To assess complications and factors predicting one-year mortality in patients on anti-platelet agents presenting with femoral neck fractures undergoing hip hemiarthroplasty surgery.

Material and methodsA review was made on 50 patients on preoperative anti-platelet agents and 83 patients without preoperative anti-platelet agents. Patients in both groups were treated with cemented hip hemiarthroplasty. A statistical comparison was performed using epidemiological data, comorbidities, mental state, complications and mortality. There was no lost to follow-up.

ResultsThe one-year mortality was 20.3%. In patients without preoperative anti-platelet agents it was 14.4% and in patients with preoperative anti-platelet agents was 30%. Age, ASA grade, number of comorbidities and anti-platelet agent therapy were predictors of one-year mortality.

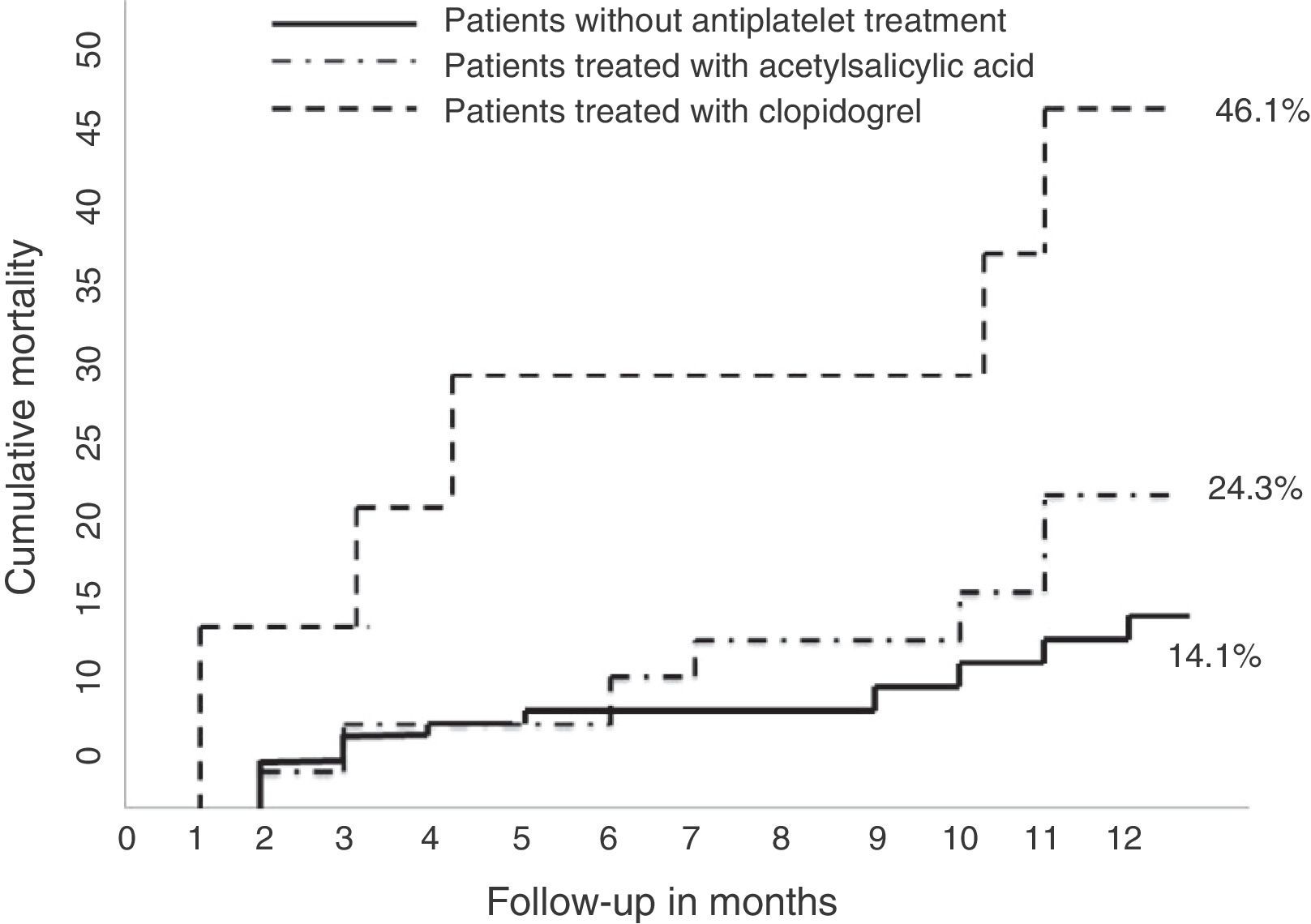

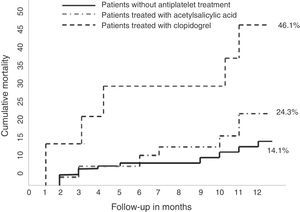

The one-year mortality of patients on clopidogrel was 46.1%, versus 24.3% in patients on acetylsalicylic acid.

ConclusionPatients with preoperative anti-platelet therapy were older and had greater number of comorbidities, ASA grade, delayed surgery, and a longer length of stay than patients without anti-platelet therapy. The one-year mortality was higher in patients with preoperative anti-platelet therapy.

Evaluar las complicaciones y la mortalidad en pacientes antiagregados con fractura cervical desplazada de cadera tratada con prótesis parcial.

Material y métodoEstudio de 133 pacientes en el período 2008 a 2010 que se distribuyeron en 2 grupos, con tratamiento antiagregante en el momento del ingreso (50 pacientes) y sin tratamiento antiagregante (83 pacientes). Todos tratados mediante sustitución parcial de cadera con implante de prótesis parcial modular cementada. Se valoraron los datos epidemiológicos, comorbilidades, estado mental, complicaciones y mortalidad. No hubo pérdidas de seguimiento.

ResultadosLa mortalidad anual de la serie completa fue del 20,3%; en pacientes no antiagregados, del 14,4%, y en pacientes antiagregados, del 30%. Los predictores de mortalidad a los 12meses fueron la edad, el grado ASA, el número de comorbilidades asociadas y la antiagregación.

Los pacientes antiagregados con clopidogrel tuvieron una mortalidad del 46,1%, frente al 24,3% de los pacientes antiagregados con ácido acetilsalicílico.

ConclusionesLos pacientes antiagregados tenían mayor edad, número de comorbilidades, grado ASA, demora quirúrgica y estancia hospitalaria que los no antiagregados. A los 12meses de la cirugía la mortalidad acumulada ha sido mayor en pacientes antiagregados que en los no antiagregados.

