To determine the occurrence of clinical signs of dysphagia in infants with acute viral bronchiolitis, to compare the respiratory parameters during deglutition, and to ensure the intra- and inter- examiners agreement, as well as to accomplish intra and interexaminators concordance of the clinical evaluation of the deglutition.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study of 42 infants aged 0-12 months. The clinical evaluation was accompanied by measurements of respiratory rate and pulse oximetry. A score of swallowing disorders was designed to establish associations with other studied variables and to ensure the intra- and interrater agreement of clinical feeding assessments. Caregivers also completed a questionnaire about feeding difficulties. Significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsChanges in the oral phase (prolonged pauses) and pharyngeal phase (wheezing, coughing and gagging) of swallowing were found. A significant increase in respiratory rate between pre- and post-feeding times was found, and it was determined that almost half of the infants had tachypnea. An association was observed between the swallowing disorder scores and a decrease in oxygen saturation. Infants whose caregivers reported feeding difficulties during hospitalization stated a significantly greater number of changes in the swallowing evaluation. The intra-rater agreement was considered to be very good.

ConclusionsInfants with acute viral bronchiolitis displayed swallowing disorders in addition to changes in respiratory rate and measures of oxygen saturation. It is suggested, therefore, that infants displaying these risk factors have a higher probability of dysphagia.

Determinar a ocorrência de sinais clínicos de disfagia em lactentes com bronquiolite viral aguda e comparar os parâmetros respiratórios entre as fases da deglutição, assim como realizar a concordância intra e interexaminadores da avaliação clínica da deglutição.

MétodosEstudo transversal, com 42 lactentes, entre zero e 12 meses. A avaliação clínica da deglutição foi acompanhada das medidas da frequência respiratória e oximetria de pulso. Foi elaborado um escore de alterações de deglutição para estabelecer associações com demais variáveis do estudo e, para a avaliação clínica, realizada a concordância intra e interexaminadores. Os cuidadores responderam a um questionário sobre dificuldades de alimentação. O nível de significância utilizado foi p<0,05.

ResultadosForam encontradas alterações na fase oral (pausas prolongadas) e faríngea (respiração ruidosa, tosse e engasgos) da deglutição. Houve aumento significativo da frequência respiratória entre o momento pré e pós-alimentação, e quase metade dos lactentes apresentou taquipneia. Observou-se associação entre o escore de alterações de deglutição e a queda de saturação de oxigênio. Os lactentes cujos cuidadores relataram dificuldades de alimentação durante a internação tiveram um número maior de alterações de deglutição na avaliação. A concordância intraexaminador foi considerada muito boa.

ConclusõesLactentes com bronquiolite viral aguda apresentaram alterações de deglutição, acrescidas de mudanças na frequência respiratória e nas medidas das taxas de saturação de oxigênio. Sugere-se, assim, risco para a disfagia.

Acute viral bronchiolitis (AVB) is a common infectious disease of the lower airways that affects mostly infants younger than 1 year. The disease is characterized by diffuse bronchiolar inflammation induced by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in 60% to 70% of cases.1 Infants with AVB show wide variability in disease severity. Although prematurity, congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, and immunodeficiency are known risk factors,2 half of the infants who require hospitalization in intensive care units were full-term and previously healthy.3

The diagnosis of AVB is usually clinical, characterized by a first episode of wheezing in infants, accompanied by runny nose, cough, and fever.2,4,5 As the disease progresses, tachypnea and wheezing may appear, along with increasing respiratory distress and contraction of the respiratory muscles during inspiration.4,5 In the acute phase, bronchio-litis is often associated with nasal congestion, irritability, and feeding problems.6

Deglutition disorders in respiratory diseases are a more common complication than previously acknowledged, especially when associated with AVB.6–8 The risk of aspiration in infants with AVB has been reported,6–8 showing the possible interference of the respiratory symptoms in the deglutition process. A pioneer study6 on this subject often cited in the literature indicates the presence of laryngeal pene-tration and tracheal aspiration in previously healthy and medically stable infants, who had difficulty feeding during hospitalization. In another study,8 there was an association between tracheal aspiration and respiratory worsening of infants with AVB.

