Sleep disturbances, including disrupted sleep and short sleep duration, are highly prevalent and are prospectively associated with an increased risk for various chronic diseases, including cardiometabolic, neurodegenerative, and autoimmune diseases.

Material and methodsThis is a narrative review of the literature based on numerous articles published in peer-reviewed journals since the beginning of this century.

ResultsThe relationship between sleep disorders and metabolic dysregulation has been clearly established, mainly in the setting of modern epidemic of cardiometabolic disease, a cluster of conditions include obesity, insulin resistance, arterial hypertension, and dyslipidaemia, all of them considered as main risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD) and its clinical expression such as ischemic ictus, myocardial infarction and type 2 diabetes. Clinically viable tools to measure sleep duration and quality are needed for routine screening and intervention.

ConclusionsIn view of what has been exposed in this review, it is evident that the timing, amount, and quality of sleep are critical to reduce the burden of risk factors for several chronic disease, including ACVD and type 2 diabetes, and most relevant in young people. Future research studies should elucidate the effectiveness of multimodal interventions to counteract the risk of short sleep for optimal patient outcomes across the healthcare continuum, especially in young people.

Los trastornos del sueño, incluyendo el sueño interrumpido y el de corta duración son altamente prevalentes y están, prospectivamente, asociados con un incremento en el riesgo de varias enfermedades crónicas, incluyendo cardiometabólicas, neurodegenerativas y autoinmunes.

Material y métodosEsta es una revisión narrativa de la literatura basada en numerosos artículos publicados en revistas sometidas a un proceso de revisión por pares desde el comienzo de este siglo.

ResultadosLa relación entre los trastornos del sueño y la desregulación metabólica ha sido claramente establecida, fundamentalmente en el contexto de la epidemia moderna de la enfermedad cardiometabólica, una constelación de condiciones que incluyen obesidad, resistencia a la insulina, hipertensión arterial y dislipidemia, todas ellas consideradas como factores mayores de riesgo para enfermedad cardiovascular aterosclerótica (ECVA) y sus expresiones clínicas como el ictus isquémico, el infarto de miocardio y la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2). Se requiere de instrumentos clínicamente viables para medir la duración y la calidad del sueño durante estudios de rutina y de intervención.

ConclusionesEl momento, la cantidad y la duración del sueño son críticos en reducir la carga de los factores de riesgo para varias enfermedades crónicas, incluyendo la ECVA y la DM2, siendo de mayor relevancia en las personas jóvenes. Investigaciones futuras deben esclarecer la efectividad de las intervenciones multimodales para contrarrestar el riesgo del sueño corto para un mejor estilo vida a lo largo del continuo del cuidado de la salud, especialmente en la población joven.

Though rarely addressed, sleep is a crucial process for human beings, as is that of nourishment and reproduction, meticulously orchestrated by the brain, characterised by a dominance of the parasympathetic or vagal nervous system, which affords the cardiovascular and respiratory axes a chance to restore their equilibrium in response to stress or fatigue that occurs during waking hours. It is worth noting that sleep is the biological function that is the least known and most neglected in the context of general health.

It is worth clarifying that, while “sueño” (“dream”) is used as a synonym for “dormer” (“sleep”) in many publications in Spanish, there is a vast difference between the two. The term “dormer” refers to the behavioural act that causes us to lose consciousness and disconnect from environmental stimuli. The term “dormer”, on the other hand, refers to oneiric images, to the subjective process that is related to the mental activity of dreams.1 The connotation of the word “sueño” is clearer in English than in Spanish, such that “sleep” and “dream” are not used interchangeably as they are in Spanish, where the word “sueño” implies the oneiric activity of dreaming as well as the desire and behavior of sleeping. In this review, we will use “sueño” and “dormer” interchangeably.

Since the fifties of the last century, several researchers have devoted themselves to studying the neurobiology of sleeping and dreaming in humans and animals. Sleep has been characterised by several stages ranging from light sleep to deep sleep and dream sleep. During periods of sleep (without dreaming), four stages (I–IV) have been described according to brain electrical activity, which is typically slow–wave, and the behaviour that accompanies them. Conversely, when we sleep and dream, rapid eye movements (REM) take place, as if we were contemplating a landscape, and the electrical activity of the brain is characterised by high frequency, low voltage waves (beta waves, similar to those of wakefulness).2 For these reasons, neurophysiologists refer to the periods in which we dream as REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep.

Like nutrition, sleep health is recognised as a multidimensional construct given its complexity and impact on cardiometabolic and general health. Therefore, the study of sleep cannot focus on a single dimension as this will lead to incomplete conclusions about the role sleep plays in preserving health.

Over the course of our history, the natural cycle of sleep and wakefulness has been impacted by a number of changes due to progress, but there is no doubt that the factor that has definitively broken with the natural synchrony of our biological rhythms has been the introduction of artificial light. This has gradually conditioned and regulated all human activities, eventually imposing unnatural rhythms, justified in the world of work and its productive activities. Human beings have had to adapt to these new schedules, with the implementation of different work shifts, academic and leisure activities that modify natural processes, while simultaneously influencing quality of life with respect to health and often forgetting that the light/dark cycle is the primary means of synchronising the circadian rhythm, which is a critical factor because the body does not distinguish between sunlight and artificial light.3

Humans have a limited energy reserve, and the body is genetically programmed to rest in proportion to waking activities. It has been estimated that 33%–40% of our day should be devoted to sleep as a means by which to replenish the body’s energy stores.4

It has now become recognised more and more that disruption of the circadian rhythm can be a pervasive phenomenon that is not restricted to specific environments (e.g., in shift workers) and can accumulate over time, notably in bearing in mind the increase in daily exposures to factors that can disrupt circadian rhythms (for instance, exposure to light at night, the use of multimedia devices in the bedroom, etc.), although the impact of such ubiquitous exposures to chronic circadian disruption on cardiometabolic health has yet to be addressed at the population level.

