Psychosocial functioning in patients with schizophrenia attended in daily practice is an understudied aspect. The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between symptomatic and psychosocial remission and adherence to treatment in schizophrenia.

MethodsThis cross-sectional, non-interventional, and multicenter study assessed symptomatic and psychosocial remission and community integration of 1787 outpatients with schizophrenia attended in Spanish mental health services. Adherence to antipsychotic medication in the previous year was categorized as ≥80% vs. <80%.

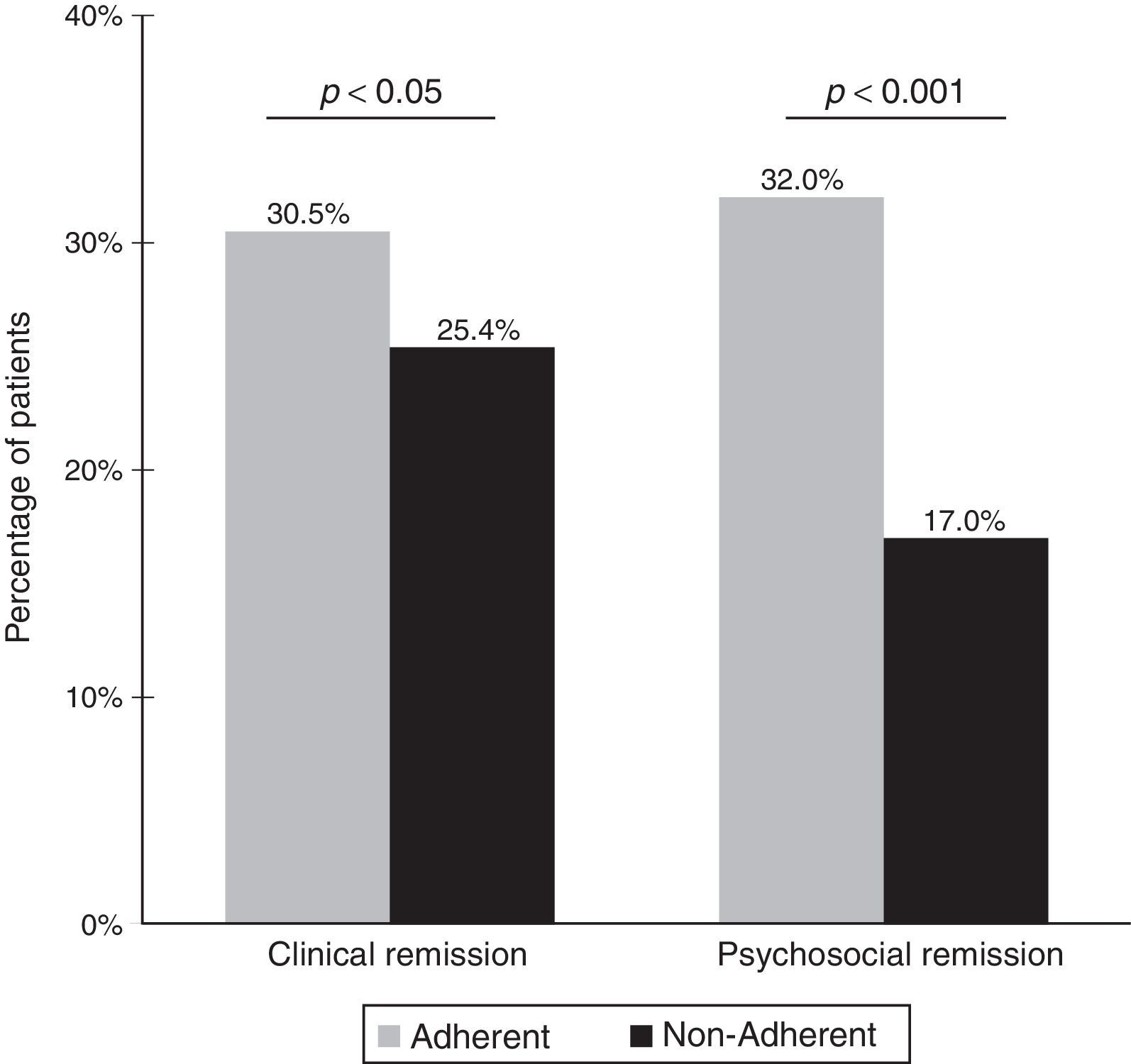

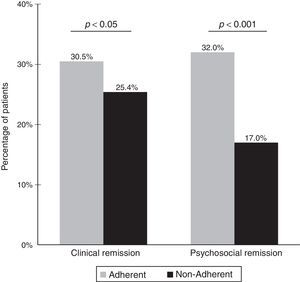

ResultsSymptomatic remission was achieved in 28.5% of patients, and psychosocial remission in 26.1%. A total of 60.5% of patients were classified as adherent to antipsychotic treatment and 41% as adherent to non-pharmacological treatment. During the index visit, treatment was changed in 28.4% of patients, in 31.1% of them because of low adherence (8.8% of the total population). Adherent patients showed higher percentages of symptomatic and psychosocial remission than non-adherent patients (30.5 vs. 25.4%, p<0.05; and 32 vs. 17%, p<0.001, respectively). Only 3.5% of the patients showed an adequate level of community integration, which was also higher among adherent patients (73.0 vs. 60.1%, p<0.05).

ConclusionsAdherence to antipsychotic medication was associated with symptomatic and psychosocial remission as well as with community integration.

El funcionamiento psicosocial en pacientes con esquizofrenia que son atendidos en la práctica diaria es un aspecto que no está suficientemente estudiado. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la relación entre la remisión sintomática y psicosocial y la adherencia al tratamiento en esquizofrenia.

MétodosEste estudio transversal, no intervencionista y multicéntrico evaluó la remisión sintomática y psicosocial y la integración comunitaria de 1.787 pacientes ambulatorios con esquizofrenia atendidos en servicios de salud mental españoles. La adherencia a la medicación antipsicótica en el año anterior se dividió en las categorías≥80% y<80%.

