Abdominal aortic aneurysms have a varied aetiology, and the main causes include cigarette smoking and atherosclerosis, mainly affecting men in their seventh decade of life. It is complex to treat, with high rates of morbidity and mortality which have been reduced with minimally invasive techniques.

Case report73-year old female seen in the emergency room for lumbar pain lasting one week, she was later diagnosed with an aneurysm of the infrarenal aorta, which was treated with endovascular techniques.

DiscussionThe attending physician should accurately evaluate the treatment type. Endovascular repair shows lower mortality and morbidity in the short term, which is suitable for treating elderly patients.

El aneurisma de aorta abdominal es una patología de variable etiología, dentro de las causas más importantes el tabaquismo y la aterosclerosis, afecta principalmente al sexo masculino en la séptima década de la vida. Su tratamiento es complejo, con altas tasas de morbilidad y mortalidad, que se han reducido con técnicas de mínima invasión.

Caso clínicoFemenino de 73 años que acuda a urgencias por dolor lumbar de una semana de evolución, a quién se la diagnostica un aneurisma de aorta infrarrenal, resolviéndose con tratamiento endovascular.

DiscusiónSe debe evaluar el tipo de tratamiento a elegir, la reparación endovascular muestra menor mortalidad y a corto plazo y disminuye la morbilidad perioperatoria, beneficiando principalmente a pacientes de edad avanzada.

Aneurysms are defined as a focal dilation of an artery. Aortic aneurysms are defined as a 1.5-fold increase in the normal diameter at the level of the renal arteries.1 They are a degenerative process in a segment of the aortic wall, varying in length. This condition affects 1.5–2% of the general adult population, and increases to 6–7% among those over 60 years old.2,3

The most important risk factors for developing it are tobacco use, followed by high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, and being male.4,5 The prevalence in the United States is 55.00 new aneurysms per year, of which 17% are detected due to rupture. The average age is 67 years; 10–15% of patients die and only 10% survive the acute phase; 90% die within 10 weeks if it is not treated.6

A declaration by the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and the Society for Vascular Surgery estimates the annual risk of rupture according to the diameter of the sack: under 40mm in diameter – 0%; 40–49mm in diameter – 0.5–5%; 50–59mm in diameter – 3–15%; 60–69mm in diameter – 10–20%; 70–79mm in diameter – 20–40%; 80mm in diameter of larger – 30–50%.7

The most pronounced histological characteristic of AAA is the destruction of the tunica media and intima. Excessive proteolytic enzyme activity (especially metalloproteinases 2 and 9) in the aorta wall causes deterioration in the elastin and collagen protein matrix structure. There is also an increase in the migration of smooth muscle cells related to the overproduction of metalloproteinases, which leads to remodelling and disruption of the tunica media, which in turn causes the abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) to form and expand.8 There is also an aetiology related to Marfan and Ehlers–Danlos syndromes, and inflammatory aneurysms of infectious origin.

Endovascular techniques have revolutionised the treatment of both thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Initially their use was limited to a group of patients with certain clinical and anatomical characteristics, but over the years many of the limitations of the original systems have been overcome, with designs emerging that expand patient eligibility and provide a wider safety margin when placed. The first endoprosthesis inserted in humans by Dr. Parodi in 1990 had a rigid delivery system that was 27 Fr in diameter, requiring the access vessels to be dissected.

There is a large number of devices to choose from on the market. This is why it is essential to analyse the patient's individual characteristics to make an appropriate choice for the procedure, whether open or endovascular surgery, and to choose the most appropriate type of endoprosthesis for the AAA morphology.

