To analyse the potential effects of menopause on tooth loss in women with chronic periodontitis.

MethodsThe study included 102 women between 35 and 80 years old with chronic periodontitis and at least six teeth divided into two groups: the study group (SG), which consisted of 68 menopausal women, and the control group (CG), which consisted of 34 pre-menopausal women. Each participant was given a survey to collect several demographic data points, general and oral clinical histories, gynaecological history and behavioural habits. Several oral and periodontal measurements were recorded, including the number of teeth, plaque index, presence of calculus, probing depth, bleeding on probing, gingival recession and attachment loss. The following statistical tests were used: Chi-square, Fisher, t-test for independent samples, Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney non-parametric test and ANCOVA.

ResultsAt least one tooth was missing in 98% of the women in the study. The SG exhibited significantly fewer teeth than the CG (SG 10.83±5.90, CG 6.79±4.66), but the difference was not significant after adjusting for age (p<0.05). On the other hand, significant difference was not observed between the groups for the major periodontal measurements taken.

ConclusionsMenopause did not appear to significantly affect tooth loss in the study population. The effect of menopause is likely small compared with other clinical and socioeconomic factors.

Analisar o possível efeito da menopausa sobre a perda dentária em mulheres com periodontite crónica.

MétodosCento e duas mulheres entre os 35-80 anos com periodontite crónica e pelo menos 6 dentes foram divididas em 2 grupos: grupo de estudo (GE) constituído por 68 mulheres na menopausa e grupo controlo (GC) constituído por 34 mulheres pré-menopáusicas. Foi aplicado um questionário onde se recolheram diversos dados sociodemográficos, história clínica geral e oral, antecedentes ginecológicos e hábitos. Adicionalmente, foram avaliados diversos parâmetros orais e periodontais incluindo: número de dentes, índice de placa, presença de tártaro, profundidade de sondagem, hemorragia à sondagem, recessão gengival e perda de inserção. Na análise estatística foram utilizados os testes de Chi-Quadrado, Fisher, teste-t para amostras independentes, teste não-paramétrico de Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney e ANCOVA.

ResultadosNoventa e oito por cento das mulheres estudadas apresentam pelo menos um dente ausente. Ao comparar o grupo de mulheres pré e pós-menopáusicas, o número de dentes é significativamente menor nas mulheres na menopausa (GE 10,83±5,90; GC 6,79±4,66), no entanto, depois de ajustado o efeito da idade esta diferença deixa de ser estatisticamente significativa (p<0,05). Por outro lado, não se observam diferenças significativas entre os 2 grupos em relação aos principais parâmetros periodontais avaliados.

ConclusõesNa população estudada a menopausa não parece influenciar significativamente a perda dentária. Comparativamente a outros fatores socioeconómicos e clínicos, o efeito na menopausa na doença periodontal será provavelmente reduzido.

After menopause, oestrogen production decreases significantly, which is thought to be the major cause of primary osteoporosis.1,2 Reduced bone density in the jaws may be linked to increased risk of tooth loss in individuals without periodontal disease or increased disease severity in individuals with periodontitis.3 The potential link between osteoporosis and periodontal disease has generated significant interest because these two disease share several risk factors in addition to bone loss.

Several studies have shown a connection between decreased skeletal bone mineral density (BMD) and decreased numbers of teeth,4–9 while other studies have not shown this relationship.10–13 Studies analysing the relationship between decreased systemic BMD and periodontal disease progression have also found contradicting results.5,9,11,13–15 In addition to the effects on bone, oestrogens may also interfere with other periodontal tissues (gingiva and periodontal ligament) and affect the immune-inflammatory response of the patient.16–18 Improvements in periodontal measurements,19,20 and tooth retention21–23 have also been reported in women undergoing hormone replacement therapy (HRT), although studies with contradicting results also exist.24,25

After more than 20 years, the relationship between menopause, osteopenia, osteoporosis and tooth loss remains somewhat controversial.

The aim of this study was to analyse the potential effects of menopause on tooth loss by comparing several general, oral and periodontal measurements between two groups of women (pre- and post-menopausal) with chronic periodontitis.

Materials and methodsThis cross-sectional study was performed at the Instituto Superior de Ciências da Saúde Egas Moniz (Monte da Caparica, Portugal) with prior approval from the Institution's Ethics Committee.

Women between 35 and 85 years old who had at least 6 teeth, had been diagnosed with chronic periodontitis and had not been treated during the last year were selected from patients referred for periodontal evaluation. Women within any of the following categories were excluded: diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis, refusal to sign the informed consent form, current participation in another study or incomplete survey or periodontal exam.

