Managing moderate to severe psoriasis in older adults is complex due to factors characteristic of the later years of life, such as associated comorbidity, polypharmacy, and immunosenescence. This consensus statement discusses 17 recommendations for managing treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis in patients older than 65 years. The recommendations were proposed by a committee of 6 dermatologists who reviewed the literature. Fifty-one members of the Psoriasis Working Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) then applied the Delphi process in 2 rounds to reach consensus on which principles to adopt. The recommendations can help to improve management, outcomes, and prognosis for older adults with moderate to severe psoriasis.

El abordaje terapéutico de pacientes de edad avanzada con psoriasis en placas moderada-grave es complejo debido, entre otros factores, a las comorbilidades asociadas, a la polimedicación y a la inmunosenescencia propias de este grupo de edad. En el presente documento se recogen 17 recomendaciones para el manejo de la psoriasis moderada-grave en pacientes de edad avanzada (>65 años). Estas recomendaciones han sido propuestas por un comité científico de seis dermatólogos a partir de una revisión de la literatura científica y consensuadas entre 51 miembros del Grupo de Psoriasis de la Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología mediante dos rondas de consulta Delphi. En los pacientes con psoriasis moderada-grave de edad avanzada, estas recomendaciones pueden mejorar su manejo, los resultados y el pronóstico.

Due to the chronic nature of psoriasis and the increasing life expectancy of the population, older adults constitute a growing subgroup among patients with this disease.1 It is estimated that 13% of patients with psoriasis experience their first symptoms after 60 years of age, and that approximately 15% of this subgroup develop moderate to severe disease.2

However, since elderly patients are usually excluded from clinical trials, only limited evidence is available on the efficacy and safety of therapy in this subgroup.3 Furthermore, the management of psoriasis in this population is more complex owing to the increased risk of adverse effects (AE) in older patients and the greater prevalence of comorbidities, polypharmacy and immunosenescence.4 As a result, biologic therapies are prescribed more often in younger than in older patients1,2 and there may be an unjustified tendency to undertreat elderly patients.5

These circumstances have given rise to the need for a therapeutic approach that can afford the dermatologist greater confidence and security in the management of psoriasis in older patients. The aim of the present study was to develop evidence-based recommendations on the management of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in patients aged over 65 years.

Material and MethodsA Delphi exercise was carried out with members of the Psoriasis Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV). The questionnaire used in the first round was developed on the basis of a review of the literature and the advice of a scientific committee composed of 6 expert dermatologists (JM, JCRC, IB, LG, SMC, PC). The initial questionnaire comprised 34 statements. The members of the expert panel rated their degree of agreement on a 9-point Likert scale. Consensus was defined as at least 75% of the panelists expressing some degree of agreement (7–9) or disagreement (1–3). Statements on which the panel did not reach consensus in the first round were restated in the second round.

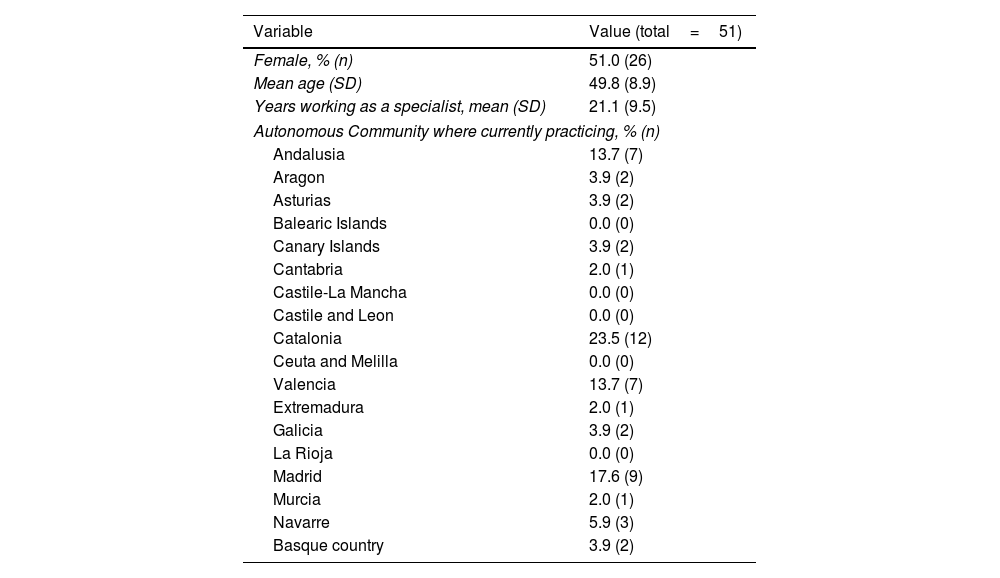

ResultsThe questionnaire was sent to all the members of the Psoriasis Group (n=151); a response was received from 51 members in the first round (33.8% response rate) and 38 of those (74.5%) in the second round (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and Professional Variables.

