This paper examines human behavior with regard to the transition from a traditional manufacturing philosophy to the implementation of the lean management philosophy. Diverse reasons for why and how associates resist or embrace change in transitioning from a traditional manufacturing environment to a lean manufacturing environment are explored in a lean management model. Senior-management leadership and intrinsic cost/benefit analyses to change by associates play crucial roles in the successful transformation to a lean environment. Knowledge about the myriad reasons why and how associates resist or embrace change may prove useful to engineering managers who champion a massive transformation in business philosophies.

Much has been published about the independent uses of both the lean philosophy and change management concepts; however, there is scant research on the collaborative use of lean and change management. This is largely attributed to an organization's dedicated emphasis toward the successful application of one concept or the other, but not both simultaneously. This article addresses this limitation by presenting organizational behavior findings in an innovative lean management framework illustrating the why's and how's regarding associates’ resistance to or embracement of change as they actively participate in the transition from a traditional manufacturing philosophy to the implementation of the lean production philosophy.

We experience the paradigm of change in our daily lives, from a simple detour on the way to work to changing entire product lines in a factory setting. Change requires an understanding of why change is required, what changes are being proposed, how change will be implemented, who is impacted, and how they are impacted.

Change is essential in business and a primary focus is on developing lean systems, which places enormous emphasis on effectively streamlining operations. Lean organizations seek ways to eliminate all forms of waste (Alukal, 2006; Elliott, 2004; Liker, 2004; Liker & Hoseus, 2007; Mika, 2007) by eliminating all non-value added activities and their associated costs (Womack & Jones, 2003, 2005; Womack, Jones, & Roos, 1990). Efficiencies can be gained by implementing mistake-proofing methods or devices (Bekowski & Litteral, 2006; Howell, 2010) and process improvement efforts such as reductions in machine setup times (White, Ojha, & Kuo, 2010) and process cycle times (Clarke, 2007; Ocak, 2011), thereby improving process flow throughout the manufacturing concern.

Successful implementation of lean principles and techniques also leads to improvements in quality (Chaneski, 2009; Gupta, 2011; Vandenberg, 2009; Womack & Jones, 2005), on-time delivery (Upadhye, Deshmukh, & Garga, 2010), morale (Gnamm & Neuhaus, 2005; Tiplady, 2010), and corporate profits (Myers, 2010; Vandenberg, 2009).

A 24-month direct observational study was conducted consisting of three manufacturing firms within the Forest Products industry located in the Southeast: a corrugated box manufacturer that produces corrugated shipping containers, inner-packing, and point-of-purchase (POP) displays; a folding-carton manufacturer that produces folding-cartons for playing cards, business cards, fine paper, etc.; and a paper mill sheet-feeder that produces combined board, or corrugated sheet stock, from rolls of linerboard and medium.

2Literature reviewWhereas Drucker (1992) suggests that every organization must build the management of change into its structure, less than half of the change efforts enacted are considered successful by the organizations that are pursuing them and the consultants who are assisting them (Hammer & Champy, 1993; Schiemann, 1992). Some research has been performed on various aspects of human behavior as it pertains to implementing change in an organization; however, scant few publications surfaced when exploring the hows and whys of human behavior as an organization undergoes the massive transformation from traditional manufacturing to lean manufacturing. As with traditional manufacturing, lean manufacturing is an overall business philosophy that everyone in an organization must buy into in order to realize maximum benefits.

Regarding the role of senior leadership, Smeds (1994) suggests that when an organization undergoes change, it needs to manage change as an innovation process whereby the vision, direction, and guidelines for change provided by senior management are the most important top-down managerial tools for implementing change. Leader-follower studies by Dixon (2003) and Ray (2007) show high levels of follower behaviors that correlate with visionary leadership behaviors at higher levels of an organization than at lower levels. Dixon (2009) further suggests a new paradigm of the leadership process, whereby associates are recognized for their situational applications of both leader and follower behaviors. Spear and Bowen (1999) decodified the ‘rules’ that true Toyota Production System thinkers use when designing, operating, or improving their systems into four simple steps: (1) structure every activity; (2) clearly connect every customer and supplier; (3) specify and simplify every flow path; and (4) improve through experimentation at the lowest level possible toward the ideal state. Schaffer (2010) offers four mistakes that leaders keep making that will thwart any change effort: (1) managers fail to set proper expectations; (2) they excuse subordinates from the pursuit of overall goals in lieu of personal, or departmental, goals; (3) executives go along with staff experts and consultants by allowing the experts to introduce and implement change without any measurable deliverables; and (4) management waits while associates over prepare for any change initiative. Stylianou, Pepper, and Mahoney-Phillips (2011) discuss a transformational change in a major global bank whereby leadership focused on centralization and integration of functions across business groups to reduce costs and improve profitability. Overlooked, however, was the long-term impact of the transformation on employees as substantial downsizing and role redundancies resulted from the integration strategy.

A dichotomy exists in the area of communication. As a positive, it is suggested that Toyota is able to change mindsets in their organization by aligning the interests of management with those of the shop floor; that is, by having senior management spending time on the shop floor and communicating how each small individual action is part of the bigger plan and to have evidence that things are really changing with the rank-and-file (Pullen, 2004). To enable change, De Smet, Lavoie, and Hioe (2012) suggests the development of management's “softer” skills that include the ability to keep managers and workers inspired when they feel overwhelmed, to promote collaboration across organizational boundaries, or to help managers embrace change through dialog rather than dictation. Long and Spurlock (2008) suggest maintaining clear, regular communication plans that include regular focus meetings and staff bulletins for internal stakeholders and for external stakeholders to participate in yearly meetings and pilot projects. In both cases, a reciprocal feedback process is used. As a negative, Farris, Van Aken, Doolen, and Worley (2008) discusses the failures associated with a lack of communication relative to Kaizen events in a case study. These failures are the result of an overall lack of confidence by Kaizen team members who were unclear about the goals of the Kaizen event, the team's lacking in representation from a key function which led to a lack of input and buy-in from the function, and limited team decision-making authority when the group initially believed they had complete autonomy to recommend and implement change. In a Midwestern regional healthcare study, Mallak and Lyth (2009) describe the “Corporate Way” as negative and imposing, symbolic of a lack of input from outlying facilities and suggest drawing on the strengths of each system entity, involving each employee, and standardizing essential procedures while allowing for discretion and empowerment at the front line. León and Farris (2011) suggest identifying value from the customer's perspective, emphasizing cross-functional and supplier integration, and concurrent task execution as key drivers toward an effective lean product development process. In a study of construction projects, Chang and Shen (2009) propose a model of coordination that can be used to plan coordination before work begins that addresses with whom to coordinate, by what coordination method is required, and for what duration. Their results indicate that construction projects with good performance used adequate oral or written coordination based mainly on work equivocality (or ambiguity). High-equivocality projects consist of information richness as the key element resulting in more time spent on oral rather than written communication as construction projects increase in complexity. Low-equivocality projects lack information richness, resulting in more time spent on written rather than oral communication.