ResultadosLa remisión sintomática se alcanzó en el 28,5% de los pacientes, y la remisión psicosocial en el 26,2%. En total, el 60,5% de los pacientes se clasificaron dentro de la categoría de pacientes con adherencia al tratamiento antipsicótico y el 41% dentro de la de pacientes con adherencia al tratamiento no farmacológico. Durante la visita de estudio, se cambió el tratamiento al 28,4% de los pacientes, en el 31,1% debido a la baja adherencia (8,8% de la población total). Los pacientes con adherencia al tratamiento presentaron mayores porcentajes de remisión sintomática y psicosocial que aquellos sin adherencia (30,5 frente al 25,4%, p<0,05; y 32 frente al 17%, p<0,001, respectivamente). Solo el 3,5% de los pacientes presentaron un nivel adecuado de integración comunitaria, que también fue más alta entre los pacientes adherentes (73,0 frente al 60,1%, p<0,05).

ConclusionesLa adherencia al tratamiento antipsicótico se asoció con la remisión sintomática y psicosocial, así como con la integración comunitaria.

Community integration is a complex concept that encompasses physical, psychological and social dimensions1 and can be understood from different perspectives. For patients with severe mental illness, community integration is considered not only a challenge and an important goal to achieve but also an essential component of recovery.2

In schizophrenia, complete recovery implies not only the ability to achieve symptomatic remission and prevent relapse3 but also to attain an optimal level of functioning in the community from a social and occupational perspective4–9 (in this respect, Barak and co-workers10 developed the Psychosocial Remission in Schizophrenia Scale (PSRS), which complements symptomatic assessment of remission). There is increasing evidence concerning the positive effect of vocational rehabilitation programs and integration on the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia.11–13 Nevertheless, persistence of profound impairments across multiple domains of functioning after clinical stabilization have been described in several studies and settings.14

Adherence to antipsychotic medication is recognized to be crucial for symptomatic remission and relapse prevention in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia,15–17 though its importance for psychosocial remission has been much less studied. Related to both symptomatic and psychosocial remission, poor insight has been recognized as a predictor of non-compliance and a risk factor for relapse and, therefore, an impediment to effective patient management.18 Moreover, impaired insight has also been related to deficits in work function.19

Despite recent progress in our understanding and management of schizophrenia, there are several areas that remain understudied. On one hand, there is little evidence on the relationship between treatment adherence and psychosocial remission or society integration. This seems incongruent with the increasingly high importance that these factors are given in treatment of schizophrenia. On the other hand, a comprehensive assessment of psychosocial functioning in patients with schizophrenia attended in daily practice conditions, using specific rating scales, remains understudied and underutilized.20

The present study aimed to address both of these questions and was designed to assess the relationship between symptomatic and psychosocial remission and adherence to antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia attended in daily practice. We hypothesized that treatment adherence, as opposed to non-adherence, in ambulatory patients with schizophrenia would be associated with higher rates of both clinical and psychosocial remission and patient's integration into society.

MethodsStudy designAn epidemiological, cross-sectional, non-interventional, and multicenter study was designed to assess symptomatic and psychosocial remission in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder according to the degree of adherence to antipsychotic medication. Assessment of community integration, factors associated with symptomatic remission, psychosocial remission, and evaluation of the effect of premorbid adjustment and level of insight on symptomatic remission, psychosocial remission and community integration were also evaluated.

PatientsBetween November 2010 and August 2011, consecutive patients diagnosed of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to DSM-IV-TR criteria21 who visited the outpatient mental health clinics and met the selection criteria were enrolled into this study. The clinician in charge had to have access to the patient's medical history and had to be able to determine the degree of compliance with antipsychotic medication during the past 2 years, based on the self-reported information given by patients and caregivers. Patients who had required admission to acute-care psychiatric/short stay units over the previous 12 months were not eligible, as well as those diagnosed with severe mental illnesses other than schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, severe or moderate mental deterioration or any personality disorder and/or severe neurological disease and/or incapacitating disease.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona (Spain) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (version 1989) and its amendments.22 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or legal guardians prior to enrollment in the study.

Study procedures and data collectionThis study was carried out in Mental Health Centers and Outpatient Mental Health Facilities in Spain that met the requirements to perform the present study in the feasibility process and had the required patient population. A total of 125 sites from 14 Autonomous Communities participated. To ensure a national level of representation, a proportional number of physicians in relation to the total number of physicians in each Autonomous Community was selected. All participating investigators were psychiatrists. All of them received training in study procedures and correct usage of scales in order to minimize inter-rater differences during the evaluation process.

The study included a single clinical visit (index visit) in which sociodemographic data, socio-familial variables, occupation and autonomy-related variables and clinical data were recorded.

Sociodemographic variables were age, sex, ethnicity and attitude during the interview (very cooperative, partially cooperative, indifferent, suspicious, hostile). Socio-familial variables included marital status; familial expressed emotion (an ad-hoc developed likert-type scale based on criticism, hostility, and emotional over-involvement rating expressed emotion as absent, low, moderate, high or very high); family support; living conditions; time devoted by the main caregiver; and the general scale of the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS).23,24 Occupation and autonomy-related variables included current occupation status (unemployed, employed, socially protected employment, employed in a special center, enterprise labor insertion), as well as attendance of occupation centers or training programs, attempts to find employment (never, rarely, sometimes, often) and capability of doing work (no, yes, hardly could do some work).