| Variable | Value (total=51) |

|---|---|

| Female, % (n) | 51.0 (26) |

| Mean age (SD) | 49.8 (8.9) |

| Years working as a specialist, mean (SD) | 21.1 (9.5) |

| Autonomous Community where currently practicing, % (n) | |

| Andalusia | 13.7 (7) |

| Aragon | 3.9 (2) |

| Asturias | 3.9 (2) |

| Balearic Islands | 0.0 (0) |

| Canary Islands | 3.9 (2) |

| Cantabria | 2.0 (1) |

| Castile-La Mancha | 0.0 (0) |

| Castile and Leon | 0.0 (0) |

| Catalonia | 23.5 (12) |

| Ceuta and Melilla | 0.0 (0) |

| Valencia | 13.7 (7) |

| Extremadura | 2.0 (1) |

| Galicia | 3.9 (2) |

| La Rioja | 0.0 (0) |

| Madrid | 17.6 (9) |

| Murcia | 2.0 (1) |

| Navarre | 5.9 (3) |

| Basque country | 3.9 (2) |

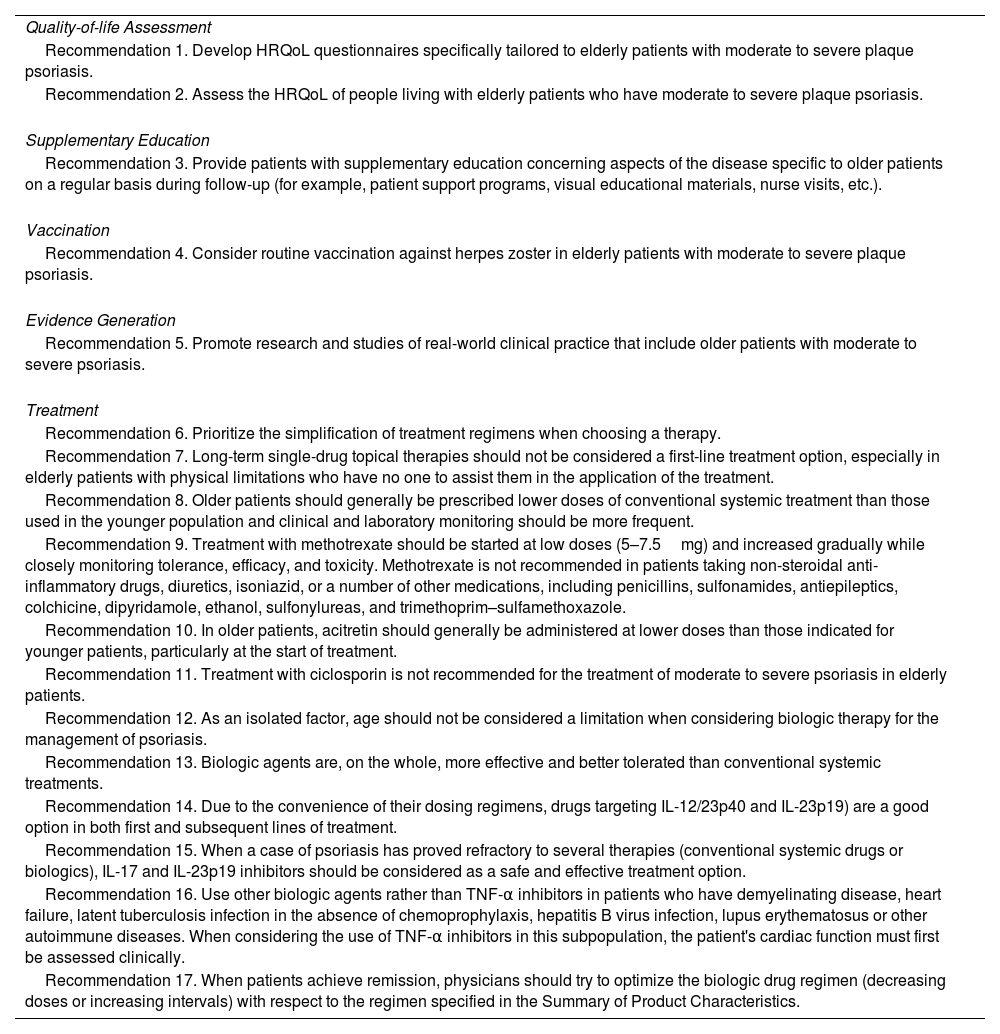

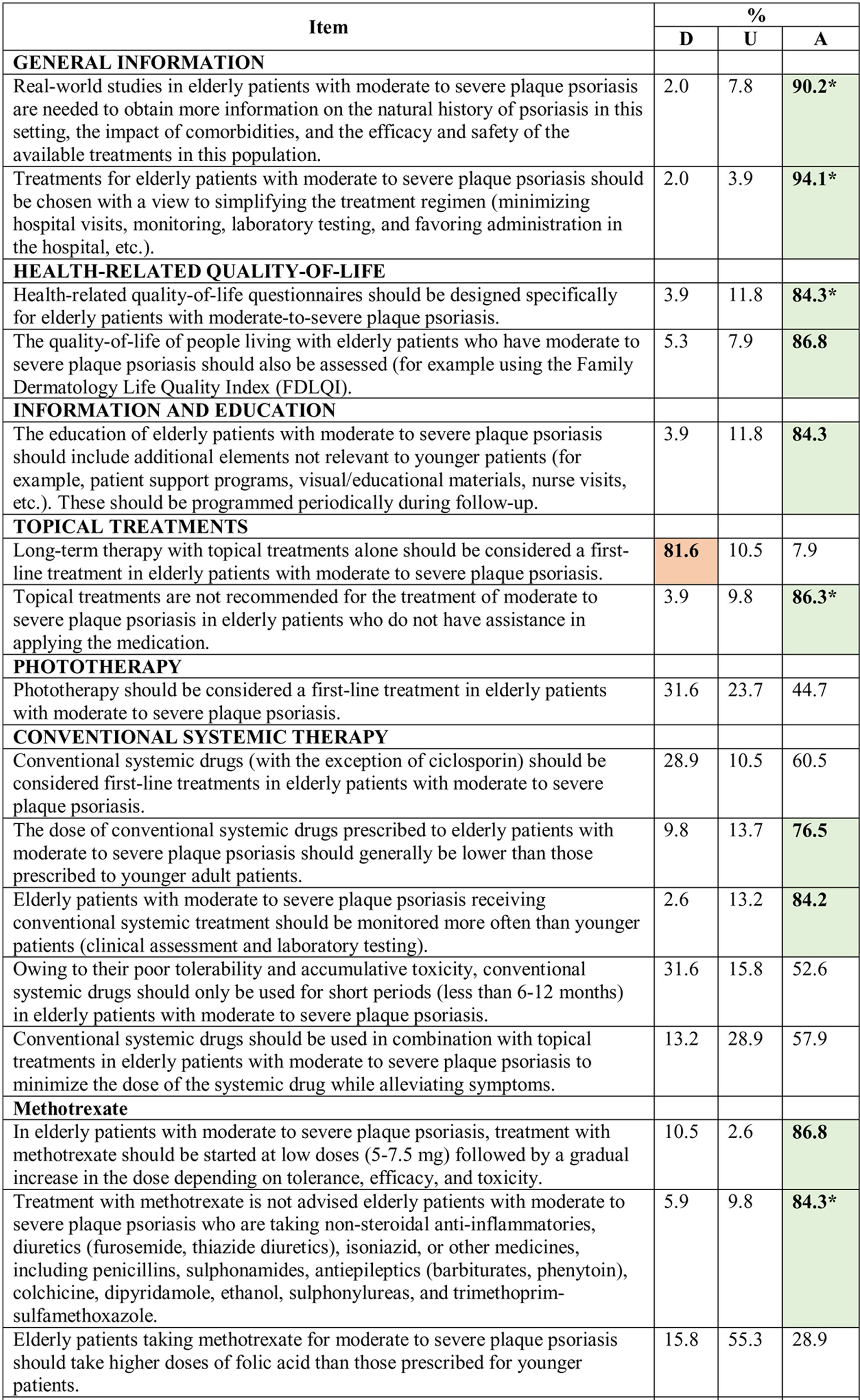

Consensus was achieved on 22 of the 34 statements (13 in the first and 9 in the second round) (Table 2). Based on these results, the scientific committee proposed 17 recommendations, grouped into 5 blocks according to topic (Table 3).