The association of hip fractures with anti-platelet (or anti-aggregant) drugs is increasingly common among patients suffering hip fractures, particularly elderly patients, and this conditions their perioperative management due to the theoretical risks associated to surgical bleeding.

Anti-aggregant drugs are indicated as prophylaxis or treatment of arterial thrombotic processes, with a variable response due to patient idiosyncrasies, non-compliance with therapeutic patterns and drug interactions, as these subjects are often polymedicated.1

There is a general consensus that surgical treatment is the best option for hip fractures, as it reduces morbidity and mortality.2 Delaying surgery in patients with anti-aggregants aims to prevent the onset of anesthetic and hemorrhagic complications, as well as the need for transfusions. On the other hand, delaying the intervention could increase morbidity and mortality and delay functional recovery.

In 2007, the Spanish Society of Traumatology and Orthopedic Surgery (SECOT) published the Guide for Elderly Hip Fracture Patients, which indicated that the optimal moment for surgery depended on the general condition of each patient, as well as their comorbidities and concomitant treatments. In addition, the delay was also influenced by intrinsic factors of the healthcare system or working routine of each hospital. The association of both groups of factors led to surgical delays of over 24h becoming common at our hospitals. Regarding the management of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) among patients with hip fractures, the Guide stated that although the decision about when to carry out the surgery in this kind of patients should contemplate the risks and benefits in each specific case, delaying the operation was not justified and patients should be intervened as soon as possible.3 Nevertheless, it was not until 2011 that the Spanish Society of Anesthesiology, Reanimation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR) published the Clinical Practice Guideline for the Perioperative Management of Anti-platelet Drugs in Non-Cardiac Surgery, which indicated that the preoperative decision to interrupt or continue treatment with anti-platelet agents should always be based on a detailed and individualized assessment of each patient which evaluated the probable increase in thrombotic risk in case of interruption versus the hypothetical increase of the hemorrhagic risk derived from its maintenance. The Guide recommended suspending ASA between 2 and 5 days and clopidogrel between 3 and 7 days for the perioperative management of non-cardiac surgery.4

