To evaluate whether postoperative continuous wound infiltration of levobupivacaine through two submuscular catheters connected to two elastomeric pumps after lumbar instrumented arthrodesis is more effective than intravenous patient-controlled analgesia.

Material and methodsAn observational, prospective cohorts study was carried out. The visual analogue scale, the need for additional rescue analgesia and the onset of adverse effects were recorded.

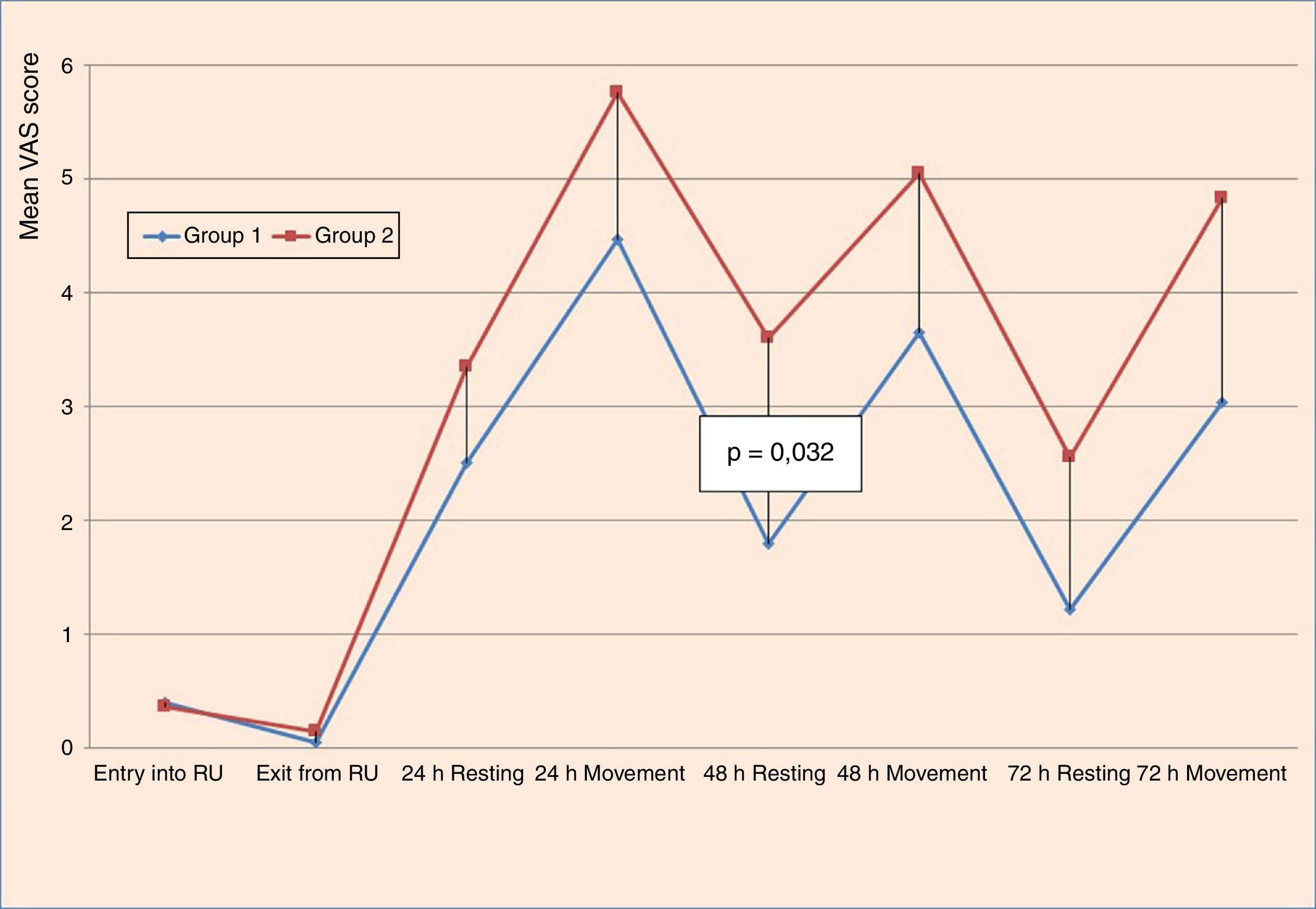

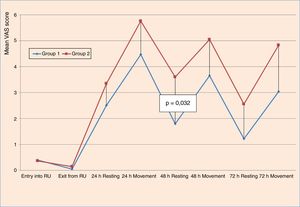

ResultsPain records measured with visual analogue scale were significantly lower in the 48h postoperative record at rest (p=.032). The other records of visual analogue scale showed a clear tendency to lower levels of pain in the group treated with the catheters. No statistically significant differences were found in the rescue analgesia demands of the patients. The adverse effects were lower in the catheter group (6 cases versus 11 cases) but without statistical differences.

