The peroneal tendon pathology is a common cause of posterolateral ankle pain. Recently, the incidence and awareness of this disease and its treatment are booming thanks to the development of tendoscopic procedures.

ObjectiveTo describe and assess the current role and indications of tendoscopy for peroneal tendon pathology.

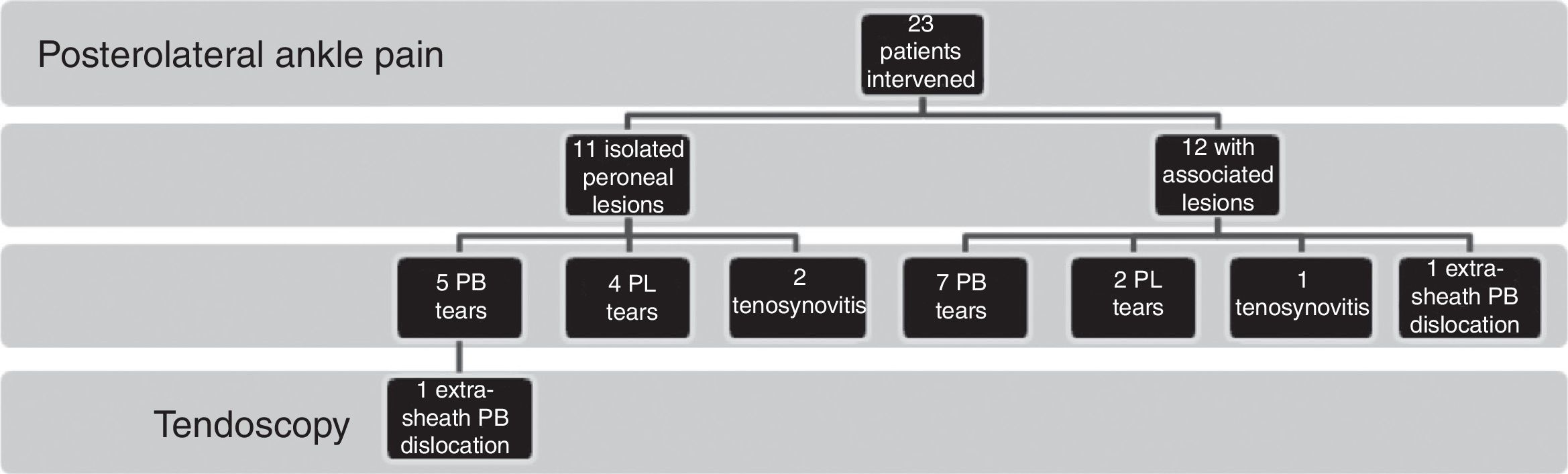

Material and methodsFrom June 2010 to July 2011, twenty three patients with retrofibular pain were treated with peroneal tendoscopy. We founded twelve peroneal brevis tendon tears, six peroneal longus tendon tears, three cases of tenosynovitis and two cases of luxation, one patient with an intrasheath subluxation and another one of extrasheath. Of the 23 patients, 12 had another injury associated: 4 talar osteochondral lesions, 3 instabilities and 7 cases of soft tissue impingement.

DiscussionThe three main indications include tendon tears, tenosynovitis and subluxation or luxation. It is a technically demanding procedure that requires extensive experience in arthroscopic management of small joints and can be particularly complex in cases of wide tenosynovitis, broad tendon tears or anatomical defects but very useful for the evaluation of the lesions and for the treatment of peroneal tendon disorders.

ConclusionsTendoscopy is a useful procedure with low morbidity and excellent functional results to treat the pathology of the peroneal tendons.

La patología de los tendones peroneos es una causa frecuente de dolor posterolateral de tobillo. En los últimos años, la incidencia y el conocimiento de esta patología y de su tratamiento están en auge gracias al desarrollo de las técnicas tendoscópicas.

ObjetivoDescribir y evaluar el estado actual y las indicaciones de la tendoscopia en la patología de los tendones peroneos.

Material y métodoDesde junio de 2010 hasta julio de 2011 se realizaron 23 tendoscopias en pacientes con dolor retrofibular persistente. Encontramos 12 casos de rotura del peroneus brevis, 6 del peroneus longus, 3 casos de tenosinovitis y 2 casos de luxación, uno de ellos con una luxación intravaina y otra extravaina. De los 23 pacientes, 12 presentaban además otra lesión asociada: 4 lesiones osteocondrales de astrágalo, 3 inestabilidades anterolaterales de tobillo y 7 casos de pinzamiento de partes blandas.

DiscusiónLas 3 indicaciones principales de esta técnica son las tenosinovitis, las roturas tendinosas y la luxación de los tendones. Es un procedimiento técnicamente exigente, que requiere una amplia experiencia en el tratamiento artroscópico de pequeñas articulaciones y puede ser especialmente complejo en los casos de tenosinovitis extensa o amplias roturas tendinosas, pero muy útil para la evaluación y tratamiento de dicha patología.

