To quantify the risk of dorsal innervation injury when performing direct metacarpophalangeal joint portals of the second to fifth fingers.

Material and methodAn anatomical study of 11 upper limbs of fresh corpses was carried out. After placing them in a traction tower, the metacarpophalangeal portals were developed on both sides of the extensor tendon. The dorsal sensory branches were dissected, and the distances between the portal and the nearest nerve were measured by a digital calliper. The portals of all the fingers were compared globally to assess the safest finger, and two to two radial and ulnar portals were compared in each of the fingers to assess the safest portal within each finger.

ResultsThe overall comparison of all portals and fingers showed that the third finger is the safest in any of its portals, while the ulnar side of the second and radial of the fourth are the portals with the highest risk of nerve injury (P=8.96×10−5). Comparison two to two of the radial and ulnar portals in each of the fingers showed that the ulnar portal is safer than the radial on the fourth finger (P=0.042), while the radial is safer than the ulnar on the fifth finger (P=0.003).

ConclusionsThe third finger was the safest to perform metacarpophalangeal portals, while the ulnar side of the second finger and radial side of the fourth had the highest risk of nerve injury.

Cuantificar el riesgo de lesión de la inervación dorsal al realizar portales directos de la articulación metacarpofalángica del segundo al quinto dedo.

Material y métodoSe realizó un estudio anatómico de 11 extremidades superiores de cadáveres frescos.

Tras colocarlos en torre de tracción, se realizaron los portales metacarpofalángicos a ambos lados del tendón extensor. Se disecaron las ramas sensitivas dorsales y se midieron las distancias entre el portal y el nervio más cercano mediante un calibrador digital.

Se compararon de forma global los portales de todos los dedos para valorar el dedo más seguro y se compararon dos a dos los portales radial y ulnar en cada uno de los dedos, para valorar el portal más seguro dentro de cada dedo.

ResultadosLa comparación global de todos los portales y dedos mostró que el tercer dedo es el más seguro en cualquiera de sus portales, mientras que el lado ulnar del segundo y radial del cuarto son los que tienen riesgo más alto de lesión nerviosa (p=8,96×10−5).

La comparación dos a dos de los portales radial y ulnar en cada uno de los dedos mostró que el portal ulnar en más seguro que el radial en el cuarto dedo (p=0,042), mientras que el radial es más seguro que el ulnar en el quinto dedo (p=0,003).

ConclusionesEl tercer dedo fue el más seguro para la realización de los portales metacarpofalángicos, mientras que el lado ulnar del segundo dedo y el lado radial del cuarto son los de más alto riesgo de lesión nerviosa.

Since it began in the 1960s, arthroscopy has evolved exponentially with optimisation of the size and quality of the optics, light sources and arthroscopy towers. Surgeons have simultaneously persisted in pursuing the challenge to perform arthroscopies in increasingly smaller joints and it is even possible nowadays to perform them in joints as small as the metacarpophalanges (MPs).

Despite the fact that this technique is not yet widespread, there is a significant number of MP joint pathologies indicated for being treated arthroscopically, including inflammatory arthropathies, the removal of loose bodies, joint fractures and ligament injuries.1

Similar to the widely studied dorsal portals of wrist arthroscopy,2 MP portals are not risk-free. As far as we are aware, no study exists on the safety of the MP dorsal portals of the second to fifth fingers, in relation to nerve injuries.

The purpose of this study was to quantify the risk of nerve injury by assessing the safety of MP dorsal portals of the second to fifth fingers under the positioning and traction conditions used during this technique.

Material and methodAn anatomical study of 11 upper limbs of fresh corpses from the Body Donation Centre and the dissection rooms of the Faculty of Medicine of the Complutense University of Madrid was conducted. The study was approved and developed within the UCM920547 research group. The medical records of all the corpses were available, and none had any background of trauma or surgery or obvious limb pathologies.

