To evaluate the percentage of complications associated with ankle and hindfoot arthroscopy in our hospital and to compare the results with those reported in the literature.

Material and methodA retrospective descriptive review was conducted on the complications associated with ankle and hindfoot arthroscopy performed between May 2008 and April 2013. A total of 257 arthroscopy were performed, 23% on subtalar joint, and 77% of ankle joint. An anterior approach was used in 69%, with 26% by a posterior approach, and the remaining 5% by combined access.

ResultsA total of 31 complications (12.06%) were found. The most common complication was neurological damage (14 cases), with the most affected nerve being the superficial peroneal nerve (8 cases). Persistent drainage through the portals was found in 10 cases, with 4 cases of infection, and 3 cases of complex regional pain syndrome type 1.

DiscussionThere have been substantial advances in arthroscopy of ankle and hindfoot in recent years, expanding its indications, and also the potential risk of complications.

The complication rate (12.06%) found in this study is consistent with that described in the literature (0–17%), with neurological injury being the most common complication.

ConclusionsAnkle and hindfoot arthroscopy is a safe procedure. It is important to make a careful preoperative planning, to use a meticulous technique, and to perform an appropriate post-operative care, in order to decrease the complication rates.

Evaluar el porcentaje de complicaciones asociadas con la artroscopia de tobillo y retropié en nuestro centro y comparar nuestros resultados con aquellos publicados en la literatura.

Material y métodoRealizamos un estudio descriptivo retrospectivo de las complicaciones asociadas con las artroscopias de tobillo y retropié realizadas entre mayo del 2008 y abril del 2013. Se revisaron 257 artroscopias, un 23% de subastragalina y un 77% de tobillo. El acceso empleado fue anterior en el 69%, posterior en el 26% y combinado en el 5% restante.

ResultadosSe recogieron 31 complicaciones (12,06%), siendo la complicación más frecuente la lesión neurológica (14 casos) y el nervio más afectado el nervio peroneo superficial (8 casos). Observamos 10 casos de drenaje persistente a través de los portales, 4 casos de infección y 3 casos de síndrome de dolor regional complejo tipo 1.

DiscusiónLos avances en la artroscopia de tobillo y retropié, y el aumento de sus indicaciones, conllevan un aumento del riesgo potencial de complicaciones.

La tasa de complicaciones reflejada en nuestro análisis (12,06%) es comparable con lo descrito en la literatura (0-17%), siendo la complicación más frecuente la lesión neurológica.

ConclusionesLa artroscopia de tobillo y retropié es un procedimiento seguro. Es importante realizar una cuidadosa planificación preoperatoria, utilizar una técnica meticulosa y realizar un cuidado postoperatorio apropiado para disminuir la tasa de complicaciones.

Arthroscopic surgery of the foot and ankle has seen major advances since its infancy in 1972, which have significantly extended its indications.

The arthroscopic technique enables direct visualisation of the intra-articular structures without the need for extensive approaches, which helps to reduce morbidity and postoperative pain. Furthermore, it has several advantages compared to conventional surgery, such as: reduced postoperative pain, reduced hospital stay associated with the procedure and rehabilitation, and an earlier return to routine activities.

However, as with any surgical procedure, it is not free from complications, the most common being neurological injury.

The objective of this study is to assess the percentage of complications associated with ankle and hindfoot arthroscopy in our series, and compare the outcomes with those published in the literature.

Material and methodWe present a retrospective, descriptive study of ankle and hindfoot arthroscopies performed in our hospital between May 2008 and April 2013.

Information was gathered on the patients’ demographic data, diagnoses, arthroscopic procedures undergone, duration of follow-up and complications.