The difference in criteria between anesthesiologists and traumatologists at our center led us to consider the hypothesis that there was a greater incidence of complications and mortality 1 year after the surgery comparing between patients with and without anti-platelet therapy who suffered displaced subcapital fractures of the femur treated through cemented hip hemiarthroplasty.

Material and methodBetween January 2008 and December 2010, our database of hip fractures registered a total of 339 proximal femoral fractures, of which 152 (44.8%) were subcapital femoral fractures and, out of these, 140 (41.2%) were displaced. Of the 140 patients with displaced subcapital femoral fractures, 83 (59.3%) were not taking any anticoagulant or anti-aggregant medication at the time of hospital admission, 50 (35.7%) patients were taking anti-aggregant medication and 7 (5%) patients were taking anticoagulant medication. Patients with pathological fractures, multiple trauma, coagulopathies, thrombocytopenia (platelet counts under 150×109/l), following anticoagulant treatment with dicoumarins, and those with absolute contraindication for interruption of the anti-aggregant treatment were all excluded, as they did not correspond to the objective of the study. There were no follow-up losses.

The demographic data of each patient were recorded during hospital admission, as were the type of fracture, type of intervention, surgical delay, days of hospital admission and associated comorbidities. Preanesthetic risk was assessed through the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) scale.5 In order to determine the associated comorbidities we considered those with a greater influence on the prognosis of the fracture, such as arterial hypertension (AHT), cardiopathy, pulmonary disease, nephropathy, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), diabetes, rheumatism, Parkinson's and dementia.3 The assessment of cognitive function was carried out through the mini-mental test with a maximum score of 10, considering a score of 6 or lower as suggestive of dementia.6 At the time of admission, patients were examined by the Internal Medicine and Emergency Service, which focused on their associated medical pathology and indicated the removal of anti-aggregant treatment (ASA 300mg in 19 patients, ASA 100mg in 18 patients and clopidogrel in 13 patients) regardless of the type of antiaggregation and dosage, initiating antithrombotic prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin 40U subcutaneously every 24h). Surgical delay was established by the Anesthesiology and Reanimation Service based on the type of anti-aggregant treatment of each patient. The associated comorbidities were stabilized during this period if necessary, but patients were not intervened until they had completed the period of antiaggregation removal indicated by the Anesthesiology and Reanimation Service.

All patients were intervened under spinal anesthesia using a cemented modular partial prosthesis (Polarstem, Smith & Nephew, UK), through a posterior approach with the usual technique. Antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazolin, 2g previously and 1g every 8h, 3 doses, postoperative intravenous; in allergic subjects, vancomycin 1g previously and 1g in a single postoperative intravenous dose) and antithrombotic prophylaxis (enoxaparin 40U subcutaneously every 24h for 1 month after intervention) were identical in all cases. Surgical drainage was used systematically in all cases and removed after 48h, and the analysis was requested on the same day as the surgery. Blood transfusion was indicated if postoperative Hb was under 8g/dl. Patients were moved to a chair on the first day after the intervention and started to walk using a frame on the second day, if possible. The Internal Medicine Service was consulted before indicating reintroduction of anti-aggregant therapy after the surgery.

In order to record the complications and mortality of the process, patients were reviewed at the outpatient clinic 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after the surgery. Patients were contacted by telephone if they did not attend the review.