Results of the Delphi Method.

Abbreviations: A, agreement (7, moderately agree; 8, agree; 9, strongly agree); D, disagreement (1, strongly disagree; 2, disagree; 3, moderately agree); IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; U, undecided (4, mildly disagree; 5, neither agree nor disagree; 6, mildly agree).

*Agreement achieved in first round of the Delphi exercise.

Bold face indicates consensus (>75% of participants in agreement or disagreement).

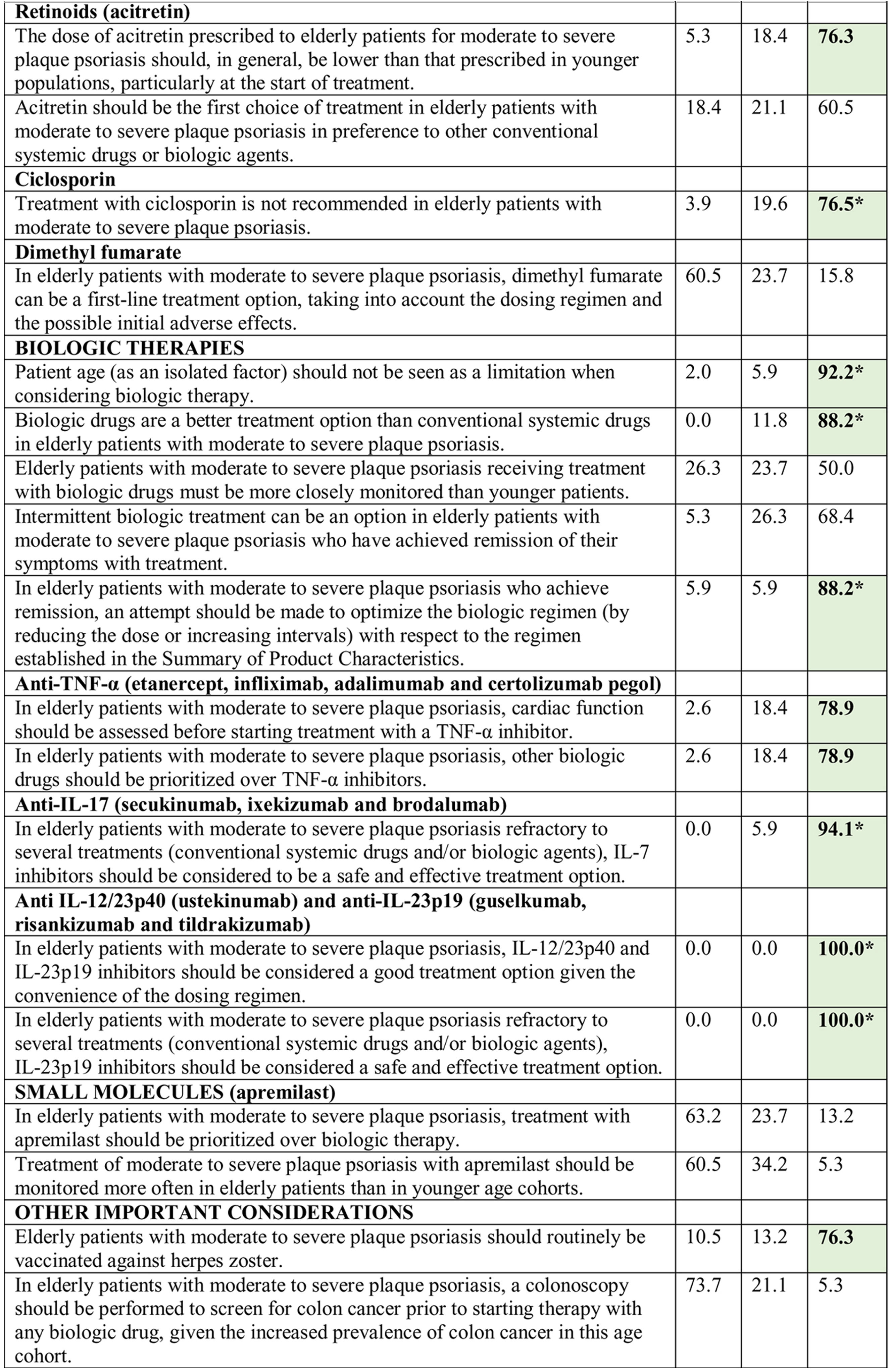

Recommendations Agreed by Consensus.

