Suicide attempts represent a public health concern. The objective of this study is to describe the clinical characteristics of patients visiting an emergency room for a suicide attempt and included in a suicide prevention program, the Catalonia Suicide Risk Code (CSRC), particularly focusing on the follow-up evaluations.

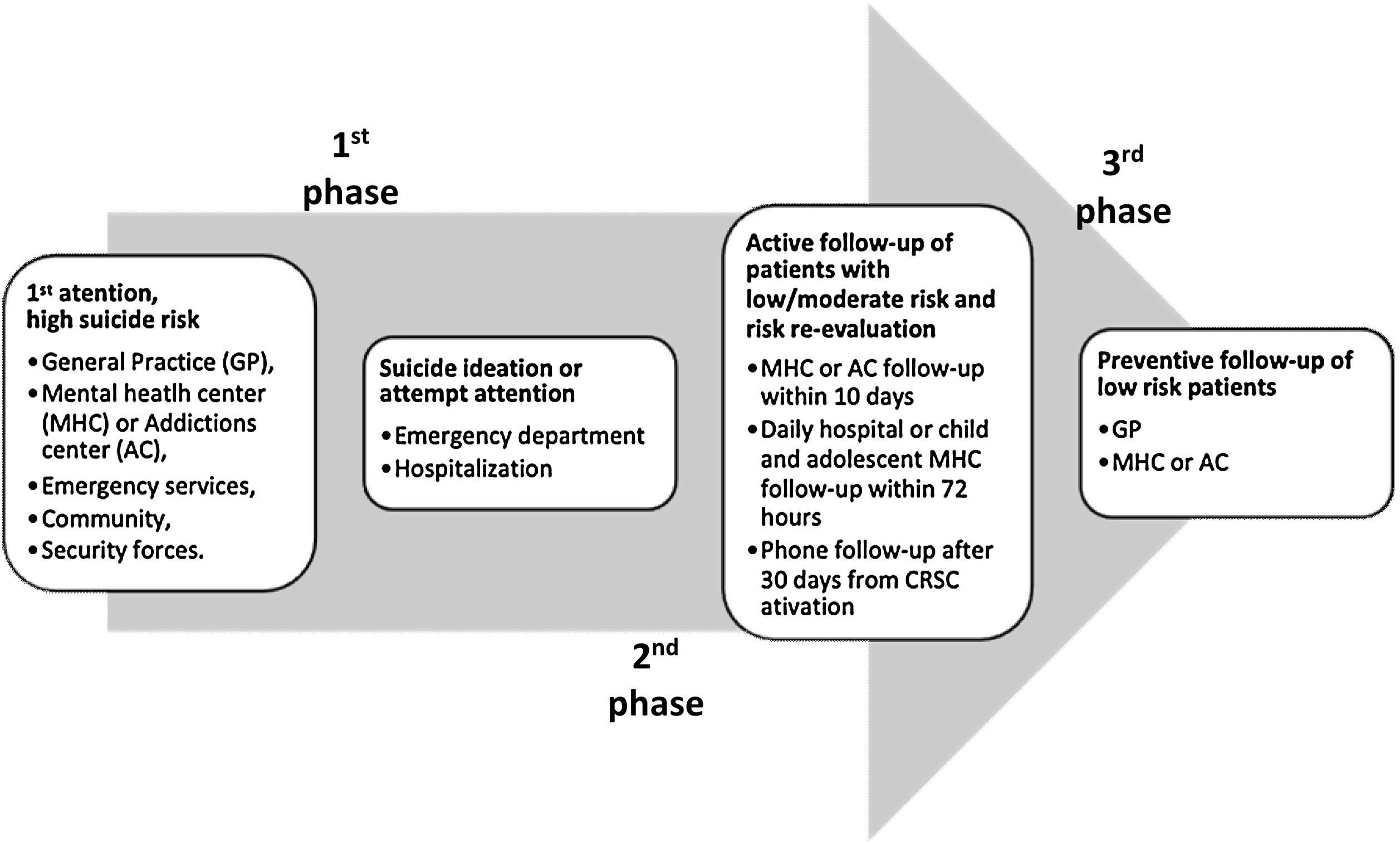

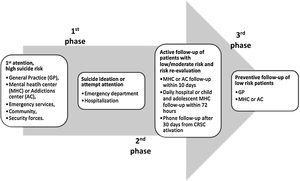

Materials and methodsThe CSRC program is divided in 3 phases: (1) alert and activation, (2) proactive telephone and face-to-face follow-up and (3) comprehensive preventive health monitoring. This is the analysis of the sample of patients attempting or intending suicide who were seen at a tertiary hospital in Barcelona, and their 1-year follow-up outcome.

