Hypercalcaemia is a relatively common clinical finding, and its aetiology should be analysed in order to guide treatment.

Case report56-year-old male presenting with hypercalcaemia, lumbar pain and osteolytic lesions in lumbar vertebrae, with large B-cell lymphoma subsequently confirmed by histology and immunohistochemistry.

DiscussionCommon causes are primary hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcaemia associated with chronic kidney disease and paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia (secondary to malignancy). Less common causes are granulomatous diseases, lymphoma and vitamin D toxicity, all associated with vitamin D metabolism, and thyrotoxicosis associated with lithium or thiazide diuretic consumption.

ConclusionOur patient presents with malignant hypercalcaemia, probably secondary to extra-renal conversion of 25(OH)D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, which represents <1% of cases.

Hipercalcemia es un hallazgo clínico relativamente común, deberá analizarse la etiología de la misma para normar conducta terapéutica.

Caso clínicoSe presenta a masculino de 56 años de edad que debuta con hipercalcemia, lumbalgia y lesiones osteolíticas en columna vertebral lumbar, al que posteriormente se le confirma linfoma b de células grandes mediante histología e inmunohistoquímica.

DiscusiónLas principales causas son Hiperparatiroidismo primario, hipercalcemia asociada a enfermedad renal crónica e hipercalcemia paraneoplásica (secundaria a malignidad). Causas menos comunes son enfermedades granulomatosas, linfoma e intoxicación por Vitamina D, todas estas asociadas con el metabolismo de la Vitamina D; tirotoxicosis, asociada al consumo de litio o diuréticos tiazídicos.

ConclusiónNuestro paciente debuta con hipercalcemia maligna, probablemente secundaria a la conversión extrarrenal de 25(OH)D a 1,25-dihidroxivitamina D, que representa <1% de los casos.

Hypercalcaemia is a relatively common clinical finding and its importance lies in its large variety of origins. The main causes are primary hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcaemia associated with chronic kidney disease and paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia (secondary to malignancy). Less common causes are granulomatous diseases, lymphoma and Vitamin D toxicity, all associated with vitamin D metabolism, and thyrotoxicosis, associated with lithium or thiazide diuretic consumption.1

Case report56-year old male. From the State of Mexico. Has worked in a bodywork and paint shop for 28 years. Smoked for 4 years, 7 cigarettes per day, smoking index 1.4packs/year. Denies allergies, surgery, trauma and transfusions. Negative for exposure to tuberculosis. Negative for alcohol and substance abuse. Sexually active from the age of 16, 3 sexual partners, indistinct use of condom. No prior hospitalisations.

Onset 6 months before admission with abdominal pain located in mesogastrium and hypogastrium, subsequently irradiated to lumbar region, intermittent, diagnosed outside hospital as irritable bowel syndrome and treated with multiple regimens. Non-recorded fever predominantly in morning and night, no weight loss. Two months after onset of symptoms, dysuria, reduced micturition, increased frequency of urination and post-urination dripping. At the same time, disseminated dermatosis affecting the 4 limbs and front of abdomen, characterised by petechiae, lasting for 4 days, which resolved together with the aforementioned fever. Determination of prostate antigen in serum and a prostate ultrasound were ordered, finding values of 1ng/ml, enlarged prostate gland, smooth walls and no tumours.

