This article makes a comparative analysis of the Japanese and Portuguese healthcare systems and draws conclusions as to how the Portuguese system may be reformed taking into account the Japanese experience. In a time of financial turmoil, where it is necessary to assure the maintenance of the National Health Service, it is important to learn with the best international practice: a system that has to handle, for example, with the greatest life expectancy in the world and an aging population. The results of a survey carried out on 400 people (200 Japanese and 200 Portuguese) on the degree of satisfaction with the health care system, costs, patient–doctor relationship and alternative medicine use are analyzed as well.

MethodsComparative analysis, surveys and interviews.

ResultsThe Japanese population has a higher grade of satisfaction of their healthcare system than the Portuguese.

ConclusionsThe Portuguese healthcare system may use some of the methods of the Japanese healthcare system in order to achieve better outcomes, be more efficient and therefore to better serve the general public.

Neste estudo procede-se a uma comparação entre os sistemas de saúde japonês e português, no sentido de perceber em que medida o sistema português pode aprender com o sistema japonês. Nesta altura de crise financeira e económica, em que é necessário garantir a sustentabilidade do Sistema Nacional de Saúde, importa aprender com as boas práticas internacionais de um sistema que tem de lidar, por exemplo, com a maior esperança média de vida do mundo e uma população também cada vez mais envelhecida. Também são analisados os resultados de um questionário feito a 400 pessoas (200 de nacionalidade japonesa e 200 de nacionalidade portuguesa) sobre o grau de satisfação com o sistema de saúde, os custos, a relação médico-doente e o uso de medicinas alternativas.

MétodosAnálise comparativa, questionários e entrevistas.

ResultadosMaior grau de satisfação da população japonesa comparativamente com a população portuguesa.

ConclusõesO sistema de saúde português pode utilizar alguns métodos que o sistema de saúde japonês tem utilizado para atingir melhores resultados, ser mais eficiente e, assim, ser capaz de melhor servir a população.

A person's health is a major factor in determining his or her quality of life. It is always on his or her mind, as is the concern of suddenly becoming ill, which may come about due to unforeseen circumstances or may be the result of something that has always been there, just lingering under the surface.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined “health” as “a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.1 Though the right to health has been declared a basic human right across the globe, only citizens in developed countries have come to expect the provision of healthcare services as a certainty. That certainty does not exist across the underdeveloped world.

Those immediately responsible for ensuring patients have access to quality healthcare are the professionals working in the field, such as doctors, nurses and technicians. They are not alone in this task, however, as administrators, managers and governors are also an integral part of the system. Ultimately, developed countries have set up public healthcare systems, whether through regulation of private enterprise, in an attempt to maximize coverage, or through direct provision of healthcare services by a public entity, whose purpose it is to deliver quality healthcare to its citizens.

Due to the ongoing economic and financial crisis in Portugal, the financial sustainability of the National Health Service has been thrown into question and finding a way to solve this issue has become even more urgent than before. The National Health Service, as well as the whole Healthcare sector, needs to be reformed to become more efficient, delivering quality universal healthcare for all at a financially sustainable cost.

In the global world we live in today, it is important to focus not only on one's own country, but to widen one's horizons and try to understand other countries as well. Learning and exchanging ideas with others have always been a trigger for change in History, in both bad and good times.

Countries have different cultures, and culture plays a very important role in determining people's behavior, which has an impact on all aspects of society, from demography to health. Japan has been “westernizing” its culture since the mid-XIX century, a process that has only been strengthened by American influence in the post-World War II (WWII) period. That said, old habits die hard, and many traditional aspects of Japanese culture remain strong even today.

Portugal has always been a part of the Western world and, in particular, Latin and Mediterranean cultures, with important Catholic influences. Urban areas, in particular areas near the ocean, contrast sharply with rural areas deeper into the Iberian Peninsula in terms of, for example, eating habits. Many traditions lost in urban areas still live on in the countryside.

This article will compare the health care systems of these two countries, Japan and Portugal, in an attempt to learn what sets them apart and brings them together, as a means of contributing to the current debate on how to reform the Portuguese healthcare system.

Healthcare in JapanThe current Japanese healthcare system, the “Kaihoken”, has been in place for the last 50 years. It has proven quite effective at providing universal healthcare coverage, being its driving force “health insurance for all”.2 Implemented in 1961 after WWII, the kaihoken, together with benefits having become more egalitarian, keeps health expenditures relatively low (8.5% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)). Furthermore, it managed that Japan's healthcare system nowadays ranks 20th in terms of expenditure among the countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2008. The percentage of the population aged 65 years or older has increased nearly four-fold (it raised from 6% to 23%) over the past 50 years.

It all started with the inauguration of Emperor Meiji in 1868 when the Japanese Government decided to strive on a policy to promptly westernize Japanese society. Regarding healthcare, the government successfully changed the basis of medical practice from Chinese to western medicine.3 Japan's universal medical care insurance system adopted the German social health insurance model in which both employers and employees manage the insurance plans.4 Citizens have to pay monthly insurance premiums under the social insurance system. It includes two types of public insurance schemes: National Health Insurance and Employee's Health Insurance. It is compulsory to be insured under one of those schemes and, taking into account their age and their profession, people are included in either type of insurance.5 The system is funded through insurance premiums, public funds (tax), and co-payment. When compared to private insurances its advantage is that premiums are levied taking into account the ability to pay, and not on the risk of illness. The national government as the largest of the group of health insurance carriers is most likely the most distinctive element of Japan's health insurance system nowadays.

Employee's Health Insurance is formed by the Health Insurance Society, with 32.58 million subscribers6 and the Government-Managed Health Insurance (37.58 million subscribers).6 Employees of large companies are covered by the Health Insurance Society, while the Government-Managed Health Insurance is for employees of small to medium size companies (defined as companies that employ more than five but fewer than 300 people), for national or for local government and those working for private schools. Premiums are calculated based on the insured person's monthly salary (not including bonuses, which are subject to a separate tax), and are equally divided between the employee and employer. They are deducted from the employee's monthly paycheck (the deduction is around 4%). Those insured under this scheme only have to pay 20% for their hospital costs and 30% for co-insurance for outpatient care.

National Health Insurance has 45.45 million subscribers and covers everyone who is not employed (students, expectant mothers, retirees, etc.), self-employed people and those working in agriculture, forestry or fisheries. Premiums are calculated based on the insured person's salary, property, and number of dependents (again, the deduction is about 4%).7

However, not everything is covered by the National Health Insurance: treatment unrelated to illness (such as health examinations, normal pregnancy and childbirth, preventive vaccinations, orthodontic work, induced abortion or contraception for financial reasons or cosmetic surgery), treatment received outside of Japan or failure to follow treatment suggested by the doctor are excluded in this type of insurance. Injury due to an illegal act, fighting or drunkenness and self-inflicted illness or injuries are also excluded. In case there's an injury during work, it is either covered by the employer or a compensation for the worker.

There's also a third type of medical insurance, the Health Insurance for the Elderly that was established in 2000. This type of Insurance covers the elderly and the disabled and provides additional benefits to individuals who are 65 or older, or between the ages 40 and 64 but suffer from disabilities. It is funded by contributions from the two main schemes and members have to pay 20% of medical costs.

The program's purpose is to give people the ability of living in the community and the house where they have grown used to living, to choose services and to make the most their own abilities, in an effort to allow people to maintain their dignity and independence. The program therefore offers home care (visiting nurse), respite care, or institutional care based on the needs of the elderly individual. More than 50% of people wish to receive care at home require nursing care.8

Long-term care is provided exclusively by trained, licensed and supervised caretakers, as it is believed that only then they are able to provide the appropriate quality of care. They may choose the services and their providers, taking into account the recipients’ level of physical and mental impairment. The latter are licensed and supervised by local governments, with consumer choice serving as the most important factor for quality control.9

According to “people's opinions concerning the long-term care insurance system,” which were collected by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in 2010, more than 60% of respondents said that they valued their long-term care insurance system. It has also been demonstrated that the State is able to save more money thanks to this program: people tend to be healthier as they are encouraged to live a meaningful and healthy life. Care prevention is also promoted in order to minimize the use of care services.

