Antibiotic prophylaxis is the most suitable tool for preventing surgical wound infection. This study evaluated adequacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery for knee arthroplasty and its effect on surgical site infection.

Material and methodProspective cohort study. We assessed the degree of adequacy of antibiotic prophylaxis, the causes of non-adequacy, and the effect of non-adequacy on surgical site infection. Incidence of surgical site infection was studied after a maximum incubation period of a year. To assess the effect of prophylaxis non-adequacy on surgical site infection we used the relative risk adjusted with the aid of a logistic regression model.

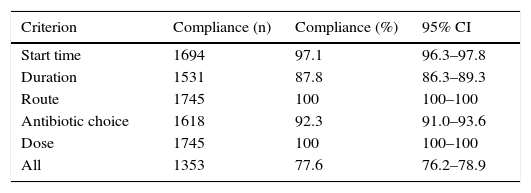

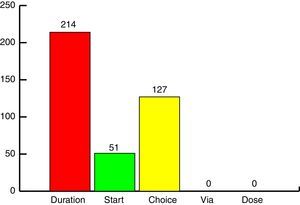

ResultsThe study covered a total of 1749 patients. Antibiotic prophylaxis was indicated in all patients and administered in 99.8% of cases, with an overall protocol adequacy of 77.6%. The principal cause of non-compliance was the duration of prescription of the antibiotics (46.5%). Cumulative incidence of surgical site infection was 1.43%. No relationship was found between prophylaxis adequacy and surgical infection (RR=1.15; 95% CI: 0.31–2.99) (P>0.05).

DiscussionSurveillance and infection control programmes enable risk factors of infection and improvement measures to be assessed. Monitoring infection rates enables us to reduce their incidence.

ConclusionsAdequacy of antibiotic prophylaxis was high but could be improved. We did not find a relationship between prophylaxis adequacy and surgical site infection rate.

Evaluar el grado de adecuación al protocolo de profilaxis antibiótica en pacientes intervenidos de artroplastia de rodilla y su influencia en la infección quirúrgica.

Material y métodoSe realizó un estudio de cohortes prospectivo. El grado de adecuación se estudió mediante la comparación de las características de la profilaxis recibida por los pacientes y la estipulada en el protocolo vigente de nuestro hospital. El efecto de la profilaxis en la incidencia de la infección quirúrgica se estimó con el riesgo relativo.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 1.749 intervenciones. La incidencia de infección del sitio quirúrgico fue del 1,43% (n=25). La adecuación global al protocolo de profilaxis antibiótica fue del 77,6%. La causa más frecuente de inadecuación al protocolo fue la duración prescrita de los antibióticos de la profilaxis (46,5%). La adecuación de la profilaxis antibiótica no influyó en la infección del sitio quirúrgico (RR = 1,15; IC 95%: 0,31–2,99; p > 0,05).

DiscusiónLos programas de vigilancia y control de la infección permiten evaluar factores de riesgo de infección y evaluar medidas de mejora. La vigilancia de las tasas de infección quirúrgica nos permite tomar las medidas oportunas encaminadas a reducir progresivamente su incidencia.

ConclusionesLa adecuación de la profilaxis antibiótica fue alta, pero se puede mejorar. No hubo relación entre la adecuación de la profilaxis y la incidencia de infección de la herida quirúrgica en artroplastia de rodilla.

Approximately 5% of patients admitted to hospital pick up an in-hospital infection.1 Surgical site infection (SSI) is in third place among in-hospital infection, with it being the most common infection in surgical patients,2 associated with a mortality rate of 3%.3,4

The Spanish national network for oversight of infection incidence, Clinical Indicators of Infection and Continual Quality Improvement, estimates that the accumulated incidence of overall infection in trauma and orthopaedic surgery to be some 1–5%.5

The presence of SSI increases patient risk and severity,6,7 and its incidence depends on the degree of contamination from the surgical technique and on intrinsic and extrinsic patient risk factors. SSI means an increase in mean hospital stay, a rise in healthcare costs and a decrease in the patient's quality of life.8,9