The influence of hip fractures on mortality was established until the first year after the trauma, so this follow-up period was indicated as end point, unless death occurred sooner.7

Patients with the same type of fracture and surgical treatment, conducted during the same period of time, and who were not taking anti-aggregant medication at the time of hospital admission were considered as control group in terms of comparing mortality and complications between patients who were on anti-aggregants and those who were not. The type of prosthesis, surgical procedure, postoperative management and revisions in outpatient consultation were identical to those of the group of anti-platelet patients.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was conducted using the statistics software package SPSS. We carried out univariate studies, using the Mantel–Haenszel non-parametric or the chi squared test with Yates correction, as applicable, for qualitative variables, as well as the Mann–Whitney non-parametric or Wilcoxon sign test, or the paired or independent Student t-test, as applicable, for continuous variables. In the case of univariate tests with significant relationship, we used as independent covariates in the logistic regression analysis with respect to mortality. We considered as significant a value of P equal to or lower than .05.

ResultsThe sample of patients with anti-aggregant treatment comprised 50 subjects with a mean age of 84.1 years (range: 68–96 years; SD: 6.6 years). The gender distribution was 37 females (74%) and 13 males (26%). The right hip was affected in 26 patients (52%), and the left in 24 (48%).

Regarding associated comorbidities, 39 patients (78%) were diagnosed with arterial hypertension (AHT), 15 (30%) with cardiopathy, 12 (24%) with diabetes, 12 (24%) with dementia, 10 (20%) with CVA, 7 (14%) with pulmonary disease and 2 (4%) with Parkinson's. When grouped, 21 patients (42%) presented 1 or 2 associated comorbidities, and 29 patients (58%) suffered 3 or more associated comorbidities. According to the preanesthetic ASA classification, there were 10 patients (20%) with grade II, 35 (50%) with grade III and 5 (10%) with grade IV. The score in the mini-mental test was 6 points or less (indicative of dementia) in 12 patients (24%).

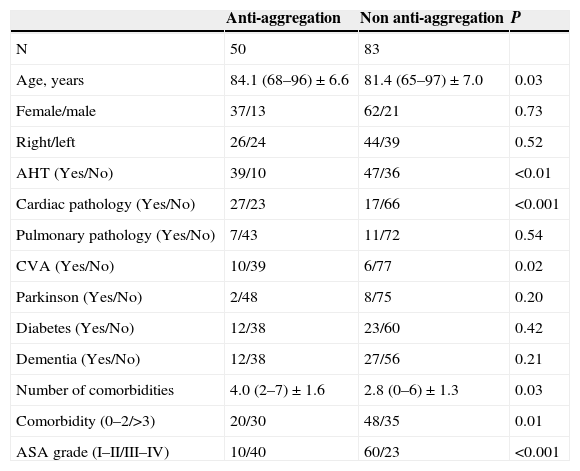

Comparison of the preoperative data from both groups (Table 1) showed a significant difference regarding age—which was higher in the group of patients treated with anti-platelet drugs—and the diagnosis of AHT, heart pathology and CVA, with a higher presence in the group of anti-platelet patients. The number of comorbidities and ASA grade III/IV cases was also higher in the group of anti-platelet patients, with a significant difference. The mean value of preoperative Hb was of 12.9g/dl (range: 8.5–17.2; SD: 1.7) among anti-platelet patients, and of 13.0g/dl (range: 9.4–17.6; SD: 1.6) among patients not treated with anti-aggregants, with no significant difference (P=.87).

Preoperative data, both groups.

| Anti-aggregation | Non anti-aggregation | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 50 | 83 | |

| Age, years | 84.1 (68–96)±6.6 | 81.4 (65–97)±7.0 | 0.03 |

| Female/male | 37/13 | 62/21 | 0.73 |

| Right/left | 26/24 | 44/39 | 0.52 |

| AHT (Yes/No) | 39/10 | 47/36 | <0.01 |

| Cardiac pathology (Yes/No) | 27/23 | 17/66 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary pathology (Yes/No) | 7/43 | 11/72 | 0.54 |

| CVA (Yes/No) | 10/39 | 6/77 | 0.02 |

| Parkinson (Yes/No) | 2/48 | 8/75 | 0.20 |

| Diabetes (Yes/No) | 12/38 | 23/60 | 0.42 |

| Dementia (Yes/No) | 12/38 | 27/56 | 0.21 |

| Number of comorbidities | 4.0 (2–7)±1.6 | 2.8 (0–6)±1.3 | 0.03 |

| Comorbidity (0–2/>3) | 20/30 | 48/35 | 0.01 |

| ASA grade (I–II/III–IV) | 10/40 | 60/23 | <0.001 |

AHT: arterial hypertension; ASA grade: grade according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; CVA: cerebrovascular accident.