ConclusionsA trend to lower pain records was found in the group treated with catheters, although differences were not statistically significant.

Valorar si la administración asociada de levobupivacaína a través de dos catéteres percutáneos submusculares conectados a dos bombas elastoméricas en el postoperatorio de la artrodesis instrumentada lumbar es más eficaz que el uso aislado de analgesia intravenosa controlada por el paciente con cloruro mórfico y comparar sus efectos secundarios.

Material y métodoEstudio observacional, prospectivo, de cohortes. Se comparó la necesidad de analgesia de rescate entre ambos grupos, la valoración subjetiva del dolor mediante la escala visual analógica y la presencia de efectos adversos con una y otra técnica.

ResultadosNo se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en cuanto a las necesidades de analgesia de rescate. El dolor medido con la escala visual analógica fue significativamente menor (p = 0,032) en reposo a las 48h postoperatorias en el grupo tratado con catéteres. La escala visual analógica media en el resto de momentos presentó una tendencia a un menor dolor postoperatorio en el grupo tratado con catéteres, pero sin significación estadística. No hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en los efectos adversos, aunque en el grupo tratado con catéteres hubo 6 casos de efectos adversos frente a 11 casos del grupo tratado con analgesia convencional.

ConclusionesSe observó una tendencia en el grupo tratado con catéteres a presentar menor dolor postoperatorio con menos efectos indeseables, aunque las diferencias no fueron estadísticamente significativas.

Inherent tissue injury is present in surgical procedures and leads to postoperative pain,1 the control of which is essential for reducing morbidity in our patients.

Acute postoperative pain after spine surgery is an adverse clinical effect which impairs outcomes in different aspects.2,3 Delayed mobility also adds to the development of medical complications such as venous thromboembolic disease, paralytic ileus or aspiration pneumonia. The limitation of movement delays rehabilitating treatment and impedes autonomous walking. Inappropriate pain management leads to lower satisfaction, greater psychological distress and leads to the development of chronic pain. Finally, this all leads to a prolongation of hospital stay and possibly raised costs.2,4,5 Satisfactory analgesia is thus not only important from a clinical viewpoint but also from a financial one.

Consensus therefore exists that appropriate treatment of acute postoperative pain improves the outcome of the surgical procedure and as a result advanced techniques on analgesia have been developed which have been demonstrated to be effective.5,6 At present information is needed on how to protocolise these techniques, associating them with other anaesthetic modalities in the different surgical procedures.

The purpose of this study was to assess whether the administration of levobupivacaine through two submuscular catheters connected to two elastomeric pumps in the post-operative period after lumbar instrumented arthrodesis reduces postoperative pain during the first 72h and compare its efficacy with patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCA-IV). We also studied its side effects and complications, when use was prolonged over 72h and its possible effects on postoperative recovery.

Material and methodsAn observational, prospective, cohort study was carried out in our healthcare area with patients who had undergone lumbar instrumented arthrodesis in our hospital between 2009 and 2013. The patients were part of the prospective record of data on postoperative pain from the Acute Pain Unit of the Anaesthesiology, Intensive Care and Pain Therapy Service.

Inclusion criteria were for patients aged 18–85 years who had been diagnosed with degenerative lumbar discopathy or stenosis of the lumbar canal and who had undergone a lumbar instrumented arthrodesis from behind using a posterolateral technique or transforaminal interbody fusion (TLIF), belonging to Groups 1–3 on the assessment scale of the American Society of Anaesthesiology and with a follow-up documented from the immediate postoperative period in the Reanimation Unit (RU).

Patients were divided into two cohorts depending on the analgesic technique carried out in each of them. The first cohort (Group 1) received treatment with two submuscular catheters connected to two elastomeric pumps of 0.25% levobupivacaine at an infusion rate of 5ml/h, which was inserted on termination of surgery by the surgeon (Painfusor system. Baxter International Inc. Deerfield, Illinois). This treatment was added to a treatment of PCA-IV of morphine associated with a combined intravenous (IV) analgesia of dexketoprofen (50mg/8h) and paracetamol (1g/8h), using 50mg of IV tramadol as rescue analgesia which was patient-controlled. The PCA pump had a continuous morphine infusion and the patient could self-administer a number of prefixed additional boluses. When the self-administration of the patient surpassed certain parameters of time and prefixed doses in the pump, the clicks did not produce effective boluses, and this was a security measure to prevent overdosing. On analysis, the ineffective boluses and the demand and administration of IV tramadol to the patient were considered and analysed as “need for rescue analgesia”. For this study the “effective boluses” were not considered since we know that they are related to specific moments, such as movements made by the auxiliaries and nurses on the ward for washing and curing and often it is the healthcare staff who tell the patient to receive a bolus prior to carrying out these procedures. The second cohort (Group 2) received the same analgesic treatment, with the same PCA-IV parameters, the same combined analgesia and the same opportunity for rescue therapy, but without the two catheters. All the patients of both groups were operated on by the same surgeon; the decision to insert the catheters was suggested by the anaesthetists from the acute pain unit who were responsible for follow-up and control of the postoperative analgesia.