Of the 111 women chosen to participate in the study, eight did not meet the inclusion criteria, and one declined to participate, which resulted in a final sample of 102 patients. The patients were divided into two groups based on their menopausal state: a study group (SG) consisting of 68 postmenopausal women and a control group (CG) with 34 premenopausal women.

A woman was considered to be in menopause if had not menstruated for more than one year or had had a hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy.26

The criteria defined by the periodontal disease surveillance workgroup at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were used to diagnose periodontal disease.27

A survey consisting of 48 questions covering several areas (personal, socioeconomic, medical history, current medication, habits and lifestyle, dental history and oral hygiene routines) was administered to all of the participants. The gynaecological history was also recorded to determine hormonal exposure levels (age of menarche, number of pregnancies, number of births, age of menopause and oral contraceptive or hormone replacement use for longer than 6 months).

All oral and periodontal measurements were performed by a single examiner (R.C.A.) who was blind to the data obtained from the survey and the menopausal status. The examiner was trained before the beginning of the study by an experienced observer until their measurements agreed more than 90% of the time. The measurements were considered to agree when they were ≤1mm different. The calibration process was performed 15 days before the study began using 10 volunteer patients. The intra- and inter-examiner consistency was measured using the method proposed by Bland and Altman,28 and a high level of consistency was achieved for both the probing depth and gingival recession measurements.

The decayed, missing or filled (DMF) index,29 and the presence of fixed or removable prostheses was recorded. All the teeth that were completely erupted, excluding the third molars, retained roots and implants, were included in the analysis. The exam began with analysis of the presence of supragingival calculus (absent/present) and calculation of the Simplified Plaque Index.30

Probing depth (PD), defined as the distance in millimetres from the gingival margin to the bottom of the pocket was measured at six locations per tooth using a CP-12 graduated periodontal probe (Hu-Friedy®, Chicago, IL, USA). Simultaneously, the locations that bled after probing (BOP) were recorded. Gingival recession (REC), defined as the distance from the cementoenamel junction to the gingival margin was also measured at six locations per tooth. The sum of the PD and REC values was used to calculate the clinical attachment loss (CAL) at each location. The mobility of all the teeth and the presence of furcation defects in the molars were also determined.

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed using all the variables including the averages, standard deviations, intervals and percentages.

For qualitative variables (nominal and ordinal), the Chi-square and Fisher tests were used. Quantitative variables (discrete or continual) were analysed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test or unpaired t-test. Covariance analysis (ANCOVA) was performed for tooth loss to control the effect of potential confounding variables (plaque index, tobacco consumption and age).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A significance level of α=0.05 was established for all tests (p<0.05).

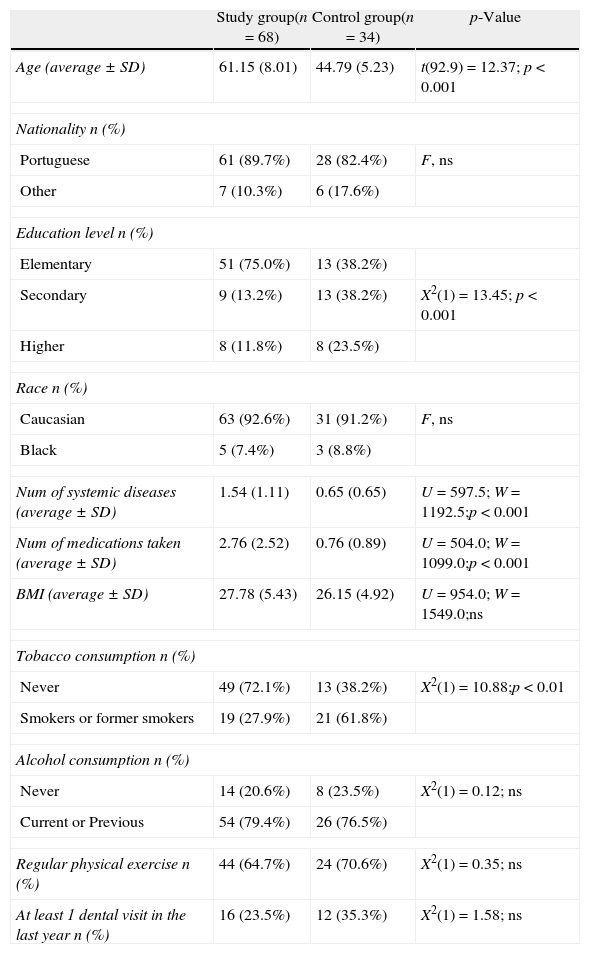

ResultsThe general characteristics of the study population are summarised in Table 1. The majority of the women were Caucasian (92.2%) and, as expected, the average age of the SG was significantly higher (p<0.001) than the CG (61.15±8.01 vs. 44.79±5.23).