It has been known for some decades that there is a pathophysiological link between sleep disturbances and cardiometabolic conditions, which is the subject of this narrative review.

Sleep, a little-known and disrespected biological functionRestful sleep is a fundamental part of good health and has been increasingly recognised by both doctors and the general public [as key] for physical and mental health; however, oddly, the lifestyle system encourages less sleep, owing to the numerous distractions (TV, telephone, WhatsApp®, Facebook®, etc.) that hinder greater consideration of this cardinal restorative function.5

By nature, all mammals experience a certain amount of neurological damage with wakefulness and the resulting residue, including remnants of damaged genes and proteins within the neuron, can regroup and cause neurological disease. Sleep contributes to the repair of such damage and the sweeping away of debris, briefly reducing, organising, and clearing away the residues that can lead to brain impairment.6

Sleep disturbances, such as insufficient sleep, insomnia, restless legs syndrome, irregularities or variation in sleep duration, fragmented sleep, and obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) occur in up to one third of adults, affecting many aspects of health, including carbohydrate metabolism, cardiac and respiratory function, and sexual function, among others.

Sleep is a part of human biology and is regarded as a requirement for life. It has been defined as “a naturally recurring and reversible state of perceptual disconnection, decreased awareness, and relative immobility,”7 and numerous epidemiological studies have identified poor or fragmented sleep to be a risk for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease.8

Although much of the existing information deals more with the negative consequences of sleep deprivation, it must be underscored that sleep health is a multidimensional construct with overlapping components such as duration, timing, regularity, efficiency, satisfaction, and impact on wakefulness, to which little attention is paid.9

The recommended number of hours of sleep varies as a function of age10–12:

