Information and favorable views of the organization shared among friends, family and coworkers by satisfied customers can vitally be the number one reason behind new customer brand choice (East et al., 2008); which, in turn, can translate into a valuable customer base—from a purely transactional perspective (immediate impact on outcomes). Villanueva et al. (2008) show how customers acquired through word-of-mouth are more profitable in the long run than those who are attracted through advertising and other marketing strategies. WOM has gained increasing importance in the marketing literature due to its proven impact on business results.

Based on the existing literature, we propose that successful service recovery has a positive impact on the level of customer satisfaction—which, in turn, can have a positive impact on loyalty and commitment to the company while strengthening the company-customer relationship and generating positive word-of-mouth. Therefore, proper management of service recovery processes can turn an initially dissatisfied customer into an evangelist of the firm.

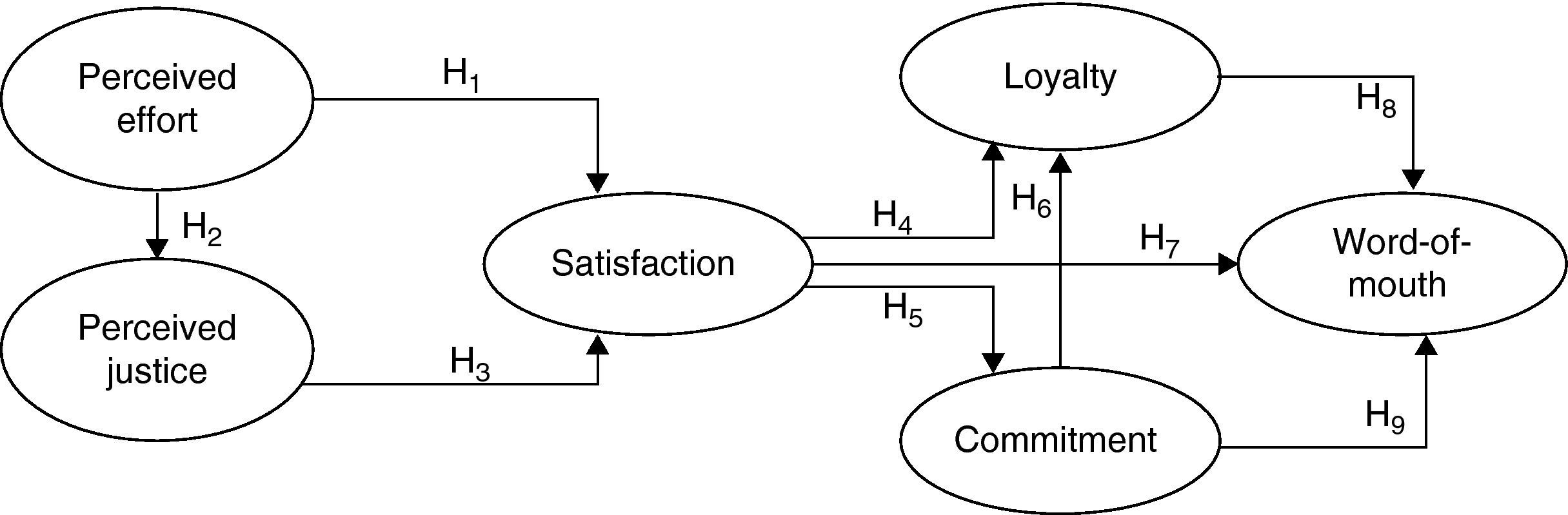

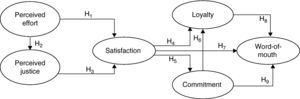

3Conceptual model and research hypothesesWith a view to accomplish our research objectives, in this section we propose a conceptual model which allows us to identify: (1) key variables in service recovery processes, and (2) the impact of service recovery strategies, paying particular attention to word-of-mouth.

To this end, we base our research on widely accepted theories found in the literature. In the first place, Relationship Marketing Theory which emphasizes the importance—for firms and customers alike—of building strong, long-lasting, mutually beneficial relationships. From a relationship marketing perspective, both stakeholders (company and customer) consider the relationship to be profitable and are willing to invest available resources (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Anderson and Weitz, 1992). Such relationships add customer value to the product or service which, in turn, will foster stronger links between company and customer and enhance the relationship.

Out second point of reference is Commitment-Trust Theory, the basis for relationship marketing (Morgan & Hunt, 1994)—which, in this context, suggests that successful service recovery may drive higher levels of consumer engagement (Kau and Loh, 2006).

Our third point of reference is Reciprocity Theory (Bagozzi, 1995). The premise here being that awareness of a firm's investment in providing solutions to service-related problems can trigger a feeling of reciprocity in customers which often leads to some sort of compensation or return investment (Palmatier et al., 2009). In other words, investment on the part of one stakeholder generates a desire to reciprocate in the other; which can translate as an investment in the relationship aimed at avoiding the feeling of guilt associated with not reciprocating to the initial investment. Thus, if companies work hard to provide just solutions to service failures, customers are likely to feel indebted and reciprocate by, for example, speaking well of the firm and recommending its products or services to potential customers via positive word-of-mouth (De Wulf et al., 2001; Palmatier et al., 2006).

The conceptual model is presented in Fig. 1. Specifically, the model proposes that post-service recovery customer satisfaction is determined by perceived effort and perceived justice. In turn, post-recovery satisfaction acts as a mediating variable in the relationship between antecedents and consequences of the service recovery process—including commitment, loyalty and positive word-of-mouth. The present study aims to use the conceptual model to determine the extent to which it is possible to turn a dissatisfied customer into an evangelist of the firm through a service recovery process that corrects the service failure and restores customer satisfaction. Thus, our hypothesis is that perceived effort and perceived justice in service recovery processes produce a higher level of satisfaction; and once satisfaction has been fully restored, customers will be more prone to speak favorably about the company and become evangelists. In this regard, worth noting are the conclusions set forth by Söderlund (2006) and Cater and Cater (2010)—who argue that loyalty, commitment and word-of-mouth are separate constructs and that approaching them jointly should be avoided. These authors defend a positive correlation between loyalty and commitment with regard to positive word-of-mouth.