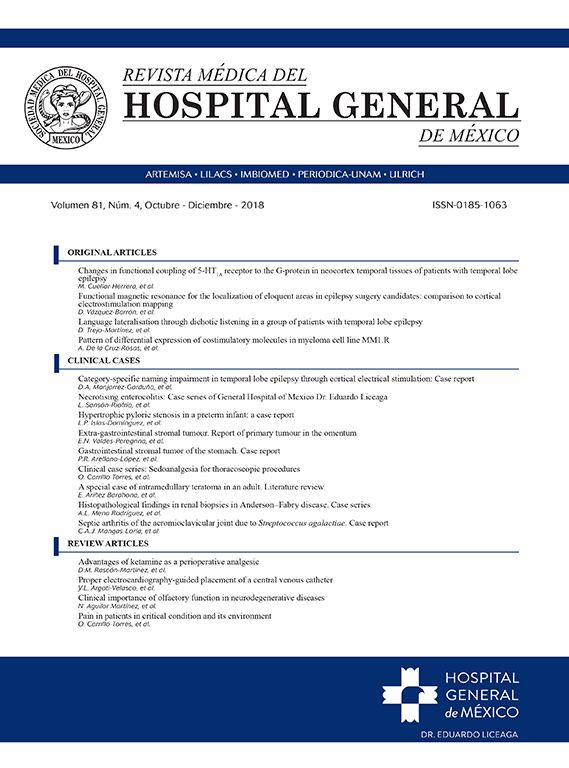

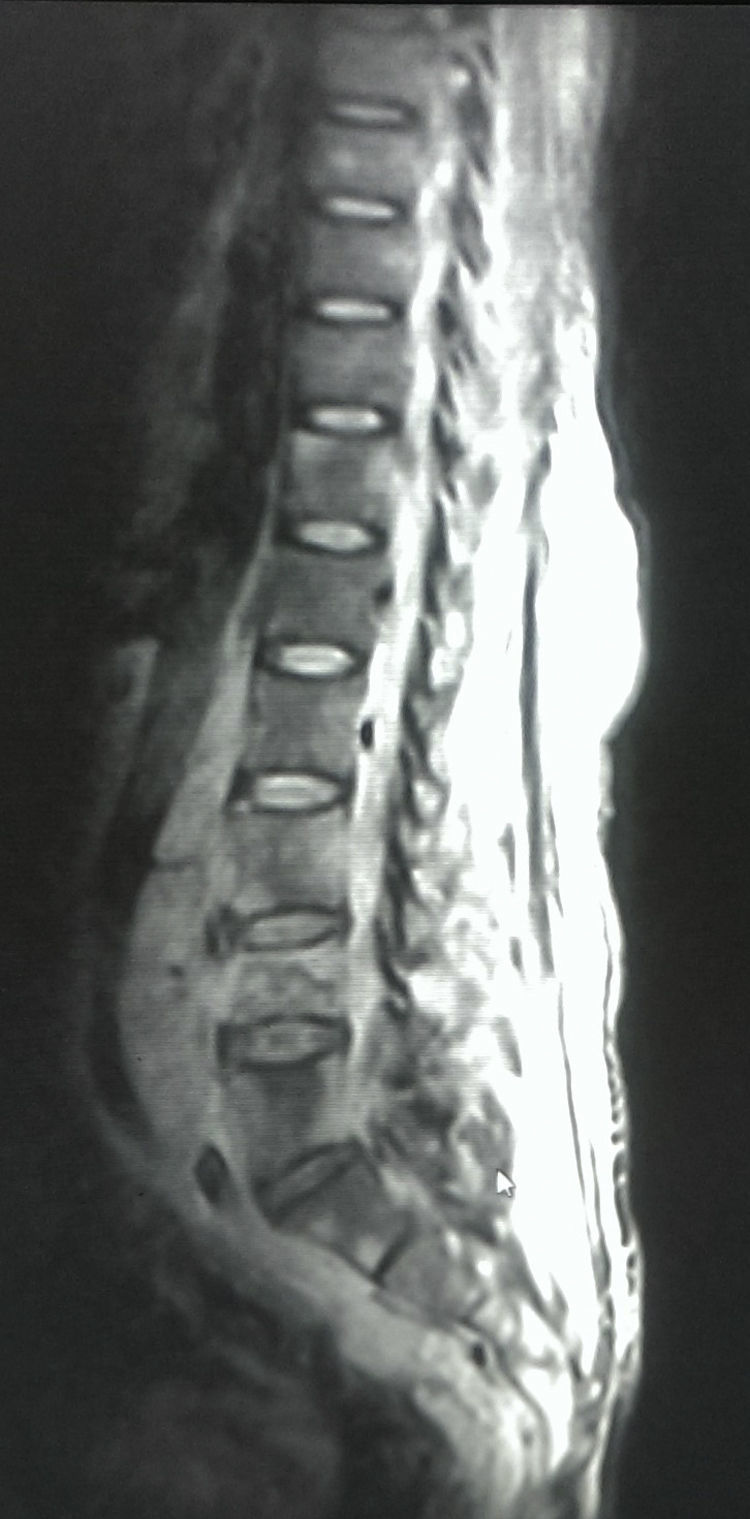

Two weeks prior to admission, back pain increased in intensity with the addition of pain in right leg, which limits movement, so he visited Neurosurgery as an outpatient. An analgesic regimen with NSAIDs and gabapentin was initiated, with partial improvement, and a spinal MRI was ordered.

