Through percutaneous approaches, hallux valgus corrections can be performed with minimal soft tissue injury, postoperative pain, and good cosmetic results. Bosch osteotomy and MICA (Minimally Invasive Chevron Akin) have been shown to be effective techniques for the correction of hallux valgus, although there are currently no publications comparing percutaneous techniques with each other. The aim of this work is to compare the radiological and functional results of both techniques.

Materials and methodsA retrospective, comparative study was carried out on patients with moderate hallux valgus. They were divided into 2 groups according to the percutaneous technique used: chevron osteotomy and Bosch osteotomy with screw fixation. The metatarsophalangeal, intermetatarsal, and distal articular veneer declination angles of the first metatarsal and the bone consolidation time were evaluated radiologically. The American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Surgery (AOFAS) scale was used for functional assessment. Complications were collected during the first year.

ResultsThirty-eight patients in each group were included for the study. In each of the groups, the radiological angles were compared preoperatively and at the end of the follow-up, showing statistically significant changes in the 3 variables considered; but no differences were obtained by comparing them with each other. The time of consolidation was also similar in both groups. As for the AOFAS scale, an improvement was obtained with both techniques, but the difference was not significant when comparing them.

ConclusionsBoth Bosch and MICA techniques showed comparable results at the end of the monitoring. Further work is needed to determine the advantages of each in the immediate postoperative period.

A través de abordajes percutáneos se pueden realizar correcciones del hallux valgus con mínima lesión de partes blandas, dolor postoperatorio, y buenos resultados cosméticos. La osteotomía de Bosch y la MICA (Minimally Invasive Chevron Akin) han demostrado ser técnicas efectivas para la corrección del hallux valgus, si bien actualmente no existen publicaciones que comparen técnicas percutáneas entre sí. El objetivo de este trabajo es comparar los resultados radiológicos y funcionales de ambas técnicas.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo, comparativo en pacientes con hallux valgus moderado, se dividieron en 2 grupos según técnica percutánea utilizada: osteotomía en chevron y osteotomía de Bosch con fijación con un tornillo. Se evaluó radiológicamente ángulos metatarsofalángico, intermetatarsiano, de declinación de la carilla articular distal del 1er metatarsiano y el tiempo de consolidación ósea. Para la evaluación funcional se utilizó la escala de la American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Surgery (AOFAS). Se recogieron las complicaciones durante el primer año.

ResultadosSe incluyeron para el estudio 38 pacientes en cada grupo. En cada uno de los grupos se compararon los ángulos radiológicos en el preoperatorio y al final del seguimiento, mostrando cambios estadísticamente significativos en las 3 variables consideradas; pero no se obtuvieron diferencias comparándolas entre sí. El tiempo de consolidación también fue similar en ambos grupos. Y en cuanto a la escala AOFAS se obtuvo mejoría de la misma con ambas técnicas, no siendo significativa la diferencia al compararlas.

ConclusionesTanto de la técnica de Bosch como la MICA mostraron resultados comparables al final del seguimiento. Nuevos trabajos son necesarios para determinar las ventajas de cada una en el postoperatorio inmediato.

The choice of technique for the surgical treatment of hallux valgus is still widely discussed. Despite more than 200 procedures described, the choice of the best technique remains controversial.1 Today, with minimally invasive surgical techniques, corrections can be achieved through small incisions, with minimal damage to surrounding soft tissue, rapid recovery, and less scarring.2 Studies have already shown that certain distal osteotomies of the first metatarsal, open or percutaneous, can correct intermetatarsal angles of up to 20 degrees, correct distal articular veneer declination angles, and decrease metatarsophalangeal stiffness.3,4

The first-generation percutaneous hallux valgus correction was described by Isham,5 which had no fixation. The second generation was the technique described by Bösch,6,7 which has recently become popular due to its low technical demand and few complications. In this technique, a straight subcapital osteotomy of the first metatarsal is performed and temporarily fixed with a Kirschner wire. Several studies have shown good results,8–10 but the lack of stable fixation and early metatarsophalangeal mobilisation has been criticized.11,12 In this regard, in the third generation, procedures started to use more rigid fixations. The Minimally Invasive Chevron Akin (MICA) technique, described by Redfern and Vernois in 2011,13 uses two compression screws, dispensing with temporary K-wire stabilization. It also adds Akin's osteotomy in the proximal hallux phalanx, also stabilized with one screw. Similarly, other authors have combined the concepts of the Bösch osteotomy with internal fixation, adding a screw in addition to temporary K-wire fixation.14

Although there are papers that compare percutaneous techniques with open techniques,14–17 there are no publications as yet that compare percutaneous techniques with each other.

