This paper is a meta-review of public sector performance management research as published over the last decade. Contingency-based studies are the predominant types of research on public sector performance management, but the review points to a lack of consistent evidence of which contingency variables are influential under which circumstances. The paper also indicates that a variety of research questions in this field can be addressed by different theories, especially coming from economics, organization theory and institutional sociology. Finally, a set of underdeveloped research areas are highlighted: (1) more extensive theorizing as opposed to the mainly pragmatic perspectives currently adopted; (2) inclusion of ‘hard data’ in the analysis of organizational performance; (3) taking a broader perspective on transformation processes, that is, other than the simple fabrication trajectory, particularly complex project-type of processes and network organizations; (4) benefiting from insights of performance management research in the private sector, for example about pay-for-performance systems.

Performance measurement and management have become one of the most prominent and relevant research issues in public administration and management. It is an ongoing topic of conferences and of books and journal articles. The body of knowledge has considerably grown over the last decade. A large amount of literature in this field has a dominant prescriptive approach and aims to contribute to the improvement of public sector performance. However, there is also a remarkable body of literature dealing with analytical, theoretical and explicative aspects of public sector performance. It has become increasingly difficult to navigate through the complex variety of research findings in this field.

The goal of this article is to find a path and to take stock of the existing knowledge in public sector performance management research, by conducting a kind of “meta-review”. We selected ten articles which themselves aim to critically assess the existing literature on performance measurement and management, and try to review these articles at a meta-level. More specifically our goal is to take stock of some of the relevant findings of research in this field, to identify the important influential factors and effects of public sector performance as reported by the reviewed literature, and to determine gaps and open or controversial issues in this research field. Our study of the review-papers will also take a view on the theoretical concepts and approaches which the authors of those papers used for understanding and explaining certain causes, relationships and effects of identified research results.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 introduces the design of our review. Section 3 presents some of the major findings of research in performance measurement and management as presented in the underlying review-papers. Section 4 reviews important theories that explain performance measurement design and use issues. Finally, Section 5 points to a set not only of underdeveloped research areas but also of open methodological and theoretical issues in the domain of public sector performance measurement and management.

2Review design2.1Definitions and concepts of performance“Performance” is a complex concept and can be seen from different angles (e.g. van Dooren, Bouckaert, & Halligan, 2010, 16–20). It is at first the result of a production process where inputs are transformed via activities into outputs and finally result in various outcomes. Furthermore, performance can be seen as the realization of certain public values. Generally, performance is related with the “3E's” (economy, efficiency, effectiveness) and additionally with equity. To deal with performance implies to at first measure it and secondly to take action, for instance, to improve performance. Measuring performance is related to the determination, estimation and assessment of certain information about planned or achieved performance. Usually, a set of performance indicators is identified and measured for that purpose.

Performance measurement – as understood in this paper – concerns the measurement of performance indicators considered as relevant and useful by decision makers in public sector organizations for a broad variety of purposes, such as planning and control, learning, accountability and evaluation, including the reporting of these indicators. Performance management can be seen as a particular way of using the results of performance measurement for managerial purposes, e.g. for planning and control. The targeting of performance indicators and the analysis of variances between targeted and realized numbers of performance indicators are the main elements of performance management.

Performance measurement and management are an issue in the private enterprise sector as well as in the public sector. In the latter it is much more complicated as performance is also covering a lot of external factors and effects, e.g. the policy outcomes of a certain policy regarding certain target groups. In this paper, we perceive the public sector in a broad sense: it covers activities and services not only in core government and in the various public sector organizations, but also services which are supplied by organizations outside the public sector but regulated and partly funded by the public sector, for example in health care and education. In the following we focus on the results of research dealing with public sector performance management (PSPM) which also covers performance measurement.