A strategy that has proven effective in preventing and controlling infection of the surgical site is the use of antibiotic prophylaxis.10 The main goal of antibiotic prophylaxis is to reach a high serum drug level during the surgical process and in the hours immediately after closing of the incision. If the antibiotic used is sufficiently active against the potentially contaminating microorganisms and maintains elevated concentration levels during the entire surgical procedure, the prophylaxis, in general, will be effective.11

Our hospital has a protocol for administration of antibiotic prophylaxis in agreement with the guidelines reviewed in the literature and it is updated constantly by the infection commission in the centre. The objectives of our study were to assess compliance with this antibiotic prophylaxis protocol in patients having knee arthroplasty, and to assess its efficacy in preventing infection of the surgical site.

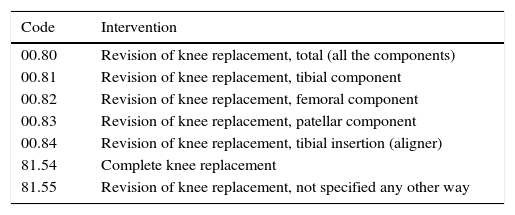

Material and methodThis was a prospective cohort study for assessing the adequacy of antibiotic prophylaxis to the protocol in knee arthroplasty surgery. Assessment was carried out in the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (University Teaching Hospital Alcorcón Foundation), in Madrid, and was performed by the preventative medicine and trauma and orthopaedic surgery services. Patients with knee surgery replacements and revisions without infection at the time of the intervention were included. Table 1 presents the detailed list of surgical procedures included, together with the corresponding codes from the “International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification” according to Centers for Disease Control (CDC) criteria for knee arthroplasty. Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered in the waiting period for beds before surgery by nursing personnel under supervision of the anaesthetists. The prophylaxis was recorded on the anaesthesia sheet.

Surgical procedures studied (ICD-9-CM) for knee arthroplasty.

| Code | Intervention |

|---|---|

| 00.80 | Revision of knee replacement, total (all the components) |

| 00.81 | Revision of knee replacement, tibial component |

| 00.82 | Revision of knee replacement, femoral component |

| 00.83 | Revision of knee replacement, patellar component |

| 00.84 | Revision of knee replacement, tibial insertion (aligner) |

| 81.54 | Complete knee replacement |

| 81.55 | Revision of knee replacement, not specified any other way |

ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Sample size was calculated on the basis of a 95% confidence interval (CI); power of 95%; an incidence of infection of 1% in the group with adequate prophylaxis and 5% in the group with inadequate prophylaxis; an adequacy/inadequacy ration of 4% and estimated losses during follow-up of 1%. Consequently, a theoretical sample of 1626 patients was estimated, who were included consecutively.

The criteria for exclusion were as follows: confirmation or suspicion of infection on the date of the intervention, or having been under antibiotic treatment before it. The study included the patients who received knee arthroplasty in the Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery Service between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2015. The study was approved by the ethics committee and the research commission of the hospital.

Study variables were patient age and sex, as well as varied aspects of the antibiotic prophylaxis, including antibiotic chosen, administration route and time, and treatment length and dose. Compliance with the preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis (appropriate or inappropriate) and the presence or lack of SSI. All patients were followed clinically for a year based on the progression of the surgical wound, clinical profile and microbiological results, according to the CDC definitions.12 If an SSI was detected, its depth (superficial incisional, deep incisional or organ-space) and the infection-producing microorganism. The microbiological studies to identify the microorganisms involved were carried out using a MicroScan Walkaway unit (Siemens®).

A specific sheet for data collection, and a normalised, relational database were designed using the Microsoft Access® programme for their register. A descriptive sample study was performed. Qualitative variables were described with their frequency distributions (number and percentage) and were compared using the binomial test. Quantitative variables were described with their mean and standard deviation (SD). The criterion for normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test and the 2-category quantitative variables were compared using the Student t-test or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test.