ConclusionesLa tendoscopia es un procedimiento de gran utilidad en el abordaje de la patología de los tendones peroneos, con baja morbilidad y excelentes resultados funcionales.

The peroneal tendoscopy technique was described by Van Dijk and Kort1 in 1998. Van Dijk2,3 conducted a study of the anatomy of the tendons. Since then, this technique has been gaining importance and popularity for the treatment of peroneal tendon pathologies. It not only enables the anatomical evaluation of tendons, but also a dynamic assessment of their position and mobility within the sheaths through which they move. Using a minimally invasive approach, it is possible to diagnose and treat tenosynovitis, tendon ruptures, dislocations, anatomical variants such as accessory muscles, peroneus brevis (PB) with a low insertion belly, the presence of peroneus tercius or quartus, bony prominences and ruptures of the sheath.

In addition to being a minimally invasive technique, tendoscopy has the advantage of accessibility, partly due to the anatomical arrangement of tendons, as well as a minimal risk of neurovascular and soft tissue lesion compared to open techniques.

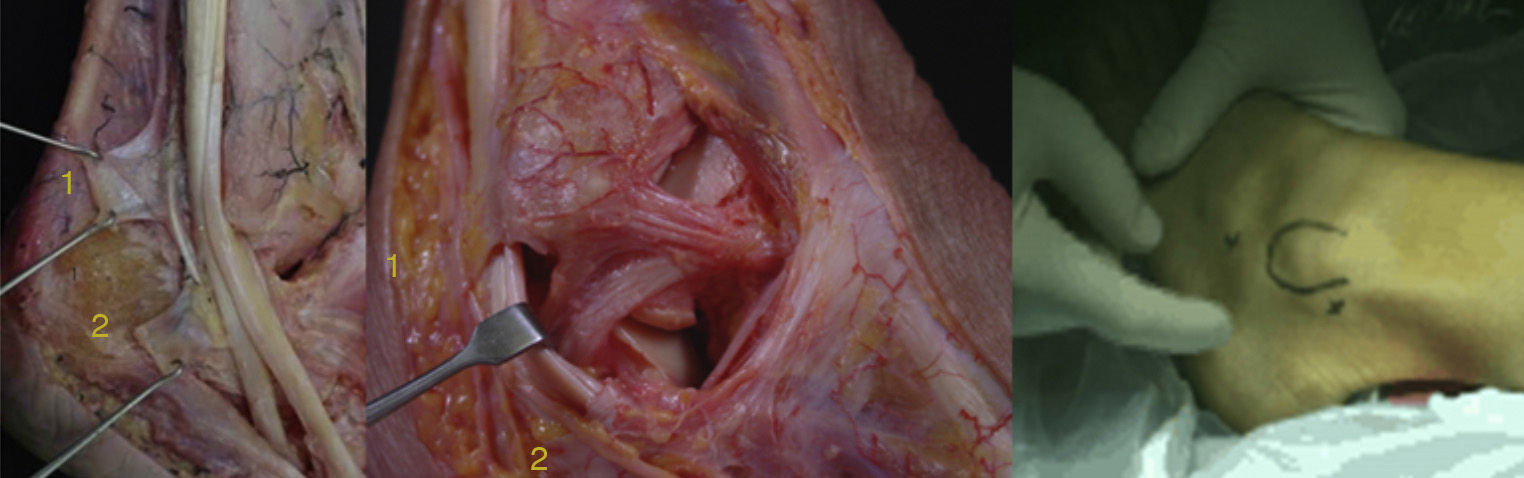

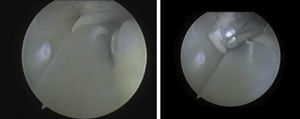

AnatomyThe peroneal muscles are located in the lateral compartment of the leg. The PB originates in the distal two thirds of the fibula and the interosseous membrane. The peroneus longus (PL) originates in the proximal two thirds of the lateral external malleolus. Both become tendons before reaching the ankle joint; the longus approximately 4cm from the tip of the fibula with a long musculotendinous joint, while the muscle fibers of the brevis are slightly more distal, often passing beyond the malleolus. Both are innervated by the superficial peroneal nerve. At the level of the lateral malleolus, the PB is located within a fibro-osseous tunnel, adjacent and posterior to the fibula, and is stabilized within by the PL muscle tendon and superior peroneal retinaculum (SPR) (Fig. 1).

