The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of self-administered knee-disability functional assessment questionnaires adapted to Spanish, analysing the quality of the transcultural adaptation procedure and the psychometric properties of the new version.

Material and methodsA search was conducted in the main biomedical databases to find knee-function assessment scales adapted into Spanish, in order to assess their questionnaire adaptation process as well as their psychometric properties.

ResultsTen scales were identified; 3 for lower limb: 2 for any type of pathologies (Lower Limb Functional Index [LLFI]; Lower Extremity Functional Scale [LEFS]) and 1 specific for arthrosis (Arthrosis des Membres Inférieurs et Qualité de vie [AMICAL]); other 3 for knee and hip pathologies (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis [WOMAC] index; Osteoarthritis Knee and Hip Quality of Life [OAKHQOL] questionnaire; Hip and Knee Questionnaire [HKQ]), and other 4 for knee: 2 general scales (Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS]; Knee Society Clinical Rating System [KSS]) and 2 specifics (Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment [VISA-P] questionnaire for patients with patellar tendinopathy and Kujala Score for patellofemoral pain). The transcultural adaptation procedure was satisfactory, albeit somewhat less rigorous for HKQ and LLFI. In no study were all psychometric properties assessed. Reliability was analysed in all cases, except in KSS. Validity was measured in all questionnaires.

ConclusionsThe transcultural adaptation procedure was satisfactory and the psychometric properties analysed were similar to both the original version and other versions adapted to other languages.

Realizar una revisión sistemática de cuestionarios autocumplimentados de valoración funcional para afecciones de rodilla adaptados al español analizando la calidad de la adaptación transcultural y las propiedades psicométricas.

Material y métodosSe realizó una búsqueda en las principales bases de datos biomédicas para localizar escalas de valoración funcional de rodilla adaptadas al español, evaluando el proceso de adaptación y sus propiedades psicométricas.

ResultadosSe identificaron 10 escalas; 3 fueron para miembro inferior: 2 para cualquier tipo de afección (Lower Limb Functional Index [LLFI]; Lower Extremity Functional Scale [LEFS]) y una específica para artrosis (Arthrose des Membres Inférieurs et Qualité de vie [AMICAL]); otras 3 para patologías de rodilla y cadera (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis [WOMAC] index; Osteoarthritis Knee and Hip Quality of Life [OAKHQOL] questionnaire; Hip and Knee Questionnaire[HKQ]), y otras 4 para rodilla: 2 generales (Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS]; Knee Society Clinical Rating System [KSS]) y 2 específicas (Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment [VISA-P] questionnaire para pacientes con tendinopatía rotuliana y Kujala Score para el dolor femoropatelar). El procedimiento de adaptación transcultural fue satisfactorio, aunque algo menos riguroso para los cuestionarios HKQ y LLFI. En ningún estudio se evaluaron todas las propiedades psicométricas. La fiabilidad se analizó en todos los casos, menos en el KSS. La validez se midió en todos los cuestionarios.

ConclusiónLas propiedades psicométricas analizadas fueron aceptables y similares a la versión original y a otras versiones adaptadas a otros idiomas.

Correct functional evaluation is essential in the management of knee pathologies to evaluate clinical changes and the effects of treatment. This evaluation may use functional scales which report on the impact of the disease from the patient's point-of-view.1

There are a large number of scales, usually in the form of self-administered questionnaires that measure function and symptoms in a range of knee pathologies.2 Some of these are applicable to any lower member complaint, including the knee. Others are designed exclusively for the knee area, either in general (for any pathology), or for specific conditions.

Several papers have recently been published which revise the scales that can be used for knee problems.3,4 No similar reviews have been published for knee pathology questionnaires in Spanish.

Spanish is the most widely spoken language in the world after Mandarin Chinese, and the number of speakers is rising. In 2015 almost 470 million people spoke it as their native tongue (6.7% of world population).5 However, the majority of these scales were developed in Anglo-Saxon countries, leading to drawbacks when they are used in countries with other languages or cultures. The need to apply these scales in patients with a different culture requires suitable cross-cultural adaptation to ensure they mean the same as in their original version.6,7 Additionally, the psychometric properties of the new version must be analysed to ensure that the tool is equivalent to the original.8

Our review aims to carry out an exhaustive bibliographical search of self-administered knee questionnaires that have been translated into Spanish, analysing the methodological quality of the cross-cultural adaptation process and the psychometric properties of the Spanish version.