Dysphagia or deglutition disorder occurs when there is problem in one or more stages of swallowing and food bolus transportation; the lack of synchrony or coordination of these phases can lead to aspiration.9 The need to coordinate the respiratory difficulty with deglutition forces the child to adapt to the complex process of swallowing.10 The hypothesis is that infants with AVB suffer a deterioration arising from a compromised respiratory status. Consequently, they may be at risk for dysphagia and aspiration, worsening the clinical condition.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the occurrence of clinical signs of dysphagia in infants with AVB, and, as secondary objectives, to compare respiratory parameters between pre-feeding, feeding, and post-feeding stages and to perform the intra- and interrater agreement of deglutition assessment.

MethodBetween July and September 2012, 42 infants diagnosed with AVB, younger than 12 months and admitted at Hospital da Criança Santo Antônio were selected. The study prospectively included infants who were born at term or with gestational age ≥34 weeks, previously healthy from the respiratory point of view and who were receiving oral diet. Exclusion criteria were diagnosis or investigation of neurological, cardiac, and genetic problems; presence of craniofacial malformations; use of prokinetics and antacids or diagnosis of GERD performed by esophageal pH monitoring; need for invasive mechanical ventilation during hospitalization; use of feeding tube; and oxygen therapy >1 liter. Children with signs of sedation or deep sleep during the evaluation were also excluded, or those in whom it was not possible to conduct all phases of the research.

The evaluation of infants, according to the abovementioned criteria, was performed within 48 hours after hospital admission. Initially, infants with a clinical diagnosis of AVB performed by a pediatrician were selected, considering saturation level, respiratory frequency and effort as markers.11

The AVB diagnosis was confirmed by direct immunofluorescence in nasopharyngeal secretions and, when necessary, by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

The infants' parents or guardians answered a closed-ended questionnaire with information about the health history, previous and current feeding behavior, and the presence of clinical suspicion related to the exclusion criteria. Subsequently, the clinical characterization protocol was filled out, adapted from a form commonly used in the area of dysphagia,12 when data on ventilatory support, oxygen saturation (SpO2), and respiratory rate (RR) were collected. The measurement of SpO2 was identified numerically in the pre-, peri-, and post-feeding periods through a digital MiniScope II oximeter (Instramed, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil). A reduction in saturation was considered as a decrease >4% of the baseline after oral supply.13,14

The RR was measured in pre and post-feeding periods, considering as RR increase values ≥10%. Finally, the values were also compared to those indicated in the literature as tachypnea,15 considering 60 mpm for infants aged 0-60 days, and 50 mpm for those aged ≥60 days.

Before carrying out the swallowing clinical assessment (SCA), the structural evaluation was performed, regarding the morphology of the oral structures. In the SCA, the parent or guardian was instructed to feed the child, either by breastfeeding or formula offered in the bottle, in the usual position. When necessary, the formula was prepared according to the medical prescription in thin liquid consistency. The assessments were always performed at the usual times, with the three-hour diet interval. In the case of breastfeeding, a minimum interval of two hours after the last feeding was requested.

In the oral phase of swallowing, the parameters of maintenance of labial sealing, tongue movement, and fluid loss through labial commissures were identified. The sucking pattern was analyzed by the categories of presence, rhythm, occurrence and extent of pauses. The suction rate was based on the counting of sucking movements and pauses, identifying the regularity of the pauses between the sucking bouts. For the extent of the pause, the time interval between sucking bouts was recorded, and time interval ≥5 seconds was considered a long pause.

The coordination sucking-swallowing-breathing (CSSB) was defined based on the balance between feed efficiency and functions of sucking, swallowing, and breathing without signs of stress. In the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, the parameters presence of wheezing, gagging, coughing, wet voice, and multiple deglutitions during feeding were evaluated. Changes in skin color and the occurrence of flaring nose, watery eyes, and agitation were also identified. Multiple deglutitions were defined as the presence of two or more swallowing movements that occurred without a breathing period.

