Childhood trauma has been associated with an increased risk of psychosis, a greater severity of psychopathological symptoms, and a worse functional prognosis in patients with psychotic disorders. The current study aims to explore the relationship between childhood trauma, psychopathology and social adaptation in a sample of young people with first episode psychosis (FEP) or at-risk mental states (ARMS).

Material and methodsThe sample included 114 young people (18–35 years old, 81 FEP and 33 ARMS) who were attending an Early Intervention Service for Psychosis. Positive, negative and depressive symptoms were assessed with the PANSS and the Calgary Depression Scale; history of childhood trauma was assessed with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; social adaptation was assessed with the Social Adaptation Self-evaluation Scale (SASS). Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to explore the relationship between childhood trauma, psychopathology and SASS dimensions in the global sample (including FEP and ARMS). An exploratory SEM analysis was repeated in the subsample of FEP patients.

ResultsARMS individuals reported more emotional neglect and worse social adaptation compared to FEP. SEM analysis showed that childhood trauma is associated with a worse social adaptation, in a direct way with domains involving interpersonal relationships, and mediated by depressive symptoms with those domains involving leisure, work and socio-cultural interests.

ConclusionsChildhood trauma has a negative effect on social adaptation in young people with early psychosis. Depressive symptoms play a mediation role in this association, especially in domains of leisure and work.

El maltrato infantil se ha asociado a un mayor riesgo de psicosis, a una mayor severidad en síntomas psicopatológicos y a un peor pronóstico funcional en pacientes con un trastorno psicótico. El presente estudio pretende evaluar la relación entre el maltrato infantil, psicopatología y la adaptación social en una muestra de primeros episodios psicóticos (PEP) y de estados mentales de alto riesgo (EMAR).

Material y métodosLa muestra incluyó 114 jóvenes (18–35 años, 81 PEP y 33 EMAR) atendidos en un Servicio de Intervención Precoz en Psicosis. Se evaluaron síntomas positivos, negativos y depresivos con las escalas PANSS y Calgary de Depresión; los antecedentes de maltrato infantil con el Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; la adaptación social con la Escala Autoaplicada de Adaptación Social (SASS). Se utilizó el modelo de ecuaciones estructurales (SEM) para explorar relaciones entre psicopatología, maltrato infantil y dimensiones de la SASS en toda la muestra (incluyendo PEPs y EMAR). Se repitió un análisis SEM exploratorio en la submuestra de PEPs.

ResultadosLos EMAR presentaron más negligencia emocional y peor adaptación social, comparados con los PEP. El SEM muestra que el maltrato se asocia con una peor adaptación social en todos los dominios, de forma directa en dominios que implican relaciones interpersonales, y por una vía mediada por síntomas depresivos en los dominios que implican ocio y trabajo e intereses socio-culturales.

ConclusionesEl maltrato infantil tiene un efecto negativo sobre la adaptación social en jóvenes en fases tempranas de las psicosis. Los síntomas depresivos son mediadores de una peor adaptación en aspectos funcionales relacionados con el ocio y el trabajo.

Childhood trauma is a risk factor for the development of psychosis,1 and has also been associated with the severity of positive psychotic symptomatology.2 Recent meta-analyses suggest that sexual abuse is associated with greater severity of hallucination and delusion symptoms, whilst neglect is associated with a higher severity of negative symptoms.3 With regard to therapeutic response, patients with a psychotic disorder with a background of childhood trauma present with a worse functional prognosis, with lower rates of response.4 Studies in samples of patients with early stage psychotic disorders suggest that the negative impact of childhood trauma in a worse functional prognosis is measured by symptoms of depression.5 Several studies suggest that a background of childhood trauma would be associated with worse premorbid adjustment, particularly at academic and social levels.6 Social defeat suggests that the exposure to stressful situations which lead to exclusion from the majority group, including migration or a background of childhood trauma, play a role in the pathogenesis of psychotic disorders.7 Along these lines, the relationship between childhood trauma and the severity of psychotic symptoms in patients with psychotic disorders appears to be measured by solitude, which previous authors have related to social defeat and which would lead to psychological malaise for patients with the presence of symptoms of depression and anxiety.8 Other studies9 conducted with patients at high risk of presenting with a psychosis (at risk mental states, ARMS) suggest that perceived stress is a mediator of the relationship between a worse social adaptation, assessed with the social adaptation self-evaluation scale (SASS), and a worse quality of life.