Japan is the country with the longest life expectancy in the world (average life expectancy is 83, and healthy life expectancy is 76), so this program cannot be considered to be a small concern. There has been an increase in medical expenditure due to a rapidly aging population and young people have to support that expenditure.10 Need for the program has grown to such an extent that its financing needs have outgrown its budget, though the system has been praised by WHO. The budget of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in fiscal year 2011 is about 29 trillion yen.

In order to obtain medical treatment, people have to show their insurance card on site. People are free to choose any medical institution of their preference to receive treatment, be it public or private, under Japan's free access system. There is no difference between public and private hospitals when it comes to payment, as prices for every medical procedure are set by the State. Both prices and the level of reimbursement of medical fees are revised every two years. This fee schedule that dictates the price and conditions for all plans is one of the factors for a successful containment of costs in Japan.11

Each of the 47 first-order subnational jurisdictions (prefecture) has its own oncological hospital, and each oncological hospital is obliged to have a palliative care unit. There are not many palliative care institutions outside hospitals in Japan.

Local government organizes prevention and screening campaigns on a regular basis, though there is also some national government involvement. Due to the high incidence of cancer and lifestyle-related diseases, national government promotes research on matters related to increasing people's healthy life expectancy, focusing on the prevention and treatment of lifestyle-related diseases. One of the Government's plans is to increase cancer screening by 50%, expanding the coverage of a free coupon project encompassing breast and cervical cancer to also encompass colon cancer. Back in 2008, the national campaign of the Health Service Bureau was based on three pillars: “proper exercise”, “appropriate dietary habits” and “stop smoking”. An increase of tax on cigarettes is also being considered as a future measure and discussions are being held on reforming the national vaccination system (in 2010 an urgent vaccination program was already introduced for cervical cancer, Haemophilus influenzae (HiB) and Pneumococcus).

Other campaigns include blood donation, measures against drug use and ensuring the efficacy and safety of drugs and medical devices. Regarding the latter, research on genetics and nanotechnology is supported by the state.

Regarding screening and prevention, the government promotes and demands an annual check-up for every citizen. These might be carried out at clinics, hospitals or, when it comes to children, at schools. Medical professionals in charge of these check-ups are mostly General Practitioners, but those can also be done by specialists (e.g. an Otolaryngologist may be asked to check children's ears, noses and throats at school) too. Pregnant women have access to prenatal care at obstetrics clinics, which they have to visit themselves.

It is believed that the development of technologies in the health sector (medical and nursing care) will be one of the main pillars to support Japan's future economic growth. Japan's information technology is at top international level in terms of infrastructure development, together with the rate of users. Japan wants to be an information hub and to contribute with technology and know-how to the global progress of medical sciences.

Japan's electronic database has been in place for about 10 years and 70% of the hospitals in Japan already have an electronic database. The program each hospital uses might be different, but they are all connected. When it comes to primary care clinics, there has to be a contract between the hospital and the latter so that the database can be mutually accessed. There is an attempt to establish a “clinical pass”, so as to include every citizen in one single database.

Regarding hospital evaluation, there is a Medical Health Quality Agency responsible for this task. A hospital's quality is checked three to five years, though this is not a requirement. The hospital itself will generally request the Agency to evaluate it. In a medical system where the market offers the same prices everywhere, it is in the hospital's interest to shine in order to attract further patients. Therefore, in order to improve the hospital's rating, they ask for a hospital evaluation. This evaluation has then to be paid by the hospital.

Concerning medical work as such, Japan is living through a shortage of available doctors, especially when it comes to rural areas and the specialties of obstetrics/gynecology, pediatrics and emergency physicians. As a short-term measure, the government decided to increase the income of those doctors who choose to receive resident training in a rural area. In order to fight this deficit, a higher number of students are already being allowed into medical school. Regional medical care support centers are being considered as a means of coordinating work done in prefectures and to ensure each region has a sufficient number of doctors.

Based on the principle of receiving necessary medical care when needed, the government is giving financial support for centers that accept severely suffering ill patients around the clock. A nighttime telephone counseling system for pediatric patients has also been implemented.

Medicines are prescribed on active ingredient in Japan. At a pharmacy, a patient is able to choose whichever prescribed drug he or she prefers based on the active principle of the drug. Most of the time, doctors choose not to allow generic drugs to be given out to the patient in order to assure therapeutic effect. The Ministry of Health is asking doctors to prescribe generic drugs over trademarked ones, but at the moment only 20–30% prescriptions prefer generic drugs over trademark ones. Unidose prescription is not yet available in Japan.

There's no fee for the use of an ambulance. There is also no exclusion for the use of an ambulance when it comes to hospitalized patients. That is the reason for local government to promote campaigns of “not using the ambulance”.

Medical institutions in JapanThere are two types of medical institutions in Japan: clinics and hospitals. Hospitals have twenty beds or more. Clinics, on the other hand, may have no beds or up to 19 beds. While hospitals must have substantial facilities and be able to provide adequate medical care, there is no strict regulation when it comes to clinics.

There are five types of hospitals in Japan:

- •

General hospitals;

- •

Special functioning hospitals (providing advanced medical care);

- •

Regional medical care support hospitals (support family doctors and family dentists);

- •

Psychiatric hospitals (with psychiatric wards only);

- •

Tuberculosis hospitals (with tuberculosis wards only).

All medical institutions in Japan are obliged to report in all of their medical mistakes or cases of negligence in order to make it easier to avoid them in the future.

Healthcare in PortugalAccording to the Portuguese constitution, everyone has a right to health. The Portuguese Health Service's goal is to ensure everyone has access to adequate medical care, free at the point of use, irrespective of socio-economic condition. To achieve this goal, the Government set up a National Health Service (NHS) in 1979,12 which provides universal health care coverage. The NHS tends to be free at the point of use, but there are copayments (sometimes running up to 40% or more) for diagnostic tests, hospital admissions, specialist visits and prescription drugs. The NHS is complemented by private health care provision, and the Portuguese health system therefore includes both a public and a private component.

Every citizen has a National Health Service number which gives him or her access to public healthcare services. Alongside the NHS, there are both special health insurance schemes (health subsystems) for various professions (e.g. public sector employees with the ADSE, the military via the ADM) and voluntary private health insurance. About 25% of the population is covered by health subsystems, 10% by private insurance and 7% for mutual funds. The third sector also has institutions that provide medical care, many of them with their roots in the Catholic Church (“Misericórdias”). They not only care for those in the most need, providing acute care, but also accompany the chronic patients.13

The Health Ministry is in charge of both developing health policy and running the NHS. The NHS includes five regional health administrations, which are charged with implementing national health policy objectives, developing guidelines and protocols and supervising health care delivery. Though it has been stated policy to shift power to regional health authorities, in practice, regional health authorities’ autonomy is restricted to primary care.14 The Ministry of Health also organizes public awareness campaigns, such as blood donation, using the media.

The NHS is funded through general taxation. Health care spending accounts for 13% of public revenue, and the NHS budget tends to have a large deficit. Health subsystems are paid for through a combination of employee and employer contributions. Direct payments by the patient and health insurance premium make up the remainder of health funding in Portugal.

Doctors were recently provided with clinical orientation norms by the Directorate General of Health, to help them in their practice and standardize procedures. Screening campaigns are, for example, included in these norms.15

Primary and secondary care doctors working in Portugal are either employed by the State or opt to work for private practice. Doctors may also opt for private practice, and to work for the State on a contractual basis.

In the Portuguese NHS, family doctors act as gatekeepers, and a patient may only consult a specialist with the consent of a family doctor. Patients must choose doctors from a list, and, unless there is mutual agreement, they may only switch doctors through written application.

Using the NHS, citizens may go to their family doctor whenever they make or have an appointment, be it for prevention, because of their chronic condition or an acute disease. Family doctors accompany children and pregnant women at their local health center and they may always send the patient to the hospital whenever it is needed. These local health centers are not open at night or weekends; therefore people have to go to the hospital in case they need medical treatment. Furthermore, patients can only go to a health center, if they are enrolled in it or they live in the surrounding area. It should also be noted that not every person has a family doctor, which hinders access to health care. Though there are doctors who provide care to these patients, they are not at all sufficient.

Private insurance covers hospital stays and specialist care. There is no guaranteed renewability, however. This means premiums are significantly raised or clients tend to be dropped, in case of very high claim amounts.

The NHS is lacking when it comes to technology. X-rays and computed tomography can be relatively easily performed; however, family doctors are not allowed to request expensive complementary means of diagnosis, such as magnetic resonance imaging. Those can only be performed at a hospital and requested by hospital medical staff, or through a private medical practice, where they have the necessary technology at hand.