After a collection, a score related the number (%) of swallowing disorders found in SCA was assigned, ranging from zero to six altered clinical signs.

Based on the literature data, the following alterations were selected: wheezing, coughing, gagging, altered pause – either present or absent, as well as its length – sucking rhythm, and CSSB. The parameters coughing, gagging, and wheezing are often mentioned as indicators of risk of aspiration.16,17 Regarding the other parameters, they more specifically characterize the association between breathing and swallowing in the feeding process. Based on this score, the associations with the variables were determined: age, length of hospital stay, feeding difficulties, use of feeding tube and oxygen, food type, SpO2 rate, and RR.

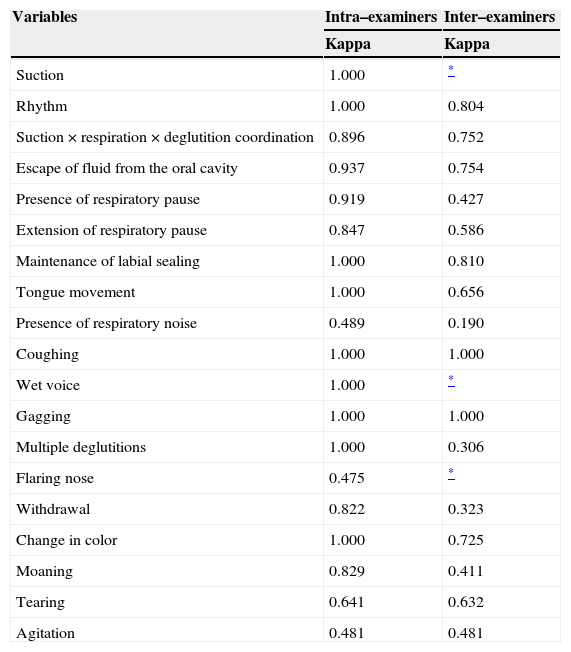

Intra- and inter-rater agreements were also evaluated. For that purpose, the initial protocol of clinical evaluation of swallowing was reduced, using as criteria items that could be reproduced in video, such as nutritive sucking pattern, movement of the tongue and lips during feeding, and deglutition assessment during the oral and pharyngeal phases. To assess the intra-rater agreement, the researcher filled out the reduced protocol 30 days after collection, based on the video images. For the inter-rater agreement, a speech therapist specialized in child dysphagia was invited to perform an assessment based solely on the videos. The agreement was analyzed using the kappa coefficient, and was classified as : <0.2, poor; 0.21-0.40, weak; 0.41-0.60, moderate; 0.61-0.80, good; and ≥0.81, very good.18

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Complexo Hospitalar Santa Casa, protocol No. 39058, and all parents/guardians signed an informed consent prior to the assessment.

Sample size calculation was performed in relation to the number of swallowing disorders, as no references were found on the prevalence of clinical signs of dysphagia in this population, but aspiration and penetration, which were not exactly the assessed outcome. The sample size calculation, assuming a confidence level of 95%, with moderate correlation between the variables (≥0.5), indicated that it would be necessary to have at least 38 children to achieve a statistical power of 90%.19

The SPSS, release 18.0 for Windows (PASW Statistics for Windows, Chicago, USA), was used for statistical analysis. Quantitative variables were described by means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges, whereas qualitative variables were described by absolute and relative frequencies. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures with post-hoc Bonferroni test was used to compare saturation values.

Student's t-test for paired samples was used for the RR values, assessed at two moments. Pearson's chi-squared test was used to evaluate the association between qualitative variables, whereas the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the number of swallowing disorders between groups. Spearman's correlation test was used in the analyses of association between continuous and ordinal variables. The intra- and inter-rater agreement was assessed by the kappa coefficient, and the differences between raters were verified by McNemar's chi-squared test. The level of significance was 5% (p≤0.05).