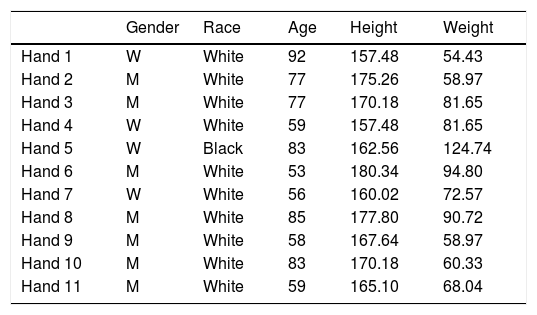

Demographic data are shown in Table 1. 36.36% (4/11) were female limbs, whilst 63.64% (7/11) were male. 90.9% (10/11) were white and 9.1% (1/11) were black. The mean age was 77.7 (53–92). Mean height and weight were 167.63cm (157.48–180.34) and 86.43kg (54.43–124.74).

Demographic data of the 11 limbs.

| Gender | Race | Age | Height | Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand 1 | W | White | 92 | 157.48 | 54.43 |

| Hand 2 | M | White | 77 | 175.26 | 58.97 |

| Hand 3 | M | White | 77 | 170.18 | 81.65 |

| Hand 4 | W | White | 59 | 157.48 | 81.65 |

| Hand 5 | W | Black | 83 | 162.56 | 124.74 |

| Hand 6 | M | White | 53 | 180.34 | 94.80 |

| Hand 7 | W | White | 56 | 160.02 | 72.57 |

| Hand 8 | M | White | 85 | 177.80 | 90.72 |

| Hand 9 | M | White | 58 | 167.64 | 58.97 |

| Hand 10 | M | White | 83 | 170.18 | 60.33 |

| Hand 11 | M | White | 59 | 165.10 | 68.04 |

Age expressed in years, height in centimetres and weight in kilograms.

M: man; W: woman.

Dissections were made with magnifying spectacles ×2.5 magnification by the main researcher. The procedure began with careful resection of the skin on the MP joints of the second to the fifth fingers. The skin size we decided to resect was 2×6cm, sufficient to expose the MP joints but not wide enough to alter the original direction of the dorsal innervations. After this, the fatty tissue and superficial fascia were resected, maintaining dorsal innervations in their position and the extensor tendons. The soft tissues surrounding the nerves were not altered to ensure no variation of their original position.