3.1Antecedents to post-service recovery customer satisfaction3.1.1Perceived effortPerceived effort is defined as customer perception of a company's investment and commitment to providing solutions when service failures occur (Huang, 2008). The literature confirms that the fact that customers perceive company efforts to solve their problems can have a positive impact on customer satisfaction (Karatepe, 2006). This drives a longer term sense of connectedness to the firm and enhances post-recovery customer views of the company (McColl-Kennedy and Sparks, 2003; Guenzi and Pelloni, 2004). The role employees play in resolving the conflict is critical as well, as they are the ones who will be in direct contact with the customer throughout the entire process until the issue has been fully dealt with (De Matos et al., 2007; Huang, 2008; Johnston and Michel, 2008); more involved employees can have a positive impact on customer satisfaction and tend to motivate trust in the company and drive customer acceptance of the premise that the company is genuinely interested in seeking a solution to the service failure in question (Hocutt and Stone, 1998).

On the other hand, efforts on the part of the firm can also have an impact on perceived justice with regard to company performance when dealing with service failures (Karatepe, 2006; Ha and Jang, 2009). Customers need to know that the firm is committed to finding a fair solution to their problem. To this end, apologizing, identifying where and when the service failure took place, effectively managing response and maintaining a constant, fluid communication channel open with customers are measures which may pave the way for higher levels of distributive, procedural and interactive perceived justice process (Ha and Jang, 2009). Based on the above arguments we may propose the following hypotheses:H1 The perceived effort by customers will have a positive effect on the level of post-service recovery customer satisfaction. The perceived effort by customers will have a positive effect on the level of post-service recovery perceived justice.

The literature considers this variable as a three-dimensional concept consisting of: distributive justice, procedural justice and interactive justice (Smith et al., 1999; Sparks and Mccoll-Kennedy, 2001; Maxham and Netemeyer, 2002; Voorhees and Brady, 2005; Ambrose et al., 2007; Río et al., 2009; Varela et al., 2008). Distributive justice refers to the compensation received by consumers as a result of the service recovery process; procedural justice measures the degree of justice perceived in the service recovery process; and finally, interactional justice refers to the way employees manage interaction with customers throughout the process—their commitment to solving the problem (Chang and Chang, 2010).

Perceived justice is a key construct, especially so if we take into account that customers can be very critical of company response to service failure (Sparks and Mccoll-Kennedy, 2001). Customer perceptions with regard to service recovery have a serious impact on post-recovery satisfaction and, by extension, on future behavior; that is, customers suffering service failure will assess whether service recovery outcomes were fair or unfair and be satisfied or dissatisfied accordingly (Tax and Brown, 1998; DeWitt et al., 2008; Chang and Chang, 2010). The correlation between perceived justice and post-service recovery satisfaction has been confirmed in earlier studies (Maxham and Netemeyer, 2002; Patterson et al., 2006; Chang and Hsiao, 2008; De Matos et al., 2009; Chang and Chang, 2010). In line with the existing literature, we can formulate the following hypothesis:H3 The justice—distributive, procedural and interactive—perceived by the customer will have a positive effect on the level of post-service recovery satisfaction.

This concept refers to a positive attitude on the part of customers toward a firm's products or services—or toward the organization itself—which can translate as greater intent to purchase (Oliver, 1999). The favorable impact customer satisfaction has on loyalty has been observed by authors such as Karatepe (2006) and Chang and Chang (2010). Studies analyzing this relationship consider satisfaction to be a clear antecedent to loyalty and confirm the existence of a strong link between the two constructs (Heskett et al., 1994; Bolton, 1998; Eriksson and Löfmarck, 2000).

The underlying objective of relationship marketing is to establish and maintain long-term mutually beneficial customer-company relationships which allow for maximizing profits (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). To this end, it is crucial that customers be satisfied with the service recovery process in order to consolidate a stable, lasting relationship—as post-service recovery satisfaction will translate as customer loyalty (Gummensson, 1987; Grönroos, 2000). Effective service recovery resulting in satisfied customers, therefore, is linked to a higher degree of loyalty (Tax and Brown, 2000; Sajtos et al., 2010). Based on these findings, we propose the following hypothesis:H4 The degree of post-service recovery customer satisfaction will have a positive effect on the degree of customer loyalty.

Authors such as Garbarino and Johnson (1999) and Morgan and Hunt (1994) consider commitment as an exchange relationship which both parties feel is important to maintain; both committed parties feel the relationship is worth investing in with a view to ensure that it lasts. Recently, Kim and Brymer (2011) have shown how customer satisfaction impacts commitment—and how a positive correlation between the two variables can improve business performance. An engaged customer is key to maintaining and consolidating a long-term relationship with the company (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Bauer et al., 2002; De Wulf et al., 2001). Therefore, due to the importance of this variable, we consider customer commitment to be a consequence of the degree of post-service recovery customer satisfaction you get after a successful service recovery. We can assume that, following a successful service recovery process, a relationship with a clear emotional component will develop which can drive a desire for that said relationship to endure. Customers who are satisfied with service recovery efforts are more prone to commit to the firm and become engaged (Tax et al., 1998). Hence, we can formulate the following hypothesis:H5 The degree of post-service recovery customer satisfaction will have a positive effect on the degree of commitment to the company.

In addition, as authors like Evanchitzky et al. (2006), Cater and Cater (2010) and Bügel et al. (2011) propose, it is very likely that this desire to keep the relationship alive will translate as de facto loyalty over time; in other words, attitudes expressed as commitment become attitudes expressed through actions such as product repurchase (Cater and Cater, 2010). Based on these arguments, we can formulate the following hypotheses:H6 The degree of customer commitment will have a positive effect on the degree of customer loyalty.