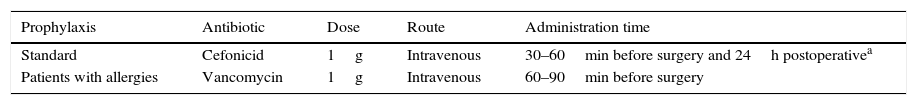

The degree of compliance was studied by comparing the antibiotic prophylaxis received by the patients and the prophylaxis established in the protocol in force in our hospital, which is shown in Table 2. During the study, compliance was assessed for all the aspects defined in the protocol, both taken together and individually. The incidence of SSI was assessed after the follow-up period; how prophylaxis compliance affected the infection incidence was estimated using relative risk (RR) adjusted with a logistic regression model. All the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS v20 statistical programme.

Protocol for antibiotic prophylaxis in knee arthroplasty.

| Prophylaxis | Antibiotic | Dose | Route | Administration time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Cefonicid | 1g | Intravenous | 30–60min before surgery and 24h postoperativea |

| Patients with allergies | Vancomycin | 1g | Intravenous | 60–90min before surgery |

A total of 1749 patients were included in the study: 1272 women (73%) and 477 men (27%). Mean age was 70 years for the general study population (SD=22.2), 71 years (SD=12.4) for the women and 69 years for the men (SD=14.1) (P<0.05). Mean operation length was 119.9min (SD=43.4). Mean length of hospital stay for non-infected patients was 8.1 days (SD=10.6) and 28.7 days (SD=9) for patients with surgical site infection.