Quantitative variables are shown as mean (range)±standard deviation.

The mean surgical delay was of 4.2 days in the group of patients treated with anti-platelet drugs and of 3.4 days in the group of those who were not, with no significant differences (P=.08). The duration of hospital admission was similar in both groups, with a mean 9.7 days in the group of antiaggregation patients compared to 9.3 days in the group of non antiaggregation patients (P=.61). The mean value of postoperative hemoglobin was 10.7g/dl (range: 6.5–14.1; SD: 1.6) in the group of antiaggregation patients and 10.8g/dl (range: 6.8–14; SD: 1.5) in the group without anti-platelet therapy; very similar in both groups (P=.92). A total of 7 patients (14%) in the antiaggregation group required a blood transfusion in the immediate postoperative period, compared to 21 patients (25%) in the non anti-aggregation group, with no significant differences (P=.09). The mean number of packed red blood cells transfused was 2.2 (range: 2–4; SD: 0.7) in the group of patients with anti-platelet treatment and of 2.5 (range: 2–5; SD: 0.9) in the group of patients without anti-platelet treatment, with no significant differences (P=.51).

There were no intraoperative complications or need for revision surgery 1 year after the intervention in any of the 2 groups. Two patients (4%) in the anti-platelet group presented superficial infection, compared to 4 patients (4.8%) in the group without anti-platelets, with no significant differences (P=.59). All cases were resolved through periodic cures and antibiotic therapy. There were medical complications in 9 (10.8%) patients without anti-platelet treatment and in 9 (18%) anti-platelet patients (P=.18). The ASA classification grade was not associated with a greater incidence of surgical (P=.25) and medical (P=.41) complications.

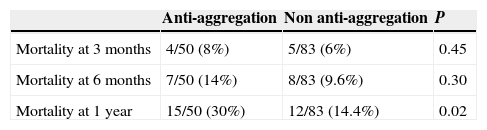

At 12 months after the intervention, the cumulative mortality taking both groups into account was 20.3% (27 patients). None of the patients died during hospital admission. There was a significant difference (P=.02) between mortality in the group of antiaggregation patients (15 patients, 30%) and that in the group of non anti-aggregation patients (12 patients, 14.4%) (Table 2). Simple regression analysis identified the following risk factors for mortality at 1 year: age (P=.01), antiaggregation treatment (P=.03), ASA grade (P=.03) and the number of associated comorbidities (P=.02). Multiple regression analysis identified an association of the following factors with mortality at 1 year: (P=.01), antiaggregation treatment (P=.02), ASA grade (P=.02) and the number of associated comorbidities (P=.009). The odds ratio for mortality among anti-aggregation patients was 1.6 (95% CI: 1.0–2.5), compared to 0.6 (95% CI: 0.4–1.0) in the group of non anti-aggregation patients.

In the group of patients with anti-platelet agents, the mean age of deceased cases was 87.8 years, significantly higher (P=.007) than in the case of survivors, with a mean age of 82.5 years. The mean number of associated comorbidities was higher among deceased cases (4.0 versus 2.8), with a significant difference (P=.03). The number of patients with ASA grade III/IV was also higher among deceased cases (P=.05). There were no differences in gender (P=.13), surgical delay (P=.75), presence of 3 or more associated comorbidities (P=.17) and presence of dementia (P=.21).

