Septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint is a rare entity: only 30 cases have been reported in the literature since 1985. We present the case of a 53-year-old diabetic male, with septic arthritis of one acromioclavicular joint due to Streptococcus agalactiae. Current condition characterised by neck pain, limited movement of the right shoulder; hyperthermia, hyperaemia and increased volume in the acromioclavicular joint. Upon physical examination, increased volume was found from the proximal third of the deltoid to the middle third of the clavicle, pain on palpation, localised hyperthermia, limited range of motion. X-ray with enlargement of soft tissues, presence of subcutaneous gas and increased space in the acromioclavicular joint compared with the contralateral. Ceftriaxone and Clindamycin were administered at therapeutic doses and an acromioclavicular arthrotomy was performed, obtaining 10ml of purulent material from the sub-deltoid and 2ml from the joint. Five days later, Streptococcus agalactiae was reported. Clinical improvement was observed and it was decided to discharge the patient.

La artritis séptica acromioclavicular (ASAC) es una entidad poco frecuente, desde 1985 se han reportado 30 casos en la literatura. Se presenta el caso de un paciente masculino, diabético, de 53 años, con ASAC monoarticular por Streptococcus agalactie. Padecimiento actual caracterizado por dolor en cuello, limitación al movimiento de hombro derecho, hipertermia, hiperemia y aumento de volumen en articulación acromioclavicular. A la exploración física, con aumento de volumen en tercio proximal de deltoides hasta tercio medio de clavícula, dolor a la palpación, hipertermia localizada, arcos de movilidad limitados. Rx con aumento de partes blandas, presencia de gas subcutáneo y aumento de espacio articular acromioclavicular en comparación con la contralateral. Se administra Ceftriaxona y Clindamicina a dosis terapéuticas y se realiza artrotomia acromioclavicular derecha, se obtiene 10cc de material purulento subdeltoideo y 2cc articular. Se reporta al 5° día Streptococcus agalactie. Presenta mejoría clínica y se decide egreso.

Septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint is a rare entity; 30 cases have been reported in the literature since 1985.1

The most frequent etiological agent at any age is Staphylococcus aureus in 75% of cases, followed by gram-negative in 20% of cases. Chronic presentation is usually due to microbacteria and filamentous fungi.1,2

Once the germ is found in the synovial membrane, it begins to reproduce and various virulence factors are produced such as extracellular toxins, enzymes, adhesins, proteins with bacterial cell walls, which trigger a flood of inflammation through T cells, B cells and macrophages. As a consequence, pro-inflammatory molecules including TNF-a, IL-B and IL-6, immunomodulatory and inflammatory cytokines are produced by monocytes, macrophages and synovial fibroblasts so that in a period of 24–48h, intra-articular effusion occurs with a polymorphonuclear leucocyte count of up to 50,000 per cubic millimetre, glucose reduction and an increase in proteins in the synovial fluid.3,4

Commonly affected joints are the knee (50%), hip (20%), shoulder (8%), ankle (7%), wrist (7%); Martinez-Morillo et al., reported a series of 101 cases of which 6% affected the acromioclavicular joint.2,5,6

The incidence of septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint is 2–10/100,000 in the general population; if the patient has an articular prosthesis, the incidence increases to 30–60/100,000, ranging in age from 17 to 79 with an average age of 54 years and is more prevalent in males 5:1.6–9

Treatment is medical-surgical and is considered urgent due to the potential for serious consequences. Its natural evolution leads to the destruction of the articular cartilage and the adjacent bone.

Up until now, only 30 cases of septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint have been reported.10 The purpose of this document is to present the case of a patient with septic arthritis of one acromioclavicular joint caused by Streptococcus agalactiae.

Case reportMale, 53 years of age, type 2 diabetic, condition evolving for 15 days, characterised by neck pain, limited shoulder movement, hyperthermia, hyperaemia and increased volume in the right acromioclavicular joint. Symptom management, presenting partial improvement. Evolution with an increase in symptomatology and fever.

