The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has resulted in huge morbidity and mortality since its onset in 2019. By June 24, 2023, only 32.2% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose. This paper explores the perceptions and trust of vaccine refusers based on the thematic analysis.

MethodsIn this study, we used a descriptive qualitative research design to explore the perceptions of the persons who did not believe in receiving the COVID-19 vaccine in Iraqi Kurdistan. This approach allowed us to explore the COVID-19 vaccine issue in-depth. Individual interviews were conducted with 14 participants in Kurdistan, Iraq.

ResultsResults showed that the participants had a great fear of the serious side effects of COVID-19 vaccines. Some believed that the virus was not natural and had been made by humans for different reasons including making profits from vaccines. Some believed that there was a silver material inside the vaccine that would force people to receive more doses in the future. Few believed that receiving COVID-19 vaccines was crossing the borders of God. Reinfection was a factor in selling more doses of vaccines. The participants were affected by the advice of the community and social media and not receiving the COVID-19 vaccines from healthcare workers, lack of responsibility from the government and companies, and not having trust in vaccines in this region.

ConclusionsConspiracy thinking, perceived negative effects, fear, reinfection, side effects of COVID-19 vaccines could be related to perceived vulnerability and seriousness among vaccine refusers.

El brote de la enfermedad por coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) ha provocado una gran morbimortalidad desde su inicio en 2019 en Wuhan. Sin embargo, para el 29 de junio de 2022, solo el 17,8% de las personas en países de bajos ingresos han recibido al menos una dosis. Este artículo explora las percepciones y la confianza de los que se niegan a vacunarse en un estudio cualitativo basado en el Modelo de Creencias en Salud.

MétodosEn este estudio, utilizamos un diseño de investigación cualitativo descriptivo para explorar las percepciones de las personas que no creían en recibir la vacuna COVID-19 en el Kurdistán iraquí. Este enfoque nos permitió explorar el tema de la vacuna COVID-19 en profundidad. Se realizaron entrevistas individuales con 14 participantes en Kurdistán, Irak.

ResultadosLos resultados mostraron que los participantes tenían un gran miedo a los efectos secundarios graves de las vacunas contra la COVID-19. Algunos creían que el virus no era natural y que los humanos lo habían creado por diferentes razones, incluida la obtención de ganancias con las vacunas. Algunos creían que había un material plateado dentro de la vacuna que obligaría a las personas a recibir más dosis en el futuro. Pocos creían que recibir vacunas contra el COVID-19 era cruzar las fronteras de Dios. La reinfección fue un factor en la venta de más dosis de vacunas. Los participantes se vieron afectados por los consejos de la comunidad y las redes sociales y no recibir las vacunas contra el COVID-19 de parte de los trabajadores de la salud, la falta de responsabilidad del gobierno y las empresas, y la falta de confianza en las vacunas en esta región.

ConclusiónDescubrimos que los que rechazan la vacuna COVID-19 en su mayoría temen efectos secundarios graves en el Kurdistán iraquí.

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has resulted in marked morbidity and mortality since its onset in 2019 in Wuhan. China. By June 21, 2023, there have been 768,187,096 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 6,945,714 deaths. As of 19 June 2023, a total of 13,461,344,203 vaccine doses have been administered.1

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that 70.3% of the world population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Each day 333,415 doses administered and 13.47 billion doses have been administered globally by June 24, 2023. However, only 32.2% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose. In terms of Iraq, it has been reported that by Jan 2, 2023, only 18.52% of the Iraqi population (7,944,775 of 42,899,221) have received the full doses of the COVID-19 vaccines.2

Vaccination is a highly effective strategy in decreasing severe illness and mortality from COVID-19 disease. The COVID-19 vaccines are safe and have low risks of severe adverse events.3–5 A study conducted in Kurdistan Region has shown that fatigue, injection site reactions, fever, myalgia, headache, and chills were the most reported side effects and in terms of the symptoms, most of them were mild to moderate.6 and fatigue (60%) and injection site reactions (55.8%) were the most common vaccine's side effects in Iraq.7

Low rates of taking up the COVID-19 vaccine are a major threat to the effects of vaccination in the prevention of disease and mortality from COVID-19. Populations across the globe are concerned about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines and their serious side effects.8–10 Two recent studies that examined vaccine hesitancy and public fear of the COVID-19 vaccines reported that the public has the fear of the COVID-19 vaccines11 and is concerned about the COVID-19 vaccines.12 WHO reported that only 26.8% and 18.8% have received the first and second dose of the COVID-19 vaccines by December, 24, 2022. The booster doses (third and fourth doses) were even lower; 0.65% and 0.01%, respectively.13

It is essential to explore the reasons why people refuse or hesitate to receive COVID-19 vaccines in a more detailed way. A qualitative study can help to extract more detailed factors contributing to vaccine refusal or hesitancy among the public. In this regard, we performed a qualitative study based on the Health Belief Model (HBM). The qualitative approach is adopted when we have little knowledge about the issues that we wish to examine.14 Examples of such issues are the perceptions and experiences of the persons who do not receive the COVID-19 vaccine in Iraqi Kurdistan. We adopted this research approach because it allowed us to explore the COVID-19 vaccine issue in-depth.15 In this regard, we aimed to explore the perceptions and trust of vaccine refusers in a qualitative study based on the thematic analysis in this paper.