| Quality-of-life Assessment |

| Recommendation 1. Develop HRQoL questionnaires specifically tailored to elderly patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. |

| Recommendation 2. Assess the HRQoL of people living with elderly patients who have moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. |

| Supplementary Education |

| Recommendation 3. Provide patients with supplementary education concerning aspects of the disease specific to older patients on a regular basis during follow-up (for example, patient support programs, visual educational materials, nurse visits, etc.). |

| Vaccination |

| Recommendation 4. Consider routine vaccination against herpes zoster in elderly patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. |

| Evidence Generation |

| Recommendation 5. Promote research and studies of real-world clinical practice that include older patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. |

| Treatment |

| Recommendation 6. Prioritize the simplification of treatment regimens when choosing a therapy. |

| Recommendation 7. Long-term single-drug topical therapies should not be considered a first-line treatment option, especially in elderly patients with physical limitations who have no one to assist them in the application of the treatment. |

| Recommendation 8. Older patients should generally be prescribed lower doses of conventional systemic treatment than those used in the younger population and clinical and laboratory monitoring should be more frequent. |

| Recommendation 9. Treatment with methotrexate should be started at low doses (5–7.5mg) and increased gradually while closely monitoring tolerance, efficacy, and toxicity. Methotrexate is not recommended in patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, isoniazid, or a number of other medications, including penicillins, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, colchicine, dipyridamole, ethanol, sulfonylureas, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole. |

| Recommendation 10. In older patients, acitretin should generally be administered at lower doses than those indicated for younger patients, particularly at the start of treatment. |

| Recommendation 11. Treatment with ciclosporin is not recommended for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in elderly patients. |

| Recommendation 12. As an isolated factor, age should not be considered a limitation when considering biologic therapy for the management of psoriasis. |

| Recommendation 13. Biologic agents are, on the whole, more effective and better tolerated than conventional systemic treatments. |

| Recommendation 14. Due to the convenience of their dosing regimens, drugs targeting IL-12/23p40 and IL-23p19) are a good option in both first and subsequent lines of treatment. |

| Recommendation 15. When a case of psoriasis has proved refractory to several therapies (conventional systemic drugs or biologics), IL-17 and IL-23p19 inhibitors should be considered as a safe and effective treatment option. |

| Recommendation 16. Use other biologic agents rather than TNF-α inhibitors in patients who have demyelinating disease, heart failure, latent tuberculosis infection in the absence of chemoprophylaxis, hepatitis B virus infection, lupus erythematosus or other autoimmune diseases. When considering the use of TNF-α inhibitors in this subpopulation, the patient's cardiac function must first be assessed clinically. |

| Recommendation 17. When patients achieve remission, physicians should try to optimize the biologic drug regimen (decreasing doses or increasing intervals) with respect to the regimen specified in the Summary of Product Characteristics. |

Abbreviations: HRQoL, health-related quality-of-life; IL, interleukin; PUVA, psoralen UVA; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Recommendation 1. Develop health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) questionnaires specifically tailored to elderly patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Given that psoriasis affects the HRQoL of older patients physically, socially and emotionally,6 treatment should be directed toward improving all those areas.7,8 HRQoL should, therefore, be assessed during follow-up. While a number of different tools are currently used to assess HRQoL in these patients,9,10 the one most often used is the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).11 However, many older patients find it difficult to complete these questionnaires on their own due to vision problems or difficulty understanding the questions. This means that they have to depend on a family member or caregiver to complete the questionnaires, which can limit the usefulness and/or the validity of the tool. Furthermore, some of the items included (for example items relating to sexual activity, work or sports) may not be very relevant and can distort the results.

