Research that focuses on the expressive–receptive language gap in individuals with Down syndrome has consistently found that receptive language skills are more advanced than expressive language skills. Although this research has been limited to children, the assumption has been made that the relationship between receptive and expressive language skills does not change over the lifespan. The current research focuses on the receptive–expressive language gap in adults with Down syndrome (DS). The first phase of the study used a survey to explore the perceived difficulty of receptive and expressive language tasks by adults with DS. Findings were that the adults perceive receptive language tasks (following instructions) to be more difficult than expressive language tasks (speaking to others at work). The second phase of the study was designed as a follow-up to the survey results to explore the receptive–expressive language gap in greater depth in ten adults with Down syndrome. Formal language testing, surveys and interviews were used. Formal testing indicated that the relationship between receptive and expressive language skills was more individualized in the adults. Survey and interview results indicated that participants perceived receptive skills to be more difficult than expressive skills in employment settings and daily living. Discussion considers reasons for the between subject variation and ramifications for IEP (Individualized Eduation Program) and transition planning. Conclusion is that the assumption cannot be made that the receptive–expressive language gap is the same at different ages and that there is a need to individually assess receptive and expressive language skills at all ages.

La investigación centrada en la brecha del lenguaje expresivo-receptivo en personas con síndrome de Down ha comprobado de modo consistente que las técnicas del lenguaje receptivo están más avanzadas que las del lenguaje expresivo. Aunque este estudio se ha limitado a los niños, se ha estimado que la relación entre las técnicas de los lenguajes receptivo y expresivo no varía a lo largo de la vida. La investigación actual se centra en la brecha del lenguaje receptivo-expresivo en adultos con Síndrome de Down (SD). La primera fase del estudio utilizó una encuesta para explorar la dificultad percibida de las tareas de los lenguajes receptivo y expresivo en adultos con SD. Los hallazgos concluyeron que los adultos perciben más dificultad en las tareas del lenguaje receptivo (seguimiento de instrucciones) que en las del lenguaje expresivo (hablar con los demás en el trabajo). La segunda fase del estudio se diseñó como un seguimiento de los resultados de la encuesta, para explorar en mayor profundidad la brecha del lenguaje receptivo-expresivo en diez adultos con Síndrome de Down. Se utilizaron pruebas de lenguaje formal, encuestas y entrevistas. Las pruebas formales indicaron que la relación entre las técnicas de los lenguajes receptivo y expresivo era más individualizada en los adultos. Los resultados de la encuesta y la entrevista indicaron que los participantes percibieron más dificultad en las técnicas receptivas que en las expresivas en los centros de trabajo y en la vida diaria. La discusión considera los motivos de la variación entre sujetos y las ramificaciones del PEI (Programa de educación individualizado) y de la planificación de la transición. La conclusión es que no puede conjeturarse que la brecha del lenguaje receptivo-expresivo es igual para las diferentes edades, y que existe una necesidad de evaluar individualmente las técnicas de los lenguajes receptivo y expresivo en todas las edades.

It has been widely documented in the research literature that children with Down syndrome (DS) comprehend more than they can say. Research using formal testing and clinical observation has consistently found that receptive language skills (e.g. comprehension, understanding, following instructions) are more advanced than expressive language skills (e.g. formulation and speaking).1–16 Miller10,12 found that more than 75 percent of his subjects demonstrated deficits in language production when compared to language comprehension and cognitive skills, and that the expressive language difficulties increased over time. This is known as the receptive–expressive language gap. The research literature has generally been limited to children, and has consistently documented that children with Down syndrome understand more than they can express. It has been assumed that the relationship between expressive and receptive language skills does not change as children develop into adults. The limited research literature on language in adolescents has generally focused on difficulties with expressive language and speech intelligibility, but has not compared receptive and expressive language skills.17–19 In recent discussions by the author with adults with Down syndrome, there has been anecdotal evidence that some adults perceive the receptive language demands at work as more difficult than the expressive communication demands. This is in direct contrast to the research and clinical findings in children and is worthy of further investigation.