MethodologyStudy designIn this study, we employed a descriptive qualitative approach to explore the perceptions of the persons who did not believe in receiving the COVID-19 vaccine using the Health Belief Model in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The HBM is widely used in understanding people's health behaviors. This model has the following constructs; perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy to engage in a behavior, and cues to action.16 In this model, perceived susceptibility is the belief about vulnerability to infection, while perceived severity is the belief about the negative impacts of the infection. In this regard, the perceived benefits of the COVID-19 vaccines are the persons' beliefs about being vaccinated, and perceived barriers are explained as the beliefs that the vaccination has some obstacles such as psychosocial, physical, or financial factors. Cues to action are information, people, and events that guide a person to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.16

Participants and settingsThe individuals were recruited through a purposive sampling technique and were invited to take part in an interview. The purposive sampling technique requires us to recruit individuals who can provide in-depth information about the examined issue.14 The invited persons were selected from different settings and both genders and various age groups to get a diverse group of sample. The participants had different religions (Islam, Yazidi, and Christian), gender (male and female), and occupations (doctor, public, teacher, academic, and businessmen) in Duhok city in Iraqi Kurdistan in 2021. The minimum age to meet the inclusion criteria was 18 years.

The semi-structured interviewing method was conducted with 14 participants in this study (see below for more details). The interviews with the individuals were performed after the verbal consent of the participants were received.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaAs previously mentioned, we attempted to include persons from different socio-demographic characteristics and social backgrounds. They were from both gender, different religions, social classes, and socioeconomic characteristics. The interviewer (the second author) contacted the persons through a snowballing sampling technique. Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling technique which is useful when it is more difficult to recruit hard-to-reach research participants.14 In this technique, the existing participants provide referrers to suitable samples required for a study. We were careful to ensure that the snowball sampling technique would not end up with a homogenous sample. The interviewer explained the aim of the study for the individuals to receive their permission for an interview. The interviewer requested an appropriate time for an interview following receiving personal permission for an interview.

ProceduresThe interviews were conducted by the second author (a Ph.D. student in nursing studies) between 6 May and 10 June 2021 through telephone. Due to restrictions with face-to-face contact, interviews through telephone were deemed appropriate. The interviewer encouraged the participants to determine an appropriate time for an interview. Before conducting the interviews, the consent form was verbally taken from all persons. The verbal consent of the participants was recorded in the phone call. Only two of the persons did not accept to participate in the study. The interviewer contacted two Christian persons several times, but they refused to participate in the study due to working load at a hospital and private sector. We aimed to include a diverse sample of the Kurdish population in this study. Therefore, we invited Christian persons to this study. The Kurdish population has three religions in Iraqi Kurdistan, including Islam, Yazidi, and Christianity. We supposed that these three religions have different perceptions of receiving COVID-19 vaccines. The interviewer explained the objectives of the study to the participants through a phone call. The responses of the participants to the questions were recorded on a mobile phone. The interviews lasted between 30 and 50 min