The tendons run through a common synovial sheath from about 4cm proximal to the lateral malleolus. The synovial sheath passes through the fibrous bone tunnel which is posterolaterally stabilized by the SPR and medially stabilized by the posterior talofibular ligament, the calcaneofibular ligament and the posteroinferior tibiofibular ligament. Anteriorly, it is stabilized by the distal fibula. The SPR is essential to maintain the stability of peroneal tendons. This structure originates in the lateral region of the distal fibula. Its insertion is variable; at least 5 different types have been identified.4

The most common type (47%) has 2 bands; a superior band which inserts anteriorly to the sheath of the Achilles and an inferior band which inserts into the lateral wall of the calcaneus, at the level of the peroneal tubercle (or trochlear process).

Both tendons possess independent vascularisation through the vinculum. This latter structure connects each tendon to its sheath and, in addition to providing vascularisation through the posterior peroneal artery, has a controversial role in proprioception, which could be related to chronic ankle pain. The vinculum penetrates into the posterolateral region of each tendon within the retromalleolar groove (or sulcus) and throughout its entire path.5

In 2009, Sammarco described 4 anatomical regions according to the arrangement of the tendons in their path.6 A proximal region, from the SPR to the tip of the fibula, in which the PB tendon is arranged anteriorly to the PL; a second region from the inferior peroneal retinaculum (IPR) to the lateral peroneal tubercle of the calcaneus, where the PL is inferior to the PB; and 2 regions distal to the inferior portion of the IPR, in which the tendon sheath divides into separate sheaths at the level of the peroneal tubercle of the calcaneus towards their insertions into the base of the first and fifth metatarsals.

The os perineum is an accessory bone located in the PL tendon. It is ossified in approximately 20% of feet. It is located in a plantar direction relative to the cuboid and the calcaneocuboid joint. The peroneus quartus is an accessory muscle which may be present in 13–22% of the population and can be found in the lateral compartment.7 The peroneus quartus often originates in the PB and is inserted into the peroneal tubercle of the calcaneus. Knowledge of these anatomical variants is important to rule impingement syndromes of the peroneals, due to a space conflict in the retromalleolar canal (Fig. 2).

Surgical techniquePatients were placed in a lateral position under regional spinal anesthesia and ischemia. The distal and proximal portals were created along the path of the peroneal tendons 1–1.5cm distally and 3cm proximally to the tip of the lateral malleolus, respectively. Accessory portals were sometimes created, depending on the location and extent of the disease.

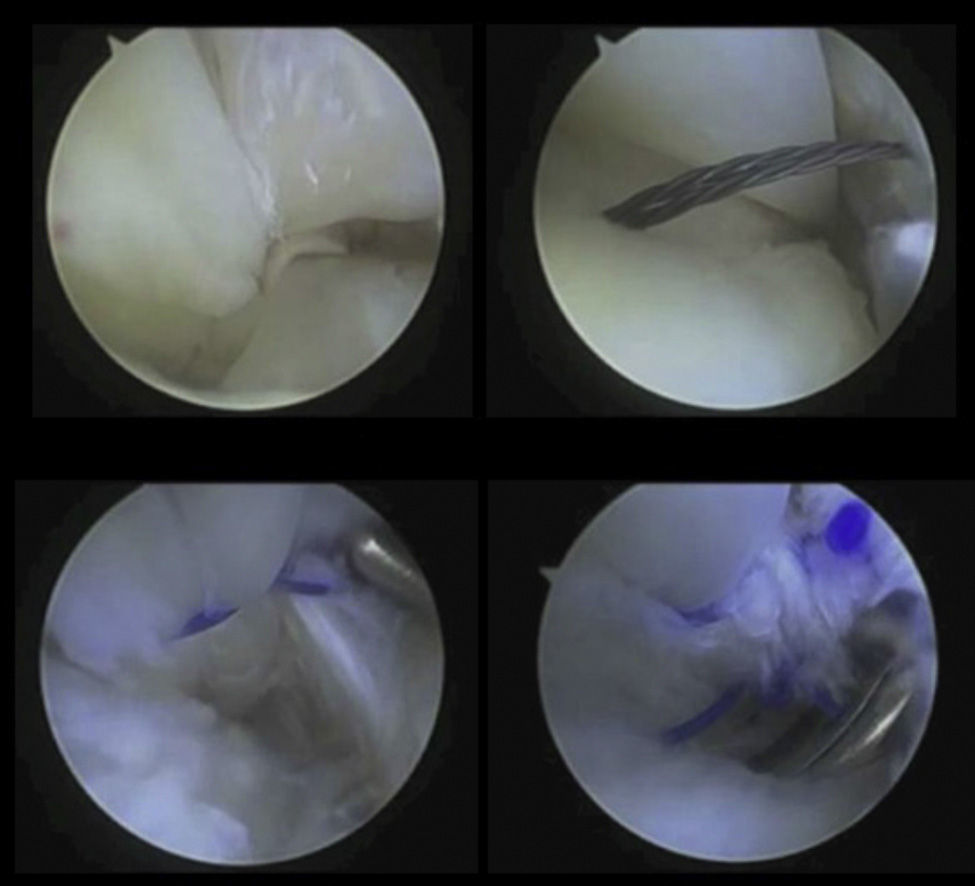

We first created the distal portal by making an incision on the skin and tendon sheath, using the standard, 4.0mm, 30° arthroscope. So as to avoid tearing the sheath and damaging the tendons, this procedure was performed with the ankle in plantar flexion. Once the distal portal was created, and under direct visualization, we established the proximal portal. The presence of synovitis was a common finding, in which case we conducted an endoscopic synovectomy prior to tendon exploration. Longitudinal tears of the tendons could be debrided and repaired by tendoscopy with a curved needle (Arthrex® Mini Suture Lasso).