Recommendation 2. Assess the HRQoL of people living with elderly patients who have moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

The impact of psoriasis is not limited only to the patient but can also affect family members and people living with the patient, who may play an important role in their care.12 For this reason, the HRQoL of people living with the patient should also be assessed and the best tool for this purpose is the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI).12

Block 2: Supplementary EducationRecommendation 3. Provide patients with supplementary education concerning aspects of the disease specific to older age on a regular basis during follow-up.

The needs of older patients differ from those of younger adults owing to the specific characteristics of the aging process.13 It is, therefore, crucial to foster the development of targeted support programs and visual educational materials adapted to this subgroup.

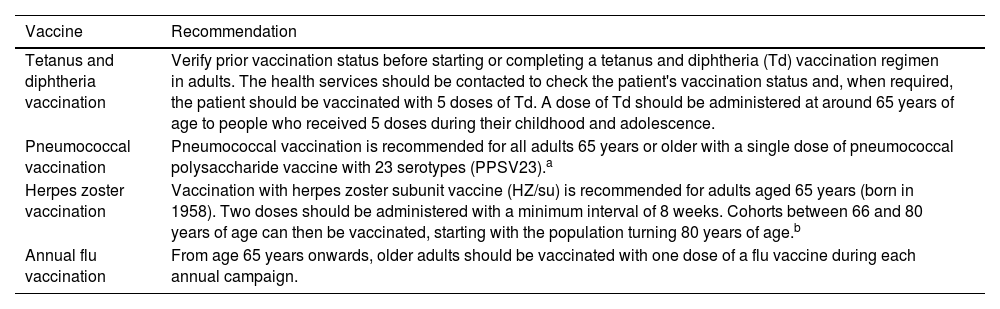

Block 3: VaccinationRecommendation 4. Consider routine vaccination against herpes zoster (HZ) in elderly patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

The Spanish Ministry of Health recommends vaccination with the new recombinant and adjuvanted HZ subunit vaccine (HZ/su) for people over 65 years of age, irrespective of underlying diseases or prescribed medication14,15 (Table 4) given that the prevalence of HZ infection increases with age.16 Moreover, autoimmune diseases, such as psoriasis,16 and certain systemic drugs, for example TNF-α inhibitors, are associated with a higher risk of reactivation.17–21

Recommended Routine Vaccination for Adults Aged≥65.

| Vaccine | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Tetanus and diphtheria vaccination | Verify prior vaccination status before starting or completing a tetanus and diphtheria (Td) vaccination regimen in adults. The health services should be contacted to check the patient's vaccination status and, when required, the patient should be vaccinated with 5 doses of Td. A dose of Td should be administered at around 65 years of age to people who received 5 doses during their childhood and adolescence. |

| Pneumococcal vaccination | Pneumococcal vaccination is recommended for all adults 65 years or older with a single dose of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine with 23 serotypes (PPSV23).a |

| Herpes zoster vaccination | Vaccination with herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) is recommended for adults aged 65 years (born in 1958). Two doses should be administered with a minimum interval of 8 weeks. Cohorts between 66 and 80 years of age can then be vaccinated, starting with the population turning 80 years of age.b |

| Annual flu vaccination | From age 65 years onwards, older adults should be vaccinated with one dose of a flu vaccine during each annual campaign. |

The new 20-serotype pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (VNC20) is now available and will gradually replace VPN23.

Rare cases of adults ≥50 years of age with no evidence of immunity to varicella should receive two doses of the vaccine. Clinical studies on the use of the varicella vaccine in adults over 65 years of age do not include a sufficient number of cases to determine whether the immune response achieved in this group is similar to that observed in younger people, although on the rare occasions when a person 50 years of age or older is seronegative for varicella, he or she should, in the absence of contraindications, receive two doses of the vaccine.

Recommendation 5. Promote research and studies of real-world clinical practice that include older patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

Since very little scientific evidence is currently available on the natural course of psoriasis and its associated comorbidities in elderly patients,22 studies are needed of real-world clinical practice that include this older cohort to generate evidence on the natural history of the disease in this subpopulation and on the effectiveness and safety of available treatments.

Block 5: TreatmentRecommendation 6. Prioritize the simplification of treatment regimens when choosing a therapy.

Elderly patients have specific therapeutic needs. Safety and the simplicity of administration should be prioritized when choosing treatment.23,24 Treatments with a better safety profile and simpler administration protocols are recommended for these patients.25

Recommendation 7. Long-term single-drug topical therapies should not be considered a first-line treatment option, especially in elderly patients with physical limitations who have no one to assist them in the application of the treatment.