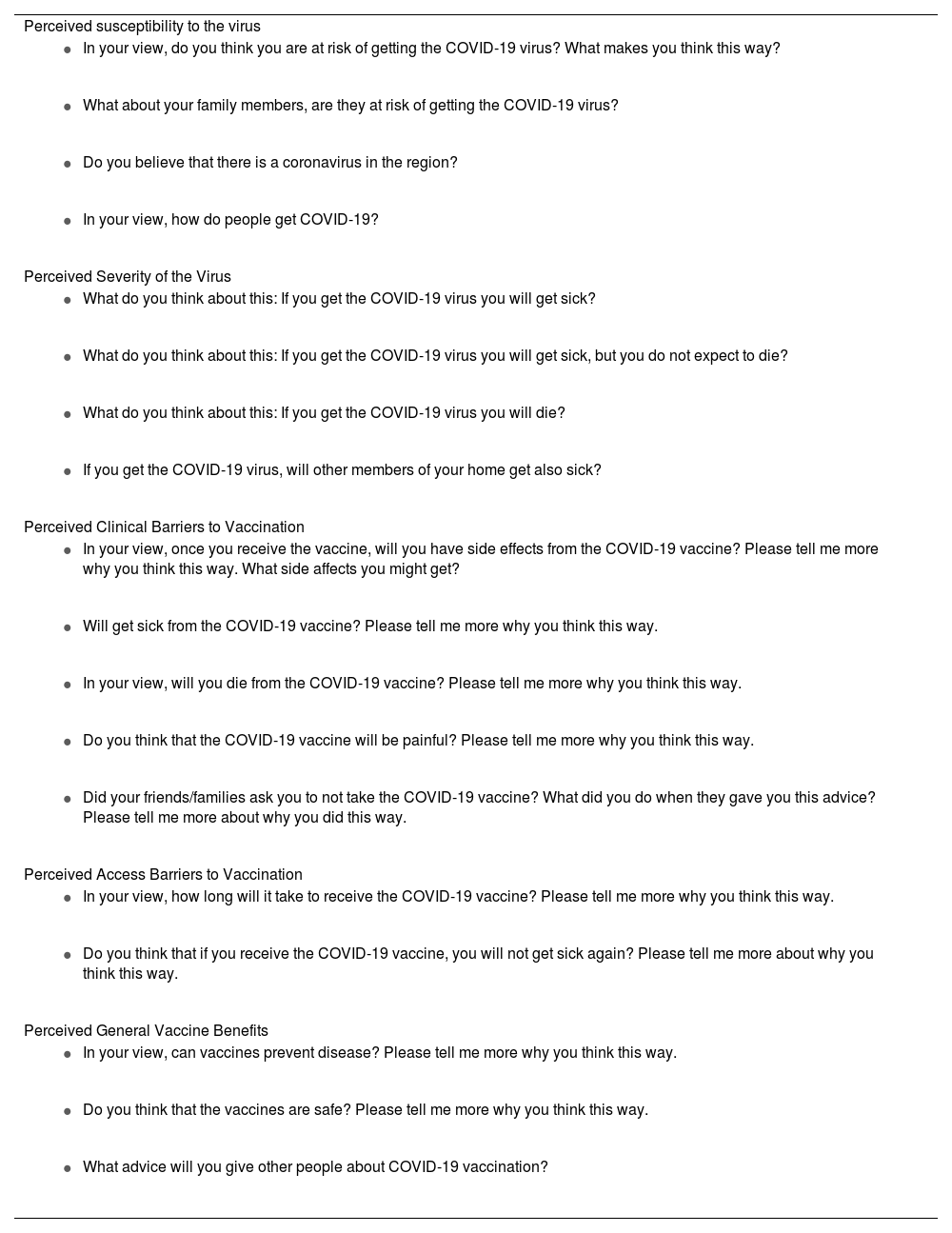

A semi-structured interviewing method was used to collect the information.14 Several open-ended questions were developed based on the HBM for the interviews. The questions of the study were established by the first and third authors. The questions were reviewed and arranged into five main opened-questions/themes as set out below.

Data collectionThe following general information was collected through the interview process with the participants. The information was age (years), gender, marital status, member of the family (how many, who are they?), educational attainment, religion, smoking, current employment/job situation, and healthcare worker or not.

The main questions of the study were developed based on the HBM concepts and were shown in Table 1. In the perceived susceptibility, we asked participants how much they feel that they are at risk of infection by COVID-19. In the perceived severity, we asked how much they get the infection. In the perceived clinical barriers to vaccination, we asked participants to explain how they feel that they affect by side effects in the case of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. In the perceived access barriers to vaccination, we asked the participants to explain the barriers to access to the COVID-19 vaccines in Iraqi Kurdistan. At the end, in the perceived general vaccine benefits, we asked the participants to explain the advantages of receiving the COVID-19 vaccines (Table 1).

Concepts of HBM and related questions about COVID-19 vaccination.

| Perceived susceptibility to the virus |

|

|

|

|

| Perceived Severity of the Virus |

|

|

|

|

| Perceived Clinical Barriers to Vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceived Access Barriers to Vaccination |

|

|

| Perceived General Vaccine Benefits |

|

|

|

The same pre-set questions were asked of all participants in this study. The interviewer asked the participants to answer the questions one by one with deep information. Probes and prompts were also used to elicit more information from the participants.14 The interviewer provided sufficient time for the participants to provide deep information and reasons.

Data analysisThe second author did all interviews in the Kurdish language. Then, the first author listened to and translated the interviews into English language. We analyzed the data based on the thematic qualitative method.14 The first author read and re-read the transcribed data to make sense of the data generated to identify suitable meanings and were coded accordingly. The initial codes were then used to form themes. The themes along with coding were submitted to the second and third authors for checking before final themes and sub-themes were organized.

Regarding the rigor of the data, the triangulation of researchers and peer review were used to ensure the credibility and accuracy of the findings. Triangulation is a technique used by researchers that more than one researcher collects or analyses the same research situation.14,17 Peer review is a process that is used during the data analysis period.14 The second and third authors reviewed all codes and themes conducted by the first author and the final themes and sub-themes were agreed upon by all authors. We did not use any analytical software for the arrangement of the data as we wanted to stay close to the data as much as possible.

EthicsThe verbal consent of the participants was obtained before data collection. The approval of this protocol was obtained from the University of Duhok. The confidentiality of the personal information of the participants was protected through the steps of the study. The participants were free to reject participation in the study based on the modified Declaration of Helsinki.