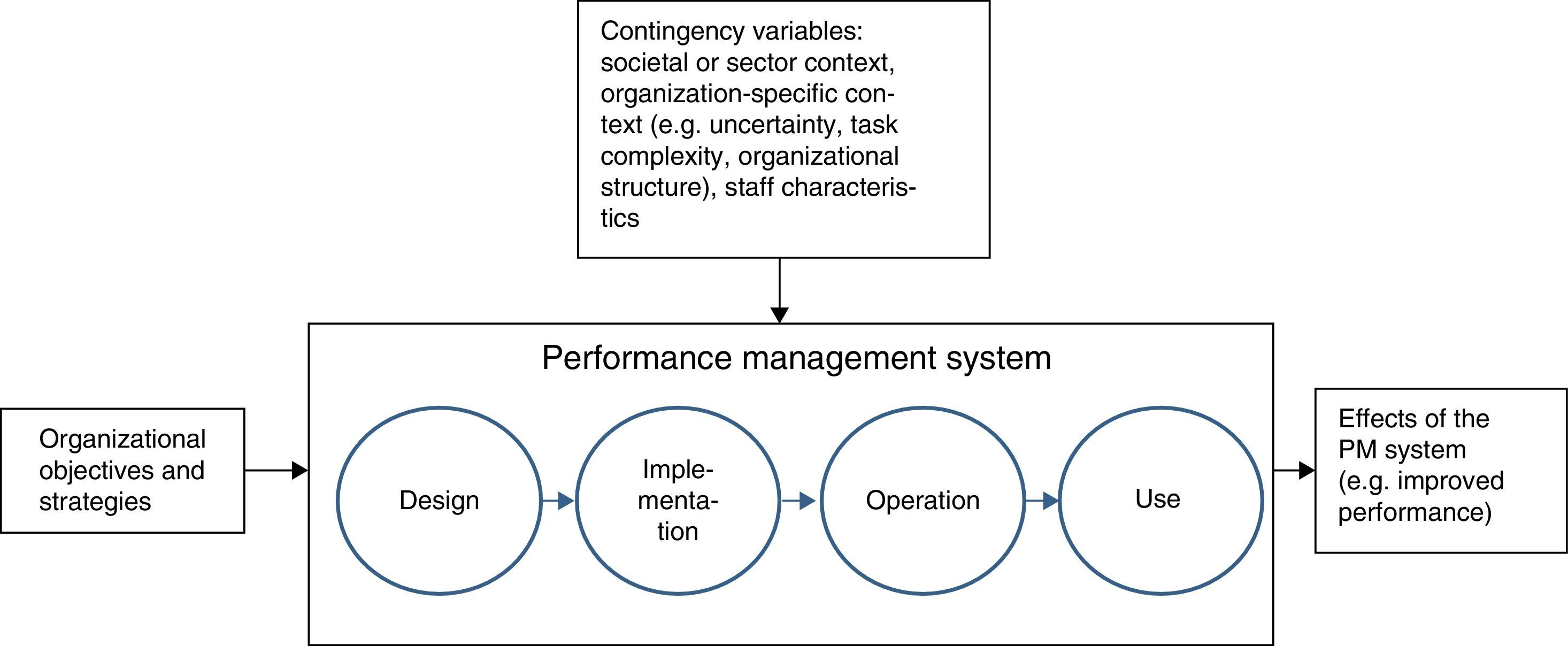

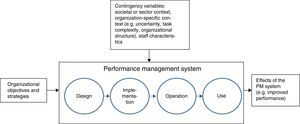

2.2Framework for a meta-reviewFig. 1 portrays a framework for our analysis of a public sector performance management system.

The figure shows at first that a performance management system can be split up into different phases of its development. The first stage of the life cycle of a PSPM-system is its design (see for the life-cycle approach in relation to performance management: van Helden, Johnsen, & Vakkuri, 2012). Subsequently, the system has to be implemented in a public sector organization. After implementation the system will be in operation, that is, it measures regularly certain aspects and elements of performance and it provides the results of the performance measurement to the users of the system. The final stage of a PSPM-system is the use of the provided performance information by the users for different purposes, e.g. budgeting or policy decisions.

The figure assumes that the objectives and strategies of a public sector organization are important drivers of a PSPM-system; they have considerable impact on the design of the system and as such on the types of selected performance indicators and the related targets. On the other side, the operation and use of a PSPM-system have various effects on the organization's performance, especially in terms of effectiveness (i.e. outcomes on, for example, target group reach and service quality) and on efficiency (e.g. cost of services). Additionally, other effects of practising such a system may also occur (e.g. unintended policy effects).

The design and the functioning of the PSPM-system also depend on several contingency variables. These variables can refer to the societal and the sector level, for example to general NPM-like trends in society towards making public sector organizations more business-like or to imitate private management concepts. Furthermore, there are various organization-specific variables, such as task complexity, uncertainty, flexibility and culture. The inclusion of this type of variables may involve assumptions like ‘the higher the task complexity, the more variation in the types of performance indicators.’ In addition, contingency variables on the level of individual decision makers – politicians and managers – can be distinguished, such as their information processing capacity or risk attitude. An adequate match between contingency variables and the PSPM-system is supposed to contribute to organizational performance, whereas a mismatch is considered harmful.

A PSPM-system has several purposes and functions. In many studies the planning and control function of the system plays a central role. A PSPM-system can, however, also have other functions, particularly the accountability function and the evaluation function (e.g. offering information about the effectiveness of governmental programmes to a variety of stakeholders). Depending on the function, the content of a PSPM-system – for example, the types of performance indicators – may differ (Behn, 2003). Implicitly, the figure conceptualizes decision makers in the organization as rational in the sense that their behaviour is goal-driven and that the PSPM-system is a result of this type of behaviour. Decision makers in public sector organizations, however, can also be driven by other forms of rationality, such as political rationality (see for example ter Bogt, 2001; Johnsen, 2005).

Depending not only on the objectives and strategies of an organization but also on the different contingency factors, the design of a PSPM-system can have a quite different focus on the kind of performance elements to be identified, measured and reported. In a quite narrow view, it may concentrate primarily on quantitative input-output relations (efficiency). In a more broad and comprehensive perspective, it will additionally cover the relations between certain outputs and intended (or even: unintended) intermediate or final outcomes (effectiveness). Additionally, such a system may also cover aspects of the quality of outputs and outcomes and/or the effects on equity (e.g. for certain target groups). The measurement/estimation of policy-related outcomes of a certain government activity or a public service is in most cases complicated, as direct causal links between governmental activities, immediate outputs and outcomes are rather exceptional.

Particularly for the “use”-phase of a PSPM-system the differentiation among supply and demand is of some relevance. On the one side there is a certain “supply” of performance information, e.g. within regular performance reports. On the other side, there is the “demand” of users (e.g. decision makers, external oversight bodies) concerning the provided performance information. The demand of decision makers for performance data depends on various factors, such as the appropriateness of the data (Brun & Siegel, 2006) as well as the willingness and ability of the user and thus on a variety of individual factors like qualification, values, traditions, experience (see e.g. Yamamoto, 2008).

2.3Selection of review papersOur analysis is based on a collection of ten articles which have been selected from the vast stock of research publications on PSPM. The articles can be differentiated into two types of review papers: (1) systematic reviews consisting of clearly identified categorizations of selected sets of papers, and (2) reflective reviews presenting relatively more interpretive (but hopefully challenging) views on the available literature. The focus of the first type of review-article is quite strictly on the systematic analysis and comparative assessment of a series of articles dealing with PSPM. The underlying articles of type 1 clearly refer to a variety of literature sources (journal articles, books). Usually, a type 1-article presents certain typologies or classifications of findings derived from the reviewed literature, in terms of, for instance PSPM topics, theories and methods. Reflective reviews are also based on a substantial and in-depth analysis of other publications. However, the analyses are less systematic, authors just pick-up some thoughts and findings from the reviewed publications but do not offer a systematic evaluation and comparative assessment of the literature under review. The interface between “reflective reviews” and other academic papers dealing with PSPM is rather “fluid”, as the majority of academic articles includes some kind of a literature review.