The objectives of this paper were to analyse and compare the functional and radiological results of two cohorts of patients with a diagnosis of moderate hallux valgus, one undergoing the percutaneous chevron technique, fixed with two screws without a temporary Kirschner wire; and the other the percutaneous Bösch osteotomy stabilized with a screw and a percutaneous Kirschner wire. Our hypothesis is that there are no clinical or radiographic differences between the two techniques at one year of follow-up.

Material and methodWe undertook a comparative study of two retrospective series of patients, for whom percutaneous surgery was indicated to correct moderate hallux valgus, using two techniques: one with percutaneous chevron osteotomy, without Akin osteotomy, adding tenotomy of the adductor tendon of the hallux; and the other with percutaneous Bösch osteotomy, modified with fixation with a screw and adductor tenotomy.

Approval was obtained from the institution's Ethics Committee for Research Protocols, and the confidentiality of the patients included in the study was respected at all times.

Inclusion criteriaAdult patients were included in the study, over 21 years old, with a diagnosis of moderate hallux valgus, this being defined as intermetatarsal angles between 11°-16° and metatarsophalangeal angles of 20°-40°.18

Exclusion criteriaPatients were excluded if they had undergone an additional procedure to their forefoot, had a history of previous surgeries, had presented previous metatarsal pain, or had not completed follow-up at one year following surgery.

Study variablesThe American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Surgery (AOFAS) scale19 was used for functional assessment before surgery and at the end of follow-up.

For the radiological study, weightbearing X-rays were taken of both feet in anteroposterior and lateral projections, preoperatively and postoperatively. We analysed and compared metatarsophalangeal angles (MPA), the intermetatarsal angle between the first and second metatarsals (IMA), and the distal articular veneer declination angles of the first metatarsal (DMAA).

The radiological bone consolidation time was evaluated, defining consolidation as the presence of bone bridges in a cortex in two radiological projections.20,21

Complications were recorded during the first year of follow-up.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are expressed as means with respective standard deviations. Categorical variables are expressed as relative or absolute frequencies.

A t-test was used for paired samples for the comparison of pre- and post-operative data, according to the type of osteotomy.

A t-test for independent samples was used for the comparison of data between osteotomies.

A power calculation was made considering a power of 80% and a precision of 95%.

A p value of less than 0.05 is considered significant.

STATA® software (StataCorp. 2017) was used for the statistical analysis. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