While many companies believe that reducing fear is an essential component of organizational transformation (Ryan & Oestreich, 1991) because of traditional notions that fear results in dysfunctional behavior, Welbourne (1995) concludes that transformations are far different from routine changes and suggests that retaining and communicating fear is necessary for organizations in order to effect significant and rapid behavioral changes. In a lean product development (LPD) study at Ford Motor Company, Liker and Morgan (2011) suggest integrating people, processes, and tools to drive the LPD transformation change. Having driven, accountable team members was instrumental in developing static product development tools such as (1) body exterior engineering, which is responsible for design, release, and testing of everything outside of the vehicle and (2) stamping engineering, which is the process of design and construction of all tools and dies to manufacture the metal components on the body, to a living high-performance system; that is, assembled body and stamping processes that deliver passenger safety and comfort while providing ride characteristics such as noise and vibration aerodynamics. Amid painful layoffs, resistance to change was met with an ultimatum to get on board or leave.

Regarding the feeling of control: emotions, goals, and other drive states can powerfully influence the manner in which people form judgments, evaluate risks, and make choices under uncertainty (Fessler, Pillsworth, & Flamson, 2004; Finucane, Peters, & Slovic, 2003; Isen, Nygren, & Ashby, 1998; Ketelaar & Au, 2003; Mittal & Ross, 1998). Further, many choices rely on judgments of both potential benefits and potential costs (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Mellers, Schwartz, Ho, & Ritov, 1997). McDougall (1923) implies that outcome judgments can be shaped by fundamental motivations that promote exploration and risk-seeking, on the one hand, and self-protection, on the other. Langer (1975) discusses choice as one of the determinants of “illusion of control,” whereby associates expressed more confidence concerning an outcome when they were allowed to make a choice, even though the outcome of the task was obviously determined by chance factors alone. The act of choosing has a close relationship with both Langer's illusion of control and with perceptions of control and autonomy (Deci, 1975; Hackman & Oldham, 1976). Baughn and Finzel (2009) describe a merger of two governmental offices forced by budget cuts, which precluded consideration of cultural factors such as the effects among the personnel involved and their organizational cultures, resulting in what amounted to a hostile takeover by the dominant culture. The failure of a new strategy or strategic innovation is often due to the inability or resistance of associates to commit to a strategy and adopt the necessary behaviors to accomplish strategic objectives (Heracleous & Barrett, 2001) which leads to strategic misalignment, or individuals failing to engage in behavior that supports the organization's strategic goals (Boswell & Boudreau, 2001). Group-oriented employee programs such as Quality of Work Life and Gainsharing are intended to promote employee participation and quality improvement (Doyle, 1983). A by-product of associate participation is cooperative behavior among associates. For example, quality circles allow associates to share their ideas for improving productivity and quality with other members of the group. Beer, Eisenstat, and Spector (1990) suggests that firms should transform from hierarchical, bureaucratically-driven organizations to task-driven organizations whereby the focused energy for change is on the work itself, not on abstractions such as “participation” or “culture.” Naturally, the primary problem for corporate change is how to promote task-aligned change across many diverse units as opposed to only one unit such as a plant or department. However, they offer a six-step critical path, if you will, to effect change with participation and effective communication as the principal drivers.

Programs such as gainsharing reward cooperation by allowing associates to share equally in the profits (Lawler, 1981). Whereas Tjosvold (1986) provides evidence that rewards given at the group level are more likely to promote sharing and assistance among associates than rewards provided at the individual level, Lawler (1981) suggests that most organizations that implement gainsharing-type programs do so while still maintaining individual incentive systems. According to expectancy value theorists of motivation, who believe that workers are future-oriented in that they form expectations about future events and are reactive in that their behavior is a function of these expectations, it follows that members of work groups are assumed to make predictions regarding the rewards that will be received from group work (Sniezek, May, & Sawyer, 1990). In other words, behavior results from decisions made in order to maximize one's overall expected reward level (Mitchell, 1979).

Heath (1999) suggests that associates hold lay theories which contain extrinsic incentives bias (when associates predict that others are more motivated than themselves by extrinsic incentives such as job security and pay), and intrinsic incentives bias (learning new skills). Associates who use improper lay theories offer inappropriate deals to managers which may hinder organizational change. Locke and Latham (2002) assert that associates must have goals that are clear and challenging in order to motivate high performance. Further, a complex relationship exists between goals and incentives. Whereas the provision of incentives may increase goal commitment (Locke & Latham, 1990), if goals are viewed as impossible, then offering a bonus for goal attainment can lower the motivation to perform (Lee, Locke, & Phan, 1997). Assigning challenging goals perceived as attainable would seem to be ideal because incentives would then increase associates’ commitment toward meeting the challenge. Locke (2004) discusses different strategies for linking goals to monetary incentives such as stretching goals with bonuses for success, employing a continuous scale to reward incremental improvements, and motivating associates by goals but paying for performance.