Clinical data included type of schizophrenia; duration of disease; number of psychiatric hospitalizations; history of substance use; clinical impression of cognitive impairment (categorized as none, mild, moderate, severe in an ad-hoc developed questionnaire); current Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGI-S) scale25 score; pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment in the previous 12 months; current pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment; the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)26 score; adherence to antipsychotic medication in the previous year (categorized by the clinician as adherent if compliance was ≥80% and non-adherent if compliance was <80%)27 based on the information given by patients and caregivers; patient-reported satisfaction with treatment (Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire, MSQ)28–30; level of insight using the general items of the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD)31; symptomatic remission using the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group criteria3 that included 8 items (delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, blunted affect, social withdrawal, lack of spontaneity, mannerisms/posturing, and unusual thought content); and psychosocial remission using the PSRS scale10 that included 8 items (familial relations, understanding and self-awareness, energy, interest in everyday life, self-care, activism, responsibility for medications, and use of community services).

Because of the lack of a consensus definition regarding community integration in schizophrenia, a composite approach was developed specifically for this study, which was based on the concepts traditionally used for evaluating community integration, such as occupation, support, acceptance and independence.32 Community integration was a composite variable that included the presence of symptomatic remission (assessed by the physician taking into account the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group criteria, and considering symptomatic remission if the patient has a score of absent, minimal or mild for the 8 items and this has been maintained during the last 8 months); psychosocial remission, affirmative answer to capability of doing work, and “sometimes” or “often” answer for attempts to find employment (information collected via interview between physician and patient).

Sample size and statistical analysisTaking into account that the prevalence of schizophrenia in Spain is 1% and that approximately 50% of patients are on treatment, the total number of subjects attended at Mental Health Centers is about 230,789.33 Assuming that there are various reasons for treatment discontinuation (e.g., lack of satisfaction with treatment, poor symptom control, adverse events, complex medication schedules, etc.) and that the clinician will decide in each case whether the patient is adherent or non-adherent (clinical judgment with the information reported by the patient and caregiver),34 for a maximum indetermination level (p=50%), a sample size of 1784 patients was necessary for an estimate of ±2% at the 95% confidence interval (CI). Participating physicians at each Mental Health Center included the first 10 consecutive patients who met the inclusion criteria and gave written informed consent.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 for Windows was used for the analysis of data.35 The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normal distribution of data. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or as median and interquartile range (IQR) (25–75th percentile), and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The Student's t test or the Mann–Whitney U test were used for the analysis of quantitative variables, and the chi-square (χ2) test or the Fisher's exact probability test for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess variables independently associated with symptomatic remission, psychosocial remission, and level of community integration. Selection of variables used in the regression model was done via automated stepwise processes of sequential inclusion and exclusion. A significance level of 0.05 was considered for all statistical tests.

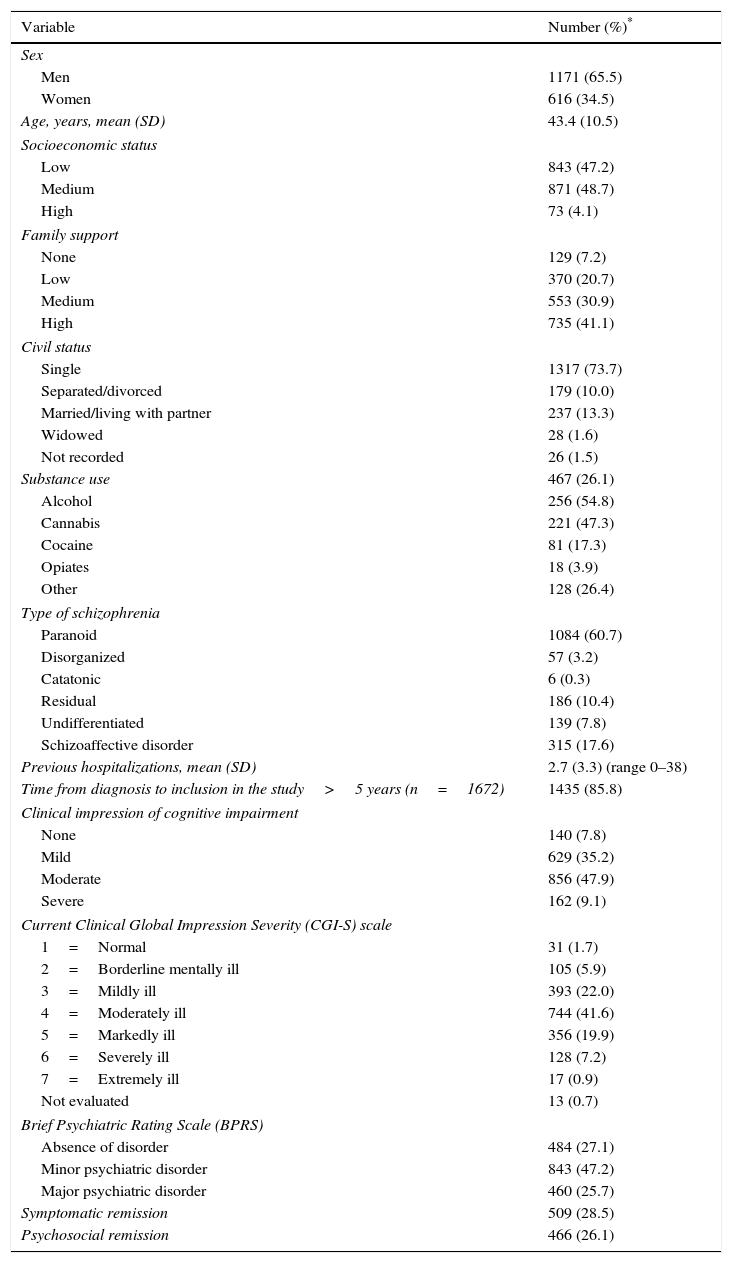

ResultsPopulation characteristicsOut of the 1809 patients that were recruited during the study period, 22 (1.2%) were excluded for the following reasons: missing data (n=18), incomplete data (n=1), no previous use of at least one antipsychotic drug (n=1), and lack of fulfillment of the inclusion criteria (n=1). Therefore, the study population included 1787 patients with a mean age of 43.4 (SD=10.5) years.

