The 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic can have an alarming impact on vaccination coverage. WHO, UNICEF and Gavi warn that at least 80 million children under the age of 1 are at risk of contracting diseases such as diphtheria, measles and polio due to the interruption of routine immunization and the temporary suspension of 93 campaigns of large-scale vaccination.

In Spain, a new healthcare scenario, which prioritizes telematics over in person, fear of contagion by going to health centers, and recommendations for physical distance and restricted mobility, reduce attendance at primary care centers. Despite recommendations established by the health authorities, vaccination coverage has decreased in all Autonomous Communities between 5% and 60%, depending on the age and type of vaccine. School vaccinations have been suspended and only vaccination of pregnant women against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis has been maintained. The decrease has been more evident for non gratuity vaccines: the first dose of meningococcal vaccine B has decreased by 68.4%in the Valencian Community, and Andalusia has observed a 39% decrease in the total doses of this vaccine and of 18% for that of rotavirus.

The recovering of vaccinations should be planned, organized and carried out in the shortest possible time.

This article discusses some aspects of the recovery of vaccination coverage for different groups: children, adolescents and adults, and patients at risk and in special situations.

La pandemia de la enfermedad por coronavirus 2019 puede tener un impacto alarmante en las coberturas de vacunación. La OMS, la UNICEF y la Gavi advierten de que al menos 80 millones de niños menores de 1 año corren el riesgo de contraer enfermedades como la difteria, el sarampión y la poliomielitis por la interrupción de la inmunización sistemática y la suspensión temporal de 93 campañas de vacunación a gran escala.

En España, un nuevo escenario asistencial, que prioriza lo telemático sobre lo presencial, el miedo al contagio por acudir a los centros sanitarios y las recomendaciones de distanciamiento físico y de movilidad restringida, reducen la asistencia a los centros de atención primaria. A pesar de las recomendaciones establecidas por las autoridades sanitarias, las coberturas vacunales han descendido en todas las comunidades autónomas entre un 5% y un 60%, dependiendo de la edad y del tipo de vacuna. Las vacunaciones en las escuelas se han suspendido y solo se ha mantenido, en general, la cobertura de la vacuna frente al tétanos, la difteria y la tosferina en las embarazadas. La disminución ha sido más manifiesta para las vacunas no financiadas: la primera dosis de vacuna antimeningocócica B disminuyó un 68,4% en la Comunidad Valenciana, y en Andalucía se observó un descenso de las dosis totales de esta vacuna (39%) y de la del rotavirus (18%).

La reanudación de las vacunaciones debe ser planificada, organizaday realizada en el menor tiempo posible.

En este artículo se comentan algunos aspectos de la recuperación de las coberturas vacunales para diferentes grupos: niños, adolescentes y adultos, y pacientes de riesgo y en situaciones especiales.

The coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is causing a severe worldwide medical, social and economic crisis. It is also having a worrying impact on vaccination coverage, to a degree which is alarming in countries with few resources. Situations are being reported of shortages of vaccines and other drugs, due to frontier closures and disruptions in air transport. Human, logistical and economic resources are being diverted to activities in connection with the pandemic, to try to flatten the infection curve. The WHO, UNICEF and Gavi warn that at least 80 million children under 1 year old run the risk of contracting diseases like diphtheria, measles and poliomyelitis as a result of the interruption to systematic immunisation and the temporary suspension of 93 large-scale vaccination campaigns (46 poliomyelitis vaccination campaigns and 27 against measles, among others). These three bodies urge that efforts be united to supply systematic immunisation services safely and continue with vaccination campaigns.1

In Spain, COVID-19 and the state of alarm announced on 14 March by the Government has affected the development of preventive and welfare programs. One of the programs most affected is the one for lifetime systematic vaccination in the common calendar.

A new medical scenario that prioritises remote attendance over face-to-face care except in emergencies, the fear of visiting medical centres and the recommendations for physical distancing and restricted mobility are the main causes which limit attendance in primary healthcare centres.