- -

Newborns: 18 h

- -

Infants: between 10 and 12 h

- -

School-aged children: between 9 and 11 h

- -

Adolescents: between 8 and 10 h

- -

Young adults (18–64 years): between 7 and 9 h

- -

Seniors (≥65 years): between 7 and 8 h

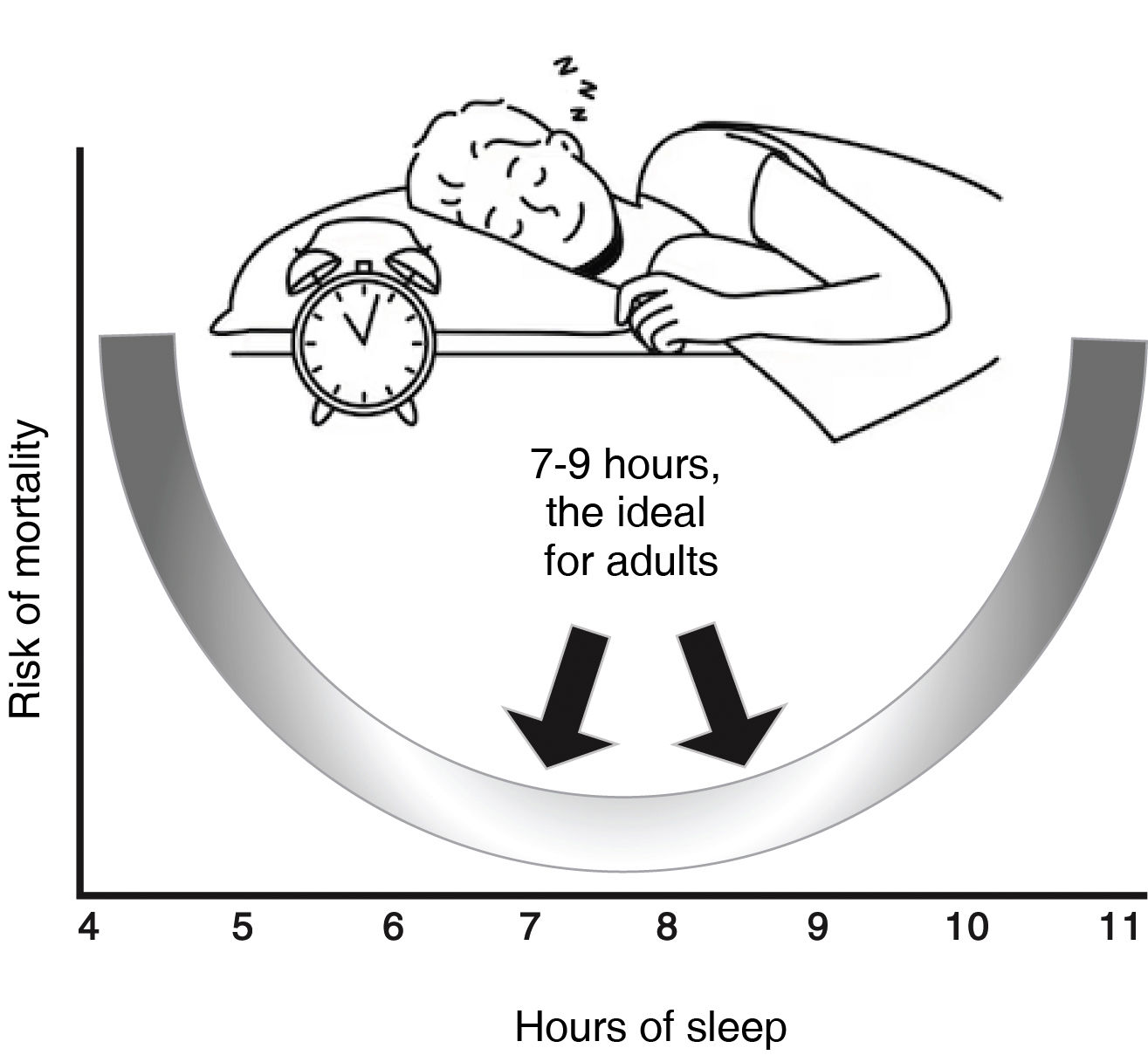

Nowadays, irregular sleep schedules, characterised by high day-to-day variability in the timing, duration, or schedule of sleep, are considered to represent a milder, albeit chronic, disruption of the circadian clock that is highly relevant across the entire population (Fig. 1).

U-curve on sleep duration and mortality. While there is no magic “number of hours of sleep” that works for all people of the same age, it is well known that most adults need between 7 and 9 h of sleep per night; however, after the age of 65 this amount decreases with less continuity of sleep (fragmented sleep). Irregular sleep schedules, characterised by high daily variability, duration, or timing of sleep, can constitute a milder, yet chronic, disruption of the circadian clock that is widely prevalent among the population.

Specifically, individuals who frequently alter how long or when they sleep from night to night may be at increased cardiometabolic risk due to disturbed circadian functions. Analysis of sleep regularity requires an assessment of the timing and duration of sleep over several nights and is often quantified using actigraphy over several days, although reliable information on individual variation can be obtained with most smartwatches; however, this method has yet to be validated.

Circadian rhythm, wakefulness, and sleepThe circadian rhythm is the brainchild of our biological clock that sets the pace for certain functions, the best example being sleep. During this stage, the body takes a well-deserved rest and allows the cardiovascular, central nervous, renal, and other systems to “recoup”. Consequently, blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) decrease.