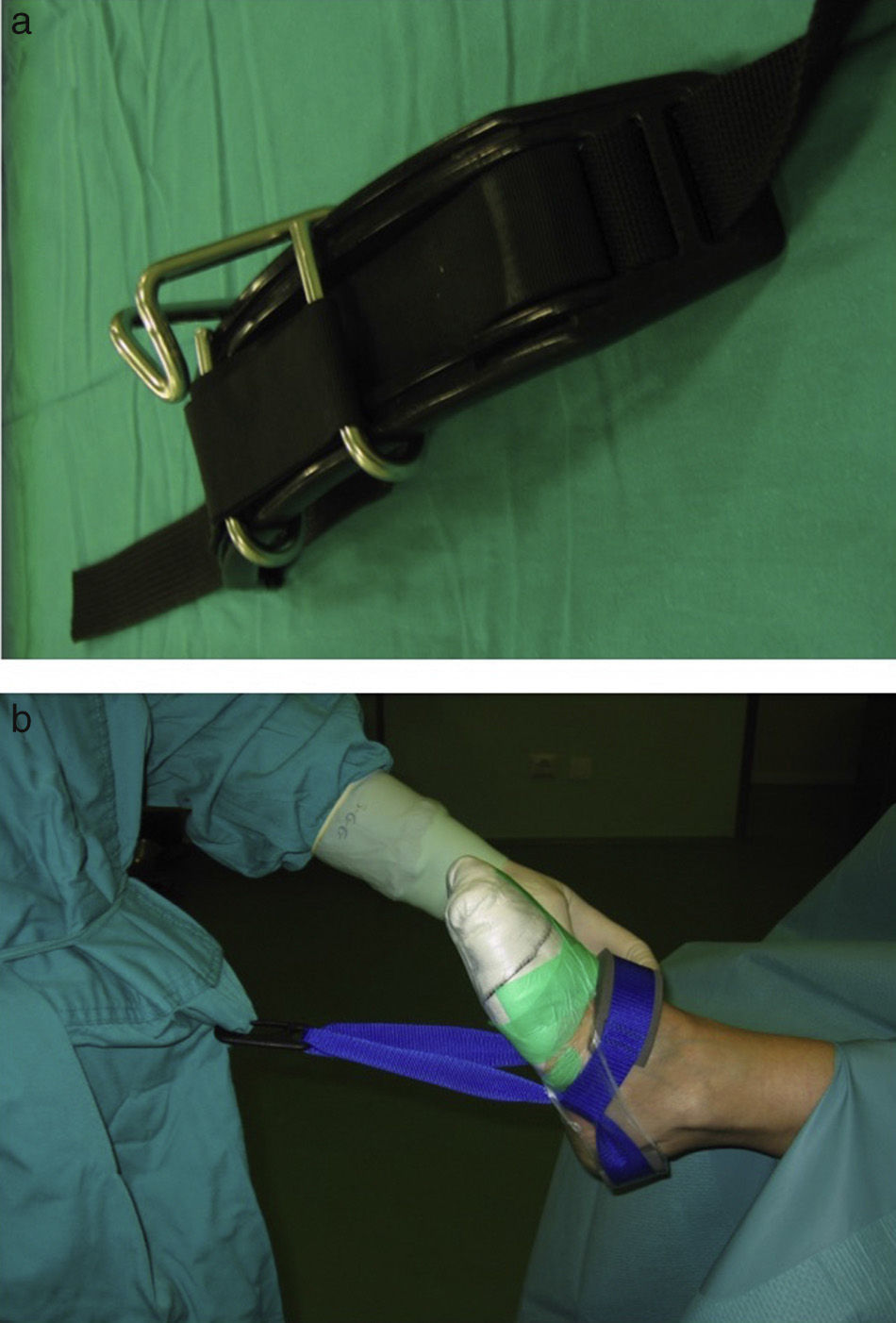

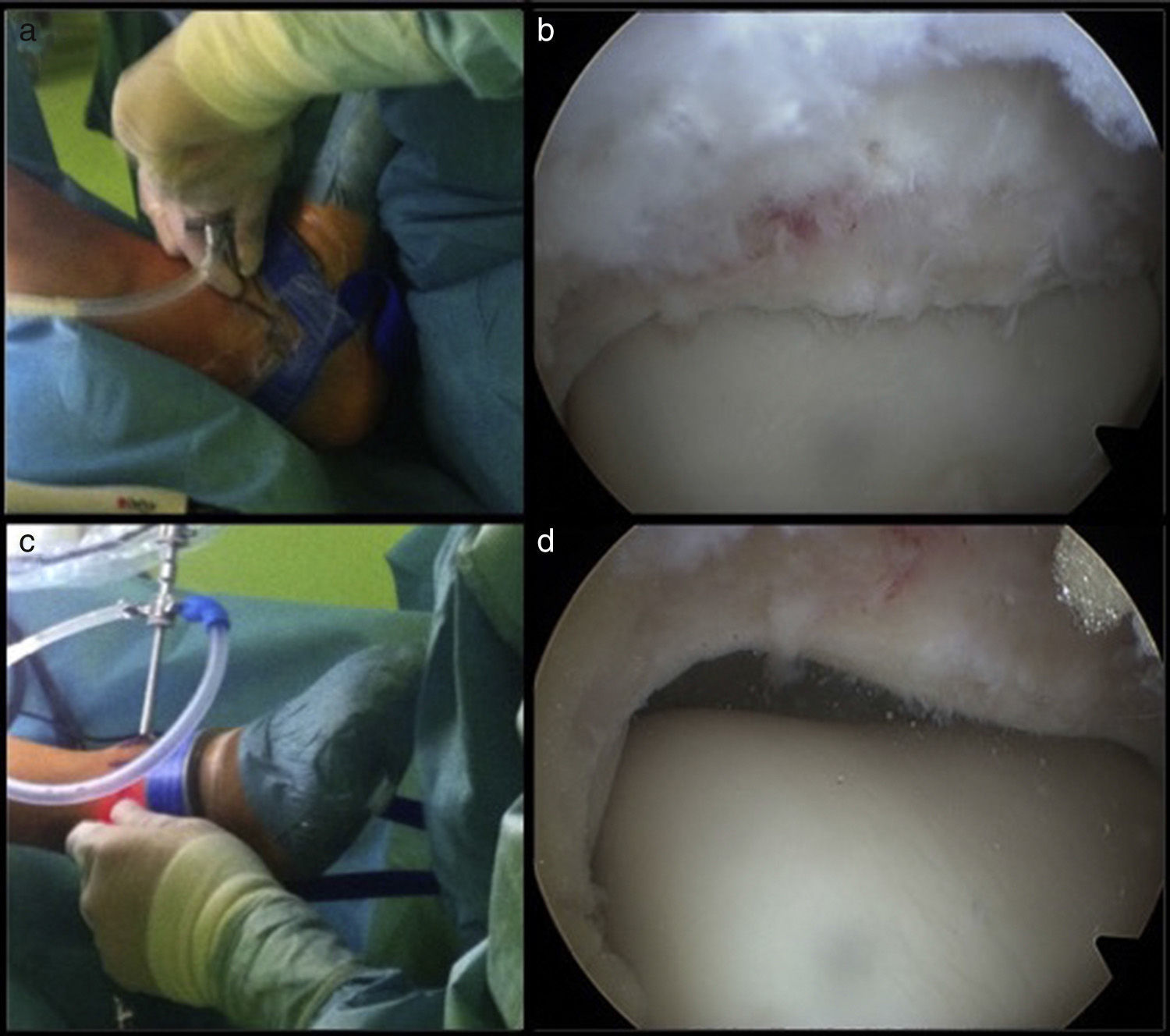

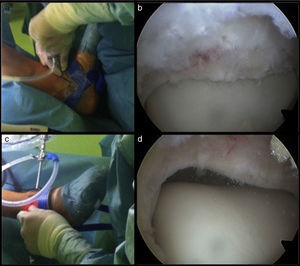

With regard to surgical technique, ischaemia at the root of the lower limb and intermittent non-invasive traction were used in all cases, at the discretion of the surgeon. We used a Guhl ankle distraction strap for the traction (Smith & Nephew Inc., Andover, MA 01810, USA), anchored to a harness placed by the surgeon under the sterile gown (Fig. 1).

In arthroscopies using an anterior approach, we placed the patient in the supine position. Initially we created the anteriomedial portal, just medial to the tendon of the anterior tibial muscle, coinciding with a palpable depression. After making a vertical cutaneous incision, we inserted a straight mosquito until reaching the joint, and then inserted the sheath of the arthroscope with the ankle in dorsiflexion, to prevent iatrogenic injury to the articular cartilage. We then created the anterolateral portal just lateral to the peroneus tertius or, in its absence, to the common digital extensor tendon. It is important to avoid the intermediate dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial peroneal nerve, which we identified beforehand using the fourth toe flexion sign (Fig. 2).

In the posterior arthroscopies, we placed the patient in the prone position, so that the affected foot extended over the edge of the operating table, and we used the 2-portal endoscopic approach at both sides of the Achilles tendon described by Van Dijk et al.1 With the ankle in neutral flexion we marked the medial and lateral edges of the Achilles tendon and the tip of fibula. We traced a straight line from the tip of fibula, parallel to the sole of the foot. We created the portals on this line, approximately 0.5cm at both sides of the Achilles tendon. We started with the posterolateral portal and, after making a vertical cutaneous incision, we inserted a straight mosquito in the direction of the first interdigital space, until reaching the bone. At that moment, we removed the mosquito and inserted the sheath of the arthroscope with the blunt obturator. We then created the posteromedial portal, at the same height as the posterolateral portal, approximately 0.5cm medial to the Achilles tendon, and inserted a straight mosquito so that it formed a 90° angle with the arthroscope. We proceeded until we touched the sheath of the arthroscope and we slid over it up to its distal end. Then we inserted the synovial resector through the posteromedial portal, with its teeth directed laterally, resecting fat and the joint capsule until visualising the joint.