The ten selected review articles originate from two different research fields: Six of them cover the whole public sector; they are mainly based on more general academic journals in public administration/management (and other types of academic literature in this field). The other four review articles are focusing on accounting, that is, they review relevant sources in the field of public sector accounting, including performance management.

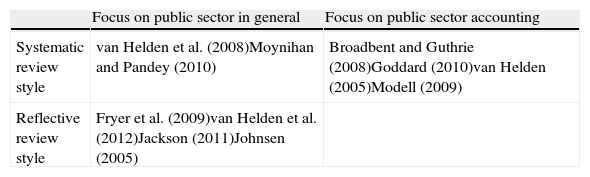

Table 1 provides an overview of the different perspectives and the underlying sources of the selected review articles.

Style and focus of reviewed articles.

| Focus on public sector in general | Focus on public sector accounting | |

| Systematic review style | van Helden et al. (2008)Moynihan and Pandey (2010) | Broadbent and Guthrie (2008)Goddard (2010)van Helden (2005)Modell (2009) |

| Reflective review style | Fryer et al. (2009)van Helden et al. (2012)Jackson (2011)Johnsen (2005) |

Due to the New Public Management (NPM) trend public sector performance management has clearly gained momentum during the past two decades. Thus, our analysis is particularly focussed on findings which incorporate experiences of this development. This is why the selected review papers all date from the last ten years. Our meta-review merely focusses on review articles published in international research journals. The broad array of books on PSPM is not covered by our meta-review (see for example, Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008; de Bruijn, 2007; van Dooren et al., 2010; Talbot, 2010). This may be regarded as a limitation of this meta-review. The list of review articles is included as an appendix at the end of this paper.

The selected review articles all have a distinct research interest and approach. Most concentrate on the analysis and critical evaluation of the literature under review. Other articles (e.g. Moynihan & Pandey, 2010) also present the results of own empirical studies. Again other articles have a clear theoretical interest and use the reviewed material primarily for further developing explanatory concepts (e.g. Modell, 2009). Furthermore, the spectrum of literature analysis of the selected review articles is quite different. Some of them cover a broad choice of international journals, whereas others concentrate on literature from Europe.

3Contingencies of performance management: some results of PSPM-research3.1Major results of PSPM-research based on the reviewed articlesAll selected articles aim to take stock of the state-of-art of PSPM-research. They emphasize the extended spectrum of this research field and the increased intensity of research. Most articles, however, also confirm the incompleteness and inconsistence of research results. There are still various open issues and unsolved problems which range from PSPM-design to PSPM-impacts. Some examples amongst others: the reviewed authors observe modest knowledge about appropriate measurement of outcomes and qualitative policy effects, about the reasons why certain user groups are reluctant to use provided performance data, or about the effects of a PSPM-system on organizational performance, on accountability and other possible purposes.

Various review articles offer a concise overview about important findings of PSPM-research. In the last decade an increased implementation of performance measurement and management systems can be observed in public sector organizations. Not surprisingly, these systems produce and provide a large variety of performance information; mostly on quantifiable outputs and only modestly on outcomes and on issues of service quality. Furthermore, the review articles point to a controversial, at least inconsistent picture of performance information (PI)-use. One reason for such inconsistency of research results is the difficulty to assess the impact of various influential factors on the ability and willingness of stakeholders to use the provided data (see next section for details). Several articles emphasize that during the high tides of NPM the positive effects of performance management on the steering and controlling of public sector organizations and on their performance have been overestimated. Later it was discovered that different variants of misuse and several dysfunctional effects of performance measurement exist, e.g. symbolic use of PIs, negligence of qualitative aspects, misuse of data for personal interests, etc. Finally, the papers substantiate that the knowledge about the impact of PSPM-systems on different outcome variables, e.g. on efficiency and effectiveness of an organization, on accountability or other major possible purposes of a PSPM is rather limited. Not surprisingly, some authors observe a changing emphasis over time from the design phase of a PSPM to the operation and use phase. This is in line with the attention in PSPM-practise, because in the earlier times there was a great need to design and to establish such systems and only later to reflect about possible reasons why expected targets of performance measurement and management could not be achieved.

Some review articles discuss the research design and the methods used in PSPM-research. Considerable variation is observed between researchers in Europe and in the U.S. While case studies seem to be dominant for European researchers, survey-based research approaches are more visible in the US-community (Goddard, 2010, p. 80; van Helden, 2005, p. 108; van Helden et al., 2008).

The use of theories for explaining and understanding issues of PSPM is – at least in some review articles – not very explicit. van Helden (2005, p. 109) signals that several authors of the underlying literature do not apply at all a theoretical framework for analysing their research results There is, however, a tendency towards more theorizing and more analytical research (Goddard, 2010, p. 84). More details of theory use in PSPM are in Section 4.