ResultsThree hundred and sixty-five patients were included. In 15% of the cases, there was no previous psychiatric history but in the majority of cases, a previous psychiatric diagnosis was present. The most common type of suicide attempt was by drug overdose (84%). Up to 66.6% of the patients attended the scheduled follow-up visit in the CSRC program. A significant reduction in the proportion of patients visiting the emergency room for any reason (but not specifically for a suicide attempt) and being hospitalized in the first semester in comparison with the second six months after the CSRC activation (30.1% versus 19.9%, p=0.006; 14.1% versus 5.8%, p=0.002) was observed.

ConclusionsThe clinical risk factors and the findings of the CSRC helped in the characterization of suicide attempters. The CSRC may contribute to reduce hospitalizations and the use of mental health care resources, at least in the short-term.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one person every 40s dies by suicide, and close to 800,000 people every year.1 For each adult who died by suicide there may have been more than 20 others attempting suicide,1 with an attempted suicide rate in Spain estimated to be 99.1 per 100,000 inhabitants.2 A suicide attempt is defined as a nonfatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behavior with an intent to die as a result of this behavior even if the behavior does not result in injury. In addition, suicidal ideation, which is common in suicide attempts, is defined as thinking about, considering, or planning suicide.3

Having a psychiatric diagnosis and more specifically a mood disorder is a strong predictor for a suicide attempt.4 Suicide attempters and multiple attempters have been found to have higher levels of depression, hopelessness, aggression, hostility, and impulsivity and were more likely to have borderline personality disorder and family history of major depression or alcohol use disorder compared with non-attempters.5 Childhood trauma, especially physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and physical neglect, have also been reported as an important risk factor for suicide attempts.6 Severe mental disorders, family history of suicide, early onset, extent of depressive symptoms, increasing severity of episodes, comorbidity with Axis I disorders, and abuse of alcohol or drugs were described as specific risk factors for a suicide attempt.7 Nonetheless, by far the strongest risk factor for suicide and a suicide attempt is a previously attempted suicide.4,7 Furthermore, after being discharged from the emergency room due to a suicide attempt, one out of ten patients reattempted within five days,8 with an elevated risk of reattempt for an extended period of time.9

The possibility to intervene in suicide attempts or suicidal ideation through primary and secondary suicide prevention programs, represent one of the most important challenges in preventive medicine. A recent systematic review explored different suicide prevention interventions, demonstrating the benefits of restricting access to lethal means or school-based awareness programs.10 Screening in primary care, in general public education and media guidelines have shown insufficient evidence, mainly due to the paucity of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in the evaluation of prevention interventions.10 Moreover, the lack of continuity of care after a suicide attempt represents one of the major limitations for an effective suicide prevention program.11 Indeed, secondary prevention programs with an active follow-up have been seen to reduce the risk of repeated suicide attempts in the 6 months after discharge from the emergency room for suicidal behavior.12

The number of countries with national suicide prevention strategies has increased since the publication of the WHO's first global report on suicide in 2014.13,14 Despite this, the total number of countries with specific and national strategies is still small. Consequently, governments need to commit in the attempt to establish effective preventive plans.15

Notwithstanding the importance and relevance of the subject, in Spain there are still many limitations in the area.16 Even though the scientific community is sensitive to the importance of the topic, as highlighted by the growing number of publications and the recommendations of the national societies, there are still many gaps at the clinical and practical level.17

First, systematic and standardized assessment and registration of the suicidal risk is poorly made,18 and does not include, in many occasions, aspects of clinical prognostic importance such as the presence of previous suicide attempts.16 Furthermore, the use of psychometric scales to aid in the risk assessment of suicidal behavior has not yet been routinely incorporated into the daily clinical practice.19 Another important point is the lack of specific preventive programs in at-risk populations, such as those suffering from severe mental illness or those that already attempted suicide.16 Finally, Spain has not yet developed a national consensus-based health policy. However, there are different regional strategies for each region and specific programs applied in few cities.20

In 2014 Catalonia started a multilevel suicide secondary prevention program, the Catalonia Suicide Risk Code (CSRC),2 in order to improve the suicide preventive strategy. The goals of the CSRC,21 are; (1) creating a specific protocol to be applied by all the health agents involved, especially in emergency settings; (2) ensuring a homogeneous procedure for acting in hospital emergency settings; (3) implementing a post-discharge emergency and/or hospitalization follow-up procedure; (4) ensuring a follow-up by mental health and primary care providers during the 12 months after a suicide attempt/suicidal ideation. The final objective is to reduce mortality by suicide and to reduce the number of new attempts. A recent observational study describes clinical characteristics and adherence of patients included in this program. This study mentions some limitations in the adherence to this program, and emphasizes the importance of future studies exploring the impact of the CSRC in reducing not only suicide reattempts, but also hospitalizations and use of the emergency resources.2

The aim of the present study is to describe the CSRC preventive strategy experience in a tertiary hospital in Barcelona, presenting the data obtained in the baseline and follow-up evaluations, particularly focusing on the impact in health care utilization. Furthermore, the importance of the clinical assessment and the identification of variables that could confer higher risk of suicide attempt were explored.