ResultsThe initial sample consisted of 174 infants, but 132 met the exclusion criteria used in this study, totaling a final sample of 42 infants. The median age of the infants was 82 (p25=32, p75=156) days; the length of hospital stay, four days (p25=4, p75=5). Of the total, 57.1% were males. Viral screening through direct immunofluorescence identified that 71.4% of infants were infected with RSV and 7.15% with Parainfluenza virus 1, Parainfluenza 2, Parainfluenza 3, and Adenovirus. PCR was not performed on any infant.

Based on interviews with caregivers, it was identified that 37 (88.1%) patients had no previous complaints of feeding difficulties. However, in 36 cases (85.7%), caregivers reported feeding difficulties during the hospitalization period. Among the main difficulties mentioned, 24 (64.9%) reported fatigue, 19 (45.2%) cough and 17 (40.5%) gagging. For the study, 27 (64.3%) patients were breastfed and 15 (35.7%) were bottle-fed.

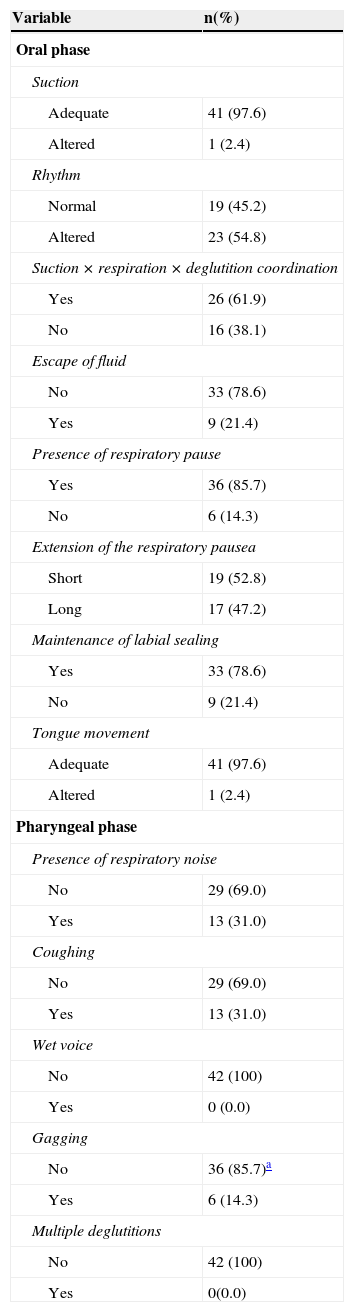

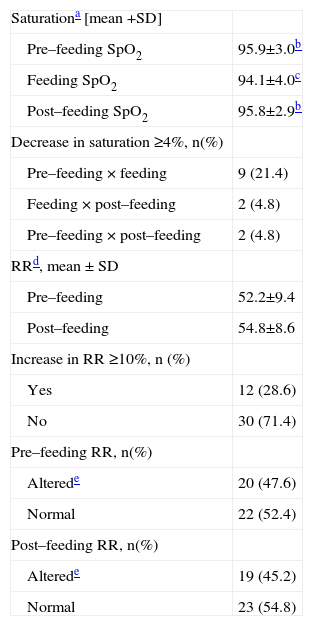

Clinical signs identified in the SCA, related to the oral and pharyngeal phase of swallowing, are shown in Table 1. At the moment of the assessment, 26 (60.5%) infants were receiving ventilatory support of up to 1 L of oxygen. There was a difference in the SpO2 rate between pre- and post-feeding, with a reduction in oxygen saturation at feeding time. RR significantly increased the number of breaths between the pre- and post-feeding time, as shown in Table 2. It could also be observed that almost half of the infants had tachypnea in the pre- and post-feeding moments.