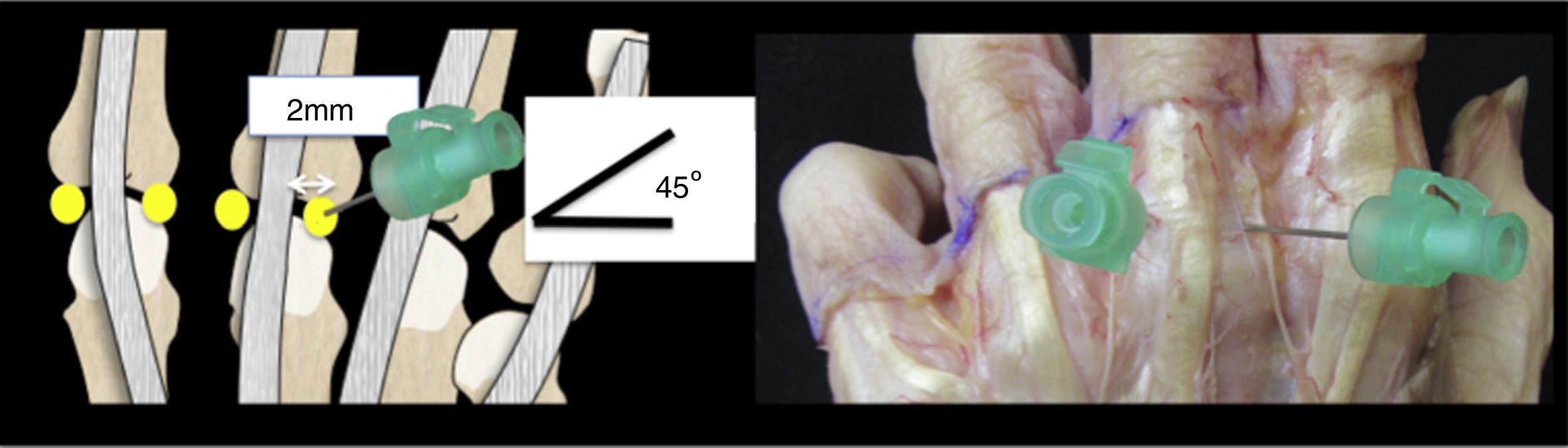

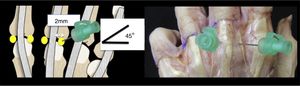

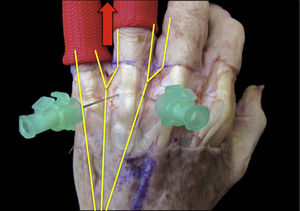

Once dissection had been made, the hands were placed in an AcuWrist® (Acumed, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA) wrist arthroscopy traction tower, with a traction of 5–10pounds. Two portals were used, in keeping with the recommended technique,1,3 with the aid of an intramuscular (IM)) injection (19gauge) on both sides of the common extensor tendon of the second to fifth fingers, in the recess areas 2mm to each side of the tendon, at 45° towards the middle line (Fig. 1).

To assess the safety of the second and third finger portals, the traction was positioned in the second and third fingers. To study the fourth and fifth finger portals, traction was positioned on the fourth and fifth fingers.

In order to simplify the nomenclature of the dorsal innervations of the hand, numbering is used so that the most radial branch of the first finger is called D1R, whilst the most ulnar is D1U and so on and so forth successively (D2R, D2U, etc.).4

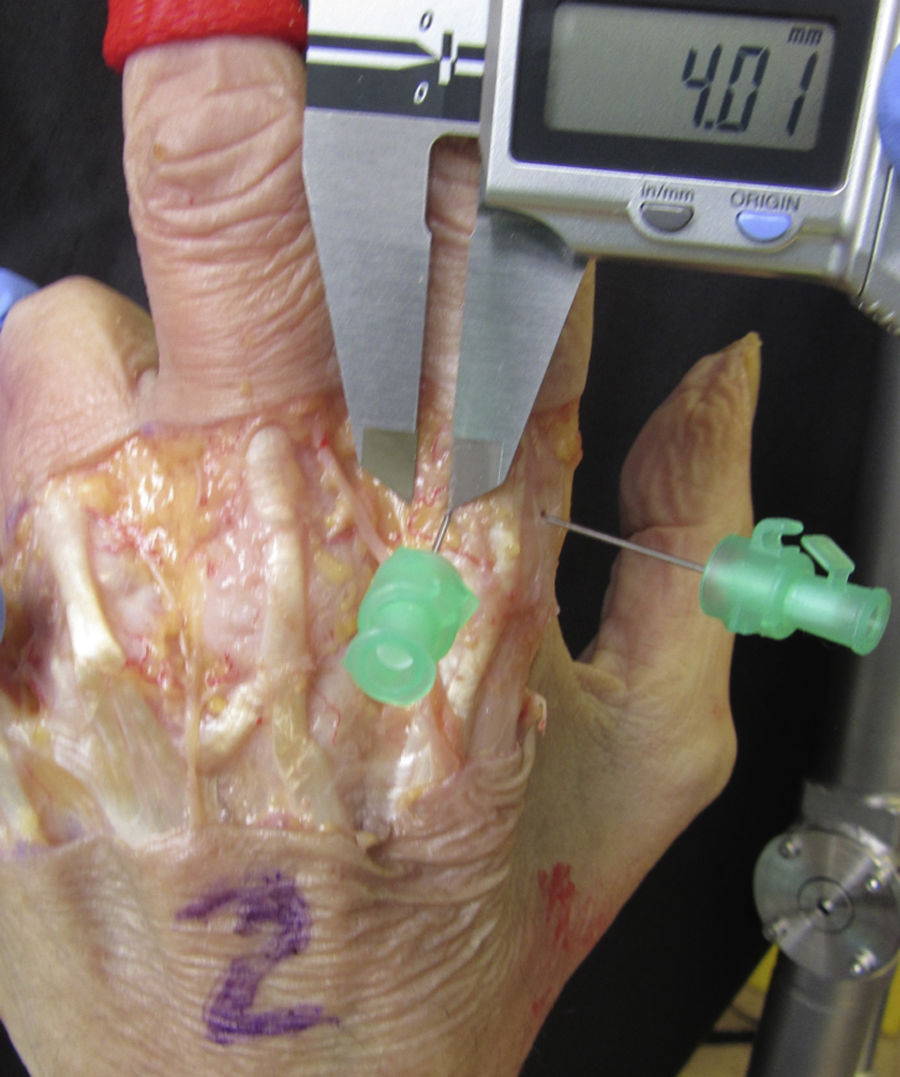

To assess the risk of nerve injury in each portal, we measured the lower distance of each portal to its adjacent nerve. All the measurements were made by the main researcher using a digital calibrator called the Absolute Digital Calliper® (0.02mm precision, Mitutoyo, Kanagawa, Japan) and supervised by a second researcher (Fig. 2).