The catheters used by the patients of Group 1 have a perforated tip and a multi-perforated distal area with several sizes which vary between 7.5 and 15cm in length along the perforated area (counted from the tip). This means that the infusion of the anaesthetic covers a larger incision area. They are inserted using a long, plastic-coated needle which acts as a temporary guarantor. The catheter is inserted through this after removing the metallic needle, and in our study this was always prior to closing the surgical wound, so as to place it in the desired region: usually on the laminae or laterally to them when a decompressive laminectomy had been performed. After this the skin was attached with adhesive paper strips and transparent dressings. The recharged elastomeric pumps with the local anaesthetic begin to be used immediately prior to the patient leaving the operating theatre (Fig. 1). The catheters are inserted on termination of the operation through two punctures made in the skin close to the surgical incision and are removed after 72h, in keeping with protocol.

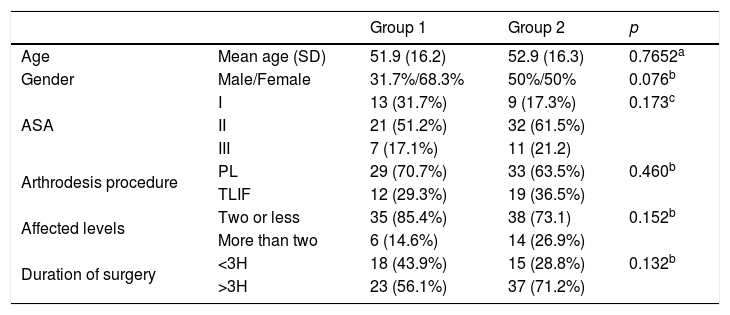

Patients who did not complete follow-up during the first 72h were excluded. The total sample comprised 93 patients, who were divided into 41 for Group 1 and 52 for Group 2. Both groups were comparable (Table 1).

Cohort characteristics.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean age (SD) | 51.9 (16.2) | 52.9 (16.3) | 0.7652a |

| Gender | Male/Female | 31.7%/68.3% | 50%/50% | 0.076b |

| ASA | I | 13 (31.7%) | 9 (17.3%) | 0.173c |

| II | 21 (51.2%) | 32 (61.5%) | ||

| III | 7 (17.1%) | 11 (21.2) | ||

| Arthrodesis procedure | PL | 29 (70.7%) | 33 (63.5%) | 0.460b |

| TLIF | 12 (29.3%) | 19 (36.5%) | ||

| Affected levels | Two or less | 35 (85.4%) | 38 (73.1) | 0.152b |

| More than two | 6 (14.6%) | 14 (26.9%) | ||

| Duration of surgery | <3H | 18 (43.9%) | 15 (28.8%) | 0.132b |

| >3H | 23 (56.1%) | 37 (71.2%) |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiology; SD: standard deviation; PL: posterolateral; TLIF: transforaminal interbody fusion.

The need for rescue analgesics was studied in each group, together with the intensity of postoperative pain when resting and in movement according to the VAS scale (with 0 as absence of pain and 10 as the worst pain imaginable) and the adverse effects of treatment. The latter referred to the presence or absence of changes in the respiratory pattern, sedation, nausea, itching or retention of urine. The scores were assessed at four times: the immediate postoperative period in the RU, and 24, 48 and 72h after surgery. The frequency with which prolonged treatment over 72h was required was also assessed.

Data analysis and the statistical study were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 programme (IBM Inc., Armonk, USA). The Chi-squared test was used (χ2) with a 95% confidence interval and significance level of 5% (p<.05) for the study of the need for rescue analgesia and of adverse effects. The study of VAS scale scores was made with the non parametric Mann–Whitney U test, with an acceptable significance of 5% (p<.05).

ResultsThree patients from Group 1 (7.3%) and 7 patients from Group 2 (13.4%) required rescue analgesia immediately after surgery (p=.342). After 24h 6 patients from Group 1 (14.6%) needed it and 5 patients from Group 2 (9.6%) (p=.457). After 48h, 3 patients from Group 1 (7.5%) and one patient from Group 2 (1.9%) (p=.193) needed it. Finally, after 72h, one patient from Group 1 (3.5%) and one patient from Group 2 (2.5%) (p=.817) needed it. There were no statistically significant differences in any of the four moments assessed regarding the need for rescue analgesia between the two groups.