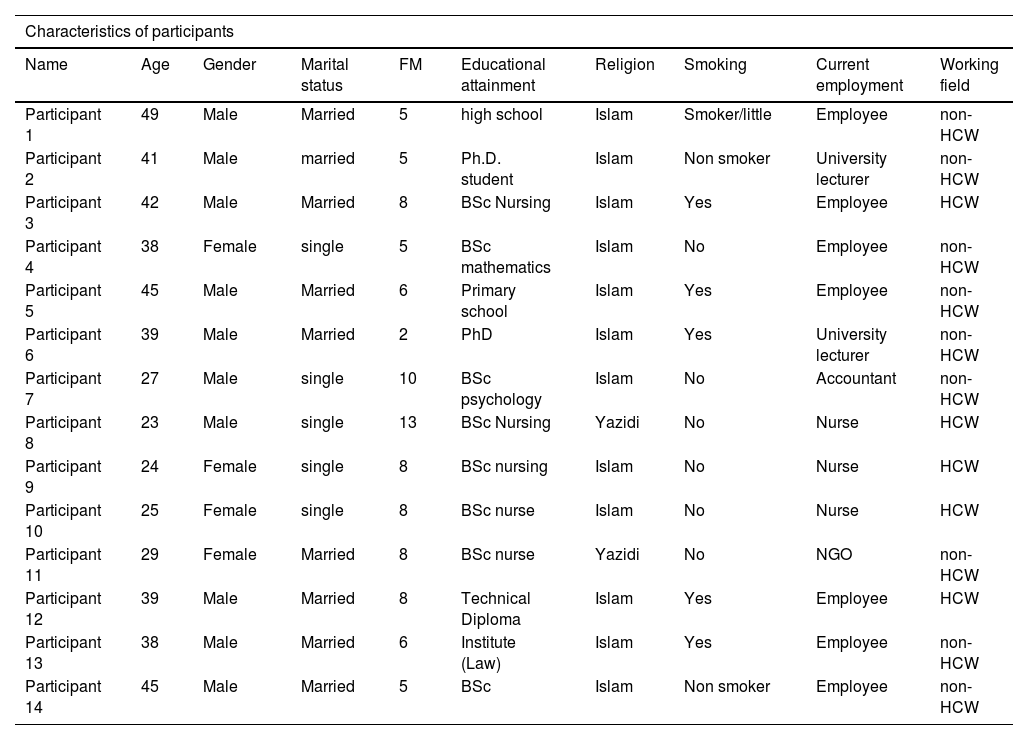

ResultsThe socio-demographic characteristics of the participants in this study are presented in Table 2. To protect the true identity of the participants, the name used in the findings are pseudo names.

General characteristics of participants.

| Characteristics of participants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Age | Gender | Marital status | FM | Educational attainment | Religion | Smoking | Current employment | Working field |

| Participant 1 | 49 | Male | Married | 5 | high school | Islam | Smoker/little | Employee | non-HCW |

| Participant 2 | 41 | Male | married | 5 | Ph.D. student | Islam | Non smoker | University lecturer | non-HCW |

| Participant 3 | 42 | Male | Married | 8 | BSc Nursing | Islam | Yes | Employee | HCW |

| Participant 4 | 38 | Female | single | 5 | BSc mathematics | Islam | No | Employee | non-HCW |

| Participant 5 | 45 | Male | Married | 6 | Primary school | Islam | Yes | Employee | non-HCW |

| Participant 6 | 39 | Male | Married | 2 | PhD | Islam | Yes | University lecturer | non-HCW |

| Participant 7 | 27 | Male | single | 10 | BSc psychology | Islam | No | Accountant | non-HCW |

| Participant 8 | 23 | Male | single | 13 | BSc Nursing | Yazidi | No | Nurse | HCW |

| Participant 9 | 24 | Female | single | 8 | BSc nursing | Islam | No | Nurse | HCW |

| Participant 10 | 25 | Female | single | 8 | BSc nurse | Islam | No | Nurse | HCW |

| Participant 11 | 29 | Female | Married | 8 | BSc nurse | Yazidi | No | NGO | non-HCW |

| Participant 12 | 39 | Male | Married | 8 | Technical Diploma | Islam | Yes | Employee | HCW |

| Participant 13 | 38 | Male | Married | 6 | Institute (Law) | Islam | Yes | Employee | non-HCW |

| Participant 14 | 45 | Male | Married | 5 | BSc | Islam | Non smoker | Employee | non-HCW |

The perceptions of participants towards COVID-19 vaccines were categorized into the following sub-themes.

Perceptions of COVID-19 and VaccinesIn terms of perceptions of the participants about COVID-19, the participants believed that there was a virus in the world, but they had negative perspectives about the COVID-19 virus and vaccines. Their perceptions included conspiracy thinking, religious beliefs, reinfection, and responsibility. The participants who refused to have the vaccine had diverse perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines. Some participants saw vaccines as commercial products rather than medicines. Many believed that the COVID-19 vaccines were dangerous and a life-threatening substance. They believed that COVID-19 vaccines would expose their life to an unknown path.

Conspiracy thinkingSome participants believed that this virus was not natural and made by humans for different reasons. Some powerful countries used this virus as a microbial war for the people. They expressed that great attention had been paid to this virus despite its similarity to other seasonal viruses. The vaccine had become a political and economic tool to break the economy of some countries or to decrease the price of oil. There were some competitions between countries. This virus had been made by humans to create the vaccine and sell it to other countries and people. One participant believed that the companies did not want to create a vaccine to eradicate the virus because they needed to sell the products to people for several years.

Participant 1 (non-HCW –healthcare worker) believed that there was a silver material inside the vaccine that would make people receive more doses in the future. This material was similar to receiving a narcotic and the human body asked for more amount of this material. Another participant believed that a chipset would be inserted into the body through the vaccine. Therefore, the global system could control the body system through this chipset. At that time, people would be like a robot.

Religious beliefsWe found some religious beliefs in terms of COVID-19 vaccines and viruses among the participants. Some participants remarked that the viruses were the natural way for making a balance in life. Humans aimed to destroy the balance made by God, but they could not do it. If someone received the COVID-19 vaccine, he/she would become the slave of the Antichrist.

