The incidence of periprosthetic fractures of the knee is increasing due to the increase in the number of total knee arthroplasties performed, together with population aging. We found few studies that analyze mortality in our setting after surgery. Our objective was to evaluate mortality and survival after surgical treatment of periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur in our environment.

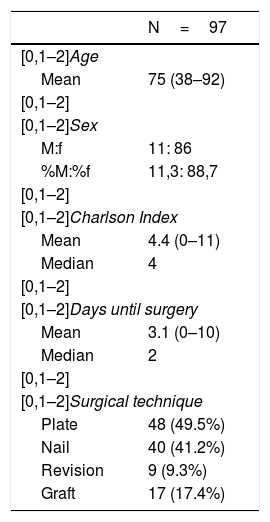

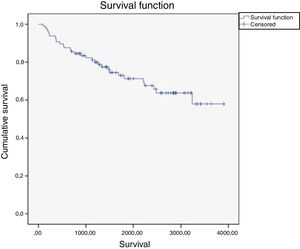

Material and methodWe conducted a retrospective observational study of a consecutive series of 97 patients surgically treated in our centre for periprosthetic knee fracture between 2007 and 2015, with a minimum follow-up of 12 months. Diverse sociodemographic, clinical and surgical variables were analyzed. A consultation was made to the National Death Index of the Ministry of Health for the analysis of mortality and survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

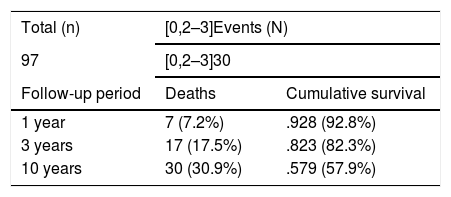

ResultsWe reviewed a total of 97 patients with an average age of 75 years, of which 86 were women and 11 were men. Of the patients, 50.5% of patients had some comorbidity. The average delay until the intervention was 3.1 days. With respect to the treatment, 45 patients were operated by osteosynthesis with plate (49.5%), 40 with intramedullary nail (41.2%) and 9 with revision of the arthroplasty (9.3%). A total of 30 deaths were recorded during the follow-up, with cumulative mortality in the first year, at 3 and at 10 years of 7.2%, 17.5% and 30.9%, respectively, progressively increasing in people over 75 years. There was no significant difference in mortality rates with the osteosynthesis method. The main complication was pseudoarthrosis (6.2%).

ConclusionsPeriprosthetic knee fractures are associated with high rates of complications and mortality. The patient's age and the lesion itself are non-modifiable factors that can influence mortality after surgery, while other variables such as the type of intervention or surgical delay did not show differences in mortality rates in our study.

Está aumentando la incidencia de las fracturas periprotésicas de rodilla debido al incremento en el número de artroplastias totales de rodilla realizadas, junto al envejecimiento poblacional. Encontramos escasos estudios que analicen en nuestro medio la mortalidad a largo plazo tras la intervención quirúrgica. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la mortalidad y supervivencia tras el tratamiento quirúrgico de las fracturas periprotésicas de fémur distal en nuestro medio.

Material y métodosRealizamos un estudio observacional retrospectivo de una serie consecutiva de 97 pacientes intervenidos quirúrgicamente en nuestro centro por fractura periprotésica de rodilla entre los años 2007-2015, con un seguimiento mínimo de 12 meses. Se analizaron estadísticamente diversas variables sociodemográficas, clínicas y quirúrgicas. Se realizó una consulta al Índice Nacional de defunciones del Ministerio de Sanidad para el análisis de mortalidad y se analizó la supervivencia utilizando el método Kaplan-Meier.

ResultadosRevisamos un total de 97 pacientes con edad media de 75 años, de los cuales 86 fueron mujeres y 11 fueron hombres. El 50,5% de los pacientes presentaba alguna comorbilidad. La demora media hasta la intervención fue de 3,1 días. Respecto al tratamiento, 45 pacientes fueron intervenidos mediante osteosíntesis con placa (49,5%), 40 de ellos con clavo intramedular (41,2%) y en 9 se realizó una revisión de la artroplastia (9,3%). Se registraron un total de 30 defunciones durante el seguimiento, con una mortalidad acumulada al año, a los 3 años y a los 10 años del 7,2%, 17,5% y 30,9%, respectivamente, aumentando progresivamente en mayores de 75 años. No hubo diferencias significativas en las tasas de mortalidad respecto al método de osteosíntesis. La principal complicación fue la pseudoartrosis (6,2%).