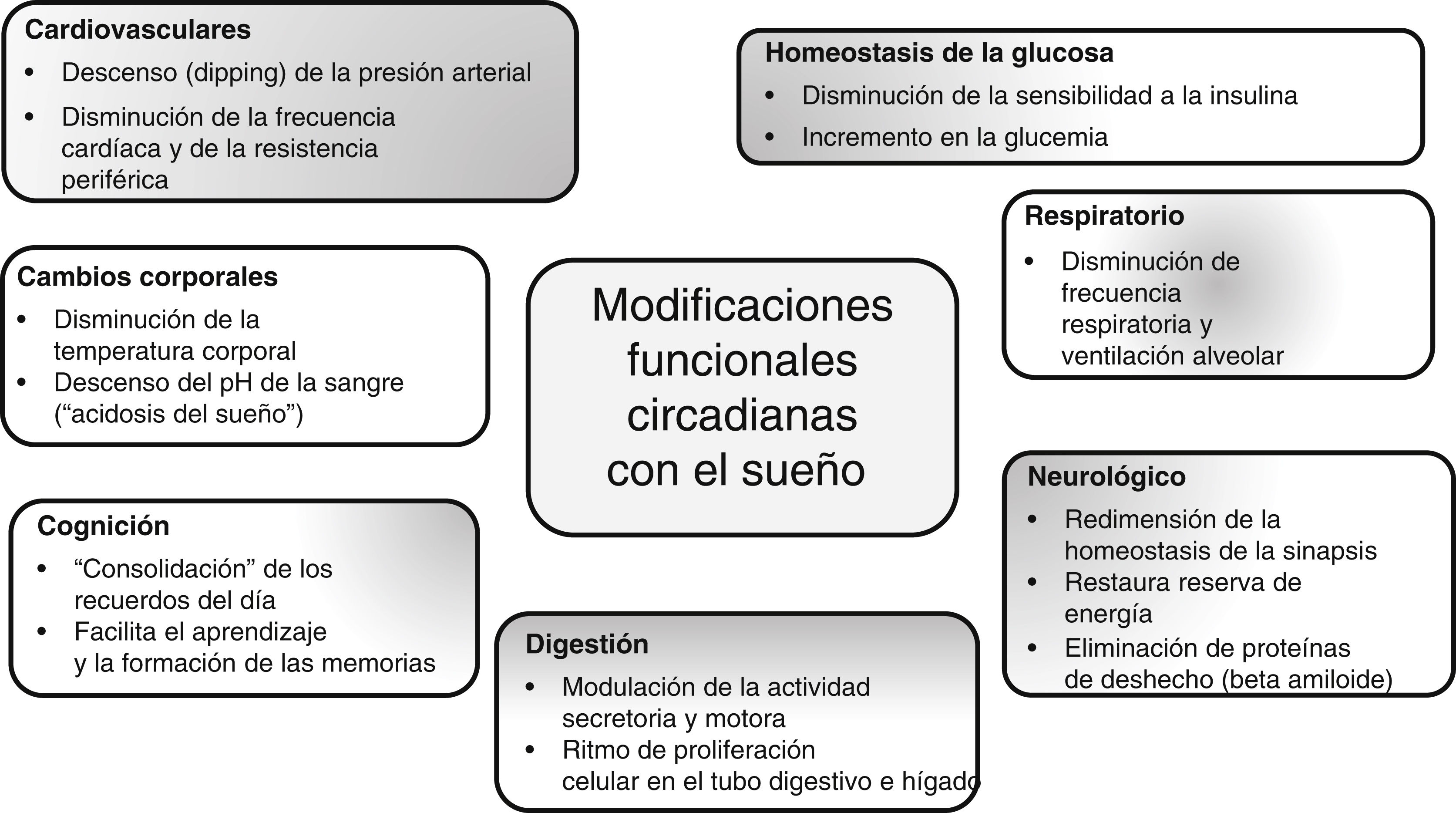

During sleep, governed by our circadian rhythm at night, a number of functional changes typically take place, some of which are outlined in Fig. 2.13–17

Circadian rhythm and modulation of bodily functions.13–17 The biological clock determines compliance with circadian rhythms in mammals and is closely linked to the functioning of numerous body systems, where nutrition, eating, and metabolic responses to food intake are especially regulated by circadian rhythms as well as diurnal variations throughout the day.

The rotation of the Earth on its axis exposes the planet’s inhabitants to daily cycles of light and dark. To adjust their activity to the periods of light, determined by the rising and setting of the sun, organisms have developed molecular clocks, called biological clocks, which operate in 24-h cycles and define the circadian rhythm (from the Latin circa or near and day). These internal timers respond to light penetrating tissues and cells, where highly complex molecular systems respond to the stimulus.18

The master clock is located in the brain, coordinates all the biological clocks of a living being by keeping them synchronised, and is located in the hypothalamus which receives direct input from the eyes to be processed, and define [sic] the various rhythms that modulate our physiology and general routine.19

It has now been well established that inherent circadian rhythms are a universal mechanism in a variety of biological processes, including metabolism. A clear circadian pattern is present from downstream gene expression to circulating metabolites, as well as in the secretion of hormones involved in regulating metabolism.20

Under normal conditions, sleep regulatory centres receive the signal for activation at dusk, causing us to feel sleepy at that time, and are gradually switched off in the morning. However, the biological clock can be altered for a variety of reasons, including9,13,14: genetic factors, hormones, drugs, behavioural alterations, neurological conditions, age, diet, or physical activity.

In short, our biological clock regulates the body’s physiology by means of hormones (such as cortisol and melatonin, the former with its highest concentration in the morning and then decreasing by the time we go to sleep, while the levels of the latter are always elevated at night because it is the hormone of darkness) and by the autonomic nervous system.

Feasible pathophysiological mechanisms during disturbed sleepOne substantial difficulty in assessing the cardiometabolic effects of short-duration sleep is the tremendous heterogeneity of experimental protocols, which can sometimes lead to controversial results. On the other hand, demographic studies are limited by individual and interindividual confounding factors, such as ethnicity, gender, genetics, environment, and social conditions. Furthermore, in demographic studies, the duration and quality of sleep are often patient-reported and not evaluated objectively with devices such as actigraphy or polysomnography. The use of both is probably the best approach inasmuch as they measure different and complementary dimensions of sleep, however, such techniques are not fully amenable for use in sufficiently large samples. This is an important reason why meta-analyses are so valid.