MethodsStudy designThis is a prospective cohort study including patients, living in the catchment area of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain), with an activated CSRC from July 14th 2014 until November 1st 2017. The Hospital Clinic acts as a community general hospital, which covers a population of 540,000 inhabitants from the south of the city. It also operates as a tertiary and university (University of Barcelona) health care facility for highly complex psychiatric cases, and it is one of the most active research members of the Center of Biomedical Research Network in Mental Health.22

In the present study, we included all the patients aged ≥18 years, with activated CSRC because of suicidal ideation or a suicidal attempt. We collected their clinical data at baseline and during a 12 months follow up. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (approval code number HCB/2017/0211) and all the patients gave their oral consent to be included in the CSRC.

ProceduresThe Catalonia Suicide Risk Code (CSRC) was developed in 2014 in the Catalonia region (ES), in order to prevent suicide attempts. More than 90 primary care services and hospitals in Catalonia have been included. The program has been described in detail elsewhere.2

Briefly, the CSRC includes three phases (Fig. 1): (1) Alert and activation phase: the emergency room staff evaluates the risk of the suicidal behavior and ask the patient to be included in the CSRC. The psychiatrist completes the MINI suicidal module, from MINI Interview,23 a risk factor checklist, and assesses the clinical risk at entrance and discharge. The psychiatrists at the Emergency Room received specific training in completing the CSRC website and its modules before the CSRC was started. Furthermore, audits were conducted and recommendations were provided for the implementation of the CSRC after its application was established. (2) Follow-up: two different pathways are activated. One consists of a follow-up phone call from a regional emergency system after 30 days of discharge, in order to detect alarm signs or the worsening of the clinical symptoms. At the same time, the patient is given an appointment in the outpatient clinic before their 10th day after discharge. In this first follow-up visit the psychiatrist, on the basis of the clinical condition, decides if the patient needs to be followed-up in the Mental Health Service during a one-year period or can be discharged because the risk no longer exists. (3) The general practitioner follows-up the patient in order to improve the prevention of the risk of suicide.

An ad-hoc dataset of the CSRC has been created and each doctor visiting patients in the Emergency Room can access the electronic website with his/her personal data.

Data extractionThree research members SGC, NV and ES were specifically trained to obtain data for the purpose of the study, through specific designed patients’ charts on baseline and follow-up study points (6 and 12 months). Data extraction was anonymously made from the specific CSRC website (https://salut.gencat.cat/pls/gsa/gsapk030.portal).

Baseline evaluationThe following socio-demographic and clinical information were collected for each patient, when available: sex; birth date; age; Mental Health outpatient facility of the patient; DSM-5 diagnoses (including substance-related disorders); substance abuse during the suicide attempt; type of suicide attempt (i.e. drug overdose, precipitation, hanging, poisoning, drowning, severe cutting) including suicidal ideation without the attempt; clinical risk assessment.