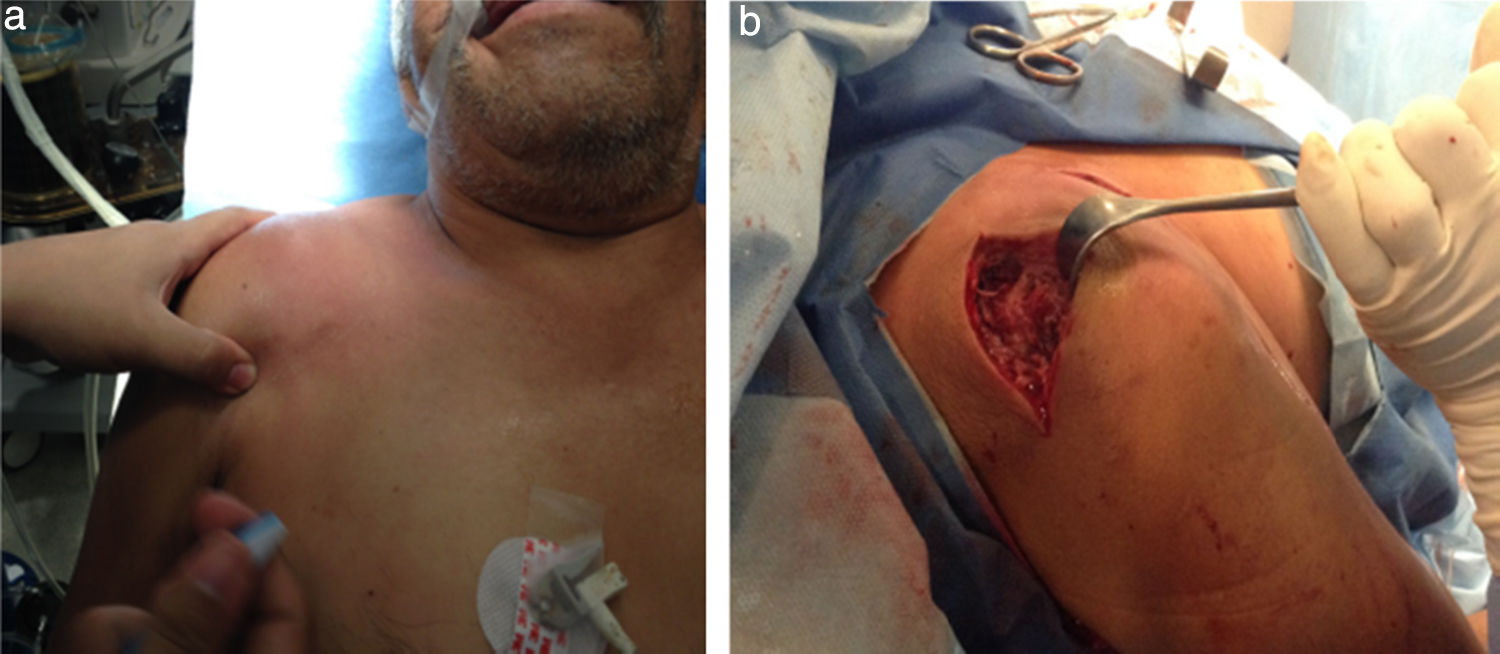

The physical examination shows shoulder asymmetry with an increase in volume from the deltoid region to the middle third of the right clavicle (Fig. 1a), hyperthermia and pain on palpation 10/10 VAS in the acromioclavicular joint, limited range of motion in the joint, secondary to pain and without distal neurovascular compromise.

Lab tests: leukocytes: 16,800mm3, neutrophils: 75.50%, glucose: 341mg/dl.