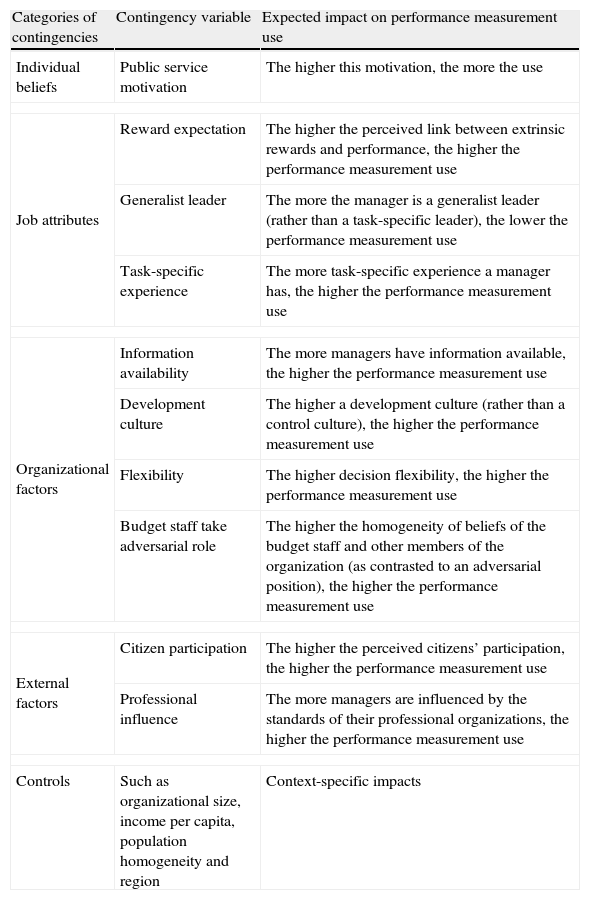

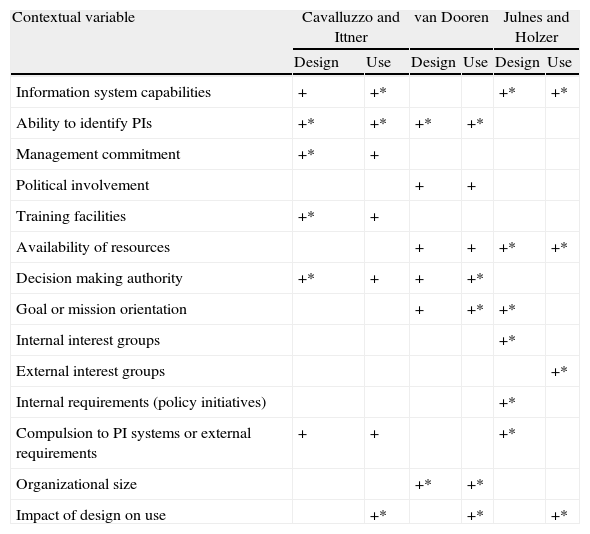

3.2Contingencies of performance managementAccording to Moynihan and Pandey (2010) the examination of antecedents of the use of performance information can be regarded as one of the most intriguing research topics. These antecedents which have the character of independent or intermediate variables regarding to PSPM apply to several levels, such as the organizational and the individual one. Table 2 gives an overview of possibly relevant antecedents as included in Moynihan and Pandey's review (see Kroll, 2012 for a similar review).

Overview of contingency variables in the research on performance information use.

| Categories of contingencies | Contingency variable | Expected impact on performance measurement use |

| Individual beliefs | Public service motivation | The higher this motivation, the more the use |

| Job attributes | Reward expectation | The higher the perceived link between extrinsic rewards and performance, the higher the performance measurement use |

| Generalist leader | The more the manager is a generalist leader (rather than a task-specific leader), the lower the performance measurement use | |

| Task-specific experience | The more task-specific experience a manager has, the higher the performance measurement use | |

| Organizational factors | Information availability | The more managers have information available, the higher the performance measurement use |

| Development culture | The higher a development culture (rather than a control culture), the higher the performance measurement use | |

| Flexibility | The higher decision flexibility, the higher the performance measurement use | |

| Budget staff take adversarial role | The higher the homogeneity of beliefs of the budget staff and other members of the organization (as contrasted to an adversarial position), the higher the performance measurement use | |

| External factors | Citizen participation | The higher the perceived citizens’ participation, the higher the performance measurement use |

| Professional influence | The more managers are influenced by the standards of their professional organizations, the higher the performance measurement use | |

| Controls | Such as organizational size, income per capita, population homogeneity and region | Context-specific impacts |

This type of research can be considered as an application of contingency theories. This type of theories emerged in the 1960s and 1970s in organization theory but also in different parts of behavioural theories (e.g. Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967; Pugh & Hickson, 1976; Fiedler, 1967). Its main argument was that there is no one best solution, e.g. in structuring organizations or in leadership styles. Rather, a solution is contingent, that is, structural or behavioural alternatives are depending (or: contingent) on various internal and external situational factors. Although the early concepts of organizational contingency theory were several times criticized (e.g. Hinings et al., 1988), the approach is still attractive for explaining interrelations between different variables in organizational and behavioural studies (e.g. Donaldson, 2001).

The contingency perspective has also been applied in accounting research. In his review of contingency research in management accounting Chenhall (2003) distinguishes two types of contingency models: one constrained to investigating the extent of the fit between contingency variables and the use of management accounting tools (such as a PSPM-system) and the other focussing on the relationship between this fit and organizational performance. The latter type is more ambitious because it requires evidence that the contingency fit is effective, in the sense that the contingency fit leads to enhanced organizational performance.

Apart from the Moynihan and Pandey-paper, the other review papers of this meta-review are not very explicit on identifying contingency factors. The following factors (as far as not yet mentioned in Table 2) were discussed in some of the selected review papers (particularly in: Fryer, Antony, & Ogden, 2009; Johnsen, 2005; van Helden et al., 2008, 2012):

- •

goal and result orientation

- •

decision-making authority

- •

role of stakeholders

- •

organizational size

- •

technical capacities

According to the literature review of Kroll (2012, pp. 21–24), the maturity of the implemented performance measurement system is another relevant influence factor. At the level of the individual user of performance data, several contingency factors seem to be relevant (Kroll, 2012):

- •

user involvement in customizing performance information (positive effect)

- •

cynicism (negative effect)

- •

public service motivation (PSM) (weak and ambiguous effect; see also Kroll & Vogel, 2013)

Analytical skills of users, education and professional/job experience seem to be less relevant.