Our prophet said that “You will see her deny it”. It means that you will see some things but they are not good for you. Or you will do some things that are not good for you. I think that if anyone receives the vaccine, after twenty or thirty years, he will be the slave of the “Antichrist” (Participant 12, HCW). One participant believed that the diseases which were created by humans would not affect all humans. He continued that what was happening today was under the control of God. Just God could change the current situation. No one knew what would happen tomorrow. He believed that death was under the control of God and no one could decrease or increase a minute of life. The age of each person would have been determined by God previously. The coronavirus would not kill anyone without the order of God. Just God could save human beings (Participant 12, HCW).

Another participant warned others not to cross the borders of God and receive the COVID-19 vaccine. He remarked that “the virus does not kill you when you are within the borders of God. The officials celebrated the end of the corona in Duhok, but they could not overcome the outbreak, because they crossed the border of the God”. He responded to the political and health authorities and celebrated the end of coronavirus in Duhok after the clearance of the first COVID-19 cases. Interestingly, one participant suggested that the virus is in the mind of people. She did not believe that this virus can be spread to another person and depends on the mentality of a person. She believed that the toxin or material does not affect the human body; it is mentality only.

COVID-19 vaccines as a commercial product and reinfectionSome participants reported that they were not at risk if they received the COVID-19 vaccine. But, they believed that the COVID-19 vaccines had been made for commercial purposes only. There were different reasons for that. One participant remarked: Because I see that receiving this vaccine will not be limited to one or two doses. These continuous doses will be a commercial issue and you need to purchase the vaccine shortly. Maybe the first doses are free, but the next doses will be a commercial product in the future.

The reinfection and lack of a guarantee from the companies was another reason mentioned by the participants who did not receive the vaccine. They believed that the COVID-19 vaccine was not safe because the patients would be infected again by this virus in contrast to past vaccines. The side effects of these vaccines might occur over time. It needed a year to clearly see the side effects.

Lack of sufficient responsibility by the governmentParticipants were skeptical about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine due to the lack of clear responsibility from the health sector. One participant reported that government officials were not ready to accept any responsibility for the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines. They did not informed people about the side effects of the vaccines. She remarked that: The governments cannot do anything in the case of mortality because they have signed an agreement with the companies.

The intention of the participants to receive the COVID-19 vaccine was affected by some factors, including beneficence of the COVID-19 vaccines, community, and family effects, and fear of receiving the vaccines.

Perceived negative effectsSome participants believed that the COVID-19 vaccines are not beneficial for humans. Because they believed that the vaccines do not eradicate the COVID-19 pandemic due to the changeability of the virus. In addition, the vaccines do not help persons to avoid being infected by this virus. They suggested that the COVID-19 vaccines are only effective for a short time. One participant reported that this virus can be found everywhere, so it is not controllable like hepatitis B and C.

Participants did not believe that COVID-19 vaccines lower the severity of the disease. It depends on the immunity of the person. Therefore, it does not help people in overcoming the disease. One nurse preferred to protect himself by using a mask rather than receiving the vaccine. He believed that the disease does not force the patients into hospitalization except for patients with chronic disease or weak immunity. The vaccine does not eradicate the virus. Because new people are getting infected by the virus and someone who receives the vaccine again will be infected by the virus and spread in the community. Maybe the virus is eradicated after 10 or 20 years (Participant 2, non-HCW).

For some participants, the main reason for refusing to have the vaccine was the use of the vaccine for a short time. They believed that the vaccines help them not to get cough when they need oxygen only. Some believed that the vaccines will just lower the severity of the disease.

Distrust within the communityIn terms of advising the participants or their advice to their families and friends to receive or not to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the participants had different ideas. Their intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine was influenced by the effects on the community and their family members. One participant advised the public to protect themselves by washing their hands, cleaning their surfaces, and disinfecting rather than receiving the vaccines due to the side effects of the vaccines. Interestingly, some participants remarked that their friends told them to not receive the vaccine. But one of them expressed that: We need to read the studies and not listen to everyone. We need to know the outcomes of the persons who have received the vaccine. Thousands of persons have received the vaccine and no one died because of the vaccine. Most of us ([HCWs] must receive the vaccine to create trust in the people (Participant 9, HCW).

Some participants were negligent about the effects of the COVID-19 vaccine. Others regretted seeing friends receiving the vaccine. For one participant, her main reason for this negligence was the COVID-19 vaccine weakened the level of immunity to some extent and that exposed the person to an infection.

It seems that some participants were influenced by some healthcare workers' opinions. One of them remarked that: I am at risk if I receive the [COVID-19] vaccine because some doctors reported that their health situations escalated following receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. The escalation of the health status of vaccine receivers was shown on TV several times. But I do not believe that I die following receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. This vaccine is for three or four months and again my immunity is decreased. Just the memory of the virus remains in my body (Participant 6, non-HCW).

The fear of the side effects of COVID-19 vaccines was another aspect that the participants refused or hesitated to receive it. Participant 8 (HCW) had a fear of blood clotting. He said: “Clotting is one of the side effects. It could go to the brain and make a stroke a person”. Some participants were concerned about the quality of the COVID-19 vaccine made by drug companies. They believed that the media hide the truth about the quality of the vaccine from the public.

