To carry out a statistical analysis on the significant risk factors for deep late infection (prosthetic joint infection, PJI) in patients with a knee arthroplasty (TKA).

MethodsA retrospective observational case–control study was conducted on a case series of 32 consecutive knee infections, using an analysis of all the risk factors reported in the literature. A control series of 100 randomly selected patients operated in the same Department of a University General Hospital during the same period of time, with no sign of deep infection in their knee arthroplasty during follow-up. Statistical comparisons were made using Pearson for qualitative and ANOVA for quantitative variables.

ResultsThe significant (p>0.05) factors found in the series were: preoperative previous knee surgery, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, inflammatory arthritis.

Intraoperative prolonged surgical time, inadequate antibiotic prophylaxis, intraoperative fractures. Postoperative secretion of the wound longer than 10 days, deep palpable hematoma, need for a new surgery, and deep venous thrombosis in lower limbs. Distant infections cutaneous, generalized sepsis, urinary tract, pneumonia, abdominal.

ConclusionsThis is the first report of intraoperative fractures and deep venous thrombosis as significantly more frequent factors in infected TKAs. Other previously described risk factors for TKA PJI are also confirmed.

Describir los factores de riesgo estadísticamente significativos para la infección periprotésica tardía (PJI, «prosthetic joint infection») en rodilla.

Material y métodoEstudio observacional y retrospectivo mediante comparación de series de casos y controles. Se han analizado todos los factores de riesgo descritos en la literatura. Casos: 32 prótesis de rodilla infectadas diagnosticadas consecutivamente. Controles: 100 pacientes seleccionados aleatoriamente, intervenidos quirúrgicamente en el mismo servicio de un hospital general universitario durante el mismo período de tiempo, sin signo alguno de infección a lo largo de todo el seguimiento. Comparaciones estadísticas: Pearson para variables cualitativas y ANOVA para cuantitativas.

ResultadosLos siguientes hechos son significativamente más frecuentes (p<0,05) en la serie de casos infectados: Preoperatorios Cirugía previa en la rodilla, terapia corticoidea, tratamiento con inmunosupresores, y artritis inflamatoria.

Intraoperatorios Tiempo quirúrgico excesivo, profilaxis antibiótica inadecuada, fractura periprotésica intraoperatoria. Postoperatorios Secreción persistente tras 10 días, hematoma palpable profundo, necesidad de nueva cirugía, trombosis venosa profunda en extremidades inferiores. Infecciones a distancia Cutánea, sepsis generalizada, urinaria, neumonía, abdominal.

Discusión y conclusionesEsta es la primera descripción de una fractura intraoperatoria y de una trombosis venosa profunda como hechos significativamente más frecuentes en las prótesis de rodilla con infección tardía. Asimismo se confirma la significación de otros factores de riesgo previamente descritos.

Infections in total knee arthroplasties (TKA) are usually classified into early (up to 3 months after the intervention), late and hematogenous.1 Early infections are the most common acute complications despite current prophylactic measures.2 The incidence of late infection reported in the literature ranges from 0.9–1%3,4 to 2.19%.5 Occasionally, patients and clinical situations with a high risk of infection are not correctly identified, thus increasing the probability of suffering these severe complications.