Furthermore, the kind of performance information which is produced and provided to decision-makers and other types of “users” also plays an important role. Contrary to the widespread assumption that systematic and regularly provided quantified data is most relevant for the users, there is quite some evidence that non-systematic, more narrative information is equally if not more important for the users (Kroll, 2013; ter Bogt, 2001, 2003).

3.3Illustrations of contingency-based PSPM-researchIn the following we want to deepen the discussion about contingency variables having a possible impact on PSPM. Here we concentrate on two stages of the PSPM-lifecycle which were of particular interest in recent PSPM-research: the design of the system and the use of performance information. Table 3 provides some illustrations of such interrelations. As the underlying review papers do not offer sufficient information about such variables, three different empirical papers on performance measurement and management have been selected. All of them are recent survey studies but the research was conducted from different disciplinary perspectives: accounting (Cavalluzzo & Ittner, 2004), public management (van Dooren, 2005) and public administration (de Lancer Julnes & Holzer, 2001).

Influence of contingency variables on public sector performance management design and use.

| Contextual variable | Cavalluzzo and Ittner | van Dooren | Julnes and Holzer | |||

| Design | Use | Design | Use | Design | Use | |

| Information system capabilities | + | +* | +* | +* | ||

| Ability to identify PIs | +* | +* | +* | +* | ||

| Management commitment | +* | + | ||||

| Political involvement | + | + | ||||

| Training facilities | +* | + | ||||

| Availability of resources | + | + | +* | +* | ||

| Decision making authority | +* | + | + | +* | ||

| Goal or mission orientation | + | +* | +* | |||

| Internal interest groups | +* | |||||

| External interest groups | +* | |||||

| Internal requirements (policy initiatives) | +* | |||||

| Compulsion to PI systems or external requirements | + | + | +* | |||

| Organizational size | +* | +* | ||||

| Impact of design on use | +* | +* | +* | |||

Legend: A number of cells show whether a positive relationship was expected (sign +), supplemented with an asterisk (*) if the relationship is significant at least at a .10 significance level (if no * is given, the relationship is not significant). If no entry: the item was not measured.

Cavalluzzo and Ittner (2004) conducted a survey study into the development and use of performance measurement by government organizations, particularly federal state agencies in the US. The first column shows which contingency variables – according to these authors – influence the design of performance management systems. We see that four contingency factors have impact on the PSPM-design while two other variables (information system capabilities and compulsion to performance management systems) do not have. Table 3 also indicates that only information capabilities and the ability to identify PIs are influential on the use of performance management. Furthermore, the last row in the table indicates that design and use of a PSPM are positively related.

van Dooren's (2005) study is a survey-type study on the design and use of PSPM by sections within the Ministry of the Flemish Community in Belgium. van Dooren's study shows that two factors particularly influence design: the ability to identify PIs and organizational size. These factors also positively influence use, which is additionally impacted by decision making authority and goal orientation. This can be explained by the fact that organizations may introduce PIs, but in order to use them they need to be linked to goals. van Dooren also concludes that design and use are positively related.

de Lancer Julnes and Holzer (2001) present a survey held on different levels among managers in public sector organizations (central, intermediate and local level) of the US government. They argue that design is primarily influenced by elements such as external requirements, resources, goal orientation, information capabilities and the involvement of internal groups, and that use is mainly determined by resources, information capabilities and the involvement of external groups. Again, the authors conclude that design and use are positively related to each other.

We can make the following observations. First, there is only limited consistent evidence across the three studies on the influence of contingency variables on the design and use of performance management systems. Only the ability to identify PIs and – to a lesser extent – decision making authority and goal or mission orientation are influential in more than one study. This implies that institutional settings matter, such as the level of government and the type of organization, and that they will need to be made explicit in future research. Second, although design and use are positively correlated, their interdependency requires further examination, for example with respect to the types of variables that are positively related to use but not to design, such as goal orientation and systems capabilities to measure PIs. Third, the studies can be considered as so-called ‘constrained contingency-based’ examinations because the fit between contingency variables and the performance measurement design and use is not related to the ultimate organizational performance of a public sector organization (see Section 3.2).

A few studies take a broader view on the interrelations between contingency variables, the PSPM-system and the organizational performance of the respective public sector organizations. One study is by Verbeeten (2008) who relates clearness of goals and performance measures as well as incentives for managers as contingency variables to organizational performance. The author refers to goal setting theory which suggests that clear and measureable goals are positively related to quantitative performance (such as outputs numbers and efficiency), but not to qualitative performance (as regards, for example, service quality or employee satisfaction). The survey study among managers of a Dutch governmental organization however shows that clear and measurable goals do have a positive impact on both quantitative and qualitative performance. The author also refers to economic theory which indicates that incentives (especially pay-for-performance systems) are positively related to quantitative performance but not to qualitative performance. This latter assumption is confirmed by the study. Verbeeten (2008, p. 442) warns that performance measurement practices may be less suitable for organizations relying on quality service dimensions which are difficult to measure. A study of Abernethy and Lillis (2001) shows that there is a need to establish a fit among strategy, structure and the PSPM-system. This may result in better organizational performance, measured both in terms of efficiency and effectiveness.

The presented illustrations of implications of different contingency variables on PSPM confirm the received picture of inconsistency of empirical findings and of limited knowledge. We observe a lack of clear and consistent evidence of which contingency variables are influential under which circumstances on the design, implementation, operation and use of a PSPM and also a lack of empirical knowledge on the effects of PSPM on organizational performance.