Salient sociodemographic data and socio-familial variables are shown in Table 1. Familial expressed emotion was low in 36.1% of patients, moderate in 33.8%, high in 16.6%, and very high in 2.9%. Also, 59.6% had a very cooperative attitude during the interview. A total of 1375 (76.9%) patients were unemployed and 63.3% had a certificate of incapacity for work. The majority of patients almost never attended occupational centers (68.5%) or occupational training courses (71.3%). To the question “Do you think that you are able to perform some kind of work?”, only 28.1% of patients answered affirmatively. Regarding “How often do you try to find a job?” only 9.4% and 7% answered sometimes or often, respectively.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 1787 patients included in the study.

| Variable | Number (%)* |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Men | 1171 (65.5) |

| Women | 616 (34.5) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 43.4 (10.5) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Low | 843 (47.2) |

| Medium | 871 (48.7) |

| High | 73 (4.1) |

| Family support | |

| None | 129 (7.2) |

| Low | 370 (20.7) |

| Medium | 553 (30.9) |

| High | 735 (41.1) |

| Civil status | |

| Single | 1317 (73.7) |

| Separated/divorced | 179 (10.0) |

| Married/living with partner | 237 (13.3) |

| Widowed | 28 (1.6) |

| Not recorded | 26 (1.5) |

| Substance use | 467 (26.1) |

| Alcohol | 256 (54.8) |

| Cannabis | 221 (47.3) |

| Cocaine | 81 (17.3) |

| Opiates | 18 (3.9) |

| Other | 128 (26.4) |

| Type of schizophrenia | |

| Paranoid | 1084 (60.7) |

| Disorganized | 57 (3.2) |

| Catatonic | 6 (0.3) |

| Residual | 186 (10.4) |

| Undifferentiated | 139 (7.8) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 315 (17.6) |

| Previous hospitalizations, mean (SD) | 2.7 (3.3) (range 0–38) |

| Time from diagnosis to inclusion in the study>5 years (n=1672) | 1435 (85.8) |

| Clinical impression of cognitive impairment | |

| None | 140 (7.8) |

| Mild | 629 (35.2) |

| Moderate | 856 (47.9) |

| Severe | 162 (9.1) |

| Current Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGI-S) scale | |

| 1=Normal | 31 (1.7) |

| 2=Borderline mentally ill | 105 (5.9) |

| 3=Mildly ill | 393 (22.0) |

| 4=Moderately ill | 744 (41.6) |

| 5=Markedly ill | 356 (19.9) |

| 6=Severely ill | 128 (7.2) |

| 7=Extremely ill | 17 (0.9) |

| Not evaluated | 13 (0.7) |

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) | |

| Absence of disorder | 484 (27.1) |

| Minor psychiatric disorder | 843 (47.2) |

| Major psychiatric disorder | 460 (25.7) |

| Symptomatic remission | 509 (28.5) |

| Psychosocial remission | 466 (26.1) |

Table 1 also shows salient clinical features of the patients. Clinical impression of cognitive impairment was moderate in 47.9% of patients and mild in 35.2%. In relation to the CGI-S, the most frequent categories were “moderately ill” (41.6%), “mildly ill” (22.0%), and “markedly ill” (19.9%) (Table 1). In relation to the BPRS, 25.7% of patients had a major psychiatric disorder and 47.2% a minor psychiatric disorder. Symptomatic remission was recorded in 28.5% of patients and psychosocial remission in 26.1%. The mean (SD) level of insight (SUMD) was 2.3 (1.2) for awareness of mental disorder, 2.1 (1.2) for awareness of need for treatment, and 2.3 (1.3) for awareness of the social consequences of the disorder. The mean (SD) PAS score was 25.5 (9.4).

