This study aimed to determine the attitudes and concerns of nursing students toward the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) vaccine, their willingness to be vaccinated, and the factors affecting their willingness in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

MethodThis cross-sectional study was conducted using an online questionnaire in 498 nursing students in Izmir. Chi-square test, Student’s t-test and binary logistic regression were used in data analysis.

ResultsDespite the fact that 64.5% of nursing students intended to be vaccinated against COVID-19, they expressed their attitudes and concerns about the lack of COVID-19 vaccination information (65.7%), its effectiveness (41.6%), and safety (45.8%). Students did not intend to be vaccinated due to insufficient trust in the vaccine effectiveness (84%), the continuous COVID-19 mutation. Strong predictors of nursing students' intention to be vaccinated in the logistic regression analysis; education level, family income perception, history of vaccination rejection in the past, confidence in the vaccine, the effectiveness of the vaccine, the side effects of the vaccine, seeing oneself as a guinea pig, and thinking that the vaccine will change the genetic structure were determined (p<0.05).

ConclusionNursing students are known to be future healthcare professionals and play a decisive role in counseling individuals in the community on the risks of COVID-19 and the benefits of the vaccine. Therefore, focusing on training that is aimed at increasing vaccine knowledge, eliminating their negative attitudes and concerns, and building confidence in vaccines is necessary.

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo determinar las actitudes y preocupaciones de los estudiantes de enfermería hacia la vacuna contra la enfermedad por coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19), su disposición a vacunarse y los factores que afectan su disposición en la segunda ola de la pandemia de COVID-19.

MétodosEste estudio transversal se realizó utilizando un cuestionario en línea en 498 estudiantes de enfermería en Izmir. En el análisis de datos se utilizaron la prueba de chi-cuadrado, la prueba t de Student y la regresión logística binaria.

ResultadosMientras que el 64.5% de los estudiantes de enfermería tienen la intención de vacunarse contra el COVID-19. Los estudiantes expresan sus actitudes y preocupaciones sobre la falta de información sobre la vacuna COVID-19 (65.7%), water efectividad (41.6%) y seguridad (45.8%). Los estudiantes no tienen la intención de vacunarse debido a la falta de confianza en la eficacia de la vacuna (84%), la mutación continua de COVID-19. Fuertes predictores de la intención de los estudiantes de enfermería de ser vacunados en el análisis de regresión logística; nivel educativo, percepción de los ingresos familiares, antecedentes de rechazo a la vacunación en el pasado, confianza en la vacuna, eficacia de la vacuna, efectos secundarios de la vacuna, verse a sí mismo como como como comodia un conej la estructura genética se determinarone (p<0.05).

ConclusiónSe sabe que los estudiantes de enfermería son futuros profesionales de la salud y juegan un papel decisivo en la orientación de las personas de la comunidad sobre los riesgos de COVID-19 y los beneficios de la vacuna. Por lo tanto, es necesario utilizar la capacitación que tiene como objetivo aumentar el conocimiento sobre las vacunas, eliminar sus actitudes negativas y sospechas, y generar confianza en las vacunas.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020, due to the emergence of the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. On the same day, the first official case in Turkey was confirmed.1 The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a public health crisis and socially, economically, and psychosocially affected the public social distancing, movement restrictions, public health measures (hygiene, face mask, and social distance), and social and economic measures have been taken against the pandemic. These measures were intended to play an important role in halting the spread of the pandemic while allowing a large part of the population to acquire natural immunity against the virus.2,3

These measures were also aimed to control the transmission until vaccines were readily available to the population. Vaccines have been proven to be the most successful and highly effective public health interventions to control and eradicate vaccine-preventable diseases, as well as reduce and prevent serious disability or death due to infectious diseases.2,4,5 However, for a safe and effective vaccination program to reach optimum effectiveness, high intake rates by the population are required.6–8

The concept of “vaccine hesitancy” is defined as the delay or refusal to accept the vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services and has been recognized as “one of the top 10 threats to global health” by the WHO.6 Vaccine reluctance remains a limiting factor in the global efforts to control the current pandemic with its adverse health and socioeconomic consequences.9,10 Healthcare providers (HCPs) are considered the most reliable source of information on vaccines and are expected to be aware of vaccination risks and benefits. Surprisingly, vaccine hesitancy has been confirmed among healthcare professionals (medical doctors, nurses, dentists, etc.). Studies showed that the rate of vaccine acceptance among nurses is low. A study conducted with HCPs (physicians, nurses, dentists, pharmacists, and health personnel) in Turkey revealed that approximately 84.6% of HCPs and 66.5% of nurses were willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine when available.11 Similarly, Hong Kong10 and Israel12 studies revealed that 63% and 61% of working nurses showed their willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19, respectively. Another study that was conducted among nursing students from 7 European countries (Greece, Albania, Spain, Cyprus, Italy, Czech Republic, and Kosovo) reported that 44% of participants would accept a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine.13

Main concerns that were described in previous studies included vaccine efficacy and safety, possible side effects, misinformation, religious beliefs, and personal freedom violations. These concerns have been also reinforced by different conspiracy theories that predominantly circulate on social media.13,14 The pandemic poses a great risk to HCPs who are often in direct contact with infected patients. Immunization would be vital to protect HCPs and control hospital-acquired transmission. HCPs have a key role in helping the public to overcome their vaccination doubts and concerns.2,10,13,15 Thus, as future HCPs, understanding and increased acceptance among nursing students toward the COVID-19 vaccine to manage the pandemic, both now and in the future, is very important.9 Vaccination acceptance by nursing students does not only protect them against the virus but is also a source of information on public immunization.9,10 Existing vaccine hesitancy studies among healthcare nursing students are very rare. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the attitudes and concerns of nursing students toward the COVID-19 vaccine, their willingness to be vaccinated, and the factors that affect their willingness in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