General characteristics of the study population (n=102).

| Study group(n=68) | Control group(n=34) | p-Value | |

| Age (average±SD) | 61.15 (8.01) | 44.79 (5.23) | t(92.9)=12.37; p<0.001 |

| Nationality n (%) | |||

| Portuguese | 61 (89.7%) | 28 (82.4%) | F, ns |

| Other | 7 (10.3%) | 6 (17.6%) | |

| Education level n (%) | |||

| Elementary | 51 (75.0%) | 13 (38.2%) | |

| Secondary | 9 (13.2%) | 13 (38.2%) | X2(1)=13.45; p<0.001 |

| Higher | 8 (11.8%) | 8 (23.5%) | |

| Race n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 63 (92.6%) | 31 (91.2%) | F, ns |

| Black | 5 (7.4%) | 3 (8.8%) | |

| Num of systemic diseases (average±SD) | 1.54 (1.11) | 0.65 (0.65) | U=597.5; W=1192.5;p<0.001 |

| Num of medications taken (average±SD) | 2.76 (2.52) | 0.76 (0.89) | U=504.0; W=1099.0;p<0.001 |

| BMI (average±SD) | 27.78 (5.43) | 26.15 (4.92) | U=954.0; W=1549.0;ns |

| Tobacco consumption n (%) | |||

| Never | 49 (72.1%) | 13 (38.2%) | X2(1)=10.88;p<0.01 |

| Smokers or former smokers | 19 (27.9%) | 21 (61.8%) | |

| Alcohol consumption n (%) | |||

| Never | 14 (20.6%) | 8 (23.5%) | X2(1)=0.12; ns |

| Current or Previous | 54 (79.4%) | 26 (76.5%) | |

| Regular physical exercise n (%) | 44 (64.7%) | 24 (70.6%) | X2(1)=0.35; ns |

| At least 1 dental visit in the last year n (%) | 16 (23.5%) | 12 (35.3%) | X2(1)=1.58; ns |

BMI, body mass index; F, Fisher test; ns, not significant; t, unpaired t-test; U, W, non-parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test; X2, Chi-square test.

The most commonly used medications for osteoporosis treatment (limited to current use by the study group) were bisphosphonates (11.74%), followed by HRT (4.41%). When past HRT use is included in the analysis, the percentage of users increases to 26.47%. Only 4 women (5.88%) used calcium supplements, and no women used vitamin D supplements.

Although the body mass index was not significantly different between the groups, the large majority of women in the study were overweight or obese (SG 70.6%; CG 52.9%).

Almost two times more smokers or ex-smokers were assigned to the CG compared with the SG (SG 27.9%; CG 61.8%). In addition, we found that the number of packs/year was significantly higher in the CG (SG 3.02±8.25; CG 7.45±10.73, p<0.001).

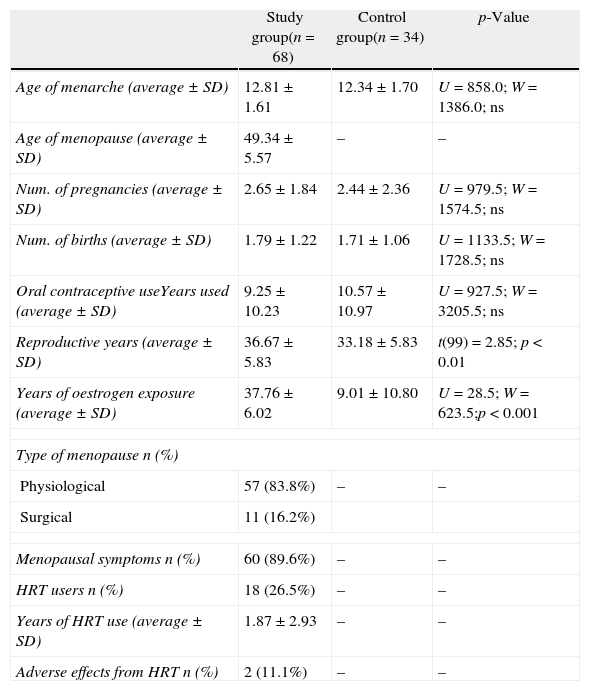

Analysis of the hormonal history (Table 2) shows that the age of menarche was similar between the two groups (SG 12.81 years of age; CG 12.34 years of age). The average age of menopause was 49.34±5.57 years old, and 83.8% of the cases occurred naturally.