The aim of our study was to explore the relationship between a childhood trauma and social adaptation in young patients who were being monitored by a team of early intervention service for psychosis and its possible relationship with psychopathological symptoms (depressive, positive or negative). In our study a structural equation modelling [SEM])10 was used to explore the relationships between childhood trauma, psychopathology and the different dimensions of social adaptation of the SASS scale, which in the validation article by Bobes et al.11 were defined as four: 1) extra-familial relationships, 2) leisure and work, 3) sociocultural interests, 4) family relationships and behavioural strategies. Our hypothesis was that a background of childhood trauma would lead to poorer adaptation both through a pathway mediated by depressive symptoms and directly, particularly in those dimensions involving interpersonal relationships.

Material and methodsSampleThe study included 114 patients who were attending and being monitored by the team of an early intervention service for an FEP (N = 81) or an ARMS (N = 33). Diagnosis of FEP was made by means of a SCAN interview12 administered by a psychiatrist and the OPCRIT version 4.0. software to generate a psychotic disorder diagnosis with DSM-IV criteria. The diagnosis of ARMS was obtained with a Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS)13 interview with operative criteria that are used in the Early Psychotic Disorder Care Programmes (PAE-TPI for its initials in Spanish) in Catalonia, which are: 1) tempered psychotic symptoms, 2) intermittent psychotic symptoms, 3) vulnerability group, defined as the patient with personal backgrounds of schizotypal personality disorder or a family history of psychosis. To classify the ARMS in these 3 subgroups scores of the positive symptoms subscales of the CAARMS were considered (P1: unusual thought content, P2: non bizarre ideas; P3: percepual abnormalities, P4: disorganised speech) and the change on the Activities Assessment Scale (ASS) on functionality. The P1 to P4 subscales of the CAARMS were rated from 0 to 6 on both severity and frequency. The diagnostic criteria of ARMS, bearing in mind the cut-off scores of the CAARMS were specified in the Appendic B Appendix, table S1 of the supplementary material. The symptoms had to be present 12 months previously, having lasted under 5 years, and there had to be impairment of functionality (30% reduction on the Activities Assessment Scale (ASS) or an ASS score < 50 points).

All the participants in the study werer previously informed of its content and gave their signed consent. This study was assessed and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Sant Joan de Reus and framed within a FIS project (PI10/01607; IP: Javier Labad) financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Clinical assessmentThe Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)14 was used to assess positive, negative psychotic symptoms and psychopathology in general. The self-applied Calgary scale for depression in schizophrenia,15 was administered to patients to also assess depressive symptoms. Histories of childhood trauma were assessed with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, CTQ).16,17 The CTQ is a self-applied tool consisting of 28 items for adults which assesses childhood trauma retrospectively. The CTQ records five types of childhood trauma: sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect. Each scale is represented by five items which are given a score on a Likert type 5-point scale ranging from never to very often. Three additional items make up the minimisation scale.

Social adaptation was assessed with the SASS self-administered scale. As explained in the article validated into Spanish,11 this is a 21 item scale, with four levels or response (0–3), which assesses motivation and social conduct. The items explore the functioning of the individual in different areas: work, family, leisure, social relationships and motivation/interest. There are two mutually excluding items and each subject only responds to one of them depending on whether or not they have a salaried job or profession. As a result, for computing purposes it is considered to have 20 items, with a total score range of between 0 and 60. Higher scores denote greater social functioning.

Statistical analysisFor the univariate statistics the SPSS version 21.0 (IBM, U.S.A.) software was used. The categorical variables were compared between groups with chi-square tests. The continuous variables were compared with the Student’s t-test. A P < .05 value was considered significant.

The SEM analysis was performed with R (https://www.r-project.org/about.html) using the lavaan package. We decided to use a SEM analysis because this statistical technique has the advantage of allowing simultaneous analysis of all variables of the model instead of testing them separately.10 The SEM models also allow one to work on certain psychometric scales in a dimensional manner by grouping items with confirmatory factorial analysis methodology. The SEM models favour the design of relational models based on hypothesis and assessment of model validity considering a certain grouping of variables. One major aspect is the generation of latent variables which are variables that have not been directly measured, but which group together a set of variables which have been measured. A latent variable may therefore be considered as a “hypothetical” factor (defined a priori for testing in the model) which constitutes the construct that represents multiple observed variables. Another advantage of the SEM analysis is that multiple indicators of the same construct may be managed naturally without there being any problems of co-lineality that could appear in multiple lineal regressions.