Deglutition assessment in 42 infants with acute viral bronchiolitis

| Variable | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Oral phase | |

| Suction | |

| Adequate | 41 (97.6) |

| Altered | 1 (2.4) |

| Rhythm | |

| Normal | 19 (45.2) |

| Altered | 23 (54.8) |

| Suction × respiration × deglutition coordination | |

| Yes | 26 (61.9) |

| No | 16 (38.1) |

| Escape of fluid | |

| No | 33 (78.6) |

| Yes | 9 (21.4) |

| Presence of respiratory pause | |

| Yes | 36 (85.7) |

| No | 6 (14.3) |

| Extension of the respiratory pausea | |

| Short | 19 (52.8) |

| Long | 17 (47.2) |

| Maintenance of labial sealing | |

| Yes | 33 (78.6) |

| No | 9 (21.4) |

| Tongue movement | |

| Adequate | 41 (97.6) |

| Altered | 1 (2.4) |

| Pharyngeal phase | |

| Presence of respiratory noise | |

| No | 29 (69.0) |

| Yes | 13 (31.0) |

| Coughing | |

| No | 29 (69.0) |

| Yes | 13 (31.0) |

| Wet voice | |

| No | 42 (100) |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) |

| Gagging | |

| No | 36 (85.7)a |

| Yes | 6 (14.3) |

| Multiple deglutitions | |

| No | 42 (100) |

| Yes | 0(0.0) |

Clinical signs observed in the phonoaudiological evaluation

| Saturationa [mean +SD] | |

| Pre–feeding SpO2 | 95.9±3.0b |

| Feeding SpO2 | 94.1±4.0c |

| Post–feeding SpO2 | 95.8±2.9b |

| Decrease in saturation ≥4%, n(%) | |

| Pre–feeding × feeding | 9 (21.4) |

| Feeding × post–feeding | 2 (4.8) |

| Pre–feeding × post–feeding | 2 (4.8) |

| RRd, mean ± SD | |

| Pre–feeding | 52.2±9.4 |

| Post–feeding | 54.8±8.6 |

| Increase in RR ≥10%, n (%) | |

| Yes | 12 (28.6) |

| No | 30 (71.4) |

| Pre–feeding RR, n(%) | |

| Alterede | 20 (47.6) |

| Normal | 22 (52.4) |

| Post–feeding RR, n(%) | |

| Alterede | 19 (45.2) |

| Normal | 23 (54.8) |

SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation; SD, standard deviation; RR, respiratory rate;

With the proposed score, it was observed that nine (21.4%) patients showed no alterations in swallowing, and 33 (78.5%) had alterations that were distributed as follows: seven (16.7%) with one alteration, eight (19%) with two alterations, six (14.3%) with three alterations, seven (16.7%) with four alterations, and five (11.9%) with five alterations.

