Orthopaedic procedures performed in Day Surgery Units provide important advantages which disappear when patients require admission when postoperative recovery is not as expected. The aim of this study was to analyse the reasons for unplanned hospital admissions after orthopaedic procedures in a Day Surgery Unit and their relationship between variables such as patient age, anaesthetic risk and technique, procedure or duration.

MethodsAmbispective cohort study of 5085 patients who underwent surgical orthopaedic procedures between 1995 and 2017. Thirty-nine variables provided by the Unit’s database were analysed. The database was opened on the day of admission and closed the 30th postoperative day.

ResultsOf the patients, 98.2 % were discharged from the Unit. Seventy- four, 1.5 % required overnight admission. This percentage showed significant differences in relation to the type of procedure, type of anaesthesia and duration, which conditioned overnight admission due to inadequate postoperative pain management, nausea or wound complications. Seventeen patients, .3 %, required readmission after discharge due to complications that arose at home, such as wound infection, which was the most common.

ConclusionsUnplanned admissions are more frequently related to general anaesthesia, lengthy surgeries and procedures such as arthroscopy, hallux valgus corrections or removal of osteosynthesis material. The major reasons for unplanned admissions were inadequate postoperative pain management for overnight admissions and wound infection for admissions after discharge.

Los procedimientos de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología (COT) realizados en Unidades de Cirugía Mayor Ambulatoria (CMA) ofrecen importantes ventajas que desaparecen cuando la recuperación postoperatoria no es la esperada y los pacientes precisan ingresar. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar las causas de ingresos no deseados tras intervenciones quirúrgicas de COT en una Unidad de CMA en relación con variables como edad, riesgo anestésico, tipo de anestesia, procedimiento o duración.

MétodosEstudio de cohorte ambispectivo sobre 5085 pacientes intervenidos desde 1995 a 2017. Se analizaron 39 variables proporcionadas por la base de datos de la Unidad que se abre al ingreso en la misma y se cierra el día 30 postoperatorio.

ResultadosEl 98.2% de los pacientes fueron dados de alta de la Unidad. Precisaron ingresar 74, 1.5%. Este porcentaje demostró diferencias significativas en relación al tipo de procedimiento, tipo de anestesia y duración, que condicionaron el ingreso inmediato por mal control del dolor agudo postoperatorio (DAP), náuseas o alteraciones de la herida. 17 pacientes, 0.3%, precisaron un ingreso diferido por complicaciones surgidas en el domicilio, siendo la más frecuente la infección de herida.

ConclusionesLos ingresos no deseados se relacionan con mayor frecuencia con el empleo de anestesia general, con operaciones de mayor duración y con procedimientos como la cirugía artroscópica, correcciones de hallux valgus o retiradas de material de osteosíntesis, siendo las causas de ingreso más importantes el mal control del DAP en los inmediatos y la infección de herida en los diferidos.

The percentage of patients who require hospital admission after orthopaedic surgery (OS) in major ambulatory surgery (MAS),either because they could not be discharged from the unit (immediate admission) or because after being discharged they needed to be admitted due to some type of complication (deferred admission) is a major indicator of the quality of care in MAS units.1,2

In recent reviews, the percentage of unplanned admissions after OS procedures carried out in MAS units was reported as being between .1 %3 and 2.2 %.4 Deferred admissions need to be added to these figures from emergency services or the external consultancy reviews and these range between .11 % and 1.28 % of all cases.5,6

The causes of these unplanned admissions is linked to anaesthesia, surgery, social causes or poor postoperative pain control although there is variability in publications due to the low percentage of adverse events recorded in MAS.3–7

The aim of this study was to analyse the causes which condition an immediate or deferred admission and their relationship with variables such as age, sex, physical status or anaesthetic risk according to the American Association of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) classification, the type of disease, the anaesthetic technique or the duration of the procedure.