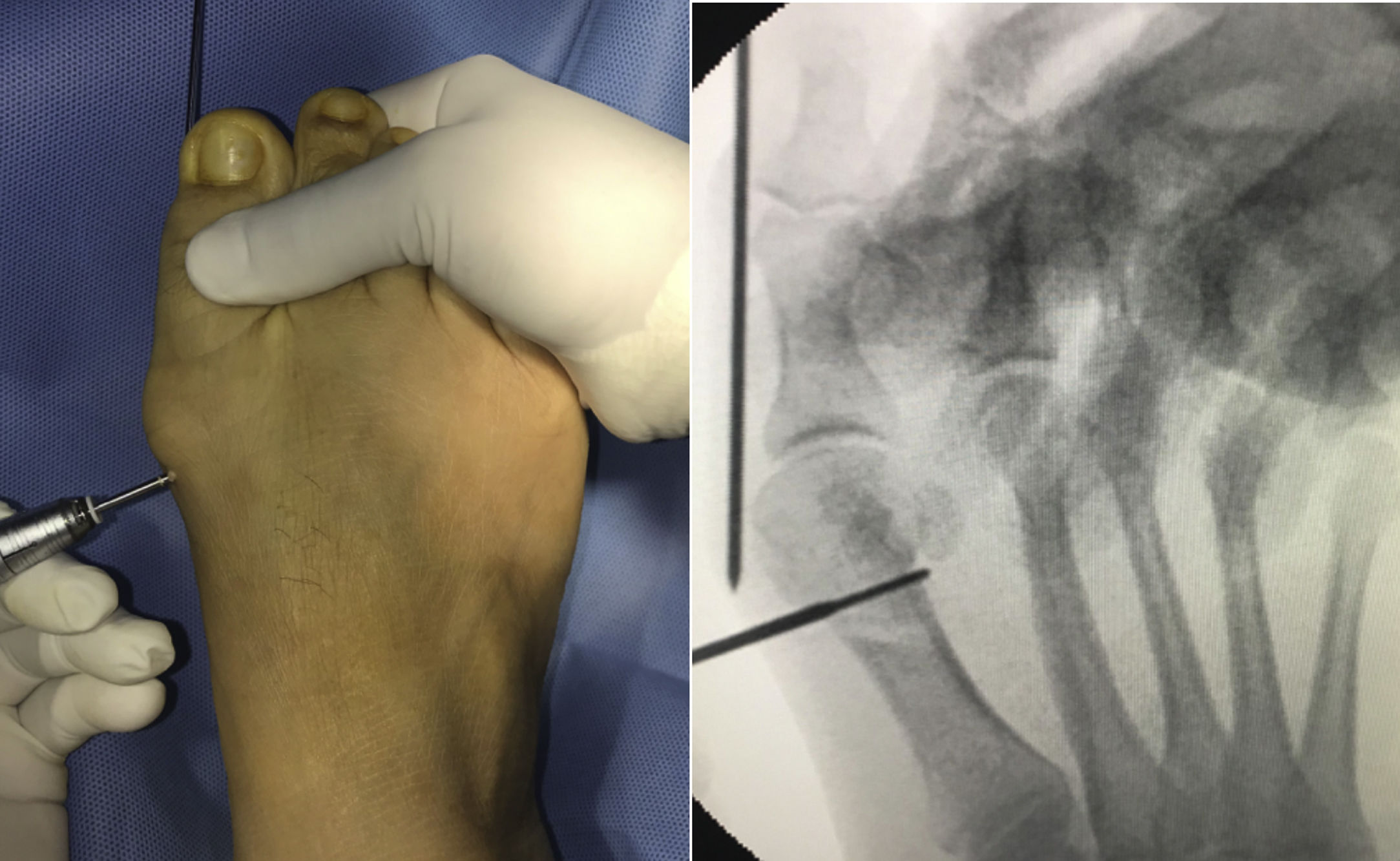

Surgical technique for percutaneous chevron osteotomyThe procedure is performed under regional anaesthesia, by means of ultrasound-guided selective block in the ankle.

A 2 mm subcutaneous medial Kirschner wire is introduced from the distal end of the hallux in a retrograde manner to the site where the osteotomy will be performed, in the first metatarsal neck.

Through a 3 mm medial incision, the osteotomy is performed with a 2 mm x 15 mm Shannon bur at the transition from the neck and head of the first metatarsal. The cut is initiated through an initial canal parallel to the distal articular surface on the metatarsal neck, which will serve as the "v" axis and then the dorsal and plantar branches are completed.

Lateral displacement of the head is performed, introducing the intramedullary K-wire from the area of the osteotomy with the help of a grooved probe.

The osteotomy is fixed percutaneously with two compression screws from proximal to distal towards the metatarsal head. It should be noted that the proximal screw is the first placed, and this should pass through three cortices through the osteotomy for better screw fixation (Fig. 1).

The adductor tendon is then released percutaneously. The Kirschner wire is removed and a varus correction bandage is applied.

The procedure is monitored by radioscopy.

Weightbearing is allowed immediately with a flat and rigid-soled post-operative shoe; weekly dressings are performed for three weeks and metatarsophalangeal joint mobilisation of the hallux starts from the second week.

Modified bösch osteotomy surgical techniqueUnder the same conditions as described above, in the Bösch osteotomy using a medial approach, a straight cut is made parallel to the distal joint veneer of the metatarsal at neck level. The wire is advanced in the same way as in the chevron osteotomy in the medullary canal for lateral cephalic displacement.

It is fixed with a screw from proximal towards the head and from medial to lateral, and the K-wire is maintained (Fig. 2). Percutaneous release of the hallux adductor tendon is performed.

Walking in a post-operative shoe with immediate weightbearing is also allowed. Weekly dressings are prescribed and the Kirschner wire is removed in the clinic in the third post-operative week (Figs. 3 and 4).