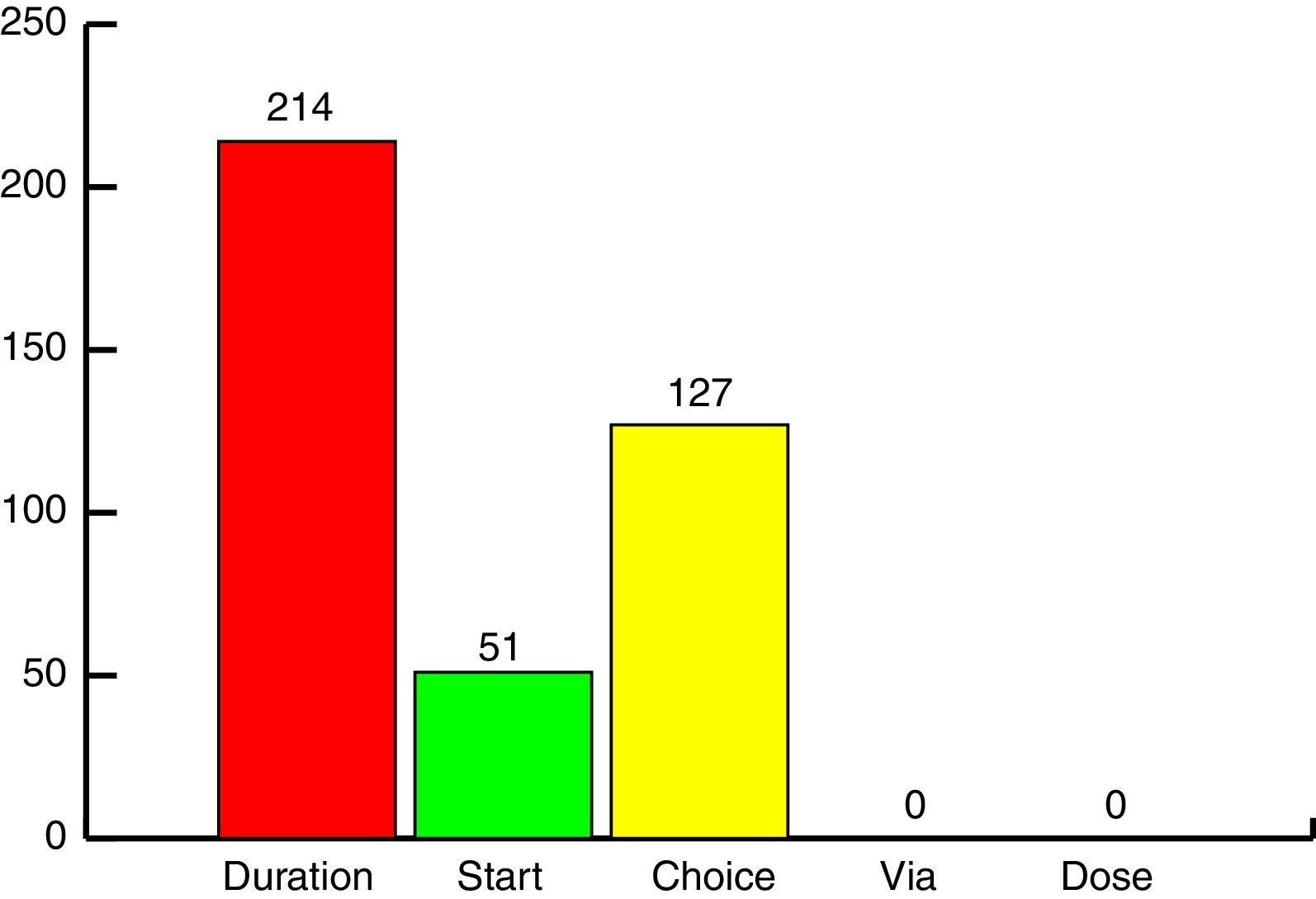

Administration of antibiotic prophylaxis was indicated in all patients studied. The prophylaxis was given to 1745 patients, with a 99.8% degree of protocol compliance. Prophylaxis administration could not be documented in 4 patients (0.2%). Protocol compliance, taking all the criteria into consideration, was 77.6%. Table 3 presents the percentages and total number of patients who complied with the protocol in each criterion studied. The most frequent cause of lack of compliance was the length of antibiotic prophylaxis (46.5%), followed by antibiotic choice (Fig. 1).

Adequacy of the antibiotic prophylaxis protocol (n=1745).

| Criterion | Compliance (n) | Compliance (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Start time | 1694 | 97.1 | 96.3–97.8 |

| Duration | 1531 | 87.8 | 86.3–89.3 |

| Route | 1745 | 100 | 100–100 |

| Antibiotic choice | 1618 | 92.3 | 91.0–93.6 |

| Dose | 1745 | 100 | 100–100 |

| All | 1353 | 77.6 | 76.2–78.9 |

CI: confidence interval.

