The aim of this study consisted in the assessment of the prevalence of dental caries, dmft and DMFT index among schoolchildren and analysis of the association between oral health behaviors and socio-demographic aspects.

MethodsIn a cross-sectional study we assessed 605 children aged between 6 and 12 years from 27 public schools of Sátão, Portugal. Dental caries was assessed by performing an intraoral observation. Data concerning children's oral health behaviors and socio-demographic variables were collected through a questionnaire filled out by their parents. Prevalences were expressed in proportions. The continuous variables were described using the mean and standard deviation. The Chi-square test was used to compare proportions and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparing continuous variables.

ResultsWe verified that the dmft index was 3.01±3.03 and DMFT index was 0.93±1.35. The prevalence of dental caries is associated with age (≤8 years, 37.1% vs 40.0%, p=0.008), parents’ educational level (0–4 years, 4–9 years, >9 years, 41.2% vs 43.7% vs 13.8%, p=0.001) and residence area (rural, 42, 2% vs. 31.2%, p=0.003). Dental caries is also associated with oral health behaviors such as toothbrushing (twice or more times per day, 31.2% vs 42.2%, p=0.003), dental flossing (34.5% vs 42.3%, p=0.036) and frequent dental appointments (34.5% vs 41.2%, p=0.04).

ConclusionsWe found a moderate prevalence of dental caries and in early age children there is a high percentage with multiple dental caries. Dental caries is associated with socio-demographic and behavioral aspects.

O objetivo deste estudo consistiu na avaliação da prevalência da cárie dentária, índice cpod e CPOD em crianças em idade escolar e análise da associação entre os comportamentos de saúde oral e fatores sociodemográficos.

MétodosRealizou-se um estudo transversal numa amostra de 605 crianças com idades compreendidas entre os 6 e os 12 anos de 27 escolas públicas do concelho de Sátão, Portugal. A cárie dentária foi avaliada através da realização de uma observação intra-oral. Os dados relativos a comportamentos de saúde oral das crianças e variáveis sócio-demográficas foram recolhidos através de um questionário preenchido pelos pais. Prevalências foram expressas em proporções. As variáveis contínuas foram descritas utilizando a média e desvio padrão. Para comparação de proporções recorreu-se ao teste Qui-quadrado e o teste Kruskal–Wallis para comparação de variáveis contínuas.

ResultadosVerificou-se que o índice médio de cpod foi de 3,01±3,03 e índice CPOD foi de 0,93±1,35. A prevalência de cárie dentária está associada com a idade (≤8 anos, 37,1% vs 40,0%, p=0,008), o nível de escolaridade dos pais (0–4 anos,4–9 anos, >9 anos, 41,2% vs 43,7% vs 13,8%, p=0,001) e área de residência (rural, 42,2% vs 31,2%, p=0,003). A cárie dentária encontra-se também associada a comportamentos de saúde oral, como a escovagem (duas ou mais vezes por dia, 31,2% vs 42,2%, p=0,003), uso do fio dentário (34,5% vs 42,3%, p=0,036) e consultas regulares ao médico dentista (34,5% vs 41,2%, p=0,04).

ConclusõesEncontrámos uma prevalência moderada de cárie dentária em crianças bem como uma percentagem considerável com a presença de múltiplas lesões cariosas. A cárie dentária encontra-se associada a aspectos sócio-demográficos e comportamentais.

Oral pathologies, such as dental caries and periodontal diseases, are among the most prevalent worldwide.1 They are responsible for a high morbidity among the population, being associated with decreasing quality-of-life and direct and indirect costs, such as expensive treatments and labor and school absence.2,3

In most of the developed countries, the prevalence of high severity dental caries has been decreasing to moderate and low, while in developing countries there has been an increasing of its severity, from low to moderate.1,4 This is due to a group of preventive measures carried out in the populations, leading to a significantly improvement of their oral health.

Dental caries is a post-eruptive, infectious disease characterized by a gradual dissolution and destruction of the mineralized tissues of the teeth. Invariably, the absence of treatment will lead to worse and more extended lesions, progressing toward the dental pulp, resulting in a progressive increase of the pulp's inflammation, coexisting with pain symptomatology.5–7

With a etiology, affected by the modern society's numerous cultural, social and technological factors and being hard to explain its large variations in prevalence and incidence, dental caries is clinically characterized by a large polymorphism. Even today, it is a very complex pathological entity.6,7

Dental caries can be assumed as a real biosocial disease, whose complications, not only affect the individual and the community's health, but also has a negative social and economical impact, namely among school-age children.8

In Portugal, oral healthcare is largely provided by the private sector. However, the implementation of the National Oral Health Promotion Program has provided school-age children with the essential necessary oral healthcare. This program includes not only secondary prevention measures, but also primary prevention ones, such as topical fluoride application and fissure sealants. Over the years, this program has led to a significant reduction of dental caries prevalence in schoolchildren, credit to the care provided through the oral health promotion programs, both in primary and secondary prevention9.