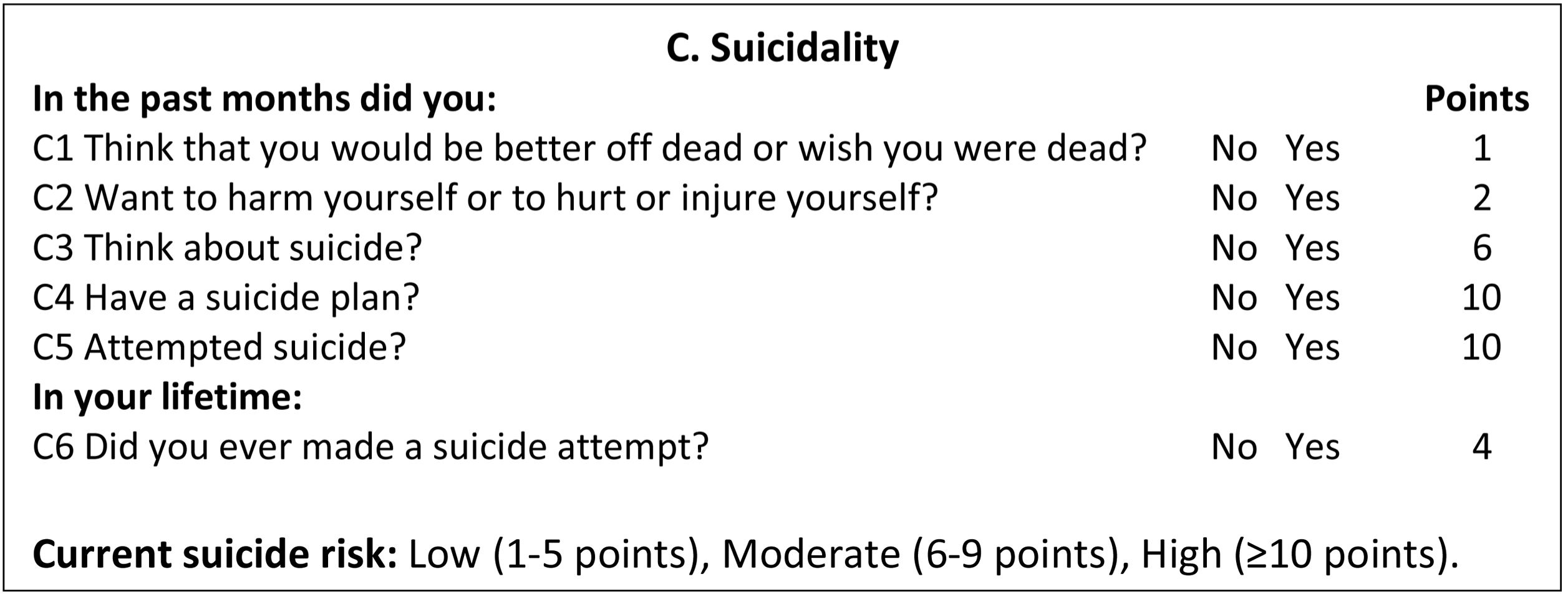

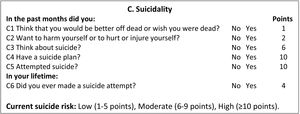

The MINI suicidal module was administrated at entry and discharge from the Emergency Room. The MINI suicidal module (Fig. 2) is a validated submodule of the MINI, consisting of a short structured diagnostic interview with nine items.23 In the CSRC, a shorter version was used, with six items that were scored yes or no (Fig. 2). Whilst items 1–5 record whether an event has occurred during the last month, item 6 records the lifetime occurrence of the event (Fig. 2). Each item score is weighted according to its estimated contribution to risk level. The aggregated score range of the short version is 0–33 points.24

Assessment of follow-up variablesThe follow-up information was collected: the number of days until the CRSC proposed follow-up consultation with a psychiatrist at the outpatient clinics; the number of completed suicides; patients attending the follow-up visit and the reasons for not attending were also collected. Specific follow-up outcomes considered and obtained in the present study were (1) the number of Emergency Room evaluations due to any reason; (2) the number of Emergency Room evaluations due to a suicide attempt/suicidal ideation; (3) the number of Psychiatric Hospitalizations. These follow-up measures were recorded at 6 months and one year, when available.

Statistical analysesDescriptive statistical analysis for demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample was performed. Normality of distribution for continuous variables was evaluated with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, visually and with the skewness and kurtosis values.

McNemar's test, the chi-square test for repeated measures in the same sample, was conducted in order to assess the differences in the proportion of patients visiting the Emergency room for any reason or for a suicide attempt or being hospitalized in the first semester versus the second semester after the activation of the CSRC.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Statistical Package for Social Science-SPSS, 23.0 version for Windows Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsBaseline socio-demographic and clinical featuresA sample of 365 patients was enrolled. Two-hundred eighteen (59.7%) were female. The mean age was 44.9 (±15.7), ranging from 18 to 92 years.

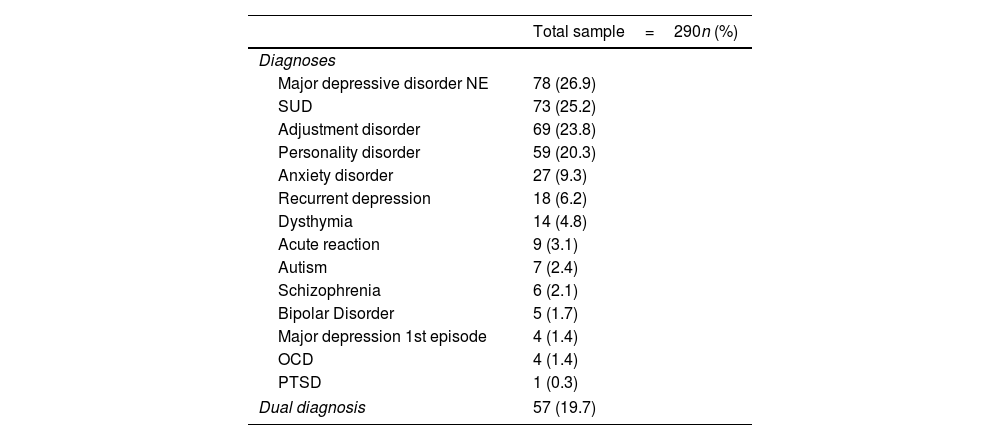

Fifty patients (14.7%) had no previous psychiatric diagnosis whilst 290 patients (85.3%) had at least one psychiatric diagnosis.

Among the 290 patients with a previous diagnosis, 64 patients (22%) had more than one diagnosis. The different psychiatric diagnoses are reported in Table 1.