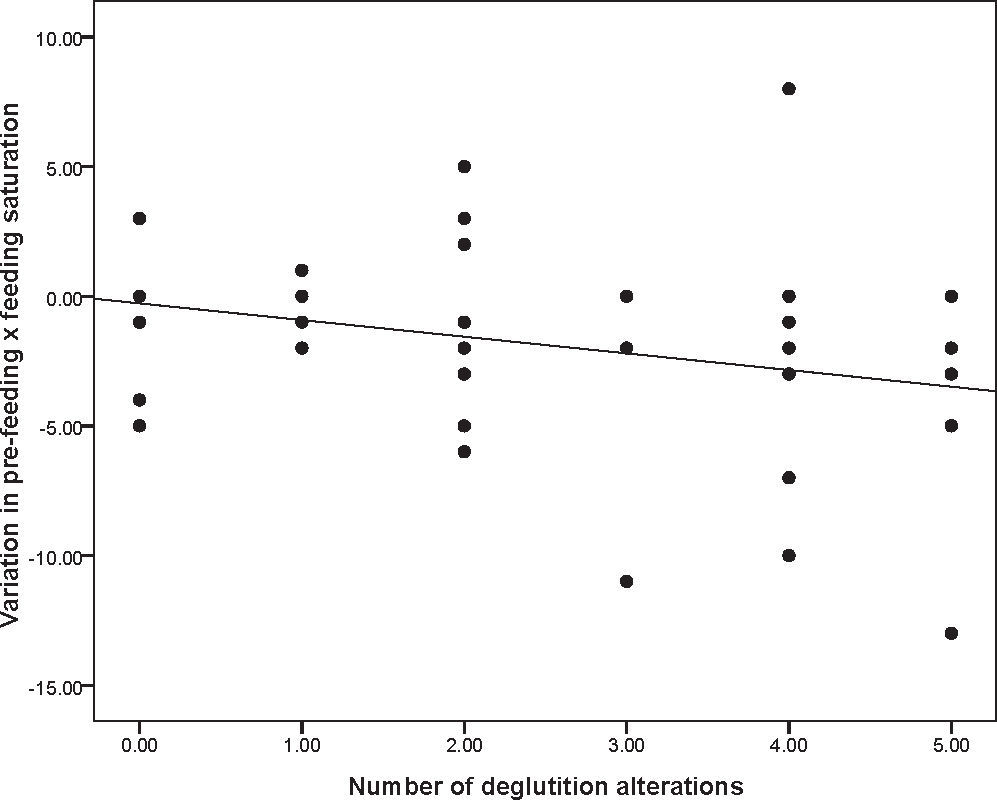

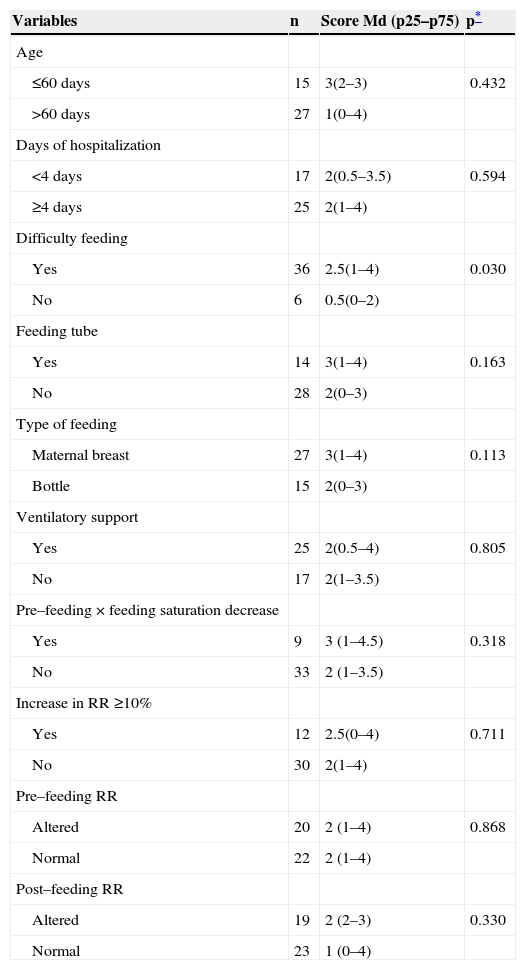

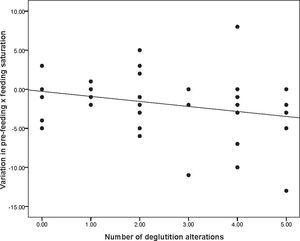

The associations between the alteration score proposed in the study and the analyzed variables are shown in Table 3. If there was a decrease in SpO2 expressed by numeric values, there was a significant association (rs=-0.305, p=0.050), i.e., the higher the number of swallowing disorders, the higher the reduction in oxygen saturation during feeding (Fig. 1). The association of the number of swallowing disorders with increasing RR was not significant (rs=0.215, p=0.172).