This variable refers to informal communication directed at other consumers through which favorable information and/or opinions are spread about the characteristics of a product or service and/or providers2 (Westbrook, 1987). Further analysis is essential to a deeper understanding of potential impact of word-of-mouth on business performance, as clearly, customers who are satisfied with complaint management and service recovery are more prone to speak favorably about the firm to other consumers (Kau and Loh, 2006; De Matos et al., 2009). Studies by Maxham (2001) and Maxham and Netemeyer (2002), among others, defend this idea when revealing that customers—in cases where companies strive to offer a fair solution and successfully recover customer satisfaction—will be very prone to speak well of the firm. Hence, when a service failure occurs, it is essential that the organization manage the problem effectively. Furthermore, Villanueva et al. (2008) demonstrate that customers acquired through word-of-mouth are more profitable in the long run than those who are obtained through other, more expensive, forms of advertising and promotion. Therefore, with proper service recovery, companies can foster positive word-of-mouth so that current customers pass their sense of satisfaction and news of the firm's ability to effectively manage problems on to other consumers. That being said, Anderson (1998) and Kim and Smith (2007), fail to demonstrate the significance of the relationship between customer satisfaction and word-of-mouth. Thus, based on the ideas presented above and in order to clarify the lack of consensus in the literature, we propose the following hypothesis:H7 The degree of post-service recovery satisfaction will have a positive effect on the customer willingness to spread positive word-of-mouth about the company.

Additionally, other studies (e.g., Carpenter, 2008) consider it relevant to compare the relationship between satisfaction and word-of-mouth mediated by customer loyalty. This study considers hypotheses linking: (i) satisfaction to loyalty, and (ii) loyalty to word-of-mouth to be significant. Also, post-service recovery satisfaction driven commitment may impact customer willingness to speak favorably about the firm. Harrison-Walker (2001), for example, have demonstrated the positive impact customer commitment can have on word-of-mouth. Therefore, we propose to test the relationship between satisfaction and word-of-mouth mediated by concepts such as loyalty and customer commitment following successful service recovery processes. In this sense we formulate that:H8 The degree of customer loyalty will have a positive effect on the customer willingness to spread positive word-of-mouth about the company. The degree of customer commitment will have a positive effect on the customer willingness to spread positive word-of-mouth about the company.

In this section—with a view to meet research objectives and to determine whether initially dissatisfied customers can become evangelists of the firm—we will carry out an empirical test of the proposed theoretical model. To measure the reference constructs (perceived effort, perceived justice, customer satisfaction, commitment, loyalty and word-of-mouth) a questionnaire was completed by a sample selection of mobile phone users. To determine the content and the final structure of the questionnaire it was necessary to adapt previously validated, contrasted scales, to approach the reality under analysis. This study was conducted in the mobile telephone sector in Spain, as it is currently highly competitive and dynamic.3

Appendix I shows the measurement scales used in this analysis and the references used to develop initially. To do this, we performed a pre-test with students of different subjects all fourth grade and specialty of Marketing Bachelor of Business Administration. In addition, also resorted to the opinion of several experts Marketing scholars investigated the issue from three universities and national and international. They are all service users, cellular phones, in this case, and therefore have a high level of familiarity with it. Finally, the profile of the person who conducted the pre-test was representative of the population.

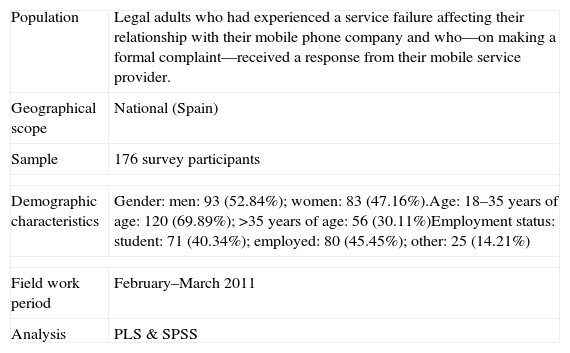

Recent work has recognized the complexity of analyzing service recovery processes because only a minority of dissatisfied customers processed a grievance (Michel and Meuter, 2008). For this reason, was subcontracted to a company specialized field work. Respondents had to be older people who have experienced first trouble with your mobile phone operator and, after placing a formal complaint, had received a response from the company. The technical data of the study are shown in Table 1.

Technical data.

| Population | Legal adults who had experienced a service failure affecting their relationship with their mobile phone company and who—on making a formal complaint—received a response from their mobile service provider. |

| Geographical scope | National (Spain) |

| Sample | 176 survey participants |

| Demographic characteristics | Gender: men: 93 (52.84%); women: 83 (47.16%).Age: 18–35 years of age: 120 (69.89%); >35 years of age: 56 (30.11%)Employment status: student: 71 (40.34%); employed: 80 (45.45%); other: 25 (14.21%) |

| Field work period | February–March 2011 |

| Analysis | PLS & SPSS |

To analyze the proposed model a structural equation modeling technique was employed using Partial Least Squares (PLS) (SmartPLS v. 2.0.M3). This methodology has recently been advocated and used in the marketing literature (Chung, 2009; Jayawardhena et al., 2009; Lindgreen et al., 2009; Reinartz et al., 2009).

Perceived effort variables, satisfaction, commitment, loyalty and word-of-mouth have been considered first-order constructs. The literature suggests sometimes that loyalty and engagement are considered multidimensional constructs. However, to adapt the questionnaires to the reality under study, the pre-test the approach recommended is shown in Appendix I. To work with the variable of perceived justice has been necessary to develop a hierarchical component analysis, as this variable represents a second-order formative construct where each of its dimensions are constructs of the first order.