MethodDesign and settingThis cross-sectional study was conducted online during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic between February 1, 2021 and March 30, 2021. The sample of the study consisted of 1100 students who are enrolled in the Faculty of Nursing of a public university in the metropolitan city of Izmir. Out of 524 students who voluntarily participated in the study, a total of 498 students were included, whereas 26 students who had been vaccinated against COVID-19 were excluded because their willingness to be vaccinated can no longer be questioned. The COVID-19 vaccination program in Turkey started on January 14, 2021, with the Chinese-made inactivated vaccine Sinovac, which was to be administered in 2 doses to HCPs and the elderly over 65 years of age. Pfizer /BioNTech mRNA vaccines were introduced onto the vaccination program on April 2, 2021.1 By the time this study was conducted, nursing students had not been included in the national immunization program.

InstrumentsA questionnaire that was prepared by other researchers in line with the literature was used to collect data.9,16–18 It consisted of 3 parts. The first part included demographic characteristics (5 questions), history of chronic diseases and allergies, seasonal flu vaccination status in the last 2 years, vaccination rejection status for himself or his relatives until now (4 questions). The second part included COVID-19 risk perception, perceived COVID-19 impact on self-experiences and COVID-19 information sources and reliance on COVID-19 HCP statements, etc. (8 questions). The third part included attitudes and concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine (8 items) in 3 options (1=Agree; 2=Undecided, 3=Disagree), intention to get COVID-19 vaccine in 1 question (1=yes, 2=no, 3=undecided), and the reasons for not wanting to be vaccinated were asked with 1 question for those who answered “unwilling” and “undecided.” Opinions of 3 experts in the field of Public Health Nursing and Women's Health and Diseases nursing were taken for the questionnaire form, and arrangements were made in line with their suggestions.

Data was collected by sharing the online questionnaire form in the WhatsApp groups and during online course lectures in each class. Informed consent was obtained from the participants before moving on to the survey items on the survey platform. An average of 6–8 min is needed to fill out the survey.

Data analysisThe Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25.0 package program (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA) was used to evaluate the data. Mean (standard deviation), frequency, and percentage were used in the descriptive data, and the Chi-square test and Student’s t-test were used in data analysis. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed using the significant variables for further analysis of the factors that affect the COVID-19 vaccine intention. Those who had the intention to be vaccinated (1) and those who were “unwilling” and “undecided” (0) were coded. The Nagelkerke R2 value of the logistic regression model using the Enter method is 0.520. The significance level of P<.05 was accepted for all hypotheses.