Material and methodBetween June 2010 and July 2011, a total of 23 patients presenting retromalleolar ankle pain were operated by tendoscopy of the peroneal tendons at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery of 12 de Octubre University Hospital and Quirón-USP San Camilo Hospital, in Madrid (Fig. 3). Of these, 20 were male. The mean age at the time of surgery was 32 years (range: 21–43 years) and the mean follow-up period was 6 months (range: 6–21 months). A total of 20 patients had a history of previous sprain with a forced inversion mechanism in the affected ankle prior to the onset of symptoms.

ResultsIn total, 11 patients suffered an isolated pathology of the peroneal tendons, whilst 12 presented associated injuries: 4 astragalus (or talus) osteochondral lesions (2 grade II and 2 grade III), 3 cases of anterolateral ankle instability and 7 cases of anterolateral soft tissue impingement. One patient presented a grade III osteochondral lesion associated with anterolateral instability and another presented instability associated to anterolateral ankle impingement.

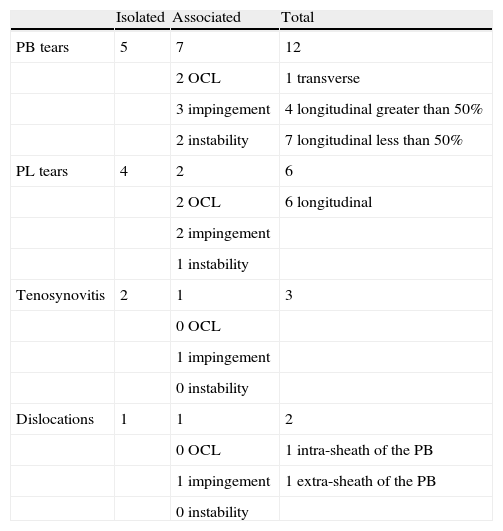

We identified 12 PB tendon ruptures, 6 PL longitudinal ruptures, 3 cases of tenosynovitis and 2 patients with dislocations, 1 intra-sheath type B and 1 extra-sheath. PB lesions were mostly longitudinal tears, 4 of which were greater than 50% of the cross section and requiring surgical repair (1 mini-open and 3 tendoscopic sutures) and 7 cases with tears less than 50%. In 1 patient who underwent PB repair due to a longitudinal tear we associated a deepening of the retromalleolar groove due to intra-sheath dislocation. Another case suffered a transverse PB tear which required a mini-open repair technique. PL tears were longitudinal in all cases, requiring debridement and tubulisation (Table 1). Two operated patients required a lateral displacement osteotomy of the calcaneus (inverted Koutsogiannis) and all patients with ankle instability were treated with an associated surgical action: through reinsertion of the anterior talofibular ligament in 1 case and with an arthroscopic homograft plasty in 2 cases.

Type of lesion and associations.

| Isolated | Associated | Total | |

| PB tears | 5 | 7 | 12 |

| 2 OCL | 1 transverse | ||

| 3 impingement | 4 longitudinal greater than 50% | ||

| 2 instability | 7 longitudinal less than 50% | ||

| PL tears | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| 2 OCL | 6 longitudinal | ||

| 2 impingement | |||

| 1 instability | |||

| Tenosynovitis | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 0 OCL | |||

| 1 impingement | |||

| 0 instability | |||

| Dislocations | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 0 OCL | 1 intra-sheath of the PB | ||

| 1 impingement | 1 extra-sheath of the PB | ||

| 0 instability |

OCL: osteochondral lesion; PB: peroneus brevis; PL: peroneus longus.

Regarding complications, we observed 1 case neuropraxia of the sural nerve which has recovered partially.

DiscussionPeroneal tendon pathology is often overlooked or misdiagnosed as a sprained lateral external ankle ligament, with patients following multiple conservative treatments which fail to correct the symptoms. It is important to take into account that isolated sprains of the posterior talofibular ligament are exceptional, so we must always suspect the existence of this pathology when patients present pain at that level. When deciding the most appropriate surgical technique it is essential to support the decision with a correct history which includes a clinical examination to evaluate the mechanism of injury, the tendon path in dorsal flexion and inversion-eversion and the anterolateral stability of the ankle,18,19 as well as hindfoot varus desaxation along with a detailed study of the malleolar groove and the remaining possible anatomical variants and predisposing factors.

