The objective of this study is to determine the perceptions of the auditors and teachers in relation to the issue of independence in auditing. We used appropriate statistic instruments and gathered the opinions of a sample of 1275 questionnaires given to these professionals, which obtained an answer rate of 35% and correspond to 447 questionnaires fully answered. The results allow us to conclude that there are particular specificities, not very efficient control structures, profound differences regarding this concept depending on the group under study, and a set of similarities with the international research. The research is innovative, nationally and internationally, due to the richness given by the diversity of the perceptions. As for the contributions, we enhance that this is the first study with an empirical basis ever done in Portugal and that it allows us to alert the professional orders and institutions to improve the safeguard of independence mechanisms.

The perception of the different types of auditors regarding the aim of the study, as far as we know, has not been studied before and nor have auditing teachers of higher education, who have a fundamental role in teaching, been sounded. The various international studies on this theme have mainly analysed the following aspects: nomination and selection, experience of the experts who take part in the supervision and audit, corporate governance structures, independence, importance of the clients in the income structure, sanction mechanisms and auditors’ integrity and competence. The sounding of the professionals themselves has not yet been studies.

Thus, the general objective of the research is to analyse the independence of the auditors in Portugal, and how it is perceived by the professional connected with auditing and teaching. In more specific terms, the study intends to find out if, regarding independence, there are significant differences in the way that each professional group faces the auditors’ behaviour in relation to independence, the control mechanisms of this attribute, and if the Portuguese auditing market promotes independence.

For this purpose we have established three hypotheses:

H1: there are no statistically significant differences in the way each professional group faces the auditors’ behaviour regarding independence.

H2: there are no statistically significant differences in the way each professional group faces the implementation of control structures.

H3: the perception of each professional group regarding the auditing market does not present statistically significant differences.

The procedure used to reach the general and specific objectives mentioned above and test the hypotheses previously defined, was creating questionnaires, which were published and received in 2010, for the auditors group (statutory auditors – ROC's, internal auditors – AI's, court auditors – ATC's) and teachers (Prof's). All the subgroups were consulted in their university, where 1275 questionnaires were sent and 521 were received, 447 of which were fully answered. We obtained therefore a response rate of 35%.

The classic and modern authors of auditing (Porter, Simon, & Hatherly, 2008, pp. 101–159; Puttick, Van Esch, & Kana, 2007, p. 142) deem independence to be a necessary albeit insufficient condition. Hence, the meaning of the term in auditing is somewhat controversial, given the existence of a number of factors that lead the public to doubt the independence of auditors: relations with the audited company and the actual organisation of the profession itself (Intosai GOV 9140, 2009, pp. 1–8; Stewart & Subramanian, 2009, pp. 3–26; Wright & Capps, 2012, pp. 63–79).

Independence, as a multidimensional concept, is connected to the provision of extra auditing services together with auditing services, a state of affairs known as joint economic production, and which has a negative impact on the perception of objectivity and independence in the profession. It is further related to the issue of auditor rotation (Bamber & Venkataraman, 2007, p. 1), with there being, in fact, legal frameworks in some countries–Italy, Portugal (Companies of public interest), United States (authors’ rotation and not from auditing companies), for example – which advocate the rotation of auditors after a certain period of a mandate. This is a mechanism, according to regulating agencies, which has a positive effect on independence (SOX, 2002).

Therefore, this study can be differentiated from other research because:

- –

Generally speaking, and to the best of our knowledge, research on independence in auditing has largely focused on external auditors, which constitutes an excessively reductionist perspective.

Thus, the sounding of court auditors, internal auditors and teachers constitute an innovative aspect, as they offer different perspectives on the theme. In addition, it is the first study with an empirical basis ever done in Portugal.

Having outlined the central theme, the second part discusses the most relevant research related to this. The third presents the statistical methodology which aims to quantify the understanding of the different professionals involved in its practice and teaching, regarding three distinct areas: behaviour of auditors, control structures and the auditing market, which cover all the criteria used to explain the concept of independence. In the fourth section, the results are discussed, and, in the fifth and final part, we draw up conclusions, refer to the limitations of the study and put forward suggestions for future research.

2Review of literatureThe issue of the erosion of independence has been analysed at various levels: nomination and selection of the auditors, analysis of the various individuals who are part of the auditing or supervisory committees, the influence of the corporate governance structures, the importance of the client in the profit structure of the auditing company, the provision of services other than auditing, the sanction mechanisms, and the auditor's integrity and competence.

Therefore, when analysing the management acts of companies, Martinov-Bennie, Cohen and Simnett (2011, pp. 656–671), Carcello, Neal, Palmrose and Shohz (2011, pp. 396–430), Cohen, Gaynor, Krishnamoorthy and Wright (2011, pp. 129–147), Chu, Du and Jiang, (2011, pp. 135–153) concluded that company bodies have an important role in the selection, nomination and evaluation of auditors, as well as in their recruitment to work in companies they have previously audited. They also suggest that the nomination of individuals who are part of auditing or supervision committees is influenced by the members of the management body, thereby concluding that the corporate governance structures are decisive in the pragmatic operationalisation of the concept of independence (Guo & Yeh, 2014, pp. 96–104; Karaibrahimoglu, 2013, pp. 273–284).

In their turn, Li (2009, pp. 201–330) studied the importance of clients and their relationship with the auditors’ independence and suggest that there is a correlation between the global fees received by the company and its total income, which affects the auditor's opinion in relation to the company's continuity. Machado de Almeida, (2012, pp. 12–54), Benau (1998, pp. 158–167) analysed the concentration of the auditing market in Portugal and Spain and concluded that the situation promoted potential impairments in the auditing information Furthermore, Karasu (2014, pp. 79–105), Chan and Wu (2011, pp. 176–211), and Quick and Rasmussen (2009, pp. 163–183)suggest that any consultancy provided to the audited companies can put the auditors in a position of impairment, in terms of independence, criticising, therefore, the joint supply services. By following this line of thought, the CPAB (2012, pp. 60–69)1 and the PCAOB (2006)2 drastically restricted situations of consultancy (Brandon, Crabtree, & Maher, 2004, pp. 89–103; Deloitte, 2008, pp. 1–8).

The environment in which the auditors operate has also been studied (Glazer and Jaenicke, 2002, pp. 329–352; Ryan et al., 2001, pp. 373–386) and the results point to an effective perception, on the part of the auditor, that the existence of sanction mechanisms is a decisive incentive for the auditors to maintain their independence, together with the risk of litigation and revision of their work by peers.

Generally, the aforementioned researchers are receptive to an approach based on the implementation of rules in relation to this issue – rules based – to the detriment of an approach through principles–principles based. However, Taylor, DeZoort, Munn and Thomas (2003, pp. 257–266) and Johnstone and Bedard (2001, pp. 1–18) prefer a more conceptual approach based on the paradigm of the theory of trust, where independence is related to the auditor's integrity and competence.

In legal terms, independence is also considered an essential factor. Consequently, SOX (2002) and SEC (2003), Yu (2011, pp. 377–441) recommend the reinforcement of the auditor's independence mechanisms, and the various ethical and professional deontology codes (AICPA, IFAC) approach this issue in an analytic way, forming a set of rules that establish the threats and the safeguards, in a context clearly influenced by Anglo-Saxon surroundings. Finally, Hudaib and Haniffa (2009, pp. 237) contextualise the concept and refer to its contingent character, and relate it to an important set of cultural dimensions, highlighting that the concept is owned by a very restricted group of society that, because of their important social role, interpret the concept in an opportunist way.

3MethodologyWe intend to analyse the perceptions of different inquired professional groups regarding the ethical behaviour of auditors, if they show independence, if there are mechanisms controlling the actions and technical and professional performances, and if that activity, at a market level – offer and demand – promotes the attribute under study. To do so, we used Kruskal–Wallis's non parametric test because it is the adequate technique to evaluate if there are any significant differences in the answers in relation to each professional group. Normally, a variance analysis would be used (ANOVA oneway) but it depends on the hypothesis that all the populations involved are independent and normally distributed. Kruskal–Wallis’ test does not entail any restriction on the comparison. Kruskal–Wallis’ test is an extension to Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney's test, which uses three or more populations to compare. It tests the null hypothesis that all populations have equal distribution functions against the alternative hypothesis that at least two populations have different distributions. We also used the Dunn method, in case the null hypothesis is rejected, to determine which groups are responsible for the rejection of H0.

3.1Sample and data collectionQuestionnaires were drawn, handed in and received in 2010; they were sent to the professional technicians described above and to the teachers (Prof's).

The reasons for selecting these professional classes are the following: the ROC's because they certify the financial statements of the companies; the AI's due to their role in the prevention and detection of susceptible frauds in the companies; the ATC's because they audit public entities and teachers due to their important role in the training of auditors.

Various terms were presented in relation to the issue under study to which each group agreed or disagreed. This questionnaire was sent to all auditors and teachers.