Some other reasons for these side effects were not given a guarantee from the vaccine companies. They believed that the governments cannot do anything in the case of mortality because they have signed an agreement. The persons have to sign by their responsibility. The vaccines are safe for persons who have a strong mentality and a high level of immunity only. Even one of them advised the old people to not receive the vaccine: “Because they have weak immunity and their immunity will be weakened again. So, they may die due to other medical conditions” (Participant 2, non-HCW).

An expert in animal production suggested that “if someone has strong immunity and does not interact too much with other persons, it does not require to receive the vaccine”. He added that: I recommend that the [COVID-19] vaccines be produced based on the virus of this country, not based on the trains found in other countries. Otherwise, they would not be good vaccines for our people …. (Participant 6, non-HCW).

For this participant, it is possible to die after receiving the vaccine as well. The old persons who received the vaccine were infected by the virus and died consequently. The reason for the death is that the company has not reached the final version of the vaccine. The vaccine has side effects on humans.

One participant refused to receive the COVID-19 vaccine because he said that the current COVID-19 vaccines are under test: “We are the cases of this study, so we cannot trust these vaccines. But he refused the toxic material inside the vaccines” (Participant 2, non-HCW). He added that “all vaccines are so dangerous. It is not in my mind that the vaccine is useful and safe for humans. Few participants reported that the COVID-19 vaccines may not be good for persons with medical conditions such as hypertension. For example, Participant 13 (non-HCW) suggested screening before receiving the vaccine to explore who needs the COVID-19 vaccines.

Not having sufficient follow-up studies was another reason for the side effects of these vaccines. In this regard, they were scared of some serious complications like thrombosis after one or two years. Participant 8 (HCW) added that a person who received the COVID-19 vaccine was admitted to the ICU after 30 days. A participant said, “I saw a healthy 27 years old nurse in the USA that received the vaccine. But after receiving the vaccine, it was affected by a brain stroke. The right side of its body did not work”. The same concern was reported by Participant 10 (HCW) as well.

Social media effectsIt seems that videos on social made have made a fear among participants about not receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. For example, one of them reported that: “I am at risk [if I receive the COVID-19 vaccine]. I have seen many videos where some persons died after receiving the vaccine or their medical conditions escalated” (Participant 12, HCW). For participant 10 (HCW), he remarked that “I saw a video on social media that several persons who received the Pfizer vaccine in the UK were affected by thrombosis. Later I saw the same video in our formal media that approved that situation”. Some participants reported that their family members who were affected by these videos do not receive the vaccines.

Access to healthcare and justiceIn terms of access to healthcare and COVID-19 vaccines, some participants mentioned that the vaccine can be found everywhere (except for the Pfizer vaccine). But, they focused on not having justice for receiving the COVID-19 vaccines in their region. The officials come and receive the Pfizer vaccine and leave other COVID-19 vaccines for people. They mentioned that officials receive the Pfizer vaccine outside the normal process and registration. And registration in the region does not mean that there is justice in this country. For example, one participant from a local teaching hospital suggested that close to 4000 persons are in turn to receive the vaccine [mostly Pfizer vaccine is given in this center]. But if he wants AstraZeneca he can receive it tomorrow (Participant 14, non-HCW). One participant remarked that there is a fake certificate for COVID-19 in this country. (Participant 4, non-HCW).

Lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccinesIn terms of trust in the health system, different opinions were presented by the participants. They reported that the directorate of the health of this region does not see itself as a responsible organization. One participant did not trust the statistics the COVID-19 reported by the directorate of health. She believed that a considerable percentage of the people in the camps would die due to this virus, but they do not report it. Some participants presented their objections to the COVID-19 guidelines. For example, one of them said that these inconsistent guidelines are the source of the lack of trust in the COVID-19 vaccines among people.

The guidelines and the government's decisions are not suitable for the spread of Covid-19. For example, people can go to the Nawroz but they need to be at distance from each other. It is impossible to be far from each other in Nawroz. Several thousand people go outside the city for a picnic in Nawroz. Nawroz is the great national festival of the Kurdish people. It is celebrated on 21 March every year by close to 40 million Kurdish people globally. Also, people can go to the shopping center but we keep our distance from each other. It is again not possible to keep a distance from each other in Panorama [a big shopping center in Duhok city]. One participant remarked that:

I see this issue from the religious aspect. For example, the government said that there is no corona in the entire Ramadhan, but there is the corona in Eid [Eid is the celebration day after the end of the Ramadhan. It is celebrated by all Muslims across the world]. Three days of Eid were lockdown. Ok, after the lockdown I come to your Eid [so what is the difference] (Participant 12, HCW).

The way of infection of people may have made the lack of trust in the COVID-19 guidelines. In addition, not receiving the COVID-19 vaccines by health care workers could be one factor for the lack of trust in the COVID-19 guidelines and vaccines. A participant reported that a doctor who did not receive the vaccine advised one of his friends to receive it (Participant 12, HCW).

Alternative solutions to COVID-19 vaccinesSome advised the persons to protect themselves and increase their immunity by nutrition and do not receive the vaccine and not eat fast foods. The vaccines could be used for old persons who cannot walk and they should be made based on the strains of this region. A participant preferred to use herbal medicine rather than receive the COVID-19 vaccine (Participant 4, non-HCW). Participant 3 (HCW) said that people need to strengthen their immunity by nutrition and other methods. Some participants suggested that healthcare workers receive the vaccine for COVID-19 because they are at risk of the virus. This would encourage the public to receive the vaccine.