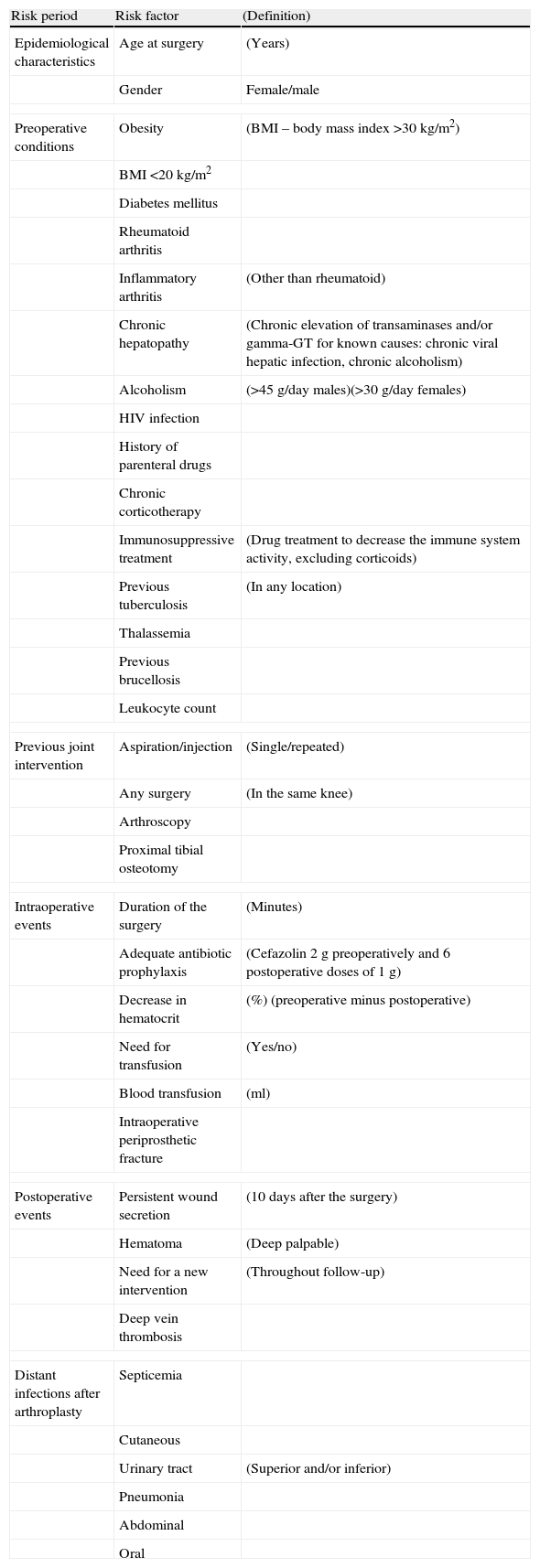

Multiple risk factors for infection of knee prostheses have been reported (Table 1),3–30 but most publications present one of the following problems: firstly, numerous studies focus exclusively on a specific problem,5–16 ignoring all the risk factors of each individual patient from a holistic perspective, secondly, the primary objective of some published series is not to analyze infection per se, instead the information on cases of infection is offered collaterally,7,8,10 and thirdly, the level of evidence of some articles is low because they deal with case series, non systematic reviews and expert opinions.10,13,16,17

Risk factors analyzed in cases with infection and in non-infected controls.

| Risk period | Risk factor | (Definition) |

| Epidemiological characteristics | Age at surgery | (Years) |

| Gender | Female/male | |

| Preoperative conditions | Obesity | (BMI – body mass index >30kg/m2) |

| BMI <20kg/m2 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Inflammatory arthritis | (Other than rheumatoid) | |

| Chronic hepatopathy | (Chronic elevation of transaminases and/or gamma-GT for known causes: chronic viral hepatic infection, chronic alcoholism) | |

| Alcoholism | (>45g/day males)(>30g/day females) | |

| HIV infection | ||

| History of parenteral drugs | ||

| Chronic corticotherapy | ||

| Immunosuppressive treatment | (Drug treatment to decrease the immune system activity, excluding corticoids) | |

| Previous tuberculosis | (In any location) | |

| Thalassemia | ||

| Previous brucellosis | ||

| Leukocyte count | ||

| Previous joint intervention | Aspiration/injection | (Single/repeated) |

| Any surgery | (In the same knee) | |

| Arthroscopy | ||

| Proximal tibial osteotomy | ||

| Intraoperative events | Duration of the surgery | (Minutes) |

| Adequate antibiotic prophylaxis | (Cefazolin 2g preoperatively and 6 postoperative doses of 1g) | |

| Decrease in hematocrit | (%) (preoperative minus postoperative) | |

| Need for transfusion | (Yes/no) | |

| Blood transfusion | (ml) | |

| Intraoperative periprosthetic fracture | ||

| Postoperative events | Persistent wound secretion | (10 days after the surgery) |

| Hematoma | (Deep palpable) | |

| Need for a new intervention | (Throughout follow-up) | |

| Deep vein thrombosis | ||

| Distant infections after arthroplasty | Septicemia | |

| Cutaneous | ||

| Urinary tract | (Superior and/or inferior) | |

| Pneumonia | ||

| Abdominal | ||

| Oral | ||

The aim of this study was to analyze, through a comparative study of cases and controls, all the risk factors described in the literature as statistically significant for infection of knee prostheses.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis was a comparative, retrospective and observational study of cases and controls. We compared the incidence of possible risk factors for infection among non-infected controls and patients with late infection in their knee prostheses.

Case seriesThe case series included 32 patients who had been diagnosed consecutively with late infection in their knee prostheses.