The latent variables were considered to be childhood trauma and psychopathological symptoms (positive, negative, and depressive). The childhood trauma variable was composed of scores in the 5 dimensions of the CTQ: sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect. For psychopathological symptoms the grouping of the PANSS symptoms was considered according to a consensus as the factorisation of the PANSS symptoms,18 adding the total score of the Calgary Depression scale for the depressive symptoms factor. As a result the positive factor included PANSS positive items of delusions, hallucinations, grandiosity and general unusual thought content. The negative factor included negative PANSS items of blunted effect, emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, passive/apathetic social withdrawal, lack of spontaneity and general motor retardation; the depressive factor included the PANSS general anxiety, guilt feelings and depression, in addition to the total score of the Calgary Depression for Schizophrenia scale. The variances of all latent variables were fixed at 1 to use standardised scores in the SEM model. As dependent variables the 4 SASS factors suggested by the article of validation into Spanish were considered: 1) extra-familial relationships (items 8, 12, 17); 2) leisure and work (items 1/2, 3, 4, 5, 19, 21); 3) sociocultural interests (items 14, 15, 16); family relationships and behavioural strategies (items 7, 13, 18, 20). Three model adjustment indexes were considered: Chi-square (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Ideally, in a model with highly accurately goodness of fit to the data, the χ2 test would not be significant (P > .05).19 This test assesses the null hypothesis that the predictor model and observed data are equal. If the test is significant there are differences between the predictor model and the observed data. Therefore, a non significant result indicates a good match. CFI values above 0.9 indicate a good fit of the model and values above 0.8 a moderate fit.20 The SRMR index represents the standardised difference between the observed and predicted correlation. A SRMS value under 0.08 is generally considered a good fit.20 Given that these indexes, and in particular the χ2, are affected by sample size, several authors have suggested adjusting the χ2 by degrees of freedom (gl).19 A model demonstrates a reasonable fit if χ2/gl ≤ 3.

Although the main SEM model was performed in the overall sample including FEP and ARMS patients, we decided to include an additional exploratory analysis only in the subsample of the patients with a FEP. No analysis was performed including only patients with ARMS due to small sample size.

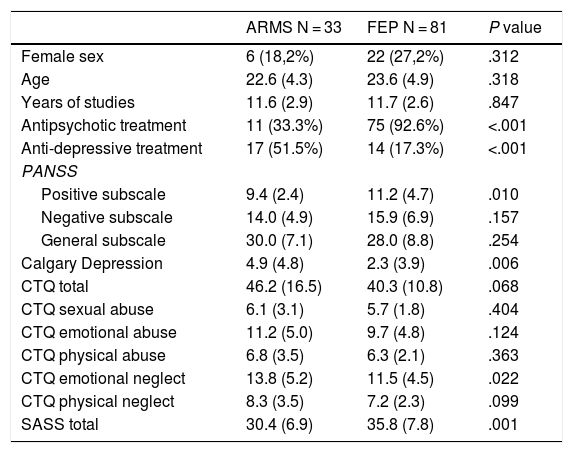

ResultsTable 1 shows the clinical characteristics, separated by diagnostic group (FEP vs. ARMS). There were no sociodemographic differences between the two groups. The patients with a FEP received antidepressant treatment more frequently. On a psychopathological level, the patients with a FEP presented more positive symptoms and the ARMS patients more depressive symptoms. Although there were no differences in total scores on the CTQ scale, the ARMS patients referred more frequently to a history of emotional neglect. Regarding the SASS scale, the patients with a FEP referred to better social adaptation, compared with the ARMS group.

Clinical sample characteristics.

| ARMS N = 33 | FEP N = 81 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 6 (18,2%) | 22 (27,2%) | .312 |

| Age | 22.6 (4.3) | 23.6 (4.9) | .318 |

| Years of studies | 11.6 (2.9) | 11.7 (2.6) | .847 |

| Antipsychotic treatment | 11 (33.3%) | 75 (92.6%) | <.001 |

| Anti-depressive treatment | 17 (51.5%) | 14 (17.3%) | <.001 |

| PANSS | |||

| Positive subscale | 9.4 (2.4) | 11.2 (4.7) | .010 |

| Negative subscale | 14.0 (4.9) | 15.9 (6.9) | .157 |

| General subscale | 30.0 (7.1) | 28.0 (8.8) | .254 |

| Calgary Depression | 4.9 (4.8) | 2.3 (3.9) | .006 |

| CTQ total | 46.2 (16.5) | 40.3 (10.8) | .068 |

| CTQ sexual abuse | 6.1 (3.1) | 5.7 (1.8) | .404 |

| CTQ emotional abuse | 11.2 (5.0) | 9.7 (4.8) | .124 |

| CTQ physical abuse | 6.8 (3.5) | 6.3 (2.1) | .363 |

| CTQ emotional neglect | 13.8 (5.2) | 11.5 (4.5) | .022 |

| CTQ physical neglect | 8.3 (3.5) | 7.2 (2.3) | .099 |

| SASS total | 30.4 (6.9) | 35.8 (7.8) | .001 |

The data represent mean (standard deviation) or N (%).