We used a 4.5mm, 30° arthroscope.

We performed 257 arthroscopies on 215 patients, with a mean age of 41.31 years (20–62 years). Seventeen percent were female and 83% male. The mean follow-up was 10.5 months (1.4–59.1 months).

In terms of surgical technique: 77% were ankle arthroscopies and the remaining 23% subtalar joint arthroscopies.

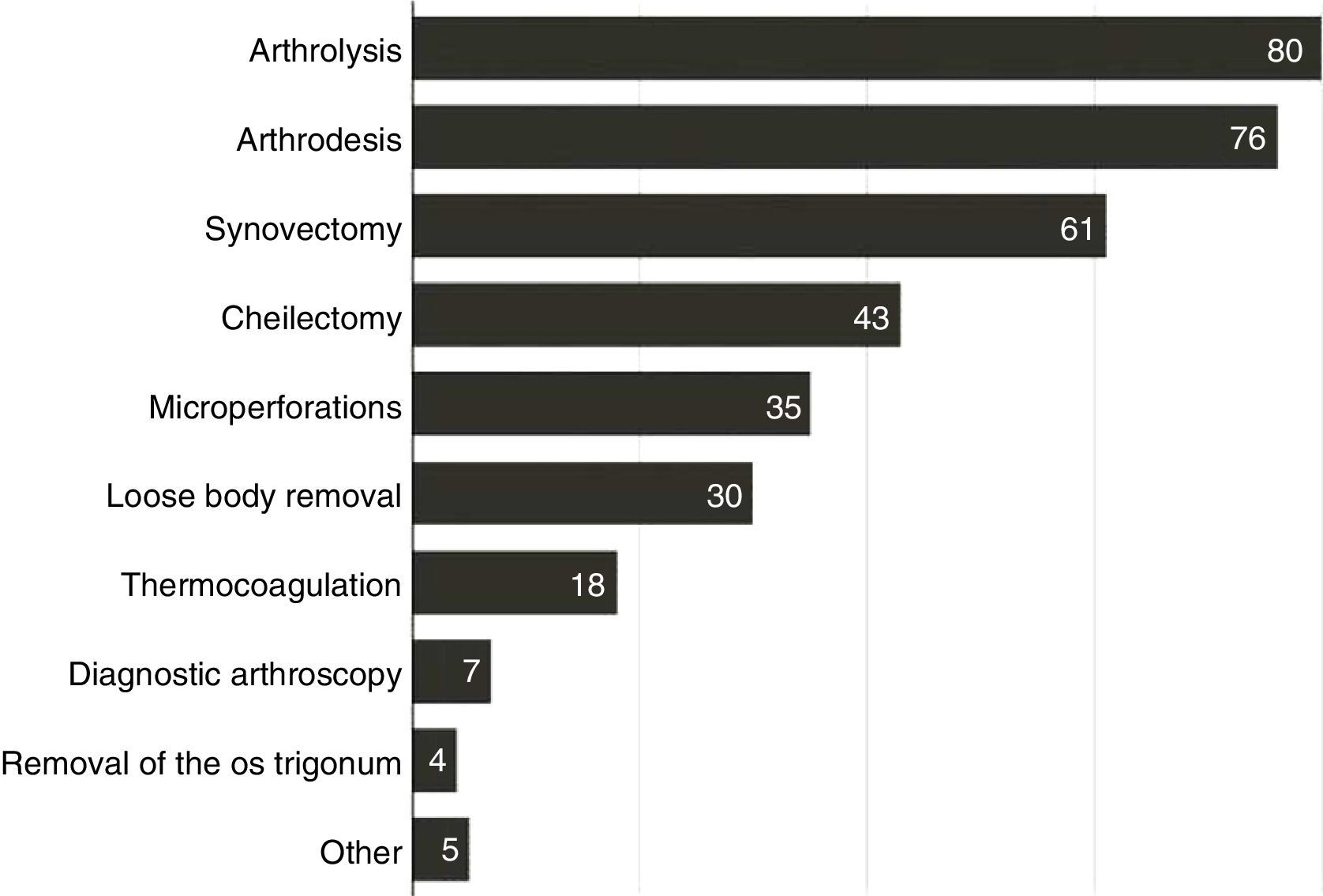

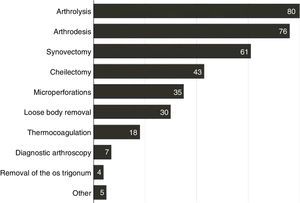

In terms of the portals used: 69% were anterior, 26% posterior and the remaining 5% combined access. The most frequent arthroscopic procedures were arthrolysis, synovectomy and cheilectomy (Fig. 3).

ResultsThe results revealed a total of 31 complications, corresponding to 12.06% of the total cases. The most common complication was neurological injury (14 cases); the peroneal nerve being most affected (8 cases). We observed three cases of injury to the deep peroneal nerve, 2 cases of injury to the sural nerve and one case of injury to the saphenous nerve. They resolved spontaneously in all cases, except in one case of damage to the superficial peroneal nerve, and the 2 cases of sural nerve injury, which required surgical revision and neurolysis. Ten cases of persistent drainage through the portals were observed, from the anterolateral portal in 7 cases, and from the anteromedial portal in 3 cases. These all resolved spontaneously within 3 weeks. We observed 2 cases of superficial infection which was resolved by empiric oral antibiotherapy, and 2 cases of deep infection by methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus which were resolved by surgical treatment with cleaning and debridement along with intravenous antibiotherapy. Three patients developed complex regional pain syndrome type one that required treatment from the Pain Unit, and which resolved in a period of between 3 to 5 months.

Twenty-three percent of these complications occurred in procedures performed by posterior arthroscopy and the remaining 77% in arthroscopies using the anterior technique. However, taken in isolation, the percentage is similar in both, 13% in anterior portals and 12% in posterior portals.