On 25 March 2020 the Ministry of Health announced the priorities of the vaccination program during the state of alarm due to COVID-19, including young infants up to the age of 15 months, pregnant women, the high risk population and post-exposure prophylaxis.2 On 23 April 2020 the Asociación Española de Vacunología,3 and one day later, a conjoint report by the Sociedad Española de Inmunología, the Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica and the Asociación Española de Pediatría,4 together with some autonomous communities,5,6 published a range of documents warning of the risks arising from failure to vaccinate or delaying vaccination. At the start of the de-escalation on 14 May 2020, the Health Ministry issued a new note urging the progressive recovery of vaccination activity, underlining the fall in the coverage of children and the risk this creates for public health.7 Unlike the first document, this second one reminds the population as well as medical professionals that vaccination is an essential health service provided by the health system, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, to protect the whole population against vaccine -preventable diseases.

In spite of these recommendations, vaccination coverage has fallen in all of the autonomous communities by from 5% to 60%, depending on age and the type of vaccine.8 Vaccinations in schools have been suspended and in general only the coverage of pregnant women has been maintained for the vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria and whooping cough (Tdpa).8 In Andalusia in March 2020 a fall of several points was observed for all doses of vaccines in children under 15 months old in comparison with March 2019: from 8% to 13% in the first vaccination at from 2 to 4 months (hexavalent, pneumococcal or meningococcal C), a 15% fall in the booster dose at 11 months (hexavalent and pneumococcal), 12% in the triple viral vaccine and meningococcal ACWY at 12months, and a fall of 20% in varicella vaccination at 15 months; the vaccination of pregnant women against whooping cough was not affected (−0,6%).8 The fall was clearest in unfinanced vaccines: administration of the first dose of meningococcal B vaccine fell by 68.4% in April in the Valencian Community, and in Andalusia a fall in the administration of total doses of this vaccine fell by 39%, while those of rotavirus fell by 18%.8,9 The fall in coverage was accentuated with age: for example, in the Valencian Community vaccination against tetanus and diphtheria (Td) in adults fell by 67.5% in those aged over 65 years in April 2020.9 It has to be pointed out that in private paediatrics the same effects do not seem to have occurred, and vaccination coverage here has been maintained.10

This fall in vaccination coverage, if it is maintained over time, may lead to the resurgence of infectious diseases (measles, pneumococcal and meningococcal diseases, etc.) by creating pockets of vulnerable individuals, above all once they start to return to kindergartens and schools, when it is no longer feasible to maintain physical distancing the whole time.

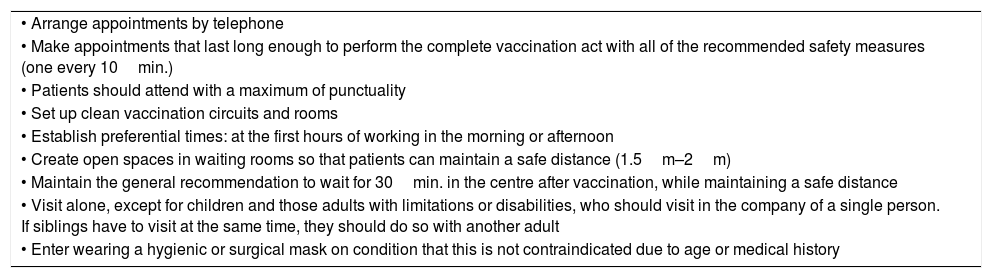

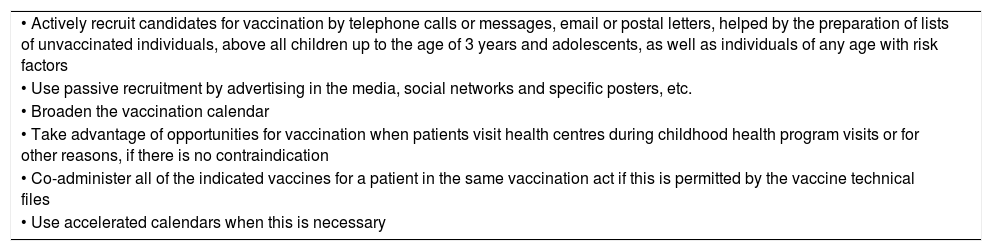

The act of vaccination must always be carried out by medical professionals; under no circumstances may it be delegated to other persons, and it will be performed while complying with all safety measures (Table 1). In cases where doses have been delayed, they will be given rapidly, i.e., obeying the minimum interval between doses, as the so-called accelerated calendars indicate, and taking authorised co-administrations into account. Recommencing vaccinations must be planned and organised, using different resources for activation of this task (Table 2).