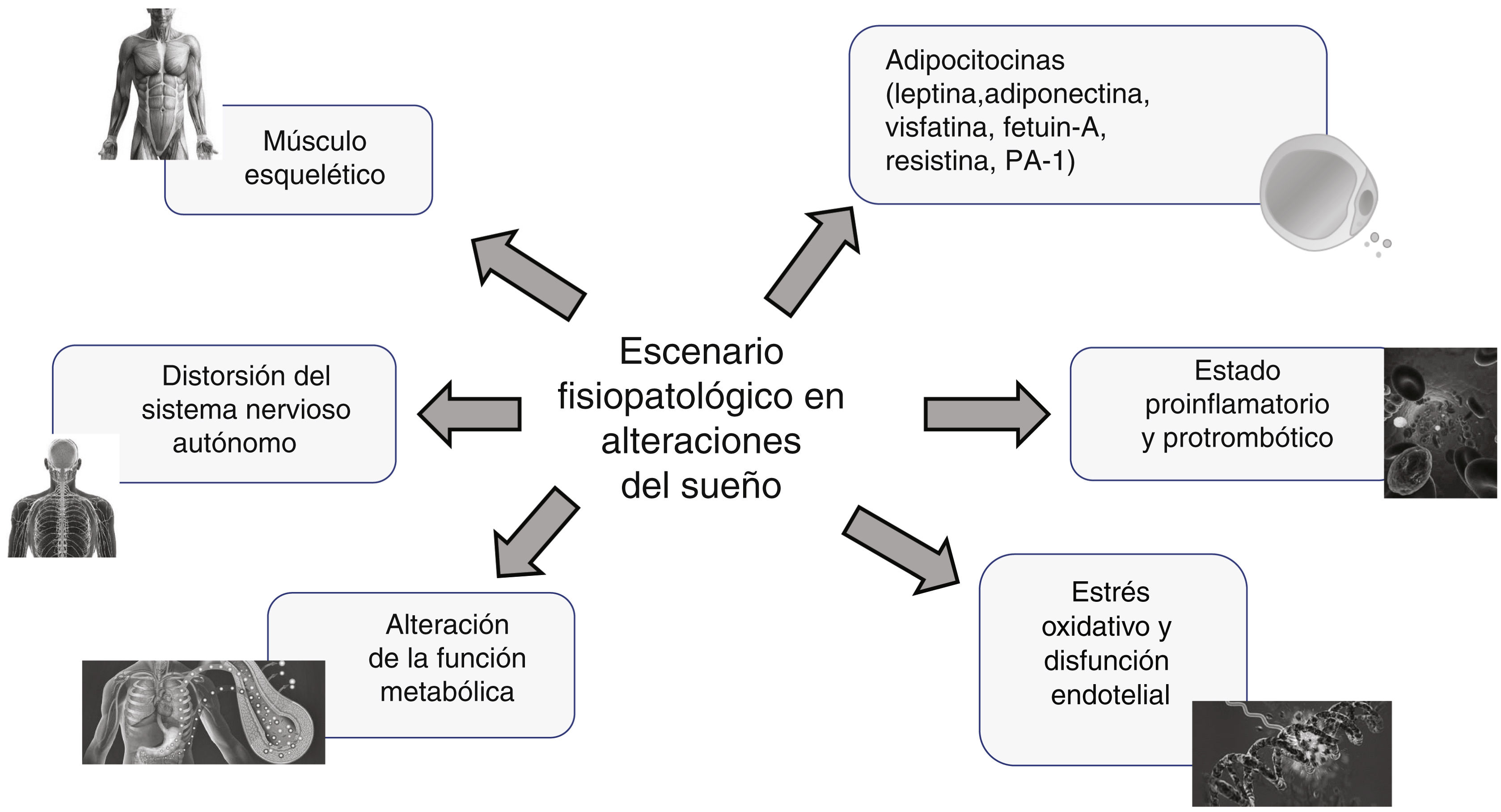

Given that sleep is one of the greatest enigmas among the biological functions of living beings and that the consequences of short sleep are well known, the mechanism of such an impact on health is fraught with numerous conjectures and speculations. Nevertheless, numerous experimental and observational studies point to a number of different actors at play as a multifactorial intervention (Fig. 3):

- a.

Distortion of the autonomic nervous system. Short-duration sleep is invariably associated with a major shift in the vagal sympathetic balance towards the preponderance of adrenergic tone resulting in the stimulation of several mechanisms that lead to increased cardiovascular risk such as arrhythmias, nocturnal BP and HR elevation, and atherosclerosis thanks to endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress, as well as through stimulation of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS).21 Experimental studies generally involve short-term exposure to sleep deprivation, but chronic exposure to sleep deprivation in the real-world context is, not surprisingly, conducive to ongoing sympathetic hyperactivity, with the full spectrum of cardiometabolic response that this entails. Experimental studies on the chronic effects of sleep deprivation in healthy subjects have yielded analogous results.22,23 The autonomic profile undergoes a change with decreasing variability of BP and HR with a shift in the vagal sympathetic balance towards almost absolute sympathetic dominance after five days of partial sleep deprivation with a consequent increase in plasma norepinephrine concentrations.22 Similar findings have been reported in a cohort of 30 healthy high school students.23

- b.

Proinflammatory and prothrombotic state. It is well known and acknowledged that inflammation is one of the most important intermediate mechanisms involved in the development of cardiovascular disease, and is a complex process involving the overexpression of several adhesion molecules, chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors, which promote the development of atherosclerosis.24 In a study that examined the effect of acute total sleep deprivation in the real-world setting by assaying several inflammatory biomarkers in the plasma of medical residents after a night on call, they found increased gamma interferon (IFNγ) with no changes in interleukins [IL], IL-2, IL-10, and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα); however, these results were not consistent. Meanwhile, IL-6 appears to have a circadian pattern and to correlate negatively with the amount of sleep the previous night.25 Acute sleep deprivation affects the circadian pattern of IL-6 secretion and results in hypersecretion during the day and hyposecretion at night.

- c.

Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are key to several vascular cellular functions including, growth, proliferation and migration of endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, angiogenesis, apoptosis, vascular tone, and host defence. Nevertheless, when their concentration is excessive, they can trigger vascular disease through direct and irreversible oxidative damage.26 Short-term experimental deprivation has proven to be associated with an increase in the concentration of myeloperoxidase, an enzyme that participates in the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (c-LDL) particles, which are especially atherogenic in this form.27,28 Increased concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) is involved in the release of oxidative radicals from activated neutrophils, which may account for the spike in myeloperoxidase concentrations.27,28

Pathophysiological overview of sleep disorders. A number of recent publications have defined the landscape of sleep quality and its links to multiple cardiometabolic disorders, including cardiovascular health, attributable to a combination of participating factors, which may be involved to a greater or lesser extent. PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

Increased endothelin-1 values were reported in adults with sleep of short duration and similarly, decreased endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent vascular reactivity after acute total sleep deprivation, associated with increased levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1, which is a marker of endothelial activation, and IL-6, which inhibits endothelium-dependent relaxation involving nitric oxide.29

- d.