Hormonal history.

| Study group(n=68) | Control group(n=34) | p-Value | |

| Age of menarche (average±SD) | 12.81±1.61 | 12.34±1.70 | U=858.0; W=1386.0; ns |

| Age of menopause (average±SD) | 49.34±5.57 | – | – |

| Num. of pregnancies (average±SD) | 2.65±1.84 | 2.44±2.36 | U=979.5; W=1574.5; ns |

| Num. of births (average±SD) | 1.79±1.22 | 1.71±1.06 | U=1133.5; W=1728.5; ns |

| Oral contraceptive useYears used (average±SD) | 9.25±10.23 | 10.57±10.97 | U=927.5; W=3205.5; ns |

| Reproductive years (average±SD) | 36.67±5.83 | 33.18±5.83 | t(99)=2.85; p<0.01 |

| Years of oestrogen exposure (average±SD) | 37.76±6.02 | 9.01±10.80 | U=28.5; W=623.5;p<0.001 |

| Type of menopause n (%) | |||

| Physiological | 57 (83.8%) | – | – |

| Surgical | 11 (16.2%) | ||

| Menopausal symptoms n (%) | 60 (89.6%) | – | – |

| HRT users n (%) | 18 (26.5%) | – | – |

| Years of HRT use (average±SD) | 1.87±2.93 | – | – |

| Adverse effects from HRT n (%) | 2 (11.1%) | – | – |

ns, not significant; t, unpaired t-test; U, W, non-parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test.

The number of pregnancies, births and oral contraceptive use were not different between the pre- and post-menopausal women. Although the result was not statistically significant, women in the study group used oral contraceptives for fewer years and had more reproductive years due to their higher age.

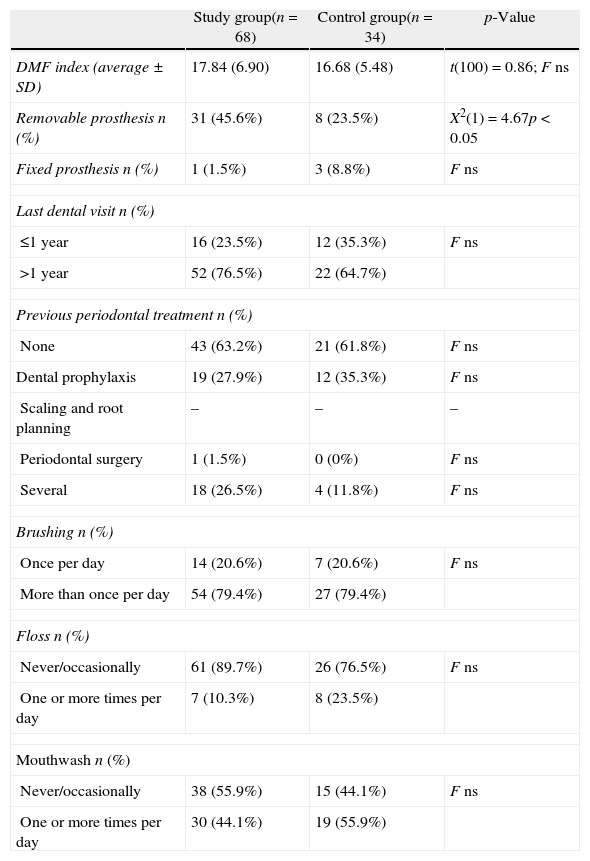

The percentage of restored or decayed teeth was similar between the groups, and the number of dental visits and types of previous periodontal treatments were also not significantly different (Table 3).