MethodsAn observational, analytical ambispective cohort study was conducted, comprising 5085 patients operated on by the OS service in the MAS unit of the Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa de Zaragoza from when it began to function in April 1995 to March 2017. Patient selection was based on clinical or physiological criteria (patients with ASA I, II and III risk stable, without age as a limiting factor). Also psychological criteria (capable of understanding instructions) and social criteria (availability of a carer, contact telephone number, etc.), these all being standard criteria in MAS units.7,8

Davis scale type ii9 procedures were selected but also several type I procedures in patients with major physical impairment. In all cases they were programmed procedures, with a minimum risk of haemorrhaging, a duration of under 90min approximately, which would not condition prolonged immobilizations and with postoperative pain controlled by standard drugs.

The patients were discharged in keeping with modified Chung criteria,10 which assess vital signs, the ability to walk, the presence of nausea or vomiting, postoperative pain, wound status, recovery of spontaneous urinating and ability to intake liquids. The patients have to meet with a minimum of 12 points and no criteria should have a value of 0 in order to be discharged. If these conditions are not met, the surgeon could make a further assessment and decide whether the objective was achieved and, if it was not, proceed with the patient’s admission to the OS Ward. Together with discharge from the unit and review date, the patient would receive written instructions to follow at home which would differ depending on the procedure received.

Once the patient had been discharged, they would remain in close contact with the unit and with the OS service on 3 levels: by telephone contact 24h, by a telephone call the day after the operation made by the nurse from the unit and an outpatient consultation with the OS specialist one week after surgery.

This follow-up was reported in a computerized file at the unit, which was opened the day the patient presented for their operation. This file was filled in by the nurses, anaesthetists and surgeons, as the patient passed through the unit, and was closed on the 30th day after the operation following the review of their medical file. The database of the unit included a total of 39 variables for each patient. T he main study variables were generated from these variables, which have been called “clinical indicators”, in compliance with the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards11 and the International Association of MAS,1 which includes unplanned admissions: immediate or deferred.

The database was created with the statistical programme StatView 5.0.1, which was also used to carry out statistical analysis consisting in data synthesis and their presentation using descriptive statistics and hypothesis contrasting using the Chi square test, ANOVA test and Student’s t-test.

ResultsThe mean age of patients was 52.1 years (range 9–93), with the following distribution: 21.7 % were aged under 40, 58 % were between 41 and 65 and 20.3 % were over 66. 59.8 % were women. The patients who lived in the surrounding urban area of the hospital were 61.7 %, those less than one hour away were 35.1 %, those more than one hour away were 2.7 % and those in other provinces were .5 %. The ASA risk of patients was regarded as ASA I in 33.2 % of cases, ASA II in 56.2 % and ASA III stable in 10.6 %.