ConclusionesLas fracturas periprotésicas de rodilla se asocian a altas tasas de complicaciones y de mortalidad, siendo la edad del paciente y la propia lesión factores no modificables que pueden influir en la mortalidad tras la cirugía, mientras que otras variables como el tipo de intervención o la demora quirúrgica no mostraron diferencias en las tasas de mortalidad en nuestro estudio.

In primary knee arthroplasties, the incidence of fracture has been described as ranging from .3% to 2.5%,1–3 with a higher incidence in revision arthroplasties of between 1.6% and 38.0%.2 Due to the increased life expectancy of patients and the increased use of primary knee arthroplasties, a higher prevalence of these injuries is to be expected. These fractures are usually the result of a low-energy mechanism, such as a fall on the knee,3 with the main location being the distal femur.

Despite the extensive literature on periprosthetic fractures, most publications have focused on functional and radiological outcomes comparing the different treatment methods,4,5 but limited information is available on long-term mortality. Periprosthetic femoral fractures are associated with high mortality rates, especially during the first postoperative year.1,2,6–8 The mortality risk of these fractures is significantly higher than that of primary knee arthroplasties or osteosynthesis of distal femoral fractures.9 The advanced age of the patient and their medical comorbidities will increase the risk of mortality, especially in the long term, while the injury itself, as well as its surgical treatment, will be especially relevant during the short-term postoperative period.6,10–12

Studies on the mortality of this type of injury generally report mortality rates after a certain period of follow-up, a variable that is inconsistent between the studies, making it difficult to group data and compare with other papers. This study aims to determine the mortality rate associated with periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur after different follow-up periods, to determine the probability of patient survival and to assess the surgical variables that are associated with mortality. As secondary objectives, we compared the associated mortality for each type of treatment, analysed the influence of time from fracture to intervention, analysed the influence of comorbidity on mortality, and finally compared survival in patients aged 75 or under and in patients over 75.

Material and methodPatientsAn observational retrospective study was conducted on a consecutive series of 97 patients with primary prostheses treated surgically at our centre for periprosthetic distal femoral fractures between 2007 and 2015.

The inclusion criteria were periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur in patients with a primary knee prosthesis, surgical treatment with internal fixation (plate or intramedullary nail) or revision arthroplasty, and minimal follow-up of 12 months.

The exclusion criteria were patients without follow-up in our hospital and fractures around the tibial or patellar prosthetic component of the arthroplasty.

Lewis and Rorabeck’s classification3 was used to catalogue the fractures, treating 91 of the cases with displaced and stable implant fractures (Lewis and Rorabeck type 2) and 6 of the cases with unstable implant prosthetics (Lewis and Rorabeck type 3). The prosthetic models were: 42 Triathlon Total Knee Replacement System (46.2%) (Stryker Orthopaedics, Mahwah, New Jersey), 14 Vanguard Knee System (15.4%) (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana), 12 PFC SIGMA Knee Systems (13.2%) (Depuy Synthes, Warsaw, Indiana) and 29 Nex-Gen Complete Knee Solution (31.9%) (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana). In all cases, these were hybrid prostheses with cementing of the tibial component. The data analysed were obtained from the patients’ clinical histories.

VariablesWe collected socio-demographic data, age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index,13 type of surgical treatment (intramedullary nail, plate or arthroplasty replacement), the need for bone grafting and the time elapsed between the fracture and the surgery. For the identification of deaths in our cohort during the follow-up period we consulted the national death rate of the Ministry of Health

The results assessed included mortality rates in the first year, in the first 3 years and up to 10 years following the intervention. As secondary objectives, the associated mortality for each type of treatment was compared, the influence of time from fracture to intervention was analysed, the influence of comorbidity on mortality was analysed, and finally survival was compared in patients aged 75 or under and in patients over 75.

Postoperative complications related to the surgical procedure were recorded, including discomfort with the osteosynthetic material, surgical wound infection, refractures and pseudoarthrosis.

Surgical technique and postoperative follow-upThe type of implants used for osteosynthesis were the LISS plate for distal femur (Synthes) or the T2 retrograde nail (Stryker). The rescue prostheses used were the Vanguard 360 Revision Knee System (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana) or the Endomodel Rotational and Hinge Knee prosthesis (Waldemar Link GMBH and Co, Hamburg, Germany). The decision to proceed with internal fixation or replacement of the arthroplasty, as well as the type of implant used, depended on the type of fracture and the prosthetic model implanted. In periprosthetic fractures with a loosened prosthetic component (Lewis and Rorabeck type 3) it is necessary to replace the prosthesis with another model with a stem, regardless of the location of the fracture, adding a bank graft in most cases to replace the bone defect generated when the previous implant was removed. In our series, the use of bank grafting was required in cases with poor bone quality or very comminuted fractures. The surgery was performed when each patient was in an optimal preoperative medical condition.