In the last few years, the decrease of dental caries prevalence among Portuguese children is also explained by a significant enhancement of oral hygiene habits, the use of fluoride toothpastes and an increased availability of preventive treatments.9–11

Nevertheless, despite children and adolescents’ oral health improvement, the latest national survey on the prevalence of oral pathologies revealed that the DMFT registered in adolescents aged from 12 to 15 years old was 1.48 and 3.04, respectively. This study associates the risk of developing dental caries, among younger children, with age and a less favorable socio-economic status.11

Even if there is an oral health enhancement among children and adolescents in Portugal, it is important to mention poorer oral condition, among those who live in suburban areas, linked to a more narrowed access to medical and dental care. This situation justifies the Portuguese children's irregular and ineffective oral hygiene habits, when compared to children from other European countries.12

Therefore, several studies have established an association between the risk of developing dental caries, with poor oral hygiene habits and consuming sugary foods and drinks.2,3,9,10 A previous study concluded that children who brush their teeth less than once a day, that do not use fluoride toothpastes and consume soft drinks between meals, have a higher risk of dental caries development.13

Controlling and better understanding the harmful effects of an excessively cariogenic diet, improving oral hygiene habits and regular appointments to the dentist lead to a clear oral health improvement, especially among school-age children and adolescents. Several studies reported that a suitable oral health behavior during childhood perpetuates more effectively into adulthood, reducing significantly the risk of oral pathologies.12–15

As so, the objectives of this study were to determine the prevalence of dental caries, dmft and DMFT index in children of the public primary schools of the town of Sátão, Portugal, and correlate oral health indicators with oral health behaviors and socio-demographic aspects.

Materials and methodsAn epidemiological, observational, cross-sectional study was designed. Data collection was accomplished by an intraoral observation to assess dental caries and a questionnaire, for collecting data related with oral health behaviors and socio-demographic variables. The sample was constituted by children who attended the twenty-seven primary schools, of the town of Sátão, localized in the Central Region of Portugal. All students, from the selected schools, were eligible to participate in the study, since they attended primary school and were aged between 5 and 12 years old, obtaining a final sample of 605 children participating in the study.

The intraoral assessment was performed using a dental mirror and the WHO probe, and based on the diagnostic criteria recommended by the World Health Organization.16 The results were registered in the students in a individual oral status form and, for each child, was calculated the number of decayed teeth, missing due to caries and filled/restored due to dental caries for primary teeth (dmft) and permanent teeth (DMFT). Then, the dmft and DMFT index were calculated, consisting of the sample's total average number of teeth decayed, missed and filled. By determining the dmft and DMFT index, we can define four levels of dental caries prevalence severity:

- •

Very low prevalence: ≤1.1;

- •

Low prevalence: 1.2–2.6;

- •

Moderated prevalence: 2.7–4.4;

- •

High prevalence: 4.5–6.5;

- •

Very high prevalence: >6.5.1

Data regarding oral health behaviors and socio-demographic features was gathered through a questionnaire, answered by their parents, in the classroom. Data collection obtained by the questionnaire was: socio-demographic characteristics such as the child's schooling year, gender, date of birth, number of people living at home, number of siblings and of older brothers, amount of rooms in the house, with whom the children lived, occupation and parents’ educational level. The information assembled, on oral health behaviors, was obtained through questions concerning aspects such as: the number of daily brushings, time and way of conducting their oral hygiene, use of dental floss, teaching oral hygiene at home, dental appointments, oral health problems, other systemic diseases and food/diet.

To develop this study, it was necessary to send a formal authorization request to the Director of the Group of Schools of Sátão using a specific form (Ofício 335), submitted by the Director of the local Health Center. It was also requested parents’ written authorization to perform the intraoral observation and questionnaire response by free and informed consent, with the necessary enlightenment of what was going to be held. The information gathered was anonymous, voluntary and confidential. Data was numbered, stored and later processed by computer. The announcement of the results does not make nominal reference to children or likely to contain information identifying any participant.

The analysis of the collected data was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20.0® (SPSS 20.0®, Inc, Chicago, IL, EUA). The continuous variables were described using the mean and standard deviation. The Chi-square test was used to compare proportions and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparing continuous variables. The significance level that established the inferential statistics was 5% (p<0.05).