Measure for safe vaccination in health centres.

| • Arrange appointments by telephone |

| • Make appointments that last long enough to perform the complete vaccination act with all of the recommended safety measures (one every 10min.) |

| • Patients should attend with a maximum of punctuality |

| • Set up clean vaccination circuits and rooms |

| • Establish preferential times: at the first hours of working in the morning or afternoon |

| • Create open spaces in waiting rooms so that patients can maintain a safe distance (1.5m–2m) |

| • Maintain the general recommendation to wait for 30min. in the centre after vaccination, while maintaining a safe distance |

| • Visit alone, except for children and those adults with limitations or disabilities, who should visit in the company of a single person. If siblings have to visit at the same time, they should do so with another adult |

| • Enter wearing a hygienic or surgical mask on condition that this is not contraindicated due to age or medical history |

Measures for the recovery of vaccination rates.

| • Actively recruit candidates for vaccination by telephone calls or messages, email or postal letters, helped by the preparation of lists of unvaccinated individuals, above all children up to the age of 3 years and adolescents, as well as individuals of any age with risk factors |

| • Use passive recruitment by advertising in the media, social networks and specific posters, etc. |

| • Broaden the vaccination calendar |

| • Take advantage of opportunities for vaccination when patients visit health centres during childhood health program visits or for other reasons, if there is no contraindication |

| • Co-administer all of the indicated vaccines for a patient in the same vaccination act if this is permitted by the vaccine technical files |

| • Use accelerated calendars when this is necessary |

Vaccination coverage must be recovered as soon as possible, fundamentally before the arrival of the anti-influenza vaccination campaign, as this usually overwhelms primary care vaccination surgeries during several weeks, as well as because of possible rises in COVID-19 incidence. Certain aspects of this recovery for children, adolescents and adults are described below, as well as for patients in risk groups or special situations.

The vaccination of childrenIn the gradual return to the “new normality” it is also reasonable to set priorities, above all for the first weeks. Firstly, vaccinations in the official calendar for children up to 3 years old and above all up to 15 months old must be given priority, giving all of the doses that were missed in recent months and, if necessary, using rescue calendars or accelerated ones specifically for children.11,12

On the other hand, in normal practice it is in this age group that more non-systematic vaccinations are administered (such as meningococcal B and rotavirus vaccines), so that it is recommended that planned vaccinations are used as far as possible to administer these vaccines, which are usually recommended by paediatricians and endorsed by scientific societies.

Respecting rotavirus vaccine, it has to be underlined and remembered that both available vaccines have limiting dates for the start and finish of their administration guideline, so that they cannot be delayed. The monovalent vaccine must be finished at 24 weeks old. The first dose of the pentavalent vaccine must not be given after 12 weeks old, and the guideline may finalise at up to 32 weeks of life.

Vaccination in adolescentsAdolescents generally have lower vaccination coverage than is the case during childhood, among other reasons because of the singular aspects of this life stage (rarely visiting hospitals, independence, etc.). During the pandemic adolescent vaccination was interrupted for a time and schools were closed, and it is in the latter where in many autonomous communities vaccines in the official program are administered to this age group, so that the reduction in coverage here has been highly significant.13

The recommended vaccines at 12 years old, according to the 2020 Ministry of Health calendar,14 are meningococcal conjugate vaccine, varicella vaccine for those who had not been vaccinated in infancy or had not had the disease, and human papilloma virus for girls. A dose of Td must be given at 14 years old.

Respecting meningococcal ACWY vaccination, the Ministry of Health decided to start a rescue vaccination campaign in the cohorts born from 2001 to 2006, due to the increased incidence of serum groups W and Y invasive meningococcal disease. This measure aims to achieve direct as well as indirect protection, as a peak in nasopharyngeal colonisation occurs in adolescents and young adults. To achieve this objective it is necessary to vaccinate simultaneously in all of the autonomous communities, and to achieve high rates of coverage in a short period of time.

The impact of the fall in coverage among adolescents and young adults to achieve community protection and the increase in invasive meningococcal disease by serum group W in infancy, as has occurred in other countries around Spain, may make it necessary to adopt other vaccination strategies, such as vaccinating breast-feeding babies and at 12months old.