At the moment, communication between primary and secondary care in the NHS is also very lacking, as there is not an interface that connects both specialists. Even though primary and secondary care providers are equipped with an electronic database, in some cases patients still have to serve as intermediaries, by carrying letters containing their medical information between doctors. The situation is worsened due to the co-existence of the public and private services. However efforts are being made to tackle this flaw.

There has been an increase in the prescription of generics in Portugal, which has caused a boom in the availability of generics by different laboratories, mainly respecting the most frequently prescribed drugs. Unidose prescription is not yet possible, as well.

What's more, waiting lists in the NHS are very long in Portugal. The European Observatory on Health Systems claims that Portugal is rationalizing its health care services, causing many to go to Spain for treatment or head for the emergency department. In fact, at least 25% of hospital emergency room patients do not need immediate treatment. This might be explained by the shortage of family doctors in Portugal, mainly in the inner regions of the country, causing many people to not have access to primary care.

Though, in theory, all benefits are covered, in practice, certain benefits such as dental care or rehabilitation are limited in the NHS. Dental care only covers children up to the age of 15, pregnant women and the elderly who qualify for supplementary benefit (“Complemento Solidário para Idosos”).16 Otherwise, people have to make an appointment with a dentist in private practice.

Portugal has a public medical emergency service that operates 24hours a day, together with a telephone service that answers people's medical questions and references them to the correct medical institution, if necessary. Free ambulance use was recently restricted to very strict rules, due to the financial crisis.

Medical institutions in PortugalThe Portuguese National Health Service includes the following medical institutions:

- •

Grouping of health centers;

- •

Hospitals;

- •

Local health units.

Continued care is provided through a network of public and private health care providers and has as its goal to provide more autonomy to those in need. Local public palliative care units look after palliative patients, though admittance is very difficult.

MethodsThis study consists of a transversal analysis of two healthcare systems taking into account their structure and results. In order to better understand how each healthcare system is perceived by the country's population, a small survey was handed out to 400 people (200 people in Japan and another 200 in Portugal). This survey was anonymous and all the individuals were chosen at random. When processing the data, surveys were divided into three groups (0–29 years; 30–59 years; over 60 years) to investigate whether a pattern of response by age existed or not.

The surveys are a form of preliminary data collection from a convenience sample. Though their interpretation must be limited and careful, they still provide information that is of interest for the purposes of this paper.

The reason why these two healthcare systems were chosen was to better understand how two very different countries performed in healthcare. At a time when population is aging at an alarming speed in the developed world, which is coupled with a high decrease in birth rates, Japan is the country with the highest life expectancy in the world. Portugal is currently facing hardship of its own when it comes down to handling geriatric patients, so Japan's healthcare system is a good one.

AnalysisIf we look into the data published by WHO in 2010 on health expenditure ratios, the total expenditure on health as a percentage of GDP in 2007 was higher in Portugal (10%) than in Japan (8%). This means that Japan spends a lower percentage of available resources on health care than Portugal. It is important to take this into consideration when we consider the figures below.

In Japan, 81.3% of total expenditure on health was public expenditure, while in Portugal, that figure was 70.6%. This represented 17.9% of the Government's budget in Japan, and 15.4% in Portugal. As noted above, Japan has several public health insurance schemes, which explains the fact that 78.7% of general government expenditure on health goes through social security, while that figure is only 1.2% in Portugal.

In terms of private spending on health care, though private pre-paid plans increased from 1.7% to 13.7% of private expenditure on health, out-of-pocket expenditure remains prevalent in Japan. In Portugal, the figure remained relatively constant – private pre-paid plans represented 11.1% of private health care expenditure in 2000 and 13.8% in 2007. The relative absence of pre-paid plans may be explained the fact that, given public systems cover most healthcare issues, people will not be interested in selecting and paying for pre-paid plans, as paying out-of-pocket will be enough to cover their needs.

Per capita total expenditure on health was 2121€ in Japan and 1625€ in Portugal (at average exchange rate). The figures were 2180€ and 748€ in 2000 (also at average exchange rate), which shows a tremendous increase in Portugal, an increase that is also observable when one considers per capita expenditure as expressed in terms of purchasing power parity (figure increases from 1163€ to 1761€). In Japan, while there was a decrease if one considered average exchange rate figures, there is an increase if one considers Purchase Power Parity (PPP) (from 1516€ to 2078€).

When one considers per capita governmental expenditure on health, one observes a very slight decrease in Japan, from 1772€ to 1725€ at average exchange rate, while there is an increase if you consider PPP, from 1232€ to 1691€. In Portugal, per capita government expenditure increased from 542€ to 1148€ at average exchange rates, while the increase in terms of PPP was from 844€ to 1243€.

MortalityAverage life expectancy for both sexes diverged by four years in 2008 (83 years in Japan and 79 years in Portugal). Healthy life expectancy at birth was 76 years in Japan and 71 years in Portugal, respectively, also in 2007. Neonatal, infant mortality rate and under-five mortality rate were in 2008 very similar in both countries as well. Among children younger than five, the most frequent cause of death in both countries is congenital abnormalities. Other causes of death include other diseases and injuries in Japan, while in Portugal prematurity, other diseases and birth asphyxia are other prevalent causes of death.

The adult mortality rate is the factor that differs the most when comparing both countries, as it is much higher in Portugal than in Japan. The probability of dying aged between 15 and 60 years per 1000 population for both sexes figures is 65/1000 in Japan and 90/1000 in Portugal (men: 87/1000 in Japan and 128/1000 in Portugal; women: 43/1000 in Japan and 52/1000 in Portugal). The adult mortality rate has been decreasing in Portugal since 1990, but it still maintains at a considerably higher level than in Japan, especially among men.

MorbidityIf we look at the “selected infectious diseases” data from 2008, an immense gap can be observed when comparing both countries. The number of reported cases of measles, mumps, pertussis, rubella, tetanus and tuberculosis in Japan is much higher than the numbers gathered in Portugal. Immunization coverage among one-year-olds is 97% for measles and Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) in both countries. However, there are no data about Japan regarding immunization for Hepatitis B (HepB3) and Hib3. In Portugal the latter two also have coverage rate of 97%.

Taking tuberculosis into account, the two countries have the exact same rate of smear-positive tuberculosis case-detection (87), however the smear-positive tuberculosis treatment-success rate in Portugal was, in 2007, 87% and, in Japan, 46%. Prevalence and incidence of tuberculosis per 100,000 people are slightly higher in Portugal; nevertheless the number of reported cases is eight times higher in Japan.

If we take other risk factors into account, obesity and alcohol consumption are much more prevalent in Portugal than in Japan.

In Japan, around 2.9% of adult males over 15 are obese, while 3.3% or adult females over 15 are obese. These numbers in Portugal are 15% for males and 13.4% for females.

Alcohol consumption among adults over 15 is also important to look into. In Japan, one person will consume 8l of pure alcohol per year, on average, while that figure is 12.2l per person per year in Portugal.

When it comes to smoking, Japanese men tend to smoke more than Portuguese men (42.4% versus 33.7%). On the other hand, it seems there is a higher percentage of women smoking in Portugal than in Japan (15.5% versus 12.6%).

Demography and socioeconomic statisticsJapanJapan has a total population of 127,293,000. The median age is 44. The percentage of those under 15 is 13%, while the ones aged over 60 is 29% of the population. The total fertility rate per woman is 1.3 and the adolescent fertility rate (per 1000 girls aged from 15 to 19 years) is 5. The annual GDP growth rate, meanwhile, is 0.1%.

66% of the population lives in an urban area and the gross national income per capita 27161€.

There are 270,371 physicians practicing in Japan resulting in a density of 21 physicians per 10,000 people. There are 1,210,633 nurses (95 per 10,000 people), 95,197 dentists (7 per 10,000 people) and 241,369 pharmaceutical personnel (19 per 10,000 people). Finally, there are 139 hospital beds per 10,000 people.

PortugalPortugal's population is 10,677,000 people and the median age of 40 years. Those under 15 years make up 15% of the population and the ones aged over 60 years 23%. The total fertility rate per woman is 1.4 with an adolescent fertility rate of 17 per 1000 girls aged from 15 to 19 years.