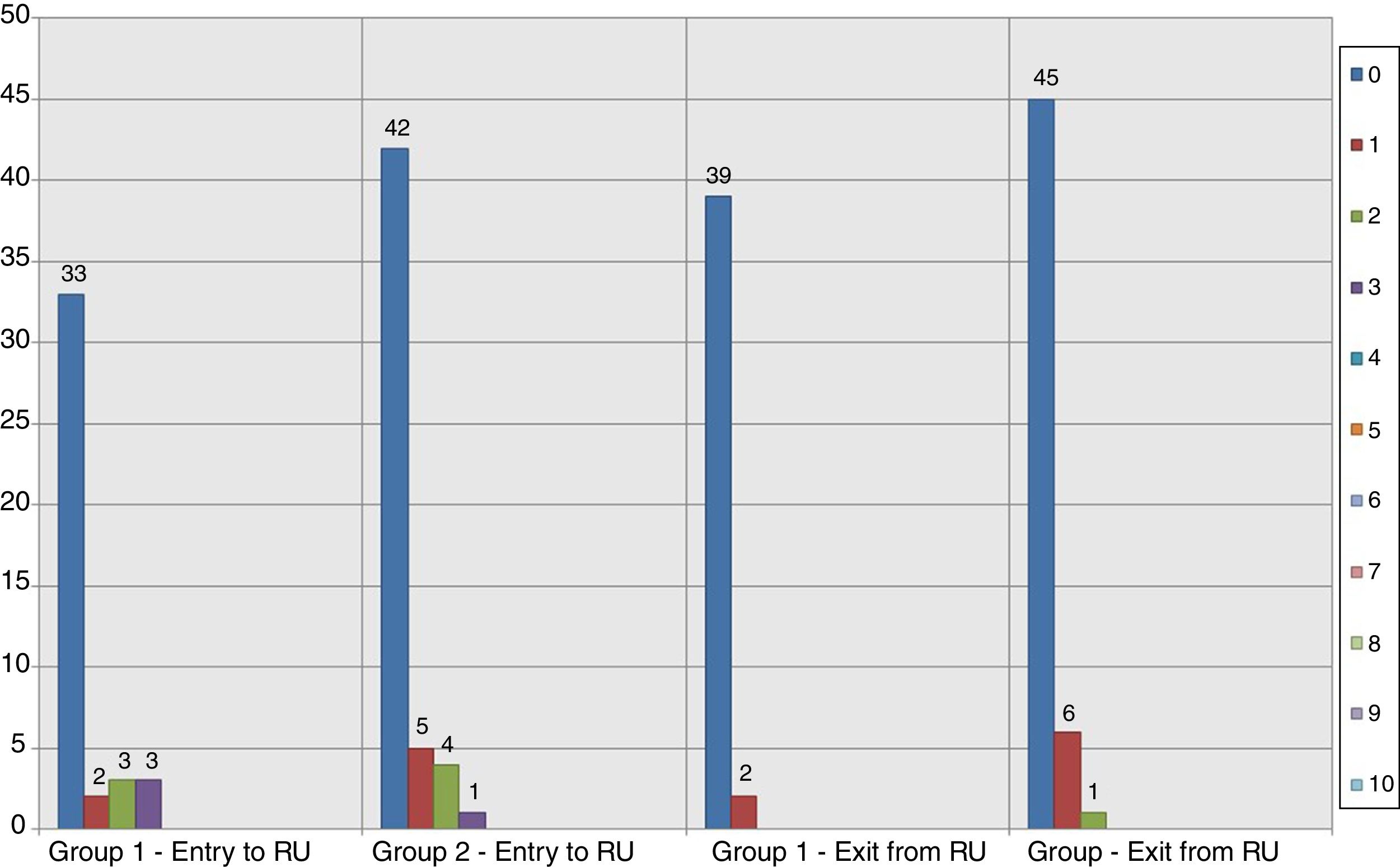

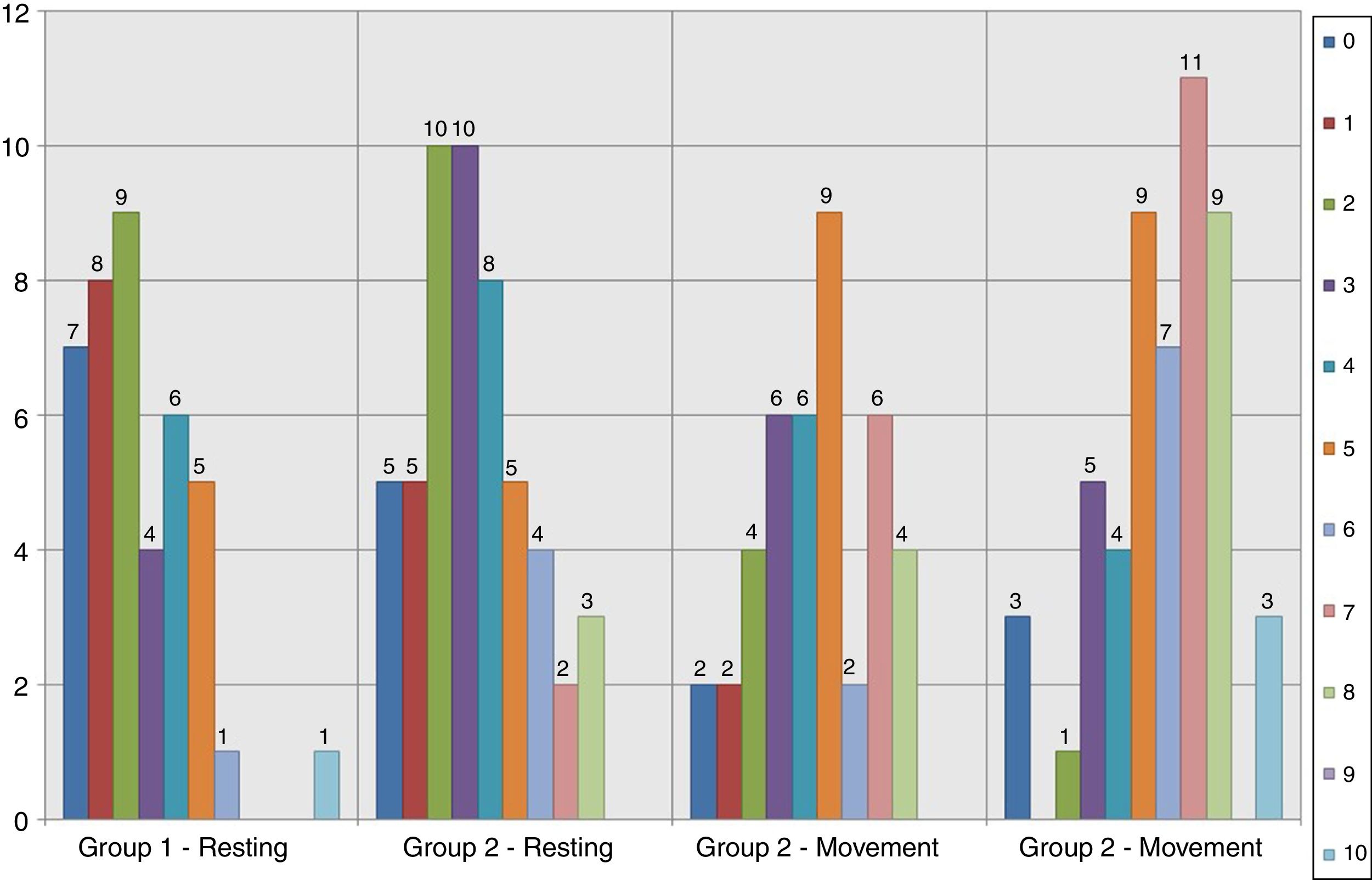

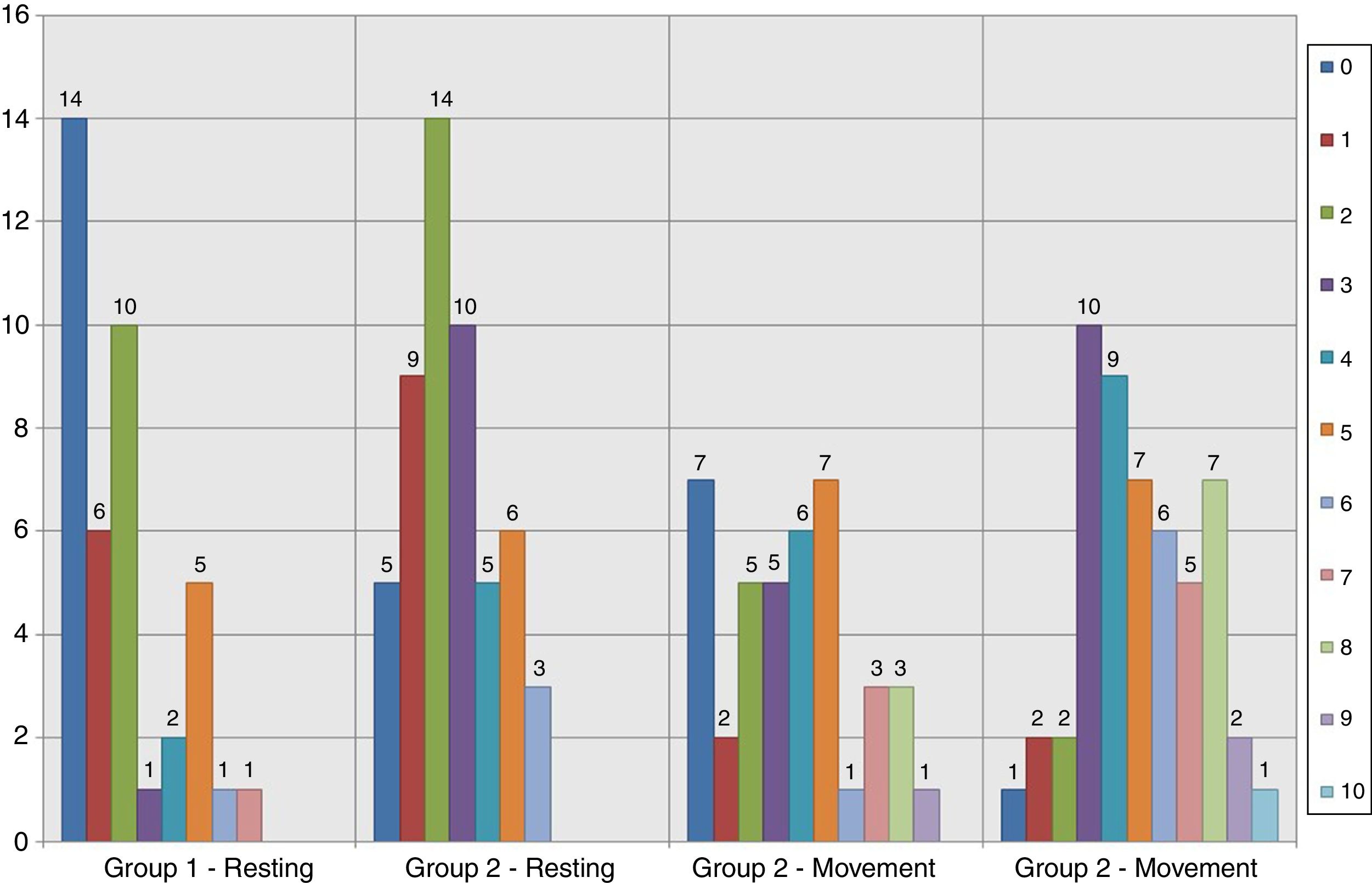

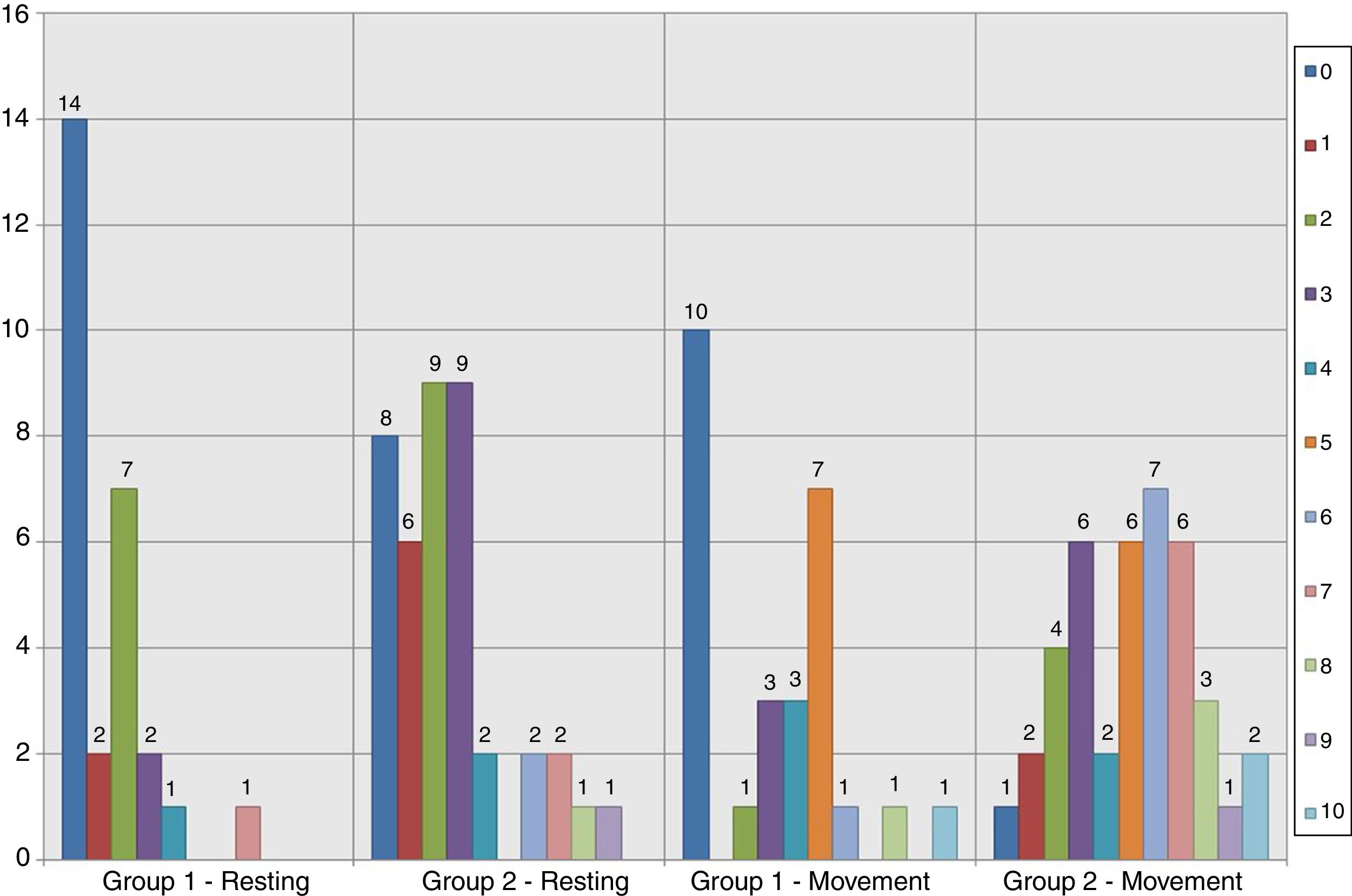

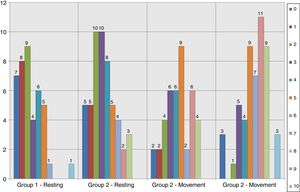

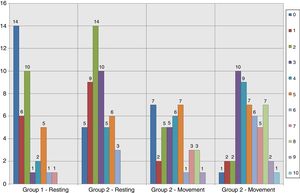

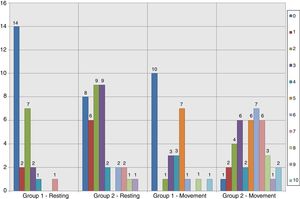

Results relating to pain according to the VAS scale on entry and exit from the RU in the study groups are shown in Figs. 2–5. There were statistically significant differences with less pain in Group 1, in the distribution of VAS values after 48h (p=.032) (Figs. 4–6). Regarding the mean score of the VAS scale values, there was a clear tendency for a more effective analgesia in Group 1, although without any statistical significance during the other times of measurement (Fig. 6).