Baseline psychiatric diagnoses.

| Total sample=290n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Diagnoses | |

| Major depressive disorder NE | 78 (26.9) |

| SUD | 73 (25.2) |

| Adjustment disorder | 69 (23.8) |

| Personality disorder | 59 (20.3) |

| Anxiety disorder | 27 (9.3) |

| Recurrent depression | 18 (6.2) |

| Dysthymia | 14 (4.8) |

| Acute reaction | 9 (3.1) |

| Autism | 7 (2.4) |

| Schizophrenia | 6 (2.1) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 5 (1.7) |

| Major depression 1st episode | 4 (1.4) |

| OCD | 4 (1.4) |

| PTSD | 1 (0.3) |

| Dual diagnosis | 57 (19.7) |

Notes: NE, Non specified; SUD, Substance use disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

From the whole sample, in 270 patients (74%) the prevention program was activated in the context of a suicide attempt. To a lesser extent, the CSRC was activated in 95 patients (26%) because of suicidal ideation, without a suicide attempt.

Among the 270 suicide attempters, 19 (7%) mentioned previous planning of the suicide attempt.

In the sample (data available for 226 patients), 15 (6.6%) patients were hospitalized at discharge from the Emergency Room.

Type of suicide attemptAmongst the different types of suicide attempts, the most common were intoxication by any kind of noxious agent, occurring in 84.4% of the patients, followed by cutting 10% and other less used methods such as jumping from a high place 1.1%, hanging 0.8%, drowning 0.4%. In 3.3% of cases, the method was not specified.

Out of 351 patients (14 patients with missing information), 50 patients (13.7%) presented drug intoxication during the suicide attempt. In particular, alcohol intoxication was the most frequent (76%), followed by cocaine (12%), morphics (8%), cannabis and amphetamines (2% each).

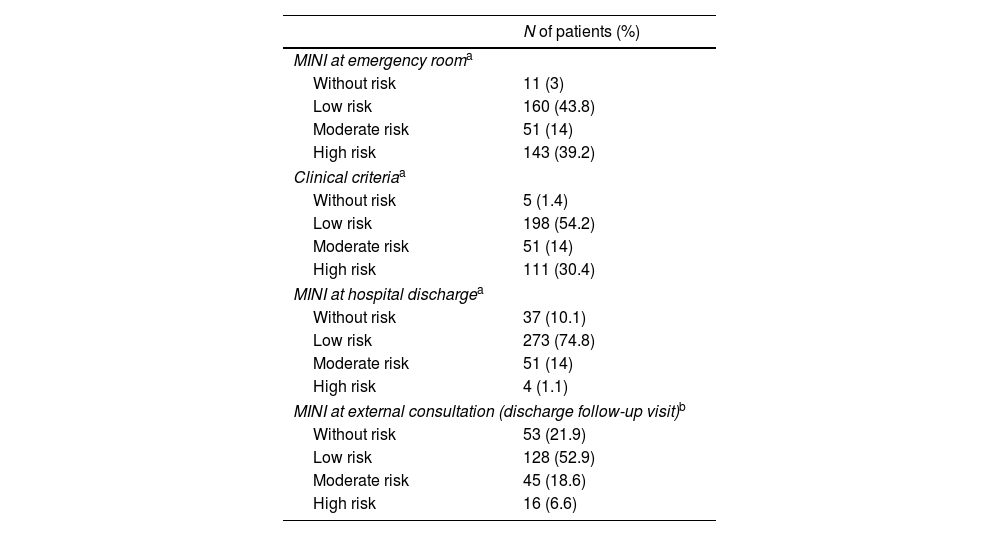

Suicidal risk scoresThe scores of the MINI suicidal module were evaluated and recorded in different phases, namely at the Emergency Room, hospital discharge and after the first external consultation at the psychiatric outpatient clinic. Also, scores based on clinical criteria at the first Emergency Room visit were collected. The results are detailed in Table 2.

Suicidal risk scores.

| N of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| MINI at emergency rooma | |