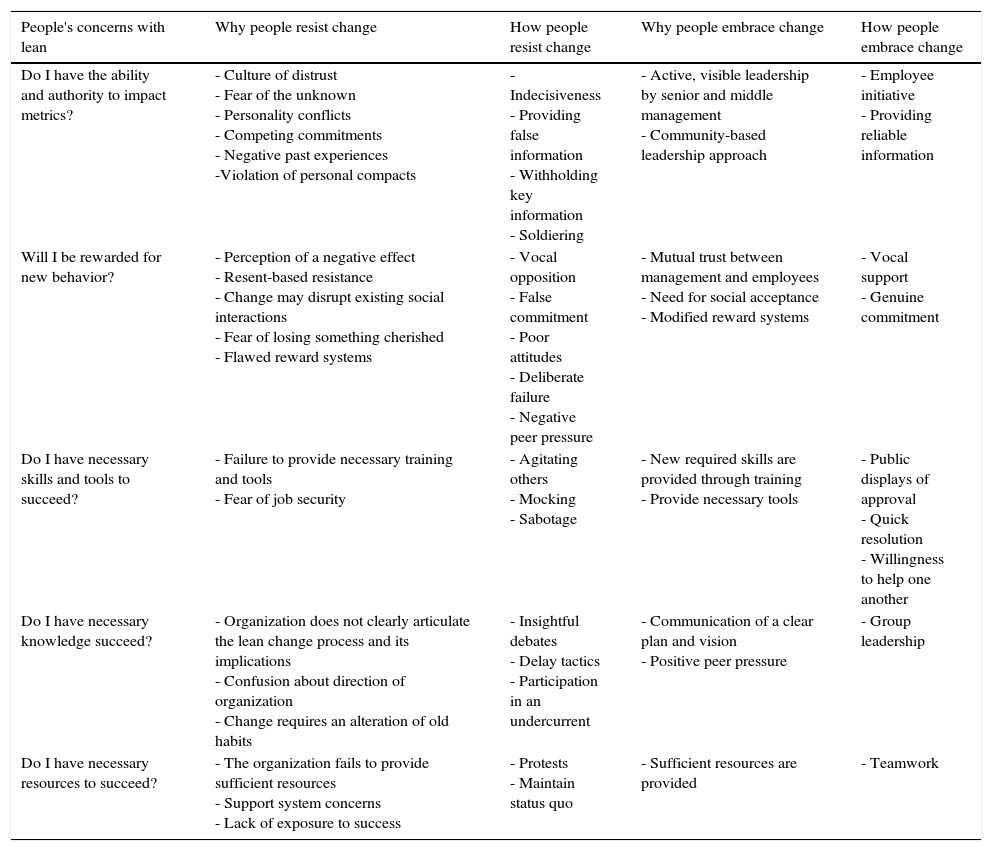

3MethodologyThe methodology used in this study is a direct observational design. All personnel among the three firms in this study were aware that they were being observed and that the researcher's observations were being documented for research use. The data obtained reflect random eyewitness accounts of behavioral outcomes to change initiatives and the relative frequencies of each outcome documented in a spreadsheet. The data include date, individual(s) affected, change mandate, and outcome. Behavioral outcomes were divided into two primary categories: resistance or acceptance. Each category was further decomposed into “why” and “how”; for example, why someone resisted change and how he/she resisted it. Hence, the outline of this paper includes sections for each of the four principal areas of interest: Why people resist change, How people resist change, Why people embrace change, and How people embrace change. Embedded within each section are research examples that address each of the five general concerns that people have with lean implementation in the lean management framework (Table 1).

Lean management framework.

| People's concerns with lean | Why people resist change | How people resist change | Why people embrace change | How people embrace change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do I have the ability and authority to impact metrics? | - Culture of distrust - Fear of the unknown - Personality conflicts - Competing commitments - Negative past experiences -Violation of personal compacts | - Indecisiveness - Providing false information - Withholding key information - Soldiering | - Active, visible leadership by senior and middle management - Community-based leadership approach | - Employee initiative - Providing reliable information |

| Will I be rewarded for new behavior? | - Perception of a negative effect - Resent-based resistance - Change may disrupt existing social interactions - Fear of losing something cherished - Flawed reward systems | - Vocal opposition - False commitment - Poor attitudes - Deliberate failure - Negative peer pressure | - Mutual trust between management and employees - Need for social acceptance - Modified reward systems | - Vocal support - Genuine commitment |

| Do I have necessary skills and tools to succeed? | - Failure to provide necessary training and tools - Fear of job security | - Agitating others - Mocking - Sabotage | - New required skills are provided through training - Provide necessary tools | - Public displays of approval - Quick resolution - Willingness to help one another |

| Do I have necessary knowledge succeed? | - Organization does not clearly articulate the lean change process and its implications - Confusion about direction of organization - Change requires an alteration of old habits | - Insightful debates - Delay tactics - Participation in an undercurrent | - Communication of a clear plan and vision - Positive peer pressure | - Group leadership |

| Do I have necessary resources to succeed? | - The organization fails to provide sufficient resources - Support system concerns - Lack of exposure to success | - Protests - Maintain status quo | - Sufficient resources are provided | - Teamwork |

Once senior management commits to leading and funding the lean transformation, an organization's lean journey enters a “make-or-break” transitional phase for its people. It is at this critical turning point that people either embrace the new business philosophy by choosing to willingly participate in the lean change paradigm or demonstrate resistance to the new philosophy.

Data from this empirical study was documented through the observance of the interactions and resultant behavioral outcomes to change initiatives among people to management in undergoing the transformation to lean. Active observance was conducted by freely walking around throughout the entire facilities of the three firms in this study. The analysis consists of discriminating the more prevalent random behavioral outcomes relative to less prevalent random behavioral outcomes by noting the relative frequencies for each outcome. The more prevalent behavioral outcomes appear in the construction of the lean management framework in Table 1, which details myriad reasons for why and how people resist or embrace the lean philosophy, which will be examined in subsequent sections.

3.2Why people resist changePeople may resist change because they question their ability and authority to impact lean metrics and this occurs for a variety of reasons. The following examples include the prevalence of a culture of distrust, fear of the unknown, personality conflicts, demonstrating competing commitments, negative past experiences, and a violation of personal compacts.

3.2.1Do I have the ability and authority to impact metrics?- 1.

Culture of distrust. In a culture where people are dubious of the abilities or motives of management, any proposed change effort by management is likely to be met with resistance – whether active or passive. Unless the change effort and its implications are clearly communicated and people are convinced that their best interests are in mind, they are unlikely to embrace the change initiative. If, for example, (1) operators in a corrugated box plant are instructed to print their initials in a minor bottom flap, where it is traced back to the operator and a reward such as plant-wide recognition or a free lunch for a job well done may be given or (2) in a culture of distrust, the operator may view this mandate as a means to lay blame and be reprimanded if a customer complaint traces the production run back to her.

- 2.