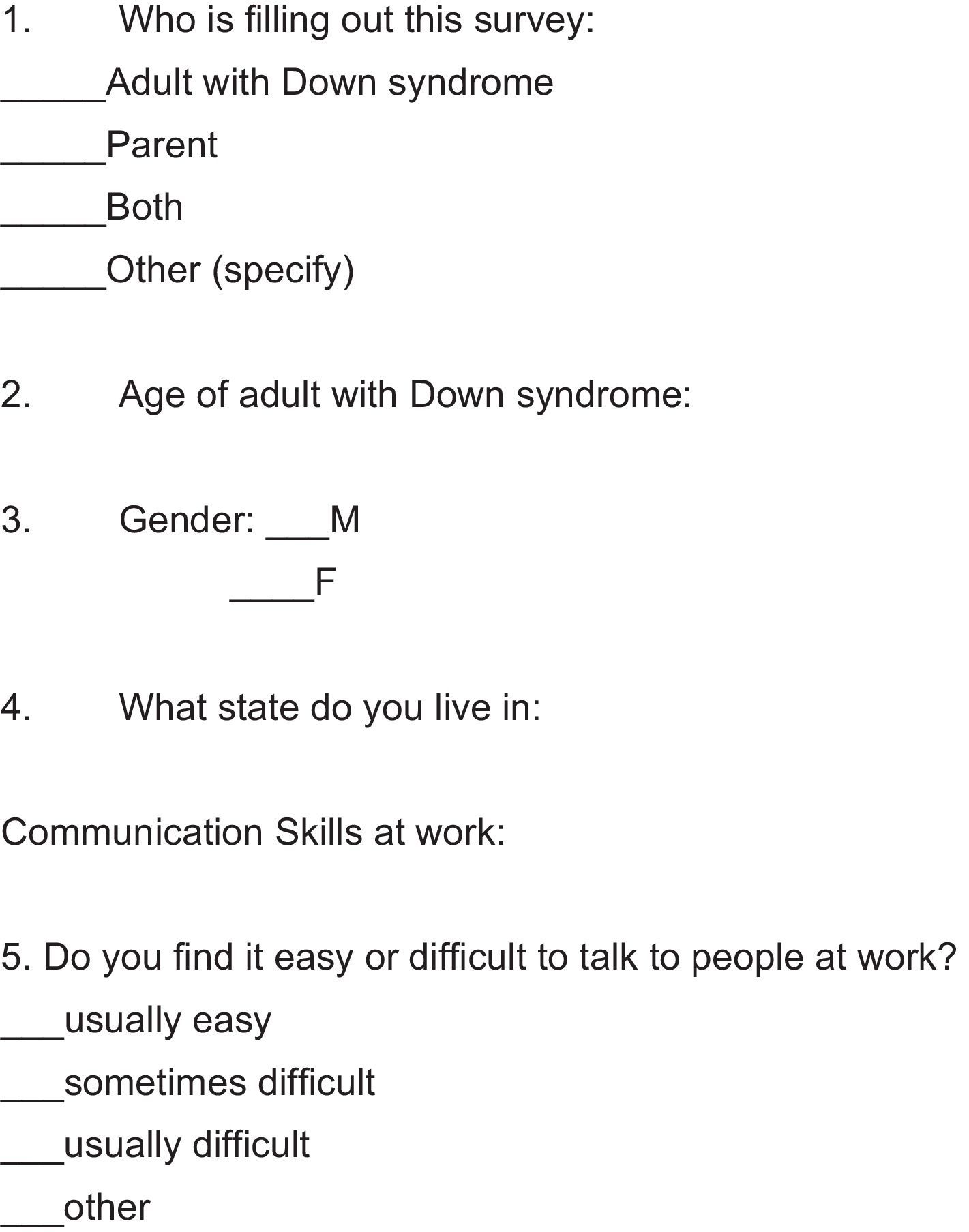

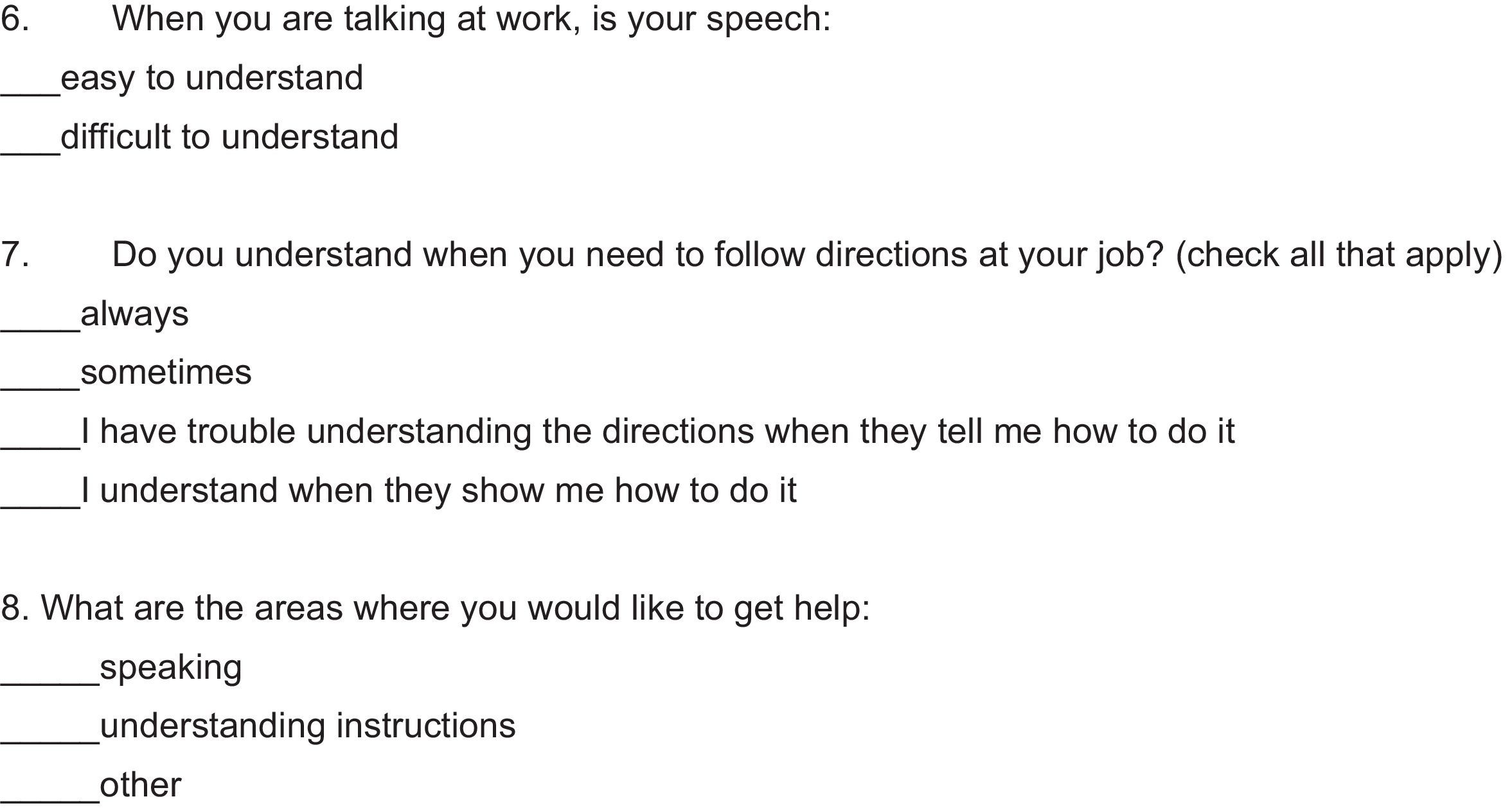

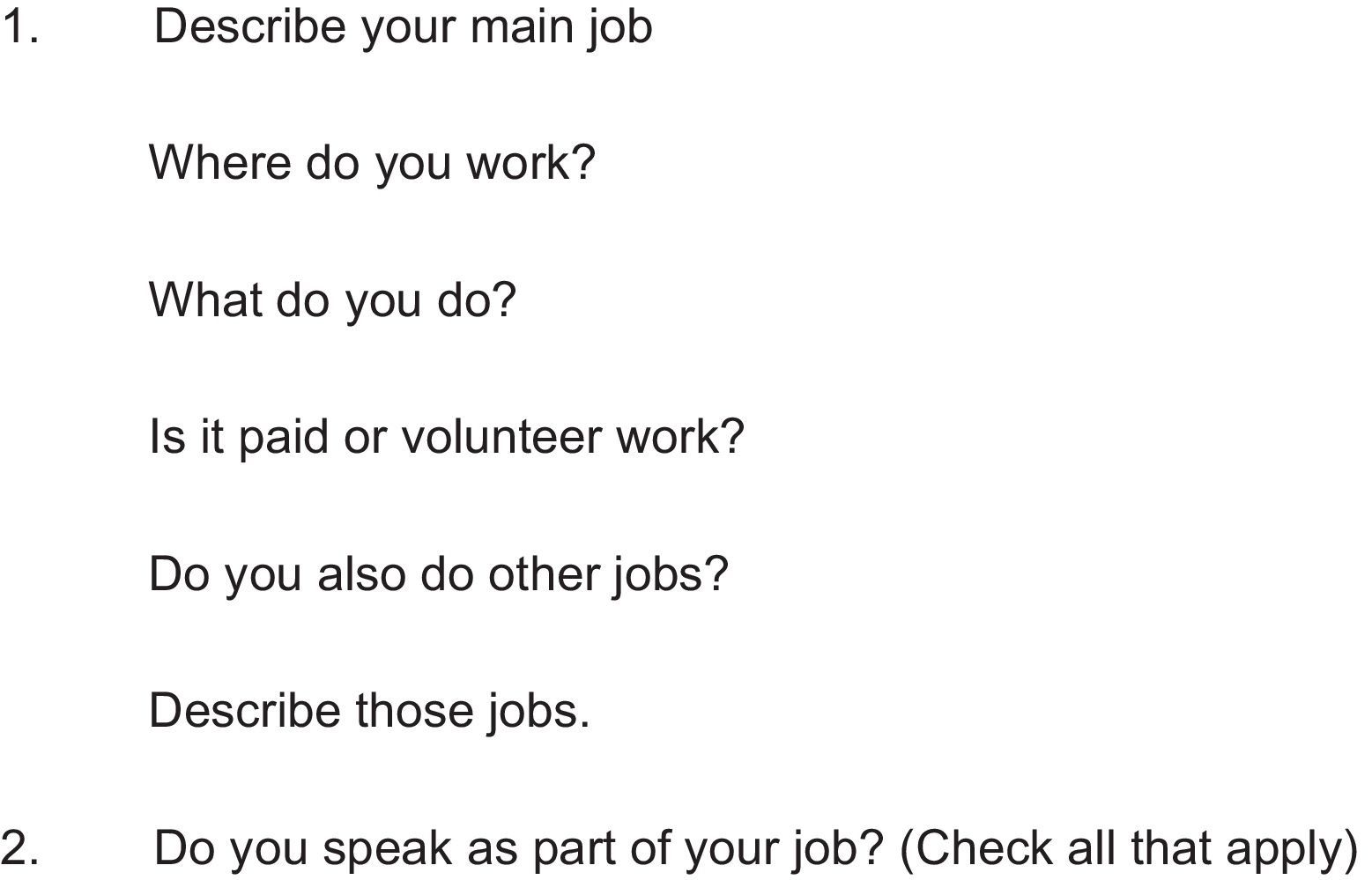

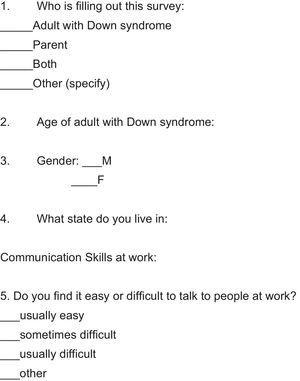

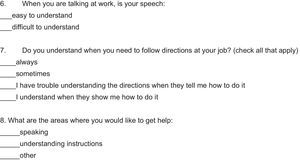

MethodTo begin to investigate the relationship between receptive and expressive language skills in adults, a survey that examined the perception of adults with Down syndrome relating to their difficulty with understanding language and speaking in workplace settings was developed. Survey questions relating to communication can be found in Appendix A. Participation was invited through postings on the message boards of the National Down syndrome Congress and the National Down Syndrome Society, and mailings through national parent support networks in the United States, Five hundred eleven survey responses were received. Respondents ranged in age from ages 18 years to 61 years. The majority of the respondents (72%) were in the 18–30 year age group. Surveys were received from 37 states. The gender of the respondents were 53.2% male and 46.8% female. The survey forms were completed by parents 78.8% of the time, 4.5% were completed by adults with Down syndrome on their own, 8.8% by adults with their parents, and 7.8% by others including siblings and support people. The survey results documented that the respondents perceived greater difficulty with receptive language skills, specifically comprehending and following instructions at work. In response to the results of phase one, a second phase of the study was designed to examine receptive and