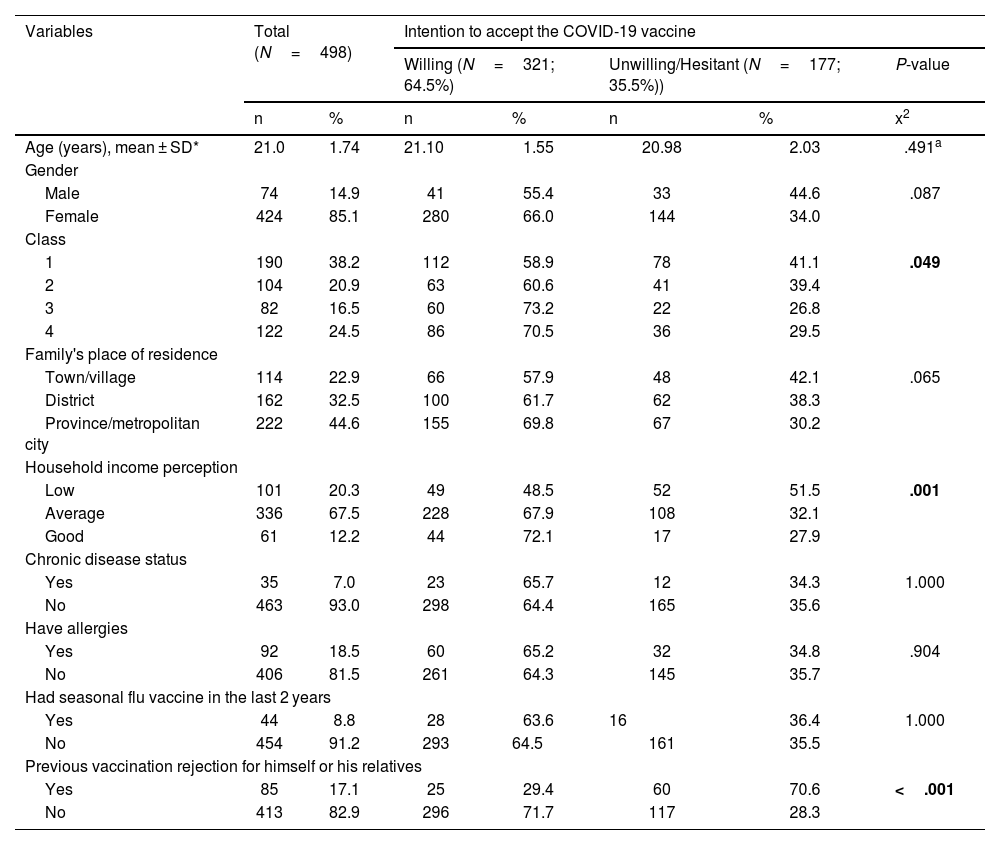

ResultsThe mean age of 498 nursing students, aged between 18 and 29 years, who participated in the study was 21.06±1.74 and the majority of them (85.1%) were female. The introductory characteristics of the students are presented in Table 1. Most nursing students (81.3%) think that the COVID-19 pandemic will continue for a long time, they view having COVID-19 infection as a moderate and very serious problem (90.6%), and 63.3% of them have the risk of contracting COVID-19 infection. COVID-19 infection was experienced by 8.2% of nursing students and the pandemic process affected the lives of many of them badly or very badly (87%). Most students (87.8%) follow the news about COVID-19 at a moderate and advanced level, and the primary sources of information (75.9%) are the WHO/Turkey Ministry of Health (MoH) Scientific Committee and social media (72.7%). However, 57.6% stated their trust in the explanations of HCPs (Table 2).

Individual characteristics of nursing students.a“

| Variables | Total (N=498) | Intention to accept the COVID-19 vaccine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing (N=321; 64.5%) | Unwilling/Hesitant (N=177; 35.5%)) | P-value | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | x2 | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD* | 21.0 | 1.74 | 21.10 | 1.55 | 20.98 | 2.03 | .491a |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 74 | 14.9 | 41 | 55.4 | 33 | 44.6 | .087 |

| Female | 424 | 85.1 | 280 | 66.0 | 144 | 34.0 | |

| Class | |||||||

| 1 | 190 | 38.2 | 112 | 58.9 | 78 | 41.1 | .049 |

| 2 | 104 | 20.9 | 63 | 60.6 | 41 | 39.4 | |

| 3 | 82 | 16.5 | 60 | 73.2 | 22 | 26.8 | |

| 4 | 122 | 24.5 | 86 | 70.5 | 36 | 29.5 | |

| Family's place of residence | |||||||

| Town/village | 114 | 22.9 | 66 | 57.9 | 48 | 42.1 | .065 |

| District | 162 | 32.5 | 100 | 61.7 | 62 | 38.3 | |

| Province/metropolitan city | 222 | 44.6 | 155 | 69.8 | 67 | 30.2 | |

| Household income perception | |||||||

| Low | 101 | 20.3 | 49 | 48.5 | 52 | 51.5 | .001 |

| Average | 336 | 67.5 | 228 | 67.9 | 108 | 32.1 | |

| Good | 61 | 12.2 | 44 | 72.1 | 17 | 27.9 | |

| Chronic disease status | |||||||

| Yes | 35 | 7.0 | 23 | 65.7 | 12 | 34.3 | 1.000 |

| No | 463 | 93.0 | 298 | 64.4 | 165 | 35.6 | |

| Have allergies | |||||||

| Yes | 92 | 18.5 | 60 | 65.2 | 32 | 34.8 | .904 |

| No | 406 | 81.5 | 261 | 64.3 | 145 | 35.7 | |

| Had seasonal flu vaccine in the last 2 years | |||||||

| Yes | 44 | 8.8 | 28 | 63.6 | 16 | 36.4 | 1.000 |

| No | 454 | 91.2 | 293 | 64.5 | 161 | 35.5 | |

| Previous vaccination rejection for himself or his relatives | |||||||

| Yes | 85 | 17.1 | 25 | 29.4 | 60 | 70.6 | <.001 |

| No | 413 | 82.9 | 296 | 71.7 | 117 | 28.3 | |

*SD: Standard deviation, “x2” Chi-square test.