Fear of the unknown. Even when people are in accord with management that change is necessary, a lack of clarity or familiarity with the unknown creates a sense of angst or trepidation for many people. Beyond their comfort zone, people sometimes envision imaginary obstacles without giving the proposed change the slightest chance for success. One way to soothe feelings of uncertainty is for management to communicate a clear vision of the change initiative including what the proposed change encompasses, who is affected by the change process, and its potential benefits.

- 3.

Personality conflicts. No matter how logical the lean change effort is for the organization, it is doomed for failure when a personality conflict exists between the lean champion and the organization's employees. Sometimes in order to effect change and move forward, disenchanted employees reluctantly become casualties in the workforce.

- 4.

Competing commitments. Many people hold on to strong internal beliefs about themselves and the world around them. These beliefs are so imbued that Kegan and Lahey (2001) refer to these “big assumptions” as a means for putting the world as they see it into a sort of systematic order that makes perfect sense, such as when production management resists the flexibility of accommodating shorter lead times by running smaller batch sizes in deference to traditional large production runs to achieve production efficiency. Conversely, these assumptions, or hidden commitments, can also convey a way in which their view of the world is in a state of chaos. When people feel so deeply that the lean change paradigm is doomed for failure, they will naturally resist, rather than challenge, any kind of dedicated effort. Only when these big assumptions are discovered does irrational behavior become sensible.

- 5.

Negative past experiences. Negative past experiences can leave people with a feeling that any future changes will do more damage than good. In other words, people may feel that change in the status quo will result in an entirely new set of problems with which to contend. For example, when previous change efforts were handled poorly or when desired outcomes were not achieved, a sense of apprehension regarding any future change effort is understandable. However, acknowledgment of a previous failure is not a perfunctory outcome for future changes.

- 6.

Violation of personal compacts. Strebel (1996) defines “personal compacts” as the fundamental relationship between employees and management characterized by mutual obligations and commitments. A personal compact represents an implied contract that, when altered by change, upsets the balance of communal understanding and may lead to associate resistance.

People may demonstrate uncertainty toward change due to perceived negative effects, resent-based resistance behavior, the possible disruption of existing social interactions, a fear of giving up something they cherish, and flawed reward systems.

- 1.

The individual (or group) perceives a negative effect. Change reflects a difference in the status quo. Individuals innately compute how change will impact them even before the change takes place. If the individual perceives a negative effect, such as incurring additional job responsibilities at the same pay rate, then he or she will likely be resistant to change. If, however, the individual perceives a positive effect, such as a promotion along with a raise or job expansion, then he or she will likely embrace change.

- 2.

Resent-based resistance. Folger and Skarlicki (1999) suggest that resent-based resistance behavior is a direct result of recalcitrant employees who perceive an inequity in the change effort. Such behavior ranges from non-discriminate actions, such as agreeing with a proposed change and then masking any support effort, to sabotage within the organization. The offenders subjectively justify their actions as a means for getting even for any perceived disservice caused by the change effort such as being overlooked for a job promotion in favor of someone with less experience or qualifications.

- 3.

Change may disrupt existing social interactions. If an individual is transferred to a different department and removed from current social interactions, he or she may be resistant to such a change. As Abraham Maslow's pioneering work in motivation theory revealed, once an individual's physiological and safety needs are satisfied, needs such as love and self-esteem which are satisfied through social interactions become important motivators for success (Maslow, 1943). This often occurs when employees are selected for work cells because of their specialized skill set and efficiency. Once removed from the general workforce population, employees in isolated work cells may feel a loss in the sense of “belongingness” or “acceptance,” which may result in substandard quality or production output.

- 4.

Fear of losing something cherished. Familiarity breeds a sense of dominion in the workplace. People who routinely perform tasks are adept at knowing what works and what does not. A change in familiarity leads to a compromise – is what the individual must forsake worth the risk of learning and doing something different? In an innate cost–benefit analysis, if individuals predetermine that they will lose more than they will gain by embracing the lean change initiative, they will probably resist the change. The more security, status, and control provided to individuals by accommodating the proposed change, the more inclined they will become in accepting the lean philosophy.

- 5.

Flawed reward systems. Resistance to change is likely to occur when management rewards behavior they are trying to discourage while neglecting to reward desired behavior (Kerr, 1975). For example, if raises are administered across the board without individual consideration for compliance to change initiatives, there is little incentive for noncompliant workers to embrace change.

Resistance to lean change efforts may occur when the organization fails to provide the necessary skills or tools of success in the new business philosophy leading to a feeling of inadequacy or a fear of job security among employees.

- 1.

Failure to provide the necessary training and tools for success. The lack of a structured training program to accompany traditional “on-the-job” training inhibits the learning of new skill sets. On the one hand, learning from an experienced professional reveals invaluable hidden knowledge obtained by “working in the trenches” over the years but, on the other hand, old habits are learned where more efficient methods could be utilized with structured training. Further, without benefit of proper hand tools and materials, operators and crew members will struggle to reduce setup times or make proper machine adjustments by using broken tools or the wrong tools because the correct tools are either missing or had never been provided.

- 2.

Fear of job security. Learning a new skill, such as setup reduction techniques or obtaining knowledge about a process by monitoring changes, or shifts, using control charts, may be required. The absence of newly acquired skills may lead an employee to feel a sense of apprehension regarding her future employment with the organization.

The new lean business philosophy will require employees to acquire heightened knowledge in order to ensure a sustainable lean transformation. As a result, employees may resist change if senior management does not clearly communicate the lean change process and its implications, if confusion about the direction of the organizations exists, or if people refuse to alter their old habits to accommodate change.

- 1.

The organization does not clearly articulate the lean change process and its implications. When little or no communication about the need to adopt the lean philosophy and its potential benefits are shared with employees, one should anticipate a great deal of resistance in deference to maintaining the status quo. Moreover, when management mandates a transition to lean and genuine concerns are ignored, the presence of controlled restraint may exist in the workplace. People want to feel as though their experience and input provides value to the organization. When denied opportunities to participate in the change process from an intellectual standpoint and without a clear understanding of its implications, employees will likely resist the change effort simply because it was handled poorly by management from the onset.

- 2.

Confusion about the direction of the organization. People tend to feel lost when provided vague information regarding a new direction for the organization. Understandably, senior management must articulate a well-conceived plan and a clear vision of where the organization is headed in order for the change initiative to gain acceptance in the workplace.