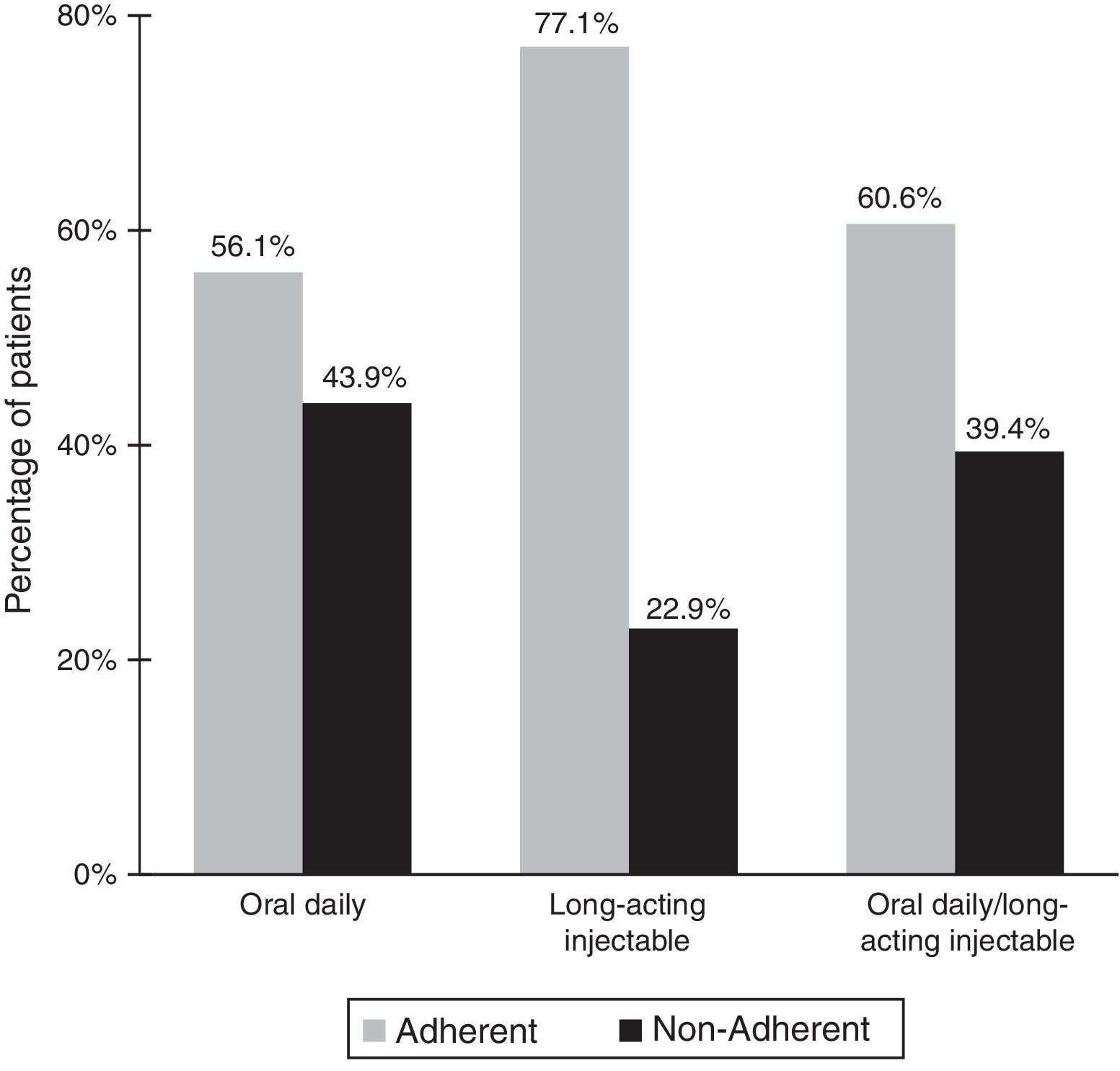

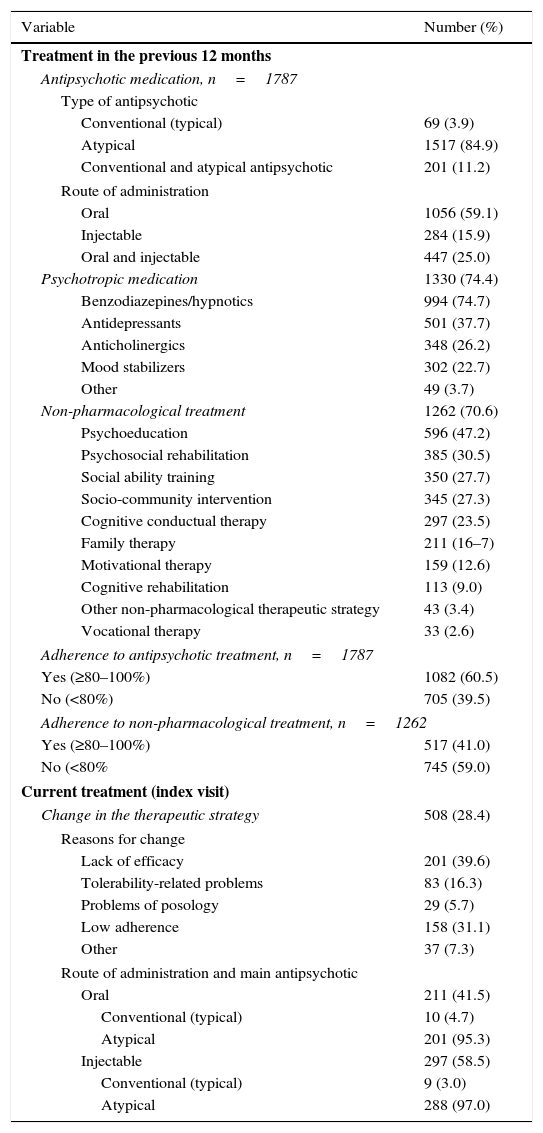

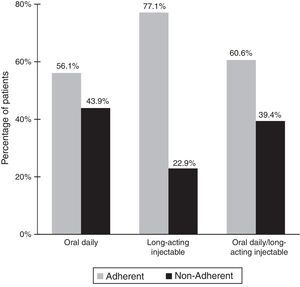

Treatment-related dataAs shown in Table 2, all patients were treated with antipsychotic drugs for the previous 12 months. Most patients (84.9%) were treated with atypical antipsychotics. In relation to the route of administration, the oral route was the most frequent (59.1%). Other psychotropic medication was also recorded in 74.4% of the patients, 74.7% of whom received benzodiazepines/hypnotics. A total of 60.5% of patients were classified as adherent to antipsychotic treatment and 41% as adherent to non-pharmacological treatment. As shown in Fig. 1 there was a statistically significant relationship (p<0.001) between adherence to treatment and the route of administration of antipsychotic agents. The rate of adherence was 77.1% (219/284) for injectable medications, 56.1% (592/1056) for the oral route, and 60.6% (271/447) for the combination of oral and injectable routes.

Previous and current treatment-related data.

| Variable | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Treatment in the previous 12 months | |

