The bone cyst is a rare benign tumour that usually develops in childhood. There are several treatment options, however when it is located within the pelvis treatment is complex.

A 7 year-old patient who presented with 3 months of right hip pain and limping. The initial radiograph showed a discrete periostic reaction and acetabulum effacement. The MRI and CT scans suggested the diagnosis of aneurysmal bone cyst and was confirmed by open biopsy. Two serial embolizations were performed with good results, the patient was asymptomatic one year after.

El quiste óseo aneurismático es una lesión neoplásica poco frecuente, que se presenta generalmente en la infancia. Existen diversas alternativas de tratamiento, sin embargo cuando se localizan a nivel pélvico su tratamiento es complejo.

Paciente de 7 años que acude por coxalgia derecha y cojera de 3 meses evolución. En la radiografía inicial se observa discreta reacción periódica y borramiento del trasfondo acetabular. Se realiza resonancia magnética y tomografía, que sugieren el diagnóstico de quiste óseo aneurismático confirmándose mediante biopsia a cielo abierto. Se realizan dos embolizaciones seriadas con buena evolución, mostrándose el paciente asintomático al año.

Aneurysmal bone cyst is a true neoplasm characterised by a t (16;17) chromosomal translocation. In primary cases it is suggested that this tumour is characterised by a mutation in the said chromosome, and that it is both expansile and locally destructive.1 It has a very low probability of metastasis, although it has a high rate of local recurrence. This lesion is composed of different-sized blood-filled spaces which are separated by walls of vascular connective tissue.1,2 It represents 1% of all primary benign bone tumours; 3% occur in the sacrum and 8–12% occur at the level of the pelvis.1,3 Aneurismal bone cyst aetiology is still controversial. They may be primary bone lesions (70% of cases) or secondary lesions to other bone pathologies (30% of cases).

These cysts rarely regress spontaneously.2,3 They are usually treated successfully by intralesional curettage and bone graft when they are located in the limbs, although other therapeutic possibilities include embolisation prior to curettage and filling with spongy material and percutaneous sclerotherapy.

However, special factors must be taken into account when treating aneurismal bone cysts at the level of the pelvis. These include the relative inaccessibility of the lesion, associated intraoperative bleeding, the proximity of neurovascular structures, acetubular and sacroiliac joint vulnerability.

We present the clinical case of a 7 year-old boy who was diagnosed with acetubular aneurismal bone cyst and treated using selective serialised embolisation.

Clinical caseThis case is of a 7 year-old boy with no relevant medical antecedents who consulted due to symptoms of right coxalgia spreading to the right leg with inflammatory characteristics that had evolved over approximately three months. It had gradually increased in intensity and required the habitual use of non-steroid anti-inflammatory medication, and it was associated with claudication when walking.

Physical examination showed the patient to be in good general health, normally coloured and hydrated, with no cutaneous or palpable adenopathies. He clearly limped when walking, with localised pain in the right groin and restricted mobility of the right hip, with 100° flexion, 0° internal rotation and 30° external rotation. Vascular and nerve involvement were ruled out.