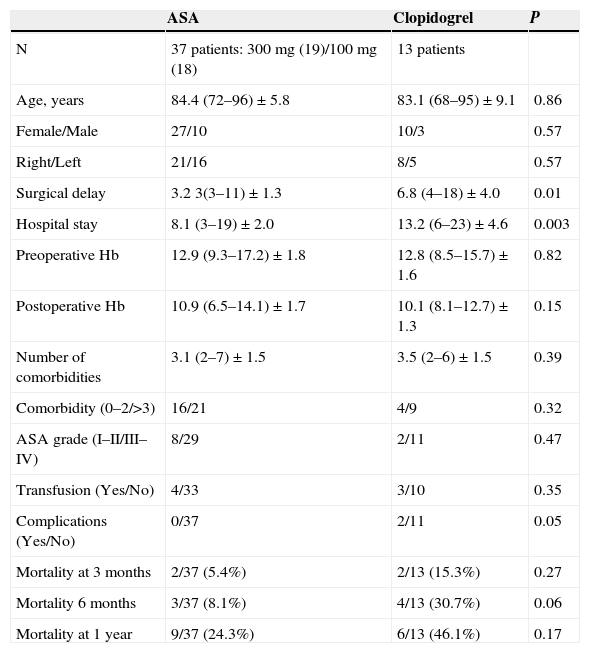

Out of the 50 patients taking anti-platelet agents, 37 were treated with ASA and 13 with clopidogrel. The general data of both groups is shown in Table 3. The only differences between both groups were found in surgical delay, hospital stay and postoperative complications. At 12 months after the surgery, 6 patients (46.1%) following anti-aggregation treatment with clopidogrel had died, compared to 9 patients (24.3%) following anti-aggregation treatment with ASA (Fig. 1).

Data from patients treated with anti-platelet drugs.

| ASA | Clopidogrel | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 37 patients: 300mg (19)/100mg (18) | 13 patients | |

| Age, years | 84.4 (72–96)±5.8 | 83.1 (68–95)±9.1 | 0.86 |

| Female/Male | 27/10 | 10/3 | 0.57 |

| Right/Left | 21/16 | 8/5 | 0.57 |

| Surgical delay | 3.2 3(3–11)±1.3 | 6.8 (4–18)±4.0 | 0.01 |

| Hospital stay | 8.1 (3–19)±2.0 | 13.2 (6–23)±4.6 | 0.003 |

| Preoperative Hb | 12.9 (9.3–17.2)±1.8 | 12.8 (8.5–15.7)±1.6 | 0.82 |

| Postoperative Hb | 10.9 (6.5–14.1)±1.7 | 10.1 (8.1–12.7)±1.3 | 0.15 |

| Number of comorbidities | 3.1 (2–7)±1.5 | 3.5 (2–6)±1.5 | 0.39 |

| Comorbidity (0–2/>3) | 16/21 | 4/9 | 0.32 |

| ASA grade (I–II/III–IV) | 8/29 | 2/11 | 0.47 |

| Transfusion (Yes/No) | 4/33 | 3/10 | 0.35 |

| Complications (Yes/No) | 0/37 | 2/11 | 0.05 |

| Mortality at 3 months | 2/37 (5.4%) | 2/13 (15.3%) | 0.27 |

| Mortality 6 months | 3/37 (8.1%) | 4/13 (30.7%) | 0.06 |

| Mortality at 1 year | 9/37 (24.3%) | 6/13 (46.1%) | 0.17 |

ASA: acetylsalicylic acid; ASA grade: grade according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; Hb: hemoglobin.

Quantitative variables are shown as mean (range)±standard deviation. Mortality is indicated as cumulative.

The limitations of our study include being a retrospective study and the scarce numbers of patients following antiaggregation treatment with clopidogrel and suffering displaced subcapital femoral fracture. On the other hand, we believe that the advantages include not having any losses during follow-up and a uniform sample as regards the type of fracture, surgical treatment, postoperative management and monitoring.

In our study, mortality at 12 months was higher among patients with anti-platelets (30%) than among those not following antiaggregation treatment (14.4%). Furthermore, in the anti-platelet group, mortality was higher among those patients treated with clopidogrel (46.1%) than those treated with ASA (24.3%). Maheshwari et al.8 reported mortality at 12 months among 26% of 31 patients suffering proximal femoral fracture following antiaggregation treatment with clopidogrel, although the series was not uniform regarding the type of fracture and surgical treatment. Mas-Atance et al.9 indicated a mortality of 23.8% at 12 months in 105 patients with proximal femoral fracture who were not following anti-aggregation treatment versus 32.4% in 34 anti-platelet patients intervened before 48h, as well as 47.2% in 36 anti-platelet patients intervened after the fifth day of admission. However, like the previous work, this series was not uniform regarding the type of fracture and surgical treatment.