Eleven complications were observed in the arthrolysis procedures (35.4% of the total complications), 3 injuries to the deep peroneal nerve, 3 lesions to the superficial peroneal nerve, one complex regional pain syndrome type 1, one persistent suppuration through the anterolateral portal, 2 deep infections and one superficial infection. During the anterior synovectomy, we observed 5 complications (16.1%), one lesion of the superficial peroneal nerve, 3 persistent drainages through the portals, and 2 complex regional pain syndromes type 1. In the loose body removal procedures, 4 patients had problems with the portals (12.9%). Six complications (19.3%) occurred during ankle arthrodesis, 3 injuries to the superficial peroneal nerve, one saphenous nerve injury, one superficial infection, and one patient had persistent drainage through the anterolateral portal. In the subtalar joint arthroscopy procedures we observed 2 cases of sural nerve lesion (6.4%), one superficial peroneal nerve injury, and one patient had persistent drainage through the anteromedial portal.

DiscussionArthroscopy of the ankle has undergone major advances since Burman stated in 1931 that the ankle was not a suitable joint for this technique, because the joint space is too narrow.2 After the developments in instruments and techniques, the indications and complexity of procedures have broadened, increasing the potential risk of complications.

Knowledge of the superficial and intra-articular anatomy of the region of the ankle is essential, due to the proximity of the neurovascular and tendinous structures to the portals, and the consequent inherent risk of injury to them.3

Initially we recommend marking the anatomical limits, including the joint line, the anterior tibial tendon and the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve, in arthroscopies using the anterior approach. In posterior arthroscopies we should mark the Achilles tendon and the lateral malleolus, in order for the portals to be created correctly.

In order to prevent damage to neurovascular and tendinous structures, it is recommended that vertical incisions are made only on the skin, making a blunt dissection of the deepest layers with a straight mosquito and blunt obturator. The portals should not be made very close together in order to reduce the risk of cutaneous necrosis. Systematically closing the portals helps to reduce the risk of formation of cutaneous fistulae.4