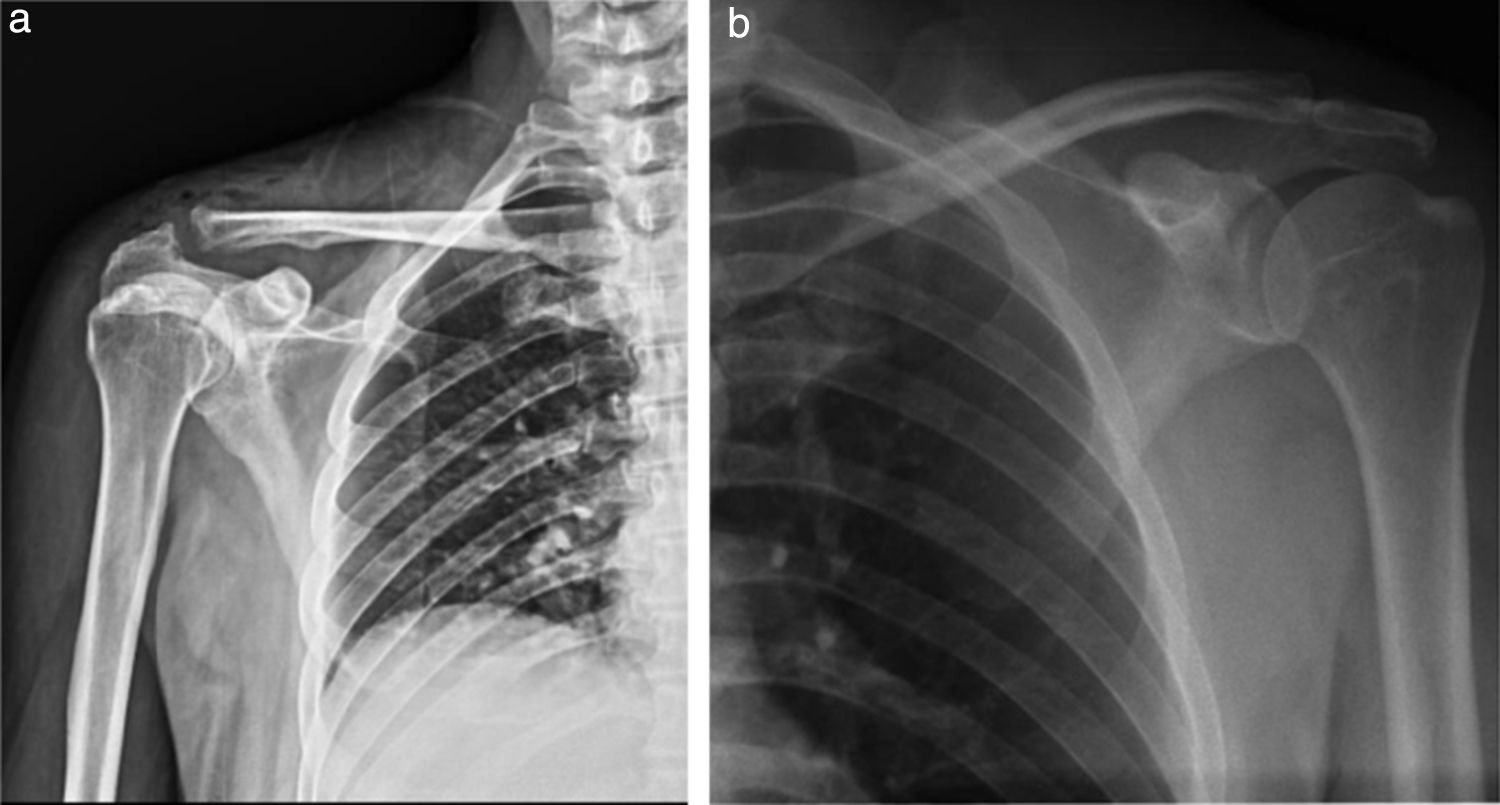

Comparative AP radiography of shoulder (19/09/2014) (Fig. 2a and b): Right: with enlargement of soft tissue, presence of subcutaneous gas and increase in the acromioclavicular joint space (9mm) compared to the contralateral. Left: Acromioclavicular space of 1.41mm. No bone lesion data.

Comparative shoulder X-rays: (a) Right shoulder X-ray: volume increase in soft tissues, with radiolucent images compatible with subcutaneous emphysema; irregular acromioclavicular bone edges, right acromioclavicular joint 9.61mm. (b) Left shoulder X-ray: Acromioclavicular space 1.41mm without any bone injury data.

Intravenous antibiotic therapy initiated with 1g of Ceftriaxone every 12h and 600mg of clindamycin every 8h. Arthrotomy on the right acromioclavicular joint, surgical lavage and debridement were performed (Fig. 1b), obtaining 10ml of subdeltoid purulent and 2mm of articular exudate.

Culture report: Streptococcus agalactie.

The same antibiotic regimen was continued for proper evolution until completion at the end of the 10 days. Evolution with improvement and decrease in leucocyte numbers (16,800mm3→9300mm3) and ESR (31mm3/h→10mm3/h). Discharged with oral antibiotic (500mg ciprofloxacin orally every 8h and 300mg clindamycin every 8h) for 4 weeks.