The risk factors for mortality described in the literature are varied, although not uniformly. In a metaanalysis, Hu et al.10 indicated that advanced age, male gender, place of residence, limited capacity for walking prior to the fracture, dependence for daily life activities, ASA grade, multiple associated comorbidities, dementia, diabetes, cancer and heart pathology were all predictive factors of mortality among patients with hip fracture, although well-designed studies would be required to specify this evidence. In another study, Navarrete et al.11 identified gender and prior general condition as statistically significant risk variables for mortality at 1 year among patients suffering hip fracture. In a series of patients aged over 65 years and suffering cervical fractures treated with partial hip prostheses, Lim et al.12 found an annual global mortality of 11%, although significantly associated to age. Mas-Atance et al.9 reported an association between the Barthel index prior to the fracture and the number of transfusions and mortality at 12 months among patients with anti-platelets. Maheshwari et al.8 associated surgical delay as the only predictive factor of mortality at 1 year among patients following anti-aggregation treatment with clopidogrel. In our study, mortality at 1 year was significantly related to anti-aggregation, age, ASA grade and the number of associated comorbidities, in both the univariate and multivariate regression studies.

Surgical delay is a controversial factor in the treatment of hip fractures. In general, clinical guides3,13 recommend carrying out the intervention within 24–36h, whenever the condition of the patient allows it, in order to reduce morbidity and mortality, as long as this haste to perform the intervention does not detract from optimizing medical aspects. The published works show varying results. After reviewing 52 published studies, Khan et al.14 concluded that early surgery (before 48h) was associated to lower mortality with no increase of postoperative complications. Moran et al.15 indicated a higher mortality at 90 days and at 1 year among 2660 patients intervened for hip fractures after the fourth day of hospital admission compared to patients intervened within the first 4 days. Lefaivre et al.16 did not report this association, although they did agree that surgical delay was associated to a higher number of postoperative complications. Likewise, in a study reviewing 18,817 hip fractures, Holt et al.17 did not find an association between mortality and surgical delay. Among patients treated with anti-platelet drugs, Mas-Atance et al.9 reported that interventions conducted before 48h of hospital admission showed an increase of intraoperative bleeding, with no relevant clinical significance, whereas delay beyond the fifth day did not improve the clinical and analytical results and showed a trend toward increasing mortality. Maheshwari et al.8 found that surgical delay was the only predictive factor of mortality at 1 year of surgery in patients following antiaggregation treatment with clopidogrel. In our series, surgical delay was greater among patients with antiaggregation treatment, with no influence on mortality at 12 months or on a higher incidence of postoperative complications.

ASA grade was an adequate test of significant risk of death following hip fracture.18 In our study, 80% of patients with anti-platelets were ASA grade III–IV, compared to 27.7% of non anti-platelet patients. Medical stabilization of patients prior to surgery led to better conditions when facing an intervention, as well as a reduction of mortality during hospital admission and the immediate postoperative period. None of the patients in our series died during hospital admission and mortality at 3 months was similar between patients following anti-platelet treatment and those who were not. There was an association between ASA grade and mortality at 12 months in anti-platelet patients, as also reported by Navarrete et al.11 and by Lim et al.,12 although their patients were intervened in the first 48h.

Unlike ASA grade, the associated comorbidities reflected the health condition of patients. Among antiaggregation patients, 60% presented 3 or more associated comorbidities, compared to 42.1% in non antiaggregation subjects, and the mean number of associated comorbidities was higher among antiaggregation patients than among non antiaggregation patients. There was an association between the number of comorbidities and mortality at 12 months after the surgery, but not with the fact of presenting 3 or more associated comorbidities, as opposed to the report of Roche et al.,19 whose study noted that the presence of 3 or more comorbidities significantly increased mortality after 1 month among elderly patients.