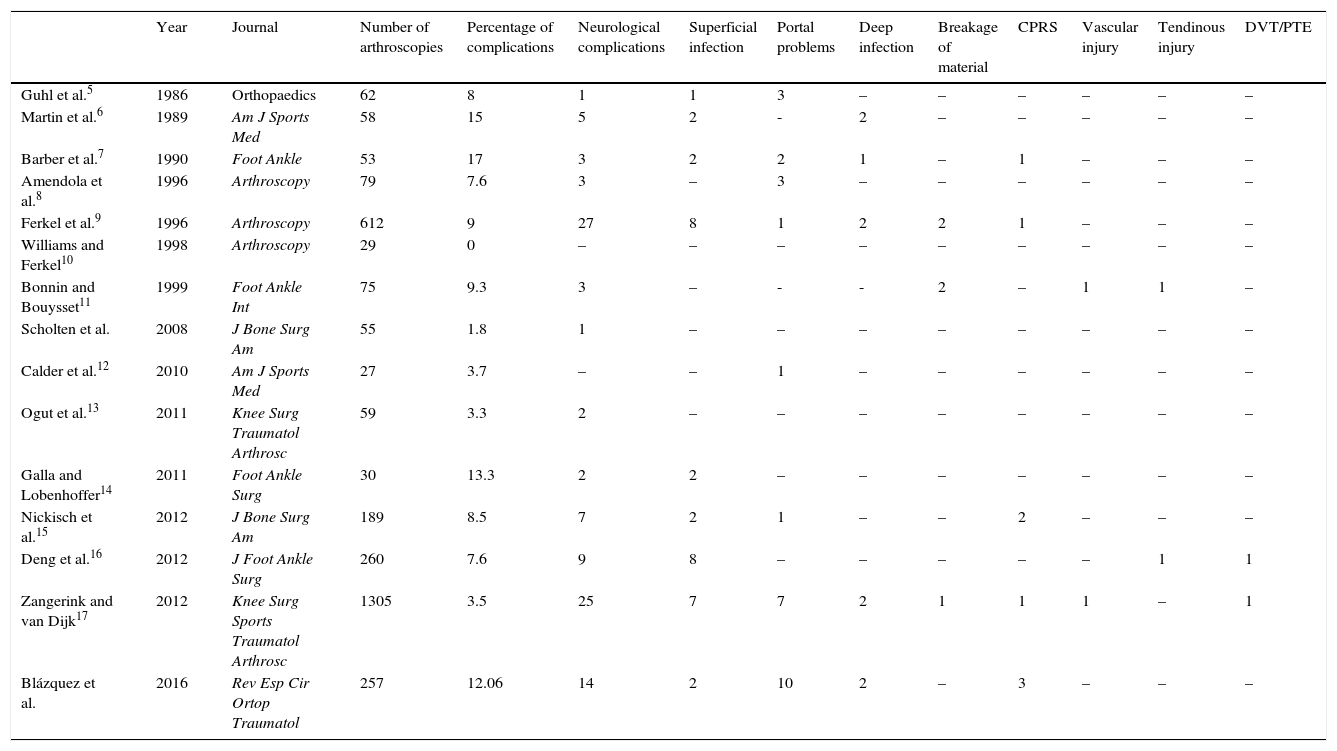

The rate of complications described in the literature varies from 0% to 17% (Table 1),5–17 the most frequent complication being neurological damage (45% of complications). Our outcomes are comparable with these data, we observed a 12.06% complication rate in our study; the most frequent being neurological damage, at 35.48% of the complications.

Complication rate of ankle and hindfoot arthroscopy published in the literature. We have added our results in the last row of the list.

| Year | Journal | Number of arthroscopies | Percentage of complications | Neurological complications | Superficial infection | Portal problems | Deep infection | Breakage of material | CPRS | Vascular injury | Tendinous injury | DVT/PTE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guhl et al.5 | 1986 | Orthopaedics | 62 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Martin et al.6 | 1989 | Am J Sports Med | 58 | 15 | 5 | 2 | - | 2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Barber et al.7 | 1990 | Foot Ankle | 53 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Amendola et al.8 | 1996 | Arthroscopy | 79 | 7.6 | 3 | – | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ferkel et al.9 | 1996 | Arthroscopy | 612 | 9 | 27 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | – | – |

| Williams and Ferkel10 | 1998 | Arthroscopy | 29 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bonnin and Bouysset11 | 1999 | Foot Ankle Int | 75 | 9.3 | 3 | – | - | - | 2 | – | 1 | 1 | – |

| Scholten et al. | 2008 | J Bone Surg Am | 55 | 1.8 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Calder et al.12 | 2010 | Am J Sports Med | 27 | 3.7 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ogut et al.13 | 2011 | Knee Surg Traumatol Arthrosc | 59 | 3.3 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Galla and Lobenhoffer14 | 2011 | Foot Ankle Surg | 30 | 13.3 | 2 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nickisch et al.15 | 2012 | J Bone Surg Am | 189 | 8.5 | 7 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 2 | – | – | – |

| Deng et al.16 | 2012 | J Foot Ankle Surg | 260 | 7.6 | 9 | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Zangerink and van Dijk17 | 2012 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | 1305 | 3.5 | 25 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 |

| Blázquez et al. | 2016 | Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol | 257 | 12.06 | 14 | 2 | 10 | 2 | – | 3 | – | – | – |