We used the technique of the questionnaires constituted by a set of terms or statements because it is an instrument that allows us to evaluate attitudes and opinions (Vaz Freixo, 2011, pp. 197–211). It also allows us to confirm or reject the various hypotheses under study. In terms of implementation, we did a pre test to a reduced sample of the population to avoid interpretation doubts.

From the 1275 questionnaires sent to the target population, we received 521, 447 of which were fully answered, and only these were studied. The answer rate (TR) is around 35%, and is interpreted as an index for measuring the care with which the study was carried out and the interest or relevance that the study has on company management (Frohlich, 2002). The TR is acceptable, as it is above the minimum recommended by the Malhotra and Grover's (1998) method, which is 23%.

When collecting the information, we gave importance to its presentation and the promptitude; these factors were considered determining to obtain a greater TR (Frohlich, 2002; Yammarino, Skinner, & Childers, 1991). Taking into consideration the existing different levels of knowledge, we considered that the conception of two distinctive classes for enquiry was justified: the auditing professionals and the teachers.

In both questionnaires, the first bloc is in general terms and tries to recognise certain factual characteristics of the inquired. The second bloc is divided in 11 statements aiming at detecting perceptions, attitudes and behaviours which synthesise the various aspects related to the issue under study.

They were asked questions concerning the behaviour of auditors, the control structure and the auditing market. Each set of questions contains information to which the respondents answer according to a Likert scale where 1 corresponds to “strongly disagree” and 5 corresponds to “strongly agree”. The questionnaire – the questions of which are presented in the Table 1 – was sent to all the auditors and teachers.

Questions.

| Auditor's behaviour | |

| 1.1 | Action totally independent in relation to company |

| 1.2 | Lack of training to detect errors and fraud |

| 1.3 | No auditor rotation |

| 1.4 | Insufficient planning of audits |

| 1.5 | Unethical performance of auditors |

| 1.6 | Lack of technical ability of auditors |

| Control structures | |

| 2.1 | Poor performance on the part of control or supervisory bodies |

| 2.2 | Absence of or insufficient control |

| Auditing market | |

| 3.1 | Fees insufficient to extend the scope and reach of auditing |

| 3.2 | Existence of many self-employed auditors |

| 3.3 | Reduced size, in general, of the majority of auditing companies |

The types of questions aim to cover the seven criteria of independence (C) established by AICPA3 and SEC,4 that is:

C1: State of spirit: integrity, objectivity, character, honesty and courage.

C2: Relationship with the clients: transactions with the clients, gifts received from clients, frequent lunches with clients, commissions received from clients, etc.

C3: Propriety, employment and other interests: direct and indirect patrimonial interests in the clients’ companies, possibilities of employment in the audited companies for the staff and family.

C4: Conflict with the clients: litigation between auditors and their clients, unpaid fees.

C5: Partners and staff rotation.

C6: Provision of non-auditing services: accounting services, tax consultancy, management consultancy and other services.

C7: Fees.

The criteria of independence referred to are embedded in questions 1.1, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3. Other criteria were added related to a conceptual structure with two additional elements to control the subjectivity of the auditors’ decisions: ethics and professional expertise (experience or competence).

Thus, questions 1.2, 1.4, 1.5 and 1.6 respond to the ethical performance and to the expertise/experience according to the criteria:

C8: Experience: to detect errors and frauds, insufficient planning of audits, and technical inability of auditors.

C9: Unethical performance of auditors.

In turn, questions 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3, refer to the market variable and aim to determine whether the auditors and the teachers relate it to independence.

C10: The proliferation of the supply of individual self-employed auditors.

C11: Reduced size, in general, of the majority of auditing companies.

Table 2 presents the questions related to the various variables constituting the problem.

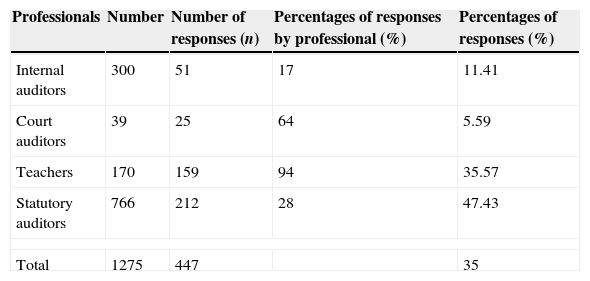

The number of questionnaires sent and received for each of the groups was as shown in Table 3:

Number of responses per professional group.

| Professionals | Number | Number of responses (n) | Percentages of responses by professional (%) | Percentages of responses (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal auditors | 300 | 51 | 17 | 11.41 |

| Court auditors | 39 | 25 | 64 | 5.59 |

| Teachers | 170 | 159 | 94 | 35.57 |

| Statutory auditors | 766 | 212 | 28 | 47.43 |

| Total | 1275 | 447 | 35 | |

The sample collected is constituted by 447 professionals, 51 (11.41%) of whom are internal auditors, 25 (5.59%) are court Auditors, 159 (35.57%) are teachers and the rest, 212 (47.43%), are statutory auditors. These results are presented in the following table.

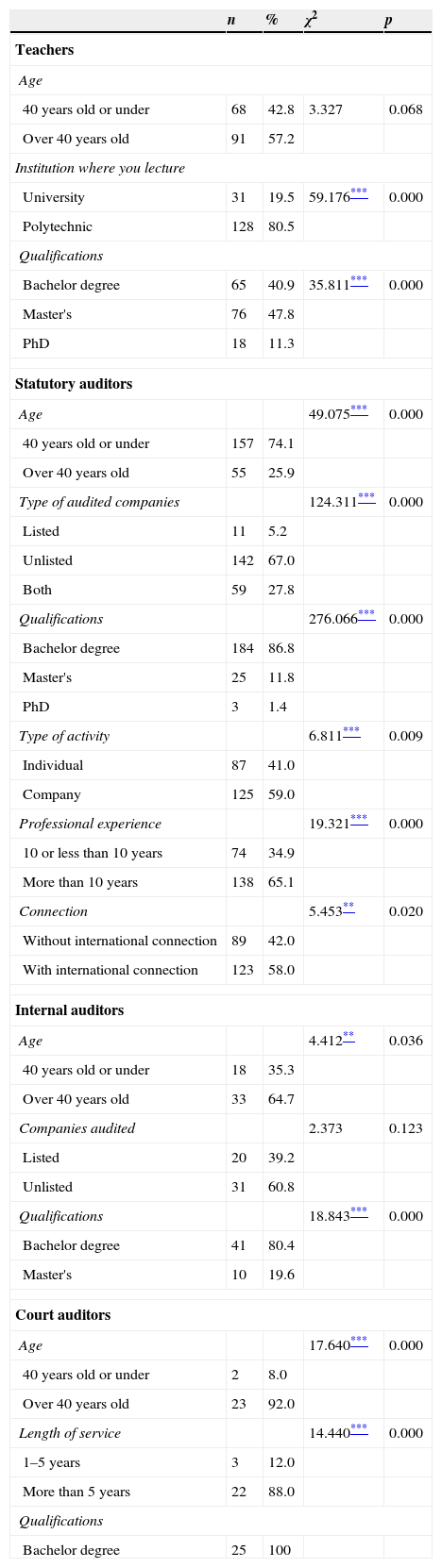

The characterisation of each of the professional groups that participated in this study is presented in Table 4.

Description of the sample.

| n | % | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teachers | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 40 years old or under | 68 | 42.8 | 3.327 | 0.068 |

| Over 40 years old | 91 | 57.2 | ||

| Institution where you lecture | ||||

| University | 31 | 19.5 | 59.176*** | 0.000 |

| Polytechnic | 128 | 80.5 | ||

| Qualifications | ||||

| Bachelor degree | 65 | 40.9 | 35.811*** | 0.000 |

| Master's | 76 | 47.8 | ||

| PhD | 18 | 11.3 | ||

| Statutory auditors | ||||

| Age | 49.075*** | 0.000 | ||

| 40 years old or under | 157 | 74.1 | ||

| Over 40 years old | 55 | 25.9 | ||

| Type of audited companies | 124.311*** | 0.000 | ||

| Listed | 11 | 5.2 | ||

| Unlisted | 142 | 67.0 | ||

| Both | 59 | 27.8 | ||

| Qualifications | 276.066*** | 0.000 | ||

| Bachelor degree | 184 | 86.8 | ||

| Master's | 25 | 11.8 | ||

| PhD | 3 | 1.4 | ||

| Type of activity | 6.811*** | 0.009 | ||

| Individual | 87 | 41.0 | ||

| Company | 125 | 59.0 | ||

| Professional experience | 19.321*** | 0.000 | ||

| 10 or less than 10 years | 74 | 34.9 | ||

| More than 10 years | 138 | 65.1 | ||

| Connection | 5.453** | 0.020 | ||

| Without international connection | 89 | 42.0 | ||

| With international connection | 123 | 58.0 | ||

| Internal auditors | ||||

| Age | 4.412** | 0.036 | ||

| 40 years old or under | 18 | 35.3 | ||

| Over 40 years old | 33 | 64.7 | ||

| Companies audited | 2.373 | 0.123 | ||

| Listed | 20 | 39.2 | ||

| Unlisted | 31 | 60.8 | ||

| Qualifications | 18.843*** | 0.000 | ||

| Bachelor degree | 41 | 80.4 | ||

| Master's | 10 | 19.6 | ||

| Court auditors | ||||

| Age | 17.640*** | 0.000 | ||

| 40 years old or under | 2 | 8.0 | ||

| Over 40 years old | 23 | 92.0 | ||

| Length of service | 14.440*** | 0.000 | ||

| 1–5 years | 3 | 12.0 | ||

| More than 5 years | 22 | 88.0 | ||

| Qualifications | ||||

| Bachelor degree | 25 | 100 | ||

The statistics were determined on the basis of adherence to χ2 adherence tests.