| Antipsychotic medication, n=1787 | |

| Type of antipsychotic | |

| Conventional (typical) | 69 (3.9) |

| Atypical | 1517 (84.9) |

| Conventional and atypical antipsychotic | 201 (11.2) |

| Route of administration | |

| Oral | 1056 (59.1) |

| Injectable | 284 (15.9) |

| Oral and injectable | 447 (25.0) |

| Psychotropic medication | 1330 (74.4) |

| Benzodiazepines/hypnotics | 994 (74.7) |

| Antidepressants | 501 (37.7) |

| Anticholinergics | 348 (26.2) |

| Mood stabilizers | 302 (22.7) |

| Other | 49 (3.7) |

| Non-pharmacological treatment | 1262 (70.6) |

| Psychoeducation | 596 (47.2) |

| Psychosocial rehabilitation | 385 (30.5) |

| Social ability training | 350 (27.7) |

| Socio-community intervention | 345 (27.3) |

| Cognitive conductual therapy | 297 (23.5) |

| Family therapy | 211 (16–7) |

| Motivational therapy | 159 (12.6) |

| Cognitive rehabilitation | 113 (9.0) |

| Other non-pharmacological therapeutic strategy | 43 (3.4) |

| Vocational therapy | 33 (2.6) |

| Adherence to antipsychotic treatment, n=1787 | |

| Yes (≥80–100%) | 1082 (60.5) |

| No (<80%) | 705 (39.5) |

| Adherence to non-pharmacological treatment, n=1262 | |

| Yes (≥80–100%) | 517 (41.0) |

| No (<80% | 745 (59.0) |

| Current treatment (index visit) | |

| Change in the therapeutic strategy | 508 (28.4) |

| Reasons for change | |

| Lack of efficacy | 201 (39.6) |

| Tolerability-related problems | 83 (16.3) |

| Problems of posology | 29 (5.7) |

| Low adherence | 158 (31.1) |

| Other | 37 (7.3) |

| Route of administration and main antipsychotic | |

| Oral | 211 (41.5) |

| Conventional (typical) | 10 (4.7) |

| Atypical | 201 (95.3) |

| Injectable | 297 (58.5) |

| Conventional (typical) | 9 (3.0) |

| Atypical | 288 (97.0) |

In relation to satisfaction with treatment, 36.3% of patients were very satisfied, 23.1% somewhat satisfied, 20.4% neither dissatisfied nor satisfied, 11.9% somewhat dissatisfied, and 4.8% very dissatisfied.

During the index visit, the therapeutic strategy (pharmacological or non-pharmacological) was changed in 508 (28.4%) patients. In 39.6% of cases, treatment was changed because of lack of efficacy (Table 2). Low adherence was the reason for change in 31.1% of patients (8.8% of the total population). Among the 508 patients in which the therapeutic strategy was modified, atypical antipsychotics were prescribed in 95.3% of patients and long-acting formulations in 97.0%. Also, a change in non-pharmacological management was recorded in 93.1% (473/508) of the patients, including the indication of psychoeducation in 48.4%, socio-community intervention in 28.5%, psychosocial rehabilitation in 27.9%, social ability training in 25.8%, cognitive conductual therapy in 24.9%, family therapy in 16.9%, motivational therapy in 12.3%, and cognitive rehabilitation in 11.8%.

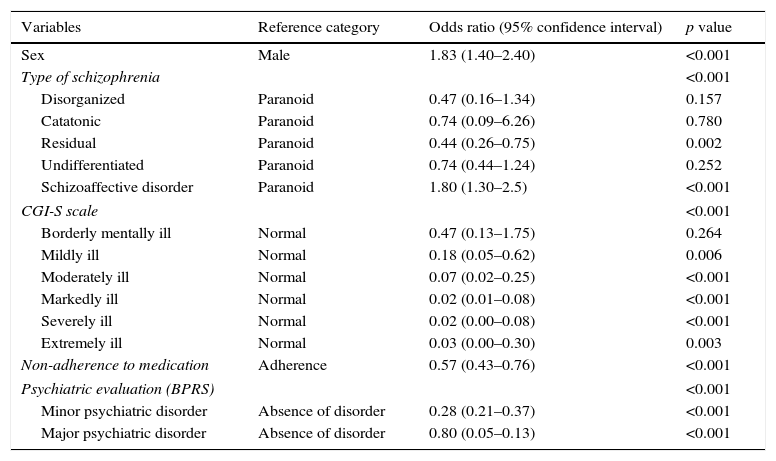

Symptomatic remissionOverall, 28.5% of patients (509/1787) had symptomatic remission. As shown in Fig. 2, the percentage of patients with symptomatic remission was significantly higher among patients who were adherent to antipsychotic medication (30.5%) than among non-adherent patients (25.4%) (p<0.05). Differences in the percentages of patients with symptomatic remission between the adherent and non-adherent groups were statistically significant for 6 of the 8 items of the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group criteria. Also, patients with symptomatic remission as compared to those without symptomatic remission showed lower mean PAS scores (20.7 [7.8] vs 27.4 [9.4], p<0.001) and insight levels for awareness of mental disorder (1.7 [1.0] vs 2.5 [1.3], p<0.001), awareness of need for treatment (1.6 [0.9] vs 2.3 [1.2], p<0.001), and awareness of the social consequences of the disorder (1.8 [1.1] vs 2.5 [1.3], p<0.001). In the bivariate analysis, factors significantly associated with symptomatic remission were age, sex, main psychiatric diagnosis, CGI-S category, adherence, and psychiatric evaluation. In the multivariate analysis, the probability of symptomatic remission was significantly higher among women, patients diagnosed of paranoid schizophrenia, adherent to medication, and in the categories of CGI-S “normal” and BPSR “absence of disorder” (Table 3).

Independent factors associated with symptomatic remission in the multivariate analysis.

| Variables | Reference category | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1.83 (1.40–2.40) | <0.001 |

| Type of schizophrenia | <0.001 | ||

| Disorganized | Paranoid | 0.47 (0.16–1.34) | 0.157 |

| Catatonic | Paranoid | 0.74 (0.09–6.26) | 0.780 |

| Residual | Paranoid | 0.44 (0.26–0.75) | 0.002 |

| Undifferentiated | Paranoid | 0.74 (0.44–1.24) | 0.252 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | Paranoid | 1.80 (1.30–2.5) | <0.001 |

| CGI-S scale | <0.001 | ||

| Borderly mentally ill | Normal | 0.47 (0.13–1.75) | 0.264 |

| Mildly ill | Normal | 0.18 (0.05–0.62) | 0.006 |

| Moderately ill | Normal | 0.07 (0.02–0.25) | <0.001 |

| Markedly ill | Normal | 0.02 (0.01–0.08) | <0.001 |

| Severely ill | Normal | 0.02 (0.00–0.08) | <0.001 |

| Extremely ill | Normal | 0.03 (0.00–0.30) | 0.003 |

| Non-adherence to medication | Adherence | 0.57 (0.43–0.76) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric evaluation (BPRS) | <0.001 | ||