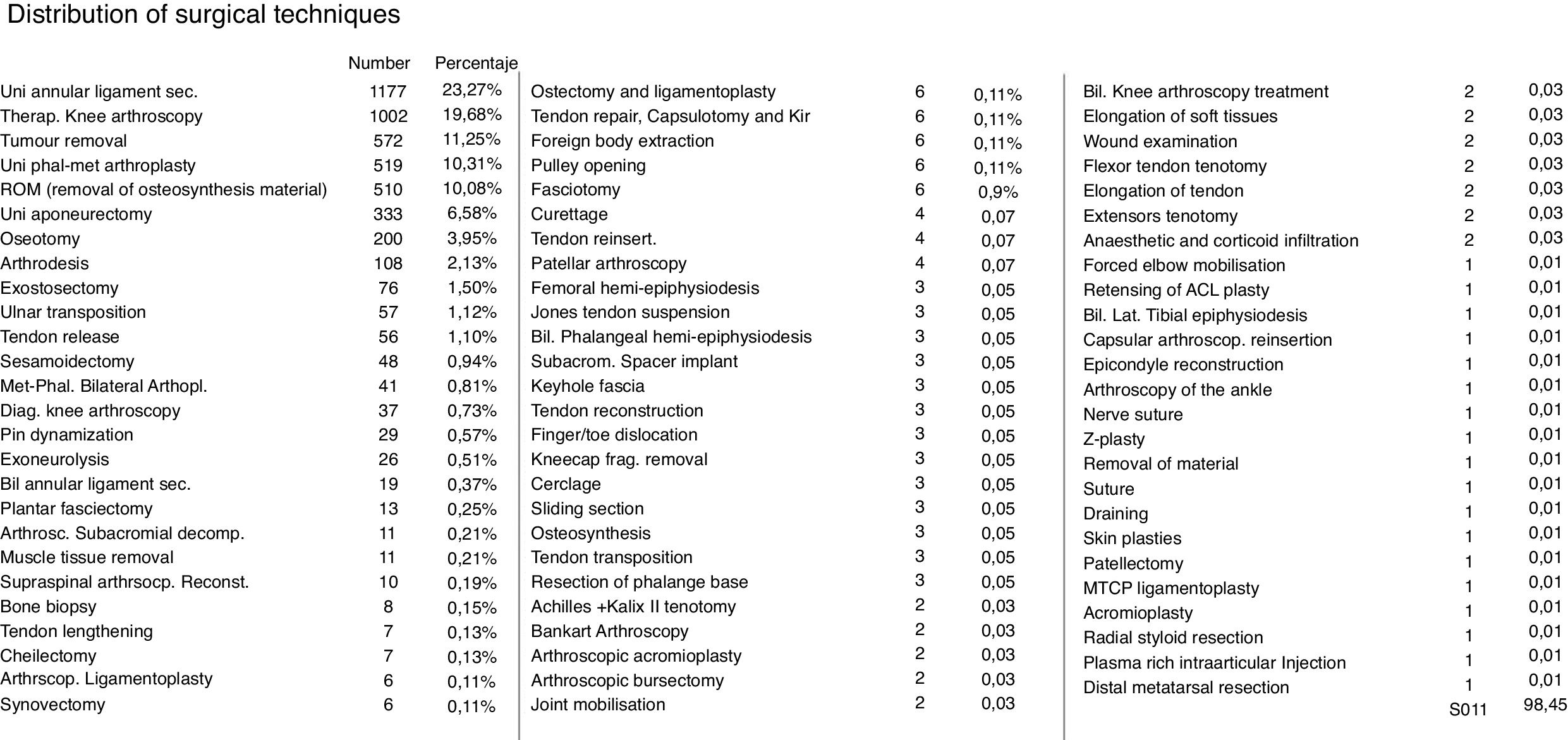

Patient diagnoses were classified into 4 groups. The first group, called Bone Pathology, with 31.9 % of patients essentially included those operated on for unilateral hallux valgus and removal of osteosynthesis material. The Arthroscopy group, with 21.6 %, included patients who had undergone arthroscopy of the knee of shoulder, with the former with cases of meniscus repair being the most frequent. The third group called Fascias/Tendons,with 34.3 %, included patients who had mainly been operated on for carpal tunnel syndrome and Dupuytren’s disease. Lastly, the Other Pathologies group, with 12.1 %, included other diagnoses, such as tumours and synovial cysts. Fig. 1 shows the list of surgical techniques used by order of frequency.

Seventy four patients, 1.5 % of the sample, were unable to be discharged and required hospitalisation. A total of 17 patients required readmission due to complications occurring in the home, 3 % of the sample. The remaining 1.4 % corresponded to patients who were unable to be operated on for different reasons, leading to suspension of the operation, and therefore of the patients who were finally operated on, 98.2 % were discharged.