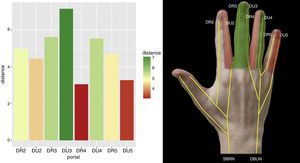

To assess the safety of the portals, distances defined as high risk, medium risk and low risk were taken. These distances were: (a) high risk, under 3.5mm; (b) medium risk, 3.5–4.5mm, and (c) low risk, over 4.5mm. They were taken with the consideration that an arthroscope sheath of 2.4mm is 3mm, and therefore distances of under half a millimetre more than the size of the sheath were considered to be high risk.

Software R for Mac (version 3.4.0; R, Vienna, Austria) was used for statistical analysis.

Due to the low sample size and the fact that the values analysed did not follow any normal distribution, non-parametric statistical tests were used. Values were expressed in terms of median and interquartile range (IQR).

To complete the two to two comparison of the radial and ulnar portals of each finger, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. No correction was applied to statistical significance, and this statistical significance was established at a value of p<0.05.

To carry out overall comparison of the radial and ulnar portals of all the fingers analysed in the study, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. For this test, statistical significance was also established at a value of p<0.05.

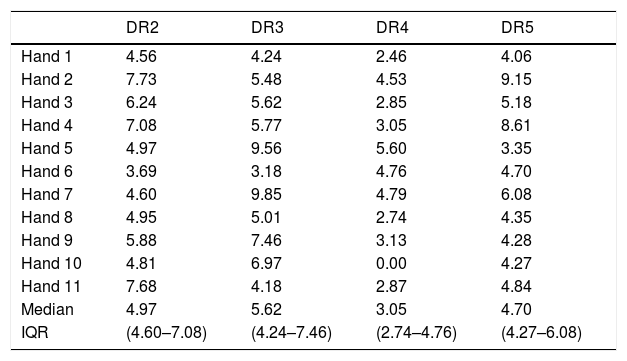

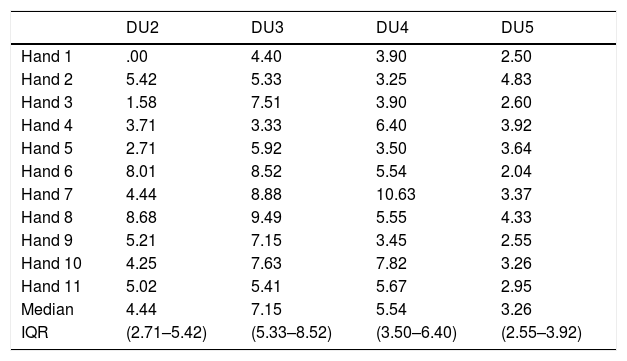

ResultsThe result of the measurements of all the specimens is contained in Tables 2 and 3.

Distance measured in millimetres from the radial portal to the collateral nerve of the second to fifth fingers. Medians and IQRs of the distance from the radial portal to the collateral nerve of the second to fifth fingers.

| DR2 | DR3 | DR4 | DR5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand 1 | 4.56 | 4.24 | 2.46 | 4.06 |

| Hand 2 | 7.73 | 5.48 | 4.53 | 9.15 |

| Hand 3 | 6.24 | 5.62 | 2.85 | 5.18 |

| Hand 4 | 7.08 | 5.77 | 3.05 | 8.61 |

| Hand 5 | 4.97 | 9.56 | 5.60 | 3.35 |

| Hand 6 | 3.69 | 3.18 | 4.76 | 4.70 |

| Hand 7 | 4.60 | 9.85 | 4.79 | 6.08 |

| Hand 8 | 4.95 | 5.01 | 2.74 | 4.35 |

| Hand 9 | 5.88 | 7.46 | 3.13 | 4.28 |

| Hand 10 | 4.81 | 6.97 | 0.00 | 4.27 |

| Hand 11 | 7.68 | 4.18 | 2.87 | 4.84 |

| Median | 4.97 | 5.62 | 3.05 | 4.70 |

| IQR | (4.60–7.08) | (4.24–7.46) | (2.74–4.76) | (4.27–6.08) |

DR2: dorsal radial nerve of the second finger; DR3: dorsal radial nerve of the third finger; DR4: dorsal radial nerve of the fourth finger; DR5: dorsal radial nerve of the fifth finger; IQR: interquartile range.

