To review a poorly studied pathology in the scientific literature.

Material and methodsAn observational, longitudinal and ambispective study of a series of 51 intramuscular lipomas in 50 patients. The frequency distribution of qualitative variables, and the median and the interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables were calculated. The relationship between the size of the lipomas (recoded into two values) and the study variables were analyzed using the Fisher exact test.

ResultsMen made up 62% of the series, and the median age was 61 years, with 55% of the total being overweight. About half of the patients were diagnosed in the upper limb. More than three-quarters (78%) were strictly intramuscular lipomas. Location, clinical and image presentation, treatment and results are described.

DiscussionIntramuscular lipomas have their own particular characteristics. Nevertheless, MRI is sometimes unable to distinguish them from well differentiated liposarcomas. Using size as the only criterion for referring a patient with a soft tissue injury to a reference center is still debatable.

ConclusionsPatients with intramuscular lipomas, although they may be typical in their presentation, especially when they are large and show findings that can be confused with a well-differentiated low grade liposarcoma, should be treated in experienced centers.

Recordar una enfermedad poco tratada en la literatura científica.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, longitudinal y ambispectivo de una serie de 51 lipomas intramusculares en 50 pacientes. Se ha calculado la distribución de frecuencias de las variables cualitativas y la mediana y el rango intercuartil (RIC) de las cuantitativas. La relación entre el tamaño de los lipomas (recodificada en 2 valores) y las variables de estudio se ha analizado con el test exacto de Fisher.

ResultadosEl 62% de los pacientes de la serie fueron varones y la mediana de edad, 61 años, con sobrepeso en el 55% del total. Se describe su localización, sus características de presentación clínica y de imagen, su tratamiento y resultados.

DiscusiónLos lipomas intramusculares tienen un aspecto característico, aunque a veces la RM no los distingue de liposarcomas bien diferenciados. El tamaño como criterio único de derivación de un paciente con una lesión de partes blandas a un centro de referencia es discutible.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con lipomas intramusculares, aunque estos puedan ser típicos en su presentación, sobre todo cuando sean grandes y muestren signos que los puedan confundir con liposarcomas bien diferenciados de bajo grado, se deberían tratar en centros con experiencia.

A deep tumor of over 5cm in diameter, not necessarily painful, which grows or reappears after excision, should be considered as a sarcoma until proven otherwise and treated accordingly. This would involve completing a study of the lesion and referring the patient to a reference center to receive specific treatment.1,2

Intramuscular lipomas (IM) are benign adipose tumors of the soft tissues which may resemble sarcomas due to their size, deep location and occasionally infiltrative growth.3 Being aware of their existence is fundamental in order to treat them correctly.4

The aim of the present study is to increase awareness of a disease which, whilst not infrequent and apparently trivial, is rarely mentioned in the scientific literature5–8 and with series of relatively few cases.4,9–12 In addition, it is often overlooked because it is half way between different specialties, so its management occasionally leads to doubts regarding diagnosis, location and type of treatment.

Material and methodWe conducted an observational, longitudinal and ambispective study of a series including 50 patients presenting 51 intramuscular lipomas who were treated consecutively at the Musculoskeletal Tumor Unit of Leon University Healthcare Complex, between July 2006 and June 2013. In total, 39 patients (78%) came from the Leon healthcare area, whilst 11 (22%) were from other healthcare areas in the autonomous region of Castilla y Leon. A total of 49 cases (96%) were newly diagnosed, whilst 2 cases were recurrences of lesions treated previously at other centers (1 patient with 2 recurrences who had undergone radiotherapy after the first episode).