Oral parameters and dental hygiene routines.

| Study group(n=68) | Control group(n=34) | p-Value | |

| DMF index (average±SD) | 17.84 (6.90) | 16.68 (5.48) | t(100)=0.86; F ns |

| Removable prosthesis n (%) | 31 (45.6%) | 8 (23.5%) | X2(1)=4.67p<0.05 |

| Fixed prosthesis n (%) | 1 (1.5%) | 3 (8.8%) | F ns |

| Last dental visit n (%) | |||

| ≤1 year | 16 (23.5%) | 12 (35.3%) | F ns |

| >1 year | 52 (76.5%) | 22 (64.7%) | |

| Previous periodontal treatment n (%) | |||

| None | 43 (63.2%) | 21 (61.8%) | F ns |

| Dental prophylaxis | 19 (27.9%) | 12 (35.3%) | F ns |

| Scaling and root planning | – | – | – |

| Periodontal surgery | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | F ns |

| Several | 18 (26.5%) | 4 (11.8%) | F ns |

| Brushing n (%) | |||

| Once per day | 14 (20.6%) | 7 (20.6%) | F ns |

| More than once per day | 54 (79.4%) | 27 (79.4%) | |

| Floss n (%) | |||

| Never/occasionally | 61 (89.7%) | 26 (76.5%) | F ns |

| One or more times per day | 7 (10.3%) | 8 (23.5%) | |

| Mouthwash n (%) | |||

| Never/occasionally | 38 (55.9%) | 15 (44.1%) | F ns |

| One or more times per day | 30 (44.1%) | 19 (55.9%) | |

DMF, decayed missing filled index; F, Fisher test; ns, not significant; t, unpaired t-test; X2, Chi-square.

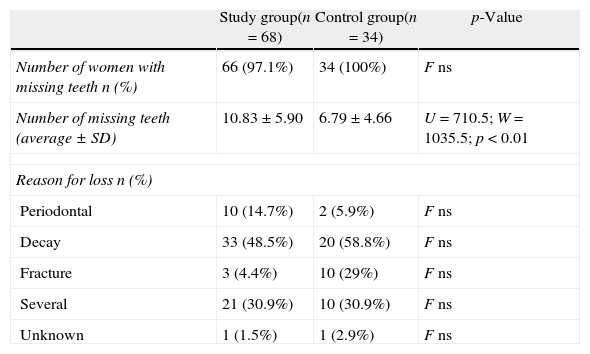

The SG exhibited fewer teeth compared with the CG (p<0.01), but the reason for tooth loss was the same in both groups (Table 4). Although the difference was not statistically significant, the number of teeth lost for periodontal reasons was slightly higher in the SG.

Comparison of the number of teeth in pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women.

| Study group(n=68) | Control group(n=34) | p-Value | |

| Number of women with missing teeth n (%) | 66 (97.1%) | 34 (100%) | F ns |

| Number of missing teeth (average±SD) | 10.83±5.90 | 6.79±4.66 | U=710.5; W=1035.5; p<0.01 |

| Reason for loss n (%) | |||

| Periodontal | 10 (14.7%) | 2 (5.9%) | F ns |

| Decay | 33 (48.5%) | 20 (58.8%) | F ns |

| Fracture | 3 (4.4%) | 10 (29%) | F ns |

| Several | 21 (30.9%) | 10 (30.9%) | F ns |

| Unknown | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | F ns |

F, Fisher test; ns, not significant; U, W, non-parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test.

Bacterial plaque accumulation is strongly correlated with periodontal disease and dental caries, and these two diseases are the major causes of tooth loss. To test the effects of the covariates plaque level, tobacco smoking and age on tooth loss, a covariance analysis was performed. The number of missing teeth was influenced by the menopausal state even after adjusting for plaque level (FSnedecor(1)=15.83, p<0.001) and tobacco smoking (FSnedecor(1)=10.39, p<0.01). However, after controlling for age, the tooth loss was not significantly different between the groups (FSnedecor(1)=0.31, ns).

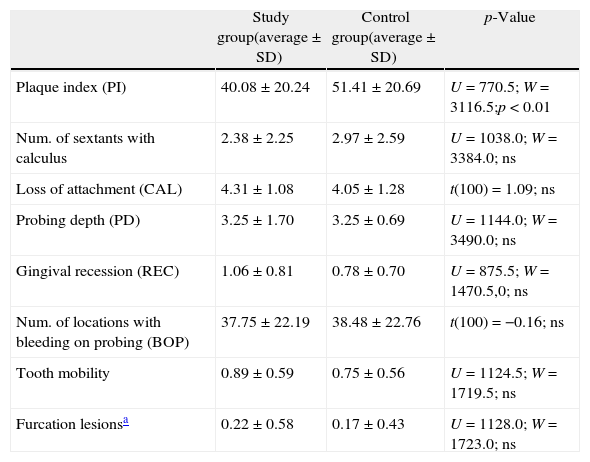

The periodontal measurements are shown in Table 5. The amount of bacterial plaque was higher in the CG (p<0.01) in contrast to the number of sextants with calculus, which was similar between the groups. A significant difference was not observed between the groups for the major periodontal measurements taken except for a higher percentage of locations with PD>4mm in the CG (p<0.05).