After the operation, the patients treated with replacement arthroplasty were allowed early weight-bearing as tolerated from the second postoperative day, while patients treated with internal fixation were kept non-weight-bearing an average of 8 weeks, according to the criteria followed by their surgeon during follow-up. Nine patients failed to weight bear on the limb, either due to medical complications or because they were not walking prior to the fracture.

Statistical analysisThe Kaplan-Meier method was used to perform the overall survival analysis, considering the deaths of the patients in the cohort as "events". The Log-Rank method was used to compare survival between age and treatment groups. Statistical significance was established for p values <.05.

ResultsA review of 97 patients with a mean age of 75.1 years, of which 86 were women (88.6%) and 11 were men (11.3%). The mean follow-up was 61.3 months after the surgical intervention (3–130). Regarding comorbidity, 50.5% of patients had some comorbidity, with a mean score of 4.38 on the Charlson index adjusted for age (0–11). The average delay to intervention was 3.1 days (0–10). With respect to the type of surgery, 48 of the patients were operated by open reduction and plate fixation (49.5%), 40 of them with retrograde intramedullary nail (41.2%) and a revision prosthesis was placed in 9 (9.3%). The use of bank grafting was required in 17 cases (17.5%) (Table 1).

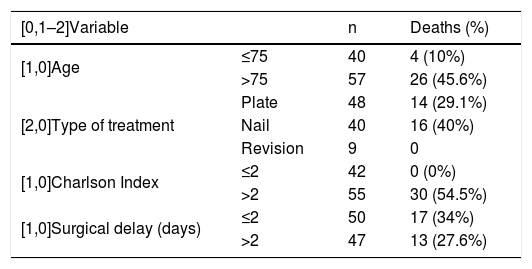

Mortality and survivalThe mortality data are summarised in Tables 2 and 3.

Analysis of mortality by variable.

| [0,1–2]Variable | n | Deaths (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1,0]Age | ≤75 | 40 | 4 (10%) |