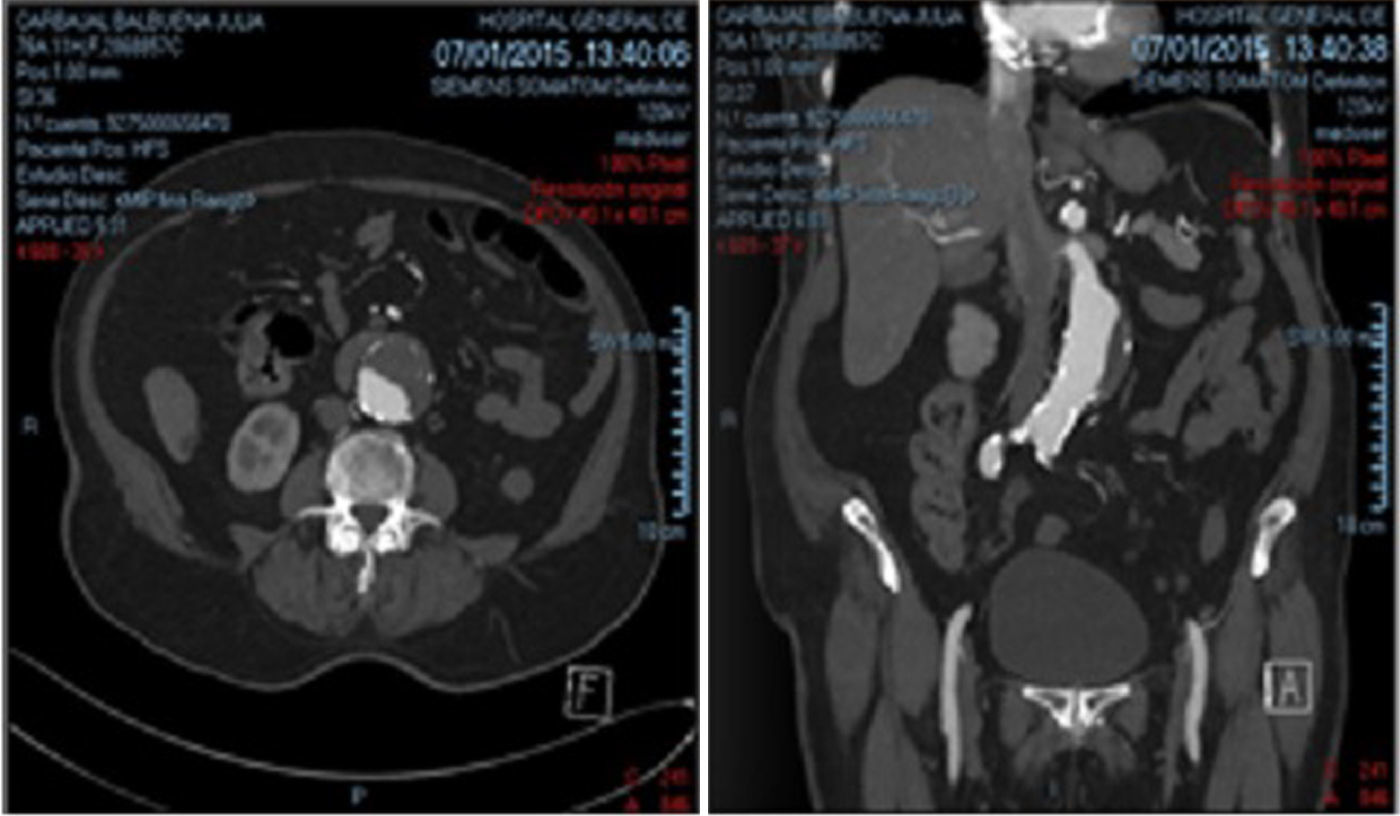

Case report73-year old female patient who came to the Emergency Room, referred by a satellite clinic with infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm and back pain lasting one week. Using CT angiography, an aneurysm with a diameter greater than 48mm was observed. The suprarenal aorta diameter was 19mm, the infrarenal aorta diameter 22mm, neck 24mm, length of the sack 109mm, anterior mural thrombus with an irregular lumen wall near the neck, and tortuous common and external iliac arteries, common femoral artery 5mm (access vessel) (Fig. 1).