Topical therapies are associated with fewer AEs and drug interactions than systemic drugs, a significant advantage in polymedicated patients.26 However, the risk of skin atrophy associated with the use of topical steroids is higher in the elderly population.7,26 Moreover, long-term adherence to topical therapy tends to be low27 and these treatments may be inappropriate if the patient has physical limitations and no one to assist them in the application of the treatment.26

Recommendation 8. Older patients should generally be prescribed lower doses of conventional systemic treatment than those used in the younger population and clinical and laboratory monitoring should be more frequent.

The use of conventional systemic treatment as a first-line therapy in elderly patients with psoriasis remains a subject of debate. Due to the poor tolerability and organ-specific cumulative toxicity27 of conventional systemic drugs and the risk in older adults of myelosuppression due to immunosenescence,7 special care should be taken with these drugs in older patients.11

Recommendation 9. Treatment with methotrexate should be started at low doses (5–7.5mg) and increased gradually while closely monitoring tolerance, efficacy, and toxicity. Methotrexate is not recommended in patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, isoniazid, or a number of other medications, including penicillins, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, colchicine, dipyridamole, ethanol, sulfonylureas, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole.

Advanced age is associated with a greater prevalence of comorbid diseases, such as dyslipidemia, diabetes, renal insufficiency, and obesity, all of which increase the risk of toxicity associated with methotrexate.21,28 Consequently, it has been suggested that treatment with methotrexate should be started at low doses, with gradual dose escalation if deemed necessary.11,26 The Summary of Product Characteristics states that treatment with methotrexate is not recommended if the patient is already receiving any of the drugs listed above.

Recommendation 10. In older patients, acitretin should generally be administered at lower doses than those indicated for younger adults, particularly at the start of treatment.

In elderly patients, acitretin is less effective than other drugs,21,29 but it is not an immunosuppressant and therefore it plays a unique role in the strategies used in the management of psoriasis.30 However, clinicans should bear in mind that older adults can be particularly affected by certain AE's, including the following: (1) dryness of the skin and mucosa, which may aggravate the xerosis characteristic of this age group30; (2) hypertriglyceridemia, which increases cardiovascular risk31; and (3) acitretin's contraindication for patients with renal or hepatic insufficiency,21 diseases that are more prevalent in older patients. While there are no differences in acitretin dosing regimens for older and younger patients, lower doses are more effective in older adults.21

Recommendation 11. Treatment with ciclosporin is not recommended for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in elderly patients.

The risk of renal toxicity, serious infections, and cancer increases with age.11,25 Older patients are also at increased risk for hypertension and other AEs associated with this drug.7,29 As the pharmacokinetics and/or pharmaco-dynamics of ciclosporin can be affected by certain drugs commonly prescribed to older patients, great caution must be exercised when prescribing ciclosporin in this cohort.21

Recommendation 12. As an isolated factor, age should not be considered a limitation when considering biologic therapy for the management of psoriasis.

No age-related variations in treatment efficacy have been observed in moderate to severe psoriasis.2,32 Despite this, in clinical practice, fewer biologic drugs are prescribed to elderly patients.2

Recommendation 13. Biologic agents are, on the whole, more effective and better tolerated than conventional systemic treatments.

Spanish Treatment Appraisal Reports33–38 have positioned biologic drugs as a second-line treatment for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis for use only when conventional systemic treatments and/or PUVA are contraindicated, not tolerated, or fail to achieve an acceptable response. However, biologic therapy is associated with greater efficacy, a lower probability of organ-specific toxicity, and greater convenience in terms of administration than conventional systemic agents.7,21,25,39

Few AEs associated with biologic therapies have been reported in the geriatric population.1,29,32,40–42 Owing to their greater safety and tolerability,21,27,39,40,44 biologic agents are a more appropriate long-term treatment than conventional systemic treatments in this population.43

In any event, elderly patients should always be closely monitored because of the increased risk of infection7 and because severe AEs tend to be more common in this cohort, irrespective of the type of treatment prescribed.2 However, biologic agents are a safe and effective option when appropriate prophylactic measures are taken.

Recommendation 14. Due to the convenience of their dosing regimens, drugs targeting interleukin (IL)-12/23p40 and IL-23p19 are a good option in both first and subsequent lines of treatment.