Distance measured in millimetres from the ulnar portal to the collateral nerve of the second to fifth fingers. Medians and IQRs of the distance from the ulnar portal to the collateral nerve of the second to fifth fingers.

| DU2 | DU3 | DU4 | DU5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand 1 | .00 | 4.40 | 3.90 | 2.50 |

| Hand 2 | 5.42 | 5.33 | 3.25 | 4.83 |

| Hand 3 | 1.58 | 7.51 | 3.90 | 2.60 |

| Hand 4 | 3.71 | 3.33 | 6.40 | 3.92 |

| Hand 5 | 2.71 | 5.92 | 3.50 | 3.64 |

| Hand 6 | 8.01 | 8.52 | 5.54 | 2.04 |

| Hand 7 | 4.44 | 8.88 | 10.63 | 3.37 |

| Hand 8 | 8.68 | 9.49 | 5.55 | 4.33 |

| Hand 9 | 5.21 | 7.15 | 3.45 | 2.55 |

| Hand 10 | 4.25 | 7.63 | 7.82 | 3.26 |

| Hand 11 | 5.02 | 5.41 | 5.67 | 2.95 |

| Median | 4.44 | 7.15 | 5.54 | 3.26 |

| IQR | (2.71–5.42) | (5.33–8.52) | (3.50–6.40) | (2.55–3.92) |

DU2: dorsal ulnar nerve of the second finger; DU3: dorsal ulnar nerve of the third finger; DU4: dorsal ulnar nerve of the fourth finger; DU5: dorsal ulnar nerve of the fifth finger; IQR: interquartile range.

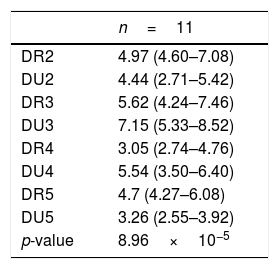

The medians (IQR) of distances from the radial portal to the radial dorsal nerve in the second to fifth fingers were 4.97 (4.60–7.08), 5.62 (4.24–7.46), 3.05 (2.74–4.76) and 4.70 (4.27–6.08) mm, respectively.

The medians (IQR) of distances from the ulnar portal to the radial ulnar nerve in the second to fifth fingers were 4.44 (2.71–5.42), 7.15 (5.33–8.52), 5.54 (3.50–6.40) and 3.26 (2.55–3.92) mm, respectively.

Direct damage occurred to the digital dorsal nerve in two measurements: one in the ulnar portal of the second finger and the other in the radial portal of the fourth finger.

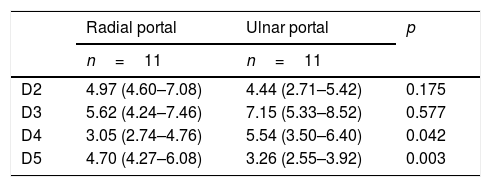

The two to two comparisons of the radial and ulnar portals in each of the fingers using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test show that in terms of digital dorsal nerve distance, the ulnar portal is safer than the radial portal in the fourth finger (p=0.042), whilst the radial portal is safer than the ulnar portal in the fifth finger (p=0.003). However, due to the small size of the sample used, we found there were no significant differences between both portals in the second finger (p=0.175) or the third finger (p=0.577) (Table 4).

Two to two comparison of the radial portals and ulnar portals in each of the fingers using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

| Radial portal | Ulnar portal | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=11 | n=11 | ||

| D2 | 4.97 (4.60–7.08) | 4.44 (2.71–5.42) | 0.175 |

| D3 | 5.62 (4.24–7.46) | 7.15 (5.33–8.52) | 0.577 |

| D4 | 3.05 (2.74–4.76) | 5.54 (3.50–6.40) | 0.042 |

| D5 | 4.70 (4.27–6.08) | 3.26 (2.55–3.92) | 0.003 |

D2: second finger; D3: third finger; D4: fourth finger; D5: fifth finger; n: number of corpses.