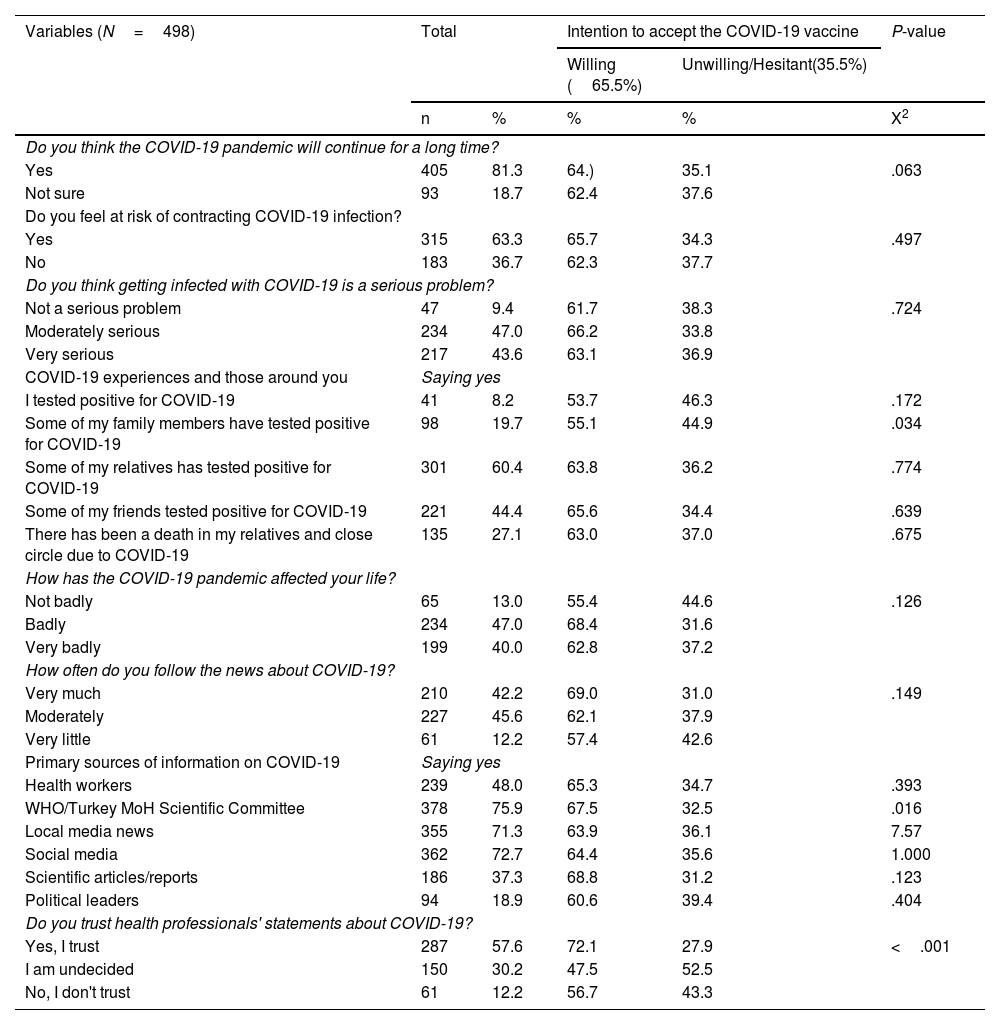

Nursing students' perceptions and experiences of COVID-19 infection risk and information sources.

| Variables (N=498) | Total | Intention to accept the COVID-19 vaccine | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing (65.5%) | Unwilling/Hesitant(35.5%) | ||||

| n | % | % | % | X2 | |

| Do you think the COVID-19 pandemic will continue for a long time? | |||||

| Yes | 405 | 81.3 | 64.) | 35.1 | .063 |

| Not sure | 93 | 18.7 | 62.4 | 37.6 | |

| Do you feel at risk of contracting COVID-19 infection? | |||||

| Yes | 315 | 63.3 | 65.7 | 34.3 | .497 |

| No | 183 | 36.7 | 62.3 | 37.7 | |

| Do you think getting infected with COVID-19 is a serious problem? | |||||

| Not a serious problem | 47 | 9.4 | 61.7 | 38.3 | .724 |

| Moderately serious | 234 | 47.0 | 66.2 | 33.8 | |

| Very serious | 217 | 43.6 | 63.1 | 36.9 | |

| COVID-19 experiences and those around you | Saying yes | ||||

| I tested positive for COVID-19 | 41 | 8.2 | 53.7 | 46.3 | .172 |

| Some of my family members have tested positive for COVID-19 | 98 | 19.7 | 55.1 | 44.9 | .034 |

| Some of my relatives has tested positive for COVID-19 | 301 | 60.4 | 63.8 | 36.2 | .774 |

| Some of my friends tested positive for COVID-19 | 221 | 44.4 | 65.6 | 34.4 | .639 |

| There has been a death in my relatives and close circle due to COVID-19 | 135 | 27.1 | 63.0 | 37.0 | .675 |