The annual growth rate is 0.5%, where 59% of the population lives in an urban area and the gross national income per capita 17028€.

There are 36,138 physicians working in Portugal resulting in a density of 34 physicians per 10,000 people. There are 50,955 nurses (48 per 10,000 people), 6149 dentists (6 per 10,000 people) and 10,320 pharmaceutical personnel (10 per 10,000 people). Finally, there are 35 hospital beds per 10,000 people.17

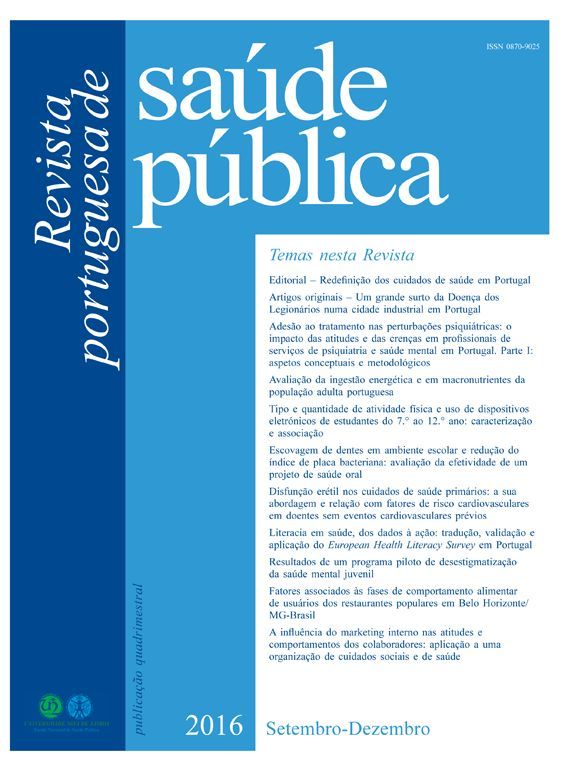

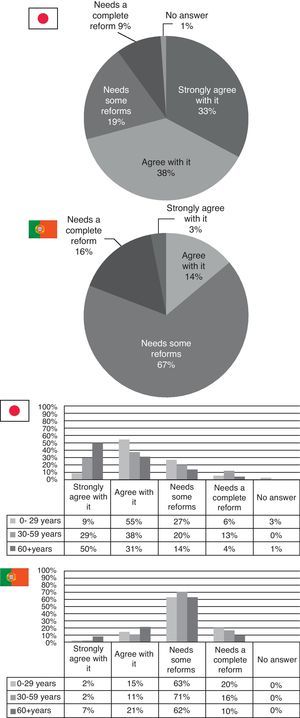

Survey resultsWhen asked about their country's healthcare system, it seems that the Japanese view their system in a better light than the Portuguese. 71% of Japanese respondents either agree or strongly agree with their current healthcare system (especially those aged 0–29 and those over 60), while 67% of the Portuguese, within all ages, answered that the Portuguese healthcare system was in need of some reforms (Fig. 1).

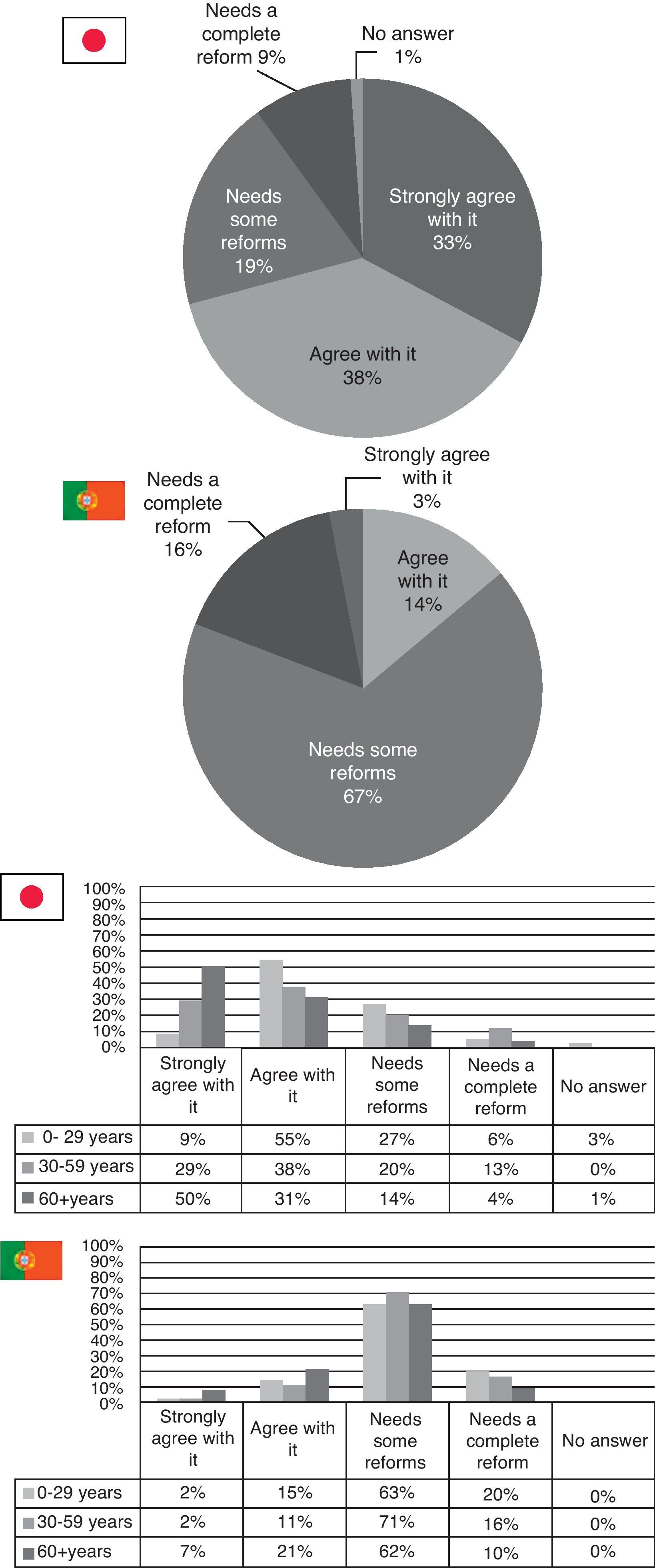

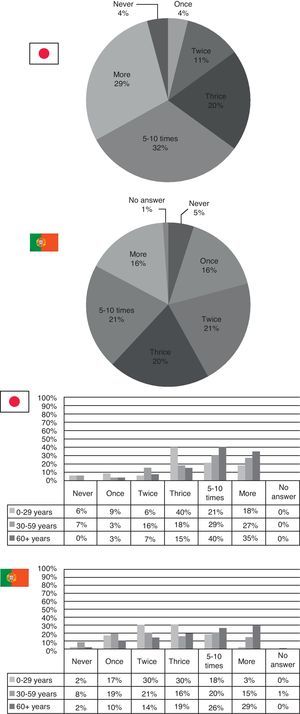

As for how frequently someone visited a doctor in one year, Japanese respondents tend to consume more healthcare services than Portuguese do. In Japan, 32% visit a doctor five to ten times a year and 29% even more than ten times a year. In Portugal, 41% visit a doctor twice or thrice a year (the highest percentage being those aged 0–29 years), 21% five to ten times a year and only 16% go more than ten times a year (mostly those over 60) – see Fig. 2.