In total, 34 cases (67%) were treated surgically and the diagnosis of lipoma was confirmed through a conventional anatomopathological study. One case of intramuscular lipoma in the fibularis longus presented concomitant muscle fat degeneration. There were no cases of lipoblasts or cellular atypias. In the 17 cases not intervened, 2 of which are currently awaiting surgery, the diagnosis was obtained through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

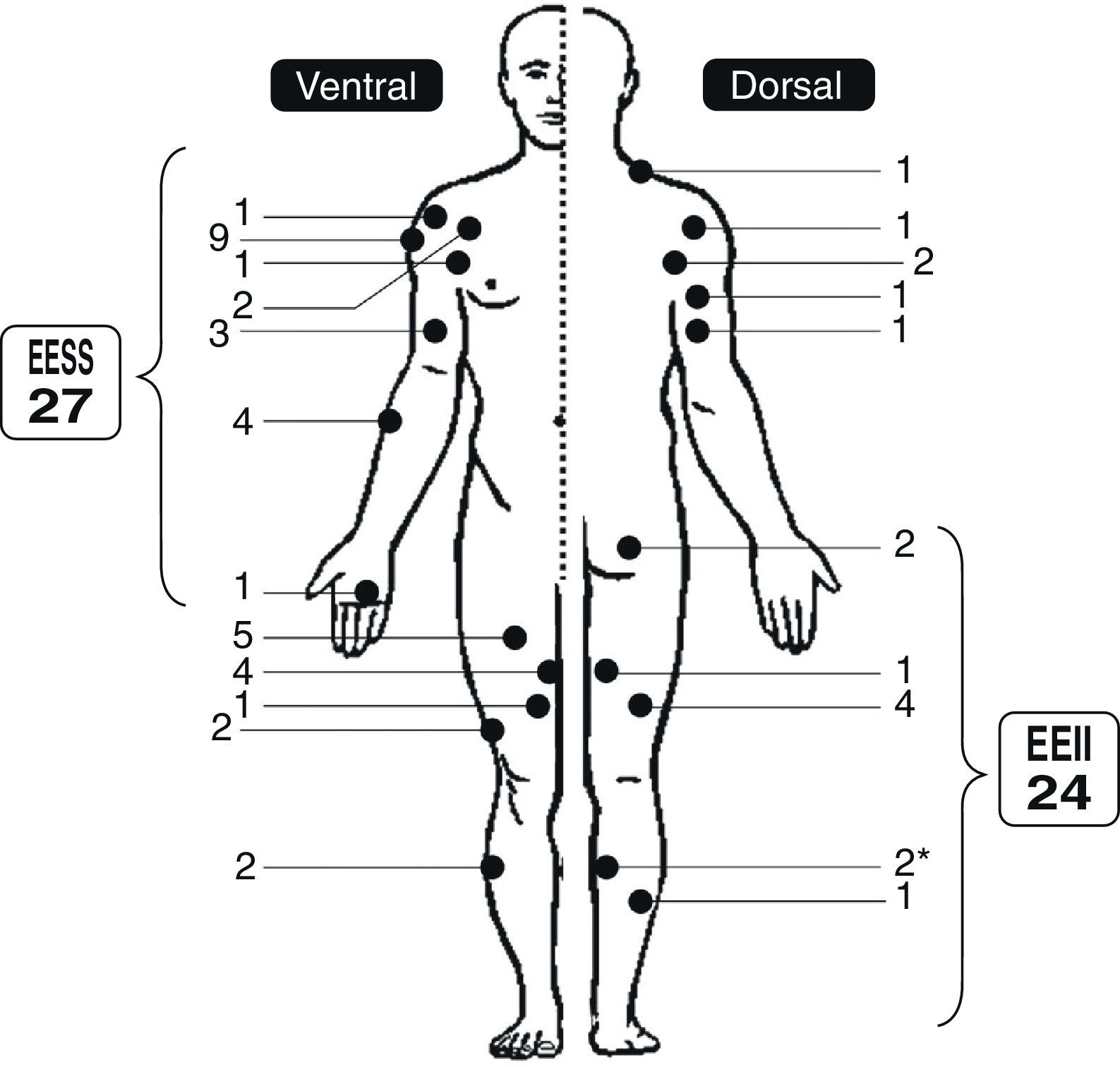

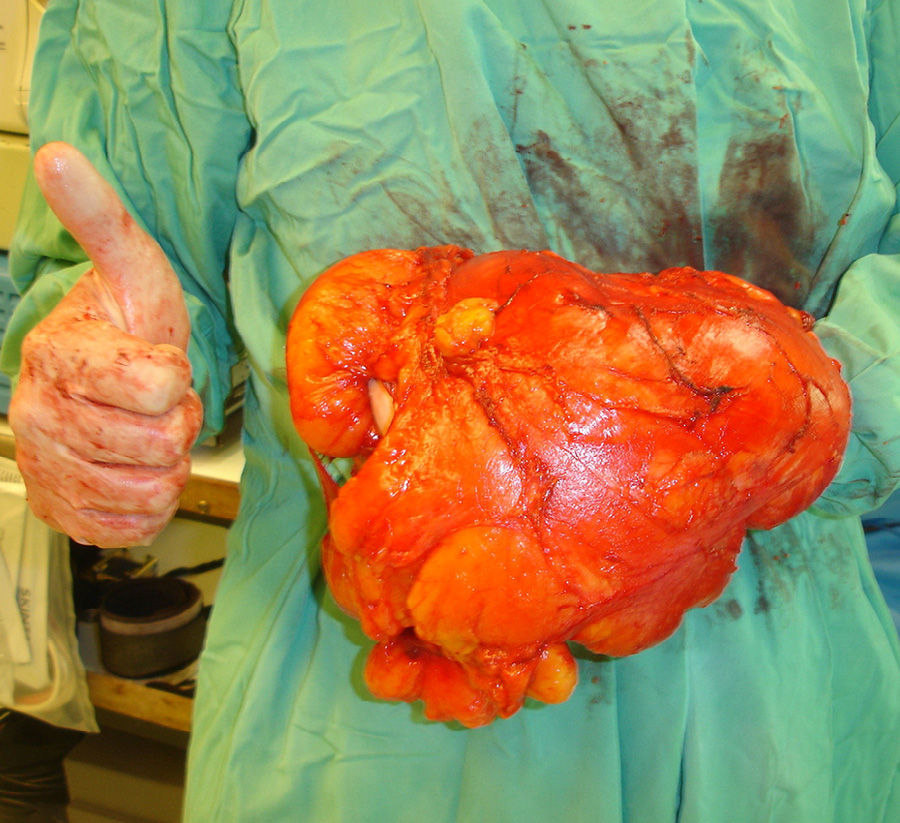

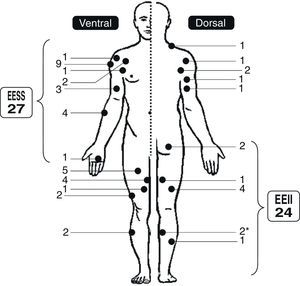

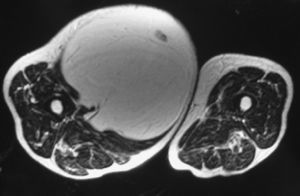

We analyzed the epidemiological, clinical and imaging characteristics of the series (Fig. 1), the treatment undergone by patients and the results of the surgical intervention. In total, 14 cases (27%), most of which were suspected of low-grade, well-differentiated liposarcoma through imaging tests, underwent closed tru-cut biopsies, guided by ultrasound in 3 cases, which ruled out this pathology. Surgical treatment, which in 31 patients was conducted by the same surgeon (LRRP), consisted of total tumor resection with marginal margins (31 cases: 91%) (Figs. 2 and 3) or intralesional margins (3 cases). After discharge, all intervened patients were routinely monitored in outpatient consultations and at the end of the study with a physical examination in all patients and MRI in cases of doubtful local recurrence (1 case). Patients who did not undergo surgery were monitored annually, with the MRI scan being repeated in most cases.