| >75 | 57 | 26 (45.6%) | |

| [2,0]Type of treatment | Plate | 48 | 14 (29.1%) |

| Nail | 40 | 16 (40%) | |

| Revision | 9 | 0 | |

| [1,0]Charlson Index | ≤2 | 42 | 0 (0%) |

| >2 | 55 | 30 (54.5%) | |

| [1,0]Surgical delay (days) | ≤2 | 50 | 17 (34%) |

| >2 | 47 | 13 (27.6%) | |

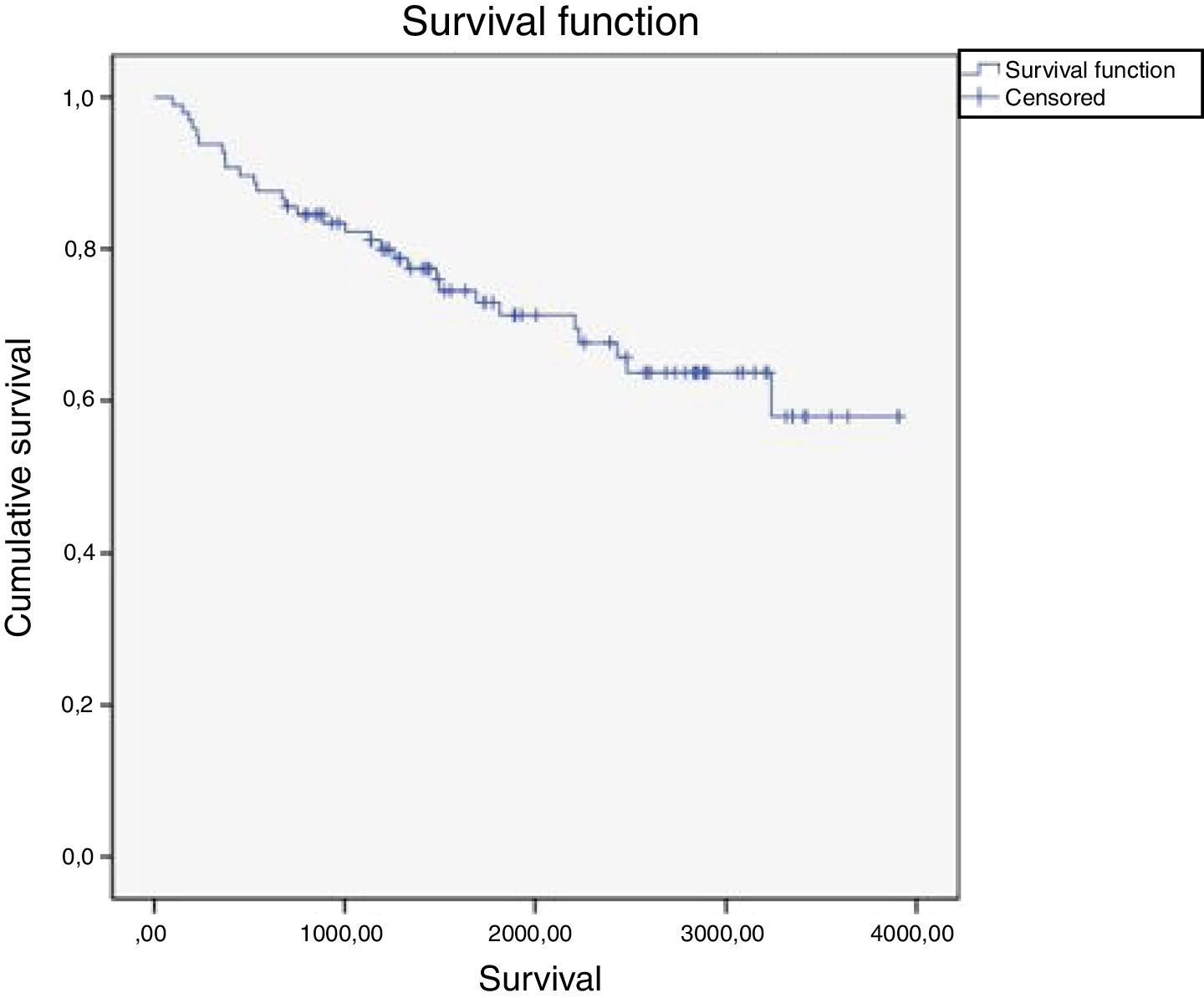

Analysing the overall mortality of our patient series, 30 deaths were recorded out of the total 97 patients during the follow-up period, the mean age of the deaths being 81. A mortality rate of 7.2% was recorded in the first year, 17.5% at 3 years and 30.9% at the 10-year follow-up. Our Kaplan-Maier analysis revealed a decrease in cumulative survival of 92.8% in the first year, 82.3% at the end of 3 years and 57.9% at 10 years. The estimated median survival was 7.9 years (95% confidence interval 7.1–8.7) (Fig. 1).