3.4Critical assessment of contingency-based researchIn this section we present some critical observations. First, as shown in the last section, some studies are based on a constrained version of the contingency model because the fit between contingency variables and a PMS is not related to organizational performance. Second, contingency-based studies are intrinsically concerned with more or less stable circumstances in which a PSPM-system is clearly aligned with its context. Processes of adaptation, for example through learning (or more general, experience) are disregarded. Third, the contingency model only provides a general framework for modelling the explanations for performance measurement design and use. Its academic rigour depends to a large extent upon the particular theories adopted for explaining the associations between contingency variables, the PSPM-system and organizational performance. Finally, there is a methodical restriction which can often be observed in contingency-based PSPM-research: the method of self-reporting. The results of such research are to some extent doubtful because of their subjectivity, if organizational performance is measured (only) by asking managers about their individual perception of the level of performance of their organization. This limitation can, however, be eased by including also other respondents (politicians, citizen representatives, colleagues) in such surveys.

4Theoretical approaches used in PSPM researchSome of the selected review articles also provide information about the theoretical approaches which are applied for explaining certain observations and findings in the respective underlying literature. Goddard (2010), van Helden (2005) and van Helden et al. (2008) have found that apart from other theoretical concepts (e.g. from Political Science (for instance rational choice), Sociology or Social Psychology) particularly the three following theory bundles have been relevant in PSPM-research:

- •

variants of economic theories, e.g. agency theory or transaction cost theory

- •

variants of organization theories

- •

variants of (sociological) neo-institutionalism

Economic theories are used in some studies for explaining the selection of particular performance indicators. Such theoretical concepts can also be used from a prescriptive view, e.g. to assess the contribution of performance indicators for improving decision making and control, and to compare such improvement with the costs of developing, measuring and reporting these indicators (see Perego & Hartmann, 2009). Another way of economic reasoning, which relies on agency theory, concerns the effectiveness of incentives for managers, such as bonus systems. A relevant research issue here is: To what extent does a pay-for-performance system which is based on performance indicators, contribute to an enhanced organizational performance (see further Section 5)?

Organizational theories offer a very broad choice of different approaches and explanations (see for an overview e.g. McAuley, Duberley, & Johnson, 2007). Some of them can be used to understand and to interpret the reactions of organizational units or actors on the implementation of a PSPM-system, or to explain the impact of performance information on organizational performance. Aidemark (2001), for example, used Ouchi's management control theory for an understanding of the change in the control repertoire through the introduction of a Balanced Scorecard in a Swedish hospital. According to Ouchi's management control framework, a hospital is often regarded as a clan-type of organization and thus not amenable to measurement, but the hospital professionals appreciated the Balanced Scorecard as a means to present a balanced picture of the health care activities as an alternative to financial statements, which gave rise to output and throughput control types.

Concepts of Neo-institutionalism (also called sociological institutionalism or institutional sociology) explain the evolution of organizations and the behaviour of actors in organizations from an institutional view. According to these concepts, institutions like rules, traditions, expectations, symbols, cultures have a strong impact on individuals and organizations (see e.g. Powell, 2007; Scott, 2001). Neo-institutionalism is closely related with Organization theories. In our field of PSPM, Neo-institutionalism can for instance explain why bureaucrats choose a “fashionable” PSPM-design (isomorphism) or why politicians are reluctant to use performance information (tradition and logic of appropriateness). Generally, Neo-institutionalism can provide explanations for the understanding of the design and use of performance information, that is, by pointing to institutional forces, including ways of thinking of politicians and managers. Within the selection of our review papers, the article of Modell (2009) is an excellent example for the use of Neo-institutionalism for PSPM-research. Modell reviewed various papers explaining public sector performance management on the basis of neo-institutional approaches. Modell shows that neo-institutional studies focus more on adaptation processes in PSPM-systems, as opposed to contingency-based studies, which assume stability in the fit between context and performance measurement systems.

Apart from these three main theoretical strands, behavioural theories should also be mentioned. They can be important in explaining how certain attitudes and perceptions of decision makers, such as politicians and managers, contribute to particular types of performance measurement use. ter Bogt's work on politicians’ styles of evaluating top managers in Dutch local government organizations (ter Bogt, 2001, 2003) is a notable illustration in this respect. He argues that politicians prefer a facilitating style to an output-constrained or outcome-conscious approach. Politicians who adopt a facilitating style expect their top managers to be supportive to their political superiors, for instance by protecting them from the consequences of unexpected events and by running the organization accordingly.

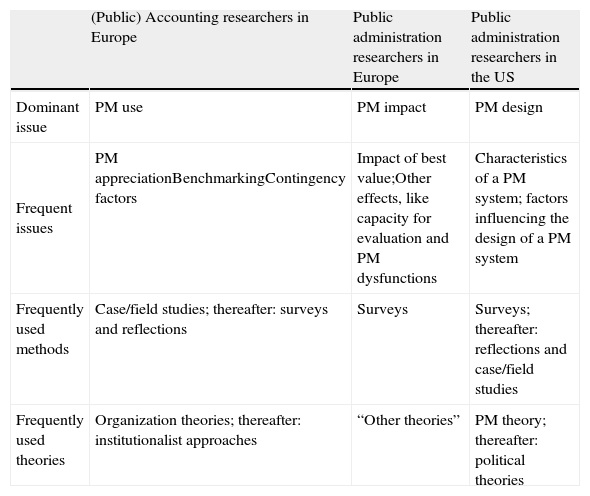

In Europe, organization theories seem to be most influential for explanatory purposes of PSPM-research, followed by economic theories and neo-institutional concepts (van Helden, 2005, p. 108). In the US, the influence of economic theories seems to be stronger (Goddard, 2010, p. 80). Based on the review by van Helden et al. (2008, p. 648) we present an overview of the dominant issues and topics of PSPM-research, the most often applied methods and the dominant theories for explaining and analysing the research results (see Table 4).