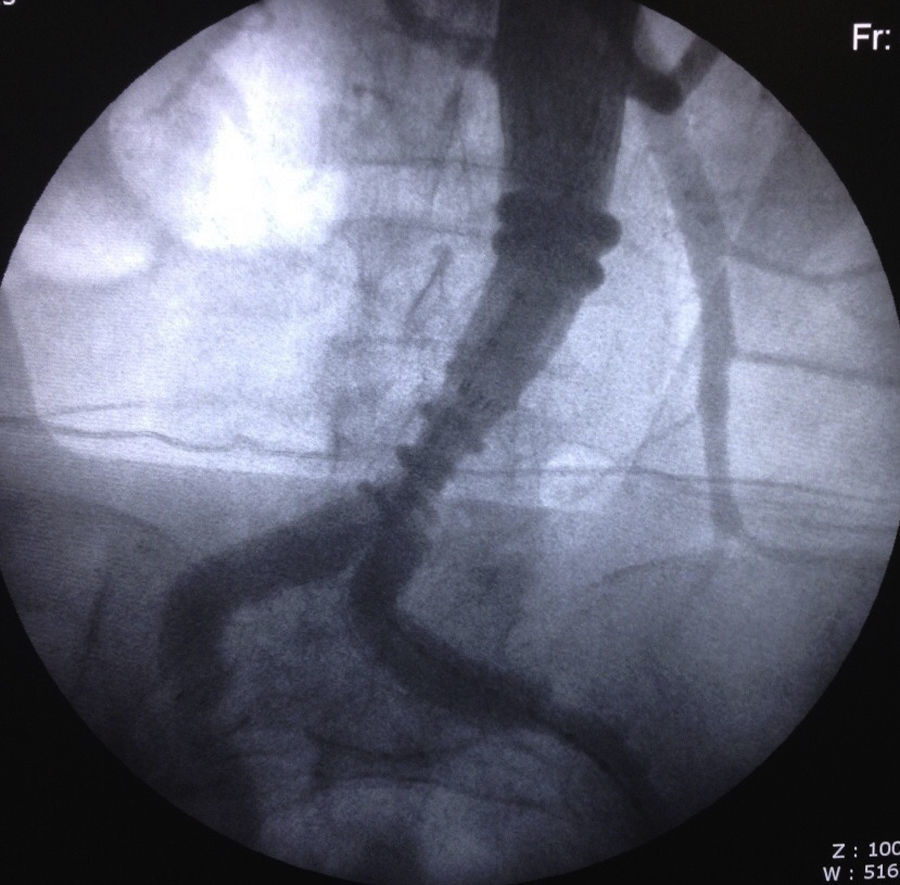

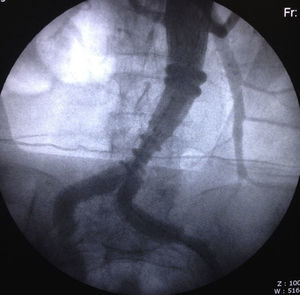

The case was analysed using CT angiography reconstructions and endovascular repair was scheduled. It was decided to use the Ovation trimodular endoprosthesis (Trivascular Inc.), due to its low introduction profile and navigability. Once the protocol was completed, the procedure was performed under sedation and local anaesthesia injection (lidocaine 2%) at the access sites. A percutaneous approach was used with an 18G needle puncture in both femoral arteries and right brachial access with micropuncture equipment and a 4Fr introducer. Then initial aortography was performed to locate the renal arteries. Once located, the image was fixed and the main body of the endoprosthesis was inserted through the right femoral access, releasing the suprarenal mount. Next the acrylic was applied via injection to the endoprosthesis body which sealed the proximal neck of the aneurysm sack. Afterwards the guide wire was introduced through the humeral access to place the left iliac prosthesis module, the right iliac module was deployed. In the final aortography, complete exclusion of the aneurysm sack was observed with no evidence of endoleaks (Fig. 2). The femoral accesses were closed with percutaneous closure systems (Angioseal®) and the humeral access with compression. Two days after the placement, the patient was progressing favourably, tolerating oral intake, walking without pain, with no signs of bruising in the access vessels. Therefore, it was decided to discharge her to her home. At the outpatient follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic and resumed normal daily activities.

DiscussionThe options to repair AAA include open surgery with a transabdominal or retroperitoneal approach or endovascular repair, which consists of inserting an endoprosthesis in the aortic lumen that effectively excludes the blood flow from the aneurysm, which minimises the risk of rupture.

Endovascular repair of an AAA is less invasive than the alternative, open surgery, and the success rate for this technique varies between 83% and more than 95%.9 The thirty-day mortality rate after elective surgery in large randomised trials varies between 2.7% and 5.8%10 and is influenced by the volume of procedures performed at the hospital and the surgeon's experience. It has been pointed out in several trials that the short-term morbidity and mortality rates of endovascular therapy are lower than those of open surgery, which makes it more suitable for high-risk patients.11 Other advantages of endovascular repair are found in a shorter hospital stay, less recovery time, and less blood loss.

The endoprosthesis was chosen in particular because of the system's low profile (14Fr), since we had to deal with small diameter access vessels, and the flexibility of the modules enabled ascending through the tortuous anatomy of the iliac arteries. Another of this system's advantages is the “personalised” closure of the proximal neck through rings filled with acrylic. Another advantage of this endoprosthesis is that it can be inserted in proximal necks smaller than 10mm.

Despite the advantages presented above, the mortality rate for both procedures are equivalent by approximately the fourth year, and in the endovascular repair group late complications can appear such as endoleaks, migration/displacement of the graft, and spontaneous thrombosis with a need for a second intervention.12

Currently, there are fewer and fewer cases that are outside the scope of minimally invasive treatment due to anatomical characteristics. However, in a condition as complex and with as high a mortality as aneurysms, the choice of surgical procedure for the candidate must be made with caution, taking into account the comorbidities (respiratory, cardiac, and neurological) and life expectancy. In young patients with few comorbidities and a higher life expectancy, open surgical treatment has not been displaced. It is necessary to specify that we have only spoken here regarding intact aneurysms, since perioperative mortality and complications in ruptured aneurysms is clearly higher.

The “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga” General Hospital of Mexico has the infrastructure and a team of trained professions to assess and effectively treat complex conditions such as aortic aneurysms, offering timely, comprehensive care to our patients.

Ethical disclosureProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.