Back and leg pain increased again, so he decided to go to the ER, where oedema of the affected limb, erythema in the same area and pain upon palpation was found. It was decided to admit him with probable deep vein thrombosis. Uncompromised capillary fill and sensitivity. Non-painful, bilateral scrotal oedema. Blood test at admission: thrombocytopenia 107,000, acute kidney injury with creatinine 2.5 and urea 83.5, hyperuricaemia 13.3, ALT 114, AST 131, DHL 863, Sodium 140, potassium 3.3, chlorine 95, hypercalcaemia 12.8, phosphorous 6.4, magnesium 2.3. Evaluation requested from Angiology, which ordered venous Doppler ultrasound. Admitted to the Internal Medicine Department to continue management and diagnosis, with a working diagnosis of malignant hypercalcaemia.

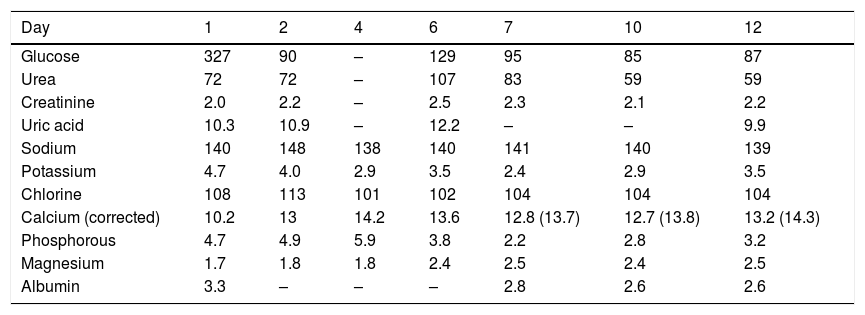

At admission to Internal Medicine, simple X-rays of the spine in anteroposterior and lateral positions showed lytic lesions in the L4–L5 vertebrae. Management of hypercalcaemia started with hyper-hydration in the ER. Given the lack of response, a loop diuretic and dexamethasone were administered, also with no response. The calcium levels are shown in Table 1, together with their progression. Electrolytic imbalance and hypercalcaemia are particularly noteworthy, despite the aforementioned therapies. Also significant was the patient's renal failure since admission.

Lab test results.

| Day | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 327 | 90 | – | 129 | 95 | 85 | 87 |

| Urea | 72 | 72 | – | 107 | 83 | 59 | 59 |

| Creatinine | 2.0 | 2.2 | – | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Uric acid | 10.3 | 10.9 | – | 12.2 | – | – | 9.9 |

| Sodium | 140 | 148 | 138 | 140 | 141 | 140 | 139 |

| Potassium | 4.7 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.5 |

| Chlorine | 108 | 113 | 101 | 102 | 104 | 104 | 104 |

| Calcium (corrected) | 10.2 | 13 | 14.2 | 13.6 | 12.8 (13.7) | 12.7 (13.8) | 13.2 (14.3) |

| Phosphorous | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| Magnesium | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| Albumin | 3.3 | – | – | – | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

The venous Doppler ultrasound of the right popliteal region showed deep vein thrombosis in the segment, so anticoagulation was started with low molecular weight heparin.

The spinal MRI scheduled prior to hospitalisation was performed, showing an apparently dependent lesion of both psoas, predominantly affecting the right side, involving the iliac psoas and right posterior spinal musculature, invasion of the spine through neural foramens L2–S1, wrapping around vascular structures of the aorta and inferior vena cava, right distal ureter with proximal dilation, and proximal dilation of the ipsilateral renal pelvis, suggesting a highly malignant tumour (Figs. 1–3).