| Without risk | 11 (3) |

| Low risk | 160 (43.8) |

| Moderate risk | 51 (14) |

| High risk | 143 (39.2) |

| Clinical criteriaa | |

| Without risk | 5 (1.4) |

| Low risk | 198 (54.2) |

| Moderate risk | 51 (14) |

| High risk | 111 (30.4) |

| MINI at hospital dischargea | |

| Without risk | 37 (10.1) |

| Low risk | 273 (74.8) |

| Moderate risk | 51 (14) |

| High risk | 4 (1.1) |

| MINI at external consultation (discharge follow-up visit)b | |

| Without risk | 53 (21.9) |

| Low risk | 128 (52.9) |

| Moderate risk | 45 (18.6) |

| High risk | 16 (6.6) |

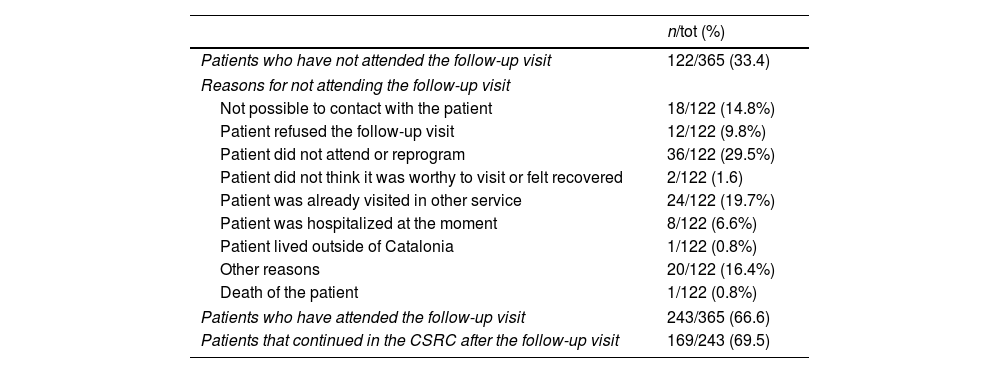

Among the 365 patients with activated CSRC, 66.6% (n=243) attended the first follow-up visit. The 33.4% (n=122) of the total did not attend the follow-up visit (reasons for not attending are described in Table 3). The mean waiting time between the activation of the CSRC at the discharge from the Emergency Room and the follow-up visit at the Mental Health Service was 5.9 days (±8.4).

Clinical characteristics of follow-up.

| n/tot (%) | |

|---|---|

| Patients who have not attended the follow-up visit | 122/365 (33.4) |

| Reasons for not attending the follow-up visit | |

| Not possible to contact with the patient | 18/122 (14.8%) |

| Patient refused the follow-up visit | 12/122 (9.8%) |

| Patient did not attend or reprogram | 36/122 (29.5%) |

| Patient did not think it was worthy to visit or felt recovered | 2/122 (1.6) |

| Patient was already visited in other service | 24/122 (19.7%) |

| Patient was hospitalized at the moment | 8/122 (6.6%) |

| Patient lived outside of Catalonia | 1/122 (0.8%) |

| Other reasons | 20/122 (16.4%) |

| Death of the patient | 1/122 (0.8%) |

| Patients who have attended the follow-up visit | 243/365 (66.6) |

| Patients that continued in the CSRC after the follow-up visit | 169/243 (69.5) |

| Mean (±SD) | Min–Max | |

|---|---|---|

| Days between the activation of the CSRC and the follow-up visit | 5.9 (±8.4) | 0–92 |

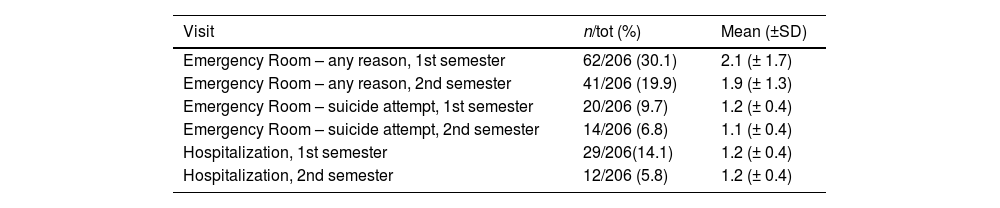

The proportion of patients and the number of visits at follow-up in the two different time points (6 and 12 months) after the activation of the CSRC are listed in Table 4.

Mental healthcare utilization at 6 and 12 months after the CSRC activation.

| Visit | n/tot (%) | Mean (±SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency Room – any reason, 1st semester | 62/206 (30.1) | 2.1 (± 1.7) |

| Emergency Room – any reason, 2nd semester | 41/206 (19.9) | 1.9 (± 1.3) |

| Emergency Room – suicide attempt, 1st semester | 20/206 (9.7) | 1.2 (± 0.4) |

| Emergency Room – suicide attempt, 2nd semester | 14/206 (6.8) | 1.1 (± 0.4) |

| Hospitalization, 1st semester | 29/206(14.1) | 1.2 (± 0.4) |

| Hospitalization, 2nd semester | 12/206 (5.8) | 1.2 (± 0.4) |

The comparison between those patients visiting the Emergency room for any reason or for a suicide attempt or being hospitalized in the first semester versus the second semester has been conducted on 206 patients out of 365, whose data on these variables was available.

A significant reduction has been observed in the proportion of patients visiting the Emergency room, for any reason and being hospitalized in the first semester in comparison with the second semester after the CSRC activation (30.1% versus 19.9%, p=0.006; 14.1% versus 5.8%, p=0.002). No significant difference was observed in the proportion of patients visiting the Emergency room, for a suicidal attempt/ideation in the first semester in comparison with the second semester, although the rate was numerically smaller (9.7% versus 6.8%, p=0.307).

DiscussionThe present study describes a suicide preventive clinical strategy, the CSRC. Particularly, data obtained in the baseline and follow-up evaluations are presented.