Distribution of periodontal variables in pre- and post-menopausal women.

| Study group(average±SD) | Control group(average±SD) | p-Value | |

| Plaque index (PI) | 40.08±20.24 | 51.41±20.69 | U=770.5; W=3116.5;p<0.01 |

| Num. of sextants with calculus | 2.38±2.25 | 2.97±2.59 | U=1038.0; W=3384.0; ns |

| Loss of attachment (CAL) | 4.31±1.08 | 4.05±1.28 | t(100)=1.09; ns |

| Probing depth (PD) | 3.25±1.70 | 3.25±0.69 | U=1144.0; W=3490.0; ns |

| Gingival recession (REC) | 1.06±0.81 | 0.78±0.70 | U=875.5; W=1470.5,0; ns |

| Num. of locations with bleeding on probing (BOP) | 37.75±22.19 | 38.48±22.76 | t(100)=−0.16; ns |

| Tooth mobility | 0.89±0.59 | 0.75±0.56 | U=1124.5; W=1719.5; ns |

| Furcation lesionsa | 0.22±0.58 | 0.17±0.43 | U=1128.0; W=1723.0; ns |

Some authors have suggested that tooth loss with age is due to alveolar bone loss caused by systemic bone loss and to local factors (periodontal disease).

Tooth loss may be linked to overall health deterioration through changes in eating habits.31,32 However, the body mass index of the population studied was high despite the high number of missing teeth, suggesting that this relationship is not linear.

Most of the women in the study population had at least one missing tooth, and the number of missing teeth was higher in the SG (10.83±5.90 vs. 6.79±4.66; p<0.01). The prevalence of dental caries and the differences in the periodontal measurements between the two groups do not fully explain the discrepancy in the number of missing teeth. Using tooth loss as a surrogate measure of periodontal disease has several limitations.33 The number of teeth is an indicator of the cumulative effects of oral health conditions over time.4 In addition, tooth loss is a complex phenomenon that is likely linked to various factors including genetics, nutrition, oral hygiene, healthcare access and tobacco smoking. After adjusting for the effects of age, we found that the number of missing teeth was independent of menopausal state.

Unlike us, Musacchio et al. observed that ageing, years since menopause (>23), number of children (>3) and social isolation are independent risk factors for tooth loss.34 Subsequently, Meisel et al. also found an inverse relationship between the number of teeth and the number of children, but the difference of approximately one tooth per child only applied to socioeconomically poor women that did not use HRT.35

Bollen et al. showed that age and tobacco smoking greatly affected the number of teeth in an elderly population in contrast to a history of osteoporotic fractures.36 On the other hand, Nicopoulou-Karayianni et al. showed that women with osteoporosis have fewer teeth than those with osteopenia or with a normal BMD even after adjusting for tobacco consumption and age.8

Similarly, Inagaki et al. found a correlation between decreased BMD and fewer teeth only in women with an average age of 63. According to these authors, this fact is not surprising because they had been exposed to the possible deleterious effects of osteoporosis for longer periods of time.37

In young women, Earnshaw et al. concluded that tooth loss depends more on dietary habits and previous treatments than on bone loss with age.10

However, in certain populations, tooth loss is inextricably connected with economic issues and dental treatment decisions. Some teeth are also extracted for reasons unrelated to disease (orthodontic or prosthetic reasons, for example).

Although some authors have suggested that tooth loss could be used as an indicator for decreased BMD and to decide who could benefit from a densitometry test, others consider that using tooth loss alone as a screening tool is not very precise.37

The limitations of this study include the fact that the measurements for bone density or height were not taken and that menopausal state and HRT use were based on self-reporting. However, self-reporting continues to be widely used in epidemiological studies because measuring hormone levels is time-consuming and expensive. Furthermore, a single measurement of hormone levels cannot show the oestrogen exposure over a lifetime. Several studies have found a high degree of concordance between self-reported data on HRT use and medical records.22

It is possible that the methodology used in this study recruited people who were more concerned with their health and had more access to medical care. Because the study population is not representative of the Portuguese population, the data shown here cannot be extrapolated to the population in general. Therefore, additional studies with larger sample sizes and longer observation times are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

ConclusionsMenopausal women have fewer teeth than premenopausal women, but the reasons for the teeth loss are similar in both groups. After adjusting for age, the number of missing teeth was not affected by menopausal state. The effect of menopause is likely small compared with other clinical and socioeconomic factors.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.