ARMS: At risk mental state; CTQ: Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; FEP: First psychotic episode; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SASS: Social Adaptation Self-evaluation Scale.

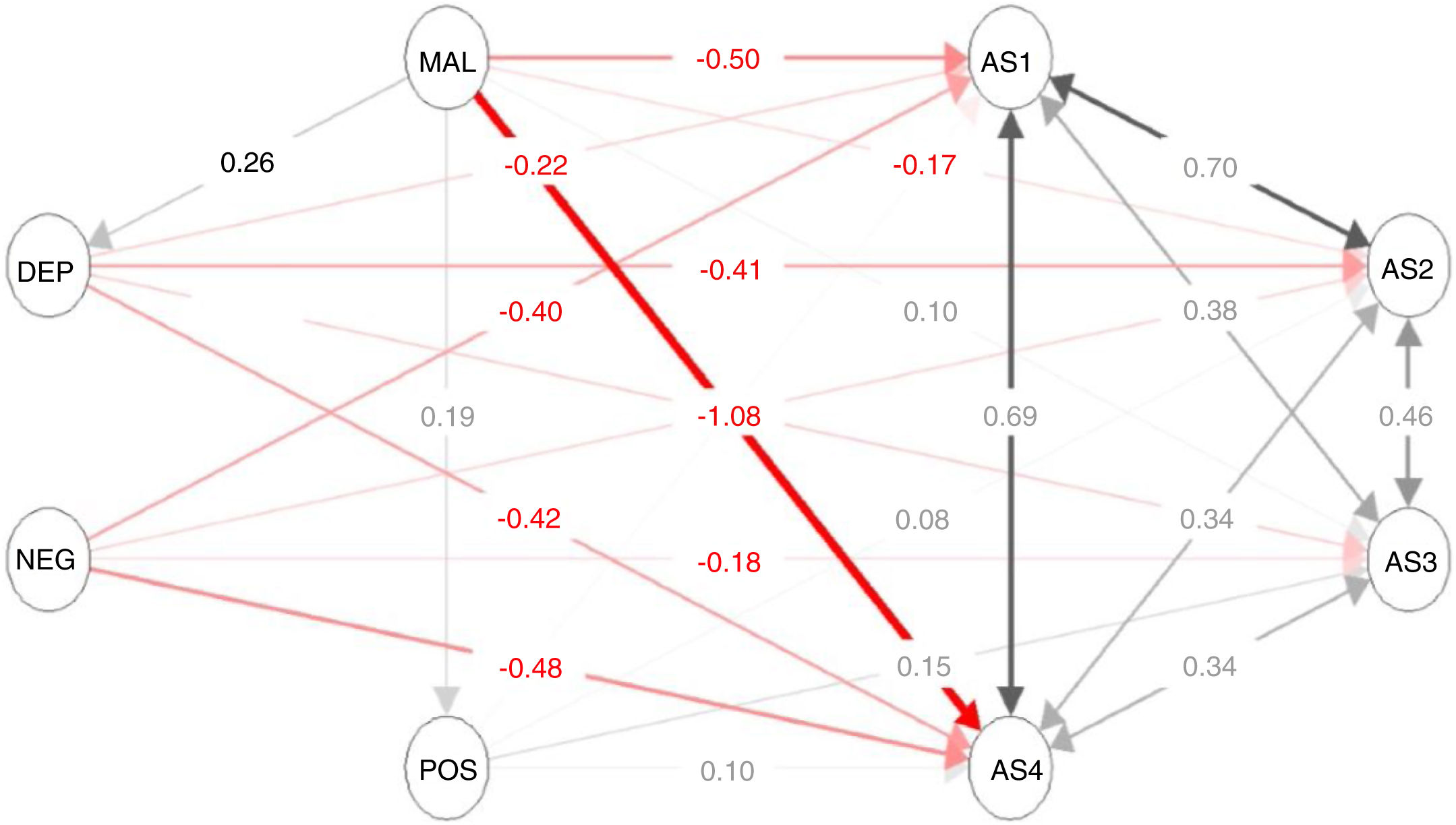

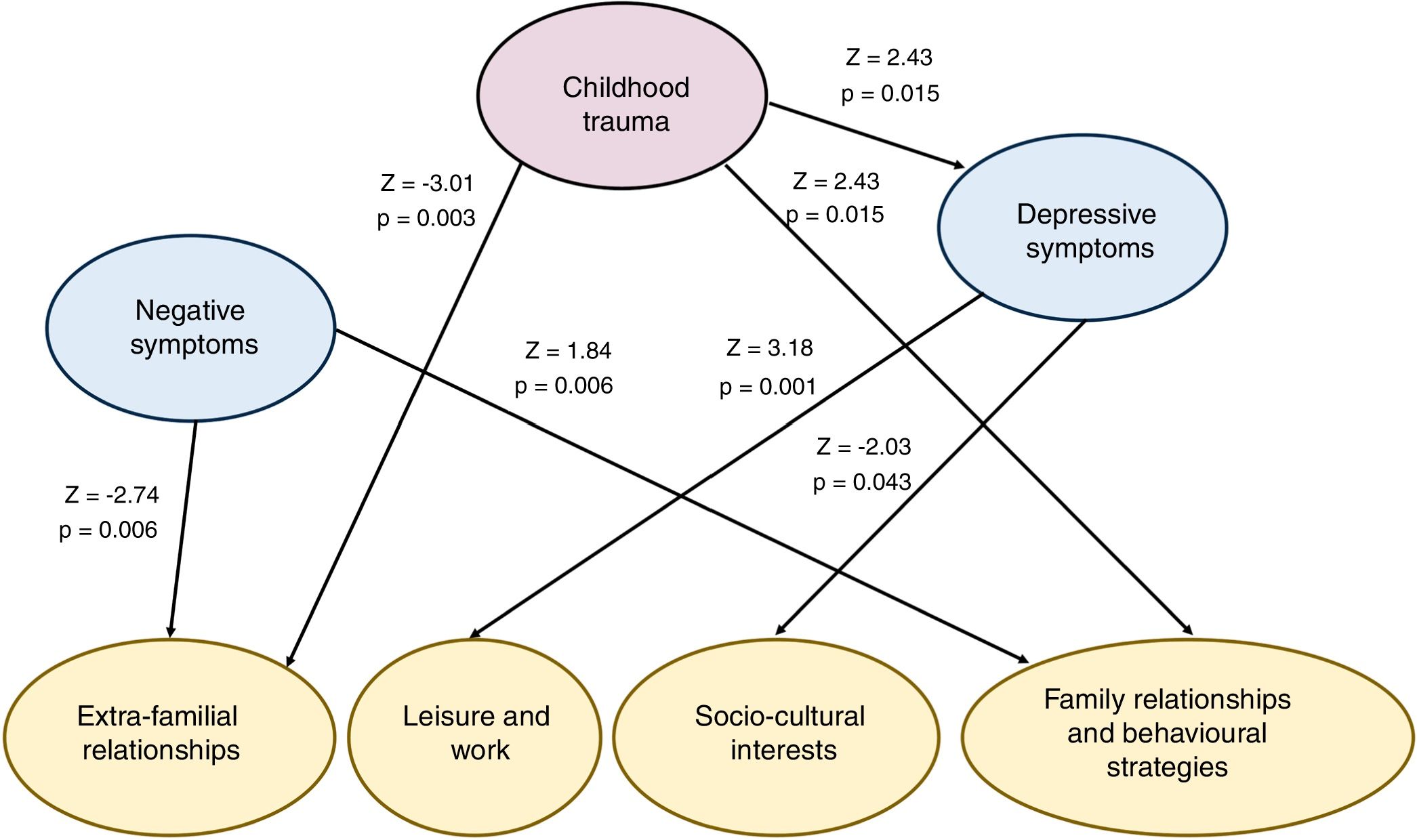

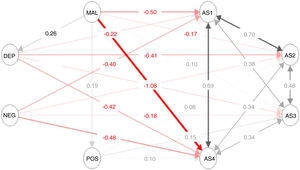

Overall SEM analysis (including FEP and ARMS patients jointly) is described in Fig. 1. The model presented a moderate fit assessed with the CFI (.821) index. Although the χ2 test was significant (P < .001), χ2 (gl = 535) was 782.4; and therefore the ratio χ2/gl was 1.5. As a result, the SEM model shows a reasonable fit. The SRMR was .102. The results of the equations of the SEM model may also be observed in Table 2. To better interpret the significant results of the equations of the SEM model visually, in Fig. 2 the significant relationships of the overall SEM model have been simplified indicating the standardised values (Z-scores) and P values of each regression which has been significant in the SEM model.