Inclusion criteria:

- (1)

Patients who underwent surgical intervention at the orthopedic surgery service of a teaching general hospital between January 1999 and December 2009.

- (2)

Suspicion of late infection: chronic severe pain, persistent signs of local inflammation (erythema and/or swelling), wound suppuration and/or fistula. Periostitis (periosteal reaction), endosteal erosions and focal osteolysis were considered as radiographic signs for suspicion of infection. Likewise, it was considered that infection was likely in cases of loosening or early migration of the implant, rapidly progressive radiotransparent lines and osteolysis with a rapid progression in the absence of obvious mechanical causes (incorrect implantation of the prosthesis and/or excessive polyethylene wear).

- (3)

Microbiological confirmation: at least 3 positive cultures of the same microorganisms originating from intraoperative samples and/or joint aspiration.

Control series:

Sample size (according to a prior statistical calculation): in order to calculate the sample size we decided to set the sample effect at a value of 0.3 (this value offered an intermediate level of statistical power in the χ2 test), the statistical power at a value of 0.8 and the level of significance (“P”) at 0.05. We then calculated the necessary sample size to fulfill these conditions, and obtained a minimum of 87 cases for the control group (this size was sufficient to determine differences). Lastly, we decided to analyze 100 controls selected randomly using a randomizing tool (random number generation tool from the software program Microsoft Office Excel 2007 installed on a computer with the operating system Microsoft Windows 7).

Inclusion criteria:

- (1)

Patients who underwent surgical intervention at the same service during the same period of time (from January 1999 until December 2009) and by the same surgeons.

- (2)

Patients with a complete follow-up according to current protocols (clinical and radiographic controls after 1, 3, 6 and 12 months of the surgery, and annually thereafter).

- (3)

Knee prostheses without symptoms, clinical or radiographic signs leading to suspicion of infection throughout the entire follow-up period (see “case series” section).

TKA with both cemented components (Triathlon, Stryker Iberia SL, Madrid, Spain; Rotational hinge, Waldemar Link GmbH&Co, Hamburg, Germany), with cemented tibial and patellar components (Optetrak, Exactech Inc, Gainesville, Florida, USA) or with all components uncemented and coated with hydroxyapatite (Excel-HAP, Surgical-Traiber, Valencia, Spain).

Follow-upMinimum of 18 months, mean 84 months, range 18–144 months. No patients were lost during the entire follow-up period.

Risk factorsWe investigated all the risk factors described in the literature,3–30 classifying them according to the risk period (Table 1). This retrospective analysis took into account the following items in the record of each patient: history and notes by the family physician; preoperative hospital history; preanesthetic assessment; surgical, anesthetic and surgery room nursing reports, as well as reanimation; medical and nursing postoperative histories; postoperative hospital history, including follow-up at outpatient orthopedic and traumatology consultation; all the remaining records available in primary and hospital care.

Other definitionsThe antibiotic prophylaxis protocol followed at our hospital from 1999 until 2009 consisted of 2g of intravenous cefazolin preoperatively, followed by 6 doses of 1g every 8h (in other words, prophylaxis was prolonged for 48h); in case of allergy to beta-lactams we administered 1g of vancomycin preoperatively, followed by 4 doses of 1g every 12h. For statistical purposes, any deviation from this protocol was considered as inadequate prophylaxis. We defined as excessively prolonged surgical time those cases in which it extended over 110min (75% of the time according to the definitions of the NNIS).12 Deep palpable hematoma was a collection of blood located at least under the cutaneous layer of the skin, liquid (with palpable fluctuation), and painful. We investigated all distant septic foci in all medical and nursing patient histories.

Statistical analysisWe created contingency tables with absolute numbers for every variable. The Pearson chi-squared test was applied for the statistical analysis of qualitative variables. For the comparison of quantitative variables we used an analysis of variance, which employed the Snedecor “F” as contrast statistic.