Only a small proportion of the patients, around 15% of the cases, had no previous psychiatric history, whilst the majority of them presented a previous psychiatric diagnosis. The most frequent cause of attempted suicide was by drug overdose.

Six out of ten patients attended the follow-up visit in the CSRC program. In terms of health care utilization, a significant reduction from the first semester after the CSRC activation to the second one was observed in the proportion of patients visiting the Emergency room for any reason and being hospitalized in a psychiatric ward.

Epidemiology and risk factorsSimilarly, to previous studies,25–28 the prevalence of female patients attempting suicide was higher than male patients.

Most patients in our study had a previous psychiatric diagnosis. This result has also been previously reported in studies supporting the frequent association between psychiatric past history and suicidal behavior.29–33

The most frequent diagnoses in our sample were major depressive disorder not otherwise specified or adjustment disorder, as well as substance use disorder and personality disorder. Similarly, in previous literature anxiety, depressive, and alcohol use disorders were the most prevalent disorders among suicide attempters in general.33

Moreover, symptoms such as low mood (measured as a continuous variable rather than a discrete mental disorder), hopelessness, and impulsivity, which are common in those specific diagnoses, are also considered to be particularly important predictors of suicidal thoughts and attempts.3 In the same way, previous studies remark the importance of cluster B personality disorder and borderline symptoms as risk factors for suicide attempts, in accordance with our results.34,35

In addition, more than one out of ten patients attempted suicide with drug overdose, and in almost two out of ten patients, a dual diagnosis was present. This is consistent with previous evidence showing that suicidal behavior is a significant problem for people with co-occurring substance use disorders. The combination of different precipitating risk factors such as recent heavy substance use and intoxication as well as personality traits and mental illnesses has been seen to intensify the risk for suicidal behavior in dual diagnosis patients.36

A noteworthy finding was that, the prevalence of severe mental illness diagnosis such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder was quite low in our sample and definitely lower than expected according to previous studies, where severe mental disorders are considered an important risk factor for suicide behavior.29,37 A possible explanation for these differences could be that patients suffering from bipolar disorder or schizophrenia generally commit more severe and lethal suicide attempts so they do not generally attend the psychiatric emergency room because they require medical assistance.38 It is important to highlight that, the present study relies on a registry of data collected at the psychiatric emergency room, that does not include all the data on suicide of our territory. Moreover, the Hospital Clinic has two very prominent units, one for Bipolar Disorder and another one for Schizophrenia, that provide not only tertiary care but also community care for patients in the catchment area.39,40 Hence, it is likely that any suicidal ideation or event may have been captured and addressed by those units, out of the scope of the Emergency room.

Type of suicide attemptIn our study, the most common type of suicide attempt was by drug overdose, similarly to previous literature. Drug intoxications, are by far the most frequently used method, mainly among females.25 Interestingly, research on suicide methods could lead to the development of gender-specific intervention strategies.41

Suicidal risk scoresRegarding suicidal risk scores, more than a half of the patients were initially evaluated according to the MINI suicidal module from moderate to high risk, at the Emergency Room, which was similar to the clinical criteria evaluation. At discharge the risk was lower, with only one out of six patients with a moderate to high risk evaluation. This could be due to the fact that the CSRC should be activated when the patient comes to the Emergency Room and, after a clinical observation period, the suicidal risk is re-evaluated and a clinical decision should be made. If the patient continues to be suicidal and keeps scoring high in the MINI suicidal module, psychiatric hospitalization was eligible. If the suicidal risk is low or absent, the patient is discharged by the Emergency Room and a follow-up visit is planned at the community mental health service, within the CSRC. This is consistent with the low rates of hospitalizations in the present sample. An important aspect is that one out of four patients still presents high or moderate risk at the evaluation with the community mental health team, which underlines the main important aspect of this program which is that the patient feeling suicidal has fast access to the psychiatric follow-up.

As a consequence, suicidal assessment by means of specific assessing tools allows the quantifying of the severity of patients’ symptoms, and could be then implemented, as a complementary tool, in routine use in emergency departments in order to tailor case management.19

Nonetheless, a high percentage of patients did not attend the follow-up visit, despite the fact that the time period from the discharge from the emergency room to the follow-up visit in the outpatient clinic was less than one week.