In patients of advanced age with moderate to severe psoriasis, IL-23 inhibitors are a safe and effective option32 which also improves HRQoL.21,2,43–48 Furthermore, it is likely that the risk of infection is lower with IL-12/23p40 and IL-23p19 inhibitors than with first generation biologic agents and conventional systemic drugs.7 They also have the added advantage of more convenient administration protocols.

Recommendation 15. When a case of psoriasis has proved refractory to several therapies (conventional systemic drugs or biologics), IL-17 and IL-23p19 inhibitors should be considered as a safe and effective treatment option.

IL-17 inhibitors have been shown to be safe and effective in elderly patients.25 The main AEs reported in older patients on these drugs do not seem to differ from those reported in younger cohorts despite the higher prevalence of comorbidities in the elderly population.45 Oral candidiasis is the only AE associated with the use of IL-17 inhibitors that could have a higher incidence in this subgroup.27

Recommendation 16. Use other biologic agents rather than TNF-α inhibitors in patients who have demyelinating disease, heart failure (HF), latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) in the absence of chemoprophylaxis, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, lupus erythematosus or other autoimmune diseases. When considering the use of TNF-α inhibitors in this subpopulation, the patient's cardiac function must first be assessed clinically.

Caution must be exercised when considering the prescription of TNF-α inhibitors in patients with chronic infections and carriers27,49 of HBV or LTBI, and also in patients with a history of HZ. Treatment with TNF inhibitors is associated with a small, but significant, increase in the risk of reactivation of the varicella zoster virus,21 especially in patients with weakened immune systems.

They should also be used with caution in patients who have lupus erythematosus or other autoimmune diseases27,49,50 and in patients with grade I-II NYHA HF.7 Finally, moderate to severe HF (NYHA III-IV) and the presence of demyelinating disease are absolute contraindications to their use.

Recommendation 17. When patients achieve remission, physicians should try to optimize the biologic drug regimen (decreasing doses or increasing intervals) with respect to the regimen specified in the Summary of Product Characteristics.

The current guidelines of the Psoriasis Group recommend prioritizing safety and consider optimization strategies to be appropriate in patients who achieve remission.50

DiscussionThis document, authored by the AEDV Psoriasis Group, offers a series of practical recommendations for the management of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in elderly patients. The initial list of recommendations was based on a review of the literature. These were submitted to a panel of experts, who reached consensus on the final proposal using the Delphi method.

The aim of these recommendations is to support decision-making by physicians and other professionals involved in the care process (pharmacists and/or managers), with the ultimate aim of improving health outcomes in elderly patients who have moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. The expert panel highlighted the importance of the following in this cohort: (1) evaluating the HRQoL of both patients and family members; (2) strengthening support measures and offering assistance with treatment; (3) simplifying the treatment regimen; and (4) considering biologic therapy, which has been shown to be a safer and more effective option than conventional systemic therapies.

Consensus was not reached on some of the statements considered in the Delphi study. Although there is evidence to support the efficacy and safety of phototherapy in elderly patients,21,51 consensus was not reached on its use as a first-line treatment in this setting. Similarly, although there is evidence supporting the efficacy and tolerability of treatment with dimethyl fumarate in these patients,52 the complexity of the dosage regimen, the elevated incidence of gastrointestinal AEs, and the need for periodic analytical monitoring53 make it difficult to consider this drug an ideal option in older patients. Finally, while the safety profile of apremilast may appear interesting in this age cohort,32 the complex initial dosing regimen, the high frequency of gastrointestinal AEs, and its relatively lower efficacy compared to biologic therapy54 limits its prioritization over other alternatives.

The present study has some limitations inherent in the methodology used, which bases consensus on the experience of an expert panel. The recommendations are based on the methodological procedure described, and their application should be contextualized within the Spanish healthcare system.

ConclusionsThis consensus exercise allowed us to define specific recommendations for managing moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in elderly patients. These recommendations will enable prescribing dermatologists to take decisions with greater confidence and will raise awareness about the available scientific evidence among other actors involved in the care of these patients.

FundingThe project was conceived and funded by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology with an unlimited grant from Almirall. No person connected with Almirall has participated in the development of the proposed recommendations or in drafting this manuscript.

The authors would like to thank the members of the AEDV Psoriasis Group for their contributions to the document and Outcomes’10 for their methodological support and coordination of the project.