| Minor psychiatric disorder | Absence of disorder | 0.28 (0.21–0.37) | <0.001 |

| Major psychiatric disorder | Absence of disorder | 0.80 (0.05–0.13) | <0.001 |

| Cox & Snell R Square | Nagelkerke R Square |

|---|---|

| 0.302 | 0.433 |

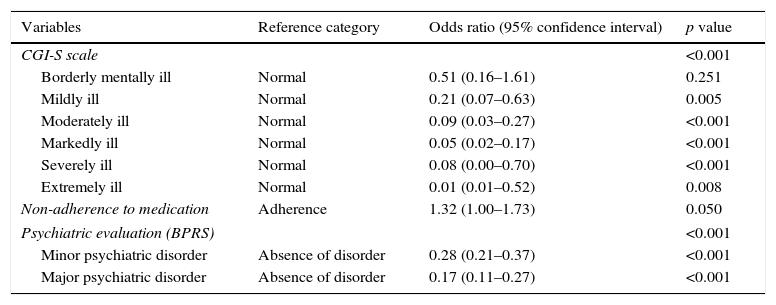

Overall, psychosocial remission was achieved in 26.1% (466/1787) of the patients. There was a statistically significant relationship between adherence to treatment and psychosocial remission. The percentage of patients with psychosocial remission was significantly higher in the adherent group than in the non-adherent group (32% vs 17%, p<0.001) (Fig. 2). Differences in the percentages of patients with psychosocial remission according to presence or absence of adherence to antipsychotic medication were also significant for all individual items of the PSRS scale. Lower mean PAS scores were also observed in patients with psychosocial remission (20.7 [8.5]) than in those without psychosocial remission (27.2 [9.2]) (p<0.001). Moreover, patients with psychosocial remission showed higher insight levels for awareness of mental disorder (lower SUMD scores) (1.7 [1.1] vs 2.5 [1.2], p<0.001), awareness of need for treatment (1.5 [0.9] vs 2.3 [1.2], p<0.001), and awareness of the social consequences of the disorder (1.7 [1.1] vs 2.5 [1.3], p<0.001). In the bivariate analysis, main psychiatric diagnosis (p<0.001), CGI-S category (p<0.001), adherence (p<0.001), and psychiatric evaluation (p<0.001) were significantly associated with psychosocial remission. In the multivariate analysis (Table 4), independent factors associated with psychosocial remission were adherence to antipsychotic treatment and in the categories of CGI-S “normal” and BPSR “absence of disorder”.

Independent factors associated with psychosocial remission in the multivariate analysis.

| Variables | Reference category | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGI-S scale | <0.001 | ||

| Borderly mentally ill | Normal | 0.51 (0.16–1.61) | 0.251 |

| Mildly ill | Normal | 0.21 (0.07–0.63) | 0.005 |

| Moderately ill | Normal | 0.09 (0.03–0.27) | <0.001 |

| Markedly ill | Normal | 0.05 (0.02–0.17) | <0.001 |

| Severely ill | Normal | 0.08 (0.00–0.70) | <0.001 |

| Extremely ill | Normal | 0.01 (0.01–0.52) | 0.008 |

| Non-adherence to medication | Adherence | 1.32 (1.00–1.73) | 0.050 |

| Psychiatric evaluation (BPRS) | <0.001 | ||

| Minor psychiatric disorder | Absence of disorder | 0.28 (0.21–0.37) | <0.001 |

| Major psychiatric disorder | Absence of disorder | 0.17 (0.11–0.27) | <0.001 |

| Cox & Snell R Square | Nagelkerke R Square |

|---|---|

| 0.237 | 0.348 |

Only 3.5% of the patients showed an adequate level of community integration. Community integrated patients, compared to patients without community integration, showed lower SUMD scores for awareness of mental disorder (1.5 [0.8] vs 2.3 [1.2], p<0.001), awareness of need for treatment (1.4 [0.7] vs 2.1 [1.2], p<0.001), and awareness of the social consequences of the disorder (1.6 [0.8] vs 2.3 [1.3], p<0.001), which means higher insight levels in these patients. Also, community integrated patients showed significantly lower mean values of the PAS score (19.4 [6.3]) than patients without community integration (25.7 [9.4] (p<0.001).

In the bivariate analysis, presence of community integration, as compared to absence of community integration, was associated with younger age (mean 35.5 [8.7] vs 43.7 [10.5] years, p<0.001), main diagnosis (p<0.05), adherence to antipsychotic treatment (73.0% vs 60.1%, p<0.05), and psychiatric evaluation (BPRS) (p<0.001). Results of multivariate analysis showed that the likelihood of community integration was lower with increasing age (odds ratio [OR] 0.92, 95% CI 0.89–0.94) and in the presence of minor psychiatric disorder, as compared to absence of disorder (OR=0.10, 95% CI 0.05–0.20).

DiscussionCurrently, the therapeutic goal in the management of patients with schizophrenia is to attain full recovery, including not only achieving symptomatic remission but also the highest possible level of functioning, which necessarily involves integration of subjects in the community. Adherence to treatment in schizophrenia is generally regarded as central for optimizing recovery.36 However, non-adherence remains a significant clinical problem, with rates of non-adherence approximately 50%.34 Numerous studies have provided evidence of the negative impact of non-adherence to medication on severity of disease, likelihood of relapsing episodes, and need of hospital admission for in-patient care.16,37–39 Poor insight and lack of tolerability to some antipsychotic medications are well-recognized factors associated with poor adherence.40

In a recent study of 78 patients with schizophrenia, Acosta et al.41 found superior psychopathological outcomes for patients with full adherence to their medication regimen as compared to patients with non-full adherence. The authors used strict criteria, defining 100% adherence as full-adherence and 80–99% as non-full adherence, with adherence rates evaluated using electronic monitoring (MEMS®) or the injection record in case of injectable antipsychotics.