expressive language skills in ten adults in greater detail. The hypothesis was that the receptive and expressive language demands of the workplace are different from the demands of school and childhood, and also different from expressive and receptive skills probed in formal language testing. Measures used included a more in-depth survey, an individual interview about speech and language in the workplace, and formal language testing. Participation was requested through local parent group message boards. Since individual live interviews and formal individual testing were used, all participants were from the local Baltimore–Washington area.

Phase 2 of the study included 10 participants who met the following criteria:

- 1.

21–35 years of age

- 2.

Diagnosis of Down syndrome with the etiology of trisomy 21m

- 3.

Currently using speech as their communication system

- 4.

Currently working at a paid or volunteer job in the community (not in a sheltered or group workshop setting).

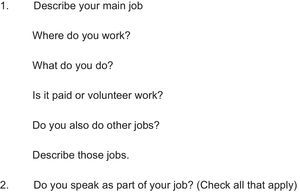

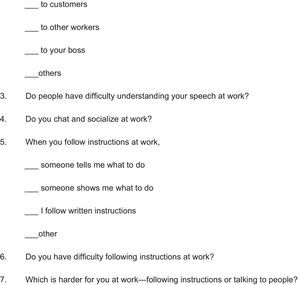

Each participant received an email survey to complete before the in-person session. A copy of the survey can be found in Appendix B. When the participant came in for the live session, there was more discussion about communication in the workplace. Questions were asked to follow up on the responses to the email survey. The participant's responses were audiotaped, and an MLU (mean length of utterance) was calculated based on their responses. Two judges (certified SLPs) and a graduate student SLP clinician rated the speech intelligibility of each participant on a 1–10 scale with 1 being completely unintelligible and 10 being completely intelligible. Interjudge reliability was 90%.