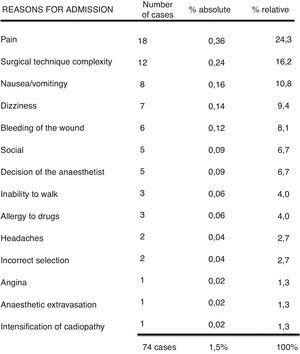

Of the 74 patients who after several postoperative hours of recovery in the recovery room, did not meet with discharge criteria, 18 presented with poor postoperative pain control. A total of 12 were admitted to hospital due to a more complex surgical technique than expected; 8 for postoperative nausea or vomiting; 7 for dizziness; 6 for bleeding from the surgical wound; 5 for social reasons (regardless of patient selection, the patients whose carers were reluctant to be discharged despite no complications arising); 5 due to anaesthesiological criteria; 3 because they were unable to walk and another 3 because they suffered from allergic reactions to the drugs (Fig. 2). The most frequent interventions where patients required immediate admission were in the Bone Pathology and Arthroscopy groups: hallux valgus corrections, knee arthroscopy, shoulder arthroscopy and removal of osteosynthesis material.

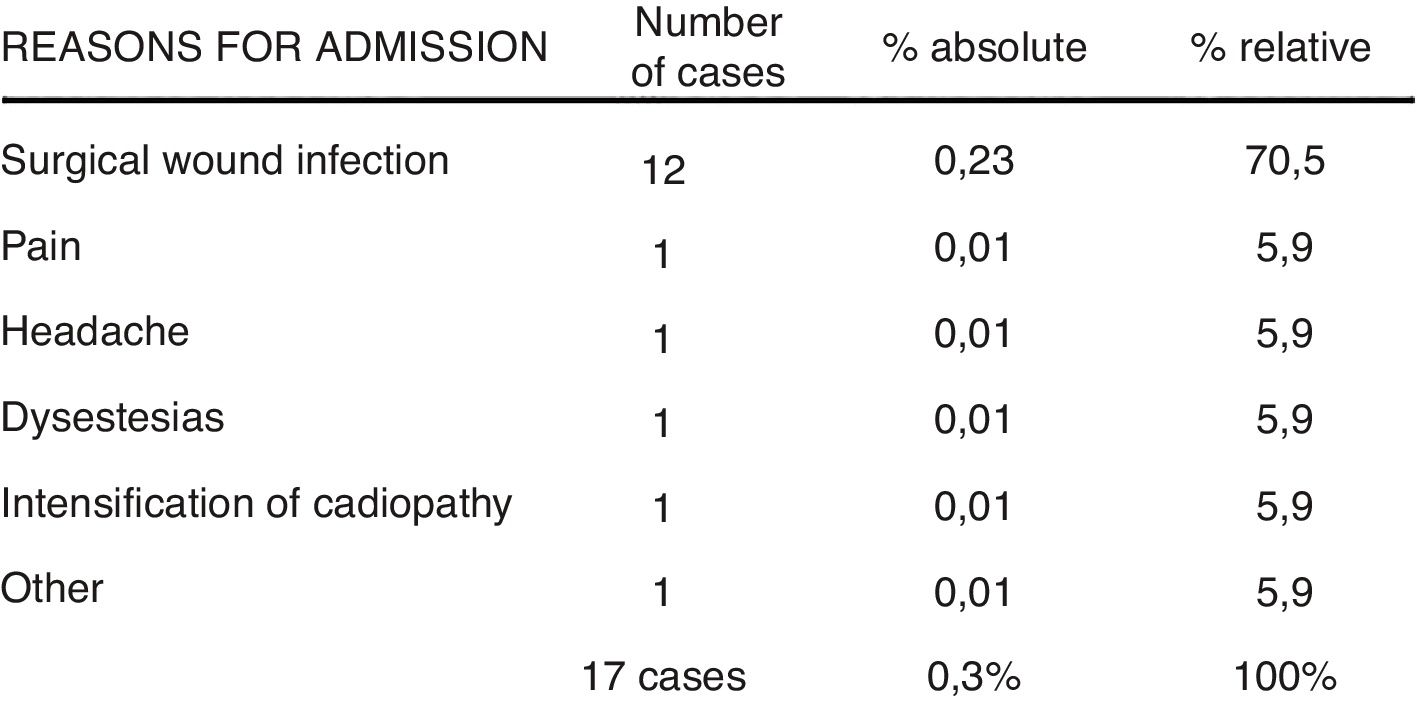

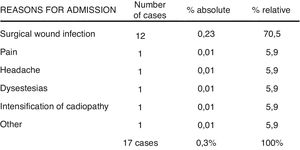

A total of 17 patients were discharged from the unit, but required deferred admission after a few hours or days at home. The most frequent cause was superficial infection of the surgical wound, which occurred in 12 cases: 7 hallux valgus, 2 tumours, one removal of osteosynthesis material, one knee arthroscopy and one Dupuytren’s disease and they only required intravenous antibiotic treatment. The other causes of deferred admission were only recorded in one patient per group and were for headaches, poor pain control, and intensified cardiopathy, among others (Fig. 3).

Spinal anaesthesia was used, in 38.3 % of cases, followed by regional intravenous at 21.3 %, local anaesthesia and sedation, 16.3 %, general anaesthesia, 14 %, and peripheral nerve block, 8.8 %.

The mean duration of interventions was 37.5min (range 1−180min).