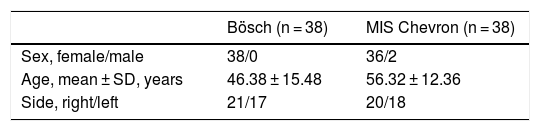

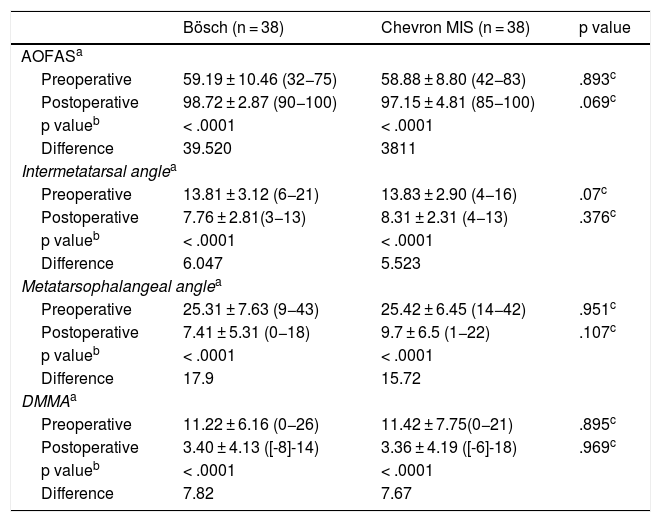

ResultsThirty-eight patients who underwent hallux valgus surgery using the percutaneous chevron technique with release of the adductor tendon (Chevron group) and 38 patients who underwent the Bösch technique (Bösch group) were included in the study between January 2016 and January 2017. The demographic data are shown in Table 1.

The average follow-up time was 12.39 months (SD 1.10) and 16.81 months (SD 8.97) respectively.

The radiological angles of each group were compared preoperatively (Pre) and at the end of follow-up (Pop) (Table 2). In the percutaneous chevron osteotomy group statistically significant changes were shown in the three variables considered, the means being: MPA pre: 25.42 (SD 6.45), pop: 9.7 (SD 6.5), p < .0001; IMA pre: 13.83 (SD 2.90), pop: 8.31 (SD 2.31), p < .0001; DMAA pre: 11.42 (SD 7.75), pop: 3.36 (SD 4.19).

Clinical and radiological outcomes.

| Bösch (n = 38) | Chevron MIS (n = 38) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOFASa | |||

| Preoperative | 59.19 ± 10.46 (32−75) | 58.88 ± 8.80 (42−83) | .893c |

| Postoperative | 98.72 ± 2.87 (90−100) | 97.15 ± 4.81 (85−100) | .069c |

| p valueb | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Difference | 39.520 | 3811 | |

| Intermetatarsal anglea | |||

| Preoperative | 13.81 ± 3.12 (6−21) | 13.83 ± 2.90 (4−16) | .07c |

| Postoperative | 7.76 ± 2.81(3−13) | 8.31 ± 2.31 (4−13) | .376c |

| p valueb | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Difference | 6.047 | 5.523 | |

| Metatarsophalangeal anglea | |||

| Preoperative | 25.31 ± 7.63 (9−43) | 25.42 ± 6.45 (14−42) | .951c |

| Postoperative | 7.41 ± 5.31 (0−18) | 9.7 ± 6.5 (1−22) | .107c |

| p valueb | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Difference | 17.9 | 15.72 | |

| DMMAa | |||

| Preoperative | 11.22 ± 6.16 (0−26) | 11.42 ± 7.75(0−21) | .895c |

| Postoperative | 3.40 ± 4.13 ([-8]-14) | 3.36 ± 4.19 ([-6]-18) | .969c |

| p valueb | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Difference | 7.82 | 7.67 | |

Bösch: Bösch osteotomy; MIS Chevron: Percutaneous Chevron osteotomy.

In the Bösch osteotomy group they also presented statistically significant correlations: MPA pre: 25.31 (SD 7.63), pop: 7.41 (SD 5.31), p < .0001; IMA pre: 13.81 (SD 3.12), pop: 7.76 (SD 2.81), p < 0.0001; DMAA pre: 11.22 (SD 6.16), pop: 3.40 (SD 4.13), p < .0001.

The mean consolidation time was 13.36 weeks for the chevron osteotomy group (SD 3.03), and 13.60 weeks for the Bösch osteotomy group (SD 2.43), the difference between both groups not being significant (p > .10).

The AOFAS scale showed an increase in mean values from 58.88 (SD 8.80) to 97.15 (SD 4.81) at 12 months (p < .0001) for the percutaneous chevron osteotomy, and from 59.19 (SD 10.46) to 98.72 (SD 2.87) (p < 0.0001) for the Bösch osteotomy.

In the comparative analysis between both techniques, no significant differences were demonstrated in terms of radiological angular corrections or on the AOFAS scale.

Among the complications in the percutaneous chevron osteotomy group were two superficial infections that were resolved with oral antibiotic treatment: an asymptomatic screw break and a screw extraction due to implant discomfort. Metatarsalgia was recorded in five patients (13.15%), absent before surgery, and one patient presented a stress fracture of the fourth metatarsal. There was a loss of osteotomy correction in the first week in only one case that had to be re-operated.