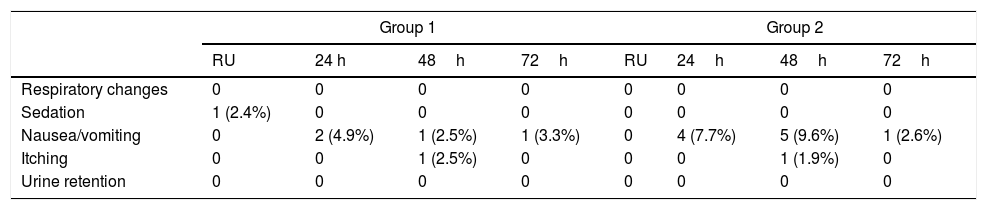

There were few adverse effects to medication, which made their statistical analysis complex (Table 2). In the RU there was one case of sedation in Group 1, compared with none in Group 2. During the first 24h there were 2 cases of nausea in Group 1, compared with 4 in Group 2. On day two one case of nausea was recorded and one of itching in Group 1, compared with 5 cases of nausea and one of itching in Group 2. After 72h there was one case of nausea in Group 1 and another in Group 2. No statistically significant differences were found in the presentation of side effects when comparing them day by day. Grouping all the cases of nausea (the most common side effect) from Group 1 (4 cases) and Group 2 (10 cases in the three days) no significant difference was detected (p=.207), although the tendency indicated a minor incidence of adverse effects in the group treated with sub muscular catheters.

Presence of adverse effects. In the boxes where an adverse effect has occurred the percentage of cases is indicated with respect to the total of that group.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RU | 24 h | 48h | 72h | RU | 24h | 48h | 72h | |

| Respiratory changes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sedation | 1 (2.4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0 | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0 | 4 (7.7%) | 5 (9.6%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Itching | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.9%) | 0 |

| Urine retention | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

One patient from Groups 1 and 3 patients from Group 2 had to continue pain control by the Acute Pain Unit beyond the 72 postoperative hours (p=.431).

DiscussionAlthough the importance of postoperative pain control is well known it has been estimated that 30–86% of patients who have undergone surgery presented with moderate or serious pain despite advanced anaesthesia techniques having been developed.3

Instrumented lumbar arthrodesis is a common surgical procedure which may be associated with major pain in the postoperative period. If it is not satisfactorily controlled it may lead to additional medical comorbidities and suffering by the patient.