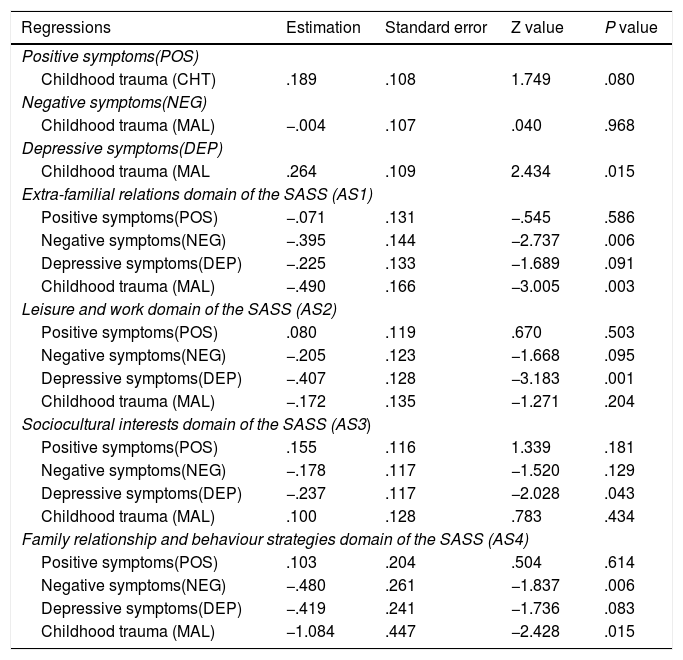

Relationship of the clinical variables, on childhood trauma and social adaptation using structural equation modelling in the overall sample.

The figure describes the relationship (estimated parameters) between latent variables which reflect different domains of psychopathology, childhood trauma or social adaption. Each latent variable is composed of different items or scales as defined in the section on methods. The variables which comprise each latent variable were not shown in the figure to facilitate data interpretation. AS1: extra-familial relationship domain of the SASS; AS2: leisure and work domain of the SASS; AS3: sociocultural interests domain of the SASS; AS4: family relationships and behavioural strategies domain of the SASS; DEP: depressive symptoms; CHT: childhood trauma; NEG: negative symptoms; POS: positive symptoms.

Result of the regressions between latent variables and variables depending on the SEM analysis performed in 114 patients with an ARMS or a FEP.

| Regressions | Estimation | Standard error | Z value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive symptoms(POS) | ||||

| Childhood trauma (CHT) | .189 | .108 | 1.749 | .080 |

| Negative symptoms(NEG) | ||||

| Childhood trauma (MAL) | −.004 | .107 | .040 | .968 |

| Depressive symptoms(DEP) | ||||

| Childhood trauma (MAL | .264 | .109 | 2.434 | .015 |

| Extra-familial relations domain of the SASS (AS1) | ||||

| Positive symptoms(POS) | −.071 | .131 | −.545 | .586 |

| Negative symptoms(NEG) | −.395 | .144 | −2.737 | .006 |

| Depressive symptoms(DEP) | −.225 | .133 | −1.689 | .091 |

| Childhood trauma (MAL) | −.490 | .166 | −3.005 | .003 |

| Leisure and work domain of the SASS (AS2) | ||||

| Positive symptoms(POS) | .080 | .119 | .670 | .503 |

| Negative symptoms(NEG) | −.205 | .123 | −1.668 | .095 |

| Depressive symptoms(DEP) | −.407 | .128 | −3.183 | .001 |

| Childhood trauma (MAL) | −.172 | .135 | −1.271 | .204 |

| Sociocultural interests domain of the SASS (AS3) | ||||

| Positive symptoms(POS) | .155 | .116 | 1.339 | .181 |

| Negative symptoms(NEG) | −.178 | .117 | −1.520 | .129 |

| Depressive symptoms(DEP) | −.237 | .117 | −2.028 | .043 |

| Childhood trauma (MAL) | .100 | .128 | .783 | .434 |

| Family relationship and behaviour strategies domain of the SASS (AS4) | ||||

| Positive symptoms(POS) | .103 | .204 | .504 | .614 |

| Negative symptoms(NEG) | −.480 | .261 | −1.837 | .006 |

| Depressive symptoms(DEP) | −.419 | .241 | −1.736 | .083 |

| Childhood trauma (MAL) | −1.084 | .447 | −2.428 | .015 |

ARMS: at risk mental state; FEP: first psychotic episode; SASS: Social Adaptation Self-evaluation Scale.

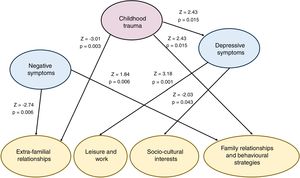

Significant relationships between childhood trauma, psychopathology and dimensions of social adaptation in the structural equations model in the overall sample.

Standardised scores shown (z-scores) of the relationships between latent variables of the structural equation modelling on the overall sample (including ARMSand FEP patients). The positive scores indicate positive association and the negative scores negative relationships. Given that the dimensions of social adaptation are made up of items form the SASS scale which with higher scores better reflect social adaptation, the negative scores of z-scores imply associations with poorer social functionality.