The analysis of the previous table enhances that there are statistically significant differences regarding the qualification, age, international connections, experience, etc., in the different groups under study, whose intensity is susceptible of being measured by Spearman statistic analysis but that we do not consider a priority in our study.

3.2Statistical analysisThe answers to the questions obtained were collected, and then the descriptive statistics (relative and absolute frequencies) were determined, giving the results presented below. We applied the Kruskal–Wallis’ non-parametric test, as it is a suitable technique to test the possible existing significant differences in the answers in relation to each of the professional groups.

3.3HypothesesIn accordance with the subject under study, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): There are no significant differences in the way each professional group (statutory auditors, court auditors, internal auditors, and teachers) view the auditors’ behaviour in respect to independence. This hypothesis is based on Rahmina and Agoes (2014, pp. 324–331), Taylor et al. (2003), McMillan (2004), and Johnstone and Bedard (2001) researches.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): There are no statistically significant differences in the way each professional group (statutory auditors, court auditors, internal auditors, and teachers) view the action of the control structures. This hypothesis is founded on Guo and Yeh (2014, pp. 96–104), Karasu (2014, pp. 79–105), Chan, Liu and Sun (2013, pp. 1129–1147), Karaibrahimoglu (2013, pp. 273–284), Chu et al. (2011), Martinov-Bennie et al. (2011), Cohen et al. (2011), Carcello et al. (2011) studies.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The perception of each professional group (statutory auditors, court auditors, internal auditors, and teachers), in relation to the auditing market, does not present statistically significant differences. This hypothesis is structured according to the work of Chan and Wu (2011), Li (2009) and Porter et al. (2008).

For the purpose of this study, the answers to the questionnaires were put into two sets, which correspond to “agree” and “disagree”, to calculate the corresponding frequencies for “agree” we considered the answers “4” and “5”, while for “disagree” we considered the answers “1” and “2”. The difference in the percentage in relation to these two cases, in each question, corresponds to the situations where the answer is “neither agree nor disagree”.

Subsequently, we used non-parametric statistics by implementing the Kruskal–Wallis test, whose results are presented below.

Regarding the questions related to the auditors’ behaviour, for the group of teachers, it is question 1.3, “No auditor rotation”, with which this professional group most agree (76.1%; M=3.54; DP=1.036). It is also this question that obtained the highest level of agreement among the internal auditors (70.6%; M=3.49; DP=1.120).

The statutory auditors and the court auditors’ point of view regarding this question is similar. The question 1.1, “Action totally independent in relation to company”, obtained the most agreement in both groups. Thus, the agreement percentage for the statutory auditors is 67.0% (M=3.35; DP=1.085), and the percentage for the court auditors is 80.0% (M=3.84; DP=41.2).

Regarding the set of questions concerning the control structure, it was question 2.2, “Lack of or insufficient control” that the teachers (83.0%; M=3.74; DP=0.896) and the statutory auditors (81.6%; M=3.65; DP=0.944) most agreed with. It is worth noting that the percentage of agreement with this question for the court auditors is also high (80.0%; M=3.72; DP=1.061) although it was question 2.1 “Weak action from the control and supervision bodies” which this group most agreed with (84.0%; M=3.92; DP=0.954). This was also the question which obtained the highest level of agreement from the internal auditors (66.7%; M=3.29; DP=1.238).

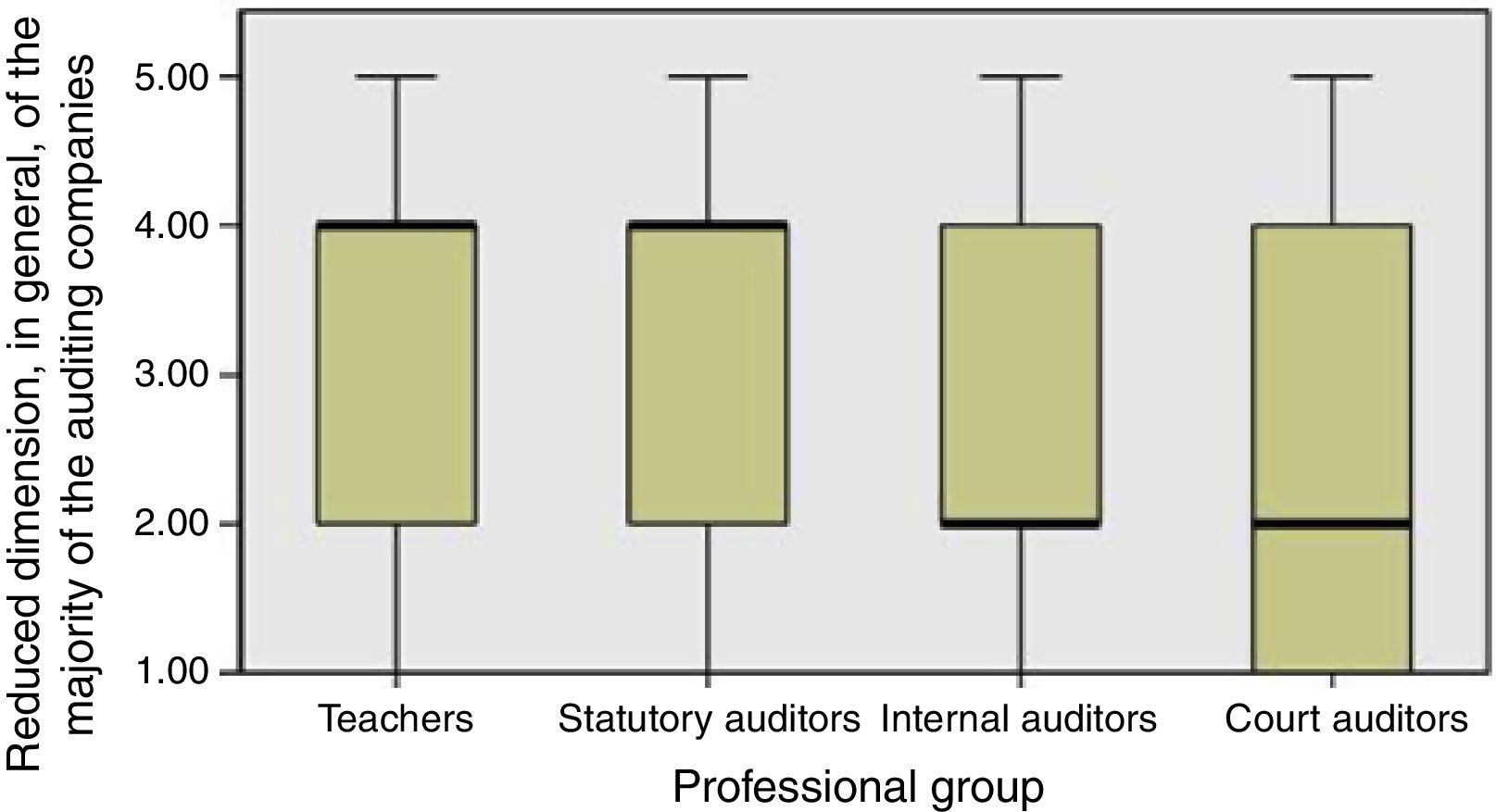

Finally considering the questions concerning the auditing market, it can be seen that the question with which the teachers most agree is 3.3 “Reduced dimension, in general, of the majority of the auditing companies” (62.9%; M=3.27; DP=1.129). However, the question 3.1, “Insufficient fees to widen the scope and the reach of auditing”, obtained the highest level of agreement on the part of the statutory auditors and internal auditors. Thus, for the statutory auditors, this question obtained 85.8% of agreement (M=3.76; DP=0.799) and 58.0% (M=3.24; DP=1.274) from the internal auditors.

In relation to the court auditors, the answers to questions 3.1 “Insufficient fees to widen the scope and the reach of auditing” and 3.2 “A lot of auditors/supervisors are self-employed”, stand out against question 3.3, “Reduced dimension, in general, of the majority of the auditing companies”. Thus, the percentage of agreement to question 3.1 for this professional group is 40.0% (M=2.60; DP=1.414) and also 40.0% of the statutory auditors (M=2.80; DP=1.414) agree with the statement 3.2.

The results are presented in Table 5.