DiscussionThis study showed that the following factors less or more have a role in not receiving the COVID-19 vaccines by vaccine refusers in this region. The reasons for not receiving the COVID-19 vaccines back to constructs of perceived vulnerability and seriousness. The factors were conspiracy thinking, religious beliefs, perceived negative effects, distrust within the community to receiving the COVID-19, fear, access to healthcare and justice, COVID-19 vaccines as a commercial product, COVID-19 vaccine as a life-threatening material, reinfection, side effects of COVID-19 vaccines, social media effects, taking responsibility by the government, and lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines.

Some factors could be related to perceived vulnerability and seriousness among vaccine refuses in this region. We extracted the following factors from the themes explained in this study; community effect, conspiracy thinking, religious beliefs, and misinformation. A recent study conducted in this region reported that 77.03% of the healthcare workers (HCWs) have not received a COVID-19 vaccine. In addition, 41.46% are hesitant to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.12 The high prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among HCWs is a major concern for the health system, as they are trusted sources of health information for the general population. A nurse reported that I was a member of the vaccination team. We encouraged the general population to receive the COVID-19 vaccines, but our medical staff was not ready to receive the vaccines or some of them delayed receiving vaccine to receive the Pfizer vaccine. Therefore, the public was hesitant to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. The nurses suggested that the HCWs must receive the vaccine before other populations to raise the level of trust among the public. The HCWs are at a higher risk of infection in clinical settings compared to other populations, hence, it is anticipated that they are more willing for receiving the COVID-19 vaccines.3 We suggest that the health authorities mandate the HCWs for receiving the COVID-19 vaccines to raise the level of trust among people. Apart from the effects of HCWs on the public in receiving the COVID-19 vaccines, some families discourage their family members to not receiving the vaccines. This could be effective in a small percentage of society. But, mostly the HCWs have an impact on the public to receive or not receive the vaccines. Especially many people have a fear of the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines. In this regard, the HCWs can play a great role in providing trustful medical information to foster the public to receive the vaccines. The persons who had concerns about the side effects of a COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to be hesitant in receiving the vaccine in this region.12 Previous investigations have reported vaccines with unknown side effects have higher rejection rates.18 A global survey of 19 countries reported that 71.5% of the respondents would take a COVID-19 vaccine if it is proven to be safe and effective.19

Misinformation and conspiracy theories could be factors related to vaccine hesitancy.20,21 The participants believed that the virus is a virtual one and has been made by a powerful country to create the vaccines and sell to other countries. This is a popular belief among people that could be related to general beliefs or religious ones. Apart from this, some participants believed that death is under the control of God and no one can decrease or increase one minute of life. So, they believe that the COVID-19 vaccines do not assist them to relieve the disease severity. A recent study conducted in this region reported that the majority of hospitalized patients had not received the COVID-19 vaccines22 Another study indicated that COVID-19 vaccination is associated with approximately 70% lower likelihood of pneumonia and an 82% lower likelihood of requiring supplemental oxygen. Additionally, being vaccinated was shown to significantly reduce the risk of pneumonia and severe disease.23 In another study, it was reported that 14.0% of the people in Iraqi Kurdistan do not believe in the presence of the COVID-19 virus in the region, and 27.4% harbor conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 outbreak. They believe that COVID-19 could be a plot of or against the Kurdistan Regional Government, with percentages of 16.4% and 19.3% respectively 24.

It seems that spreading the misinformation about the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines has a role in escalating this conspiracy thinking because misinformation is one of the factors contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and the trust of the public. The fake information concerning the side effects of COVID-19 vaccines is circulating among populations.25 A study reported that fake news detection and health literacy scores in France are contributing to getting vaccinated against COVID-19 disease.26 The persons who enable to detect fake news are more likely to have higher rates of anti-vaccination or hesitancy.

Rumors and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 vaccines have devastating effects on vaccine coverage. A research project conducted by Vaccine Confidence Project in 2020 aimed to find out how online misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines affects vaccination intent.27 In this regard, participants were exposed to examples of misinformation in the United Kingdom and the United States which was circulated on Twitter. As an example, it was claimed that the COVID-19 vaccine changes DNA in humans and makes them infertile. The study showed that the exposure to this misinformation compared to factual information resulted in a decline in intent to vaccinate; including a 6.2% point drop in the United Kingdom and a 6.4% point drop in the US respondents.27 Other studies reported similar conclusions on the effect of exposure to online vaccine misinformation.28 We believe that conspiracy thinking of the people in Iraqi Kurdistan originates mostly from religion and low health literacy since the recent study of this region showed that the intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine is increased with an increasing level of education.12 Anyhow, we cannot ban the social media platforms, just the health system can work to provide and spread trustful medical information about COVID-19 vaccines through different platforms; including social media and web pages.