Our study, carried out in a large sample of patients with schizophrenia and in daily practice conditions, confirms the crucial importance of adherence to antipsychotic medication not only in predicting symptomatic remission, but also in psychosocial remission and integration in the community of the schizophrenia patient.

In our study, 39.5% of patients were classified as non-adherents, with a larger percentage (59%) when adherence to non-pharmacological treatment modalities was considered. It should be noted that the rate of adherence to antipsychotic medication found in our study (60.5% of patients with adherence between 80% and 100%), should be taken with caution, since adherence was subjectively determined by the clinician based on the patient's interview at the index visit, which might have lead to an overestimation.

In relation to the primary objective of the study, symptomatic remission was registered in 28.5% of patients and was significantly associated with adherence, which seems to particularly influence positive symptoms, given that a significant relationship of adherence with blunted affect and social withdrawal was not observed (data not shown). Likewise, adherence to medication influenced significantly the probability of psychosocial remission and integration of the patient in the community. We think that psychosocial remission (achieved in 26.1% of the patients in this study) should be taken into consideration in daily clinical practice in order to assess the level of recovery of the patients. We also think a consensus on criteria for psychosocial remission should be reached in order to apply it in routine clinical practice.

At the same time, the percentage of community integration was very low (3.5%). Although this low percentage may be partly explained by the definition of this composite variable, in which presence of both symptomatic and psychosocial remission was necessary, it could be also related to the scarce vocational intervention offered to the patients. This finding raises an important question of why vocational intervention is not as present in the treatment of schizophrenia patients as it should be.

In this respect, early and sustained control of symptoms emerges an as important factor to improve the level of integration in the community, which has been increasingly recognized as an importantly element in recovery.42

On the other hand, the rate of adherence was higher for injectable antipsychotic medications (77%) (considering that in case of long-acting treatments the adherence assessment is more reliable) than for patients treated with a combination of oral and injectable antipsychotics drugs (61%) and those treated with oral antipsychotics (56%) (in which the adherence assessment has more room for error).

Also, in the 28.4% of patients whose antipsychotic treatment was changed during the index visit (in most cases starting long-acting formulation), lack of the efficacy was the first reason for change (39.6% of cases) followed by low rate of adherence (31.1%).

During the 12 months prior to the index visit, 59.1% of patients were treated with oral antipsychotics, and a relatively high percentage of patients were treated either with a combination of oral and injectable antipsychotics drugs (25%) or treated only with a long-acting injectable (15.9%). Such relatively elevated percentage of patients treated with injectable antipsychotics should be taken into account when interpreting the study results, since it might be difficult to extrapolate these results onto a different population with a lower percentage of patients with long-acting antipsychotics.

It has been previously described that early application of long-acting second-generation antipsychotic significantly reduces the risk of relapse,43,44 having the potential to address issues of all-cause discontinuation and poor compliance.45 Due to the fact that one of the advantages of long-acting drugs is the possibility to assess objectively adherence to treatment, latest generations of these long-acting formulations may be good allies to ensure compliance and, therefore, to achieve the goals of symptomatic and psychosocial remission.

Limitations of the study include the subjective assessment of adherence and the fact that reasons for non-adherence were not investigated. Because of the observational design and the fact that the study was carried out during daily clinical practice, adherence was defined based on self-reporting (by patients and/or caregivers) and the clinician's evaluation rather than using other approaches, such as pill-counting, pharmacy dispensing, missed appointments or MEMS systems. Such patient- and caregiver-reported adherence can be influenced by different factors (i.e., impact of potential cognitive deficits or recall bias) and therefore constitutes one of the study limitations. In the case of long-acting agents, withdrawal of treatment due to poor adherence, adverse events or other reasons, such as irregular administration cycles, may explain the observed non-adherence rate of 23%. Besides, both clinical impression of cognitive impairment and expressed emotion have been also evaluated in a subjective way. Finally, data were collected from stable patients who had not been recently admitted to the hospital, which may imply some selection bias and the possibility to include more adherent patients (this potential bias would have a greater impact on the group of treatment with daily oral antipsychotics). It should be also noted that this study was largely focused on the clinician's evaluations, rather than on the patient's perception of his own recovery process. In this respect, it would be interesting to use in future studies tools for patient's auto-evaluation, such as Stages of Recovery Instrument (STORI)46,47 or Recovery Styles Questionnaire (RSQ).48

On the other hand, the study has several important strong points, such as the high number of patients, the real-life character of the study and its relevance for the current clinical practice.

ConclusionsAdherence to antipsychotic medication was a significant predictor of symptomatic and psychosocial remission in outpatients with schizophrenia, which in turn influenced the level of community integration.

Ethical disclosureProtection of people and animalsThe authors state that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee and in agreement with the World Medical Association and The Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of the dataThe authors state that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the correspondence author.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed toward the inception and development of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved each version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestsDr. F. Cañas has received honoraria for lectures, advisory boards or clinical trials from Almirall, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer and Servier.

Dr. Bernardo has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, and has been on the speakers/advisory board of ABBiotics, Adamed, Almirall, AMGEN, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, Forum Pharmaceuticals, Gedeon, Hersill, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche and Servier.

Berta Herrera and Marta García Dorado are employees of Janssen-Cilag S.A. Spain.

This study was sponsored by Janssen-Cilag. Janssen-Cilag had a role in the study design, in the data analysis and in the writing of the manuscript. All investigators received economical compensation for participation in this study.

Janssen Cilag S.A. thanks Content Ed Net for writing assistance, which was funded by Janssen Cilag S.A.

Please cite this article as: Bernardo M, Cañas F, Herrera B, García Dorado M. La adherencia predice la remisión sintomática y psicosocial en esquizofrenia: estudio naturalístico de la integración de los pacientes en la comunidad. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2017;10:149–159.