- 3.

Change requires an alteration of old habits. When people become accustomed to doing things a certain way, the anticipation of change for many becomes unsettling and stressful. For example, a fundamental change from a traditional reactive maintenance approach, whereby maintenance activities are triggered by machine breakdowns or other process failures, to a proactive lean maintenance approach, where scheduled PM's are the norm, demonstrates an alteration of old habits. Altering one's familiarity with regard to job responsibilities, work methods, or surroundings may lead to anxiety or a feeling of inadequacy.

Lindeke, Wyrick, and Chen (2009) suggests bringing together individuals with unique characteristics, such as self-confidence, attraction to complexity, willingness to take risks, and passionate about ideas and change, from different backgrounds, departments, and experiences, for a temporary period, to an independent organization known as a temporal think tank™. At the temporal think tank™, interactions are facilitated, innovative ideas are cultivated in a unified culture, and then individuals return to their organizations prepared to offer new, fresh ideas with a goal of spurring creativity and innovation among their colleagues and driving the organization forward.

3.2.5Do I have the necessary resources to succeed?Typically, people will resist change if the organization fails to provide sufficient resources to effect change, if there are support system concerns, or if management neglects to share success stories with the workforce.

- 1.

The organization fails to provide sufficient resources. Once the lean change initiative has been communicated, failure is imminent if sufficient resources such as funding, manpower, training, time, and tools are not provided. For example, an emphasis on setup time reduction is doomed for failure if sufficient time and resources are not allocated for videotaping the setup process and converting internal tasks to external tasks, where appropriate, and allowing sufficient time to brainstorm and discuss setup time reduction efforts.

- 2.

Support system concerns. When employees are required to learn new skills, work in new groups (or shifts) with unfamiliar people, report to a new supervisor, or are given new assignments, the fear of trying something new may prove quite intimidating. Gradually, as people become settled in their new roles, support systems will be formed to provide individuals with the confidence they need to succeed without apprehension.

- 3.

Lack of exposure to success. A lack of feedback can work to the detriment of any momentum gained simply because people are uninformed about lean success stories within the organization. This impropriety can imbibe the lifeblood out of any enthusiasm attained in the workforce. One organization posted lean success stories on the Employee Bulletin Board that included team member photos and a brief description of the issue that was addressed (i.e., reducing machine setup times from an average of 35min to an average of 23min). In addition, the improvement methodology and corresponding results were provided and compared to the traditional way of setting up the machinery. Finally, a new work standard was established and its anticipated positive bottom-line impact was shared.

People resist change in both overt and covert ways. An understanding of the present work culture is crucial in order to understand the true acceptance level of change. The manner in which people resist change when their ability and authority to impact metrics is ambiguous and includes indecisiveness, providing false information, withholding key information, and soldiering.

3.3.1Do I have the ability and authority to impact metrics?- 1.

Indecisiveness. The absence of a clear vision may lead to indecision on behalf of people with regard to rejecting or accepting the lean change paradigm. This indecision impedes the organization's growth momentum because it lacks 100% commitment from its workforce. In weighing the cost/benefits of change, employees lacking a full comprehension of why the lean change process is necessary and its potential benefits may exhibit an unwillingness to vocally support the change simply due to their fear of the unknown as the organization ventures into uncharted waters.

- 2.

Providing false information. The provision of false information is another indication of resistance to change. For example, falsifying data on a control chart to make a production process appear stable and in-control has a very detrimental effect in the workplace. Not only is the data misleading by providing a false sense of security that the production process is performing satisfactorily; once discovered, it naturally breeds a sense of distrust between management and the people responsible for falsifying the data.

- 3.

Withholding key information. Withholding key information relevant to the proposed change negatively impacts the ability to make good decisions. For example, if a maintenance mechanic is charged with re-wiring an out-of-service piece of equipment for future sale as part of a 5s initiative, but has no desire to do so due its wiring complexity or because it may require overtime, the mechanic may dispose of (or conceal) the electrical schematics for the equipment, thus rendering it nearly impossible to re-wire.

- 4.

Soldiering. Frederick Taylor's concept of “soldiering” refers to when employers restrict increases in productivity by refusing to give adequate compensation (Taylor, 1916). For example, people may decide to work at a slower pace than normal in retaliation for being denied a higher pay rate for the performance of more difficult tasks. The setup process may deliberately take longer than usual, the machine may run at a slower rate than projected, and the operator may purposely neglect to make necessary machine adjustments during a production run.

If people are inadequately rewarded for learning and adopting new behavior that is required of lean, they may be apt to resist change by offering vocal opposition, giving a false commitment, adopting poor attitudes, demonstrating deliberate associate failure, or through negative peer pressure.

- 1.

Vocal opposition. Vocal opposition to change includes arguing, talking back, or sarcasm rather than engaging in a non-threatening and respectful verbal disagreement. This behavior can escalate to verbal abuse or violence if not quickly diffused.

- 2.

False commitment. When people appear to accept the lean paradigm, yet bridle any effort to help implement lean, they are demonstrating a false commitment to the lean effort. For example, lean maintenance takes a proactive approach to keeping machinery and equipment operating at peak efficiency. Preventive maintenance activities (PM's) are performed on a scheduled periodic basis and involve actions such as changing or adding lubricants like oil or hydraulic fluid, inspecting parts for wear or damage leading to repair or replace decisions. High operational availability and high reliability of equipment are two primary goals of lean maintenance. If a mechanic feigns going through the motions of greasing all the alemites on a machine but, in actuality, purposely skips numerous alemites, then he is demonstrating a false commitment to the overall lean effort.

- 3.

Poor attitudes. Influential employees who manifest poor attitudes toward the lean change initiative have a destructive effect in the work place. Closed-minded remarks, such as “We’ve tried that before and it doesn’t work” or “This is the way we’ve always done it” create obstacles toward achieving acceptance. This is not always done by 20- or 30-year employees who stubbornly refuse to change their ways. Obstinance is age-indiscriminant. If permitted to continue by management inaction, poor attitudes can infect the entire workforce and result in a devastating, cancerous effect on employee morale, quality, and productivity.

- 4.

Deliberate associate failure. Deliberate failure occurs when employees purposely establish failure mechanisms such as failing to make proper known adjustments, failing to properly inspect products they produce, and improperly training associates. This show of non-violent resistance is akin to sabotage.