Follow-up 2 weeks after surgery, asymptomatic. The last control was at 9 months where the X-ray showed a lytic acromioclavicular space of 11mm and full range of motion in the right shoulder (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThis is a rare pathology given the limited space and characteristics of the joint, and may even be underdiagnosed because it is not easy to distinguish a septic glenohumeral disorder from a simple physical examination.2,3,8,11,12

In addition, it must be differentiated from traumatic synovitis, abscesses, acute rheumatic fever, joint infection due to microbacteria, cellulitis, acute osteomyelitis and haemophilia.3,9,13

Septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint tends to appear in immunocompromised patients, either infected with HIV, rheumatoid arthritis, renal insufficiency, multiple myeloma, chronic steroid use, hepatic cirrhosis2,8; as well as a history of venipuncture, local trauma, articular puncture, prior shoulder surgery, septic arthritis in another joint, periprosthetic infections and ulcers on diabetic feet.8,9,14

The patient being studied had a history of chronic evolution as an insulin-dependent diabetic, who did not adhere well to treatment and did not use glucose-lowering drugs for 1 week prior to his admission. He also presented with plantar infections 6 and 12 months prior.

It is described that in the absence of trauma and articular manipulation, septic arthritis must be considered a consequence of haematogenous dissemination,8,9 as is likely in the case of our patient.

Patients present initially with general symptoms such as general malaise, diffuse pain, hyperthermia; after a few days, the focus is on increased volume, local oedema that limits shoulder and even neck movement, pain upon superficial palpation of the anterior shoulder, O’Brien manoeuvre or active compression of the positive acromioclavicular joint, with evolution ranging between less than 24h and up to 12 days.

The vast majority were previously treated with analgesics and anti-inflammatories, as in this case, leading to the delay in diagnosis and treatment 15 days after onset.

Chronic cases are attributed to microbacteria and can take up to a year to diagnose.13

Image studies are very useful for diagnosis.

A simple X-ray of the shoulder does not usually reveal bone changes in the initial stages,6,9,12 however, it is an easy, inexpensive, and quick study that does not merit patient preparation, is not user-dependent and provides a lot of data, both positive and negative, as in this case, where upon admittance, he already presented with changes that were very suggestive of the pathology and vital for regulating treatment.

Ultrasound is a tool for the early diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint,12 it can detect an increase in echogenicity, distension of the joint cavity, bone irregularity, as well as guiding punctures, similarly, septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint can be ruled out if the joint space is less than 3mm.15,16

Magnetic resonance imaging MRI) can detect septic joint changes in the first 24h of onset,8 changes compatible with oedema, joint effusion, thickening of the cartilage and, as with ultrasound, septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint can be ruled out if the joint space is less than 3mm in a coronal cut.12

A firm suspicion, knowledge of the pathology and a focused physical examination are vital for diagnosing septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint2 and tests such as MRI and ultrasound may not always be available.3

Antibiotic treatment should initially be empirical and focus on the most common causal agent (S. aureus), and subsequently be adapted according to the cultivated agent; similarly, treatment provided should be directed at improving the general conditions with emphasis on the underlying pathologies and as a priority factor, drainage of the affected joint should be performed.

In the current case, the isolated agent is rare, Group B Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS), which is a commensal bacterium that is part of the intestinal and vaginal tract in 15–30% of healthy adults, but is one of the most significant pathogens in newborns. Endogenous factors such as diabetes alter the normal composition of the intestinal microbiota; these factors can partly explain why GBS is a significant cause of infection in soft tissues and the urinary tract, of sepsis and arthritis in patients with chronic disorders.4

In the published literature, we find only the case of a patient with bilateral septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joints, septic arthritis in the left hip and right knee with a history of CRI, skin lesion and abscess, treated intravenously with Penicillin G Sodium, oral amoxicillin and surgical debridement.6

Kyu Cheol Noh et al., comment that septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint can be treated conservatively if fever and pain improve with the administration of antibiotics, and report that surgical treatment should be used as an option in the event of ineffective antibiotic therapy, persistent fever, pain, and changes in bone erosion as well as radiographic osteomyelitis.3

We consider that septic arthritis is an orthopaedic surgical emergency, and should be treated as such. The proteolytic enzymes of the leukocytes are released in the joint, which leads to the destruction of cartilage and irreversible joint damage in 48h.3

The small size of the acromioclavicular joint is associated with a high risk of local spreading and more rapid destruction of the joint, as well as the potential danger of subsequent infection of the glenohumeral joint; given that it commonly presents in immunocompromised patients, an early diagnosis should be made and surgical treatment provided immediately.2,12

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.