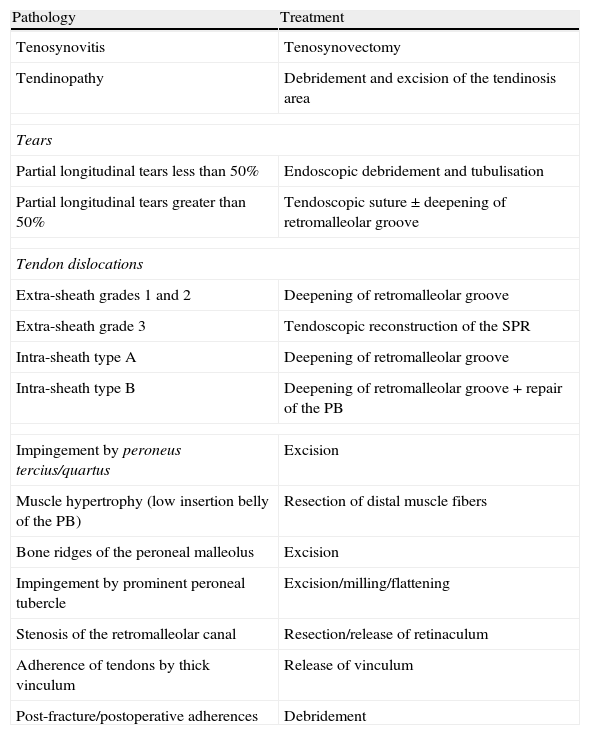

Tendoscopy20 allows us to carry out a more detailed assessment of both tendon injuries and other associated lesions, as well as enabling a dynamic assessment thereof in the interior of the sheath and throughout the entire path. Our indications were all those included in Table 2. This is a minimally invasive technique with less surgical morbidity than open procedures, which allows a shorter hospital stay and a quicker recovery and return to sport activities.

Surgical treatment and indications.

| Pathology | Treatment |

| Tenosynovitis | Tenosynovectomy |

| Tendinopathy | Debridement and excision of the tendinosis area |

| Tears | |

| Partial longitudinal tears less than 50% | Endoscopic debridement and tubulisation |

| Partial longitudinal tears greater than 50% | Tendoscopic suture±deepening of retromalleolar groove |

| Tendon dislocations | |

| Extra-sheath grades 1 and 2 | Deepening of retromalleolar groove |

| Extra-sheath grade 3 | Tendoscopic reconstruction of the SPR |

| Intra-sheath type A | Deepening of retromalleolar groove |

| Intra-sheath type B | Deepening of retromalleolar groove + repair of the PB |

| Impingement by peroneus tercius/quartus | Excision |

| Muscle hypertrophy (low insertion belly of the PB) | Resection of distal muscle fibers |

| Bone ridges of the peroneal malleolus | Excision |

| Impingement by prominent peroneal tubercle | Excision/milling/flattening |

| Stenosis of the retromalleolar canal | Resection/release of retinaculum |

| Adherence of tendons by thick vinculum | Release of vinculum |

| Post-fracture/postoperative adherences | Debridement |

PB: peroneus brevis; SPR: superior peroneal retinaculum.

The technique can be performed under local anesthesia as a diagnostic procedure in selected patients. Its main disadvantage is that it is technically demanding, requires extensive experience in the arthroscopic management of feet, ankles and small joints and can be particularly complex in cases of extensive tenosynovitis, with large tendon ruptures or anatomical defects and in patients who have undergone prior surgical interventions.

Tearing of the tendon sheath should be avoided during the passage of the surgical instrumentation, causing a collapse of the sheath and fluid extravasation which impede the tendoscopy. It is also possible to damage the tendons themselves when entering the sheath, especially when adhesions are present. In order to avoid this, it is important to inject an adequate amount of serum into the sheath, thus creating more space around the tendon, and to insert the instruments with the ankle in plantar flexion. Lesions of the superficial peroneal nerve (or its medial and intermediate dorsal cutaneous branches) above zone A when creating the proximal or sural nerve portals, which may be very close to the distal portal in zone B, are infrequent.

Therefore, the possibility of a lesion of the peroneal tendons should be taken into account in all cases of lateral malleolar pain, with symptoms ranging from tenosynovitis to longitudinal or transverse (much less frequent) tendon ruptures, or dislocations thereof. A study of this pathology should be performed routinely in order to rule out the presence of varus desaxation and anterolateral ankle instability. Hindfoot varus desaxation must be corrected while treating the tendon lesion, especially in cases of tears which may progress to larger sizes and intra-sheath dislocations.

In our series, we found 3 patterns of tendoscopic findings: (1) tenosynovitis, (2) tendon ruptures, and (3) tendon instability. Surgical results were uniformly good in all 3 groups.