The most important effect of conspiracy thinking is that they cause too much fear, anxiety, and mistrust among people to receive the COVID-19 vaccines. Conspiracy theories impose narratives on sensitive situations such as wars, natural disasters, financial crises, and pandemics.29 For example, one of them believed that there is a silver material inside the vaccine insisting you receive more doses in the future. This belief and others like this one make fear the public to receive the vaccine. In agreement with our results, 20% of Americans believe that COVID-19 vaccines are used by the government to microchip the public. This shows that the public has concerned about digital surveillance and the commodification of personal data.30

But the prevailing belief is that the majority of participants believed that the COVID-19 vaccines are solely commercial products. The dysfunctional information ecosystem could accelerate the myths and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 disease or vaccines. But, the rumors about vaccine safety are spread through traditional media before spreading on online platforms.31 The studies have reported that believing in the man-made theory and business control theory substantially decreases the COVID-19 vaccine coverage.32,33 Religious beliefs could have an impact on the public to reject or receive the COVID-19 vaccine.34 Some religious leaders try to convince their followers to not receive the COVID-19 vaccine because they claim that the COVID-19 vaccines can cause homosexual tendencies and they can control the mind.35

A comprehensive analysis of 156 articles through a systematic review revealed that social media platforms have the potential to influence people's attitudes and behaviors regarding COVID-19 vaccination. This influence can be exerted through various means, such as spreading misinformation and creating online communities that promote behaviors contrary to public health recommendations. Additionally, social media can be utilized for public campaigns aimed at encouraging behaviors that may not align with the suggestions put forth by public health authorities.36 Given the existing challenges in achieving herd immunity, leveraging social media platforms to promote vaccine uptake is a notable approach. It is crucial to recognize that individuals' perceptions, which are influenced by the information they receive, play a significant role in shaping their intentions and behaviors regarding vaccination. By utilizing social media effectively, public health authorities can target and influence these perceptions to encourage positive attitudes and intentions towards vaccination. This can contribute to increasing vaccine uptake and ultimately help in combating the COVID-19 pandemic.37

A study conducted in the European Union, utilizing data from over 35,000 individuals on a weekly basis, examined the impact of trust on COVID-19 vaccination. The findings revealed a negative association between trust in science and COVID-19 vaccination, indicating that individuals with lower trust in scientific institutions were more likely to exhibit vaccine hesitancy. Conversely, trust in social media was positively associated with vaccine hesitancy, suggesting that individuals who had greater trust in social media platforms were more hesitant to get vaccinated. Furthermore, the study found that higher trust in social media was prevalent among specific demographics, including adults aged 65 and above, financially distressed individuals, and the unemployed. Vaccine hesitancy was primarily driven by conspiracy beliefs, indicating that individuals who held such beliefs were more likely to be hesitant about getting vaccinated. The study emphasizes the significance of trust as a key factor influencing vaccine hesitancy. It suggests that pro-vaccine campaigns should specifically target groups that are at a higher risk of hesitancy. Notably, individuals who relied on social media as their main source of information exhibited higher levels of vaccine hesitancy compared to those who relied on traditional media sources, largely due to the influence of conspiracy beliefs.38

Limitations of studyThe findings reported in this study must be interpreted in terms of the sampling technique and cultural aspects of this region. Some of the reasons reported by the participants in this region may be due to the cultural attitudes of the Kurdish population in this region. Therefore, these results are not generalized to other parts of Iraq and the world.

RecommendationsWe need the appropriate strategies to change the mind of the public to receive the COVID-19 vaccines because a low acceptance rate may pose a critical risk to the control of the COVID-19 pandemic. We need to focus on community-specific concerns or misconceptions and address historic issues breeding distrust. These strategies could be sensitive to religious or philosophical beliefs.39 These strategies need a deliberate collaboration among different stakeholders such as the government, religious leaders, and civil society.40

Receiving COVID-19 vaccines is mandatory for employees in Iraqi Kurdistan but not for students or the public. But, the public has to bring their COVID-19 vaccine card as a requirement for administrative affairs. This step is considered an indirect mandatory step to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. However, mandatory mRNA vaccines are a controversial issue.41 Multi-sectoral Approach (MSA) is a novel approach that has been recently suggested to increase the level of vaccine coverage. MSA is a deliberate collaboration among different stakeholders, groups, and sectors. In this approach, the stakeholders make coordinate with each other to not do the administrative affairs of individuals without having the COVID-19 vaccines card. In this regard, the governments get benefit from the strengths of different sectors to work together to achieve the shared goal of building trust in the COVID-19 vaccines.42 Also, the results obtained from snowballing sampling may not present show the real situation of the public. Therefore, large quantitative studies are suggested for the next attempts.

ConclusionsThis study found that the COVID-19 vaccine refusers mostly fear serious side effects in Iraqi Kurdistan. We found that the following factors could be related to perceived vulnerability and seriousness among vaccine refusers. The factors were conspiracy thinking, religious beliefs, perceived negative effects, distrust within the community to receiving the COVID-19, fear, access to healthcare and justice, COVID-19 vaccines as a commercial product, COVID-19 vaccine as a life-threatening material, reinfection, side effects of COVID-19 vaccines, social media effects, taking responsibility by the government, and lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

ContributionDeldar Morad Abdulah: Concept, study design, review, data arrangement, writing and analysis.

Hawar Abdulrazaq Mohammedsadiq: Data collection, interviews, recording, approval.

Pranee Liamputtong: Concept, review, analysis, editing, and approval.

The authors would like to express their deep thanks to the participants who participated in this study.