There is no ideal analgesic modality although there are several different treatment strategies, most of which may be replaced by oral analgesics 72h after surgery. An intradural anaesthesia may be carried out to control pain during surgery and immediately after it. In some of the oldest publications it was chosen to perform specific infiltrations of the musculature and/or on the subcutaneous plane when closing the surgical wound, generally in small incisions.7–9 Another possibility was to perform surgery with a general anaesthesia and to add epidural or intradural opioids during the procedure. However, acute postoperative pain usually lasts over several days, when the effect of the opiod has waned. The use of PCA-IV with opioids associated with systemic NSAIDS is the treatment of choice at our hospital. This consists of the continuous infusion of a prefixed dose of analgesic which the patient self-administers, depending on pain level, in small doses of additional intravenous opioid during the postoperative period. Another analgesic modality consists of the continuous administration of opiods or local analgesics through an epidural catheter before or during surgery.6

Studies exist which compare the use of the continue epidural catheter with the PCA-IV of morphine but no significant differences have been demonstrated regarding pain intensity reduction or in changes in the adverse effects which arise.10 The epidural catheter may administer local anaesthetics alone or associated with opiods, and there are references to this in scoliosis surgery.10,11 The main drawback of epidural analgesia with local anaesthetics is that it may impede neurological assessment and delay the diagnosis of possible complications to surgery. However, they expose the patient to haematomas or infections,12 and this usually discourages the spine surgeon from using them.

Continuous infiltration of the surgical wound with local anaesthesia to modulate peripheral transmission of pain is another possibility.7 The technique is used in surgical interventions with painful postoperative periods, such as major abdominal or caesarean surgery.13,14 It has also been used in orthopaedic procedures with favourable results compared with placebo,15–18 and has been suggested for spine surgery.19 Infiltration of the surgical wound is an easy analgesic modality to perform. It is simple, safe, cheap and has few complications lasting beyond the first 2–3 days after surgery, when pain is most intense.20 Local anaesthetics are the main agents employed through infiltration catheters for the surgical wound since they block the conduction, nerves and reduce inflammation due to their anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties.21 In our study we found no major local complications in the group where the continuous infusion technique was used. This safety was also contrasted in other procedures and locations.22 The main drawback of infiltration techniques of the surgical wound is that they do not block deep structures, and are therefore only recommended for minor incisions and in subcutaneous administration. For higher efficacy in sensitive blocking at deeper levels the use of submuscular catheters may be suggested in the space between the musculature dissected during surgery and the vertebral laminae.23,24

Current research aims at determining how to introduce these techniques within the multimodal protocols of postoperative pain treatment for each pathology or procedure.25,26 In our study we observed that the patients with continuous infiltration of the surgical wound with local anaesthetics hardly required rescue analgesia, although neither did those who belonged to the group considered the control group. Reduction of pain on the VAS scale revealed a tendency towards a higher analgesic response in Group 1, as others had also reported.19,23,27 The adverse effects which were recorded in our series were reduced, and there was a lower rate of nausea, which is the main secondary effect that occurs in treatments with opioids. Although there were no statistically significant differences, in Group 1 side effects occurred in 4.9% of cases during the first day and in 2.5% of cases during the second day, compared with 7.7% and 9.6% in Group 2. This was all associated with a lower consumption of opioids in the cases with PCA-IV, which led to a faster recovery in the patients.28 It has been the use of combined analgesia techniques for many years, or multimodal analgesia which has led to an increase in the perceived quality of the analgesia by the patient and also to a saving of opioids and reduction in side effects.4,6,13

The main limitations of our study include the fact that it is observational and with a relatively small sample (n=93). Learning to insert the catheter was not a limitation because the nursing staff had been instructed in handling this in previous cases, prior to the start of selecting patients for the study.

Another point to consider is an awareness of optimum administration doses and flow and which catheters are the most appropriate.29 in our study the benefit found by association of therapies is relative and one of the reasons may be the complete dose of anaesthetic, the rate of infusion or even the type of catheter used. There is no definitive recommendation on these aspects of treatment, but it has been clarified that the plasmatic concentrations achieved with this type of therapy are limited and the possibility of systemic complications are low.30

To conclude in our work, continuous infiltration of the surgical wound with local anaesthetic has a tendency to reduce postoperative pain in patients with instrumented lumbar arthrodesis, with fewer side effects but there continues to be a lack of sufficient scientific evidence. With regard to the observed tendency in our study, and the existing references, it would appear recommendable to carry out new studies to resolve this controversy.

Level of evidenceProspective cohort study. Level of evidence 2b.

Ethical disclosureProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were carried out on humans or animals for this research study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare they have followed the protocols of their centre of work on patient data publication.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ortega-García FJ, García-del-Pino I, Auñon-Martín I, Carrascosa-Fernández AJ. Utilidad de los catéteres percutáneos para perfusión continua de anestésico local en el manejo del dolor postoperatorio en pacientes sometidos a artrodesis lumbar instrumentada. Estudio de cohortes prospectivas. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:365–372.