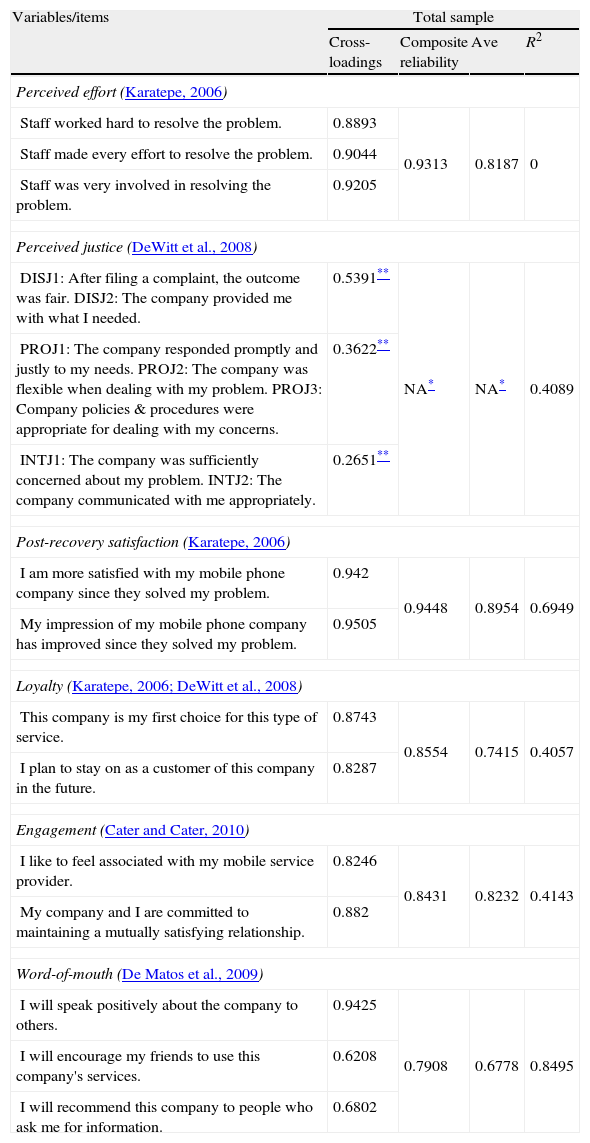

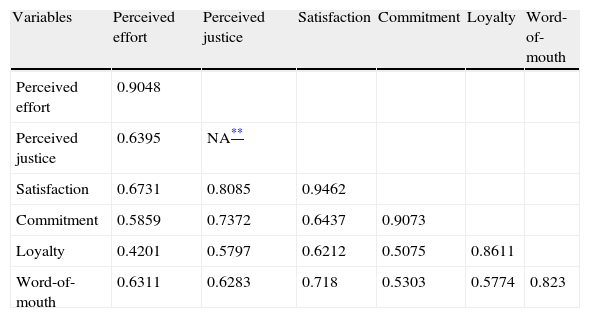

With the objective of evaluating the quality of the data obtained, an individual reliability analysis of each item relative to its construct was carried out. The results show that all the values exceed the threshold required by Carmines and Zeller (1979). The same applies when assessing the reliability of the variables using Cronbach's Alpha and composite reliability. We can confirm that all constructs are reliable and exceed the reference value (Appendix 1). In order to analyze the convergent validity we used the average variance extracted (AVE), which according to Fornell and Lacker (1981), must exceed the value of 0.5. Notably, the AVE is a measure that can only be calculated for reflective variables so post-service recovery perceived justice has been considered varying its average variance extracted will not take any value. Also, the discriminate validity was confirmed by performing a comparison of the AVE of each construct (diagonal) and correlations between variables. Thus, note that the square root of AVE is, in all cases, higher than the correlations between constructs (Appendix II).

Finally, an analysis was performed to measure the variable multicollinearity formative perceived justice. When variables are reflective this type of analysis does not make sense because what matters is that the indicators that measure the variable are highly correlated with each other. The variable perceived justice, in this study, is formed by three indicators: distributive justice and procedural interactive. Each of these indicators reflects a different aspect of the concept of justice so it is not necessary the presence of multicollinearity, i.e. that items have no correlation between them. To confirm this result we calculated the statistical collinearity, measured Inflation Variance Factor (IVF). The IVF we got with the dependent variable: procedural justice was 2.023, and really, to a value of 5, is not considered the presence of multicollinearity (Mathwick et al., 2001). So once you have shown no correlation between indicators measuring perceived justice variable, we can say that the best way to measure this construct is considering training.

5FindingsThis section presents the estimation results of the proposed model to test whether the service recovery process determines the level of post-service recovery customer satisfaction and if this, in turn, determines a higher propensity to communicate positive information about the company and its products (word-of-mouth).