Association of study variables with the number of deglutition disorders

| Variables | n | Score Md (p25–p75) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≤60 days | 15 | 3(2–3) | 0.432 |

| >60 days | 27 | 1(0–4) | |

| Days of hospitalization | |||

| <4 days | 17 | 2(0.5–3.5) | 0.594 |

| ≥4 days | 25 | 2(1–4) | |

| Difficulty feeding | |||

| Yes | 36 | 2.5(1–4) | 0.030 |

| No | 6 | 0.5(0–2) | |

| Feeding tube | |||

| Yes | 14 | 3(1–4) | 0.163 |

| No | 28 | 2(0–3) | |

| Type of feeding | |||

| Maternal breast | 27 | 3(1–4) | 0.113 |

| Bottle | 15 | 2(0–3) | |

| Ventilatory support | |||

| Yes | 25 | 2(0.5–4) | 0.805 |

| No | 17 | 2(1–3.5) | |

| Pre–feeding × feeding saturation decrease | |||

| Yes | 9 | 3 (1–4.5) | 0.318 |

| No | 33 | 2 (1–3.5) | |

| Increase in RR ≥10% | |||

| Yes | 12 | 2.5(0–4) | 0.711 |

| No | 30 | 2(1–4) | |

| Pre–feeding RR | |||

| Altered | 20 | 2 (1–4) | 0.868 |

| Normal | 22 | 2 (1–4) | |

| Post–feeding RR | |||

| Altered | 19 | 2 (2–3) | 0.330 |

| Normal | 23 | 1 (0–4) |

RR, respiratory rate; Md, median; p25–75, 25th to 75th percentile.

Specifically regarding the agreement (Table 4), there was no significant difference between the two evaluations made by the same observer (p>0.05), with a very good intra-rater agreement in 15 (78.9%) items. Regarding the inter-rater agreement, there was a significant difference between the two raters regarding five items, as shown in Table 4.

Intra– and inter–examiner agreement

| Variables | Intra–examiners | Inter–examiners |

|---|---|---|

| Kappa | Kappa | |

| Suction | 1.000 | * |

| Rhythm | 1.000 | 0.804 |

| Suction × respiration × deglutition coordination | 0.896 | 0.752 |

| Escape of fluid from the oral cavity | 0.937 | 0.754 |

| Presence of respiratory pause | 0.919 | 0.427 |

| Extension of respiratory pause | 0.847 | 0.586 |

| Maintenance of labial sealing | 1.000 | 0.810 |

| Tongue movement | 1.000 | 0.656 |

| Presence of respiratory noise | 0.489 | 0.190 |

| Coughing | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Wet voice | 1.000 | * |

| Gagging | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Multiple deglutitions | 1.000 | 0.306 |

| Flaring nose | 0.475 | * |

| Withdrawal | 0.822 | 0.323 |

| Change in color | 1.000 | 0.725 |

| Moaning | 0.829 | 0.411 |

| Tearing | 0.641 | 0.632 |

| Agitation | 0.481 | 0.481 |

The data from this study contribute to current knowledge, as it has been demonstrated that alterations in swallowing, in the different phases, are present in infants with AVB, associating the data on feeding to respiratory aspects. Furthermore, it should be noted that if there is risk for dysphagia in these patients, therefore there may be aspiration, which would compromise the pulmonary aspect.

Based on the SCA, it was observed that infants with AVB had abnormal oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing during the hospitalization period. The increase in RR, the need for oxygen therapy, and fatigue during feeding interfered with swallowing. Although studies that addressed the risk of aspiration in infants with AVB6–8 used aspiration research methods that were different from the SCA, their results are in agreement with the present findings.

In this study, although certain aspects of the assessment of the oral phase of swallowing were preserved, such as the sucking pattern and the tongue movement, swallowing difficulties were observed, especially in relation to respiration. The variables rhythm and CSSB showed alterations in the evaluation of some infants. However, prolonged pauses during sucking were observed in almost half the sample. These findings are corroborated by another study10 that compared the feeding of infants with AVB to a control group of healthy infants and found no significant differences in the number of sucking movements per group, but observed longer resting periods between sucking bouts.