For the formal language assessment, each subject was tested with the Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test 4th edition (ROWPVT-4) and Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test 4th edition (EOWPVT- 4) to evaluate the individual's single word receptive and expressive vocabulary. The Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (ROWPVT-4) assesses receptive vocabulary by asking the examinee to match a word spoken by the examiner to a picture of an object, action, or concept. The examinee is given a field of four images and is asked to identify the picture that labels the spoken word said by the clinician. The Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOWPVT- 4) evaluates expressive vocabulary by requesting the examinee to label images of objects, actions, and concepts without any context. There are 190 items in each test; the items are presented in a developmental sequence according to level of difficulty beginning with the easier items or tasks. Two informal techniques, a written survey and an interview, were used to learn more about the receptive and expressive language demands at work. Based on conversations during the interview, MLU was calculated for each participant.

ResultsThe results of the survey in phase one indicated that adults with Down syndrome found following instructions at work to be more difficult than speaking/expressive language tasks at work. In response to question 1: Do you find it easy or difficult to talk to people at work? 53.3% responded usually easy, 28.3% responded sometimes difficult, 12.1% responded usually difficult and 6.3% responded other. Some of the difficulties cited, under other, were nonverbal/limited verbal output, shyness and other pragmatic issues, and decreased speech intelligibility. In response to question 2: When you are talking at work: 29.6% responded that their speech was easy to understand, 57.4% responded that their speech was sometimes difficult to understand and 13% responded that their speech was always difficult to understand. In response to question 3: Do you understand when you need to follow directions at your job, 30.3% reported that they always understand and 42.9% reported that they sometimes understand. Question 4 addressed how they were given instructions at work, with visual models or oral instructions and which worked better for them. At work, do people tell you or show you how to do a task? In response, 14.9% checked off I have trouble understanding the directions when they tell me how to do it and 37.2% checked off I understand when they show me how to do it. The final question asked the respondent to check off all speech and language skills you want help with. The results were as follows: Understanding instructions – 63.9%; Speaking – 52.8; Other – 25.6% Other included asking for help (3%), Learning new tasks (2%), Relationship/Social (3%), and Learning harder tasks – (2%).