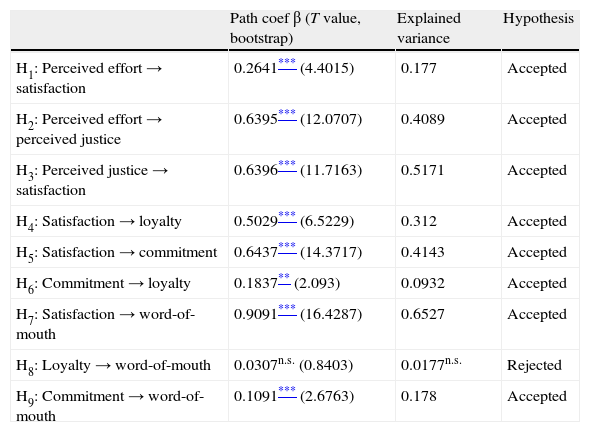

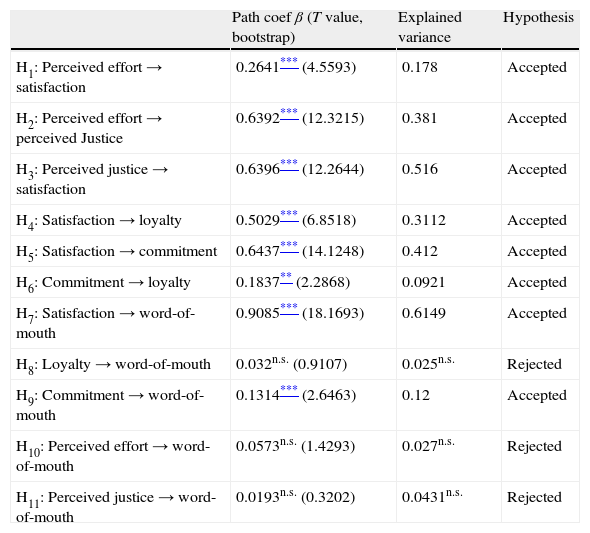

To confirm the significance of the variables we proceeded to calculate the path coefficients for the contribution of the predictor variables to the endogenous variables using for this SmartPLS, our analysis also supports t values of the parameters obtained using this technique for Bootstrap, for confirming the accuracy and stability of the estimates. Table 2 shows the significance of structural paths, the value of the explained variance and the acceptance or rejection of the hypotheses.

Results for the Structural Model.

| Path coef β (T value, bootstrap) | Explained variance | Hypothesis | |

| H1: Perceived effort→satisfaction | 0.2641*** (4.4015) | 0.177 | Accepted |

| H2: Perceived effort→perceived justice | 0.6395*** (12.0707) | 0.4089 | Accepted |

| H3: Perceived justice→satisfaction | 0.6396*** (11.7163) | 0.5171 | Accepted |

| H4: Satisfaction→loyalty | 0.5029*** (6.5229) | 0.312 | Accepted |

| H5: Satisfaction→commitment | 0.6437*** (14.3717) | 0.4143 | Accepted |

| H6: Commitment→loyalty | 0.1837** (2.093) | 0.0932 | Accepted |

| H7: Satisfaction→word-of-mouth | 0.9091*** (16.4287) | 0.6527 | Accepted |

| H8: Loyalty→word-of-mouth | 0.0307n.s. (0.8403) | 0.0177n.s. | Rejected |

| H9: Commitment→word-of-mouth | 0.1091*** (2.6763) | 0.178 | Accepted |

n.s. Not significant.

With regard to the antecedents of satisfaction with the service recovery process, we proposed a positive relationship between effort and perceived justice and customer satisfaction with service recovery (Hypothesis 1 and 3 respectively). The estimation results show that the parameters associated with both relationships are positive and significant (β=0.2641, p<0.001; β=0.6396, p<0.001), providing support for the hypotheses. That is, both history and justice-perceived effort-influencing customer satisfaction with service recovery significantly. However, these two antecedents of satisfaction are not the same level (Hypothesis 2). This work shows that the customers perceived effort significantly influences (β=0.6395, p<0.001) in their perception of justice-distributive, procedural and interactive-on management that the company has made the complaint.

In relation to the consequences of satisfaction with service recovery, we proposed a positive effect of this variable on loyalty, engagement and willingness to communicate positive information from the customer company (Hypotheses 4, 5 & 7). The results confirm the three hypotheses (β=0.5029, p<0.001; β=0.6437, p<0.001; β=0.9091, p<0.001), which leads us to conclude that getting satisfaction customer with service recovery process encourages the development of a positive attitude among customers that leads them to be more loyal to the company, to be more committed to the relationship and, above all, to communicate a word-of-mouth positive. Additionally, the results provide empirical support for the hypothesis 6, which argued for a positive association between customer engagement and loyalty degree (β=0.1837, p<0.01). Hypothesis 9 also confirms what customer engagement positively influences their willingness to spread favorable views of the company (β=0.1091, p<0.01). However, despite getting a positive coefficient in line with the prediction made, the data indicate that the effect of loyalty (H8) on the word-of-mouth is not statistically significant.