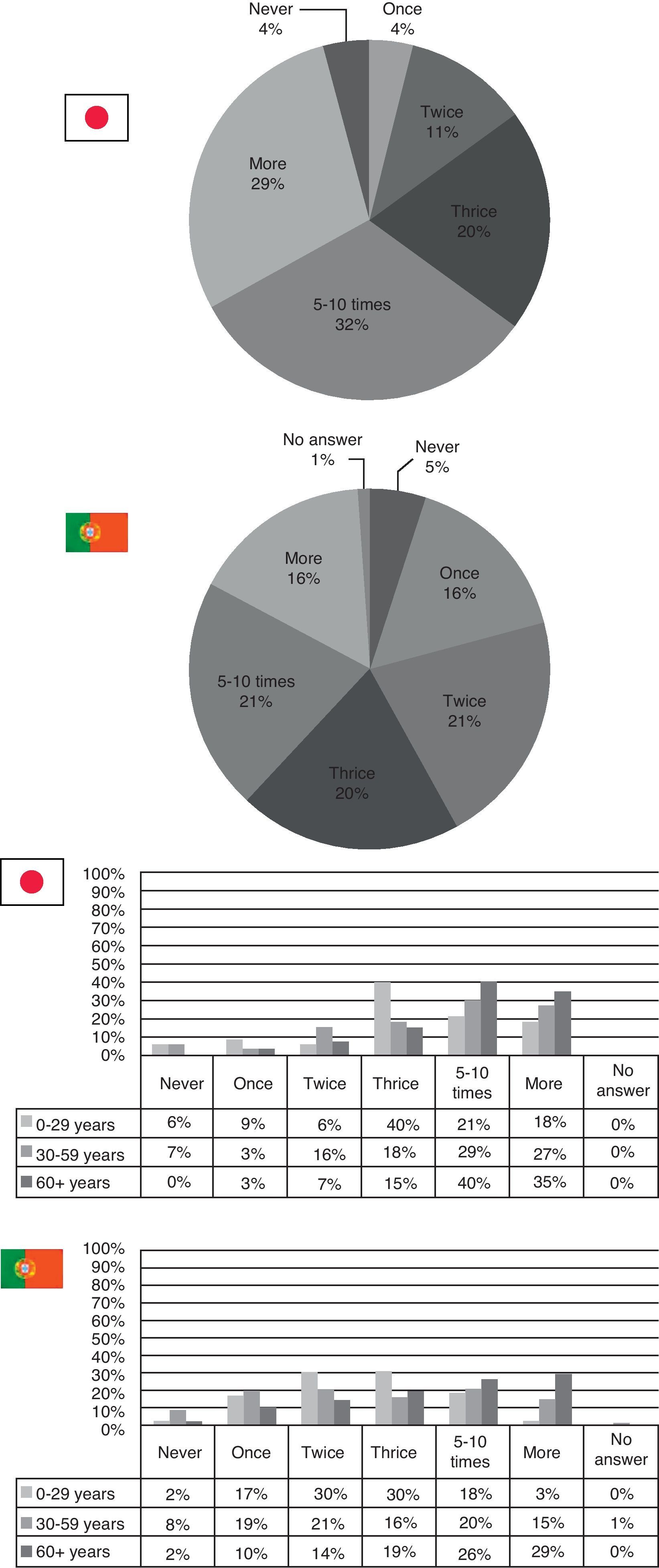

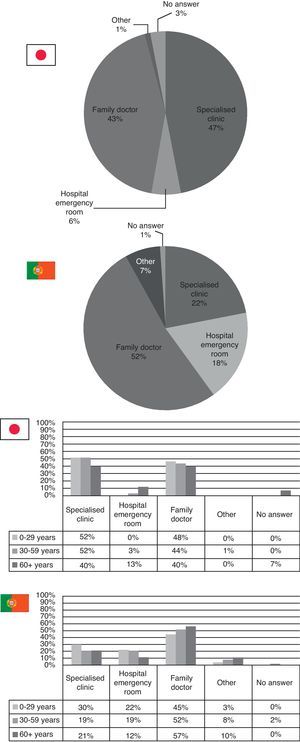

When feeling sick, Japanese results show that about half of the respondents choose to either go to a specialized clinic (47%) or visit their family doctor (43%). In Portugal, 52% go to their family doctor and the other two big options are either visiting a specialist (22%) or the hospital emergency room (18%). Those who directly go to their family doctor are mostly those over 60 years (Fig. 3).

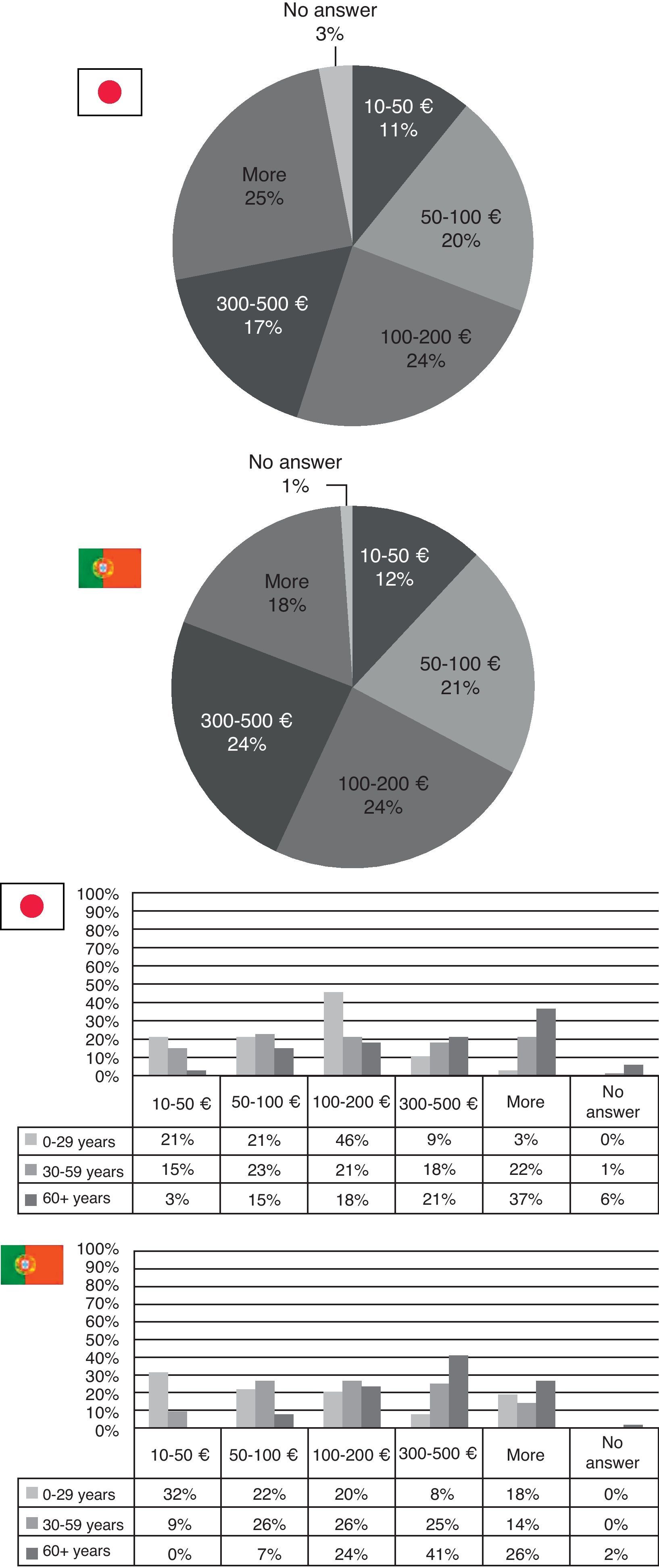

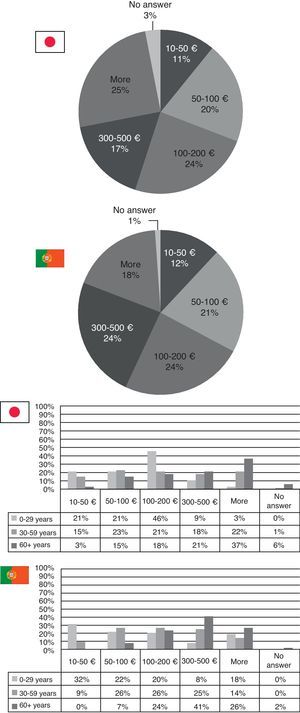

Considering how much patients spend on medical care per year in both countries, more than half of the population states that they spend less than 200€ a year in medical care. In Japan, 25% consider they spend more than 500€ a year while in Portugal it's 18% who say so. In both countries it can be seen that the more elderly population is the one who spends most money in medical care, however these numbers are higher for Portugal than for Japan (Fig. 4).