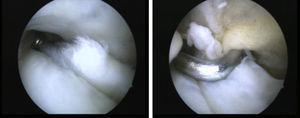

TenosynovitisUntil recently, the most common indication for a tendoscopy was tenosynovitis. This is caused by a prolonged and repeated activity, and mainly appears in athletes or chronically in patients who have suffered recurrent sprains or ankle deformities and instability. Furthermore, certain anatomical factors, such as the presence of peroneus tercius or quartus, peroneal muscle hypertrophy or a low insertion belly of the PB, can predispose towards a narrowing within the retromalleolar groove, thus favoring the onset of inflammatory processes (Fig. 4). The presence of tumefaction in the path of the tendons together with pain which increases upon passive plantar flexion and inversion, and with dorsiflexion and active resisted eversion is very characteristic. Magnetic resonance tests in T2 reveal the presence of fluid around the tendons. Occasionally, the injection of an anesthetic agent into the sheath may help in the differential diagnosis with other causes of posterolateral ankle pain.

Tendoscopy is indicated in cases which are refractory to conservative treatment after 6 months, including debridement and tenosynovectomy, as well as correction of any associated anatomical variants such as resection of accessory muscles or cases with low implantation bellies, which may cause retromalleolar impingement.

Tendon rupturesIsolated tears of the peroneal tendons are rare, most are the result of ankle inversion trauma. The prevalence of PB tendon injury found in cadaver studies ranged between 11% and 37%, while that of PL tears was less frequent. Dombek et al.8 described PB lesions in 88% and PL lesions in 13% of 40 patients treated surgically for tendon ruptures. Among patients treated surgically for torn peroneal tendons, up to 33% also presented lateral ankle instability requiring ligament reconstruction, 20% dislocation, 10% an insufficient retromalleolar groove, 33% had a low insertion belly of the PB muscle and between 32% and 82% had a cavo-varus hindfoot.