The superficial peroneal nerve was most affected in the anterior arthroscopies, to be specific, the intermediate dorsal cutaneous branch (8 cases). It has been previously recommended in the literature that its course should be marked preoperatively, due to its proximity to the anterolateral portal and its anatomical variability.17–20 It is the only visible nerve in the human body. It is easy to locate, by plantar flexion of the ankle and inversion of the foot.9,18 Stephens and Kelly described an alternative method for locating the nerve, comprising a plantar flexion sign of the 4th and 5th toes.19 It can also be located by transillumination of the skin with the arthroscope from the anteromedial portal. With dorsiflexion of the ankle the nerve moves away laterally, 2.4mm when we go from 10° plantar flexion into a neutral position, and 3.6mm when we go from 10° plantar flexion to dorsiflexion.20 Therefore we recommend creating the anterolateral portal medial to the cutaneous marking.

The sural nerve was most affected in the posterior arthroscopies (2 cases). Although it is difficult to locate by palpation or transillumination, its safety can be ensured by creating the anterolateral portal just lateral to the Achilles tendon and directing the cannula medially towards the centre of the joint.

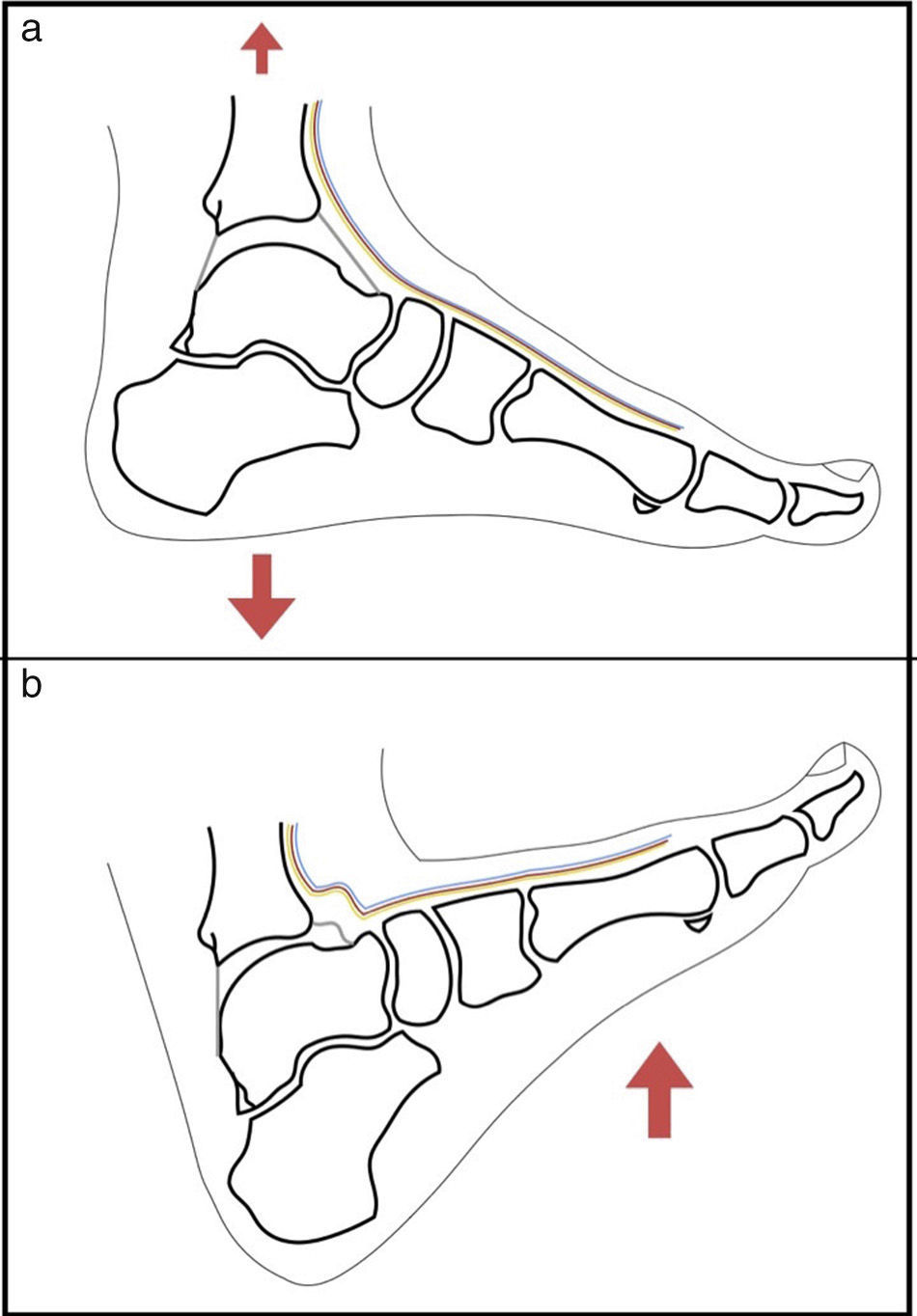

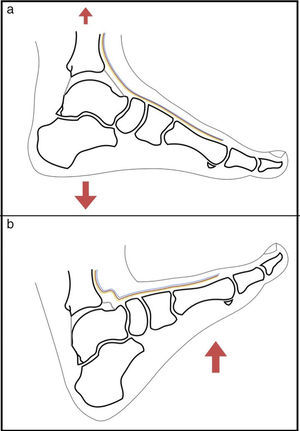

When we are working on the posterior compartment, the flexor hallucis longus tendon takes on particular relevance, since the medial neurovascular bundle runs medial to it. It is important to locate it and be aware that its lateral edge determines the safe working area.3 Another subject of debate is the use of traction. The use of traction enables almost complete visualisation of the articular surface of the talus. However, the anterior neurovascular and tendinous structures tighten, increasing the risk of iatrogenic injury when we are creating the portals or when we are working on the anterior compartment with the vaporiser or the synovial resector. By contrast, with the ankle in dorsiflexion these structures relax, enabling them to be moved away when the optic and instruments are inserted, reducing the risk of injury17,21 (Fig. 4). Moreover when fluid is put into the joint, the anterior working area enlarges, enabling injuries to be treated in the anterior region of the ankle. In addition, with the dorsiflexion of the ankle, the cartilage of the articular surface of the talus is concealed in the mortise, preventing it from becoming injured while the anterior portals are being created (Fig. 5).