Resection specimen of the case in Fig. 2, excised with marginal margins. The image shows the large size of the tumor compared to the hand of the surgeon. Excellent clinical result and absence of recurrence at 6 years after the surgical intervention.

The results of surgical treatment included a description of the general complications, recurrence of the tumor or absence thereof and the functional results according to the modified scale of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS).13 The mean follow-up period for intervened patients was 34 months (range: 1–75 months). For patients who did not undergo surgery or were awaiting surgery after the first consultation at the Unit, the mean follow-up period was 26 months (range: 1–70 months).

The size of the cases, determined by the largest diameter in any MRI section, was recoded as a dichotomous categorical variable with section sizes in 5 and 8cm, which were related to the following independent variables: (a) linked to the characteristics of the patient (age over or equal/under 60 years, gender and body mass index [BMI] according to the WHO – normal, underweight and overweight –14), (b) and related to the characteristics of the tumor (location in upper or lower limbs, presence or absence of pain, growth of the tumor or lack thereof and presence or absence of septa in the MRI).

The information was entered into a database created with the software program Microsoft Access® 2000. Once the data had been revised and debugged, we exported them into the statistical software package SPSS® v.18, which we used to perform the statistical analysis. This consisted of a descriptive analysis of the variables, calculating the distribution of frequencies for qualitative variables and the median and the interquartile range (IQR) for the quantitative variables. We used the Fisher exact test to analyze the relationship between the size recoded into dichotomous values and the study variables. In all cases we considered as statistically significant a value of α=.05.

ResultsEpidemiological resultsOf the 50 patients in the series, 31 (62%) were male and 19 (38%) were female. The median age was 61 years and the IQR was between 54 and 69 years. Identical values were obtained when only the 49 new cases were analyzed. Among males, the same variables were 59 years with an IQR between 53 and 71 years, while in females they were 63 years and an IQR between 55 and 67 years. The median BMI (weight/height2) was 26.5 with an IQR between 24.2 and 28.4, with 16 patients (31%) presenting normal weight, 28 being overweight (55%), 5 with type 1 obesity and 1 with type 2 obesity according to the WHO.

The location of the cases in the series is shown in Fig. 1. In total, 26 lipomas were diagnosed on the right side, 23 on the left and 1 was bilateral (both legs). Of the 51 lipomas, 40 (78%) were intramuscular (2 with submuscular extension), 10 (20%) were intermuscular (4 in the shoulder girdle – 2 of them with subdeltoid extension –, 1 in the forearm, 2 in the medial region of the thigh and 2 in the posterior compartment of the thigh) and 1 was subfascial (superficial to the biceps brachii).

Clinical and imaging resultsIn 48 cases (94%), the first symptom was a tumor discovered accidentally by the patient, in 4 cases with associated discomfort. In the patient with bilateral lesion, the second lipoma was discovered accidentally during an MRI scan to examine the first lipoma. In 1 patient the diagnosis of lipoma in the fibular muscles was accidental during an MRI due to a muscle injury. In another case, the diagnosis was reached by the association of the tumor in the forearm with a deficit for the extension of the first finger, which an electromyogram related to a lesion in the posterior interosseous nerve. Up to 12 patients reported some type of pain at the time of consultation in our Unit and 14 reported the impression that the tumor had grown in the past year.