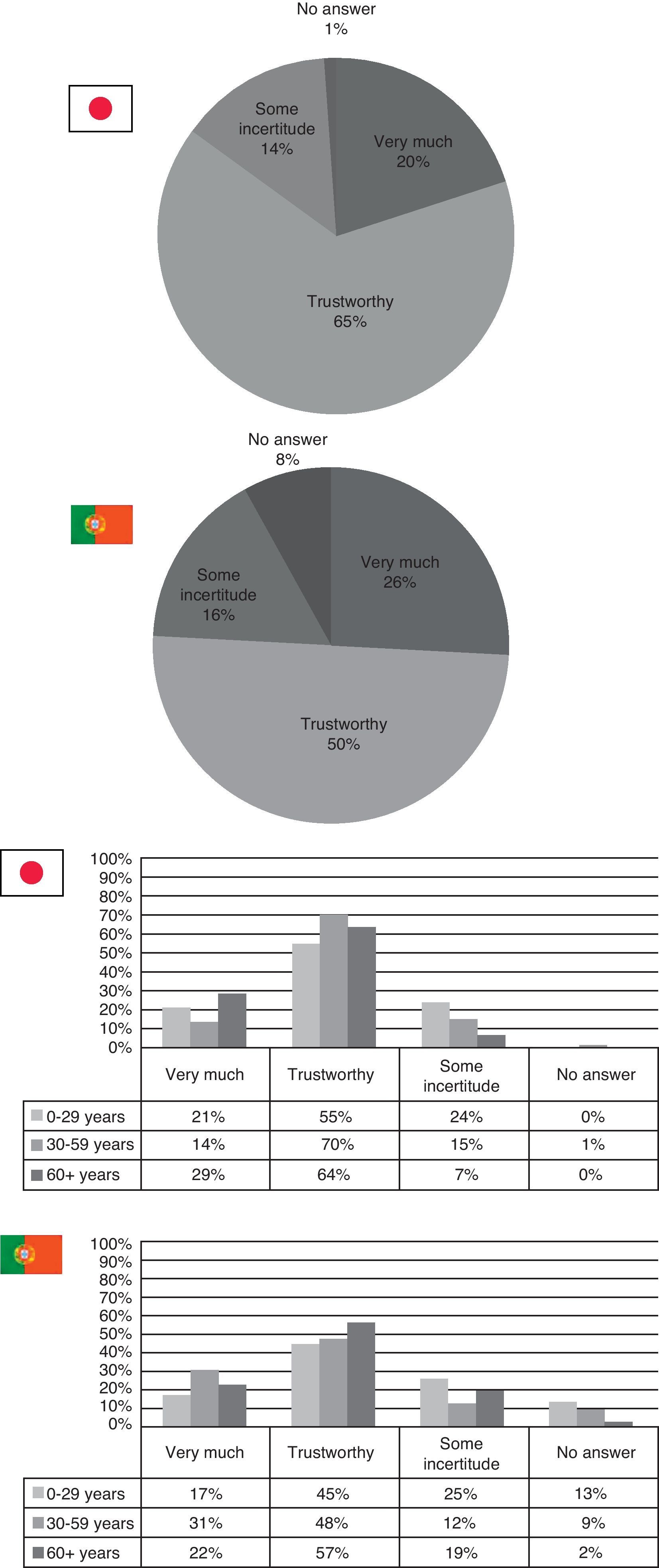

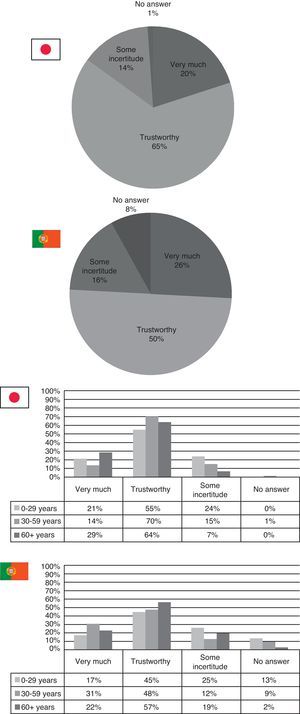

Asking people's opinions on their physician, it seems that people in both countries trust their physicians. In Portugal there is a slightly higher amount of those who have very much trust in their physicians especially in those aged 30–59 years. However, when it comes to feeling uncertain about their family doctor among those over 60, there are more people feeling uncertain in Portugal (19%) than in Japan (7%) – Fig. 5.

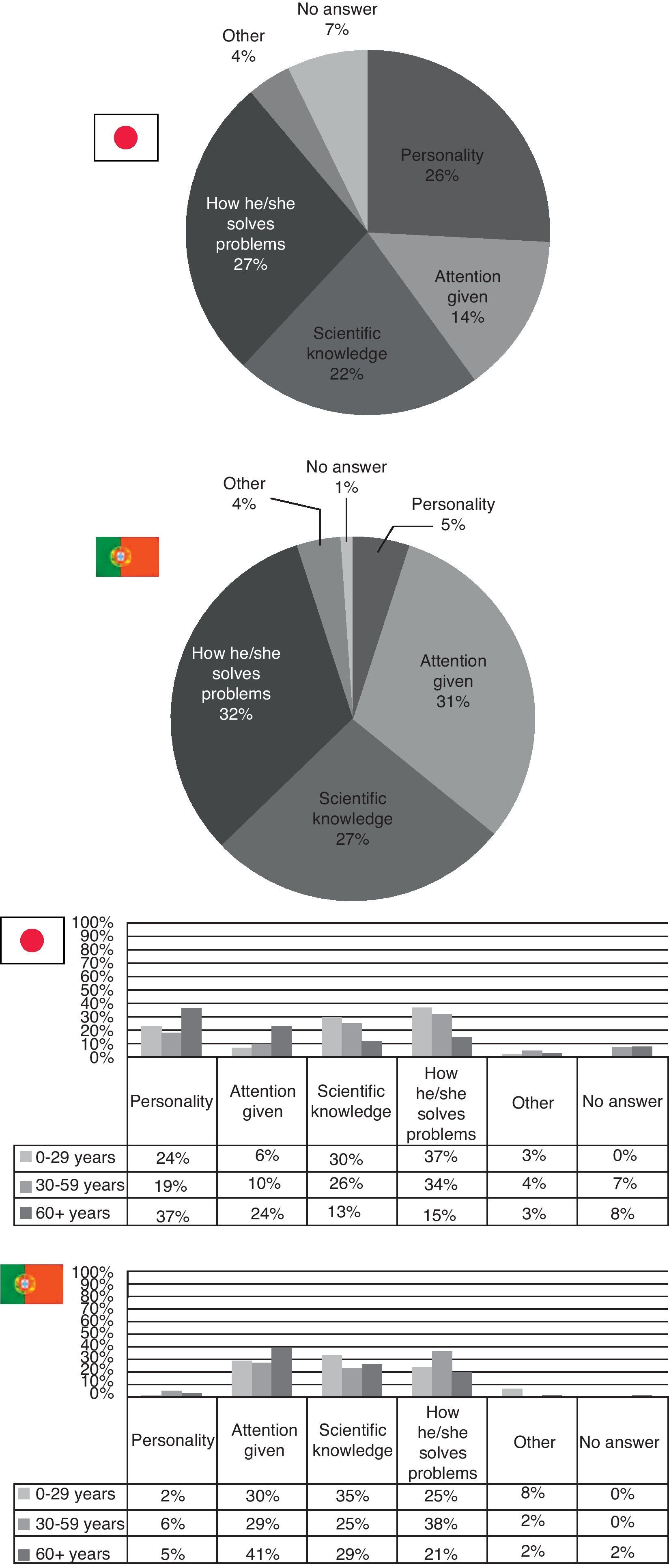

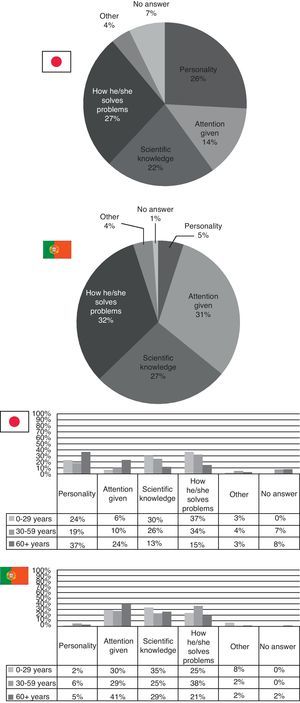

As for the traits, the patients value most in a physician, scientific knowledge and the capacity to solve problems were the two most popular traits in Japan in those aged up to 59 years. People over 60 mostly valued the personality of their doctor. In Portugal, both the scientific knowledge and the capacity to solve problems had a high percentage (with the latter being mostly apprehended by people aged between 30 and 59 years), however, people of all ages valued the attention given by the doctor much more strongly than in Japan (Fig. 6).