- 5.

Negative peer pressure. Negative peer pressure, through the denial of social acceptance among work groups, undermines the change initiative. If only one individual, for example, goes against the grain and ascribes to the lean change paradigm when the prevailing work culture is dead-set against it for any number of reasons, the lone individual will very likely be ostracized by his/her co-workers by being spoken to harshly, by being given the cold shoulder, or a host of other negative peer pressure tactics. He or she may also be called by offensive labels rather than by name. An individual's true character, grit, and will are severely challenged by the sudden denial of social acceptance. For many, it eventually proves too stressful to continue in this manner before finally succumbing to the group norm.

Active resistance may come in the form of agitating others and mocking. Passive resistance may occur in the form of sabotage.

- 1.

Agitating others. The agitation of others by ridiculing, teasing, or goading is a clear indication of resistance to change. This resistance tactic serves to not only antagonize the intended one(s), but also to enlist resistance support from others. Negative name-calling of fellow employees or members of management can obviously escalate into more aggressive or even violent behavior, as some people have a short threshold for cruel agitation by others.

- 2.

Mocking. Mocking refers to making a mockery of the lean champion and the lean change effort itself. Depending on the work culture, the mocking agent may be perceived as either a hero or a fool by fellow employees. Whereas in a negative work culture, the mocking agent becomes a hero as the designated voice of the work culture's resistance to change (and also a thorn in the side of management), in a positive work culture, employees view the mocking agent as the “bad apple” amongst them.

- 3.

Sabotage. Sabotage refers to the deliberate subversive interference of machinery, people, or processes that may lead to injury, or worse. This can be accomplished by poorly training fellow employees such as giving confusing instructions, purposely teaching procedures out-of-sequence, skipping essential steps, belittling fellow employees as they try to learn, etc. Furthermore, neglecting operator maintenance, abusing machinery and equipment through horseplay, deliberately breaking, bending, or twisting parts, overloading equipment capacities and so on are examples of sabotage.

When people lack the necessary knowledge to succeed in a lean environment, they may positively resist change by engaging in an insightful debate to gain a better understanding of the change process or negatively resist change by exercising delay tactics or participating in a workplace undercurrent.

- 1.

Insightful debates. Management should exercise caution when employees initially resist the lean change effort. Rather than assuming that people are being disrespectful when they disagree with lean change initiatives, leaders should take time to listen to employee concerns. These concerns may prove instrumental in achieving a better understanding by both parties regarding the proposed change and its implications on behalf of the organization. Employees may offer an insightful perspective based on experience or knowledge that had not previously been considered.

- 2.

Delay tactics. Exercising delay tactics, such as requesting additional data, requesting more employees, or requesting task forces to further explore the feasibility of the proposed change is a clear indication of resistance to change.

- 3.

Participation in an undercurrent. Threatened by insufficient knowledge to succeed in the lean paradigm, some people may resort to participating in a workplace undercurrent whose purpose is to covertly undermine the lean transition. For example, the lean principle of production leveling is designed to smooth the flow of production and eliminate bottlenecks that cripple production by restricting output. However, if employees deliberately create new bottlenecks, thereby negating the benefits of leveling the production flow, any gains achieved will be lost. More importantly, the confidence of production employees in the failure of this aspect of the lean philosophy may be irretrievably lost as well.

People may use a form of protest or attempt to maintain the status quo as a means for resisting the lean change mandate.

- 1.

Protests. A protest such as a strike is an obvious display of resistance to the lean change initiative much like workers who go on strike to protest a lack of pay increase or job benefits. Protests serve as a vehicle to gain attention; however, their levels of success are debatable.

- 2.

Maintain status quo. People may choose to maintain the status quo because they either do not know how to change, are incapable of change, or are simply demonstrating an unwillingness to change. Naturally, they risk their job security by doing so.

What can management do to overcome peoples’ resistance to change? An understanding of why people embrace change may succor the lean initiative. People are likely to embrace the lean change paradigm when associates perceive active involvement by senior and middle managers and when a community-based leadership approach is employed.

3.4.1Do I have the ability and authority to impact metrics?- 1.

Active, visible leadership by senior and middle management. Active involvement by senior and middle management accelerates the acceptance of change. Only when senior and middle management become visible on a daily basis and engage with people by conversing in the language of lean and speaking familiarly about current Kaizen events will employees gain a sense that management is “walking the walk” rather than merely “talking the talk.”

- 2.

Community-based leadership approach. Organizations may also consider adopting Mary Parker Follett's community-based leadership approach of “power with, rather than power over” (Follett, 1924) when transitioning to lean. Facilitated by and through direct personal relationships, Follett believed that the best leaders know how to make their followers feel empowered, rather than followers merely acknowledging leadership power. Soliciting and listening to employee input with regard to the implementation of lean initiatives increases the likelihood of acceptance. Employee knowledge is an often untapped; yet extremely valuable, organizational resource.

When management takes appropriate action to reward employees for lean successes, they are more apt to embrace lean change initiatives. Benefits include developing a mutual trust between management and employees, recognizing and abetting the need for social acceptance, and modifying reward systems.

- 1.

Mutual trust between management and associates. Senior management must lead the change effort by communicating their expectations and holding people accountable for success. Moreover, workers are more likely to accept a proposed change when senior and middle management demonstrates genuine commitment. This can be accomplished in part by interacting with employees and asking pertinent questions relative to change initiatives. Mutual trust between management and employees is imperative toward successfully implementing change initiatives.

- 2.

Need for social acceptance. Change may involve the reassignment of workers which may occur when employees change work shifts, job assignments, or are reassigned to different departments or work cells. It is essential for management to recognize the development of new social interactions and the need for people to feel accepted in their new assignments. Maslow (1943) and Mayo (1945) clearly emphasize the motivational need for social interaction through human relationships in order to succeed in the workplace.

- 3.

Modified reward systems. Reward systems must be consistent with performance. If newly acquired skills and knowledge are required as part of the lean change process, then rewarding people for embracing change initiatives enhances its likelihood of permanent acceptance in the workplace. Employees in the case study routinely demonstrate motivation and acceptance to change through some form of incentive – be it a pay increase, promotion, extra privileges such as time off with pay, longer smoke breaks, less daunting tasks to perform, etc.