The data suggest that, as the respiratory effort increases, the deglutition sequence is modified, followed by inspiration or apnea, increasing the risk of aspiration. An apnea event in infants infected with RSV very often lasts longer than 30 seconds – when, in addition to central apnea, typical of the swallowing moment, an obstructive apnea occurs, generating a series of deglutitions or occasionally, coughs. Another aspect to be observed is that the pattern of long pauses, intermingled with a few sucking movements, can indicate immaturity or fatigue, due to specific clinical conditions.12 Fatigue was reported by caregivers as the most often perceived symptom of dysphagia, and it can generate aspiration risk at the swallowing phase during feeding.20

Regarding the results of the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, the occurrence of wheezing, coughing, and gagging was observed in part of the sample, which are shown in the literature as indicators of aspiration risk.16,20–22

Another study assessed the occurrence of clinical markers suggestive of deglutition disorders in infants, compared to the findings seen in the deglutition videofluoroscopy. Coughing, wheezing, and wet voice showed a significant association with aspiration in thin liquids; they were considered as good clinical markers of aspiration in infants. In addition, desaturation was identified as a marker, particularly in those younger than 12 months, considering that infants are more prone to silent aspiration. Thus, coughing is a less reliable indicator of aspiration in young infants.23

Considering that the SCA and the use of clinical signs are known to have low reliability in aspiration detection21 when compared to the objective evaluation of swallowing, it is emphasized that this is still the most accessible method for the everyday life of the hospital environment. After the occurrence of certain signs and symptoms at the time of feeding, the speech therapist is able to make inferences regarding the risk of aspiration. Based on the abovementioned facts and in order to make SCA more measurable, the observation of vital signs, such as respiratory rate and oxygen saturation measures, was used. The use of pulse oximetry as a resource for dysphagia assessment has been widely debated.

A recent study24 disclosed preliminary results suggesting that the mean number of desaturations can moderately discriminate infants with and without dysphagia, having a complementary role in SCA. In the present study, there was a significant decrease in oxygen saturation during feeding and recovery after oral feeding cessation.

Regarding the association with the alteration score, it was observed that infants with desaturation at the time of feeding had more swallowing disorders. RR, in turn, has not been regularly used in the protocols of swallowing assessment by speech therapists. In the literature,25 when RR exceeds 60-70 mpm in cases of AVB, food safety may be compromised, and thus intravenous fluids are recommended. The increase in RR, the alteration in times of inspiration and expiration, and decreased apnea time for swallowing considerably increase the possibility of aspiration.13,26

Infants whose caregivers reported feeding difficulties during hospitalization had a greater number of alterations in the swallowing assessment. The first step of speech therapy evaluation is to perform an interview on feeding difficulties.12 Thus, health teams should pay special attention when asking questions about nutrition to caregivers of infants hospitalized with AVB. The mothers' reports can signal the possibility of risk of aspiration and the need for specific swallowing assessment.

SCA is perceptual and, therefore, involves the observation of clinical signs and physiological parameters.13 Some of these signs are subject to reproducibility, while others suffer interference from external factors, and even from the subject being evaluated – in this case, infants. The intra-rater agreement was very good; however, the inter-rater agreement showed the limitations of video images of some clinical signs, such as multiple swallowing, chest wall indrawing, and wheezing.

Some limitations could be observed in this study. SCA tends to be influenced by the examiner's subjectivity and were partially controlled with the definition of variables and score of alterations, as well as with the agreement. It is noteworthy that the findings of this study include a small number of cases with more severe AVB, treated at a tertiary hospital. It was necessary to establish a large number of exclusion criteria, which limited the sample size.

Considering the results presented and discussed here, the feeding assessment appears to be important in the clinical evaluation of the medical team; it is suggested that a specific evaluation of deglutition performed by the speech therapist is requested, in cases with higher chances of aspiration. The creation of protocols for the management of feeding during AVB deserves careful discussion. Based on clinical examination by the speech therapist, alterations were observed in the oral (prolonged pauses) and pharyngeal (wheezing, coughing, and gagging) phases of swallowing. There was a significant increase in the respiratory rate between pre- and post-feeding moments, and almost half of the infants had tachypnea.

An association was observed between the score of swallowing disorders and the decrease in oxygen saturation. Infants whose caregivers reported feeding difficulties during hospitalization had a significantly greater number of alterations in the swallowing assessment. There was a very good intra-rater agreement for most items.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.