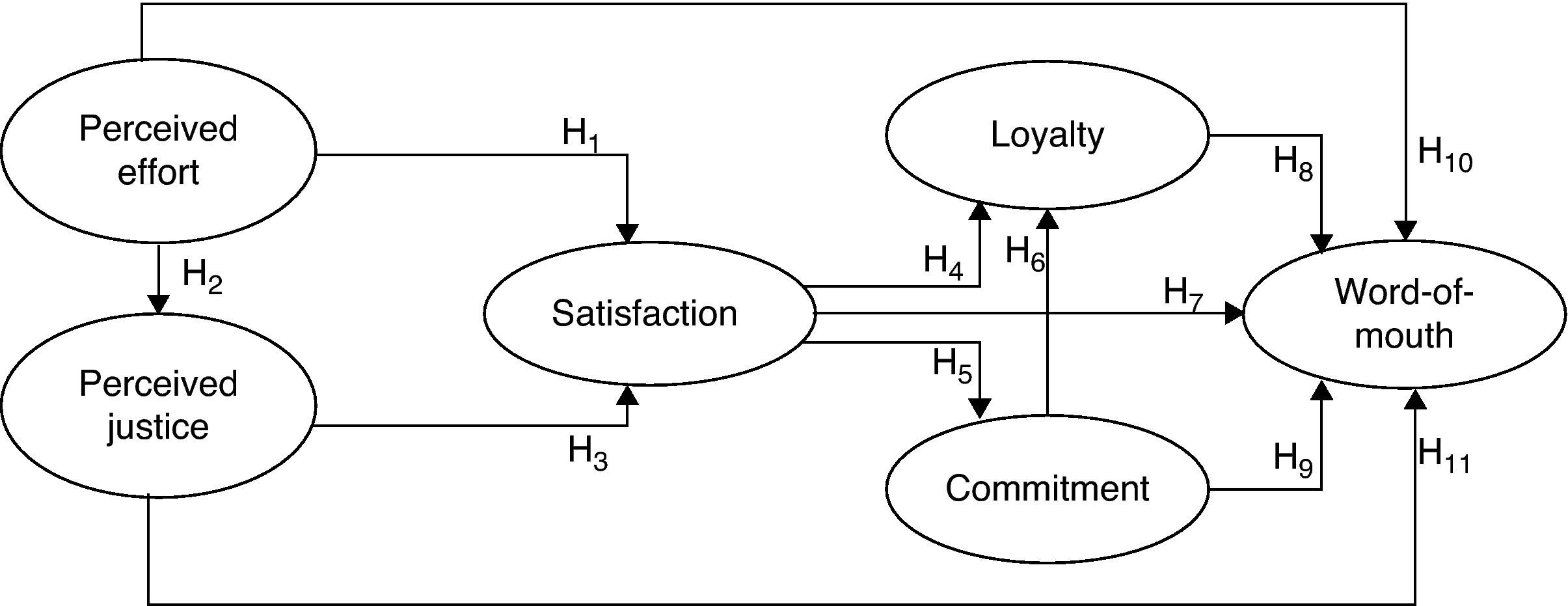

Finally, to increase the rigor of the analysis and demonstrate the validity of the proposed model to understand the process by which an initially dissatisfied customer can become a prescriber of the company, the proposed model is contrasted with the alternative model. In particular, and following some theoretical propositions related to the aforementioned theory of reciprocity (Bagozzi, 1995), could also be argued that, regardless of customer satisfaction with service recovery by the company, if customers perceive that the company strives and tries to be fair in its resolution of the problem, the customer may experience some predisposition to disseminate information or opinions favorable to their immediate environment. This may result in the existence of direct effects of perceived justice and customer effort on their willingness to issue a word-of-mouth company's positive. Fig. 2 presents the model and shows the results rival the contrast of two additional hypotheses to assess the mediating role of satisfaction in this type of process. Once submitted the rival model to empirically estimate the statistical packages SPSS and PLS, the results indicate that the direct effects between effort and perceived justice and word-of-mouth, but have a positive value, not significant from the point of statistically (Table 3). This result reveals that the company strives to offer a fair and not enough for customers to have a positive disposition to speak well of the organization. The end result of the process, the word-of-mouth, is mediated by satisfaction with service recovery, showing the superiority of the proposed model. Also in this research has considered the magnitude of the service failure as a control variable. The results indicate a value of −0.0416 and a T-statistic of 0.94. These results show that the greater the severity of the service failure the company may have more difficulties to satisfy the customer, even if the relationship turns out to be insignificant.

Results for the alternative model.

| Path coef β (T value, bootstrap) | Explained variance | Hypothesis | |

| H1: Perceived effort→satisfaction | 0.2641*** (4.5593) | 0.178 | Accepted |

| H2: Perceived effort→perceived Justice | 0.6392*** (12.3215) | 0.381 | Accepted |

| H3: Perceived justice→satisfaction | 0.6396*** (12.2644) | 0.516 | Accepted |

| H4: Satisfaction→loyalty | 0.5029*** (6.8518) | 0.3112 | Accepted |

| H5: Satisfaction→commitment | 0.6437*** (14.1248) | 0.412 | Accepted |

| H6: Commitment→loyalty | 0.1837** (2.2868) | 0.0921 | Accepted |

| H7: Satisfaction→word-of-mouth | 0.9085*** (18.1693) | 0.6149 | Accepted |

| H8: Loyalty→word-of-mouth | 0.032n.s. (0.9107) | 0.025n.s. | Rejected |

| H9: Commitment→word-of-mouth | 0.1314*** (2.6463) | 0.12 | Accepted |

| H10: Perceived effort→word-of-mouth | 0.0573n.s. (1.4293) | 0.027n.s. | Rejected |

| H11: Perceived justice→word-of-mouth | 0.0193n.s. (0.3202) | 0.0431n.s. | Rejected |

n.s. Not significant.

Our main research objective is to analyze the possibility of turning initially dissatisfied customers into evangelists of the firm, or prescribers—i.e. consumers who are willing to speak well of the company and to make positive recommendations to people in their circle of influence. To this end, the study proposes a conceptual model—rooted in proven theories—which has been empirically tested in the context of mobile telecommunications. The results allow us to offer a number of theoretical contributions and recommendations for business practice which are discussed in the following section.

First, it has been demonstrated that if customers perceive that the company strives to solve the problem occurred and offers a fair, the level of satisfaction with the service recovery process will increase significantly. In turn, these two are not the same background level. Perceived effort in a significantly positive influence on the perceived justice of customers, so that the role of the employees of the organization will be essential that when consumers evaluate their treatment or management of the complaint made by the company.

We also demonstrate that satisfaction with the service recovery process is a critical variable in the field of relationship marketing that will determine the degree of loyalty, commitment, and word-of-mouth. Therefore, this study contributes to this line of research highlighting the important role post-service recovery customer satisfaction plays in creating long-term customer-company relationships. Specifically, once there has been an unsatisfactory situation (service failure), properly solve this problem leads customers to show, in return for the investment made by the company-a set of attitudes and behaviors that result in a greater fidelity, engagement and willingness to communicate a word-of-mouth positive. Thus demonstrate research proposals launched by Kumar et al. (2010) and represented the primary objective of this study.

Based on these behaviors, the positive relationship between satisfaction and word-of-mouth is a very outstanding result. This relationship was not confirmed in all investigations carried out so far (Anderson, 1998; Kim and Smith, 2007), but the results obtained in our study provide empirical evidence that allows us to understand the patterns of consumer behavior in today's mobile sector context. So, following effective management of the problem by the company, allowing customers to recover their satisfaction, the organization can convert initially dissatisfied customers into prescribers of the organization.