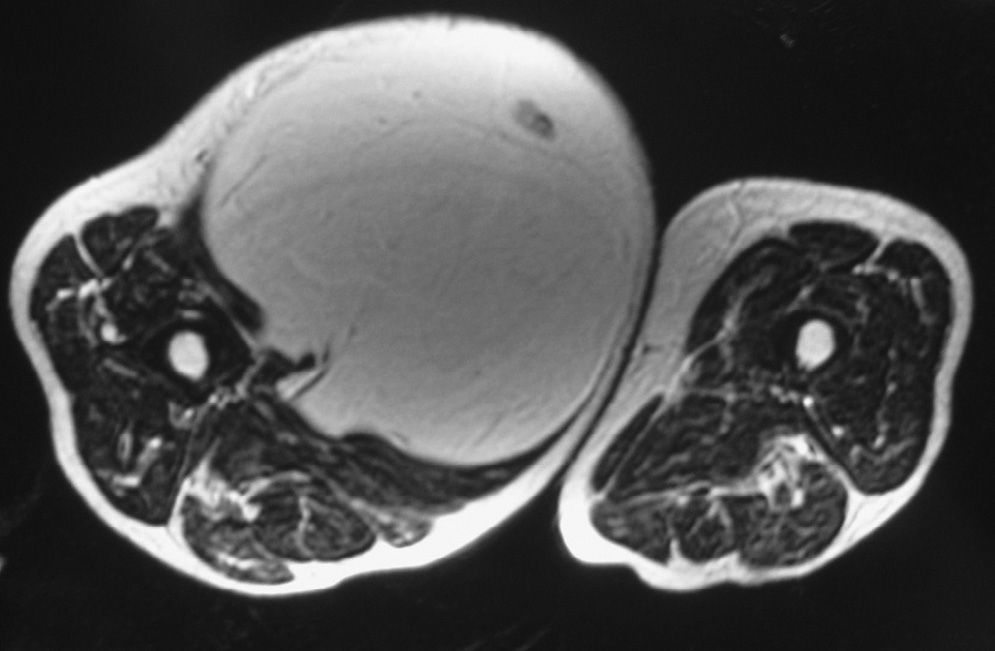

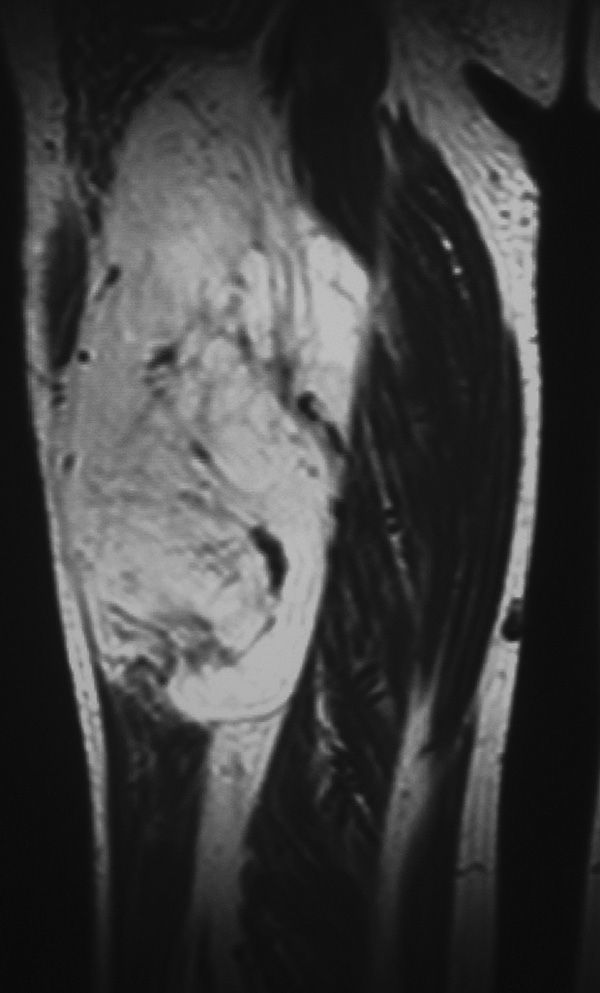

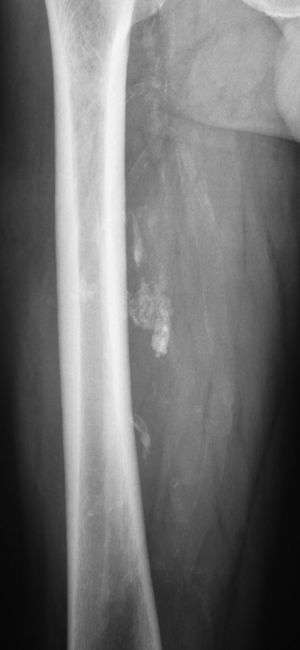

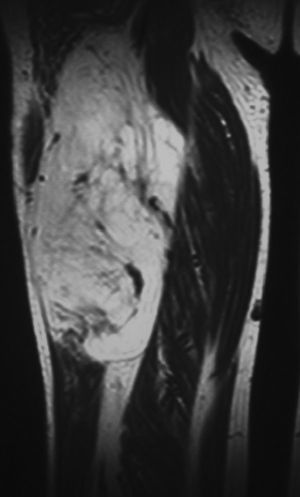

We obtained plain radiographs of the affected region for all patients. In 4 cases we discovered calcifications in the location of the soft tissue injury (Fig. 4), which was sometimes suspected. In 14 cases (27%) we obtained ultrasound scans, suggesting a diagnosis of lipoma (13 cases) and 1 hemangioma. In all cases we obtained an MRI scan of the tumor region in the habitual sequences with gadolinium injection in 16 patients. In 27 patients (53%) we observed septa, which were thin in 20 cases (2 with contrast enhancement) and thick in 7 (5 with contrast enhancement and 2 associated with nodular formations) (Fig. 5). We did not observe any cases with cysts or edema. The neighboring neurovascular bundle was compressed and displaced in 9 cases, contacted in 3 cases and enveloped by the tumor in 1 case of lipoma of the thigh. The median and IQR of the anteroposterior, transverse and vertical axes, respectively, were 42cm (IQR: 25–91cm), 47cm (IQR: 25–80cm) and 82cm (IQR: 59–133cm). The median size of the greater diameter was 90cm, with an IQR of 60–137cm. The radiologist issued a report of lipoma in 41 cases (80%), of lipoma or low-grade liposarcoma in 8 cases (16%) and of well-differentiated liposarcoma in 2 cases.

Coronal section of an MRI scan of the case in Fig. 4, showing multiple gross and irregular septa which lead to suspicion of low-grade liposarcoma. Excellent clinical result and absence of recurrence at 5 years after the surgical intervention.

None of the variables studied presented a statistically significant association with tumor size.

Results of surgical treatmentThe mean postoperative hospital stay was 2 days, with an IQR of 1–3 days, and a maximum stay of 11 days for 1 patient who suffered intraoperative bleeding due to an injured anterior humeral circumflex artery. A total of 6 patients experienced general postoperative complications which were resolved quickly with appropriate treatment: 1 seroma, 2 hematomas, 1 surgical wound dehiscence and 2 superficial infections.

At the end of the follow-up period, 1 patient in the series had died from lung cancer 3 years after the lipoma intervention. Neither in this patient until the moment of death nor in the rest of the patients at the end of the study did we note a recurrence of the lipomatous tumor, although the patient with 2 recurrences in the thigh and inguinal region presented a small tumor remnant in the control MRI conducted at 6 months postoperatively. Among the series of 34 intervened patients, the functional results according to the MSTS scale were excellent (30 points: 100%) in 30 patients (88%). In the remaining 4 cases, with lipomas in the thigh, shoulder girdle, thigh and forearm, the overall score was 28 points (93% functionality), 26 points (90%), 25 points (84%) and 17 points (60%), respectively. None of the patients in whom surgery was not recommended reported pain or functional limitation, and the tumor did not grow significantly since diagnosis.