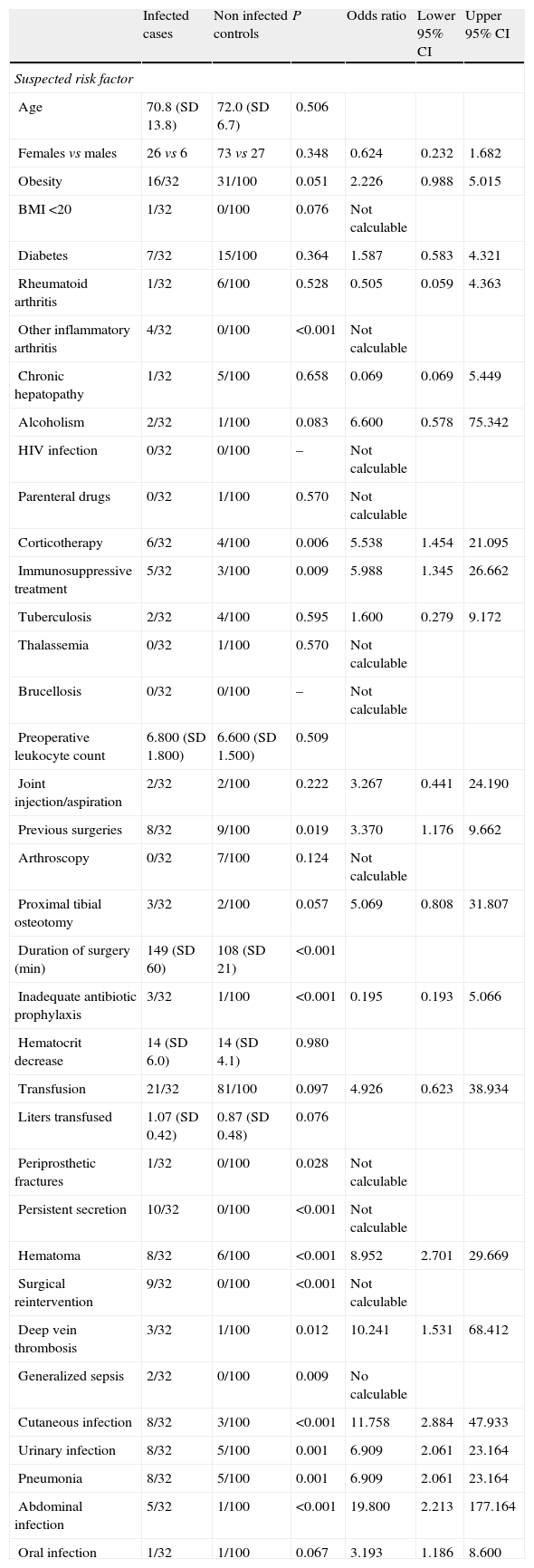

The differences between infected cases and non-infected controls were considered statistically significant when the value of P was less than 0.05. In cases with statistical significance of the previously mentioned analyses we carried out simple post hoc comparisons adjusting the level of significance through the Bonferroni method to control the rate of error. The description of the results was carried out based on these comparisons.31 All the statistical calculations were carried out using the software package SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) (Table 2).

Incidence of risk factors among 32 infected cases and in 100 non-infected controls with knee arthroplasties.a

| Infected cases | Non infected controls | P | Odds ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

| Suspected risk factor | ||||||

| Age | 70.8 (SD 13.8) | 72.0 (SD 6.7) | 0.506 | |||

| Females vs males | 26 vs 6 | 73 vs 27 | 0.348 | 0.624 | 0.232 | 1.682 |

| Obesity | 16/32 | 31/100 | 0.051 | 2.226 | 0.988 | 5.015 |

| BMI <20 | 1/32 | 0/100 | 0.076 | Not calculable | ||

| Diabetes | 7/32 | 15/100 | 0.364 | 1.587 | 0.583 | 4.321 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1/32 | 6/100 | 0.528 | 0.505 | 0.059 | 4.363 |

| Other inflammatory arthritis | 4/32 | 0/100 | <0.001 | Not calculable | ||

| Chronic hepatopathy | 1/32 | 5/100 | 0.658 | 0.069 | 0.069 | 5.449 |

| Alcoholism | 2/32 | 1/100 | 0.083 | 6.600 | 0.578 | 75.342 |

| HIV infection | 0/32 | 0/100 | – | Not calculable | ||

| Parenteral drugs | 0/32 | 1/100 | 0.570 | Not calculable | ||

| Corticotherapy | 6/32 | 4/100 | 0.006 | 5.538 | 1.454 | 21.095 |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 5/32 | 3/100 | 0.009 | 5.988 | 1.345 | 26.662 |

| Tuberculosis | 2/32 | 4/100 | 0.595 | 1.600 | 0.279 | 9.172 |

| Thalassemia | 0/32 | 1/100 | 0.570 | Not calculable | ||

| Brucellosis | 0/32 | 0/100 | – | Not calculable | ||

| Preoperative leukocyte count | 6.800 (SD 1.800) | 6.600 (SD 1.500) | 0.509 | |||