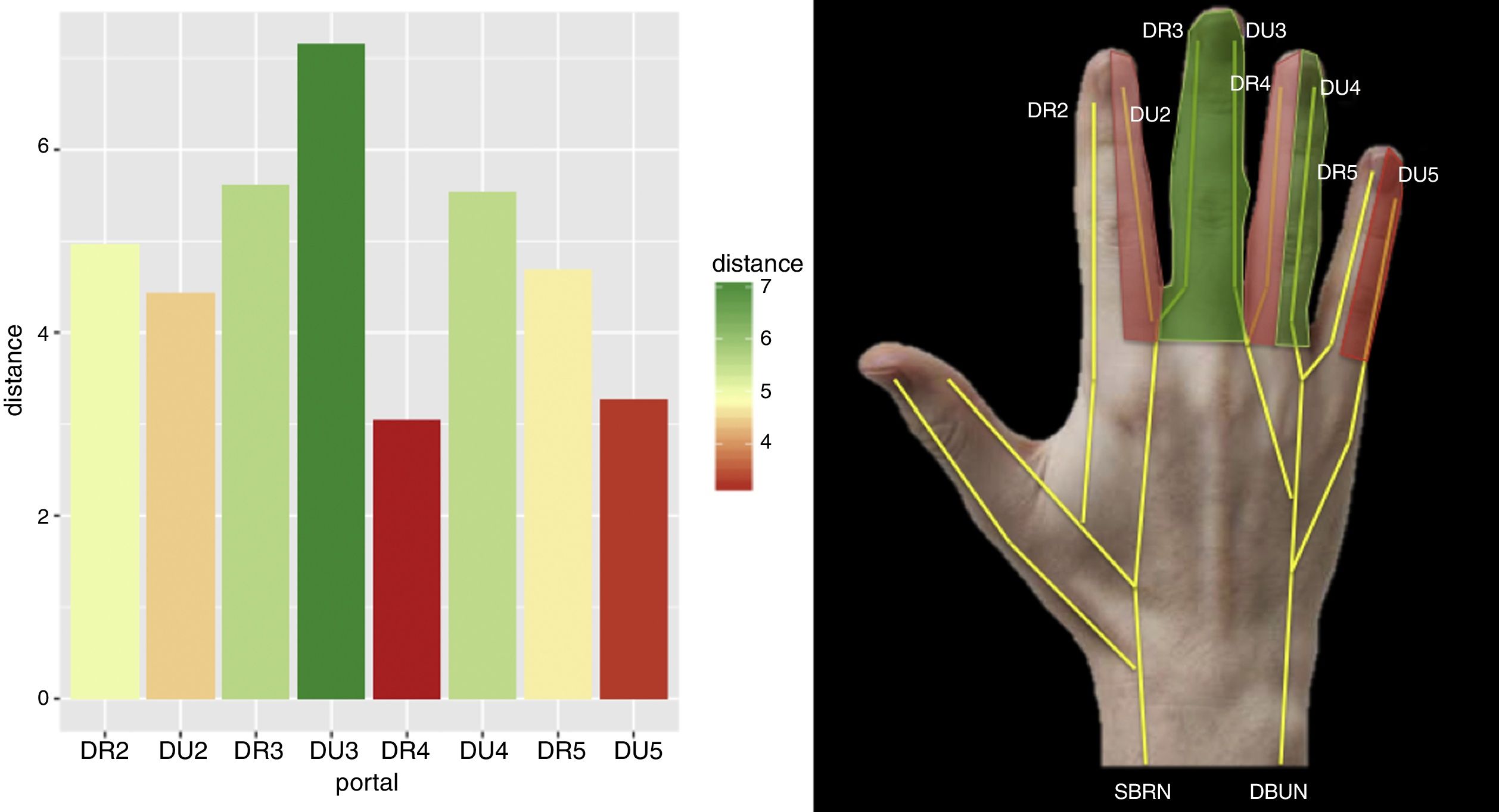

Lastly, the overall comparison of all the portals and fingers using the Kruskal–Wallis test shows that, in terms of distance to the collateral nerve, the third finger is the safest in any of its portals, with the radial portal of the fourth finger and the ulnar of the fifth finger those with the greatest risk of presenting damage (p=8.96×10−5) (Table 5).