ResultsThis study included 605 children that were attending twenty-seven public primary schools, of the town of Sátão, in Portugal. The sample involved 35.7% children that lived in urban areas and 64.3% in rural areas. Forty-nine point six percent of the pupils were male and 50.4% were female, aged between 5 and 12 years old. Of the whole sample, 22.2% were attending the 1st grade, 26.1% the 2nd grade, 26.2% the 3rd grade and 25.5% the 4th grade.

Dental caries prevalence was 72.1%. Only 27.9% pupils were free of dental caries and about 47.0% had 3 or more dental caries, at the time of the intraoral observation.

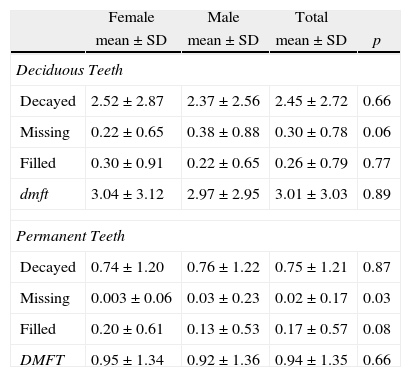

In our sample, we ascertained that dmft index was 3.01±3.03 and DMFT was 0.93±1.35, not having registered statistically significant differences between genders. The components analyzed, corresponding to decayed (D) missing (M) and filled (F) for deciduous and permanent teeth, are presented in Table 1.

Results for dmft index (deciduous teeth) and DMFT index (permanent dentition).

| Female | Male | Total | ||

| mean±SD | mean±SD | mean±SD | p | |

| Deciduous Teeth | ||||

| Decayed | 2.52±2.87 | 2.37±2.56 | 2.45±2.72 | 0.66 |

| Missing | 0.22±0.65 | 0.38±0.88 | 0.30±0.78 | 0.06 |

| Filled | 0.30±0.91 | 0.22±0.65 | 0.26±0.79 | 0.77 |

| dmft | 3.04±3.12 | 2.97±2.95 | 3.01±3.03 | 0.89 |

| Permanent Teeth | ||||

| Decayed | 0.74±1.20 | 0.76±1.22 | 0.75±1.21 | 0.87 |

| Missing | 0.003±0.06 | 0.03±0.23 | 0.02±0.17 | 0.03 |

| Filled | 0.20±0.61 | 0.13±0.53 | 0.17±0.57 | 0.08 |

| DMFT | 0.95±1.34 | 0.92±1.36 | 0.94±1.35 | 0.66 |

Dental caries prevalence was associated with the child's age, parental educational level and residence area. Children whose parents attended school up to the fourth grade had a higher risk of developing dental caries, contrasting with children whose parents had an educational level equal or above the ninth grade. Regarding residence area, it was possible to verify that children living in rural areas and as in advanced children's age, there was a higher frequency of developing dental caries (Table 2).

Association between the number of registered dental caries and socio-demographic features.

| 0 dental caries | 1 to 3 dental caries | ≥ 4 dental caries | p | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 28.0 | 33.1 | 38.9 | |

| Female | 27.9 | 34.4 | 37.7 | 0.94 |

| Age | ||||

| ≤8 years old | 32.4 | 30.5 | 37.1 | |

| >8 years old | 21.3 | 38.8 | 40.0 | 0.008 |

| Parent's educational level | ||||

| 0–4 anos | 23.5 | 35.3 | 41.2 | |

| 4–9 anos | 24.0 | 32.3 | 43.7 | |

| >9 anos | 49.4 | 36.8 | 13.8 | 0.001 |

| Residence area | ||||

| Rural | 23.6 | 34.2 | 42.2 | |

| Urban | 35.8 | 33.0 | 31.2 | 0.003 |

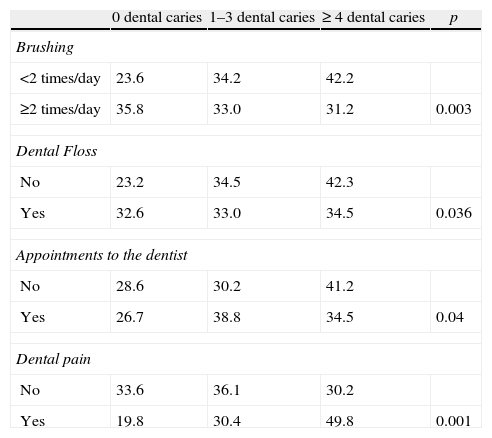

Concerning children oral health behaviors, we found that 53.9% brush their teeth twice or more times per day, which is considered as the basic rule of daily oral hygiene. Only 21.9% claimed to use dental floss, 53.2% do not use it and 24.9% said not knowing what dental floss is. As for appointments to the dentist, less than half of the children (41.4%) did one visit, in the last 12 months. From those who had seen the dentist, in that period of time, (33.2%) went there in an emergency situation, in the presence of a toothache (or dental pain). This situation is also sustained by the child's dental pain experience, considering that 42.5% had, at some period of his/her life, a situation of toothache.