Descriptive statistics per subgroups of participants.

| Teachersn=159 | Statutory auditorsn=212 | Court auditorsn=25 | Internal auditorsn=51 | Kruskal–Wallis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree (disagree) % | Mean (DP) | Agree (disagree) % | Mean (DP) | Agree (disagree) % | Mean (DP) | Agree (disagree) % | Mean (DP) | χ2 | p-Value | |

| Auditors’ behaviour | ||||||||||

| Question 1.1 | 42.1 (57.9) | 2.81 (1.154) | 67.0 (33.0) | 3.35 (1.085) | 80.0 (20.0) | 3.84 (1.143) | 41.2 (58.8) | 2.78 (1.346) | 31.968*** | 0.000 |

| Question 1.2 | 56.0 (44.0) | 2.90 (1.197) | 32.1 (67.9) | 2.61 (1.080) | 48.0 (52.0) | 3.08 (1.470) | 64.7 (35.3) | 3.27 (1.266) | 13.875*** | 0.003 |

| Question 1.3 | 76.1 (23.9) | 3.54 (1.036) | 59.9 (40.1) | 3.25 (1.119) | 48.0 (52.0) | 3.00 (1.384) | 70.6 (29.4) | 3.49 (1.120) | 7.972** | 0.047 |

| Question 1.4 | 52.8 (47.2) | 3.06 (1.239) | 51.4 (48.6) | 3.06 (1.083) | 20.0 (80.0) | 2.32 (1.030) | 9.8 (90.2) | 2.12 (0.765) | 36.248*** | 0.000 |

| Question 1.5 | 30.2 (69.8) | 2.58 (1.093) | 30.2 (69.8) | 2.54 (1.050) | 4.0 (96.0) | 1.76 (0.663) | 7.8 (92.2) | 2.02 (0.678) | 26.053*** | 0.000 |

| Question 1.6 | 13.2 (86.8) | 2.20 (0.926) | 12.3 (87.7) | 2.20 (0.819) | 12.0 (88.0) | 2.08 (0.812) | 17.6 (82.4) | 2.16 (0.946) | 1.414 | 0.702 |

| Control structure | ||||||||||

| Question 2.1 | 74.8 (25.2) | 3.56 (1.106) | 55.7 (44.3) | 3.14 (1.194) | 84.0 (16.0) | 3.92 (0.954) | 66.7 (33.3) | 3.29 (1.238) | 18.233*** | 0.000 |

| Question 2.2 | 83.0 (17.0) | 3.74 (0.896) | 81.6 (18.4) | 3.65 (0.944) | 80.0 (20.0) | 3.72 (1.061) | 35.3 (64.7) | 2.65 (1.383) | 32.436*** | 0.000 |

| Auditing market | ||||||||||

| Question 3.1 | 37.1 (62.9) | 2.67 (1.204) | 85.8 (14.2) | 3.76 (0.799) | 40.0 (60.0) | 2.60 (1.414) | 58.8 (41.2) | 3.24 (1.274) | 78.891*** | 0.000 |

| Question 3.2 | 51.6 (48.4) | 3.05 (1.168) | 44.3 (55.7) | 2.45 (1.490) | 40.0 (60.0) | 2.80 (1.414) | 33.3 (66.7) | 2.63 (1.166) | 26.974*** | 0.000 |

| Question 3.3 | 62.9 (37.1) | 3.27 (1.129) | 59.9 (40.1) | 3.21 (1.056) | 28.0 (72.0) | 2.32 (1.345) | 41.2 (58.8) | 2.75 (1.197) | 20.647*** | 0.000 |

The mean of the groups was determined based on the Likert scale from 1 to 5 points, where 1 corresponds to “Disagree totally” and 5 corresponds to “Agree totally”.

From the analysis of the previous answers, we notice that there are statistically significant differences between the answers to each one of the questions related to the professional group in 10 of the 11 questions.

To identify in which professional groups the answers to each question are significantly different from the others, we undertook a multiple comparison of the means by using Dunn statistics.