| Joint injection/aspiration | 2/32 | 2/100 | 0.222 | 3.267 | 0.441 | 24.190 |

| Previous surgeries | 8/32 | 9/100 | 0.019 | 3.370 | 1.176 | 9.662 |

| Arthroscopy | 0/32 | 7/100 | 0.124 | Not calculable | ||

| Proximal tibial osteotomy | 3/32 | 2/100 | 0.057 | 5.069 | 0.808 | 31.807 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 149 (SD 60) | 108 (SD 21) | <0.001 | |||

| Inadequate antibiotic prophylaxis | 3/32 | 1/100 | <0.001 | 0.195 | 0.193 | 5.066 |

| Hematocrit decrease | 14 (SD 6.0) | 14 (SD 4.1) | 0.980 | |||

| Transfusion | 21/32 | 81/100 | 0.097 | 4.926 | 0.623 | 38.934 |

| Liters transfused | 1.07 (SD 0.42) | 0.87 (SD 0.48) | 0.076 | |||

| Periprosthetic fractures | 1/32 | 0/100 | 0.028 | Not calculable | ||

| Persistent secretion | 10/32 | 0/100 | <0.001 | Not calculable | ||

| Hematoma | 8/32 | 6/100 | <0.001 | 8.952 | 2.701 | 29.669 |

| Surgical reintervention | 9/32 | 0/100 | <0.001 | Not calculable | ||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 3/32 | 1/100 | 0.012 | 10.241 | 1.531 | 68.412 |

| Generalized sepsis | 2/32 | 0/100 | 0.009 | No calculable | ||

| Cutaneous infection | 8/32 | 3/100 | <0.001 | 11.758 | 2.884 | 47.933 |

| Urinary infection | 8/32 | 5/100 | 0.001 | 6.909 | 2.061 | 23.164 |

| Pneumonia | 8/32 | 5/100 | 0.001 | 6.909 | 2.061 | 23.164 |

| Abdominal infection | 5/32 | 1/100 | <0.001 | 19.800 | 2.213 | 177.164 |

| Oral infection | 1/32 | 1/100 | 0.067 | 3.193 | 1.186 | 8.600 |

Quantitative variables: arithmetic mean±SD (standard deviation).

95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

We did not detect any epidemiological datum which was more prevalent among infected patients, neither gender nor age.

Among the preoperative characteristics of patients, previous surgery in the same knee, inflammatory arthritis other than rheumatoid, and treatments with corticoids and immunosuppressive agents were significantly more frequent in the infected knee prostheses. On the other hand, we did not find any statistically significant differences in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, obesity, body mass index (BMI)<20, rheumatoid arthritis, cirrhosis and chronic hepatopathies, alcoholism, parenteral drug addiction, tuberculous infection (in any location), thalassemia, intraarticular injections in the same knee, tibial osteotomy, arthroscopy in the same knee, and/or preoperative leukocyte count.

Intraoperative events which were statistically related to infection of the prosthesis were an excessively prolonged surgical time, inadequate antibiotic prophylaxis (specifically when erythromycin was used instead of cefazolin or vancomycin), and intraoperative periprosthetic fracture (although in this case statistical significance was based on a single event in the series of infected cases). We did not detect any differences in the decrease of hematocrit or in the need for postoperative blood transfusion.

Among the postoperative events, wound secretion beyond 10 days, deep palpable hematoma, the need for another intervention and deep vein thrombosis were significantly more frequent in infected knees.

Among the distant infections suffered by patients after implantation of a knee prosthesis, those statistically related to prosthetic infection were septicemias (generalized sepsis), cutaneous, urinary (both in the superior and inferior urinary tract), pneumonias, and several abdominal infections. It is also worth noting that the bacteria cultured in the infected knee prostheses were not compared with those present in the distant infection (in some cases, like pneumonias, there were no cultures available). On the other hand, no statistically significant differences were found in the prevalence of severe oral and/or dental infections.