Distinctive research patterns of author groups.

| (Public) Accounting researchers in Europe | Public administration researchers in Europe | Public administration researchers in the US | |

| Dominant issue | PM use | PM impact | PM design |

| Frequent issues | PM appreciationBenchmarkingContingency factors | Impact of best value;Other effects, like capacity for evaluation and PM dysfunctions | Characteristics of a PM system; factors influencing the design of a PM system |

| Frequently used methods | Case/field studies; thereafter: surveys and reflections | Surveys | Surveys; thereafter: reflections and case/field studies |

| Frequently used theories | Organization theories; thereafter: institutionalist approaches | “Other theories” | PM theory; thereafter: political theories |

As can be seen, Table 4 distinguishes three groups of authors: European accounting researchers, European public administration researchers and public administration researchers from the US. Because of the limited number of accounting researchers from the US with an interest in public sector performance measurement, this group was not dealt with. The table also highlights the distinctive research patterns for each of the three groups of authors. It shows how three different performance measurement (PM) issues, namely design, use and impact, are associated with topics, methods and theories. These findings correspond to some extent with Goddard's (2010, pp. 82–86) comparison between US and European/Australasian research in public sector accounting. According to him, US research is primarily functionalistic in that it uses large data-bases in combination with quantitative techniques and economic theorizing. In contrast, European/Australasian research is mainly interpretive, which is characterized by the use of qualitative methods and social-science based theories.

5Discussion and issues for future research5.1Changing trendsWe are facing a gradually emerging shift from the examination of performance information design to that of performance information use. Many governmental organizations currently possess PSPM-systems, but their use seems to be problematic or at least limited, which asks for explanations why this is the case (see also Moynihan & Pandey, 2010). Another trend can be seen in the research perspective: while earlier research often was normative, prescribing an economically rational use of performance information (Likierman, 1993), more recent research is more analytical and explanatory. Apart from economic and organizational theories neo-institutional concepts are becoming increasingly influential (Modell, 2009). We further observed two types of studies: one which deals with the specific operationalization of the entire contingency framework (for example Abernethy & Lillis, 2001; Cavalluzzo & Ittner, 2004; Verbeeten, 2008) and the other focussing on the single building blocks or relationships in this framework, for example styles of performance evaluation (ter Bogt, 2001) or the use of performance information for budgeting or rewarding purposes (OECD, 2007).

In our view future research should pursue a thorough investigation of the empirical studies available with the aim of clearly identifying their contradictory results. Subsequently, new theoretical and empirical studies should be initiated to analyse these contested explanations. An example could be to review contingency research on the managerial or political use of performance information by using the framework discussed above, followed by additional empirical work on the contested contingency relationships (for example as in Moynihan & Pandey, 2010; Kroll, 2012, chap. 2).

5.2Using hard data in contingency studies on organizational performanceAs explained in Section 3, contingency-based research links the fit between context and PMS to organizational performance. In many cases, this organizational performance is measured via self-reporting, which means that managers or politicians are asked to express their individual perceptions of the performance of their organization. This way of measuring is disputable due to its subjectivity. A promising future direction for this type of research could be the use of hard data. This type of information could be derived from quantitative methods like Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), which enables the provision of a maximum output generated via any possible combination of inputs, that is, one can construct a so-called production technology frontier or efficiency frontier. According to Vakkuri (2003), DEA decreases the risk of making incorrect assumptions about efficient behaviour, because the efficiency frontier reflects the real facts. Organizations positioned on the efficiency frontier achieve the best possible efficiency score of 100%, serving as a standard based on which the scores of organizations with lower efficiency levels are determined. Vakkuri warns, however, that the efficiency frontier method may produce ambiguous outcomes because the multiple in- and outputs are the result of an optimization procedure which yields the best possible sets of relative priorities. This path of future research combines two apparently unconnected research traditions: on the one hand survey-based studies of the match between the organizational context and the PSPM-system within a number of organizations, and on the other hand relative efficiency scores derived from hard data on multiple in- and outputs representing the factual operationalization of the organizations’ performance (see Naranjo-Gil, Maas, & Hartmann, 2009 for an example).

5.3Challenging the fabrication concept of PSPM-systemsJackson (2011) regards the lack of an adequate conceptualization of the context in which public sector organizations operate as a major gap in the existing body of knowledge of PSPM-research. This gap relates to the overly simple view how public sector organizations are supposed to produce outputs resulting in outcomes. Jackson (2011, p. 16) argues that outcomes often result from co-production of different organizations including clients. ter Bogt et al. (2012) have provided a proposal how the transformation process of complex project-type outputs can be conceptualized. Their conceptualization of co-production concerns projects developed by the focus organization in collaboration with other actors. In addition, because a project is a complex set of interrelated tasks, simple output indicators are insufficient. Instead, extensive information on the nature of the underlying activities and their effects is required. Moreover, this approach also takes into account that certain project outcomes are only observable in the long run, that is, beyond the scope of the annual planning and control cycle.

Another alternative for the simplistic conceptualization of an organization as a fabrication process is to perceive it as an actor within a network of multiple other actors. According to Provan and Milward (2001), network performance is more complicated in the public sector than in the private sector because the user needs of constituent groups are relatively diverse and politicized. Provan and Milward propose a framework for analysing public-sector network performance at three levels of analysis: the community, the network and the service provider level. At the community level networks have to be valued based on criteria such as client access to services, extent of service integration, responsiveness to client needs and costs of services. These criteria are mostly measured at an aggregate level, that is, for the network as a whole.

Agostino (2012) elaborates on the Provan and Milward framework by showing how the performance indicators are designed and used at various levels by an Italian public transportation network. This empirical study gives evidence of the relationship between performance indicators concerning policy making and management. The author concludes that accounting expertise (i.e. knowing how to use numbers) contributes to a more powerful position of knowledgeable participants in the network, but that the availability of performance information may also undermine the trust among the network participants.