DiscussionBenign lipomatous tumors comprise a large and complex variety of lesions: the classic lipoma and its variants (angiolipoma, myolipoma, ossifying lipoma, chondroid lipoma, spindle cell lipoma and pleomorphic lipoma), lipoblastoma, hibernoma and infiltrating lipomas, including lipomatosis.15,16 According to their location, which is usually solitary, classic lipomas are classified into superficial and deep.17 The latter, less common than the superficial and more frequent in the retroperitoneum, chest wall and proximal region of the limbs, are often described as intramuscular or intermuscular,10,18 although the terms are often grouped and include other forms which are not exactly within or between muscles.

The term intramuscular lipoma,19 which we will assume for academic purposes, includes benign tumors composed of mature fat cells with no atypia or lipoblasts deeper than the fascia which settle into a muscle (true intramuscular lipomas), often infiltrating,11 or between muscle groups (intermuscular lipoma), as well as the subfascial and submuscular or the parosteal, which some authors have considered as a separate entity. In our series of 51 classic deep lipomas, we considered 40 intramuscular forms, 10 intermuscular and 1 subfascial, although the same case could have presented various locations in different MRI sections. Five of the intra- and intermuscular cases presented submuscular extension. In general, all have usually been published as case reports,5–8 in series with relatively few cases,4,9–12 or without specifying a wider range of adipose tumors. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the largest series reported.

The epidemiology of intramuscular lipomas, which generally resembles our series, involves just under 2% of adipose tumors,6,20 occurring in patients of all ages, although most often in adults, with a slight predominance among males17 and indistinct location in the upper limbs and, more often, in the lower limbs, with the thigh as the most common.4,11,19 Without delving into the pathogenesis of the tumor, which is currently unknown, some authors have suggested a relationship with obesity.21 This was also perceived among our cases, two thirds of which were overweight or obese.14

Clinically, patients often report painless or minimally painful tumors of varying size and slow or no growth, with other semiology in rare cases.6 This was also observed in our series, where, for example, upon exploration 1 patient presented inability to extend the first finger due to posterior interosseous nerve injury of the forearm, similar to the case described by Lewkonia et al.22

Regarding complementary imaging tests, among which plain radiography and MRI are a requisite, most IM lipomas present the same findings as subcutaneous lipomas, which are unambiguous in typical cases.4,6,10,23 Radiographically, in addition to the radiolucent fatty area, it is also possible to identify signs of ossification or calcification, especially in cases with a long evolution. This occurred in 4 cases in our series. CT and MRI scans always show tissue identical to subcutaneous fat which does not uptake contrast, although this has been observed in a mild or moderate manner in some septa and capsules of some patients.24 This was also the case in 7 of our patients. Since they can contain other mesenchymal elements, especially fibrous connective tissue, in 46% of cases it is possible to observe septa as linear areas of increased attenuation in CT or linear reduced intensity in MRI, depending on the sequence employed.17,18 In our series, we identified septa in half the patients. In the same vein, a substantial percentage of lipomas do not present adipose findings.25

The differential diagnosis of intramuscular lipomas includes other benign adipocytic tumors, which have been mentioned at the beginning of this discussion, as well as injuries that may contain fat (hemangiomas, elastofibroma dorsi, hernias containing fat and muscle atrophy with fat replacement).17 It is important to distinguish them from soft tissue sarcomas,2,16 and particularly the well-differentiated liposarcoma subtype, which can be mistaken both through clinical and imaging findings.10,17,25,26 In fact, in 8 of our cases the radiologist was unable to distinguish between lipoma and low-grade liposarcoma, and in 2 cases he presented a diagnosis of well-differentiated liposarcoma which the biopsy did not confirm. Finally, when referring to ossifying or chondroid lipomas,5 the differential diagnosis must include myositis ossificans, calcified or ossified tumors (liposarcoma, synovial sarcoma, extraskeletal osteosarcoma and extraskeletal chondrosarcoma and soft tissue chondroma), hemangiomas and calcified bursae.