The provision of necessary training and tools to accomplish lean objectives advances people's acceptance of change.

- 1.

New required skills are provided through training. When people begin to see the investment of resources devoted to educating the workforce about new lean techniques, they are much more inclined to embrace the change initiative.

- 2.

Providing necessary tools. The provision of necessary tools is critical toward accomplishing lean objectives with minimal difficulty. Books, schematics, videos, and hands-on training by a lean expert in allocated training sessions ease the acquisition of learning new skills without the guilty pressures of getting back on the shop floor.

People are likely to embrace change if they acquire sufficient knowledge about the basic principles of lean in order to succeed. Communication of a clear vision and positive peer pressure are vital elements that enhance the acceptance level of change.

- 1.

Communication of a clear plan and vision. Senior management can help overcome resistance to change by communicating a clear vision of the change initiative. This involves articulating what changes are forthcoming, why change is necessary, who is involved, and how the workers and organization will benefit as a result. The new plan and vision could also be incorporated into the organization's mission statement.

- 2.

Positive peer pressure. Positive peer pressure is a great motivational technique to get fellow employees to embrace the lean change paradigm because few people want to be known as “the problem child.” Peer pressure helps individuals overcome any hesitancy felt during the transition to lean. Sometimes, all people need is a little nudge – be it vocal encouragement by a fellow employee or seeing someone they favor going along with carrying out a lean initiative – to change their mindset from ‘undecided’ to ‘advocate.’

When necessary resources to accomplish any lean objective are provided, it becomes more likely that people will embrace the change initiative.

- 1.

Sufficient resources are provided. People are more likely to embrace the change to lean if sufficient resources such as a qualified lean expert, funding, time, people, training, and materials are provided. This “investment” enables people the proper training and senior-level management support and commitment that is essential to successfully implement a major philosophical business transformation.

When people buy into a new change paradigm, they embrace it by demonstrating good-faith efforts and by providing reliable information.

3.5.1Do I have the ability and authority to impact metrics?- 1.

Employee initiative. A clear indication that people embrace change is when they assume the initiative to make lean changes happen rather than waiting to be told to do so. For example, when people make 5s a routine part of their workday or when they take the initiative to post clearly marked visual controls such as warning signs (i.e., hard hat area or hearing protection required or designated pedestrian walkways), they are at once embracing the lean change paradigm as well as making the workplace more organized and safe.

- 2.

Providing reliable information. Providing reliable information to quickly resolve issues demonstrates acceptance of the lean change paradigm. This occurs when people disclose complete information regarding an issue or an event rather than divulging only what they want management to know. For example, if operator negligence results in a bad production run because he was busy surfing the web on his iPod or Blackberry instead of monitoring the production process, it needs to be identified and addressed as the root cause of the problem rather than blaming poor quality outputs on out-of-spec inputs entering the production process.

People typically express their acceptance of change through vocal support and by showing a genuine commitment to lean change initiatives.

- 1.

Vocal support. Once mutual trust and understanding are reached concerning the required change effort and corresponding reward system, a show of vocal support publicly demonstrates acceptance by employees. Whether stemming from a rallying cry by a peer group leader or a simple verbal exchange of encouragement among associates on the factory floor or work cell, vocal employees can influence the acceptance of any change initiative.

- 2.

Genuine commitment. Commitment to the lean philosophy implies buying into or looking for ways to improve the manufacturing process. One way to accomplish this during a Kaizen blitz, for example, is to expediently implement the most prudent process improvement idea within the designated 2–5 day Kaizen event period.

Once people are provided with the necessary education and tools to carry out lean initiatives, their acceptance of the lean philosophy can be overtly demonstrated with public displays of approval and by seeking quick resolutions to issues through a willingness to help one another.

- 1.

Public displays of approval. Public displays such as posters or banners in the workplace that are used to reinforce awareness are a great motivational tool. They draw attention and stress the lean message without being overbearing or confrontational.

- 2.

Quick resolution. When people embrace change, they tend to seek quick resolutions to situations rather than resorting to delay tactics. In proactive mode, employees tend to want to resolve problems or issues and move on rather than prolonging a problem with no hope of a resolution in sight.

- 3.

Willingness to help one another. In keeping with the Kaizen principle, a willingness to help one another is an open display of alacrity for the lean change effort. This demonstrates an understanding and agreement of potential benefits to be realized with cooperative effort versus a filibuster that accomplishes nothing.

A strong show of acceptance of the lean paradigm is when group leaders fervently participate in implementing the lean philosophy in the workplace.

- 1.

Group leadership. Group leaders can demonstrate acceptance of change initiatives by enthusiastically participating in the change movement. By taking the lead role in learning the new philosophy and applying it in the workplace, those who follow will likely be sufficiently influenced to embrace the lean philosophy.

Nothing demonstrates the acceptance of change better than a manifestation of teamwork.

- 1.

Teamwork. This is demonstrated when people work together toward the achievement of common lean objectives without bickering, arguing, or any sort of pettiness. For example, synergistic multi-person work cells, where roles and responsibilities are clearly defined and understood, that work in harmony are much more likely to achieve production, quality, and delivery goals than by working in a dysfunctional work cell.