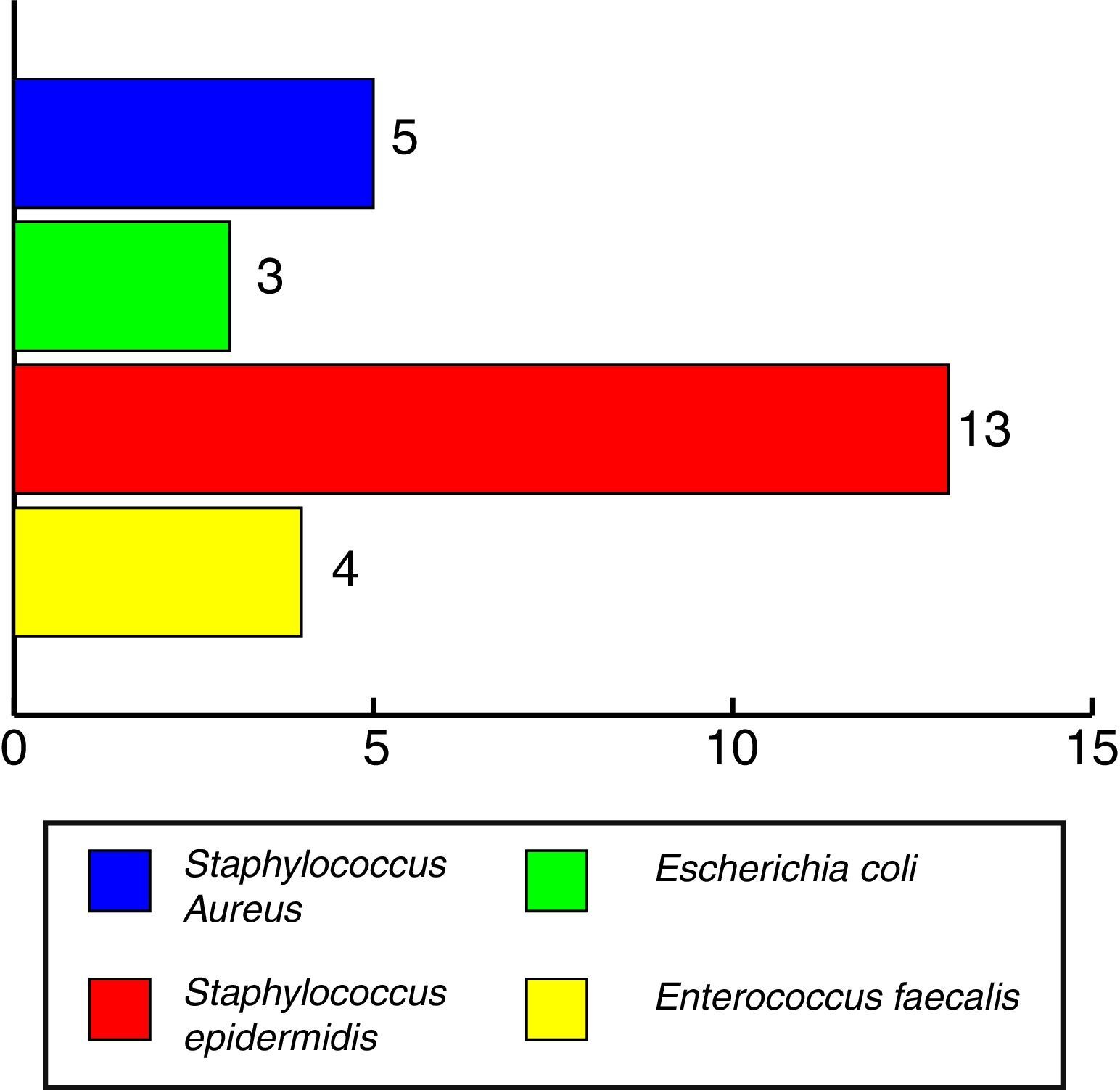

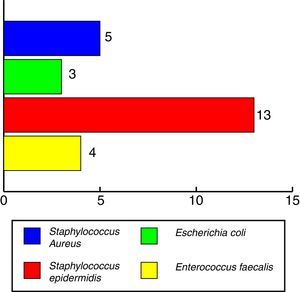

The overall SSI incidence at the end of follow-up was 1.43%. Broken down by the different types of infection, the incidence was as follows: 0.3% for superficial incisional infection of the wound; 0.7% for deep incisional infection, and 0.4% for organ-space infection. The most commonly involved microorganism in surgical infection was Staphylococcus epidermidis (52% of infected patients), while 19% of the patients having SSI were infected by more than 1 microorganism. The microorganisms that produced the infection can be seen in Fig. 2.

The relationship between the incidence of infection and overall inadequacy of the antibiotic prophylaxis was RRcrude: 1.23; 95% CI: 0.41–3.67. This relationship was also kept when RR was adjusted for the different covariables (RRadjusted: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.31–2.99) (P>0.05). The individual effect of each aspect of the prophylaxis in which there was inadequacy was evaluated: choice RRcrude: 1.81; 95% CI: 0.48–14.3; length RRcrude: 1.72; 95% CI: 0.65–5.4 and start RRcrude: 0.14; 95% CI: 0.01–1.14.