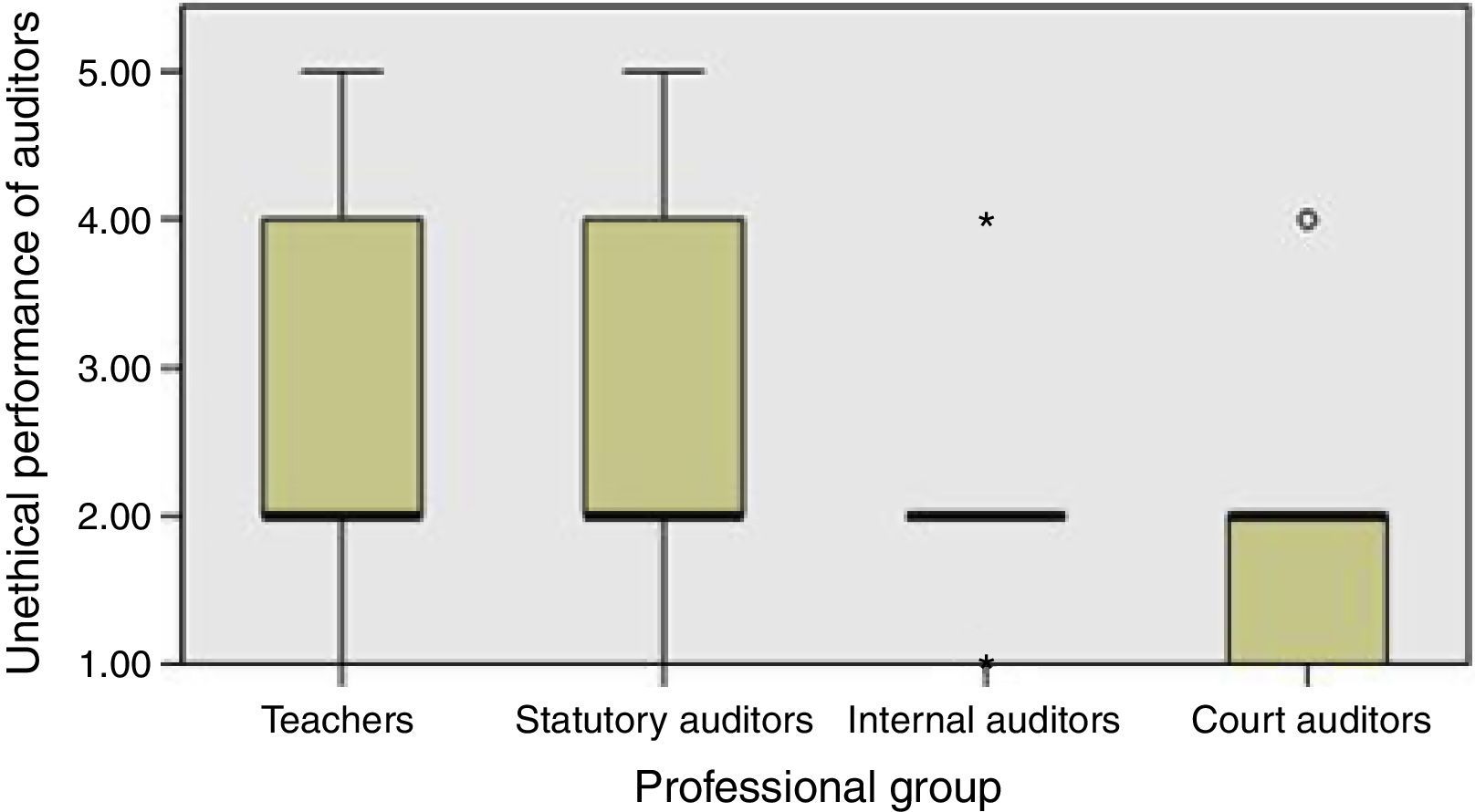

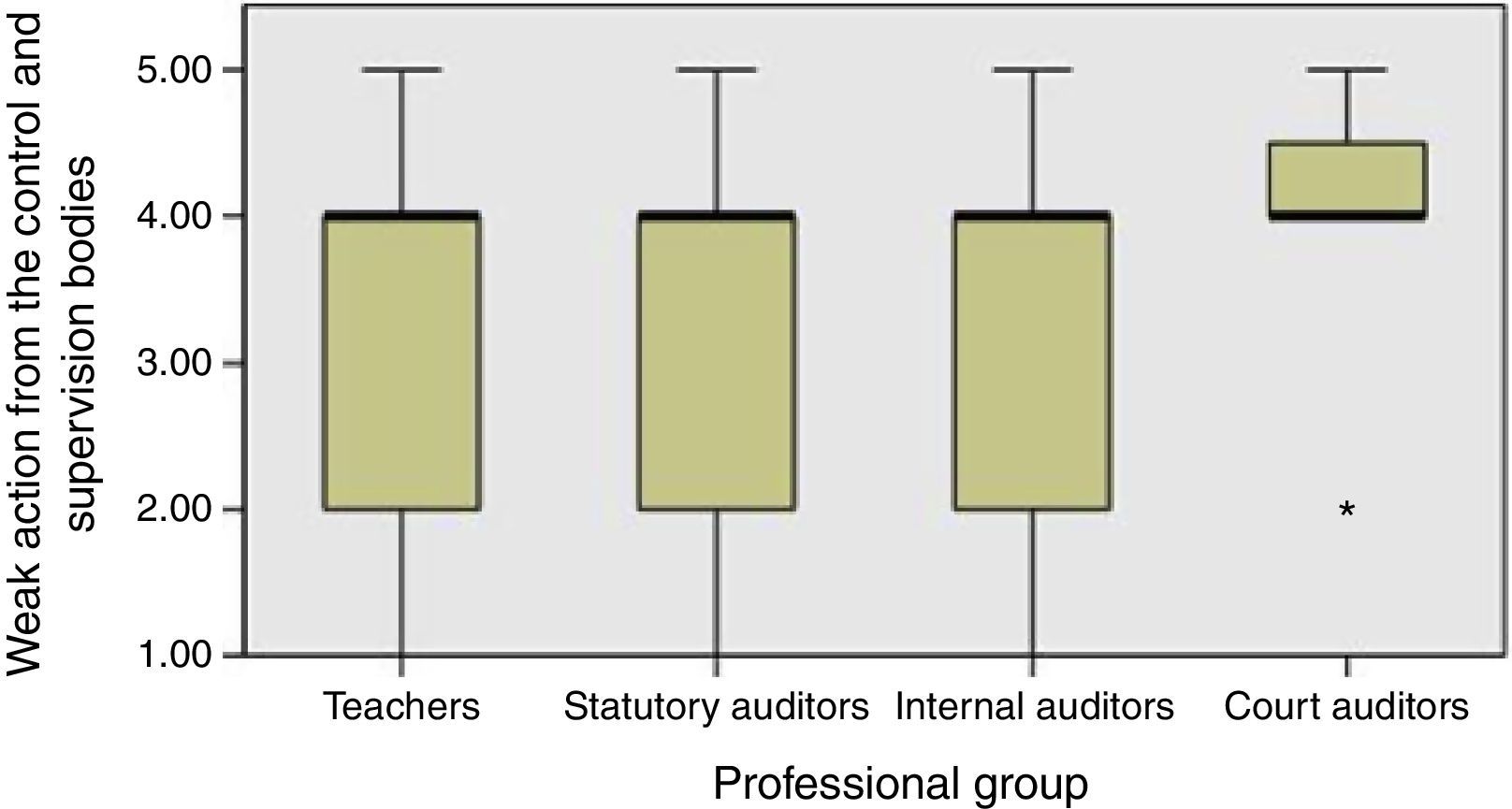

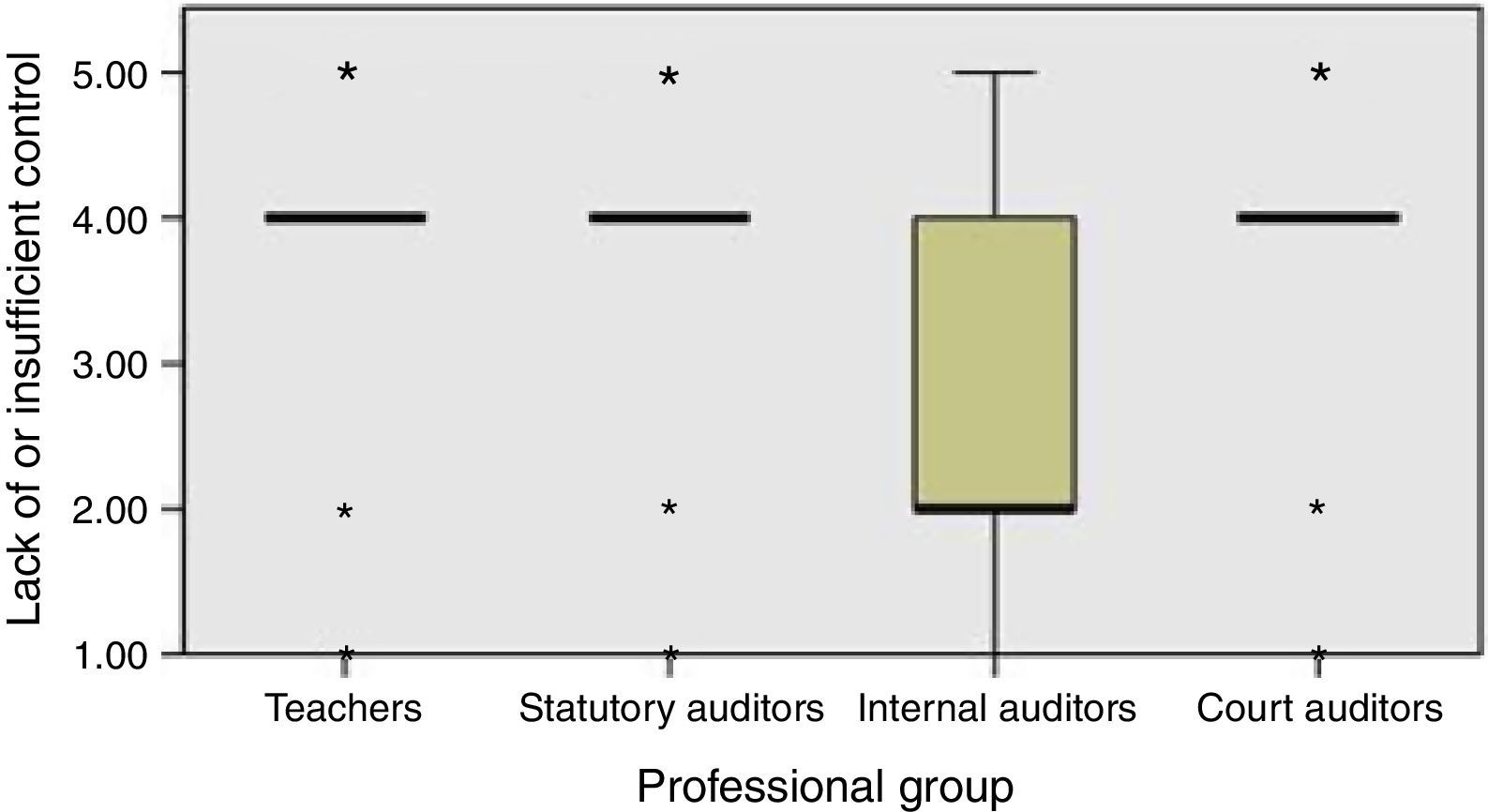

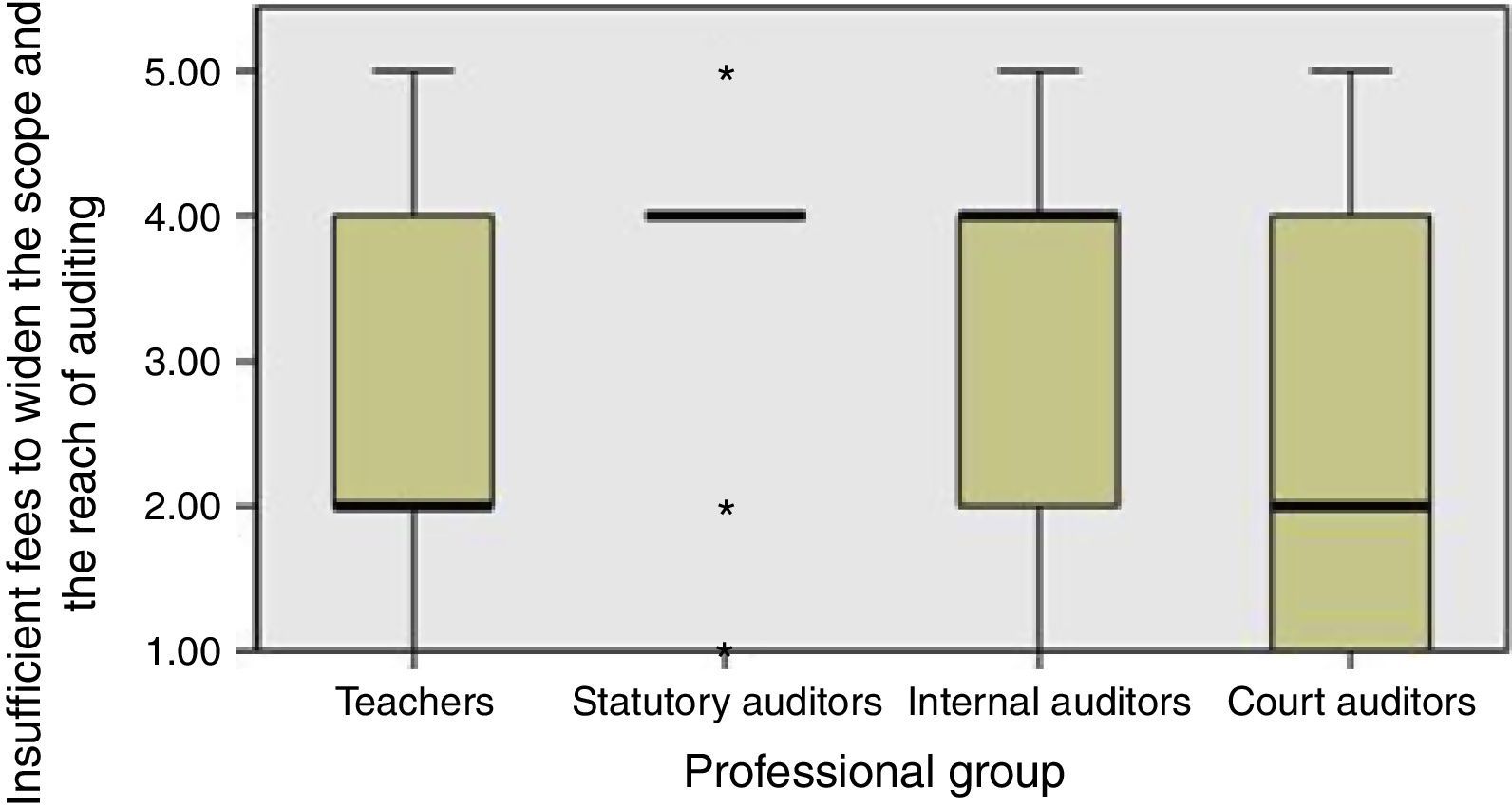

The graphs below present the results corresponding to the multiple comparisons of the means. The degree of agreement was determined based on the Likert scale from 1 to 5 points, where 1 corresponds to “Disagree totally” and 5 corresponds to “Agree totally”. The multiple comparisons of the means were determined with a significance of 5% (α=0.05). The darker line represents the mean placed between the first and the third quartile. The inferior and superior bars represent, respectively, the minimum and maximum distributions.

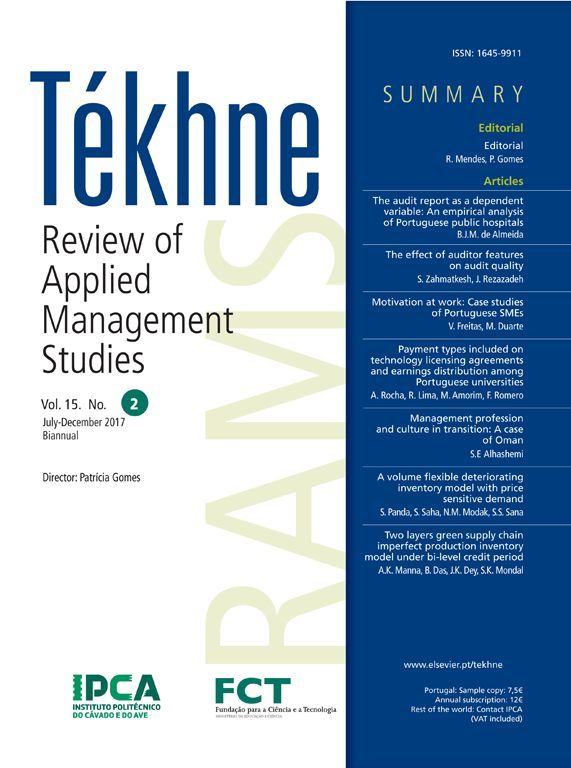

Regarding question 1.1, “Action totally independent in relation to the company”, there are statistically significant differences in the answers given by the professional groups. The results are illustrated in Fig. 1:

The analysis shows that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=31.968; p=0.000; n=447).