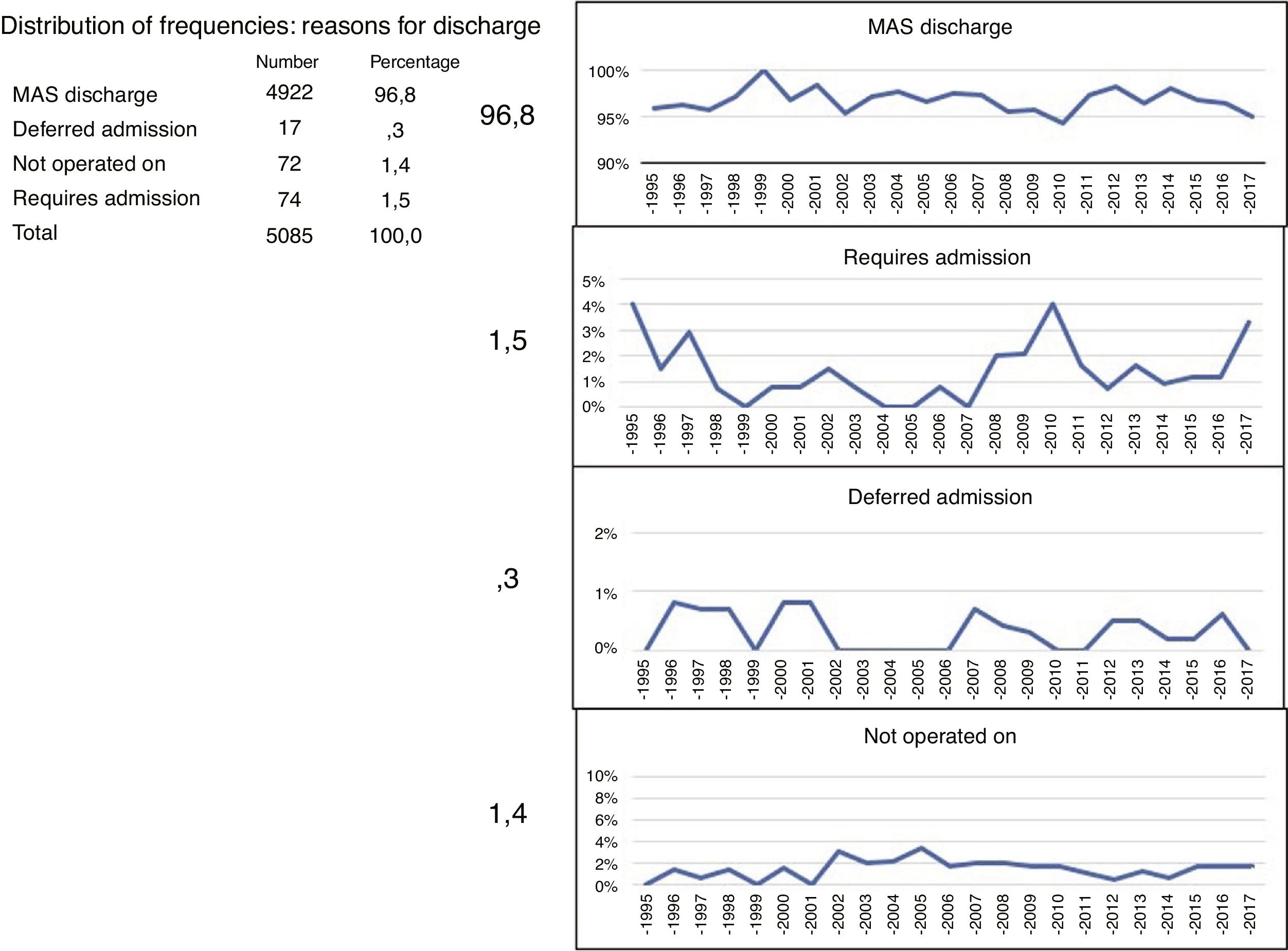

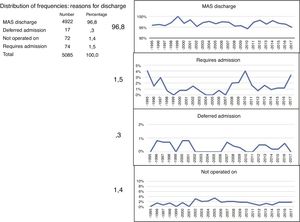

96.8 % of the total patients were discharged from the unit after meeting with the criteria, with a range between 94.3 % in 2010 and 100 % in 1999 (Fig. 4).

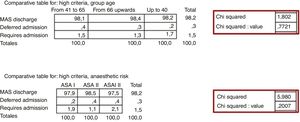

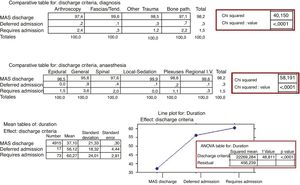

The 3 possible destinations of patients who were operated on after leaving the MAS unit were: home discharge, hospital admission or readmission after being discharged. There were no significant differences in percentage, when the patients were divided into 3 age groups or the ASA anaesthesia risk was taken into account, as shown in the Chi square test in the corresponding contingency tables (Fig. 5).

In contrast, when the 3 possible destinations on discharge from the unit were related with to the 4 diagnosis groups, significant differences were found, on observing that they required hospital admission, due to not meeting home discharge criteria, 2.4 % of the Arthroscopy group and 2.2 % of the Bone Pathology group, compared with 1.2 % of the Other Pathologies group and .3 % of the Fascias/Tendon group. The same occurred when comparing them with the type of anaesthesia practiced, on requiring 3.6 % of hospital admission in patients after a general anaesthesia, 2 % after spinal anaesthesia and the mean figures, 1.5 % or less, .3 % after intravenous regional anaesthesia and 0 % after local anaesthesia and sedation.

We found a significant difference between the mean 37min duration of patients discharged to their home and the 56min of those who required deferred admission or the 60min of those who required admission to hospital for not meeting discharge criteria (Fig. 6).

DiscussionThe results of the variables analysed in the study (diagnoses, age, ASA level, type of anaesthesia, etc.) are similar to those from the recent review by Martín-Ferrero et al.3 in a MAS unit of characteristics very similar to our own, although in our study the patients presented with a mean age of 10 years over, a higher number of ASA III patients and greater use of general anaesthesia and less of regional anaesthesia. Also, the percentage of home discharges, immediate and deferred admissions were similar to those reviewed in the literature.3–6

In MAS patient selection, experts like Kataria et al.12 and the British Association of Outpatient Surgery13 guide highlight that age and ASA level should not be limiting factors. Said data coincide with the unplanned percentage of admissions obtained in our series, showing no significant differences between age groups and anaesthetic risk, with these percentages being similar to those previously published within the context of the OS specialty in both similar units in Spain3 and the review conducted by American MAS centres.4

The duration of operations had a statistically significant impact on unplanned admission in our study, which coincides with reviewed literature. This indicates that when operations last longer than anticipated or terminate after 3 in the afternoon this is a predisposing factor for patients to require admission.3,4

However, unlike those reviewed in the literature, in our study diagnosis and type of anaesthesia was also statistically significant, which was not found to be the case in the reviewed studies.