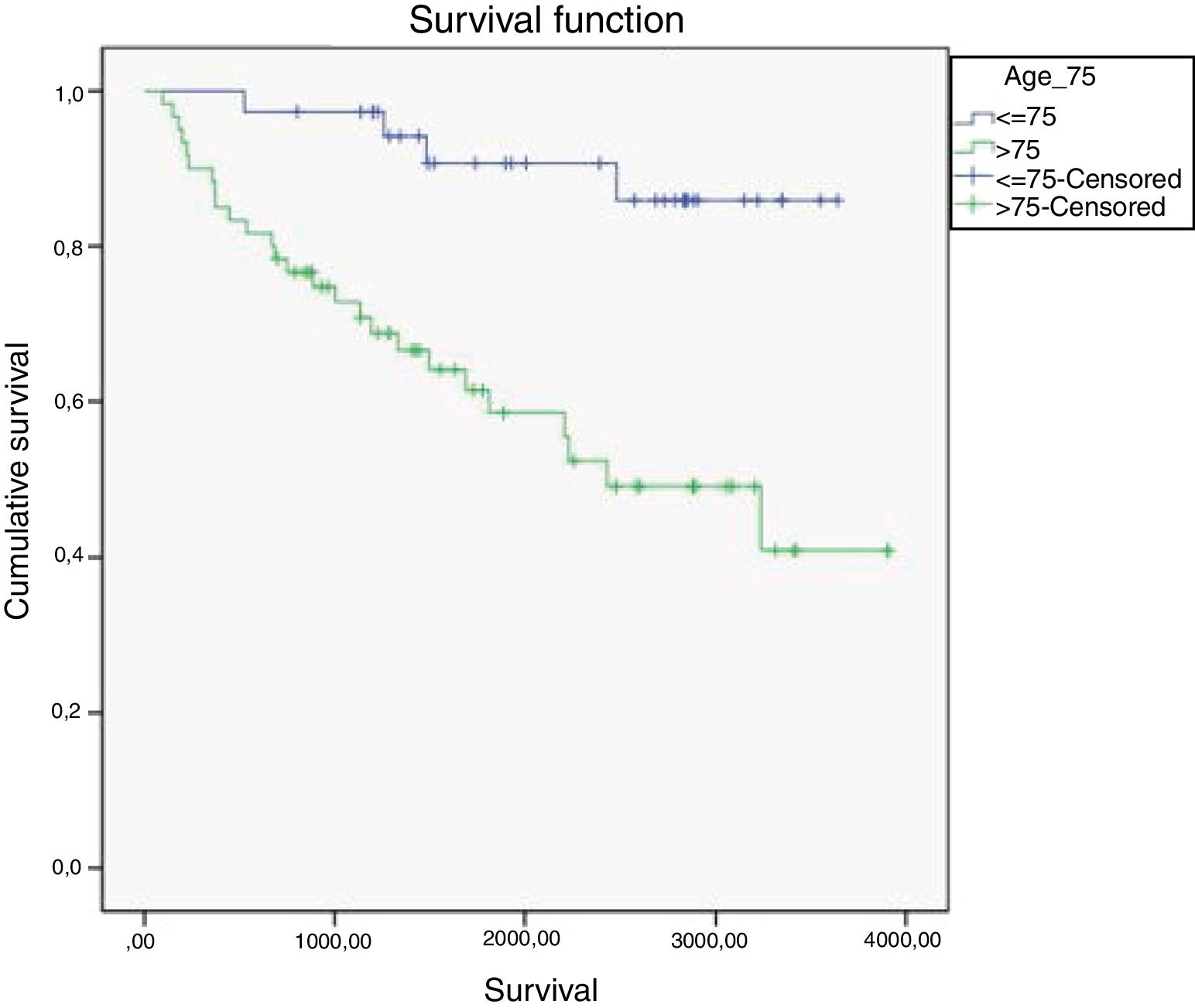

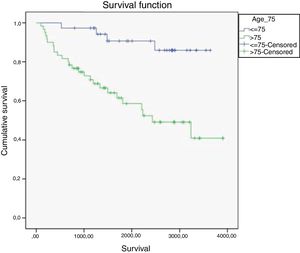

On analysing mortality according to age during the 10-year follow-up we observed that among the 40 patients under 75 there were 4 deaths (10.0%), compared with 26 deaths in the group of 57 patients over the age of 75 (45.6%) (p<.001). Comparing survival between both groups, we observe a more pronounced decrease in survival over time for the patients over 75. After a follow-up of 10 years the probability of survival in those aged under 75 is 85.9% and in those over 75, 40.9%. The differences were statistically significant (p<.001) (Fig. 2).