Disturbance of metabolic function. Sleep and circadian rhythms are of crucial importance to the regulation of certain metabolic and endocrine functions. Studies in mice and rats have proven a strong connection between sleep deprivation and obesity by means of dysregulation of several weight control pathways, such as insulin secretion, leptin/ghrelin balance, and energy expenditure.30 Moreover, sleep deprivation can decrease sensitivity to endogenous stimuli that increase energy expenditure and, thereby, cause weight gain.31 In addition, inflammation acts as an intermediary that leads to a variety of metabolic changes. Adiponectin, a well-known anti-inflammatory hormone secreted by adipose tissue and involved in insulin sensitivity and lipid oxidation, has been studied in relation to sleep duration; however, adiponectin concentrations following sleep deprivation are inconsistent.32 Studies in humans confirmed data from animal studies: after partial sleep deprivation, increased blood glucose in response to both the intravenous glucose tolerance test and breakfast and decreased insulin responsiveness were demonstrated33 with elements that pointed to sympathetic hyperactivity as the mechanism underlying insulin resistance and decreased insulin release. Lipid changes with sleep deprivation is characterised by decreased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (c-LDL) in the acute phase after partial sleep deprivation (4 h per night for 5 nights), and by reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (c-HDL) following prolonged exposure to insufficient sleep reported by patients, suggesting that low c-LDL in the acute phase after sleep deprivation could be an adaptation to an inflammatory state.34 If the above metabolic changes persist, they could result in increased risk of obesity, hypercholesterolaemia, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), and thereby contribute to the increased risk of cardiovascular disease in those who are sleep deprived.

Similarly, increased free fatty acid concentrations have been described in sleep deprivation, which were associated with prolonged growth hormone secretion and high noradrenaline values, as well as decreased insulin sensitivity and increased insulin resistance.35

- e.

Skeletal muscle is another front-line player given its intimate ties to glucose and lipid homeostasis. In addition, it is the system that comprises the largest collection of peripheral clocks in the body; indeed, Zhang et al. estimated that some 1,600 circadian genes are expressed in skeletal muscle.36 Despite its dependence on light in the sleep/wake cycle, the peripheral clocks in skeletal muscle also rely on the regularity of the equilibrium between food and physical activity over 24 h to maintain homeostasis in the balance between energy intake and utilisation, a balance that is achieved by the muscle’s unique ability to adapt between demand (physical activity) and supply (food), which is why the skeletal muscle circadian clock plays such a critical role in glucose and lipid metabolism.36

- f.

Adipocytokines. By the end of the last century there was a surge of interest in research into the physiology and pathophysiology of adipose tissue, fuelled notably by the skyrocketing prevalence of obesity worldwide, in particular among younger age groups and its relationship with insulin resistance, an entity around which a number of cardiometabolic conditions associated with increased cardiovascular risk revolve.37

The discovery of leptin, the first known adipocytokine, was a milestone in the perception of adipose tissue as an endocrine organ,38 and since then, a number of substances secreted by adipose tissue have been identified and characterised for their cardiometabolic effects.

Leptin is produced largely by adipose tissue, however it is also synthesised in other organs, where its receptors are expressed. Among its different functions, it is involved in controlling energy homeostasis, neurogenesis, and neuroprotection, where central leptin resistance plays a prominent role in several neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Peripherally, leptin is a prime participant in regulating metabolism, bone mineral density, and muscle mass. All these actions can be influenced by changes in leptin concentrations, as well as in the mechanisms associated with resistance to it.39,40

Evidence suggests that adipocytokines also have a major role to play in mediating the association between sleep disturbance and cardiometabolic dysfunction; thus, for example, leptin has been proven to play a role in improving upper airway flow and hypopnoea during sleep and its deficiency is evidenced by significant changes in sleep structure and duration and in circadian rhythm, together with its metabolic roles in satiety, immune response, and insulin sensitivity.40–42 Other adipocytokines, such as adiponectin, are differential regulators in sleep disorders, and contribute to metabolic dysfunction. While leptin and adiponectin enhance insulin sensitivity, others, such as visfatin, fetuin-A, resistin, and plaminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), contribute to the development of glucose intolerance and also have proatherogenic properties, whereas, leptin and adiponectin, in contrast increase fatty acid oxidation, prevent foam cells from forming and improve lipid metabolism.43

It is worth noting that both obese and lipodystrophic patients have similar clinical stigmata: hypertriglyceridaemia, insulin resistance, and fatty liver. These disorders, in turn, lead to hypertension (HT), DM2, polycystic ovary syndrome, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, and cancers.

Obesity is not only a state of abnormally increased adipose tissue in the body, but also an increased release of biologically active adipocytokines. Because of their specific receptors located on the surface of target cells, these adipocytokines, released into the bloodstream, behave like classical hormones and affect the metabolism of tissues and organs. Furthermore, adipocytokines and cytokines can decrease the insulin sensitivity of tissues and trigger inflammation and the development of chronic complications. It can certainly be stated that, in an era of a worldwide pandemic of obesity, adipocytokines gain more and more importance as they are used in the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of various diseases (Fig. 3).43

In fact, obesity and sleep disorders are known to impact a number of adipcytokines that have more convergent functions on insulin sensitivity, energy expenditure, food intake, and tissue inflammation compared to other molecules and cellular processes. These findings highlight the important communication channels of these adipocytokines pointing toward a network effect between them and their areas of influence in systemic metabolic dysfunction.43,44

Cardiometabolic aspects of sleepSince the beginning of the first decade of this century, there has been an avalanche of publications defining sleep quality and how it is linked to various cardiometabolic disorders, including cardiovascular health, which is attributable in part to its influence on the risk of obesity due to alterations in energy intake and food choices.