According to the multiple comparison of the means, the answers given by the internal auditors present statistically significant differences in relation to the statutory auditors (p=0.022) and to the court auditors (p=0.001). The teachers’ point of view is also statistically different from that of the statutory auditors (p=0.000) and the court auditors (p=0.000).

Fig. 2 represents the opinions of the various professional groups in relation to the question “Lack of training to detect errors and fraud”.

The analysis allows us to conclude that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=13.875; p=0.003; n=447).

According to the multiple comparison of the means, the answers given by the internal auditors present statistically significant differences in relation to the statutory auditors (p=0.005).

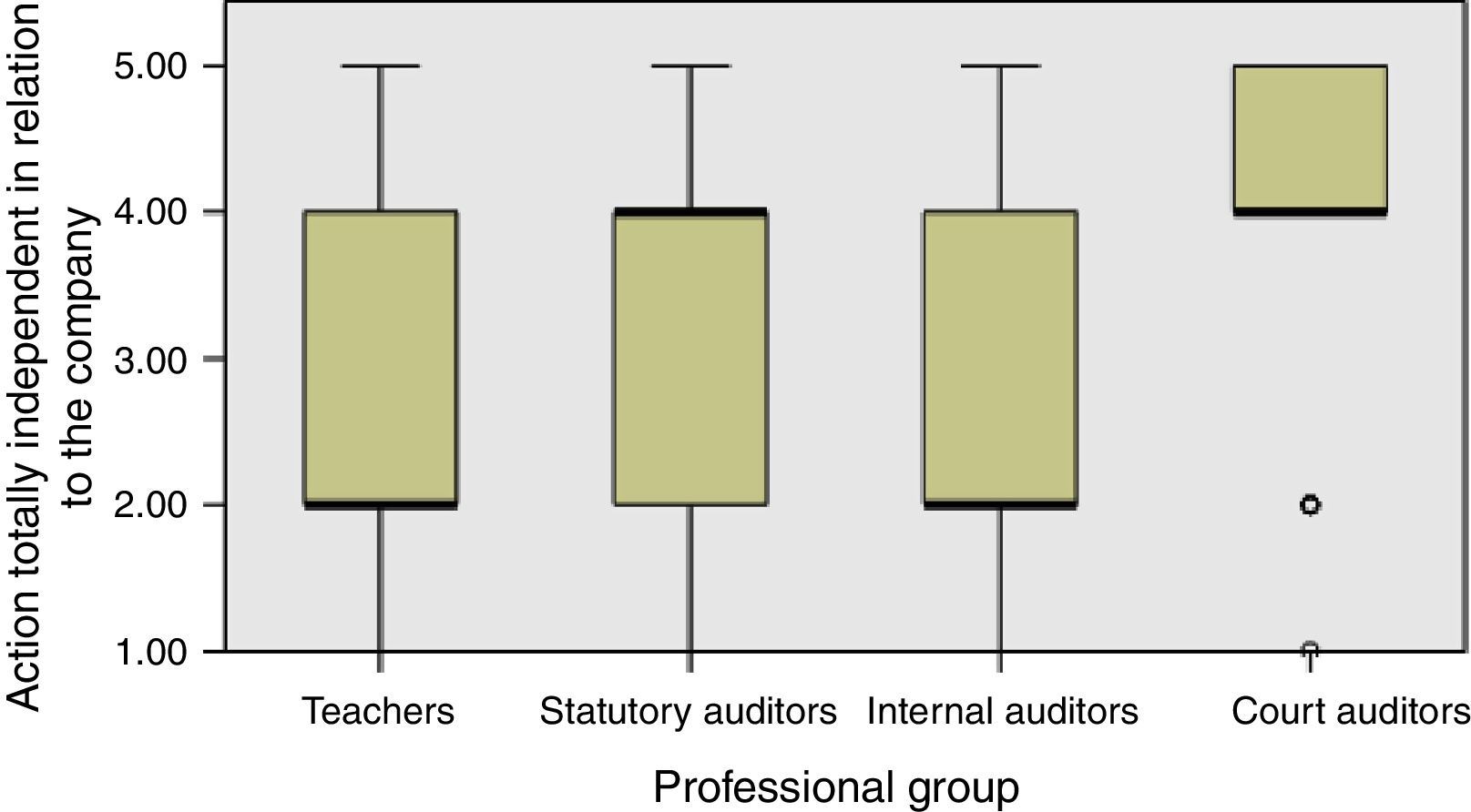

The answers to the question “No auditor rotation” is illustrated in Fig. 3.

The analysis allows us to conclude that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=7.972; p=0.047; n=447).