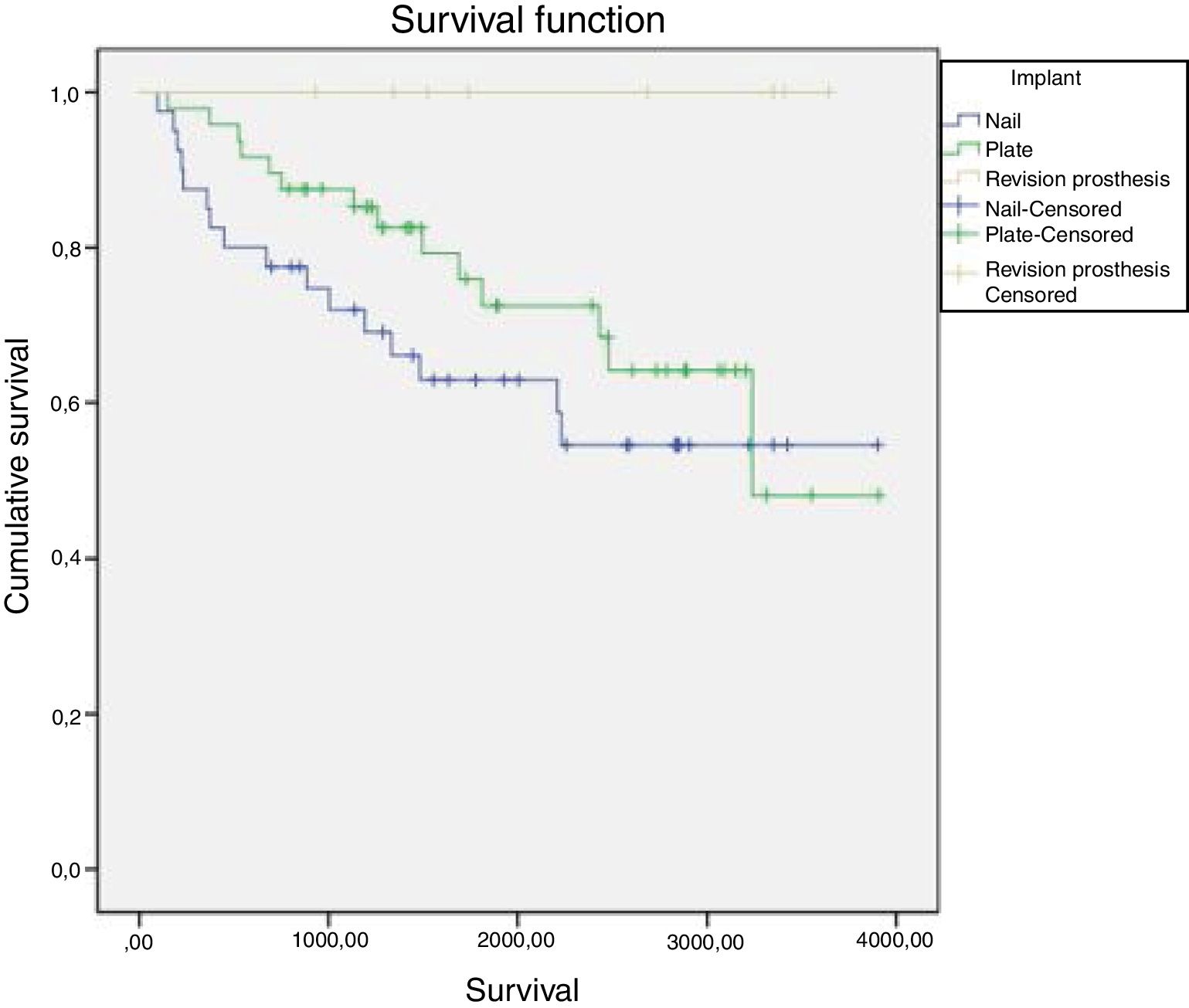

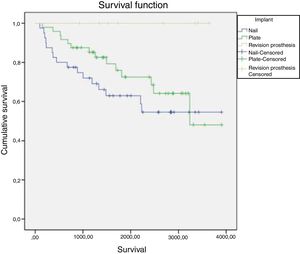

Analysing mortality according to the type of treatment, 14 deaths were recorded in the 48 patients treated with locked plate (29.1%), and 16 deaths were recorded in the 40 patients treated with retrograde nails (40.0%). Survival in both treatment groups decreased similarly over time, although it was somewhat longer in patients treated with a plate than in those treated with nails during almost the entire follow-up period. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p=.055). In the group of patients treated with revision of arthroplasty no deaths were recorded during follow-up (Fig. 3).