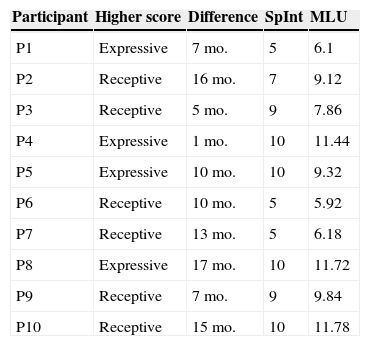

The results of the second study do not support the existence of a unidirectional receptive–expressive language gap in adults with Down syndrome. Six of the 10 participants (60%) had higher scores on the ROWPVT (receptive one word vocabulary skills) and 4 (40%) had higher scores on the EOWPVT (expressive one word vocabulary skills). The difference between the receptive and expressive test results for each participant ranged from 1 month to 17 months. Table 1 summarizes the formal test results.

Receptive–expressive language results.

| Participant | Higher score | Difference | SpInt | MLU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Expressive | 7 mo. | 5 | 6.1 |

| P2 | Receptive | 16 mo. | 7 | 9.12 |

| P3 | Receptive | 5 mo. | 9 | 7.86 |

| P4 | Expressive | 1 mo. | 10 | 11.44 |

| P5 | Expressive | 10 mo. | 10 | 9.32 |

| P6 | Receptive | 10 mo. | 5 | 5.92 |

| P7 | Receptive | 13 mo. | 5 | 6.18 |

| P8 | Expressive | 17 mo. | 10 | 11.72 |

| P9 | Receptive | 7 mo. | 9 | 9.84 |

| P10 | Receptive | 15 mo. | 10 | 11.78 |

How did participants perceive the level of difficulty of receptive and expressive tasks at work. Perceptions of the 10 participants as to relative difficulty are as follows:P1 Expressive is easier; uses social scripts; following complex verbal directions is most difficult at work. Expressive is easier; for receptive, asks the speaker to repeat if she doesn’t understand instructions. No difficulty with receptive or expressive at work; repetitive job; supervisor shows her how to do new tasks; does well with chatting and socializing. No difficulty with receptive or expressive at work; there is a written schedule to follow; social conversation. No difficulty with expressive; sometimes harder to remember and follow instructions at work. No difficulty with receptive or expressive; familiar people to interact with at work; repetitive job. Receptive is harder at work; sometimes has difficulty following instructions; likes to talk but sometimes people at work have difficulty understanding his speech. No difficulty with receptive or expressive, but prefers when supervisor shows him what to do, rather than telling him. Both receptive and expressive are easy for him; prefers when they show him what to do and provide demonstrations. Both receptive and expressive are easy; list of daily tasks are written in a book at work.

There was no direct correlation between the participants related to test score discrepancies and the perceptions of the adults on the relative difficulty of the two tasks. The nature of the job setting and tasks impacted the perception. For example, two participants who worked in preschool settings did not find following instructions difficult. In that setting, there is a definite routine and tasks such as setting up learning centers, story time or snack time which do not change from day to day. On the other hand, a young man who worked at Home Depot reported great difficulty with following directions. He worked in landscaping and since that area has little activity in the winter, he was often assigned to different supervisors in different divisions to assist them. All directions were given verbally and he was not provided with visual/written instructions or models.