| How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your life? | |||||

| Not badly | 65 | 13.0 | 55.4 | 44.6 | .126 |

| Badly | 234 | 47.0 | 68.4 | 31.6 | |

| Very badly | 199 | 40.0 | 62.8 | 37.2 | |

| How often do you follow the news about COVID-19? | |||||

| Very much | 210 | 42.2 | 69.0 | 31.0 | .149 |

| Moderately | 227 | 45.6 | 62.1 | 37.9 | |

| Very little | 61 | 12.2 | 57.4 | 42.6 | |

| Primary sources of information on COVID-19 | Saying yes | ||||

| Health workers | 239 | 48.0 | 65.3 | 34.7 | .393 |

| WHO/Turkey MoH Scientific Committee | 378 | 75.9 | 67.5 | 32.5 | .016 |

| Local media news | 355 | 71.3 | 63.9 | 36.1 | 7.57 |

| Social media | 362 | 72.7 | 64.4 | 35.6 | 1.000 |

| Scientific articles/reports | 186 | 37.3 | 68.8 | 31.2 | .123 |

| Political leaders | 94 | 18.9 | 60.6 | 39.4 | .404 |

| Do you trust health professionals' statements about COVID-19? | |||||

| Yes, I trust | 287 | 57.6 | 72.1 | 27.9 | <.001 |

| I am undecided | 150 | 30.2 | 47.5 | 52.5 | |

| No, I don't trust | 61 | 12.2 | 56.7 | 43.3 | |

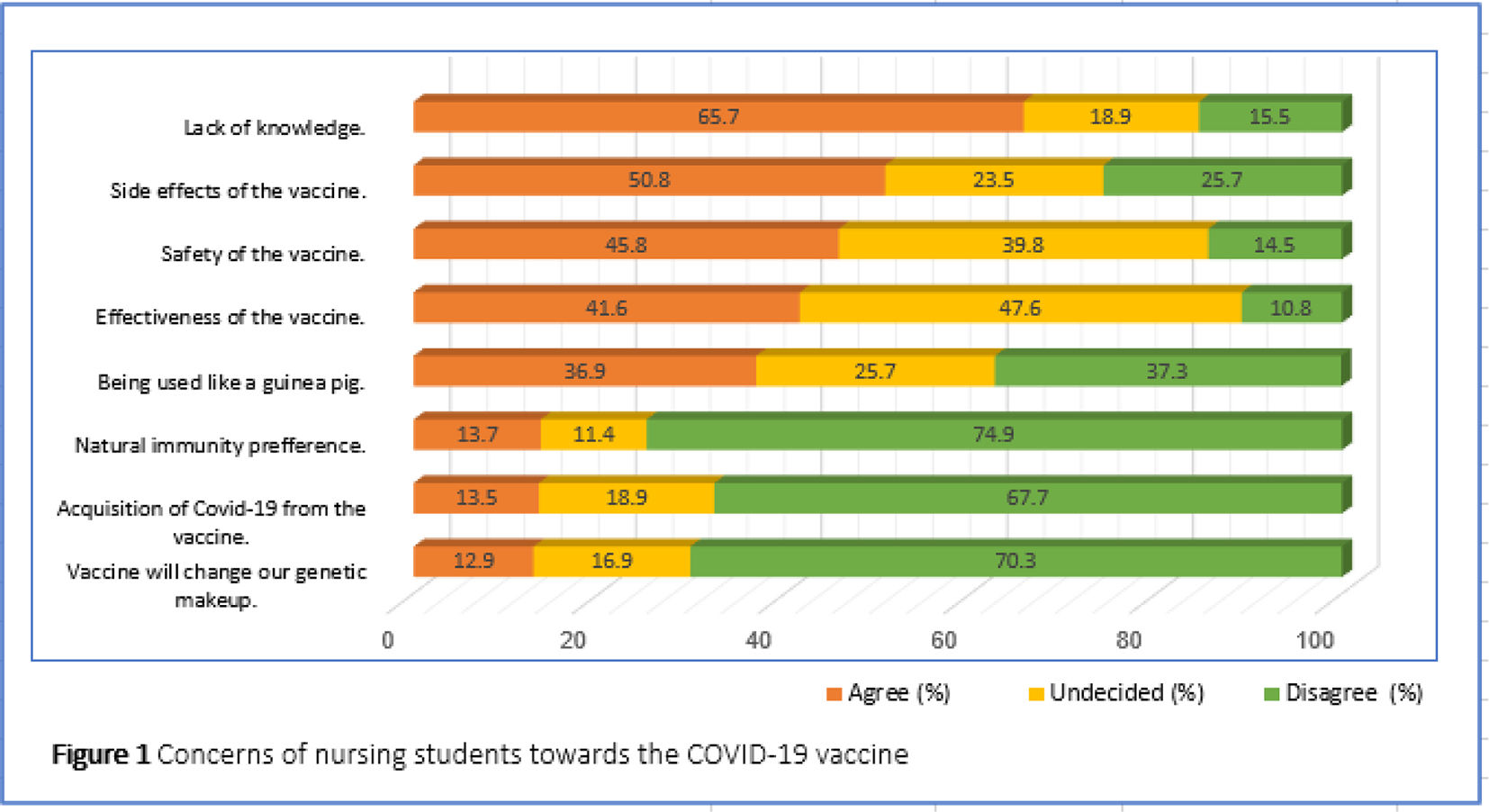

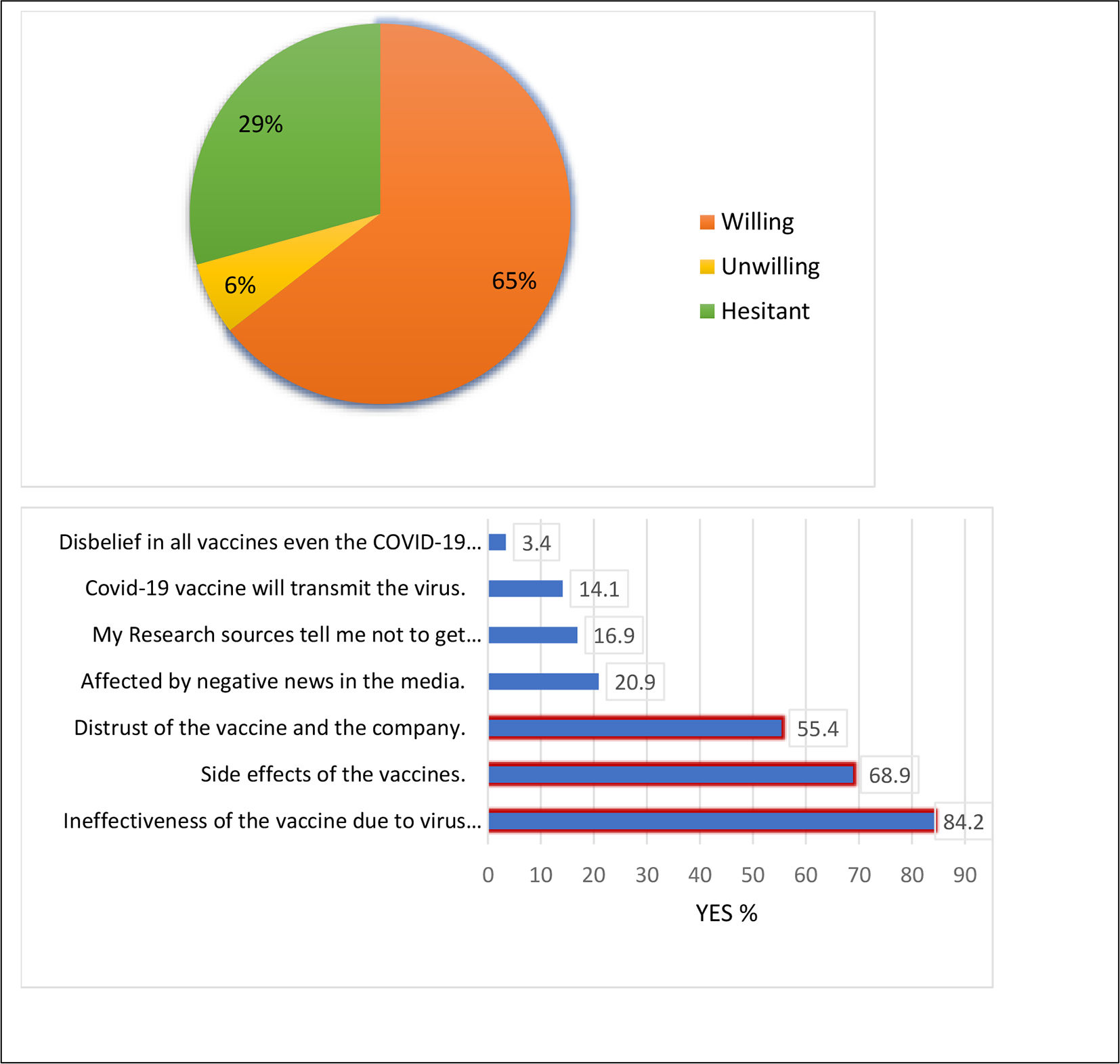

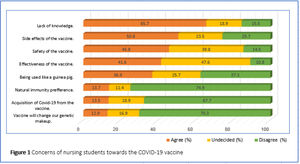

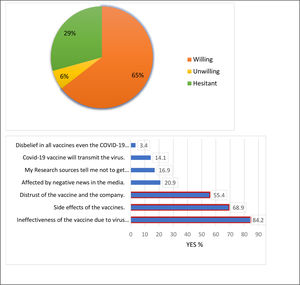

Nursing students reported that the information about the current COVID-19 vaccine was insufficient (65.7%), the side effects of the vaccine (50.8%), the effectiveness of the vaccine (41.2%), and the safety of the vaccine (45.8%) (Fig. 1). While 64.5% of students were willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19, 35.5% are unwilling (6.2%) and hesitant (29.3%). Among the reasons provided for their hesitation or unwillingness, insufficient trust in the vaccine's efficacy (84%) due to COVID-19 virus mutation was prominent (Fig. 2).