In the Bösch osteotomy group, one patient developed transfer metatarsalgia, there were two cases of delayed consolidation at five months, and two patients were re-operated: one to remove the screw due to discomfort from the implant, and another due to loss of osteotomy correction.

DiscussionThere is currently great interest in percutaneous forefoot surgery, due to the promising results published.2,22 However, the best technique has not yet been determined. Nor have any studies been published comparing percutaneous techniques with each other, beyond systematic reviews.23 In the present study we have analysed and then compared two percutaneous distal metaphyseal osteotomies. Both procedures achieved significant radiological correction and improvements in functional scales at the end of follow-up. We did not obtain differences in functional and radiological results between the techniques in the time analysed.

The published series referring to the Bösch technique show good results, with a low rate of complications and relapses.2,9,24–26 The lack of internal fixation in this second generation technique makes it necessary to maintain the Kirschner wire for four to six weeks, which prevents early joint mobility of the hallux and increases the risk of skin complications and the possibility of loss of correction and displacement of the head of the first metatarsal.6

Thus, the Bösch osteotomy was modified by adding a screw for osteotomy fixation, allowing the wire to be removed in the third week.14 We found no published series with this technique, although in the paper by Brogan, fixation is performed with a single screw and wire for three weeks, and the cut is made in chevron, as in MICA. We obtained good results, comparable to those published with the original technique, and therefore we can conclude that the placement of a cephalic screw in the Bösch osteotomy reduces the time of immobilization with the wire, providing greater comfort to the patient and avoiding the possible complications mentioned.

In the MICA13,27 technique a more stable cut is generated, and the rigidity of the fixation is increased with the placement of two screws, avoiding the need for temporary fixation with wires. Several authors have published series with this technique and its modifications.15,17 The most extensive patient series published with the MICA technique is that of Jowett and Bedi,28 which includes 106 feet, with a follow-up of 25 months, and the results reported are comparable to our series.

The MICA technique29 describers explain that the decision to add an Akin osteotomy or adductor tendon tenotomy depends on the deformity remaining after metatarsal osteotomy. Neither the original paper nor the other published series13,15,17,28 establish objective criteria for adding any of these procedures. Systematically performing an Akin osteotomy would increase morbidity, pain, possible complications, surgical time, and cost. Percutaneous adductor tenotomy adds soft tissue dependent correction, involves little time, and avoids the need for implants. In our paper we performed the tenotomy in both groups, but we know that there are no guidelines for its indication either and that it should be analysed in future studies.

Regarding complications, we reported the presence of transfer metatarsalgia in five cases in the chevron osteotomy and one in the Bösch osteotomy. This may be due to the shortening generated by the cutting bur when the osteotomy is performed, although shortening of the first radius may encourage reduced stiffness of the metatarsophalangeal joint.3

In our paper we did not obtain differences in functional and radiological outcomes with either technique in the time analysed. It seems that the early mobilisation of the hallux in the percutaneous chevron technique would avoid stiffness,3 although this variable has not been examined in our study. As disadvantages of this technique we consider that the percutaneous chevron cut is more demanding than performing a straight cut and may increase surgical time. However, for surgeons experienced in percutaneous surgery it should not present difficulties.28 As a second point to consider, the placement of a second screw increases surgical costs. The choice should be based on the surgeon's experience in percutaneous surgery and the patient's economic means.

As a weakness of the study, we consider that since it is a retrospective series, the differences between the two techniques were not evaluated in the early postoperative period. Prospective comparative studies are necessary to establish immediate differences, as it is in that period when differences between both techniques can be found. In addition, long-term differences in terms of arthritic changes and joint mobility should be studied in future studies.

ConclusionsThe modified Bösch and chevron percutaneous techniques were effective for the percutaneous correction of hallux valgus, with similar results to each other in the long term. Studies with a better level of evidence are necessary to determine outcomes not only in the long term, but also in the immediate postoperative period, since differences between the techniques can be observed over that period.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe authors declare that no animal testing was performed. They also state that the research study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Research Protocols of the Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires and that the patients signed their informed consent.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

FundingThis research received no specific grants from public sector agencies, commercial sector agencies or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Carlucci S, Santini-Araujo MG, Conti LA, Villena DS, Parise AC, Carrasco NM, et al. Cirugía percutánea para hallux valgus: comparación entre osteotomía en chevron y de Bosch. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:401–408.