Martín-Ferrero et al.’s3 experience is very similar to our own and reports that the most frequent causes to impede discharge or condition readmission during the first 24h after an operation are poor acute postoperative pain (APP) control, inflammation or bleeding from the wound and in contrast, between the second and 30th postoperative day, wound problems, particularly infections are the most frequent causes of hospital readmissions.

The development of a more complex surgical intervention than anticipated is a cause of admission which is difficult to avoid, but improving analgesic protocols, intensifying the battle against postoperative nausea and vomiting, making a better patient selection to avoid social admissions or for the anaesthetist to finally prefer to maintain admission would help to minimize unplanned patient admissions even further. Poor APP control is one of the most common causes of unplanned admissions reported in the literature.3,4,14 APP sometimes involves sensations of nausea and this often leads to dizziness and the impossibility of walking, added to which are factors stated by Arribas del Amo,15 which lead to unplanned admission.

Wound infection was the reason why most patients were readmitted. Recent reviews4,16 call into question the value of antibiotic prophylaxis and conceded higher importance to the presence of diseases such as diabetes, a smoking habit, obesity, alcohol abuse or a longer duration of the intervention. Recent publications corroborate that infection is the main cause of hospital readmission, finding age- associated comorbidities, high ASA status, type of intervention and even speciality17–20 as significant factors. Due to this prevalence of infection as a cause of unplanned readmissions, McCormack et al.17 highlight in their conclusions that their percentages could improve with better prevention of surgical site infection and by tightening the relationship between specialists and primary care. The importance of these factors are validated, supported by numerous significant data on the impact of advanced age, a high ASA level and associated comorbidities or a smoking habit by the NSQIP register of the American College of Surgeons, and other publications on hand and elbow surgery or knee arthroscopies,14,18–20 and finally the Mull et al.21 publication carried out with patients from centres with a high volume of day care surgery (which include general surgery, orthopaedic surgery, urology, otorhinolaryngology and podology).

There were no recorded cases of postoperative venous thromboembolic disease in our series, and therefore no admission took place due to this cause. This is in keeping with low or non incidence of data published by the CHEST22 guide or by the Mayo Clinic,23 all of which refer to knee arthroscopies. According to the literature, in hallux valgus, hallux rigidus or foot deformity surgery, which are highly common techniques in outpatient surgery, the rate of venous thromboembolic disease is also low, from .4 % to 1 %.24,25 Early mobilization and antithrombotic prophylaxis are the essential keystones to avert this complication.

This study has limitations of study period length, which covered a total of 22 years, during which major changes occurred regarding the spread of the MAS as an organisational system for OS procedures and also changes in surgical techniques. With regard to anaesthetic techniques, the eruption in recent years of peripheral blocks and their adaptation to APP control protocols to the recommendations of the Spanish Association of MAS (ASEMAS) could have led to some bias in the results.

ConclusionsBoth immediate and deferred unplanned admissions are more frequently related to the use of general anaesthesia, with operations of longer duration and procedures included in the Bone Pathology and Arthroscopy groups. We do not report that advanced age or a high ASA risk had any significant impact, although the ASA III patients recorded a higher number of admissions, which were not of statistical significance. With regard to the causes of the same, poor APP control in immediate admission and wound infections in deferred admissions were the most salient.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez Salas B, Ruiz Frontera M, Seral García B, García-Álvarez García F, Jiménez Bernadó A, Albareda Albareda J. Causas de ingresos no deseados tras la realización de procedimientos quirúrgicos de cirugía ortopédica y traumatología en cirugía mayor ambulatoria. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:50–56.