Johnsen (2005) questions the hierarchical conception of PSPM-systems even more fundamentally. His main argument is that different stakeholders, such as politicians, managers and the public, often use performance information for strategic purposes, for example to serve some particular interests. Such a type of user behaviour can change the relative power positions of stakeholders, who are considered to be competitors in a political market. Johnsen's (2005) way of reasoning challenges the traditional way of viewing the strategic use of performance information as a negative side-effect of rational behaviour (see also Vakkuri & Pentti, 2006). In a more general sense, the current research seems to be biased towards a mainly economic model of public sector organizations, in which efficiency receives a great deal of attention at the expense of elements like equity and quality of services (van Helden et al., 2012).

5.4Finding inspiration from private sector researchPSPM-research can potentially benefit from studies of performance measurement and management in the private sector. Here are two issues with potential relevance for PSPM-research: target ratcheting and different options for pay-for-performance systems.

Bouwens and Kroos (2011) have examined the concept of target ratcheting. The context is a situation in which managers can earn bonuses when they realize a better performance than required by the performance standard. Target ratcheting then refers to the well-known situation where a performance standard is increased after a period during which a higher performance rate was achieved than the initial performance standard. Bouwens and Kroos argue that managers who establish good performance levels during the first three quarters of a year are inclined to reduce their efforts during the final quarter in order to end the year with a relatively lower rate. The purpose of this decrease in efforts is to avoid an increase of the performance standard for the next year. So there is a trade-off between the current rewards resulting from a favourable performance and future losses related to increased performance standards.

Höppe and Moers (2011) have investigated the reasons why CEO's of big companies make use other types of bonus agreements than the so-called formula-based contract, which includes a formula that links the agent's performance to his/her bonus ex ante. Höppe and Moers distinguish two other types of bonus contracts. The first is a discretionary bonus contract, with which a formula-based contract can be overridden. Such a contract may be especially suitable in circumstances of random shocks in performance that cannot be influenced by the agent. The second is a bonus contract that subjectively attaches weights to various types of performances. This type is particularly appropriate in circumstances where the predictability of the environment is low and where it is more difficult to identify the agent's courses of action and related performance in advance, as implicitly required by a formula-based contract.

Such empirical studies are of potential interest also for PSPM, particularly as pay-for-performance systems have gained more attraction in public sector. For many public sector organizations it is difficult to find appropriate proxies for good performance, which clearly implies that instruments other than formula-based bonus contracts are relevant options, such as discretionary bonus or subjective bonus contracts.

5.5Assessing the body of knowledge of PSPM-researchHow much progress have we made in the last decade in developing a relevant and coherent body of knowledge of public sector performance measurement research? Contingency-based studies can be considered as the predominant type of research on PSPM-systems. Our analysis of this type of research resulted in the following findings. First, across the various contingency-based studies there is only limited consistent evidence of the influence of contingency variables on performance measurement design and use. It seems that only the ability to identify performance information and – to a lesser extent – decision making authority and goal or mission orientation play a role in the reviewed literature. Next, we noticed that too many of the publications under review do not rely on soundly developed theories, which sometimes leads to merely pragmatic or even superficial findings. Moreover, most of these studies are so-called ‘constrained contingency-based’ examinations because the fit between the contingency variables and the PSPM-design and use on the one side is not related to the ultimate organizational performance on the other side. The few studies that do include this relationship, however, all measure organizational performance through self-reporting. The subjectivity of self-reporting brought about our suggestion to use efficiency scores derived from hard data on organizations’ multiple inputs and outputs in the operationalization of organizational performance.

The reviewed studies apply various types of theories to analyse and explain their findings. Economic theory, for example, has been considered as suitable for studying economic advantages of the various types of performance indicators as well as the role of incentives in performance measurement use. Organizational and behavioural theories can be of interest in analysing the reactions of organizations on PSPM-implementation and the impact of attitudes and perceptions of managers and politicians on the use of performance information. Finally, neo-institutional concepts allow to take a closer look on different institutional issues of PSPM, e.g. on the impact of traditions, culture, rules and regulations, actor expectations etc. on the design, implementation, operation and use of PSPM-systems. Neo-institutional studies that focus more clearly on adaptation processes in PSPM-systems are central, whereas contingency-based studies assume stability in the fit between context and performance measurement systems. In conclusion, our meta-review of PSPM-research shows that the body of knowledge in this area has expanded to some degree, but that there are also still numerous unresolved issues which need further investigation.

The authors are grateful to Roland Speklé for his valuable suggestions about a previous draft of this paper.

Broadbent, J., & Guthrie, J. (2008). Public sector to public services: 20 years of “contextual” accounting research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(2), 129–169.

Fryer, K., Antony, J., & Ogden, S. (2009). Performance management in the public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 22(6), 478–498.

Goddard, A. (2010). Contemporary public sector accounting research: An international comparison of journal papers. The British Accounting Review, 42(2), 75–87.

van Helden, G. J. (2005). Researching Public sector transformation: The role of management accounting. Financial Accountability & Management, 21(1), 99–133.

van Helden, G. J., Johnsen, Å., & Vakkuri, J. (2008). Distinctive research patterns on public sector performance measurement of public administration and accounting disciplines. Public Management Review, 10(5), 641–651.

van Helden, G. J., Johnsen, Å., & Vakkuri, J (2012). The Lifecycle approach to performance management: Implications for public management and evaluation. Evaluation, the Journal of Research, Theory and Practice, 18(2), 159–175.

Jackson, P. M. (2011). Governance by numbers: What have we learned over the past 30 years? Public Money & Management, 31(1), 13–26.

Johnsen, Å. (2005). What does 25 years of experience tell us about the state of performance measurement in public policy and management? Public Money and Management, 25(1), 9–17.

Modell, S. (2009). Institutional research on performance measurement and management in the public sector accounting literature; a review and assessment. Financial Accountability & Management, 25(3), 277–303.

Moynihan, D. P., & Pandey, S. K. (2010). The big question for performance management: Why do managers use performance information? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20(4), 849–866.