DiscussionWe did not find epidemiological characteristics (gender or age) which were more frequent in infected knee prostheses than in non-infected controls, although some reports describe a higher risk among males.3

There are various reports on the preoperative conditions of patients. In the first group of these conditions, the results of our case-control comparison showed agreement with those published in some works regarding the importance of risk factors related to previous surgery in the same knee, chronic treatment with glucocorticoids, inflammatory arthritis other than rheumatoid, and immunosuppressive treatments,3,18,19 although there is certain controversy regarding immunosuppression in psoriatic arthritis.19 Regarding the second group of factors, neither the literature reviewed nor the present work were able to prove any statistical significance: alcoholism, intravenous drug addiction, previous tuberculous infection, and thalassemia.3,4,18 The importance of a third group of preoperative conditions is very controversial as no statistical significance was found in our series and the literature is not conclusive: diabetes mellitus,7,8,18,20,29,30 obesity and BMI<20,4,9,18,20,21,30 rheumatoid arthritis,3,4,6,20 and previous intraarticular aspiration/injection in the same knee.11 In the case of diabetes, it appears that, recently, some authors are starting to pay more attention to metabolic control of the disease than to the diagnosis itself, mainly considering the levels of glycosylated hemoglobin.29,32

The authors are not aware of any reports of intraoperative fractures as a risk factor for infection of knee prostheses, and in our comparison it was significantly more frequent among infected patients, although it is worth pointing out that statistical significance was only reached with 1 single infected case vs no infected controls (Table 2). Other significant intraoperative data in this series, such as excessively prolonged surgical time and inadequate antibiotic prophylaxis, are clearly reflected in the majority of publications in this regard.13,18,23 On the other hand, we did not find differences between cases and controls in the decrease of hematocrit or in the need for transfusion, aspects in which the literature offers conflicting results.22

In addition, this is the first description known by the authors of the statistical association between deep vein thrombosis and late infection in knee prostheses. Other significant postoperative events include wound secretion after 10 days, palpable deep hematoma, and the need for new interventions in the same knee. The majority of articles recognize the importance of these 3 events,3,8,14,15,18,24 but some publications differ.12

Among the distant infections experienced by patients with knee prostheses, those which bore statistical association with infection of the arthroplasty were generalized sepsis, cutaneous, urinary tract infections, pneumonias, and some abdominal infections. This statistical association coincides with the reports in some articles.18,20,25 On the other hand, we have not found any significant differences between cases and controls regarding the prevalence of severe oral infections, although this lack of significance could be due to the fact that we only recorded 1 case. The literature in this respect is not clear and the topic is the subject of ongoing debate.26–28

The main limitation of this work is the scarce number of infected cases. Fortunately, infection of a knee prosthesis is an infrequent complication, with less than 2.5% in most series.3–5 In order to minimize the consequences of this low incidence, we calculated the statistical power a priori (see “Methods” section) to determine the sample sizes. The second limitation is derived from the fact that the theoretical number of risk factors is practically infinite, so from a practical standpoint, it is impossible to register all of them. However, we analyzed all the risk factors described in the literature for any type of implant (not only knee arthroplasties),3–30 and we also added some which were very prevalent in our series of infected cases (like deep vein thrombosis). Through the application of both strategies (analysis of statistical power and analysis of all the risk factors described) we were able to demonstrate the statistical significance of certain risk factors, some of them previously unreported. The third limitation stems from the fact that, for some risk factors, the number of infected cases was very low, so the statistical significance obtained was also very low. This was the case with parenteral drug addiction and tuberculosis.

The authors are not aware of previous descriptions of intraoperative fracture and postoperative deep vein thrombosis as significantly more frequent events in late infections of knee prostheses. Furthermore, this comparison of cases and controls studied all the risk factors described in the literature in all patients, assessing which of them were significantly more frequent among infected cases, so its results could offer an overall, holistic view, unlike many other published works, which focus on a single specific problem. It is important to know and identify these risk factors in each patient for 2 reasons: firstly, it is essential to optimize the preoperative condition, controlling and minimizing risk factors or, when this is not possible, assessing the possibility of establishing special prophylactic measures, like additional and/or prolonged antibiotics, for example; secondly, if the arthroplasty causes postoperative problems, determining the probability of infection and whether the patient is at low or high risk will help to gauge the level of screening for those infections.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data. The procedures used on patients and control subjects respected the confidentiality of personal information. All patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written and verbal informed consent to participate in the study.

This investigation adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki adopted by the World Medical Association. This observational retrospective study was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors wish to thank María José de Dios, Professor of Biostatistics, for her support with the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: de Dios M, Cordero-Ampuero J. Factores de riesgo para la infección en prótesis de rodilla, incluyendo la fractura intraoperatoria y la trombosis venosa profunda, no descritos previamente. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:36–43.