In the current situation an effort must be made to recover vaccination and prevent pockets of susceptible populations from growing. To do this it would be advisable to undertake the active recruitment of adolescents, visiting health centres with a previously arranged appointment, using safe spaces and facilitating the co-administration of vaccines if their technical properties allow this.

Adult vaccinationThe main universally indicated vaccines for adults are those for influenza, pneumococcus and a booster dose for Td.14 Other vaccines are administered in case of susceptibility to a disease that can be prevented by vaccination, belonging to a risk group, or pregnancy. Notes released by the Ministry of Health on 25 March and 14 May prioritise vaccination against whooping cough for pregnant women as one of the immunisations that should not cease during the lockdown; this is the only reference to vaccinating healthy adults in the said documents.2,7

On 5 May 2020 the Ministry of Health issued the influenza vaccination recommendations for the 2020–2021 season,15 stating that it is a priority in the context of the pandemic. The chief novelties of these recommendations include arterial hypertension as a reason for vaccination (as traditionally chronic cardiovascular disease had been included “excluding isolated arterial hypertension”) and more ambitious coverage targets were set: 75% for individuals aged over 65 years and medical and social workers, and 60% for pregnant women and the members of risk groups.

Isolated arterial hypertension has been described as one of the risk factors for suffering severe COVID-19.16 The latest publications also state that the influenza and pneumococcus viruses may cause co-infection with SARS-CoV-2.17,18 This means that vaccination against influenza and pneumococcus is a fundamental tool to prevent the results of possible joint infection by these microorganisms, especially in individuals who belong to risk groups for both diseases.

Vaccination against flu (and in general against pneumococcus) takes the form of a campaign that usually starts in October; most vaccines are administered during the first 4 weeks of the campaign. The number of vaccination acts in Spain during the said campaign amounts to approximately 5.5 million,19 and this figure may reach 7.3 million if the proposed coverage for this year is achieved. This datum (5.5 million in 2months) contrasts with the 3.4 million vaccination acts that take place during the childhood vaccination calendar during the entire year. This means that we have to properly plan this vaccination, and this planning has to include a contingency plan in case of an increase in the number of cases of COVID-19.

Different bodies have planned influenza vaccination during the next season. The National Advisory Committee on Immunization in Canada20 recommends including measured that ensure protection against COVID-19, including vaccinating in the open air or in the patient’s own vehicle, as has been done in the United States for some time. The Pan American Health Organisation21 prioritises influenza vaccination, and like other bodies, it recommends emphasising the need for an appointment, vaccinating in well-ventilated premises or in the open air, expanding working hours, holding vaccination sessions exclusively for older individuals or those with pathologies, and guaranteeing the maintenance of a safe distance. A mathematical model has also been prepared which evaluates the strategy of universal influenza vaccination, given the possibility of a combined COVID-19 and influenza epidemic next autumn.22,23

Due to all of the above considerations the 2020–2021 influenza vaccination campaign must be correctly planned and must start early. It must be supplied with resources, be flexible in its application and last as short as possible.

Finally, it is necessary to call the attention to care homes, where the highest rates of morbimortality have occurred during this pandemic (from 30% to 60% of the deaths recorded in the different countries of the European Union),24 and the importance of vaccinating their residents as well as the staff who look after them against influenza. It is indispensible to establish official vaccination coverage indicators for residents as well as staff, as only if we know the degree of coverage will it be possible to evaluate the need to improve it if necessary.

Vaccination in risk groups and special situationsDuring the current pandemic the messages given out by official institutions and healthcare professionals have centred above all on restricting social contacts and not going to medical facilities unless this were strictly necessary or for emergencies. These messages were even more insistent in the case of immunodepressed individuals or those in special medical circumstances, given that in their condition complications secondary to COVID-19 could be even greater.25 Thus from a social and medical viewpoint, the population and medical personnel significantly reduced the number of face-to-face visits, including those for vaccination, as in some cases they considered vaccination to be a non-essential that could be delayed in the majority of occasions.