Overall comparison of all portals and fingers using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

| n=11 | |

|---|---|

| DR2 | 4.97 (4.60–7.08) |

| DU2 | 4.44 (2.71–5.42) |

| DR3 | 5.62 (4.24–7.46) |

| DU3 | 7.15 (5.33–8.52) |

| DR4 | 3.05 (2.74–4.76) |

| DU4 | 5.54 (3.50–6.40) |

| DR5 | 4.7 (4.27–6.08) |

| DU5 | 3.26 (2.55–3.92) |

| p-value | 8.96×10−5 |

DR2: dorsal radial nerve of the second finger; DR3: dorsal radial nerve of the third finger; DR4: dorsal radial nerve of the fourth finger; DR5: dorsal radial nerve of the fifth finger; IQR: interquartile range.

DU2: dorsal ulnar nerve of the second finger; DU3: dorsal ulnar nerve of the third finger; DU4: dorsal ulnar nerve of the fourth finger; DU5: dorsal ulnar nerve of the fifth finger; n=number of corpses

After the anatomical study, we were able to conclude that according to the data obtained, the third finger is the safest for MP portals, whilst the ulnar portal of the second finger (DU2) and the radial portal of the fourth finger (DR4) are those of the greatest risk. In two to two comparison, the ulnar portal (DU4) is safer than the radial portal (DR4) in the fourth finger and the radial portal (DR5) is safer than the ulnar portal (DU5) in the fifth finger. In the second and third fingers, statistically no significant differences were found in the safety of two to two portal comparison.

MP arthroscopy continues to be a rarely used technique today. This is probably due to the low number of either clinical or anatomical publications on it. However, the use of arthroscopy in different MP joint pathologies has been described,1,5,6 particularly in rheumatology.3,7

From an arthroscopic viewpoint, both from the radial portal and the ulnar dorsal portal of the MI joints, an excellent internal vision is obtained.8 Constant anatomical points of references have been defined in MP joints.9

There are major benefits to arthroscopy in small joints compared with open surgery and they are widely developed. One of the main benefits with regard to soft tissue is the reduction of post-surgical stiffness and this is one of the most common complications in open MP surgery.

Although MP arthroscopy is an appealing technique with major benefits, it is not exempt from complications.

When making MP portals, both ulnar and radial, we use the extensor tendon as an anatomical reference, and the possibility of injury of it is low. Even so, this is one of the most feared complications in the literature.10 Injury of the neurovascular bundles could be considered to be the most important complication when developing MP portals, since there are no constant references to its location.

After studying the four different joints of the 11 limbs, a direct injury of the digital dorsal nerve occurred on two occasions. The nerves in which the injury occurred were values outside the range or outliers and therefore not included in the statistical study, but we should take them into consideration from a clinical viewpoint.

Taking into consideration the medians of the distances in each portal and with the distinction between the low, medium and high risk of each portal, a coloured map may be drawn on the back of the hand to reflect the risk of nerve injury (Fig. 3).

In order to take the measurements in the most similar conditions to clinical practice, the hand was placed in traction using a standard traction tower. To study the second and third fingers both were subjected to a traction force of 5–10pounds, and the fourth and fifth fingers were studied in a similar manner.

Some authors defend horizontal traction in MP arthroscopy because it is more ergonomic and helps with the use of fluoroscope.11 However, other authors consider, like us, that traction should be zenithal.5,12

The third finger is the one which draws the wrist axis, and MP articulation of the third finger is therefore the one which is most in line with the wrist on traction. This may be one of the reasons why measurements made on this articulation are the safest. When performing traction of the third finger in alignment, the soft tissues including the neurovascular bundle may likely be lateralised, moving away from the arthroscopic portals and this may explain the results. Another explanation for the results could be the dorsal innervation pattern of each limb studied. According to anatomic studies,13–15 the most common innervation pattern in the third finger is divided between radial nerve branches and cubital nerve branches. This innervation could mean that nerves are more lateralised and therefore more distant from the arthroscopic portal performance area.