ARMS: at risk mental state; FEP: first psychotic episode; SASS: Social Adaptation Self-evaluation Scale.

SEM analysis shows that trauma is directly associated with a poorer social adaptation in domains which involve interpersonal relations: extra-familial relationships (Z = −3.01, P = .003) and family relationships and behavioural strategies (Z = −2.43, P = .015). However, the direct relationship in domains relating to leisure and sociocultural interest is not significant. The histories of childhood trauma are also associated with depressive symptoms (Z = 2.43, P = .015) but not with positive or negative symptoms. In turn, depressive symptoms are associated significantly with poor social adaptation in the leisure and work domains (Z = −3.18, P = .001) and sociocultural interests (Z = −2.03, P = .043), although not in the domains linked to interpersonal relationships. These results suggest that childhood trauma negatively affects the domains of social adaptation that involve interpersonal relationships “by a pathway mediated by depressive symptoms” in the dimensions of social adaptation related to leisure, work and sociocultural interest. The positive symptoms were not related to social adaptation. Negative symptoms were significantly associated with poorer social adaptation in extra-familial relationships (Z = −2,74, P = .006). This relationship between negative symptoms and social adaptation is separate from childhood trauma.

Secondary SEM analysis in the FEP subsample has been represented as Appendix B Appendix, supplementary material in figure S1 and table S2, with the graphic description of the significant results in figure S2. Considering CFI the parameters of fit are slightly poorer (CFI = .749; SRMR = .111; χ2 = 799,85; gl = 535; P < .001). However, the χ2/gl ratio is also 1.5, which suggests a reasonable fit. Regarding the associations between entre variables, there are slight differences of this analysis with the overall SEM analysis. For example, in the subsample of FEP childhood trauma is associated with positive symptoms and depressive symptoms in FEP (in the overall sample it is not associated with positive clinical symptoms). Positive symptoms continue not to be associated with any dimension of social adaptation. Negative symptoms are associated with poorer functionality in 3 of the 4 dimensions (leisure and work, sociocultural interests and family relationships and behavioural strategies). Depressive symptoms are associated with poorer functionality in the same dimensions as in the overall SEM model. Unlike the previous model, in the SEM model which only includes patients with a FEP, childhood trauma is not directly associated with poorer functionality, and the pathway mediated by depressive symptoms would be maintained.

DiscussionIn a sample of young people who were attending an Early Intervention Service for Psychosis for an ARMS or a FEP we observed that histories of childhood trauma had a negative effect on social adaptation directly in interpersonal relationships and mediated by depressive symptoms in activities which involved leisure, work and sociocultural interests. The negative symptoms were also associated with poorer social adaption in extra-familial relationships.

To date there is only one study that has used SEM analysis to explore the relationships between childhood trauma, psychopathological symptoms and functionality in patients with a psychotic disorder.21 In this study which included 54 patients (14 ARMS, 20 FEP and 20 chronic psychotic disorders) and 120 non clinical participants, the histories of early adversity were related to poorer functionality mediated by depressive symptoms. In this study, in theory, early adversity was not related to mental skills. Our study is in keeping with the study by Palmier-Claus et al.,21 but adds interesting aspects such as describing in greater detail the social adaptation component in dimensions. The direct effect of childhood trauma in the interpersonal relationships fits in with studies in the literature which suggest that early stress, including mistreatment or bullying is associated with a worse social adaptation in adult life.22 Other studies in patients with incipient psychotic disorder have shown there to be a relationship between childhood trauma and poorer social functionality, particularly if the stressful traumatic experiences occurred before the age of 11.23 Studies conducted in the general population which have studied potential psychological mechanisms which would explain the relationships between histories of childhood trauma and psychotic experiences suggest that adverse early experiences would be associated with maladaptative cognitive schemas and alterations of salience.24,25 These alterations in salience, also defined as the assignment of a relevance,26 would involve the incorrect assignment of significance or relevance to innocuous stimuli. This psychological mechanism could explain the difficulties of social adaptation in situations which involved interpersonal relationships. Previous studies in aptness with psychotic disorders have shown that a history of childhood trauma,27 and in particular sexual abuse,28,29 has been associated with difficulties in emotional processing, which could also interfere with interpersonal relationships. In contrast, in those activities more focused on the activity itself (leisure, sociocultural interests), childhood trauma plays a role through a pathway mediated by depressive symptoms. This pathway may be explained by the probable negative impact of the anhedonia in this type of activities.