DiscussionThis study assessed the administration of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients receiving knee arthroplasty and the degree of compliance with the protocol in our centre. Compliance with this protocol was 99.8%; we were unable to find such a high figure in the references consulted.13 The percentage of overall adequacy of the prophylaxis was 77.6% among the patients who received antibiotic prophylaxis, when the factors were evaluated as a whole. This percentage is slightly less than the degrees of general compliance described in the literature.14,15

Individualising each criterion of the protocol (start of prophylaxis, length, administration route, and antibiotic choice and dose), the degree of compliance is above 90% for each of them, except for the length of antibiotic prophylaxis treatment. These figures fall in a range equal to or greater than those found in the bibliography.16

The factor that contributed the most to lack of protocol compliance was the length of inappropriate antibiotic prophylaxis, because the antibiotic was administered for longer than recommended. It is currently known that the dosage of antibiotic used should be that in which values above the minimum inhibitory concentration during a time period longer than that of the intervention. The dose should be repeated if the surgical intervention lasts longer than double the mean life of the antibiotic, or if there is a blood loss greater than 1.5l after fluid administration.17

The patients were given the antibiotic prophylaxis by nursing staff in the surgery waiting room, as indicated in our hospital protocol, with the staff being supervised by the anaesthetists in charge of its administration and the antibiotic data being registered on the anaesthesia sheet. Given that neither the nursing staff nor the anaesthetists knew that they were going to be assessed, it was possible to control the Hawthorne effect in our study.

The incidence of infection in our series was slightly above that published by the CDC12 and other studies18,19 for this procedure, while being similar a those in our sphere of influence.5,14,20 The control of SSI determines the level of quality of the medical care, in that it is essential for the safety of the patient operated on.21 Every surgical intervention involves an increase in the risk of the patient suffering an infection, which can either appear in the surgical wound or transfer to more distal areas. According to the studies on the incidence of infection of the surgical site, deep incisional and organ-space infections cause 2/3 of all SSI,22 and antibiotic prophylaxis is a means of proven efficacy for lowering the SSI rate significantly, with the consequent reduction in hospital stay, healthcare cost, and patient mortality and morbidity.23–26

The follow-up period constitutes a key point in our study, as cases 1 year after the surgery were also assessed. This should be taken into consideration when analysing the incidence reached.27 Even so, the main study objective was to assess the adequacy of the prophylaxis, so the study results are not affected by this fact.

As for the microbiological analysis, the most commonly involved microorganisms in SSI were S. epidermidis (52%) and Staphylococcus aureus (20%). These results are comparable to those found in other similar studies.28,29

As a result of our assessment, various measures were taken in our centre. Examples are as follows: communicating the results to the physicians in charge of the patient and having the entire healthcare team focus on the protocol, reminding them to try to improve adherence to its recommendations. Various publications have shown that monitoring surgical procedures, based on the surgeons knowing the results (feedback) can significantly reduce infection rates.30

With respect to the limitations of our study, one is the possible losses during follow-up after discharge. Losses were estimated in calculating the sample size to be able to control them. Our centre has electronic case histories and the patients are followed using the Horus® computer application after discharge. Consequently, it was possible to control the biases of selection and information.

In conclusion, emphasis should be given to the importance of applying and continually evaluating the protocols for antibiotic prophylaxis in orthopaedic surgery and trauma, so that the appropriate measures can be taken to reduce the incidence of SSI. Both compliance to and adequacy of prophylaxis is high in our study, but there is always room for improvement. Along these lines, implementing evidence-based recommendations, which are simple are viable, together with active participation of all professionals involved, are essential for improving the safety of the surgical patient.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed comply with the ethics standards of the appropriate Human Experimentation Committee and are in agreement with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre about the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects indicated in this article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FundingThis study has been funded by the research projects PI11/01272 and PI14/01136, granted by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) (Healthcare Research Foundation) and the Fondo Europeo para el Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) (European Foundation for Regional Development).

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The researchers wish to thank the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) for funding this study through Research Projects PI11/01272 and PI14/01136.

Please cite this article as: del-Moral-Luque JA, Checa-García A, López-Hualda Á, Villar-del-Campo MC, Martínez-Martín J, Moreno-Coronas FJ, et al. Adecuación de la profilaxis antibiótica en la artroplastia de rodilla e infección del sitio quirúrgico: estudio de cohortes prospectivo. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:259–264.