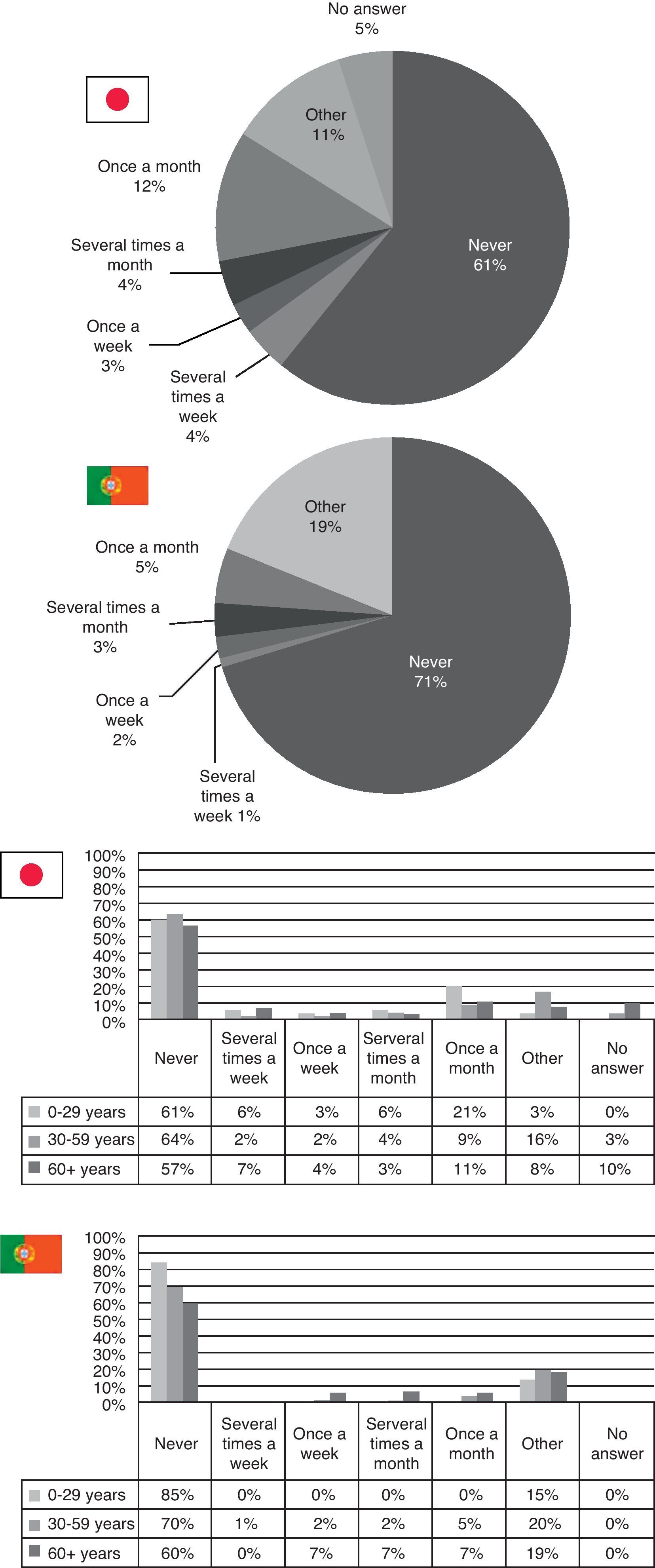

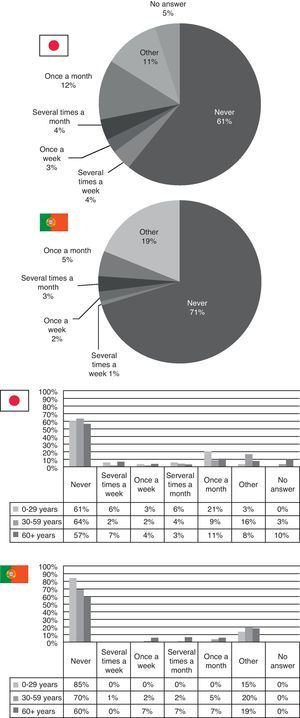

When it comes to alternative medicine including acupuncture, massage, homeopathy, etc. neither country's patients opt for it a lot. In Japan, 61% say they never recur to alternative medicine and in Portugal this percentage rises to 71%. Only 12% say they use it once a month in Japan (Fig. 7).

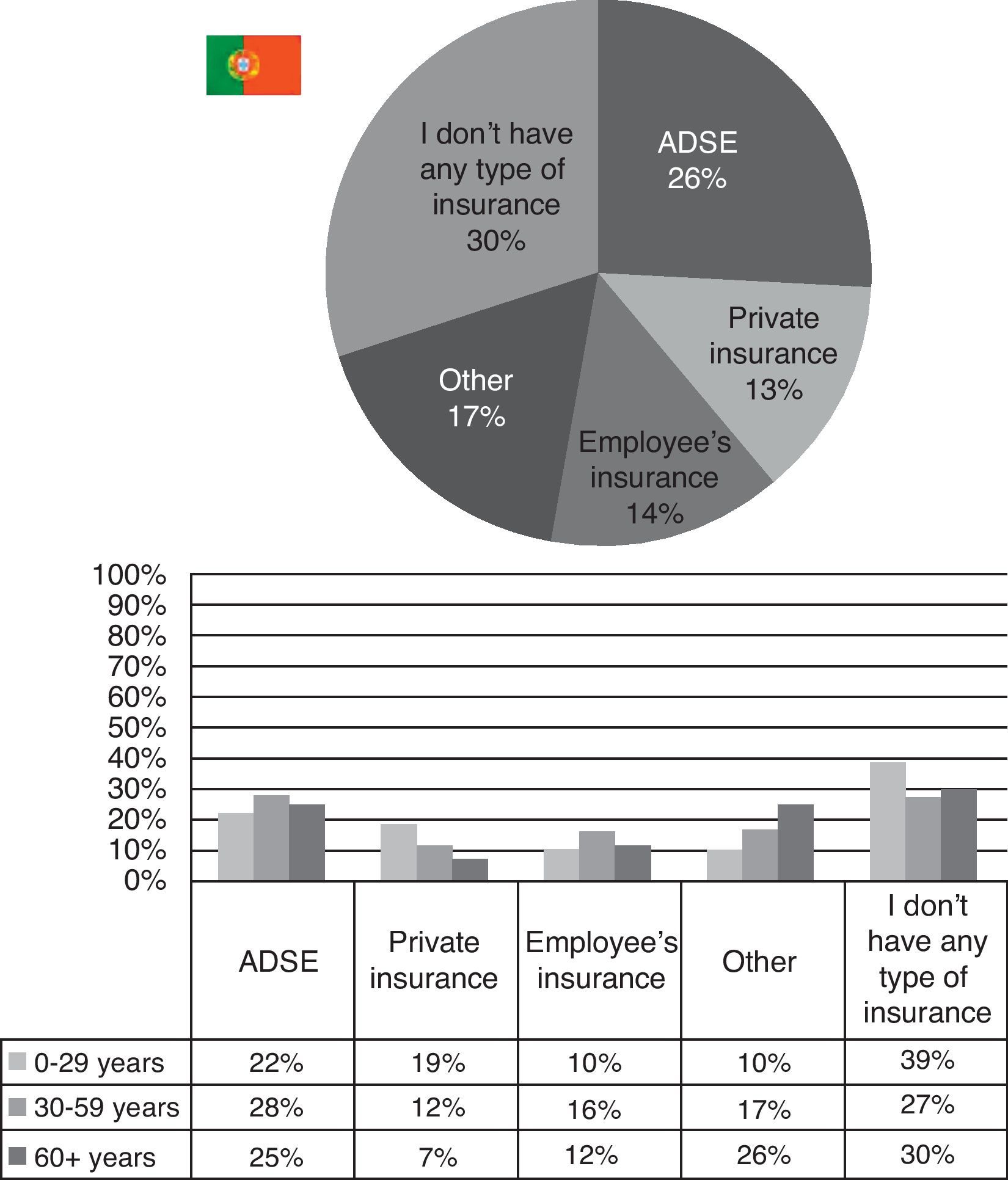

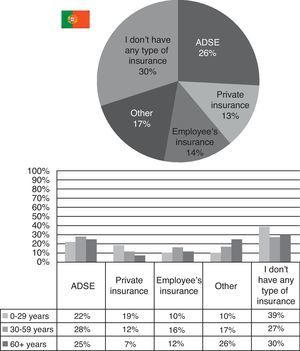

The last question of the survey was only asked in Portugal, as it could not be applied in Japan. It was to better understand how many types of insurances schemes Portuguese people use, besides of the basic public program. 26% have ADSE and 14% employee's insurance (both of them more common for those between 30 and 59 years), 13% have private insurance (being it more frequent in those up to 29 years) and 17% picked “other”. The greatest majority (30%) affirmed they did not have any type of insurance besides the social security program (Fig. 8).