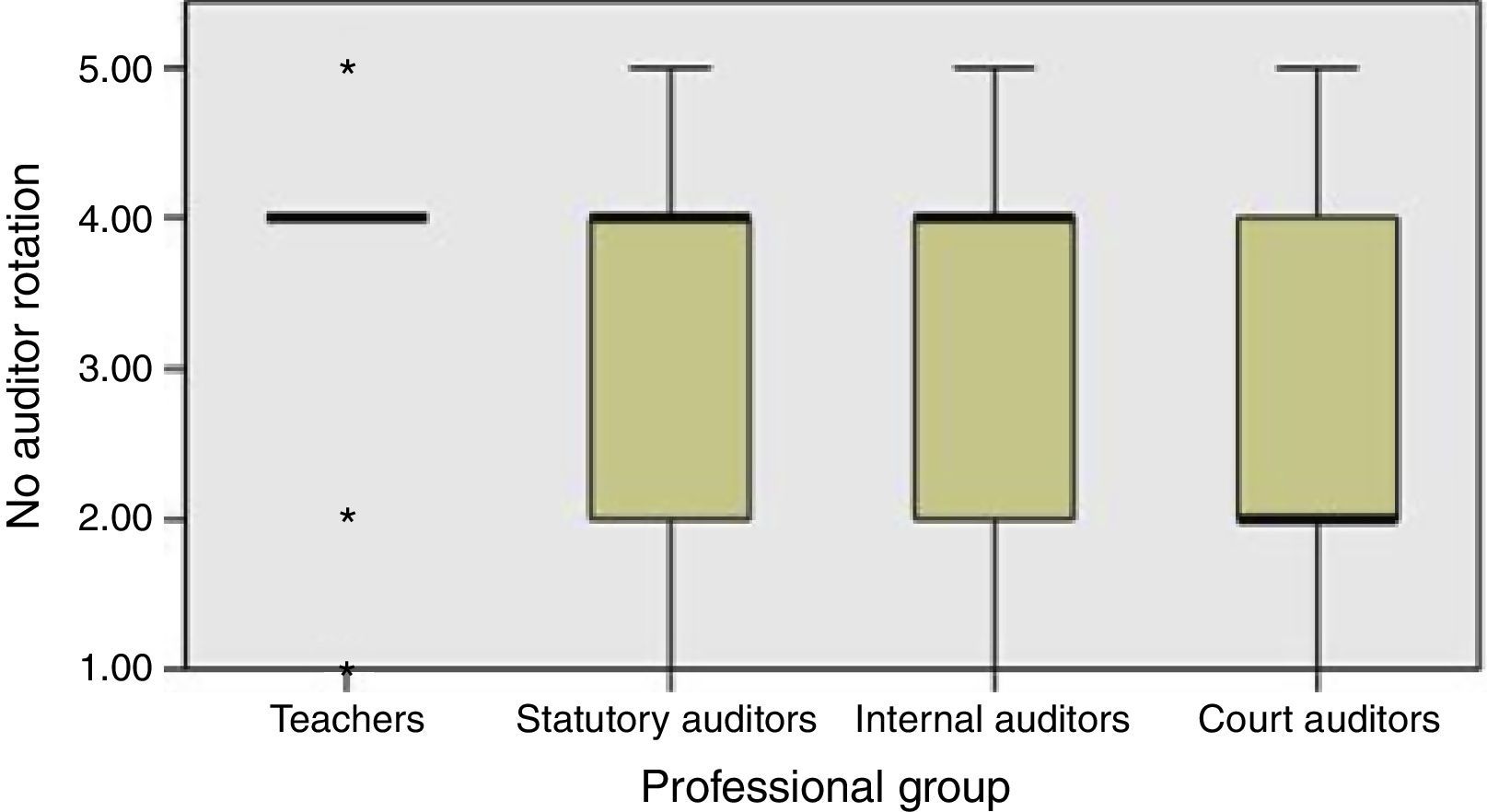

In relation to the question “Insufficient planning of audits”, the answers obtained are represented in Fig. 4.

The results allow us to conclude that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=36.248; p=0.000; n=447).

According to the multiple comparison of the means, the answers given by the internal auditors present statistically significant differences in relation to the statutory auditors (p=0.000) and to the teachers (p=0.000). There are also statistically significant differences in the answers given by the court auditors in relation to the ones given by the teachers (p=0.020) and by the statutory auditors (p=0.014).

The results obtained for the question “Unethical performance of auditors” are presented in Fig. 5.

The results allow us to conclude that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=26.053; p=0.000; n=447).

According to the multiple comparison of the means, the answers given by the court auditors present statistically significant differences in relation to the statutory auditors (p=0.000) and the teachers (p=0.001). We can also observe statistically significant differences in the answers given by the internal auditors and the teachers (p=0.006) and the statutory auditors (p=0.011).

Finally, the question referring to the “Technical incapacity of the auditors” does not present statistically significant differences relatively to each professional group. Thus, all professional groups disagree with the question.

The results related to the question “Weak action from the control and supervision bodies” are presented as Fig. 6.

The results obtained allow us to conclude that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=18.233; p=0.000; n=447).

According to the multiple comparison of the means, the answers given by the statutory auditors present statistically significant differences in relation to the teachers (p=0.005) and the court auditors (p=0.007).

The answers to the question the “Lack of or insufficient control” have been registered in Fig. 7.

Looking at the results obtained, we can conclude that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=32.436; p=0.000; n=447). According to the multiple comparison of the means, the answers given by the Internal auditors present statistically significant differences in relation to the teachers (p=0.000), the statutory auditors (p=0.000), and the court auditors (p=0.001).

The answers given to the question “Insufficient fees to widen the scope and the reach of auditing” are presented in Fig. 8.

By analysing the results obtained, we are able to conclude that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=78.891; p=0.000; n=447). According to the multiple comparison of the means, the answers given by the court auditors to this question present statistically significant differences in relation to the statutory auditors (p=0.000). There are also differences between the answers given by the teachers in relation to the internal auditors (p=0.013) and the statutory auditors (p=0.000).

The opinion of the professional groups in relation to the question “A lot of auditors/supervisors are self-employed” is presented in Fig. 9.

According to the results obtained, it can be concluded that the professional group has a statistically significant effect in relation to the answer to this question (χ2(3)=26.974; p=0.000; n=447).

By analysing the multiple comparison of the means, the answers given by the statutory auditors present statistically significant differences in relation to the teachers (p=0.000).

Finally, the answers to the question “Reduced dimension, in general, of the majority of the auditing companies”, are presented in Fig. 10.

3.4Responses to hypotheses3.4.1HypothesesHypothesis 1 (H1): There are no significant differences in the way each professional group (statutory auditors, court auditors, internal auditors, and teachers) views the auditors’ behaviour in respect to independence.

The view of each professional group in relation to the questions concerning the auditors’ behaviour is significantly different in five of the six questions asked.

The only question that obtained the agreement of all the professional groups is the one related to the technical incapacity of the auditors, with which all the professional groups disagree.

Question 1.1 “Action totally independent in relation to company”.

- •

Differences between the view of the internal auditors and the statutory auditors (the highest agreement is among the statutory auditors).

- •

Differences between the view of the internal auditors and the court auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the court auditors).

- •

Differences between the teachers and the statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the statutory auditors).

- •

Teachers and court auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the court auditors).

Question 1.2 “Lack of training to detect errors and fraud”.

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and the statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the internal auditors).

Question 1.3 “No auditor rotation”.

- •

Differences between the court auditors and the teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

Question 1.4 “Insufficient planning of audits”.

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and the statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the internal auditors).

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

- •

Differences between the court auditors and teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

Question 1.5 “Unethical performance of auditors”.

- •

Differences between the court auditors and statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the statutory auditors).

- •

Differences between the court auditors and teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and the statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the statutory auditors).

Thus, this hypothesis is not verified.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): There are no statistically significant differences in the way each professional group (statutory auditors, court auditors, internal auditors, and teachers) faces the action of the control structures.

The answers to both questions related to control structures present statistically significant differences.

Question 2.1 “Weak action from the control and supervision bodies”.

- •

Differences between the statutory auditors and teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

- •

Differences between the statutory auditors and court auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the court auditors).

Question 2.2 “Lack of or insufficient control”.

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the statutory auditors).

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and court auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the court auditors).

In sum, this hypothesis is not contrasted.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The perception of each professional group (statutory auditors, court auditors, internal auditors, and teachers), in relation to the auditing market, does not present statistically significant differences.

The answers to the questions related to this theme present statistically significant differences.

Question 3.1 “Insufficient fees to widen the scope and the reach of auditing”.

- •

Differences between the court auditors and statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the statutory auditors).

- •

Differences between the teachers and the internal auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the internal auditors).

- •

Differences between the teachers and the statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the statutory auditors).

Question 3.2 “A lot of auditors/supervisors are self-employed”.

- •

Differences between the statutory auditors and the teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

Question 3.3 “Reduced dimension, in general, of the majority of the auditing companies”.

- •

Differences between the court auditors and the teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

- •

Differences between the court auditors and the statutory auditors (the highest agreement was obtained by the statutory auditors).

- •

Differences between the internal auditors and the teachers (the highest agreement was obtained by the teachers).

Similar to the previous ones, this hypothesis is not verified.

4DiscussionGiven the objectives and the hypotheses formulated the study indicates that there are different lenses with which to analyse the behaviour of auditors, taking into account the specific professional field in which the respondents exercise their activity. However, all of the auditors and the teachers evaluated the auditors’ behaviour as ethical. This opinion takes into consideration that, generally, the auditors consider themselves as a group of professional with high level of ethics and, therefore, contributes to the supervision of their behaviour by associations of the class or their followers, who, by supervising and controlling the quality of their work and performance, sanction attitudes and undesirable judgements. In addition, the perception of their experience and competence are equally determining in their independence status. This assertion, in relation to the first statement “action totally independent in relation to the company”, finds its justification, and in a quantitative manner, in significant statistical differences of the ROC's and the court auditors, in relation to the perception manifested by the other groups. Indeed, the first professional group, which carries out relevant functions in the area of auditing, bases its opinion on the code of ethics, which legitimises its activity in the public interest of the profession and, this sense, it must be developed with independence of mind and independence in appearance. As for the second professional group, we can say that these enjoy a status similar to that of judges: independence, in this professional class, is also their touchstone. These results are in line with international research on this theme (Porter et al., 2008, pp. 101–159; Puttick et al., 2007, p. 142). In turn, the positions of the internal auditors and the teachers are based, respectively, on their performance in direct dependency on the management of the company (Intosai, 2009, pp. 1–8; Stewart & Subramanian, 2009, pp. 3–26; Wright & Capps, 2012, pp. 63–79), and the personal perceptions of the teachers are grounded on the observations of Beattie, Fearnley and Hines (2013, pp. 56–81), and McMillan (2004, pp. 943–953), who consider personal perceptions to be decisive in the shaping of this concept.