The hypothesis of social defeat in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia suggests that some stressful situations with a social exclusion component and possible humiliation, which could be childhood trauma, would contribute to the risk of developing a psychosis in vulnerable subjects.7 In one study30 which analysed the possible mediating role of social defeat in the relationship between childhood trauma and psychotic phenotype in the general population (psychotic experiences) and patients with a psychotic disorder, a mediating role of social defeat in both population groups was observed although in the population sample (psychotic experiences as the dependent variable), emotional isolation was a second independent mediator. Histories of childhood trauma were associated with a higher risk of depressive symptomatology31,32 and poorer functional prognosis in patients with a psychotic disorder,5,32 in line with the results of our study.

One of the strengths of our study is that it is the first in the Spanish population to evaluate the relationship between childhood trauma, psychopathology and social adaptation in a representative sample of young people who were attending an early intervention service for psychosis. It also offers the originality of the use of a SEM model for simultaneous analysis of psychopathological variables, childhood trauma and social adaptation dimensions. Analysis with a SEM model means that the relationships between variables could be explored to avoid problems of co-lineality that could exist in other statistical techniques, such as in multiple lineal regressions. In our study it is of particular importance because different psychopathological dimensions and social adaption may correlate between them.

Some methodological decisions and limitations of our study may be commented upon. First, we decided to use a sample that includes both ARMS patients and patients with a FEP. This we mainly conducted because both groups of patients attended the PAE-TPI programmes in Catalonia. Also, both groups of patients were comparable in sociodemographic variables and although there were differences in social adaptation, the ARMS patients expressed poorer social adaptation. This could have been explained by the drop in functionality being one of the criteria of ARMS in one of the study subtypes. Since the sample size was relatively small, we did not wish to divide the sample into two to carry out a first exploratory SEM analysis and another validation analysis. Although our results replicated other studies which used the same methodology to explore the relationship between childhood trauma, depressive symptoms and functionality,21 it would be recommendable to replicate our study in the Spanish population. We did decide to include an additional, exploratory SEM analysis which only included the FEP sample. This sub analysis is similar to the global one with several different outcomes such as the association between childhood trauma and psychotic symptomatology, the association of negative symptoms with poorer functionality in more dimensions of social adaptation and the depressive effects associated with poorer social adaptation only by a mediated pathway (without direct effects). Notwithstanding, it is important to highlight that the sample size was lower than the one for the overall SEM, and that before obtaining final conclusion it would be advisable to replicate our results in larger samples of patients with a FEP. With regard to the use of the SASS, an initially developed scale for evaluated social adaptation in patients with depression, we opted to use it because one previous study in ARMS showed there to be a clear correlation with quality of life.9 It is important to point out that the cross-sectional design of our study did not offer inferences of causality, and longitudinal studies may solve this limitation in the future. Finally, the evaluation of the histories of childhood trauma with a self-applied tool could involve memory bias. Another limitation of the CTQ is that it does not allow for the evaluation of the developmental moment after the childhood trauma, which, as has already been commented upon, could determine the impact in social functionality.23

ConclusionsThe results obtained emphasize the importance of assessing histories of childhood trauma in clinical practice and intervening early on to improve the social functionality of young people at risk of developing a psychosis or with a FEP. The mediation by depressive symptoms of the negative effects of childhood trauma in other activities related to leisure and work also indicate the need to explore the existence of depressive symptoms in the young population who present for consultation with psychotic experiences in order to carry out specific interventions to improve the functionality of these patients.

FinancingThis study Project was financed by La Marató of TV3 (092230/092231) and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS, PI10/01607).

Laura Ortega received a PERIS grant for intensification in research (SLT002/0016/0125) from the Department of health of the Generalitat de Catalunya in 2017. Javier Labad received funds from the PERIS grant for intensification in research (SLT006/17/ 00012) Department of health of the Generalitat de Catalunya in 2018 and in 2019. Itziar Montalvo received a PERIS grant for intensification in research (SLT008/18/00074) from the Department of health of the Generalitat de Catalunya for 2019–2021.

Author/collaboratorsJL and LO contributed to the design and development of the study. JL performed statistical analyses. IM, MC, AC, MS collaborated in the assessment of patients and data collection and processing. The first manuscript was written by LO and JL, and the other authors contributed in the draft review and critical reading. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the participants upon which this study is based. Also to the Research Area of the institution, for their contributions and support during research.

Please cite this article as: Ortega L, Montalvo I, Solé M, Creus M, Cabezas Á, Gutiérrez-Zotes A, et al. Relación entre el maltrato infantil y la adaptación social en una muestra de jóvenes atendidos en un servicio de intervención precoz en psicosis. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2020;13:131–139.