When analyzing dental caries frequency, we noticed statistically significant differences between the frequency of daily brushing, the use (or not) of dental floss, a dental appointment in the last twelve months and the presence or absence of one or more episodes of toothache (Table 3).

Association between the number of registered dental caries, oral health behaviors and toothache.

| 0 dental caries | 1–3 dental caries | ≥ 4 dental caries | p | |

| Brushing | ||||

| <2 times/day | 23.6 | 34.2 | 42.2 | |

| ≥2 times/day | 35.8 | 33.0 | 31.2 | 0.003 |

| Dental Floss | ||||

| No | 23.2 | 34.5 | 42.3 | |

| Yes | 32.6 | 33.0 | 34.5 | 0.036 |

| Appointments to the dentist | ||||

| No | 28.6 | 30.2 | 41.2 | |

| Yes | 26.7 | 38.8 | 34.5 | 0.04 |

| Dental pain | ||||

| No | 33.6 | 36.1 | 30.2 | |

| Yes | 19.8 | 30.4 | 49.8 | 0.001 |

In this study, we registered a moderated dmft index. This value is very concerning given the children's very early age and the considerable prevalence of dental caries. Considering the children's early age, we must take into account the elevated DMFT's value corresponding to permanent teeth, which are just erupted teeth, as well as the oral health behaviors of the sample.

We can assume that a lower socio-economic status is related to a higher prevalence of dental caries.17 The differences arise when we analyze the variables “parent's educational level” and “residence area”. The results of this study demonstrate that children who live in Sátão, considered as an urban area, have a lower prevalence of dental caries compared to those living in the surrounding villages. This situation converges with the results of other studies already carried out.18,19

In this research, we also noticed deficient oral health behaviors that might explain the prevalence of dental caries. A correlation between an irregular brushing, the lack of using dental floss daily and a greater risk for dental caries development is evidenced by the results obtained. These results also reflect, to a large extent, the household's unawareness of oral health behaviors, having therefore serious limitations in conveying their children and younger relatives the essential information for a proper oral health.20

There should be particular attention to children from rural areas with low socio-economic conditions. It may reflect worse oral health behaviors and less frequent appointments to the dentist, resulting in an increased risk of dental caries.21–23

In a previous study, it was possible to determine the relationship between socio-economic status and a higher risk of developing oral pathology with painful symptomatology.24

When analyzing the variable “appointments to the dentist”, we found out that the children who reported not having visited a dentist, in the last twelve months, had a higher prevalence of dental caries and reflected a higher value of dmft and DMFT. When a dental caries is not promptly treated, it leads to an increased risk of painful symptomatology and the socio-economic status turns out to be a barrier to seeking dental care.25

Currently, it is essential to make regular studies concerning the major oral disorders’ behavior, allowing the planning of appropriate actions to be developed in the oral health field. A health policy based on educating children, adolescents and their own family, in order to have a balanced diet, with reduced consumption of sugary foods and beverages, as well as improving their oral hygiene habits and regular dental appointments are key points that can contribute to a decrease of oral diseases.26

ConclusionsWe found a moderate prevalence of dental caries in deciduous teeth and a very low prevalence of dental caries among permanent teeth in a sample of schoolchildren aged between 5 and 12 years old. However in early age children there is a high percentage with multiple dental caries. Dental caries is associated with socio-demographic and behavioral aspects. Considering the existence of changeable etiological factors of dental caries, nowadays, it is crucial to conduct regular studies concerning the major oral pathologies and associated risk behaviors, allowing a proper planning of actions to be carried out in the oral health field. It is crucial the implementation of primary prevention methods, in order to avoid the onset of the pathology and not merely the secondary prevention aiming to “catch” the disorder when it already exists.

If one of the primary healthcare goals is the decrease of social inequalities among individuals, particularly regarding oral health, it will be necessary to strengthen attention in what concerns the oral healthcare, because the accessibility to such care might be reflected into valid and effective results for the individuals’ overall health.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.