Turning now to the issue of auditor competence, expressed in the statements “lack of training to detect errors and frauds” and “technical incapacity of the auditors” through the multiple comparison of the averages of the associations, it can be noted that all professional groups, attribute professional expertise or relevant experience to the auditors, except the court auditors, who indicate significant statistical differences, which translates into a negative self-assessment in relation to their specific training or expertise to detect errors and frauds. In general terms, however, they reject the technical incapacity of the auditors. Further, all professional groups disagree with the statement that the performance of the auditors is unethical. In this context, it is possible to infer that the Portuguese professional groups connected to auditing accept the multidimensionality of independence, and view it as being materialised not in the abstract, but operationalised in the attributes of experience and ethical behaviour. Thus, the groups being studied do not see the concept of independence as merely being centred on technical aspects. This non-reductionist alignment is in line with the suggestions of Taylor et al. (2003, pp. 257–268) and Johnstone and Bedard (2001, pp. 1–18) who propose a conceptual structure enhanced with additional criteria in relation to those practised by SEC and AICPA, materialised in the attributes of experience or professional expertise and integrity or ethical behaviour: only those with relevant professional experience and irreproachable ethical behaviour are truly independent. Further within the group of questions related to behaviour, expressed in statements “No auditor rotation” and “Insufficient planning of audits”, it can be verified, with the exception of the court auditors, that the rotation of auditors is perceived as decisive in ensuring the independence of auditors. The non-compliance of the court auditors with this notion is based on their own experience of irremovability, as defined in its statutes, that is, the disagreement with the rotation is based on the fact that their independence, in legal terms, is ensured by a professional status identical to that of judges. All professional group agree with the rotation. In contrast, the other professional groups consider the mechanism of rotation to be an important instrument to guarantee the independence of auditors. Indeed, in terms of social identity theory, Imoniana, Bianchi and Tampieri (2013, pp. 219–240), and Bamber and Venkataraman (2007, pp. 19) suggest that the non-rotation of these professionals can lead to impairments in independence. In turn, when the statement “Insufficient planning of audits” is analysed, the responses of the professional groups differ greatly. This aspect of auditor behaviour is only opposed by the teachers, while the ROC's are divided on this question. It can be noted here that there is an evident contradiction in relation to the statement “technical incapacity of the auditors” which from the set of questions related to the behaviour of auditors is the only one for which the response of the four professional groups does not reveal significant statistical differences. In this context, the planning of the audit does not reveal, puzzlingly, for some professional groups, technical incapacity of the auditors, which they consider a Portuguese specificity. Still within this group of questions, significant associations can be found in the responses of the different professional groups between training, ethics, experience, and the rotation of auditors.

Hypothesis 2 refers to the way in which each professional group views the performance of the control structures. In spite of the existence of differences of intensity in the concordance with the questions, it can be verified that all professional groups manifest concurring opinions. At the level of significant associations all the groups surveyed relate the weak performance of supervisory bodies and the absence of or insufficient control. These control structures are of primary importance in the nomination of auditors, as well as in the monitoring of the work that they carry out. In this respect, the structures of corporate governance are decisive in the operationalization of the concept of independence and, when they are not totally independent, the nomination of the auditors is put at risk (Chan et al., 2013, pp. 1129–1147; Karasu, 2014, pp. 79–105; Rahmina & Agoes, 2014, pp. 324–331). In fact, Rahmina and Agoes (2014, pp. 324–331), Karasu (2014, pp. 79–105), Guo and Yeh (2014, pp. 96–104), Chan et al. (2013, pp. 1129–1147), Imoniana et al. (2013, pp. 219–240), Chu et al. (2011, pp. 135–153), analysed the acts of management of corporate governance structures and concluded that senior management carried out an important role in the nomination of auditors. Cohen et al. (2011, pp. 129–147) and Carcello et al. (2011, pp. 396–340) also reached the same conclusion when pointing out that the process of financial reporting is harmed when the recruitment of auditors is done without rigour and transparency. These studies and the observations carried out in Portugal dovetail with international thinking on this theme–indicating that professional groups implicitly consider that the development of legal systems and sanctions has a decisive influence on the behaviour of auditors (Yu, 2011, pp. 377–411). In fact, joint supply services have been prohibited in all countries because they compromise the criteria which shape the concept of independence in auditing (Brandon et al., 2004, pp. 89–103; Chung & Kallapur, 2003, pp. 931–955; Deloitte, 2008, pp. 1–8; Frankel, Johnson, & Nelson, 2002, pp. 747–760).

We now turn to the analysis of hypothesis 3. Here the issue is the analysis of the perceptions of each professional group concerning the auditing market. Again it is clear that the professional group has positive statistical effect in relation to the questions posed. Hence, on the demand side, the existence of a group of companies large enough to be listed on the Psi20 can be noted, and another much larger group, smaller in size, subject to statutory audits: the overwhelming majority is constituted by small and medium Portuguese companies. On the supply side, we note the existence of a high number of self-employed auditors, or auditors working in companies which offer smaller scale auditing services, situations in which concordance can be found in all those surveyed, albeit with different weightings. Indeed, the opinions of the teachers and the court auditors differ in relation to the other professional groups when they consider that the fees received by the auditors are sufficient to widen the scope and reach of auditing. In relation to the remaining issue, statistically significant associations can be found between all those questioned concerning the auditing market.

In this way, the necessity of knowing the structure and the workings of the auditing markets can be emphasised. The high concentration that can be observed worldwide suggests that larger auditing companies are capable of exercising a considerable influence on the overall market (Benau, 1998, pp. 51). In fact, the companies that audit the listed companies on the Lisbon stock Exchange–Psi20 – together make up approximately 90% of the Portuguese auditing market (Machado de Almeida, 2012, pp. 12–54). Hence, by using concepts of industrial economics there is a direct relationship between the degree of concentration of auditing markets and economic development (Benau, 1998, pp. 54): Portugal, for its part, does not escape this rule. The fragility of the structure of Portuguese supply, generally speaking, is perceived by the respondents as promoting potential impairments, regarding the designation of the auditor, (Carcello et al., 2011, pp. 396–430; Chu et al., 2011, pp. 135–153; Martinov-Bennie et al., 2011, pp. 656–671), which is related to the supply structure generally characterised by small businesses. In addition to this characteristic, to analyse more fully the workings of the Portuguese auditing services market, similar to the studies of Li (2009, pp. 201–230), and Porter et al. (2008, pp. 103–156) it is necessary to analyse the component of fees: it is clear that there is a perception, on the part of the teachers and court auditors, that the fees paid to auditors are high, a perspective which the other groups reject.

5ConclusionsThis study examines the criteria accepted by international organisations to assess the threats to independence in auditing through a set of questions to operationalise, in general terms, the criteria, and which are related to the fundamental objectives of the study. The statistical treatment carried out allows us to assert that the behaviour of the auditors, in terms of independence, in Portugal, is not unanimous. There are notable divergences according to the professional group being considered. Although, broadly speaking, the professional group of auditors (ROC's and ATC's) as a majority respond that they perform in an independent way, the high number of dissenting responses nonetheless remains alarming, a situation that deserves significant reflection. In turn, the other professional groups are peremptory in their affirmation that independence does not exist in the profession. Further, the existing control structures, and corporate governance, are perceived as being insufficient in terms of performance, which raises problems for independence. The auditing market, from the point of view of supply and demand, is characterised, broadly speaking, by small companies, and the professionals questioned help to ensure – directly or indirectly – that this situation has an influence on independence in auditing.

5.1Limitations of studyEmpirically, the study clearly has limitations. Firstly, in relation to the sample and the information collated on the internal auditors, which was unable to obtain more than 18%, and which is also reflected in the other professional groups. Secondly, the questionnaires were applied to the actual professionals that carry out audits or teach auditing, a situation which can influence the responses. Further, the questions posed can be considered too broad or too restrictive, and therefore can influence the responses. Finally, it should be stressed that the dynamic nature of the actual concept of independence may distort the responses.

5.2Suggestions for future researchThe problem of independence in auditing is a central issue in the relationships of accountability in modern society and should, therefore, be the subject of greater theoretical and empirical analysis, with future research analysing the relationships established between the auditors and their clients in the light of social identity theory – which suggests, with the continued renewal of mandates in audited companies, the existence of independence impairment.