A variety of research works have suggested that there is a relationship between diet, sleep, and the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).45 Increased energy intake during a period of sleep restriction can contribute to shifts in dietary intake and lead to increased frequency of eating, greater intake of total and saturated fats, in addition to snacks. In children and adolescents aged 9–17 years, later bedtimes have been associated with eating more junk food and skipping breakfast more often.46

These eating behaviours can contribute to weight gain and it is likely that such changes in dietary patterns caused by sleep restriction are an underlying mechanism for the relationship between sleep duration and CVD risk.47

The metabolic derangements triggered by circadian misalignment are more pronounced in people who are subject to night shift rotations or who experience «jet lag» or «social lag».48 In contrast, irregular sleep patterns are possibly the most common cause of circadian disruption in the general population, potentially leading to chronic and cumulative metabolic effects.3,7,14 In addition to biological rhythm alterations, sleep irregularity might also de-synchronise behavioural rhythms such as the timing of meals, which exacerbates the adverse metabolic consequences of irregular sleep.49 Consequently, mounting evidence has linked irregular sleep duration and timing, regardless of duration, to a higher prevalence of adverse changes in cardiometabolic factors such as overweight/obesity, dysglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, or HTN.50–52

In addition to the aforementioned, certain sleep pathologies, such as sleep apnoea and insomnia, also negatively affect overall health.

Sleep and the cardiovascular systemThe cardiovascular system exhibits robust circadian rhythms to maintain its normal functioning. Irregular sleep schedules, characterised by a great deal of daily variability in sleep duration or timing, represent a possibly milder, yet much more common and chronic disruption of circadian rhythms in the general population. Alterations in sleep metrics (variability, duration, regularity, and difficulty falling asleep) have been classically recognised as being associated with cardiovascular conditions, albeit most studies are observational.

In 1964, a study conducted by the American Cancer Society reported that subjects with seven hours of sleep had a lower mortality than those with more or less than 753 h of sleep. More recent studies and meta-analyses have reached similar conclusions8,27,54 and report a U-shaped relationship between [sleep] duration and mortality, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In addition, the duration of sleep has also been linked to multiple cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, DM2, and AHT.8,14,55

On the other hand, Daghlas et al.56 addressed the causal relationship between sleep duration and myocardial infarction using a genetic epidemiology approach with a Mendelian randomisation analysis which revealed that short sleepers, compared to 6–9 h/night sleepers, had a 20% higher risk of myocardial infarction.

Given the importance of sleep as a critical function, the American Heart Association (AHA) included sleep as one of the health-related variables that condition optimal cardiovascular and brain health as a primary measure of prevention57 and their new scoring algorithm, on a scale of 0–100 points, can be calculated online at www.heart.org/lifes,8 enabling a new cardiovascular health assessment scale (CHAS) to be generated that can be applied to anyone over the age of two years. The highest possible score is 100, categorising 0–50 as people with “low” cardiovascular health; 50–79 indicates a “moderate” degree of CV health, and greater than 80, “maximum” cardiovascular health.

Following these hypotheses and as part of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) programme, Makarem et al.58 studied the inclusion of sleep as a separate CVH metric along with other variables so as to derive a better approximation of health status and events during follow-up of participants who had complete data on sleep characteristics either by polysomnography, 7-day actigraphy, validated questionnaires, and outcomes. The results demonstrated that those with a healthy sleep status had lower BP, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and fasting blood glucose, as well as a 32%–42% lower prevalence of CVD and DM2, respectively.58

Analysing data from a sample of the MESA study and their relationship with coronary calcium score as a reliable marker of subclinical atherosclerosis, participants with greater sleep irregularity were more likely to have greater coronary calcium density than those with greater sleep regularity.59 Nevertheless, a surprising finding was the high proportion of sleep variability of more than 90 min over the course of a week in almost one in three participants, which proves that sleep irregularity is a very common pattern in the general population and not restricted only to people who work at night.

It is valid to consider these publications as the first prospective investigations on sleep regularity, in which chronic circadian disruption and intermittent sleep deprivation are seen to be markers of CVD risk, inasmuch as participants with the most irregular sleep duration or irregular patterns exhibited a higher risk of developing CVD during follow-up compared to those participants who had the most regular sleep pattern.

Of the major cardiovascular risk factors, HTN is the one that has been most widely researched thanks to studies with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) that have provided insight into the behaviour of this variable, as well as HR and respiration during sleep and the negative prognostic implications of the absence of a nocturnal decrease or increase in BP. Specifically, short sleep may influence BP in the form of alterations in autonomic equilibrium, hormonal imbalance, increased adiposity, metabolic dysfunction, and disruption of circadian rhythms.21–24,45,55 Observational studies have indicated that both short and prolonged sleep are associated with increased risk of hypertension, reduced nocturnal dipping, and higher morning BP elevation, with the most compelling evidence for sleep deprivation.21–24,45,55 These consequences have also been reported in women and ethnic minorities.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus and sleep disordersDM2 correlates closely with sleep disorders and can lead to physical and mental problems with the resultant impairment of quality of life for these patients, giving rise to anxiety, stress, daytime fatigue, and increasing their already existing risk of CVD or other comorbidities,60 as summarised below:

- a.