Moreover, besides the level of satisfaction, greater customer engagement they will also have a greater predisposition to spread favorable views of the company. However, the results do not support the hypothesis that links loyalty and word-of-mouth customers. This result may be because in the current mobile phone industry, which increasingly includes a greater number of complaints, consumer loyalty is spurious (Dick and Basu, 1994). Such loyalty is more behavioral than attitudinal, i.e. customers continue to operate with the company for various reasons-convenience, location, environment, etc.—but their attitude toward it is not positive so they do not feel the need to spread favorable opinions about the company. Another possible explanation for this result may be found in the need to include some mediator variable between these variables. Sweeney and Swait (2008) measured the relationship between loyalty and word-of-mouth customer including the indirect effect the credibility of the brand. In this case, results for the structural model are not significant.

Finally, the results obtained demonstrate the superiority of the proposed model compared to an alternative model that considers the direct effects between the background model (perceived effort and justice) and positive word-of-mouth. This result sheds light on the importance of satisfaction as a key mediating variable to get those positive comments from customers. In this sense, the mere fact that the company shows an interest and strives to resolve service-related problems and provide a fair solution, is not enough for customers. Customer satisfaction, therefore, should be the main objective for companies and to get it is the only option to retain and to attract new customers in the future.

The context in which this paper has been developed also may help to understand the results. The mobile telephone sector in Spain reports a growing number of complaints each year so we are dealing with a set of particularly sensitive, demanding consumers. Achieving loyalty, therefore, is no simple task. Even when customers are loyal (according to the scale used in this work that reflects the intentions to continue working with the company in the future), they are usually from the behavioral point of view, but not attitudinal. This is due to the existence of high switching costs in the sector (Polo and Sese, 2009), which often represent an insurmountable barrier to change companies. According to Dick and Basu (1994) there are four types of loyalty: true loyalty, latent loyalty, spurious loyalty and zero loyalty. In this work, customer loyalty could be considered spurious loyalty that has a high degree of intent to repurchase, but a low degree of positive attitude toward the company. So, not being a loyalty based on affective and attitudinal issues, does not result in a predisposition to speak favorably of the company (word-of-mouth positive). Word-of-mouth would take place otherwise, since this behavior is based on attitudinal rather than calculative factors (Verhoef et al., 2002).

7Conclusions and implications for managementThis paper contributes to the literature by helping to clarify the significance of the association between post-service recovery customer satisfaction and word-of-mouth. Unlike work by authors like Kim and Smith (2007) and Carpenter (2008)—who find no significant correlation between these variables—our results show that initially dissatisfied customers can become prescribers; as long as they are satisfied with service recovery in terms of perceived effort and perceived justice. In this sense, our study highlights the importance of perceived effort and justice as antecedents to post-service recovery customer satisfaction, and confirms that neither variable, by itself, is enough to have a direct impact on word-of-mouth.

In addition, this study shows the clear impact perceived effort has on perceived justice and customer satisfaction. This result allows us to deduce that customers will value that employees are involved in their problems, working every day to resolve their complaints and informing them of the exact state of the service recovery process. Considering the consequences of the model, the results obtained allow us to argue that customer loyalty and willingness—not only to engage but also to become a prescriber—increase in correlation with customer satisfaction. Hence, the basic premises of Relationship Marketing are met in contexts which are initially defined by dissatisfaction, as understood through the lens of Reciprocity Theory.

Organizations, therefore, should do everything in their power to avoid that customers spread negative opinions among their social circles as a result of poor service recovery management. The literature has coined cases where this goal is not reached with the term “double deviation” (Bitner et al., 1990; Johnston and Fearne, 1999; Casado-Díaz and Nicolau-González, 2009): the company has not only fallen short of meeting initial customer expectations, but has failed to provide a satisfactory solution to the problem as well. These cases lead to the deterioration of the customer-company relationship, the search for new alternatives and negative word-of-mouth.

To prevent this, it is essential that firms resolve service failures in ways which customers deem satisfactory. In this sense, becoming familiar with customer needs and preferences, in a personalized way—i.e. finding out what types of compensation customers prefer (economic compensation, discounts on future purchases, gifts, etc.)—and getting feedback regarding which of several potential solutions customers prefer are very effective strategies which can result in better business performance. Of the three dimensions of perceived justice, consumers place most importance on distributive justice—based on compensation—and procedural justice, or how the complaint is managed. Hence, customers will feel more indebted to firms which respond quickly, manage their complaint effectively, reimburse them with the exact amount of the bill in question, and repair or replace faulty products in a timely fashion; yet the same customers will appreciate when employees are nice, apologetic and know how to empathize with them.

The impact of perceived effort on perceived justice and satisfaction, then, is owing to the fact that customers value employee efforts to resolve their problems and keep them informed throughout the service recovery process. For these strategies to be successful, therefore, companies must invest in staff training, as employee attitude and professionalism will be essential to achieving customer satisfaction; firms must emphasize the importance of being patient, engaging with customers and addressing complaints effectively. All efforts will be rewarded a posteriori: as Reciprocity Theory establishes, once service recovery has been achieved, satisfied customers will become prescribers who will contribute toward generating positive attitudes toward the company which, in turn, will enhance brand image and reputation, and help to attract new customers. Firms can profit from the investment, therefore—both in transactional (repurchase) and non-transactional terms (referrals/recommendations)—because customers tend to respond with greater loyalty and a higher degree of engagement to service recovery efforts.

Despite being a clear contribution to the existing literature, our study presents a number of limitations. As we have limited our analysis to the mobile phone industry, for instance, extrapolating findings to other sectors should be done with care—and only after having analyzed potential structural similarities and differences between the two contexts. Similarly, one should be cautious when interpreting findings relating to the correlation between post-service recovery customer satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth; while our study confirms the significance of this relationship, this may not be the case with other papers perhaps due to the sector analyzed. Furthermore, the questionnaires collected from a selection of mobile phone customers reflect personal perceptions and opinions, so it is possible that there may be some bias in their response. Finally, the data refer to a specific point in time and do not provide information regarding the duration of the customer-company relationship nor the type of complaint made.