In spite of the informative note published on 25 March by the Ministry of Health2 on the priority of vaccination in situations of immunodepression, such as patients who had received transplants or treatment with eculizumab, it is very probable that, as occurred during childhood, vaccination coverage of risk groups has been affected. This circumstance is worrying from an individual as well as a collective viewpoint, given that the most vulnerable individuals would not only benefit from being vaccinated according to a specific calendar,26 as they would also benefit from the group immunity created by childhood vaccination, as the risk of disease increases if the latter falls.27

To recover the rate of vaccination in immunodepressed patients and other risk groups it is necessary to regain their trust in the safety of medical centres and professionals. To this end we firstly have to change the conception of medical centres as high-risk places for infection, by showing that any possible risks have been minimised by a series of hygiene and safety measures.28 Immunodepressed patients therefore have to be informed about safe accesses to hospitals and health centres, the existence of waiting rooms where minimum safety distances are maintained and the possibility of making an appointment at opening time in the morning or afternoon, with more time between appointments to reduce contact with other people or potentially contaminated elements in the environment.

Secondly, optimising the visits in connection with vaccinations will reduce the contact between these patients and the healthcare environment, as well as lost opportunities for vaccination.29 Vaccine co-administration, making appointments in health centres or vaccination units that coincide with those for other specialities or dispensing medicines in a hospital pharmacy, as well as performing serological tests in the surgery itself, will therefore all be good vaccination practice.

Thirdly, the role of professionals in setting an example has always been a key element in medical education. When professionals are seen by patients to behave in a positive way, this increases the probability that the latter will behave similarly.30 Hand hygiene should therefore be emphasised, together with correct use of the mask, the safety distance and proper cleaning and disinfection of surfaces and clinical material, with the aim of displaying these good practices and showing that the medical environment is a safe one.

Lastly, the general population and most especially risk groups have learnt a lesson from this pandemic, and this is the importance of vaccines as a basic tool in remaining healthy. COVID-19 and its consequences are a clear example of what happens when an infection is new and there are no vaccines when the population has no immunity against it. This perception has led to a popular demand for a vaccine that, as vaccinologists, we should use to show the value of known vaccines and vaccination for patients who belong to groups at risk.

Vaccination of those who have suffered COVID-19 and their close contacts is a special situation that has to be considered.7 The following recommendations have been made:

- •

No medical contraindications are known against vaccinating individuals who have recovered from COVID-19. It is not necessary to wait for any specific time. Nevertheless, to minimise the risk of transmission it is recommended that vaccination be postponed until after the recommended number of days of isolation, on condition that the symptoms have remitted.

- •

The close contacts of a confirmed case may be vaccinated once the quarantine period is over without their having developed symptoms.

- •

In some exceptional situations vaccination should not be delayed, such as when there is a short and specific period of time for administration, as otherwise the opportunity of timely vaccination may be lost, reducing its efficacy; for example, the Tdpa vaccine in pregnant women in weeks 27 and 28, together with post-exposure prophylaxis.

Now more than ever it is important to maintain a high level of vaccination coverage, as it is of capital importance to prevent the resurgence of diseases. It is evident that the eruption of SARS-CoV-2 has led to profound social changes, as a result of which the general attitude of the population and of individuals to the prevention and control of diseases that can be prevented by vaccination has changed. The change is so great that even specific vaccination campaigns against poliomyelitis in Africa have been interrupted, creating a dangerous critical point for the three-decade long worldwide drive to eradicate and eliminate the poliovirus.31 The suspension of vaccination activities against measles in more than twenty countries is making the situation worse in those countries where this disease was not under control.32

For the first time in modern history the world is faced by a coronavirus pandemic and a simultaneous epidemic of seasonal influenza. There is therefore a unique need now to revitalise trust in vaccinations, for medical professionals to work actively in encouraging vaccination, for citizens to act as the fundamental means of obtaining community protection and for researchers to develop new vaccines, playing a crucial role in this mission. When we have one or several effective and above all safe vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, this may generate enough confidence to overcome any reluctance to use this and the other vaccines, if it is accompanied by transparent information and education campaigns which include governments, medical professionals, public health services and the social media. Now is the time.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FAML declares that they form part of the editorial committee of the journal VACUNAS.

Please cite this article as: Moraga-Llop FA, Fernández-Prada M, Grande-Tejada AM, Martínez-Alcorta LI, Moreno-Pérez D, Pérez-Martín JJ. Recuperando las coberturas vacunales perdidas en la pandemia de COVID-19. Vacunas. 2020;21:129–135.