DiscussionWhen comparing the two countries, there is quite a difference between both systems. Although both of them are based on a social insurance plan, where everyone is allowed medical care free of charge at the point of use, Japan spends a lower percentage of GDP to obtain results that tend to be either better than, or similar to, those in Portugal.

We must take into account the effect culture has in both. Culture influences behavior and habits, and these, for their part, have an effect on health. Japan is a great example to illustrate how a population with a high level of education greatly influences health outcomes.

As was already mentioned, Japan was devastated after WWII. The country was at a level that can be compared to contemporary India (per person domestic product was roughly international 2622€ in 1950). Life expectancy was not much better: in 1947 male life expectancy was 50 and female 54. However, thanks to rapid economic growth during the late 1950s the country managed to catch up with other developed nations and, since 1986, it has ranked first regarding female life expectancy at birth.

Before WWII, the government decided it was critical to establish two key public services: free compulsory primary education and a social insurance system.18 There were still some disparities, but the universal health coverage system in 1961 provided equal opportunities for health promotion. Furthermore, regional and socio-economical differences were also reduced considerably along the years, thanks to the homogenous and egalitarian society that was created. This egalitarian society, a strong government leading public health program (e.g. tuberculosis, promotion of salt reduction and the primary care management of high blood pressure with anti-hypertensives), together with the high levels of education that were attained and Japan's intrinsic culture of hygiene, were probably the factors that led to this success.19

In Japan, there is a tradition of preserving nature and finding the balance between human intervention and nature. Noise is frowned upon, and Japanese try to preserve stillness as much as possible. When it comes to hygiene, Japanese citizens are very adept and actions such as washing the hands before eating and bathing everyday are day-to-day habits, intrinsic to their culture. Traditional public hot springs were formerly used as places for bathing and remain in use to this day, for more relaxed moments. Furthermore, shoes are not permitted within houses.

Rules are very important in Japanese society. The vast majority of the population follow them. Be it speed limits, prohibition to speak on mobile telephones in public transports, respecting smoking areas, standing orderly in line, all of these rules, and many more, are very natural to the Japanese, and are diligently followed.

Another factor that cannot be forgotten is Japan's traditional diet20 and exercise culture. Japanese tend to eat little, many times a day, with rice being the basis of their meals. It is also common to accompany meals with green tea. As for exercise, team sports or individual sports are part of the daily life for all ages. It is not uncommon to see a whole family practicing sport on a weekend.

The Ni-Hon-San study, led in 1960, tried to evaluate the dietary and lifestyle differences between middle-aged Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and San Francisco, and how this influenced their risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality. Results showed that the Japanese men living in Hawaii had higher blood cholesterol levels and almost twice the rate of heart disease, while the fully Westernized Japanese men living in San Francisco had the highest blood cholesterol levels (nearly triple the rate of heart disease compared to the Japanese men living in Japan). Despite the Japanese not being genetically predisposed for cardiovascular diseases, this study demonstrates how the surroundings interact with health.

Currently Japan is facing a worsening performance in health. This can be partly explained by high levels of tobacco consumption, high rates of suicide and a slight increase of the body-mass index. It is also argued that the treatment for high cholesterol levels is lower in Japan than in other high-income societies. The economic stagnation and the rising income inequality are probably another two explanations of this trend.

On the other hand, if we choose to look at Portugal, we will see quite a different picture.

Portuguese culture is very different from Japanese culture. Portuguese people do not give as much importance to rules. There is no sports culture. Hygiene habits are lacking in some strata of the population and Portuguese people tend to lead a sedentary lifestyle. The Mediterranean diet is slowly being abandoned and replaced with less healthy eating habits, leading to a higher rate of obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2. Portuguese people attach a great deal of importance to their external appearance and to their perceived standing within the group.

Fact is, that life expectancy at birth in Portugal has improved dramatically over the past 25 years and perinatal and infant mortality rates were better than the European Union (EU) average in 2007. Death rates by diseases of the circulatory system (ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular accidents), all types of malignant neoplasms and respiratory system diseases were also considerably lower in Portugal than the EU average in 2006.

However, about 14% of Portuguese considered their own health as being “bad” or “very bad” in 2005/06. Despite this being a very subjective topic, Portugal had the lowest percentage of population who assessed their health as “good” within the other 13 EU 15 countries as no other country had a result of less than 50%. Overall, Portuguese do not trust their healthcare system to provide them good, accessible care when needed the most.

Inequalities in health status between men and women, as well as among geographical regions, are considerable. Following the general tendency, women do live longer than men, but most of them live in a poorer state of health and have both a shorter disability-free life expectancy and a lower self-assessed health status than men. Men who die at earlier ages are mostly due to suicide, motor vehicle accidents and HIV/AIDS. As for issue of geography, people living in less populated and less urbanized regions of Portugal have a shorter life expectancy than the others. Economical inequality is also a critical issue, as in the mid-2000s Portugal had the third highest rate of income inequality of the 30 OECD countries, ranking only lower than Mexico and Turkey. Furthermore, Portugal was eminent in income-inequality in terms of use of physician services for 13 of the EU 15 countries: ranking last for income-related inequality in use of specialist visits and second to last for use of general practitioners.

The rates of obesity have been increasing in all age groups and for both sexes. There's also no sign of improvement in the smoking rate in Portugal (it was registered a decrease among male smokers, but an exponential increase of female smokers) and, furthermore, it has been proven that the higher the education level, the higher the tobacco consumption is.

Regarding Portuguese healthcare, Portugal had the highest rate of amenable mortality among the EU 15 countries in 2002–2003 even if the total expenditure on health had been increasing considerably over the past decade. The total health care expenditures as a percentage of GDP grew from roughly 8.5% in 2000 to 9.5% in 2007, ranking Portugal as fifth highest among the EU 15 countries. Nevertheless, this expenditure is greatly because of the raise in private expenditure, reaching therefore disproportionate levels, posing as another disadvantage for poorer households and consequentially limiting the access to healthcare. Public expenditure on health decreased over the period of 2000–2007 from 73% to 70%, making Portugal the second lowest country in the EU 15. The percentage of health care spending devoted to primary care has decreased since 2001, too.

What happens is that part of the population is covered by a private subsystem, aside from the already existent public one, in order to have better medical care.

Furthermore, the Portuguese consume a high quantity of pharmaceuticals (specially antidiabetics, anticholesterols and antidepressants) when compared to other EU 15 states. This might be avoidable with a change of the population's habits and lifestyle and more strict prescription guidelines for physicians.

If we think of the overall economic context for health, the value for money and the financial sustainability of the Portuguese Health Care System is questioned.21

ConclusionHaving as the main target the wellbeing of the population, one can conclude that the Japanese Health Care System has many positive points, not only when it comes to how it works as how it is seen by society. For 50 years, while maintaining its egalitarian principles, it has tried to adapt itself to socio-economical changes, aging of the population and the challenges that surge from natural disasters, such as typhoons, tsunamis and earthquakes.

Meanwhile, the Portuguese Health Care System has had positive results, but those results have not had an effect on perception. What is more, the system is expensive to maintain, especially in a time of financial turmoil. Even if Portugal's GDP is smaller than Japan's, a country's GDP and, in particular, its potential GDP, limits the country's ability to invest sustainably, i.e. without increasing its debt to unsustainable levels through successive deficits.

Both systems are in the need of reform, being Portugal in a much direr situation than Japan. Portugal should learn from Japan's case and try to learn what it can from Japan's system to improve upon its own.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

A special thank you to Zao Zhang for his assistance with applying the poll to the Japanese population and preparing the interview with Go Tanaka, MD, MPH, PhD. I would also like to thank Dr Go Tanaka for his openness and for being available to answer all the questions.