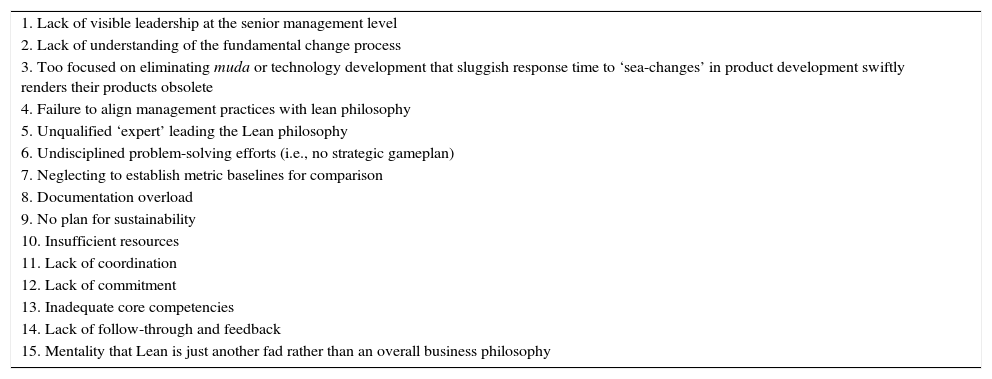

Although many organizations begin their lean journey in great anticipation that lean is the panacea for all of their production and efficiency woes, current literature reveals that many organizations quickly abandon their lean journey due to a variety of reasons, whether from an inadequate understanding of the current state of the organization (Flinchbaugh, 2006; Pawley & Flinchbaugh, 2006) or the overall lean philosophy and the transformation process at the executive level (Boyer & Sovilla, 2003; Cua, McKone, & Schroeder, 2001; Herron & Braiden, 2007; Hyotylainen, 1998; Wilson, 2004). Lean failures may result from being so focused on eliminating muda (Chen, Lindeke, & Wyrick, 2010) or technology development that sluggish response time to disruptive innovations, such as a ‘sea-change’ in competitors’ products, swiftly renders their products obsolete (Christensen, 2003). Additional reasons for abandoning lean include a failure to realize that lean is a journey rather than a single event (Kessler, 2006; Shah & Ward, 2003; Wheelwright, 1984) or a fundamental business philosophy rather than just another program that will run its course and die (Bhasin, 2006; Bouck, 2003; Knight, 2007; Miller & Roth, 1994).

The authors’ research suggests myriad reasons why the lean philosophy fails in many organizations and is provided in Table 2. Granted, a number of additional factors could be attributed to the failure of lean initiatives; however, the authors believe the reasons in Table 2 reflect the primary contributing factors. And yet, the list appears simplistic in the sense that the list does not consider precedence relationships and interdependency, or interaction relationships. While it may be argued that lack of senior management direction results in failure to successfully adopt the lean philosophy in organizations, it may also be argued that a great many organizational failures with regard to lean are attributed to an inability to sustain the lean momentum once it is successfully launched.

Why lean fails.

| 1. Lack of visible leadership at the senior management level |

| 2. Lack of understanding of the fundamental change process |

| 3. Too focused on eliminating muda or technology development that sluggish response time to ‘sea-changes’ in product development swiftly renders their products obsolete |

| 4. Failure to align management practices with lean philosophy |

| 5. Unqualified ‘expert’ leading the Lean philosophy |

| 6. Undisciplined problem-solving efforts (i.e., no strategic gameplan) |

| 7. Neglecting to establish metric baselines for comparison |

| 8. Documentation overload |

| 9. No plan for sustainability |

| 10. Insufficient resources |

| 11. Lack of coordination |

| 12. Lack of commitment |

| 13. Inadequate core competencies |

| 14. Lack of follow-through and feedback |

| 15. Mentality that Lean is just another fad rather than an overall business philosophy |

One research limitation is that the research findings in this paper are the result of a 24-month direct observational study in three different industries within the umbrella Forest Products industry. Thus, the findings are representative of a unique sample population and may not be generalized into other industries or the industrial population as a whole. A second research limitation is that the researcher's only documented what they witnessed in person. Many situations arose during the study that were not captured by the researcher's because they occurred without the researcher's presence and, therefore, these accounts were excluded from the data collection. Since the data collected reflect only direct observations of behavioral outcomes, a third research limitation is that cause–effect relationships cannot be determined. A fourth limitation to this study is that people who are knowingly observed, even for research-only purposes, may alter their behavior to some degree, thereby potentially skewing the observed data.

6Conclusions and implications for engineering managersThe paradigm of change presents organizations with a conundrum. While it may be difficult to dislodge an organization from familiar, traditional manufacturing practices, it may be compulsory for the organization's survival. Resistance to change in adopting the lean philosophy inhibits an organization from expediently moving forward with their vision. From a practical standpoint, for engineering managers, it can lead to problems in productivity, quality, morale, and, ultimately, profitability which impacts the organization's ability to survive. This, in turn, may lead to a deleterious effect on the engineering manager's responsibilities for coordinating and directing projects, making detailed plans for accomplishing goals, overseeing the development and maintenance of staff competence and directing the overall integration of activities. Active, visible involvement by senior and middle management should be the motivating catalyst for lean organizational change. Leaders must also provide the requisite commitment and blueprint for a successful transformation to lean.

Articulation of the lean plan and vision should coincide with an open discussion concerning why change is necessary in order for the organization to move forward. The more informed people become regarding the motives behind the decision to implement lean, the more likely they are to embrace the change mandate. Moreover, an explanation of the alternative to change such as a loss of market share or loss of job security may provide enough incentive to sway any pessimists into accepting the new business philosophy.

Sufficient resources such as funding, time, people, training, and materials must be allocated to educate the workforce in the fundamentals of lean. Once implementation has begun and successes realized, senior management should routinely provide feedback to reinforce associates that their efforts play a crucial role toward the organization's growth. Periodic feedback fortifies the lean plan and vision articulated by senior management. Providing associates with the necessary education, proper tools, and support system to learn and implement lean principles will help minimize any apprehension felt by those who feel hesitant about the rationale for change.

Changing an organization's overall business philosophy is a bold, but risky, proposition. In the absence of any guarantees that the lean change process will be successful, associates will only participate if they feel that the risks of moving in a new direction far outweigh the risks of maintaining the status quo. Providing legitimate examples of lean success stories with numbers to magnify its impact in other organizations will help gain the acceptance of skeptics.

Acknowledgment that pursuing a new direction is a difficult endeavor for any organization may help soothe ambivalent feelings toward the transition to lean. Senior management must also show patience and recognize that people need time to adjust to changes, particularly since change impels them from their familiar comfort zones. Rewarding associates for the achievement of lean objectives through compensation or recognition is a key motivating factor toward the sustainability of lean within the organization.

From a theoretical standpoint, engineering managers must be cognizant of the changes that organizational behavior contributes toward the feasibility of adopting a new product design, as well as the installation, testing, operation, maintenance, and repair of facilities and equipment when transitioning from a traditional manufacturing environment to a lean manufacturing environment. Moreover, the ability to recognize behavioral changes – both positive and negative – aids the practicing engineering manager to quickly adapt to associates’ acceptance or resistance of change management initiatives in order to successfully transition to a lean environment.

People, largely being creatures of habit, grow into comfort zones that, undoubtedly, will be upset when change is introduced, or worse, mandated by management. However, change is a constant aspect of life in a lean environment. We necessarily become adaptable to change.