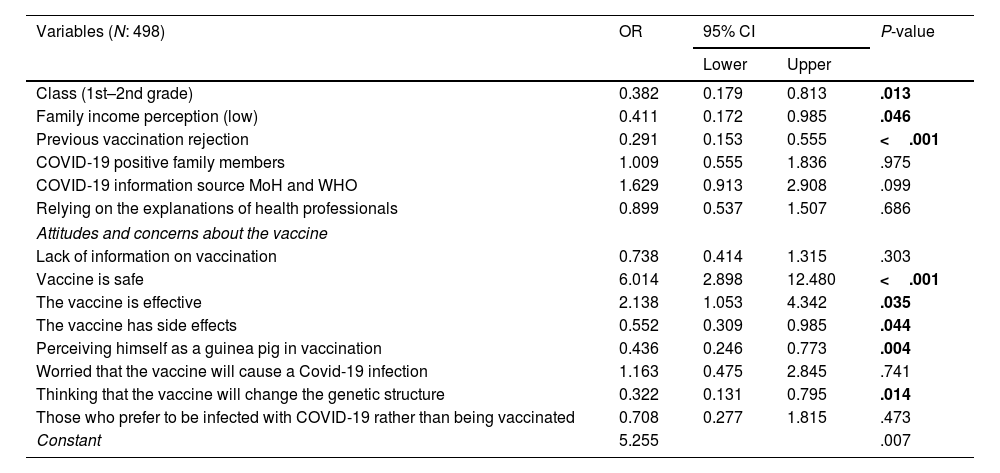

Factors associated with the intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19The analysis conducted using independent variables to determine the factors that affect the intention of nursing students to be vaccinated against Covid-19 revealed a significant difference between the attitudes and concerns (8 items) related to vaccines, such as class, perception of family income, previous vaccination rejection, family members having COVID-19 infection, with the WHO/MoH Scientific Committee as primary sources of COVID-19 information, relying on HCP COVID-19 statements (P<.05) (Tables 1, 2). The logistic regression analysis using significant variables showed a negative effect on 1st–2nd grade students (odds ratio [OR]=1.909, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.113–3.276; P<.05) and students who had had previously rejected vaccination (OR=3.405, 95% CI=1.788–6.485; P<.001) on the intention to be vaccinated. Confidence in the vaccine based on the attitudes and concerns of the students (OR=6.014, 95% CI=2.898–12.480; P<.001) and the effectiveness of the vaccine (OR=2.138, 95% CI=1.053–4.342; P<.05) were positive determining factors. On the other hand, factors such as vaccination side effects (OR=1.811, 95% CI=1.022–3.211; P<.05), seeing oneself as a guinea pig in vaccination (OR=2.268, 95% CI=1.288–3.993; P<.05), and thinking that the vaccine will alter the genetic structure (OR=2.867, 95% CI=1.167–7.047; P<.05) are factors that negatively affect nursing students' vaccination intention (Table 3).

Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine intention among nursing students by binary logistic regression analysis.

| Variables (N: 498) | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Class (1st–2nd grade) | 0.382 | 0.179 | 0.813 | .013 |

| Family income perception (low) | 0.411 | 0.172 | 0.985 | .046 |

| Previous vaccination rejection | 0.291 | 0.153 | 0.555 | <.001 |

| COVID-19 positive family members | 1.009 | 0.555 | 1.836 | .975 |

| COVID-19 information source MoH and WHO | 1.629 | 0.913 | 2.908 | .099 |

| Relying on the explanations of health professionals | 0.899 | 0.537 | 1.507 | .686 |

| Attitudes and concerns about the vaccine | ||||

| Lack of information on vaccination | 0.738 | 0.414 | 1.315 | .303 |

| Vaccine is safe | 6.014 | 2.898 | 12.480 | <.001 |

| The vaccine is effective | 2.138 | 1.053 | 4.342 | .035 |

| The vaccine has side effects | 0.552 | 0.309 | 0.985 | .044 |

| Perceiving himself as a guinea pig in vaccination | 0.436 | 0.246 | 0.773 | .004 |

| Worried that the vaccine will cause a Covid-19 infection | 1.163 | 0.475 | 2.845 | .741 |

| Thinking that the vaccine will change the genetic structure | 0.322 | 0.131 | 0.795 | .014 |

| Those who prefer to be infected with COVID-19 rather than being vaccinated | 0.708 | 0.277 | 1.815 | .473 |

| Constant | 5.255 | .007 | ||

SE=0.094, Wald=40.430, P=.000, R2=0.520.

SE: Standard errors, CI: Confidence Interval, OR: Odds ratios, R2: Nagelkerke R Square.

HCPs are considered the most reliable source of information on vaccines, and their recommendations play a major role in patients' vaccination decisions. Hence, vaccine acceptance by HCPs would increase vaccine uptake by the public. Frontline HCPs, including nurses, are susceptible to acquiring the virus due to a variety of factors, including exposure, inadequate supply of personal protective equipment, and inadequate infection control. Therefore, being vaccinated will not only protect them and their families but will also allow them to advise their communities to get vaccinated against COVID-19. A universal vaccination program is an crucial measure to control the pandemic and achieve herd immunity. Vaccine hesitancy is a limiting step in global attempts to control the pandemic with adverse health and socioeconomic consequences.9,10,19

The current study revealed that two-thirds (64.5%) of the nursing students were willing to get the vaccine. Our findings are consistent with the intention of the nurses working in our country to be vaccinated.11 While the willingness of the students to be vaccinated against COVID-19 was low in the United States and across 7 European countries (45%; 44%, respectively),3,13 it was higher among Chinese students (83.3%).20 In other studies, conducted on medical students revealed that 73% intended to be vaccinated in the USA,21 whereas 35% in Egypt.9 A rapid systematic review of 13 studies assessing the attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination among the HCPs concluded that vaccine acceptance varied widely and ranging from 27.7% to 77.3%.19 However, these studies also revealed differences in the intention to be vaccinated between nursing students and HCPs. Our study also showed that younger students and those with milder viral exposure are more likely not to accept the vaccine compared to older students. Differences between various studies can be attributed to the sample difference, data collection time, morbidity and mortality rate in countries, vaccine information sources, types of approved vaccines between countries, and rapid and changing flow of country-specific information about the disease or vaccines.9,11,13,15

Our findings also indicated that their willingness to receive the vaccine was not without concerns and/or hesitation. The current study revealed that the students' attitudes and concerns on COVID-19 vaccine mostly included the inadequacy of vaccine information, its side effects, effectiveness, and safety, the thought that they were used as experiments for COVID-19 vaccine application, and the thought of preferring natural immunity rather than being vaccinated. Several studies assessing attitudes and concerns toward the COVID-19 vaccine revealed that participants commonly expressed their concerns toward the vaccine effectiveness and side effects, insufficient vaccine information, distrust of the supplied vaccine and the supplier company, negative effects of the media, thoughts that there should be no vaccine according to their sources, thoughts that the COVID-19 vaccine will infect the virus or change their genetic structure, and thought that they are used as experiments in the COVID-19 vaccine application.7,9,13,15,22 These expressed concerns about vaccine efficacy are not surprising, as vaccine development can take 10–15 years.11 However, other concerns, such as the vaccine will alter their genetic structure, the vaccine will infect them with the virus, and perception of being used as experiments in the COVID-19 vaccine application, arise. Vaccine misinformation and insufficient advanced vaccine information can increase anxiety and lead to an overestimation of potential side effects. Many hesitant individuals are anticipated to accept the vaccine if they were reassured on vaccine safety and effectiveness and if reliable information is provided.21

University students and HCPs use various resources through social media and personal networks to acquire COVID-19 infection and vaccine information.19 A study conducted among medical and health students revealed that social media was used as an important source of information about the virus.23 Another study involving students from a large public university in New Jersey stated that the most reliable sources of COVID-19 vaccine information were official health institutions (78.1%) and medical professionals (63.2%), respectively.24 In the current study, official health institutions (WHO and Turkey MoH) were reported to be the primary sources of information among the students, whereas social media (72.7%) came second. Vaccine concerns and hesitancy are heightened by social media, conspiracy theories, and misinformation.9,11 The WHO has characterized the spread of misleading and false information as an infodemia, which needs to be addressed.23 In order to address the lack of information and misinformation surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine, it is necessary to include training on this subject in the curriculum.