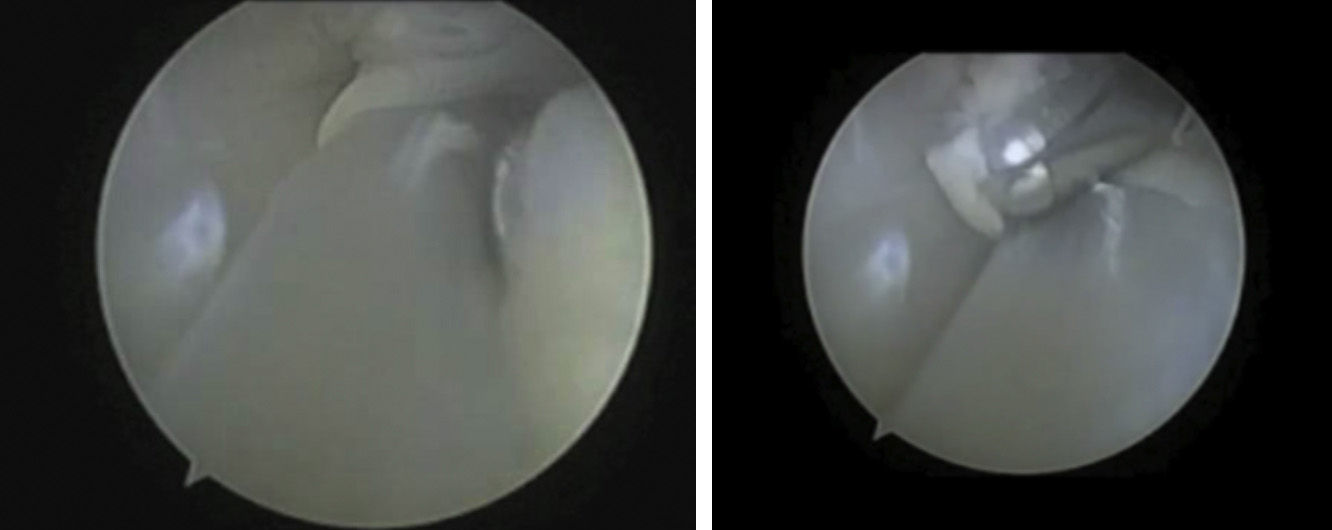

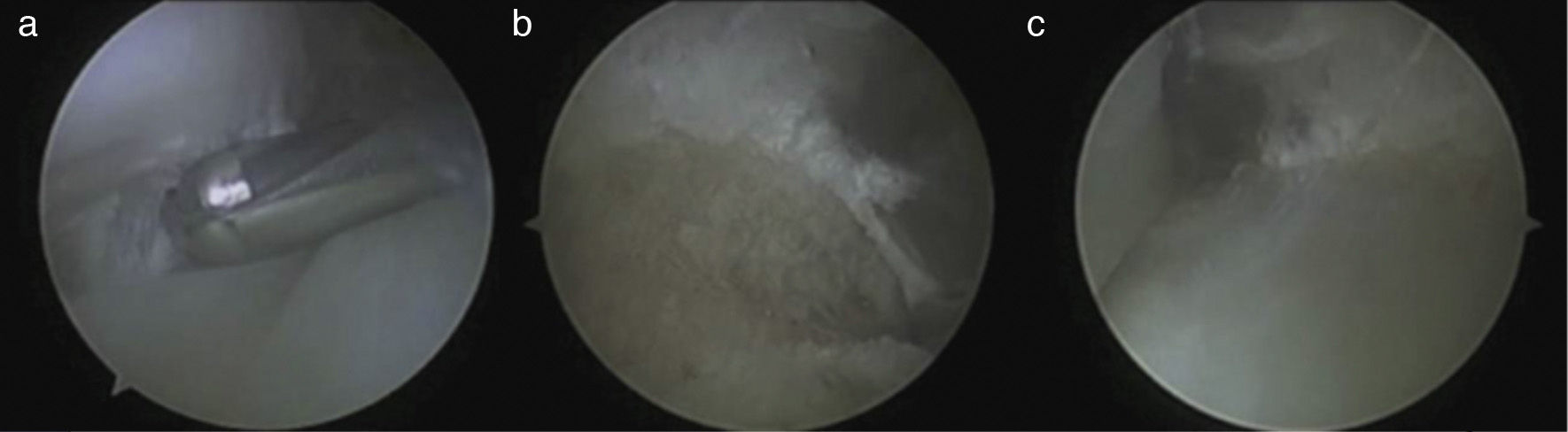

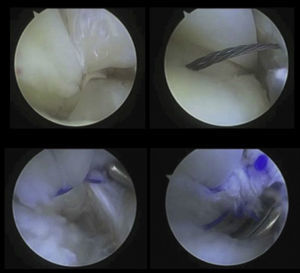

PB tears are usually found within the malleolar sulcus, which indicates that their origin is probably mechanical trauma in this region. It is less frequent for PB tendon ruptures to occur just proximal to their insertion into the fifth metatarsal by a sudden foot inversion mechanism. PL tears usually occur at the level of the cuboid, in the os perineum, in the peroneal tubercle or at the tip of the lateral malleolus. As proposed by Krause and Brodskym,9 for partial longitudinal tears (less than 50% of the cross section) we recommend tendoscopic debridement and tubulisation (Fig. 5), while in tears affecting over 50%, the treatment of choice is tendon suture, associated or not to a deepening of the retromalleolar groove (Fig. 6). When the repair requires more than 2 or 3 sutures, we believe that conducting selective open repair is most appropriate.

Peroneal tendon instabilityMonteggia10 was the first author to describe instability of the peroneal tendons in a ballet dancer in 1803. Its incidence is estimated at 0.3–0.5% of ankle injuries. In general, dislocation of the peroneal tendons is secondary to a history of trauma with the foot in dorsiflexion, abduction and inversion, resulting in a sudden contraction of the peroneal muscles. Patients present pain in the posterolateral region of the ankle and sometimes a feeling of instability on uneven surfaces and of a projection in the lateral malleolus. There are 2 main factors that can contribute to tendon dislocation: anterolateral ankle instability and varus malalignment of the hindfoot. Both factors should be examined and treated in case they coexist.

There are some anatomical variants that can predispose towards instability or subluxation, including the shape and depth of the retromalleolar groove and the presence or absence of a fibrocartilage groove. Edwards11 carried out a classic work on 178 feet from cadavers and described 82% of concave, 11% of flat and 7% of convex retromalleolar grooves. When present, the groove had a mean width of 6mm (range: 5–10mm) and a limited depth which occasionally reached 3mm. An inadequate retromalleolar groove, SPR laxity due to a valgus calcaneus foot and neuromuscular diseases and congenital absence of the SPR, are all factors which may contribute to the mechanism of dislocation.

In 1976, Eckert and Davis12 carried out a classification of peroneal tendon dislocations according to SPR disinsertion from the periosteum and/or fiber channel. Subsequently, in 1987, Oden13 amended it by adding a fourth grade. Grade 1 or subluxation (51%) occurs when the SPR becomes disinserted from the peroneal malleolus, allowing the tendons to move in an anterior direction. In grade 2 (33%), the fibrous annulus is detached along with the SPR. Grade 3 (13%) occurs when a small bone fragment of the peroneal malleolus is avulsed together with the SPR and the annulus (radiologically described as the “fleck sign”). Lastly, grade 4, the least frequent, is defined as a complete avulsion or tear of the posterior insertion of the SPR, with the tendons running superficially and laterally.