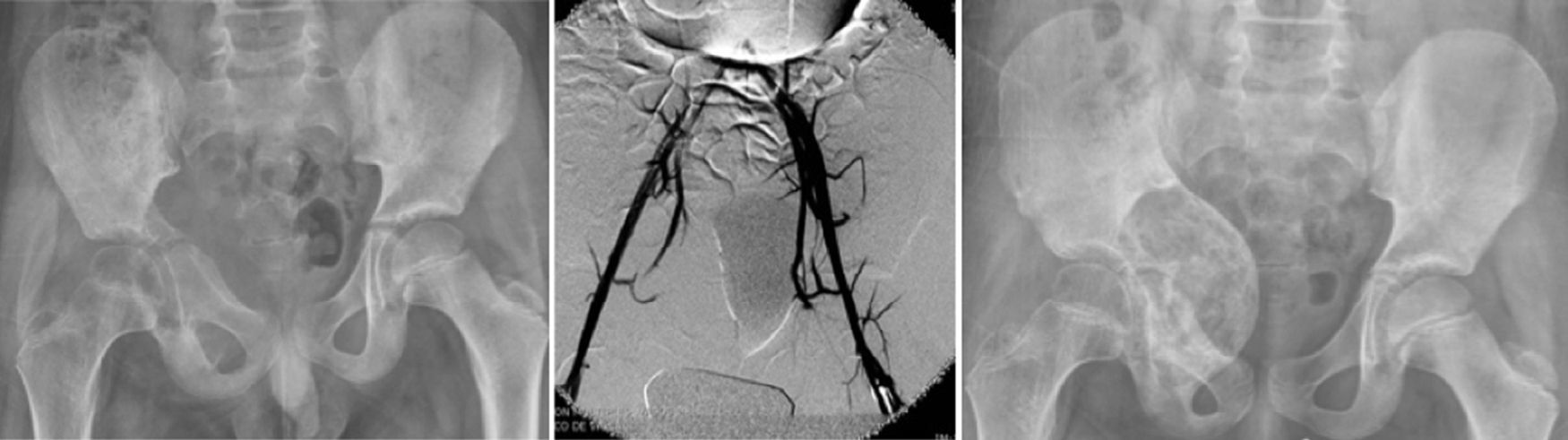

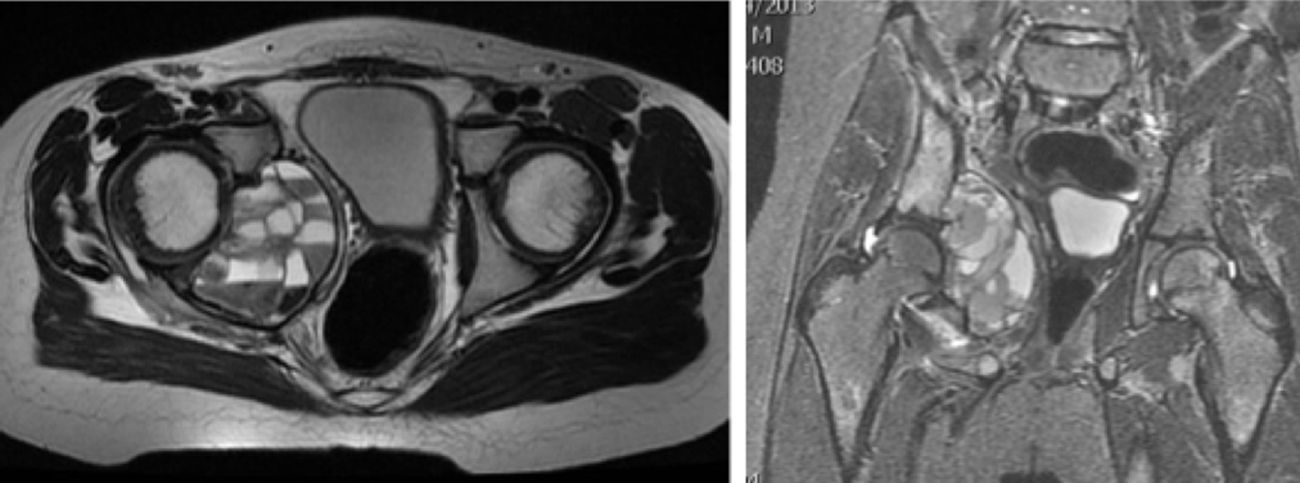

Imaging tests were performed using simple X-ray of the pelvis, showing an image of periosteal reaction and discreet fading of the right acetabular background (Fig. 1); abdominal ultrasound ruled out visceral lesions, involvement of the urinary system or free intraperitoneal liquid, although extrinsic compression of the right wall of the bladder was observed, caused by a mass of multiple cysts; NMR of the pelvis showed a bone tumour on the inner side of the right acetabulum, 72mm×52mm×38mm in size, of insufflated appearance, with multiple cystic cavities containing levels of liquid – liquid with subacute haematic residues, without soft tissue involvement and gadolinium capture at the level of the septa and lesion periphery, compatible with an aneurismal bone cyst (Fig. 2); CT of the pelvis showed an expansile lytic lesion in the acetabular background and right ischium, with cortical narrowing and hypointense areas within it. Laboratory tests showed iron-deficiency anaemia.

The first diagnostic option with these clinical findings was aneurismal bone cyst of the right acetabulum. To confirm this diagnosis and to undertake differential diagnosis with other tumour types such as telangiectatic osteosarcoma or giant cell tumour, a CT scan-guided needle biopsy was taken. This ruled out the presence of malign neoplastic cells.

Given the high risk of bleeding that would be hard to control due to the location and large size of the lesion, which prevented traditional treatment using curettage/block exeresis and filling with bone graft, it was decided to carry out percutaneous embolisation of the tumour.

5 days after the embolisation the patient had intense pain which partially improved with analgesics. New X-ray and NMR imaging tests showed that the volume of the lesion had increased by 1cm.

Given these findings it was decided to perform an open biopsy using an iliac-groin approach. For this an incision was made along the iliac crest, over the anterosuperior iliac spine and towards the side of the thigh. The sartorius and fasciae latae tensor muscles were then divided, with subperiosteal disinsertion of the abdominal and iliac muscles by periosteotomy. Both origins of the straight muscle were divided, with medial incision and retraction of the periosteum from the surface of the anterior wall of the acetabulum, thereby accessing the floor and anterior wall and therefore the lesion.