Insisting on tumor size, a large tumor deeper than the fascia should be considered as a sarcoma until proven otherwise. The size limit for this suspicion is 5cm, with mean sizes at diagnosis ranging between 8 and 10cm in soft tissue sarcomas of the limbs.27 Nevertheless, the role of size as the sole criterion for referral of a patient with a soft-tissue lesion to a reference center is questionable, as it has been observed that 10% of malignant lesions can measure less than 5cm and more than half of benign lesions may be larger than 5cm.28 In our series, 46 (90%) of the cases measured 5cm or more and 33 (65%) cases measured 8cm or more. We did not identify any factor related to size.

Treatment of symptomatic intramuscular lipomas, which would not require prior biopsy in typical cases,18,23,24 consists in complete tumor resection with marginal margins or wide margins in cases of infiltrating tumors with acceptable surgical morbidity.12,18,19 Observation could be considered in asymptomatic patients without any diagnostic doubt, taking into account the fact that malignant transformation is exceptional. The few cases reported probably had a low degree of malignancy from the outset.17 Moreover, the variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma, which currently encompasses cases formerly known as atypical lipomas, has a tendency toward local recurrence,19,29 but not toward metastasis, with a small probability of dedifferentiation and consequent worsening of the prognosis.17 In our series, we performed closed, tru-cut biopsies in 14 cases, usually when we doubted the possibility of a low-grade liposarcoma. Nevertheless, we did not perform it in cases when surgical resection margins would not change regardless of whether it were a lipoma or a liposarcoma, as in those cases in which the tumor contacted a major neurovascular bundle which we were not going to sacrifice. In these patients, our approach was to inform patients of the diagnostic uncertainty and the need for adjuvant radiotherapy subsequent to surgery if they proved malignant.

On the other hand, the results which can be expected of surgical treatment are often satisfactory from the oncological standpoint, although local recurrences have been reported in 80% of cases,4 generally in connection with incomplete surgical resections6 and erroneous initial diagnoses.19 Excluding these factors, the true incidence of recurrence would be around 4% of cases and would be independent of patient age and gender, as well as tumoral size and location.19 The functional outcome would depend on the muscles sacrificed, if this were to be the case. Otherwise, and in the absence of complications, recovery would be the norm. All the results of our cases were satisfactory or highly satisfactory and we did not observe any local recurrences, excluding a tumor remnant left in 1 patient and accepting the biases mentioned below.

The limitations of our study are manifold. The first concerns the retrospective nature of the study. The second would be the selection bias involved in grouping all our cases as intramuscular lipomas without cytogenetic confirmation, as currently recommended by some authors, which could have meant labeling some of our cases as true dedifferentiated liposarcomas.19 Similarly, in another case located in the fibula, we identified fatty infiltration between some muscle fibers which might have corresponded to lipomatous muscle degeneration, rather than intramuscular lipoma, as concluded by the pathologist, whose diagnosis we assumed. The third involves the relatively short follow-up period of some intervened cases, with an overall mean follow-up period of 33 months. A period of 48 months has been suggested as the usual mean period of recurrence in IM and atypical lipomas.19 In the series of Su et al.,12 the follow-up period was 40 months. The fourth limitation of our study, also related to the possibility of undiagnosed recurrences, was that the test on which we relied in order to rule out recurrence during follow-up was usually physical examination, which is less sensitive than MRI, which was only performed on 1 intervened patient. Nevertheless, we believe that the work meets the objective of refreshing the memory of this disease and provides practical guidance on its management, which could be a cause for doubt in some cases.

In conclusion, although they may be typical in their presentation, especially when they are large and show signs that may lead to confusion with well-differentiated low-grade liposarcomas, intramuscular lipomas should be treated at experienced centers.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Committee on Responsible Human Experimentation, as well as the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ramos-Pascua LR, Guerra-Álvarez OA, Sánchez-Herráez S, Izquierdo-García FM, Maderuelo-Fernández JÁ. Lipomas intramusculares: bultos benignos grandes y profundos. Revisión de una serie de 51 casos. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:391–397.