The application of traction on the joint enables almost complete visualisation of the articular cartilage of the talar bone (a). By contrast, with the ankle dorsiflexed the articular cartilage is concealed, protecting it while the material is inserted, and the anterior neurovascular structures are relaxed, enabling them to be moved away during the introduction of the material, reducing the risk of injury to them (b).

Lozano-Calderón et al. conducted a review of 206 patients, 50% with traction and 50% without. They observed that non-invasive traction enabled visualisation of the deltoid ligament and the medial gutter, whereas without traction it was easier to visualise the medial gutter and the anterior compartment.22 We use intermittent non-invasive traction, reserving the use of traction only when necessary. We recommend the dorsiflexion mechanism to create the anterior portals and treat pathology in the anterior compartment, whereas we consider the use of traction to expose and treat osteochondral injuries in the posterior portion of the talus or the tibia.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, it is a descriptive, retrospective study, with the limitations that that entails. Furthermore, the design of our study does not allow comparison of the complication rates of the different surgical techniques. In addition, our patient population was very heterogeneous; many procedures had been undertaken for various diagnoses. Finally, some complications, such as iatrogenic injury to the cartilage are difficult to assess, since we do not have videos of all the operations, and therefore this has not been taken into account. This might have lead to the real number of complications being under diagnosed. However this complication has not been assessed in other studies either; therefore the complication rates in the current literature are still comparable.

ConclusionsArthroscopy of the ankle and hindfoot is a safe procedure, with reduced morbidity and recovery time compared to arthrotomy. However it is not free from complications, nerve injury being the most common.

It is important to make careful preoperative planning, to use a meticulous technique and appropriate postoperative care in order to reduce the rate of complications.

Knowledge of the anatomy of the foot and ankle is essential in order to perform the procedure safely and to prevent complications.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patients’ data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests or source of funding to declare.

Please cite this article as: Blázquez Martín T, Iglesias Durán E, San Miguel Campos M. Complicaciones tras la artroscopia de tobillo y retropié. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:387–393.