Pathological study confirmed the diagnosis of aneurismal bone cyst. Two weeks later percutaneous embolisation of the lesion was repeated (Fig. 1).

After this second embolisation the patient evolved satisfactorily, with gradual reduction of the pain until it disappeared completely. Claudication while walking also ceased, with gradual improvement in right hip mobility until a complete range of movement was achieved.

Imaging tests showed steady filling of the cystic lesion (Fig. 1). At the present time and after one year the patient is living normally and is completely asymptomatic, while the follow-up X-ray shows complete ossification of the cyst (Fig. 1).

DiscussionAneurismal bone cyst represents 1% of bone tumours, with an incidence of 0.14 per 100,000 inhabitants. It typically appears during childhood, and 76% of cases are in patients under the age of 20 years old, while 90% are in those under the age of 30 years old. Approximately 12% of cases present in the pelvis.4,5

Diagnosis may be by simple X-ray of the pelvis, although lytic zones are often not recognised at the start of the disease. Although bone scintigraphy with technetium is a sensitive method for detecting pelvic lesions, aneurismal bone cysts are visualised better using computerised axial tomography or magnetic resonance.5 Lesion definition, its size and identification of its type are shown better using diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance images than is the case with tomography.6 MRI shows the multiple levels of liquid within a multilocular lesion, which is best visualised in T2 amplified magnetic resonance images. The first examination in our case was by X-ray, showing a blurred acetabular background and a branched periosteal reaction. Subsequent ultrasound examination in the emergency department showed a multicystic lesion, while MRI subsequently gave us all of the information required for diagnosis of a presumable aneurismal bone cyst.

Aneurismal bone cyst treatment in the pelvis and sacrum must be individualised depending on the location, size and aggressiveness of the lesion.

Treatment is complex due to the relative inaccessibility of these lesions, associated intraoperative bleeding, their closeness to neurovascular structures and the vulnerability of the acetabulum or sacroiliac joint. Treatment options include complete resection, curettage, curettage combined with bone graft, selective arterial embolisation as the primary definitive treatment or preoperative adjuvant therapy, and percutaneous injection of a fibrosing agent.1–3

Current curettage technique involves going beyond the reactive zone surrounding the lesion. Lesions ≤5cm which present minimum cortical destruction or expansion and which do not threaten the integrity of the acetabulum or sacroiliac joint are best treated by intralesional curettage, with or without a bone graft. Lesions >5cm that show large areas of cortical bone destruction or expansion and which threaten the integrity of the acetabulum or sacroiliac joint require a more aggressive approach using division-curettage.2

The percutaneous injection of a fibrosing agent (Ethibloc, Ethicon) has been used recently with promising results.7

Selective embolisation may also be used as a primary treatment for aneurismal bone cysts in anatomical locations where surgery would be complex, as well as an adjuvant treatment to surgery to reduce intraoperative blood loss and to aid curettage.8 The chief advantage of selective arterial embolisation is that it avoids surgery and thereby also avoids complications such as hip instability, skeletal deformations, infections, neurovascular lesions and prolonged rehabilitation, together with the need for subsequent complex reconstructive surgery.9,10

The success rate for aneurismal bone cyst embolisation stands at from 75% to 94%.11,12 The rate of recurrence after aneurismal bone cyst embolisation varies from 39% to 44%.12 In our case, at the moment of diagnosis the patient presented a lesion >5cm, so that due to the difficultly of accessing it surgically and its size it was decided to treat it using embolisation. Embolisation is currently considered to be an alternative treatment for aneurismal bone cysts when access to them is difficult.13,14 The persistence or recurrence of these lesions after embolisation has been associated with cysts larger than 5cm.12 When lesions are persistent or recurring embolisation may be repeated to achieve a cure.12 After the first embolisation our patient continued with symptoms of pain and even a slight increase in the size of the lesion, which was then successfully treated by a second embolisation.

Nevertheless, embolisation is not free of complications. The general risk of these associated with this technique stands at 6%, and they consist of dissection of the femoral artery at the site of catheterisation, pain due to ischaemic necrosis of the tumour, accidental embolisation of non-tumour vessels, infection and post-embolisation syndrome.

Repeated selective embolisation is therefore a good therapeutic alternative for large pelvic cysts. It has few complications in comparison with the other therapeutic alternatives.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. This document is in the hands of the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Dr. Palmero, Head of the Radiology Department, and Dr. Silvestre for his help in this case.

Please cite this article as: Saus Milán N, Pino Almero L, Mínguez Rey MF. Quiste óseo aneurismático localizado en trasfondo acetabular en un niño de 7 años: a propósito de un caso. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:256–259.