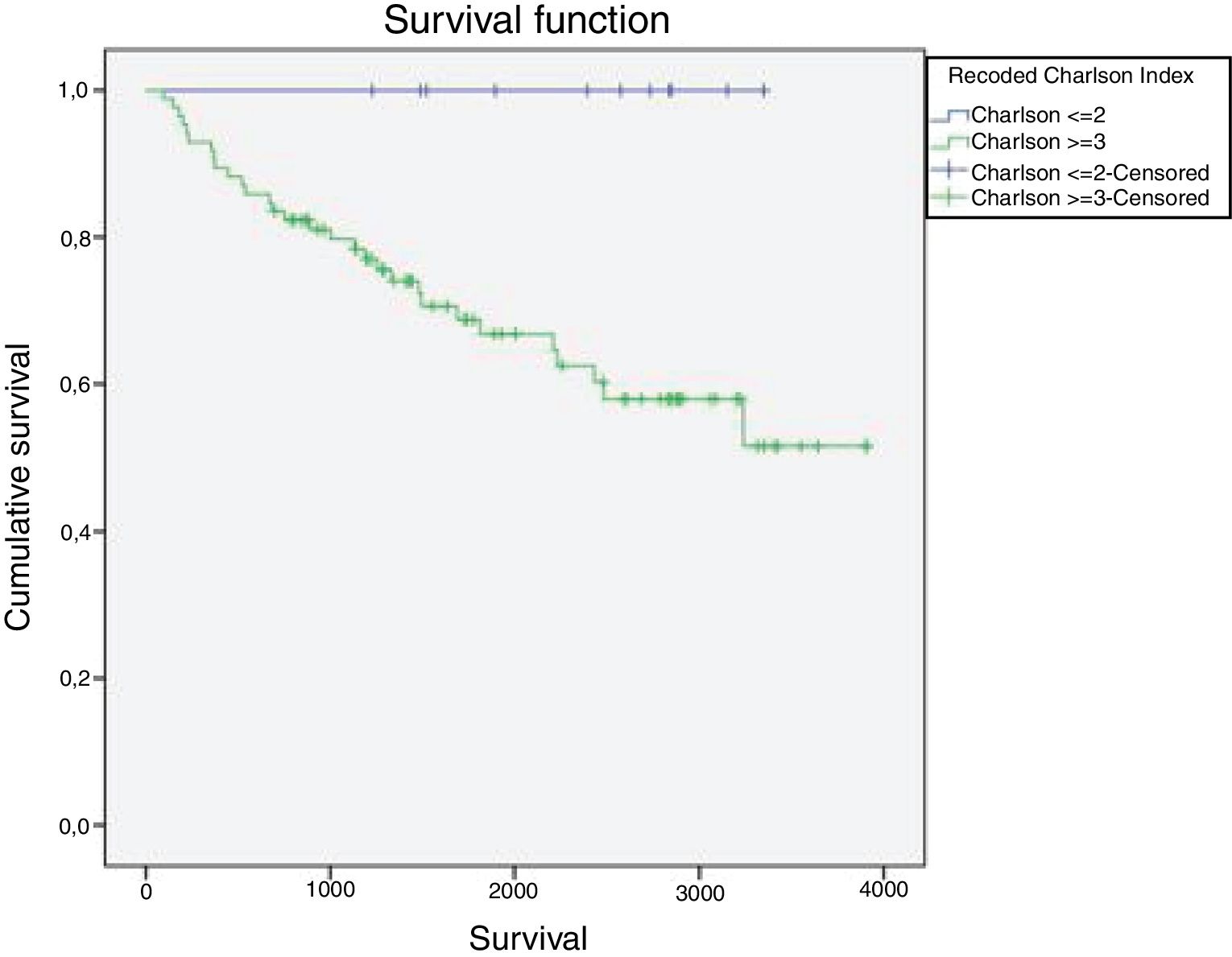

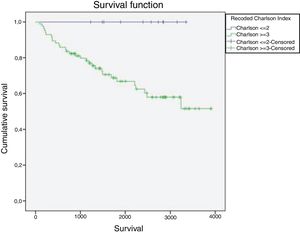

Analysing mortality according to the level of comorbidity, 30 deaths were recorded in the 55 patients with an index greater than or equal to 3 (54.5%), while no deaths were recorded (0%) in the 42 patients with a Charlson index score of less than or equal to 2. These differences were statistically significant (p=.016) (Fig. 4).

Analysing mortality according to the level of comorbidity, 30 deaths were recorded in the 55 patients with an index greater than or equal to 3 (54.5%), while no deaths were recorded (0%) in the 42 patients with a Charlson index score of less than or equal to 2. These differences were statistically significant (p=.016) (Fig. 4).

Reinterventions and complicationsIn terms of main complications, a total of 6 re-interventions for pseudo-arthrosis (6.2%), two cases of peri-implant fractures (2.1%) and one case of surgical wound infection (1.0%) were recorded. All the cases of re-intervention for pseudoarthrosis were for aseptic reasons (four of them occurred in patients operated by plate fixation and two in cases with retrograde intramedullary nail). The two cases of peri-implant fractures occurred in patients with a plate. Finally, there was one case of reintervention due to discomfort with the osteosynthesis material (1.0%) (protrusion of the distal screw into the plate). Due to the retrospective nature of our study, no complications not directly related to the surgical act, such as pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, venous thrombosis, pneumonia, etc. were reported. These variables could not be accurately assessed and were therefore excluded.