The prevalence of sleep disorders in patients who live with DM2 varies between 42% and 76.8%.60–62

- b.

Patients living with DM2 can exhibit all kinds of sleep disorders, from difficulty to initiate and maintain sleep to problems with both the duration and quality of sleep.63

- c.

The relationship between these entities is complex, can present simultaneously with the diagnosis of diabetes and can be either the cause or consequence of these disorders.64

- d.

Sleep plays a major role in normal endocrine function and its duration, whether for short or long periods of time, can increase the risk of DM2.65,66

- e.

Sleep disorders impede proper glycaemic control.

The American Association of Diabetes67 in its supplement on standards of care for the patient with DM2 recommends that the following be contemplated:

- a.

Evaluating the characteristics of sleep among people living with DM2.

- b.

Detecting whether there are any sleep disorders, sleep disruptions due to symptoms of the disease or for management needs.

- c.

The concern (anxiety) the patient may present regarding these disturbances.

The results of current scientific studies evidence that we are facing a global public health problem that is most deeply rooted among children and young people, which requires immediate and coordinated action by all agents of influence (educational, community, political, etc.) in order to reverse this distressing trend.5,22,68 The rise of new screen technology, mobile phones in particular, has led to a change in many young people’s lifestyles, which often has a detrimental effect on their sleep cycle. Likewise, the fewer hours of physical education in schools and colleges in many parts of the world may also limit the ability of many young people to fulfil the physical activity guidelines,68 which is a situation that encourages sedentary lifestyles, changes in eating habits, and obesity.

The issue of sleep disorders and the risk of cardiometabolic conditions has been a focus of attention in recent years, although for decades, it was already known that children who slept less than necessary from the age of three were more likely to be overweight by the age of seven.69,70 The systematic review undertaken by Hermes et al.71 found that 13 of 24 published studies on the subject indicated that short sleep duration (<9–10 h) was associated with overweight in children, poor nutritional quality together with high intake of sweetened drinks and stimulants before bedtime, as well as micronutrient deficiency. The systematic review and meta-analysis by Miller et al.72 sought to determine whether short sleep duration correlated with the incidence of obesity and whether beneficial sleep interventions reduce weight gain in preschool children; it concluded that: a) the risk of developing overweight/obesity was greater in children who slept too little and b) interventional studies demonstrated that improved sleep may be favourably associated with reduced weight gain in these children.

Sleep and intellectual impairmentThe existence of a true brain lymphatic system has recently been proven; it is called the glymphatic system and consists of arterial and venous paravascular spaces and dural lymphatics, and is responsible for clearing the cerebral interstitial space. The protein aquaporin-4, located in the astrocyte feet opposite the paravascular spaces, plays a key role in eliminating waste molecules, such as beta-amyloid protein or tau.73 This glymphatic system is activated during sleep, especially during the slow–wave phase and if one sleeps on their side, with physical exercise and declines with ageing and is inhibited in the waking state, so much so that the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can be decreased by up to 95% and the clearance of protein Aβ can be delayed by up to half merely by being awake with the consequent accumulation of protein Aβ and acceleration in the formation of amyloid plaques.73,74

The glymphatic and meningeal lymphatic systems are critical for central nervous system homeostasis and their malfunctioning complicates the picture of neurodegenerative diseases. In addition, sleep deprivation is associated with the production of the protein Aβ and short sleep, as well as poor quality sleep, can lead to a burden of higher concentrations of this protein.75

ConclusionsIt must be underscored that, with the modernisation of society, the increase in nightlife, and the longer working hours, there is less time for sleep for people living in large cities, with a high percentage of their inhabitants over 15 years of age suffering from sleep disturbances, specifically difficulty in falling asleep, intermittent waking, or fragmented sleep, early awakening, and the inability to fall back to sleep and, perhaps the most common, variability in the time spent sleeping.

The societal trend of increasing sleep deprivation and circadian rhythm disturbance (CRD) in the population should alert health, public policy, and scientific bodies to the possible risk of an increased incidence in the future epidemic of Alzheimer’s disease.

Growing evidence is more and more consistent in demonstrating that maintaining a regular sleep schedule has beneficial cardiometabolic effects, which, coupled with other healthy lifestyle habits (diet, physical activity, non-smoking, etc.) can enhance current prevention strategies for a broad range of cardiometabolic diseases.

Furthermore, it has also been established that interventions that promote sleep hygiene and encourage regular sleep schedules are consistently linked to a healthier cardiometabolic profile, especially in the young population, including young adults.

Further studies are needed to identify behavioural strategies that can improve sleep habits in different population groups and to assess the effects of such interventions on cardiometabolic risk, both in the short and long term.

In light of the significance of the importance of good sleep or healthy sleep based on the findings of this review, it is essential that current scientific knowledge regarding the molecular mechanisms of sleep deprivation or sleep debt and circadian rhythm disturbances be integrated in order to define objectives and procedures in clinical practice to better clarify sleep disorders or poor sleep habits.

FundingThe authors state that they have not received any funding to draft this document.

Authors’ contributionsAll of the authors participated in the conception and design of the text, its drafting, and approval of the manuscript submitted.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that there are no competing economic or personal interests that may have influenced the elaboration of this document.