DiscussionBased on an extensive body of research literature in children, it has been assumed that adults with DS also experience a receptive–expressive language gap, with receptive skills being more advanced. We also know from the literature that there are specific difficulties in children and adolescents with DS in following verbal instructions related to short-term memory difficulties that make it hard for them to remember and follow complex verbal instructions.20 In the school years, models and visual cues such as pictured or written instructions are used to help circumvent those difficulties. We need to reexamine the receptive and expressive language skills in adolescents and adults. Few adolescents and adults receive speech and language services, and speech and language services are rarely written into the educational transition plan to help adolescents transition from school to employment. If receptive language, specifically following complex verbal directions, presents difficulties in the workplace, that needs to be considered so that short term memory skills and following directions can be addressed in IEP planning during the school years and in the transition plan for the post-school years. The ability to follow complex directions is not a skill that is generally measured or considered when seeking employment opportunities for individuals with DS. There may be a need for modification of verbal instructions to include visual cues, diagrams, lists of sequences or models, but it is usually not explored. More often, the individual is placed in a lower level repetitive job such as bagging groceries where their skills will not be tested or challenged. Shining a light on the need to examine the receptive–expressive gap in adults with DS can have positive implications for job training and for job success.

In this study, the formal test scores (ROWPVT and EOWPVT) were compared with the perceptions of the participants regarding communication at work. All of the participants perceived expressive skills as equal to or easier than receptive skills, despite the fact that 6 out of 10 scored higher on receptive vocabulary on formal testing. It may be that expressive skills are perceived as easier at work because they are different skills (primarily social conversation skills) than are measured on the formal language tests. All of the participants indicated that they had no difficulty talking with co-workers, although P7 indicated that sometimes at work, people had difficulty understanding him. Many of our communication encounters, repeated throughout our work day, are social scripts. These skills have been documented as a strength for children with Down syndrome.21,22 In the school years, verbal instructions are often modified and visual assists and models are provided that help a child with Down syndrome follow directions and learn. If we know, through test results and interviews that following directions is difficult for an individual, this information can be applied to improve the preparation of adults for employment during the school years when they are transitioning to employment (ages 16–21 years). There may be a need to work on following complex verbal directions during the later school years and there may be a need for modification of verbal instructions on the job, to include visual cues, diagrams, and lists of sequences or demonstrations. Employers may assume that the adult workers with Down syndrome are choosing not to follow instructions, when in reality, those adults are having difficulty understanding the instructions, and do not know how to ask for clarification. We also know that social skills, conversational skills, and particularly social scripts are the primary expressive communication skills that adults with Down syndrome use at work. Many of our social encounters are repeated throughout our work day, e.g. saying hi or bye, and asking how some is feeling. These are practiced at school, at home and in the community. Because they are repeated and are rehearsed, they are known as scripts. Social conversational skills have been documented as a strength for children with Down syndrome.21,22 So, it is possible that in the workplace, the expressive language skill demands are in an area of strength for adults with Down syndrome. In the interviews, several participants said that they had no difficulty talking with co-workers but they got into trouble at work for talking too much and wasting time. Speech-language therapy can address staying on topic, being succinct, and asking for clarifications, all areas that are often difficult for children and adults with Down syndrome. Pediatricians can play an important role by bringing the need for speech-language pathology services to the attention of families, and referring them for appropriate services. The results of the current study document the need for individual assessment of the receptive–expressive gap in adolescents and adults with Down syndrome. Language intervention and visual supports can then focus specifically on the difficulties ion receptive and expressive language for that individual. Shining a light on the need to examine the receptive–expressive gap in adults with DS can have positive implications for education, job training and for job success.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflict of interest to declare.

This research was supported by the Global Down Syndrome Foundation and the Loyola University Maryland Summer Faculty Development Grant. Thanks to Lora Hellman, Katie Azzara, Laurier Kinney, and Tara Lopez for their assistance with the project.

There is currently no information available on employment and unemployment status for adults with Down syndrome. The purpose of this survey is to begin to collect that information. So, it is important for you to fill out and return this survey whether you are working in paid or volunteer jobs, not currently working, or are in a training program to prepare you for jobs. The survey is designed for parents/caregivers and their adult children with Down syndrome, ages 18–50 years old. Please post the link on listservers and in your newsletters. Everyone's response is important. Thank you for completing the survey.