DiscussionPeriprosthetic fractures and their treatment represent significant aggression to the patient, and there are high rates of complications described in the literature (between 17% and 71%, depending on the series),1–3,6,7 as well as mortality (between 3% and 58%).2 We must qualify that, despite the high mortality, the mean age of patients who died in our study was 81, therefore, although we consider that the fracture may have been the destabilising element, previous diseases and general condition are also very important.14–16

Periprosthetic fractures occur on average 6.3 years after joint replacement surgery.6 Several studies have reported that periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur may entail a similar or higher mortality risk than hip fractures.6,17 Similarly, Streubel et al.9 showed that distal femoral fractures on total knee arthroplasty carry a significantly higher mortality risk than native distal femoral fractures. This is especially relevant, as recent data have shown that up to half of all distal femoral fractures occur in the presence of a total knee prosthesis. However, Lizar-Utrilla et al.18 conducted a study comparing a group of 28 patients with periprosthetic knee fractures with another group of 28 patients with primary knee arthroplasty and found similar survival and complication rates in both groups after 5 years’ post-operative follow-up.

There are few studies on long-term mortality in periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur. Kolb et al.19 reported 13% mortality in a mean follow-up of 46 months for a group of 23 patients with periprosthetic knee fractures treated with locked-plate fixation. Streubel et al.9 studied a cohort of 48 patients aged over 60 with periprosthetic distal femoral fractures treated with locked femoral plates, and observed mortality rates of 8% at 30 days, of 24% at 6 months, and 27% at one year. Drew et al.20 determined a mortality rate associated with periprosthetic distal femoral fractures of 27%. Another study conducted by Shields et al.21 reported a one-year mortality rate of 18.6% in patients with periprosthetic distal femoral fractures with a mean age of 81. Another study by Hoellwarth et al.1 compared mortality among a group of patients treated with osteosynthesis with plate and another treated with prosthetic replacement, obtaining a mortality at one year of 22% versus 10%, with a mean age of the deceased patients of 85. Gracia Ochoa et al.2 analysed 34 periprosthetic femoral fractures, describing an overall mortality rate of 18%. In our study, the mortality rate was lower at one year, although in the long term the mortality rate was comparable to that recorded in other studies.

Some studies have linked ages 70,22 7823 and 8524 as turning points for increased mortality. We decided to establish two age groups to compare mortality and survival over time using 75 as the cut-off point, observing that mortality at 10 years was much higher for patients over this age. The differences were statistically significant (p<.001). It should also be noted that the associated comorbidity in patients older than 75 was also higher (CCI 5.1 vs. 3.4). In addition, when analysing the influence of comorbidity on mortality, we found that the total number of deaths in our study group occurred in patients with a CCI>2, while no deaths were recorded in patients with a CCI≤2. These differences were statistically significant (p=.16). Therefore, the patient's age and associated comorbidity are factors that will influence mortality following this type of injury.

Studies such as that by Ruder et al.24 and Hoellwarth et al.1 also analysed mortality according to the type of treatment, comparing a group of patients treated with internal fixation with plate versus another group treated with prosthetic replacement, and found no statistically significant differences in mortality rates. Our study also found no statistically significant difference in mortality rates with respect to the surgical method used. In a study by Parrón et al.25 it was concluded that retrograde intramedullary nailing for the treatment of periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur is a technique that provides good results with a low rate of complications.

Prior to surgery for these injuries, a balance must be struck between the need for preoperative clinical optimisation and the risks associated with surgical delay and prolonged bedrest,6,17,26 and some authors propose conservative treatment for low or non-displaced fractures.27 It has been described that a delay in surgery of more than 2 days after the fracture is also associated with increased mortality.1,28 However, in our study we found no statistically significant difference with respect to surgical delay (p=.532).

This study has the limitations of a retrospective study, above all in terms of data collection, as well as being a heterogeneous group in terms of type of fracture and treatment and with a relatively small number of cases, since, although on the increase, periprosthetic fractures are not very frequent. Neither was an exhaustive analysis made of the patients’ functionality and clinical satisfaction following surgery due to the lack of information in some of the clinical histories. However, the main interest of our study was to analyse mortality and survival.

ConclusionsThe management of periprosthetic knee fractures remains a challenge, with very high complication and mortality rates. Patient age and the injury itself are non-modifiable factors that can influence mortality following surgery, while other variables, such as type of osteosynthesis or surgical delay, showed no significant differences in mortality rates in our study

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: García Guirao AJ, Andrés Cano P, Moreno Domínguez R, Giráldez Sánchez M, Cano Luís P. Análisis de la mortalidad tras el tratamiento quirúrgico de las fracturas periprotésicas de fémur distal. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:92–98.