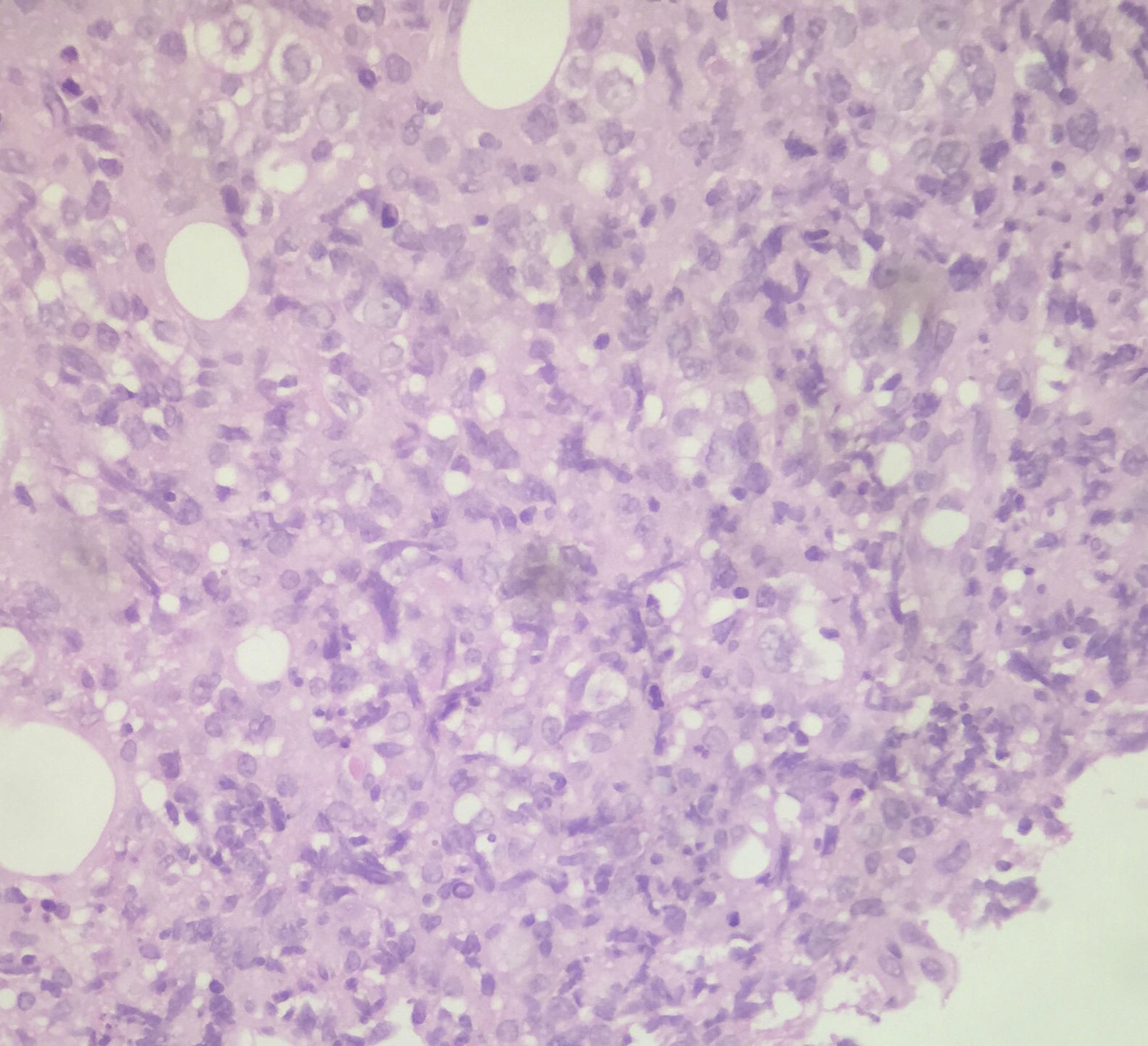

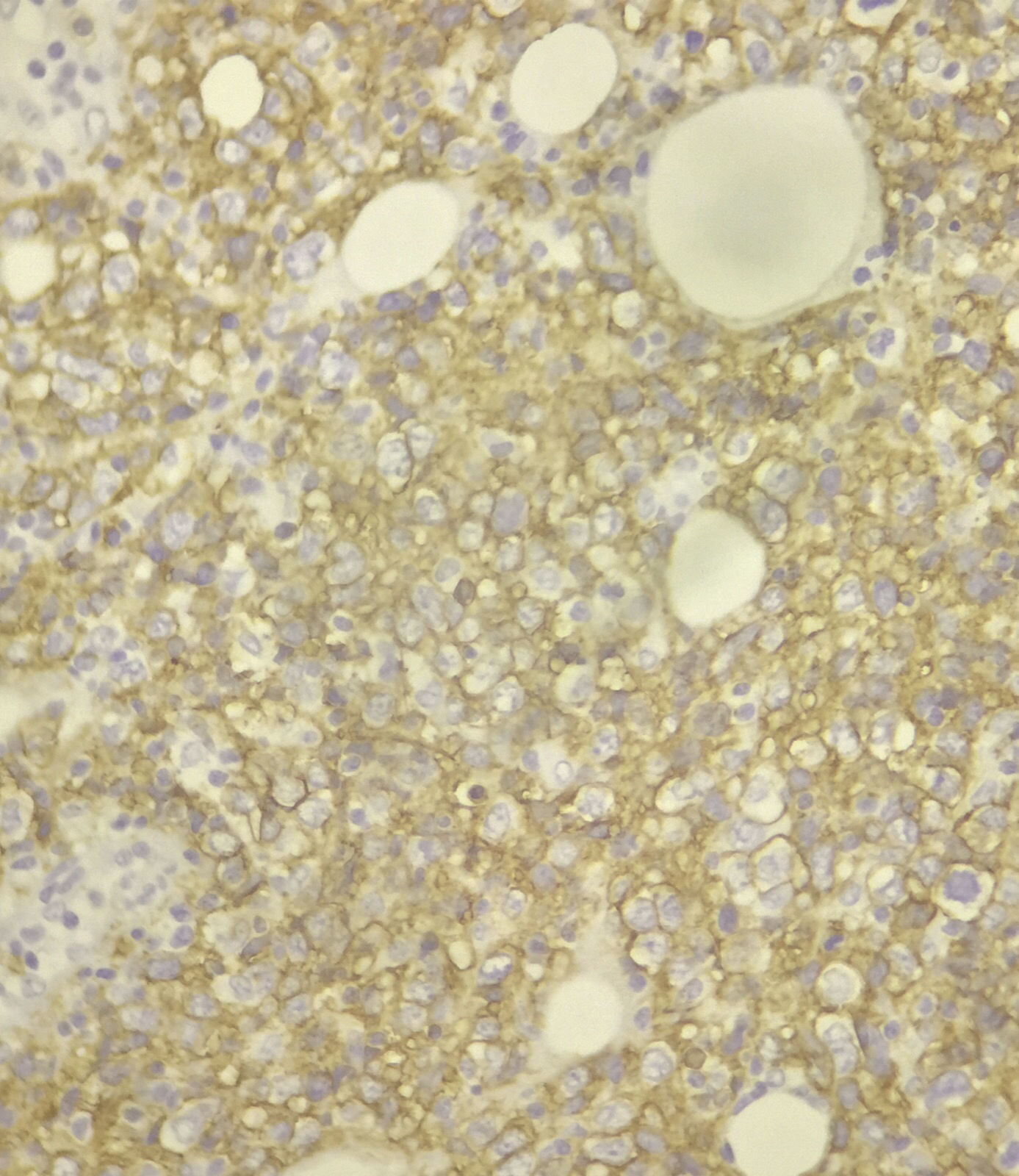

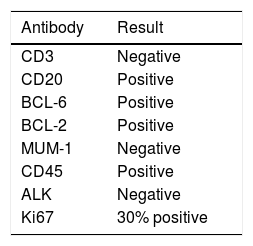

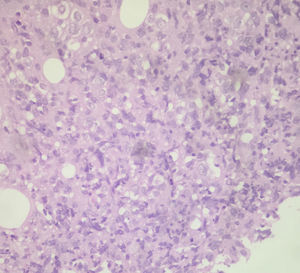

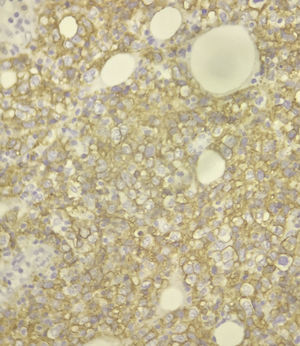

An ultrasound-guided tumour biopsy was ordered. The biopsy revealed “Large B-cell lymphoma with germinal centre immunophenotype, with 30% proliferative index”. The immunohistochemistry is shown in Table 2, Figs. 4 and 5:

The association of osteolytic lesions with lymphoma is found in 5–15% of cases, and hypercalcaemia and lymphoma in 10%. However, it is extremely rare for them to be the initial symptom of lymphoma (approximately 2%),2,3 hence the need to report such cases. The physiopathology is not fully known, although it is known that osteoclast activators such as MIP-1α, produced by tumour cells, are involved. These symptoms, however, can also be caused by other haematological diseases such as acute leukaemia (lymphoid and myeloid) and B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, etc.4,5

On a molecular level, the peptide related to the parathyroid hormone (PTHrP), inflammatory macrophage proteins 1α and 1β and calcitriol, have been related to lytic lesions and hypercalcaemia in lymphoma,6 giving these patients a poor prognosis.7

The importance of the treatment of malignant hypercalcaemia lies in the damage caused to the kidneys, the onset of which is a reduced response to the antidiuretic hormone, initially presented as inability to concentrate urine. The renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate subsequently diminish due to severe calcium-induced vasoconstriction.1

In a review of the national literature, there is a single case of a 15-year-old patient with primary pre-B cell bone marrow lymphoma who, during the progression of his disease, presented hypercalcaemia and osteolytic lesions. He received the necessary treatment and achieved disease remission.3 Internationally, there is only one report of a 58-year-old woman with similar onset, with hypercalcaemia and osteolytic lesions. She was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and was treated with a good outcome.8 We therefore highlight the importance of early diagnosis in order to start treatment regimens and improve the patient's quality of life and prognosis.

Ethical disclosureProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.