Recently, Raikin et al.14 described a new type of dislocation of the peroneal tendons in which the SPR was intact, and defined it as an intra-sheath dislocation. They classified it into 2 subgroups: type A, in which there is no tendon rupture and the tendons change their relative position momentarily (PL runs deeper than PB), and type B, in which the PL tendon is dislocated by a longitudinal tear of the PB tendon, losing its position in the retromalleolar groove.

The redislocation rate with conservative treatment is very high. It may be an option exclusively in cases of acute dislocation. The success rate in these cases is 40–57% and it is not indicated for high-level athletes.

Surgical treatment provides excellent results, especially in cases of acute dislocation, and is the only option in cases of recurrent dislocation. It is indicated in young patients who practice high-level sports and require a rapid return to activity. Surgery prevents situations such as tenosynovitis and longitudinal tears, which are often associated with peroneal tendon instability.

In cases of extra-sheath dislocation of grades 1 and 2 and in type A intra-sheath dislocation, we recommend techniques which deepen the retromalleolar sulcus,15 with the tendoscopic technique being of choice when used as an isolated procedure. The association of SPR reconstruction techniques in types 1 and 2 is controversial. In type 3, the treatment of choice is retinacular reconstruction, often using bone anchors seeking consolidation of the avulsed fragment. In type 4, reconstruction or deepening techniques are often insufficient, thus requiring reinforcement. Finally, the treatment of choice in type B intra-sheath dislocations is a repair of the PB longitudinal tear associated to groove deepening.

In 2006, Lui16 described the endoscopic reconstruction of the peroneal retinaculum. Eckert and Davis12 published excellent results with this technique, with a redislocation rate of 5%. Subsequently, Adachi et al.17 published a series of 20 patients with no redislocations.

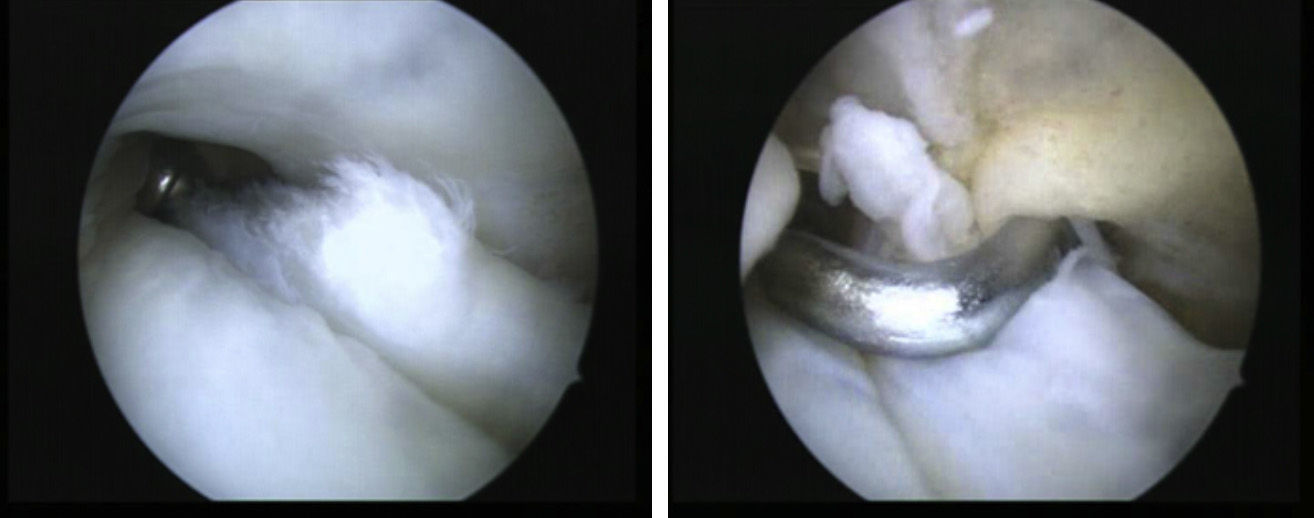

Undoubtedly, deepening of the retromalleolar groove is the most common tendoscopic technique. The periosteum is debrided using a vaporizer or synoviotome and the retromalleolar groove is deepened using a 4.0 or 4.5mm round mill (Fig. 7). The advantages of the tendoscopic technique are unquestionable, since, in addition to being a minimally invasive method with few neurovascular complications and morbidity, it allows an early return to sports activities and also favors a dynamic evaluation of the tendons and the ruling out of associated tendon ruptures. Therefore, this will also be the treatment of choice in cases of type A intra-sheath dislocations.

ConclusionsTendoscopy is a demanding and emerging technique for the management of peroneal tendon pathology. Its implementation and indications have been increasing in recent years, offering excellent clinical and functional results with few complications.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bravo-Giménez B, García-Lamas L, Jiménez-Díaz V, Llanos-Alcázar LF, Vilá-Rico J. Tendoscopia de los peroneos: nuestra experiencia. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:268–75.