The literature describes the determination of perioperative bleeding through formulas based on pre- and postoperative hematocrit and volemia. Mas-Atance et al.9 reported similar perioperative bleeding levels between non anti-platelet patients suffering proximal femoral fracture, anti-platelet patients intervened before 48h and anti-platelet patients intervened after the fifth day of admission. Our study presents limitations to determine perioperative bleeding, since the result of surgical drainages removed after 48h and preoperative hematocrit were not registered in a high percentage of cases. As indirect data, we did register the need for transfusion and the number of packed red blood cells transfused, which were similar in both groups.

The majority of anesthesiologists prefer to use spinal anesthesia, as long as it is not contraindicated, even though there is not enough scientific evidence regarding which anesthetic technique provides the best results in patients with hip fractures.3,20,21 In a study of 30 patients with proximal femoral fracture and anti-aggregant treatment with clopidogrel, Maheshwari et al.8 indicated that spinal anesthesia was a predictor of mortality at 12 months after the surgery in a univariate regression study. Mas-Atance et al.9 reported that general anesthesia was the norm among antiaggregation patients with proximal femoral fracture intervened before 48h; however, in cases where the surgery was delayed due to the anti-aggregant treatment, anesthesiologists clearly opted for locoregional procedures. In our series, all antiaggregation patients had a delay over 3 days and the anesthesiologist indicated spinal anesthesia in all cases.

Postoperative complications were similar in both groups (22% among antiaggregation patients and 15.6% in non antiaggregation patients), with no influence of ASA grade. In their series of antiaggregation patients treated with clopidogrel, Maheshwari et al.8 reported a rate of 43%, whilst Hossain et al.22 reported 8% in 50 patients with displaced subcapital femoral fracture treated through partial prosthesis in whom clopidogrel treatment was not interrupted.

The effect of treatment with ASA on the time of surgical intervention in patients with hip fracture did not increase intraoperative bleeding or the risk of subdural hematoma in cases with spinal anesthesia.3,23 Moreover, it should only be interrupted if the risk of hemorrhage was greater than the cardiovascular risk.24 For this reason, delaying surgery due to anti-aggregant treatment is not justified in patients treated with ASA. In our series, the mean surgical delay was similar between patients with no anti-platelets and anti-platelet patients treated with ASA. However, the percentage of patients with ASA grade III/IV was higher, which could justify the greater mortality observed at 12 months after the surgery.

Regarding the management of clopidogrel, there is a lack of consensus among patients with hip fracture.25–27 The Clinical Practice Guideline on the perioperative management of anti-platelet drugs in non-cardiac surgery published by SEDAR4 recommends interrupting treatment with clopidogrel between 3 and 7 days before an invasive procedure, although it indicates that recovery of hemostatic competence probably does not require a total elimination of the drug and that there is great variability between individuals regarding the grade of platelet inhibition. Hossain et al22 compared postoperative complications between 50 patients with displaced subcapital femoral fractures treated with partial prostheses in whom treatment with clopidogrel was not interrupted and 52 non anti-aggregation patients with the same type of fracture and treatment, and found no differences between both groups, although 88% of patients treated with clopidogrel required general anesthesia. In our series, taking into account the limitations of being a reduced group of cases to extract conclusions, these patients had a higher number of comorbidities, ASA grade and longer surgical delay, which could explain the fact that they presented the highest mortality at 12 months after the surgery out of the 3 groups.

ConclusionsIn our series, patients with anti-platelet treatment were older and presented a higher preoperative number of comorbidities, mainly cardiac, and ASA grade. Antiaggregation conditioned an extension in surgical delay and hospital admission. Taking into account the limitations of the present study, patients treated with anti-platelet drugs presented greater cumulative mortality at 12 months after surgery than cases with no anti-platelet treatment, with no increase in surgical and medical complications or in transfusion requirements being observed.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

FinancingThe authors declare that they have not received any financing to conduct the present study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Agudo Quiles M, Sanz-Reig J, Alcalá-Santaella Oria de Rueca R. Antiagregación en pacientes con fractura subcapital desplazada de fémur tratados con prótesis parcial cementada. Estudio de complicaciones y mortalidad. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:104–111.