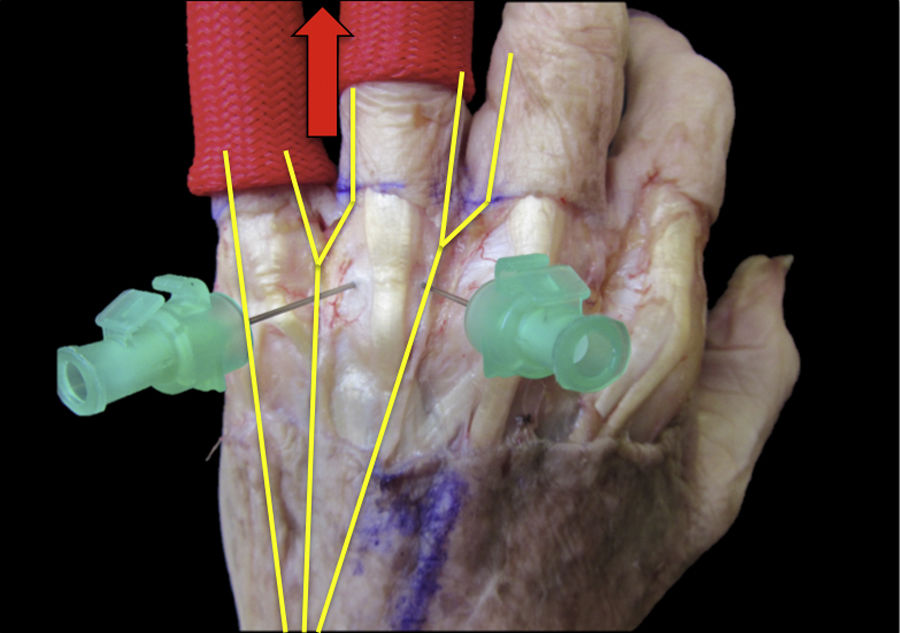

Two to two comparison of the radial and ulnar portals in each of the fingers only resulted in significant outcomes in the fourth and fifth fingers. The radial of the fourth finger (DR4) and the ulnar of the fifth finger (DU5) were safer than the ulnar of the fourth finger (DU4) and the radial of the fifth finger (DR5). Bearing in mind the type of traction performed for the fourth and fifth finger, one of the explanations for these results could also be related to the innervation pattern. The common cubital trunk which innervates DU4 and DR5 is the one most centred in the traction axis of the fourth and fifth fingers. It is thus possible that the neurovascular bundles are lateralised, as was previously mentioned regarding the third finger (Fig. 4).

One of the limitations of our study is the possible influence of the different dorsal innervation patterns of the hand and wrist in the distance of the nerve from the arthroscopy portals. The most commonly described innervation pattern was considered. Innervation of the first, second and radial regions of the third finger by the sensitive branch of the radial nerve and the ulnar edge of the third, fourth and fifth fingers by the sensitive branch of the cubital nerve.13–15 It is possible that different innervation patterns would reflect different results from those we obtained.

We decided to resect the dorsal skin prior to developing the portals, to ensure their constancy and taking as visual reference the extensor tendon. It was thus possible to assess the results eliminating the bias of the appropriate or poor development of the arthroscopy portal. Even so, particular care was taken not to move the adjacent tissues to the digital dorsal nerves so as not to vary their position.

Despite the study limitations, we consider that the results obtained are of great use. This is the first anatomical work which studies the risk of nerve injury with the MP arthroscopic portals and serves as a reference when performing this surgical technique, with care to be taken as a precaution when developing MP portals. We would recommend not directly developing portals, particularly on the radial side of the second finger and the ulnar side of the fourth finger.

ConclusionsMP arthroscopy is not a widely used technique but has the potential for the treatment and diagnosis of different MP pathologies. MP arthroscopy may possibly become the standard procedure for diagnosis and treatment over the next few years.

MP dorsal portals are not free from complications, just as no surgical technique is. The risk of nerve injury is important if the portals are directly developed.

Anatomical knowledge and nerve distribution are essential.

The third finger is the safest for MP portal development, whilst the ulnar side of the second finger (DU2) and the radial side of the fourth finger (DR4) are with the highest risk of nerve injury.

Ethical liabilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed comply with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation, the World Medial Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Limousin B, Corella F, del Campo B, Fernández E, Corella MÁ, Ocampos M, et al. Seguridad de los portales metacarpofalángicos. Estudio anatómico. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:380–386.