In future studies, it would be worthwhile to conduct a longitudinal analysis of the entire service recovery process—from the moment of service failure to the resolution of the problem. It would also be interesting to gather data for variables which can have an impact on customer loyalty—such as the duration of the relationship and type of service failure. In line with Verhoef (2003) and others who argue that demographic variables contribute significantly to customer-centered research and hold valuable lessons for business management, it would be relevant to consider customer profile variables—e.g. age, sex, income and level of education—as moderating the structural model. It would also be interesting to replicate the study in another sector, making a distinction between behavioral and attitudinal engagement; and to do the same with the loyalty variable. In such a context—and taking into account the existing literature—customer engagement, or attitudinal loyalty, could have a significant impact on word-of-mouth.

Financial support from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Spain (project ECO2011-23027) and support from the Aragon Regional Government, Generés (S09) and Fondo Social Europeo are gratefully acknowledged. The second author also acknowledge the Minister Grant FPU AP2010/4448.

| Variables/items | Total sample | |||

| Cross-loadings | Composite reliability | Ave | R2 | |

| Perceived effort (Karatepe, 2006) | ||||

| Staff worked hard to resolve the problem. | 0.8893 | 0.9313 | 0.8187 | 0 |

| Staff made every effort to resolve the problem. | 0.9044 | |||

| Staff was very involved in resolving the problem. | 0.9205 | |||

| Perceived justice (DeWitt et al., 2008) | ||||

| DISJ1: After filing a complaint, the outcome was fair.DISJ2: The company provided me with what I needed. | 0.5391** | NA* | NA* | 0.4089 |

| PROJ1: The company responded promptly and justly to my needs.PROJ2: The company was flexible when dealing with my problem.PROJ3: Company policies & procedures were appropriate for dealing with my concerns. | 0.3622** | |||

| INTJ1: The company was sufficiently concerned about my problem.INTJ2: The company communicated with me appropriately. | 0.2651** | |||

| Post-recovery satisfaction (Karatepe, 2006) | ||||

| I am more satisfied with my mobile phone company since they solved my problem. | 0.942 | 0.9448 | 0.8954 | 0.6949 |

| My impression of my mobile phone company has improved since they solved my problem. | 0.9505 | |||

| Loyalty (Karatepe, 2006; DeWitt et al., 2008) | ||||

| This company is my first choice for this type of service. | 0.8743 | 0.8554 | 0.7415 | 0.4057 |

| I plan to stay on as a customer of this company in the future. | 0.8287 | |||

| Engagement (Cater and Cater, 2010) | ||||

| I like to feel associated with my mobile service provider. | 0.8246 | 0.8431 | 0.8232 | 0.4143 |

| My company and I are committed to maintaining a mutually satisfying relationship. | 0.882 | |||

| Word-of-mouth (De Matos et al., 2009) | ||||

| I will speak positively about the company to others. | 0.9425 | 0.7908 | 0.6778 | 0.8495 |

| I will encourage my friends to use this company's services. | 0.6208 | |||

| I will recommend this company to people who ask me for information. | 0.6802 | |||

NA (not available): as perceived justice indicators are considered to be formative the AVE cannot be calculated, as it only takes values for reflective constructs (Fornell and Lacker, 1981).

| Variables | Perceived effort | Perceived justice | Satisfaction | Commitment | Loyalty | Word-of-mouth |

| Perceived effort | 0.9048 | |||||

| Perceived justice | 0.6395 | NA** | ||||

| Satisfaction | 0.6731 | 0.8085 | 0.9462 | |||

| Commitment | 0.5859 | 0.7372 | 0.6437 | 0.9073 | ||

| Loyalty | 0.4201 | 0.5797 | 0.6212 | 0.5075 | 0.8611 | |

| Word-of-mouth | 0.6311 | 0.6283 | 0.718 | 0.5303 | 0.5774 | 0.823 |

*The data forming the diagonal line in bold corresponds to the square roots of the AVE (Average Variance Extracted) for the variables; the rest of the numbers represent correlations between constructs. All correlations are significant for p<0.01 (Fornell and Lacker, 1981).

NA, not available: as perceived justice indicators are considered to be formative the AVE cannot be calculated, as it only takes values for reflective constructs (Fornell and Lacker, 1981).

The authors acknowledge funding from the CICYT project ECO2011-23027, Project 276-03 (GENERÉS, S09), Department of Science, Technology and University of the Government of Aragon and the European Social Fund.

By non-transactional behaviors we mean a readiness to spread favorable views of the company and its products (positive word-of-mouth), participate in collaborative product design and development, share comments and opinions on websites and social networks, and maintain an ongoing dialog with the company through different commercial channels (Kumar et al., 2010; van Doorn et al., 2010).

We focus on positive word-of-mouth in this study—that is, that which spreads favorable information about the company and its products and serves to recommend them within a social network. We make a distinction, therefore, between positive and negative world-of-mouth (Holloway et al., 2005; Blodgett, 1994); the latter being driven by a desire to spread unfavorable information and opinions with a view to tarnish the company image and damage the firm commercially.

This sector was chosen due to the considerable increase in number of complaints registered each year (Instituto Nacional de Consumo, 2011); another factor driving this choice is the fact that the mobile sector has experienced a stable growth rate of 5.5% in the last year—over 58 million lines with a penetration of 118.5 lines per 100 inhabitants, according to the CMT report for 2011. This degree of saturation, coupled with a wide range of carrier options, has prompted companies to compete for market position via aggressive marketing and retention campaigns and strategies (Maicas and Sese, 2008; Polo and Sese, 2009)—explaining the inherent interest in delving deeper in this area.