The current study revealed that the most common reasons for not wanting to be vaccinated were distrust in vaccine effectiveness due to the mutation of the virus, vaccines side effects, distrust of the current vaccine and the company, and the negative effects of news in the media. Similar results were obtained in previously conducted studies, wherein most of the reasons for the unwillingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 include constantly mutating severe acute respiratory syndrome COVID-19, vaccine ineffectiveness, serious long-term side effects, insufficient vaccine information, rapid vaccine production, preference for natural immunity, the thought that COVID-19 vaccines would change the DNA structure, fear that the vaccines would cause infertility, fear of high financial costs if the vaccine is not free, and media misrepresentation of the vaccine.9,10,13,21

Factors associated with the intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19The willingness to be vaccinated does not depend on just 1 factor. It can be affected by the individuals' social, cultural, and economic structures, age, gender, information from HCPs, individual or familial COVID-19 infection experiences, chronic diseases, general attitudes and beliefs toward vaccines, previous experiences of vaccine rejection, and traditional social messages.11,15 The current study revealed a low COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among students who were in lower classes, with low family income perception, and with previous vaccine rejection experience. Similar studies that were conducted among HCPs revealed high acceptance rates among the male gender, increasing age, education, and income level.15,19,25,26

Some studies revealed a relationship between prior seasonal influenza vaccination and intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19.13,17,18,24,26 The current study revealed no correlation between the influenza vaccination of nursing students in the last 2 years (8.8%) and the intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19. However, previous vaccine rejection experience, either by the individual or a relative (17.1%), negatively affected one's intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Individual or familial experiences of vaccine rejection is an obstacle to acquiring herd immunity through vaccination, and many countries have reported an increased incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases in recent years.18 This may cause very serious consequences worldwide as it threatens all historical achievements in reducing the burden of infectious diseases that have been affecting humanity for centuries.7

Some research suggests that vaccination acceptance is also affected by other motivational and psychological factors, such as anxiety, experiences, and disease risk perception.3,27 Many of the nursing students in the study perceived COVID-19 infection as a serious problem that would continue for a long time and two-thirds of them believed their risk of contracting infection, although the rate of individual infection is low (8.2%), whereas the rate of infection and death in the family and close environment is detected as higher. Additionally, the pandemic process has negatively affected the lives of students. An increased intention to be vaccinated was observed in students whose family members had COVID-19 infection, but no difference was observed in other factors. Nursing students in Europe also perceived contracting COVID-19 infection as a serious problem at similar rates,13 whereas a study among medical students in Egypt confirmed that 4.4% had had an infection and 51.5% in their immediate social environment had contacted the virus.19 Among the COVID-19 vaccination motivations, the fear of being infected or the fear of infecting the family and the history of chronic disease increased the tendency to be vaccinated.9,13,19,25,26,28 The study of revealed that13 the pandemic process adversely affected the mental health of nursing students and increased their depression and anxiety levels.

The current study observed that students whose primary sources of COVID-19 information were official institutions (WHO and MoH) and those who relied on the statements of HCPs had an increased intention to be vaccinated. People who rely on government sources, doctors, and public health experts' explanations about COVID-19 information were more likely to accept the vaccine.13,19,21,25,29 Obtaining information from unreliable sources and social media increased students' suspicions about vaccines. The presence of the anti-vaccine movement, especially on social media, may have contributed to the unwillingness to be vaccinated.15,30 The regression analysis revealed that nursing students' intention to be vaccinated was positively affected by vaccine effectiveness and safety, among the attitude that concerns the vaccine and its side effects, whereas seeing oneself as an experiment in the vaccine administration and the thought that the vaccine will change the genetic structure were negative factors. The study conducted with Palestinian nurses revealed that the factors that prevent the intention to be vaccinated included preference of natural immunity, fear of long-term vaccine complications, insufficient vaccine information, fear of the vaccine, and the misrepresentation of the media about the vaccine.22 Vaccine efficacy and safety, insufficient knowledge about the vaccine, and fear of long-term side effects are consistent with studies of Saied et al, Kwok et al, and Wang et al.9,10,31 Students may have negative cognition in vaccination. That's why, schools should strengthen education on adverse reactions of COVID-19 vaccine, not only from knowledge, but also from psychological and physiological, so that students can eliminate fear and enhance the willingness to vaccinate.

LimitationsThe study was conducted for exploratory purposes, with the aim of ensuring the participation of as many students as possible. Therefore, a power analysis was not performed. The study took place approximately 1–2 months after the vaccine was released, which may reflect the students' eagerness to receive their first vaccine dose. It is important to note that the intention to be vaccinated does not necessarily translate into actual vaccination behavior. Consequently, it may not directly predict future vaccination behavior. Prospective studies can be conducted to analyze the differences between actual vaccination behavior and pre-vaccination intentions. These research findings do not represent the entirety of nursing students in the country, but they can provide insights for vaccination programs.

ConclusionOne-third of nursing students do not intend to be vaccinated. Concerns and barriers related to the vaccine included lack of information, safety, efficacy, and side effects, as well as false beliefs that the vaccine will transmit viruses and they are used as experiments. HCPs can encourage individuals to receive vaccines. Nursing students are known to be the future HCPs and will play a decisive role in counseling individuals in the community about the risks of COVID-19 and the benefits of the vaccine; therefore, focusing on training that is aimed at increasing the knowledge about vaccines, eliminating their negative attitudes and concerns, and building confidence in vaccines is necessary. Nursing students should be encouraged to read scientific research to eliminate misinformation through social media. Using and following reliable news sources can build trust in vaccines.

Ethical ConsiderationsEthical permission to carry out the research was obtained from Ege University Health Sciences Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee (Approval number: 2021/982). Written informed consent was obtained from all students who participated in the study.

Funding sourcesNone.

Author contributionsStudy design, Conceptualization, Methodology: ZD; MKW, Data collection: ZD; MKW; Data analysis and interpretation: ZD; Writing- reviewing and editing: ZD; MKW.

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to all the nursing students who participated in the research. We would also like to extend our sincere appreciation to the Ege University Planning and Monitoring Coordination of Organizational Development and Directorate of Library and Documentation.