Healthcare contact at 6 and 12 monthsA significant reduction of consultation in the Emergency Room and of the hospitalization rate was found in the second semester after the activation of the CSRC in comparison with the first one. However, the number of Emergency Room visits due to a suicidal attempt was not significantly reduced. It can be hypothesized that if the patient is involved in a specific follow-up program, he or she will less possibly need to be visited at the Emergency Room because he/she is already involved in a longitudinal care system, with important implications in terms of mental health costs.12 As underlined by Inagaki and colleagues in their recent meta-analysis on interventions to prevent repeated suicide attempts, active contact and follow-up type interventions could reinforce the therapeutic connection between patients and care providers, reducing the risk of a repeated suicide attempt within 6 months.12 Indeed, one of the major issues in the prevention of suicide reattempts is the lack of continuity of care following a suicide attempt.11 The time window for preventing a suicide reattempt should be considered. In a Danish case-control study performed between 1981 and 1997, the risk of reattempt of suicide was higher during the first week following psychiatric hospital discharge.42 Interestingly, the risk declined in the following weeks and months.42 As a consequence, policy makers should prioritize the promotion of continuity of mental health care for those patients at high risk of suicide during the period immediately following hospital discharge.11 Similarly to our results, a British observational study that provided a 7-day follow-up intervention after psychiatric hospital discharge was associated with a significant decline in suicide reattempts during the 3-month period following hospital discharge.43

One of the important limitations of the CSRC is the quite high dropout rate, which has also been outlined in a recent article explaining the development of the protocol in Catalonia.2 Furthermore, there might be an underutilization of the protocol by the mental health providers. As a consequence, further analyses on the process of implementation of the CSRC should be provided. Another important limitation to consider is the lack of comparison group since this study was done as an observational study. Finally, the CSRC is mostly focused on non-fatal suicidal behavior, and therefore its impact on suicide rates is still unknown. An epidemiological analysis of the comparison between the outcomes of the CSRC intervention and the regional rates of death by suicide should be further explored.

Despite these limitations, the CSRC protocol is an example of the attempt to improve surveillance and monitoring of suicidal patients, that is one of the most important challenges according to the World Health Organization.

ConclusionsThe most important finding of the present study is that the application of the CSRC protocol was found to reduce hospitalizations and the mental health care utilization in the first year after the discharge from the Psychiatric Emergency Room, which represents a high risk time window for suicide reattempt. This, despite other non-significant outcomes, is the main finding of the study, which represents a first approach to test the impact of a regional health care policy intended to reduce suicidal behavior.

Finally, further knowledge on suicide attempts and their risk factors is required for the design of future effective suicide prevention strategies. As it has been recently considered, the current body of evidence on preventive efforts on suicide prevention is substantial, and policy-makers should start using this knowledge to take charge and reduce suicide numbers.44 As a consequence, the implementation of suicide prevention protocols, such as the one described in this article, should be guaranteed and further investigated and improved in order to overcome current limitations on the implementation of this health policies.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors. This research was indirectly funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la Investigación with the grants PI18/00805 to EV, PI19/00954 to MV, MG and MC, PI17/01205 to DP, PI19/00236 to VP. NV research is supported by a BITRECS Project, which has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement N° 754550 and from “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434), under the agreement LCF/PR/GN18/50310006.

Conflict of interestProf. Vieta has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, Abbott, Allergan, Angelini, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda, the Brain and Behaviour Foundation, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM), the EU Horizon 2020, and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

Dr. Pacchiarotti has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from ADAMED, Janssen-Cilag and Lundbeck and reports no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

Dr. Gomes Da Costa has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from Janssen-Cilag, Italfarmaco, Angelini and Lundbeck and reports no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

Dr. Garriga has received grants and served as consultant or advisor for Ferrer, Lundbeck, Janssen, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Instituto de Salud Carlos III through a ‘Rıo Hortega’ contract (CM17/00102), FEDER, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2017SGR1365), and the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya, all of them unrelated to the current work.

Dr. Cavero has received CME-related honoraria, and also served as consultant or advisor for Lundbeck, Pfizer, Exeltis and Servier, without any relation to the current work.

Dr. Vázquez has received CME-related honoraria, and also served as consultant or advisor for Lundbeck.

Dr. Palao has received grants and also served as consultant or advisor for Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck and Servier.

Dr. Perez has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants from AB-Biotics, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, CIBERSAM, FIS- ISCiii, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier, Pfizer and Esteve.

Dr. Blanch has received grants and served as consultant or advisor for Gilead, Ferrer International. Janssen, and MSD, all of them unrelated to the current work.

Dr. Sole, Dr. Giménez, Dr. Williams and Dr. Verdolini have no conflict to declare.

The Catalonia Suicide Risk Code is an initiative of the Mental Health and Addictions Plan of the Department of Health of the Catalan Government. The authors thank the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for their support integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I and co-financed by the Instituto Salud Carlos III-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the Instituto de Salud Carlos III; the CIBERSAM (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental); the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2017_SGR_1365) and the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya. EV receives a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI18/00805), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la Investigación. MV, MG and MC receive a grant from ISCIII/FEDER PI19/00954. DP receives also funding by ISCIII/FEDER PI17/01205. VP also receives funding by ISCIII/FEDER PI19/00236 We thank all the study participants. NV research is supported by a BITRECS Project, which has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement N° 754550 and from “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434), under the agreement LCF/PR/GN18/50310006. We thank all the study participants.