Material and methodsSearch strategyA systematic revision was undertaken of papers published on the cross-cultural adaptation into Spanish of self-administered questionnaires to evaluate knee patients, together with the validation process in our language. A bibliographical search of international electronic data bases was conducted (Medline, Embase, CINAHL and Web of Science) from their creation until 31 May 2016. The terms used and the search strategy in Medline were as follows: “outcome” or “questionnaire” or “score” or “functional scale” or “assessment tool” or “instruments” and “knee” or “disability” or “lower limb” and “Spanish” or “Spanish version” or “Spanish cultural adaptation” or “Spanish assessment” or “Spanish translation” or “cross-cultural adaptation” or “validation”. A manual search was also undertaken using the names of the different knee scales as key words in the different data bases. The web was searched too, including Google Scholar, with the aim of being able to include other types of publication, such as grey literature. Finally, the references in the papers obtained were examined manually.

Selection criteria2 authors reviewed the title and abstract of each paper found. If their reading suggested that it could be selected, the complete paper was read. We include papers, without any linguistic restriction, on studies that described the process of cross-cultural adaptation into Spanish of self-administered questionnaires to functionally evaluate patients with knee complaints. They also analysed the psychometric properties of the new version. Papers that only analyse the properties of a previously adapted questionnaire, research protocols and congress summaries were excluded.

Data analysis2 authors classified and analysed the results of the selected papers. If any discrepancy arose an attempt was made to seek a consensus, and when necessary a third reviewer was called in. Data analysis included:

The characteristics of the participants in the study. The data of the patients included in the study were recorded: country and town, total number of patients included, diagnosis, age and sex. They were checked to ensure that they included at least 50 patients, as this is the minimum number recommended for cross-cultural adaptation studies.9,10

Evaluation of the methodology used to carry out cross-cultural adaptation. Studies were checked to ensure that they contained the 5 steps which are usually recommended in the international bibliography6,9,10 and that these had been correctly implemented. These 5 steps are: (1) direct translation of the original questionnaire into Spanish (carried out independently by at least 2 bilingual translators whose native language is Spanish); (2) a synthesis of translations and the resolution of any possible discrepancies between the translators with a member of the research team; (3) reverse or back-translation of the agreed translation into Spanish back to the original language, independently by at least 2 translators who did not know the said original version; (4) revision by a committee of experts to develop the penultimate version, ensuring the semantic, idiomatic, experiential and conceptual equivalence of the scale; and (5) a pilot trial (pre-test) of the penultimate version of the questionnaire with Spanish-speaking subjects. It is recommended that this trial ideally should include 30–40 individuals, seeking items that are not answered and possible comprehension problems. In each one of these steps the question will be asked as to whether it had been carried out correctly or not, whether it had not been carried out, or whether the authors failed to supply the necessary information.

Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Spanish version. The following aspects were analysed: reliability, validity and sensitivity to the change.6,10–13 Reliability evaluates the exactitude or precision of the instrument and includes internal consistency, test–retest reproducibility and agreement. Internal consistency is calculated using Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient. When the instrument is composed of subscales, the correlation between the items in each domain has to be calculated with the total scale. Factorial analysis is used to determine the dimensionality of the items. Test–retest reproducibility is calculated by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Agreement is measured using the standard error of measurement (SEM) and the minimal detectable change (MDC90). Validity is measured using correlation coefficients such as Pearson's or Spearman's, and correlation may be direct, indirect or absent. Floor and ceiling effects refer to the percentage of subjects who obtain the lowest and highest possible scores. These must not surpass 15% of those who answer, as otherwise this restricts the validity of the scale content as patients with extreme values cannot be distinguished from each other. Sensitivity is the capacity of the instrument to detect clinically important changes over time. The minimum detectable change is mainly measured by effect size (ES) and the standardised response mean (SRM).

Evaluation of the direct applicability of the scales adapted to one Spanish-speaking country for use in another. The adaptations made in Latin American countries were analysed to see whether modifications to them would be required for use in Spain, and vice versa.

ResultsThe bibliographical search carried out led to the identification of 10 relevant papers.14–23 10 self-administered questionnaires were found that had been translated and transculturally adapted to the Spanish population, after which the clinimetric properties of the new version had been studied. In all cases except 2 the original questionnaire had been developed in English: the questionnaires Arthrose des Membres Inférieurs et Qualité de vie (AMICAL)14 and the Osteoarthritis Knee and Hip Quality of Life (OAKHQOL) questionnaire19 were developed in French. 3 questionnaires were applicable to lower limb pathologies: 2 for any type of complaint (Lower Limb Functional Index [LLFI]20 and the Lower Extremity Functional Scale [LEFS]21) while one was specifically for arthrosis (AMICAL).14 3 other questionnaires applicable to knee and hip pathologies were found: the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index17; OAKHQOL19 and the Hip and Knee Questionnaire (HKQ).15 There were 2 general knee questionnaires: the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)16 and the Knee Society Clinical Rating System (KSS).18 Finally, 2 questionnaires were found on specific knee conditions: the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment (VISA-P) questionnaire23 for patella tendinopathy, and the Kujala Score23 for patients with patellofemoral pain. It must be said that our search found no questionnaire that had been originally developed in Spanish.

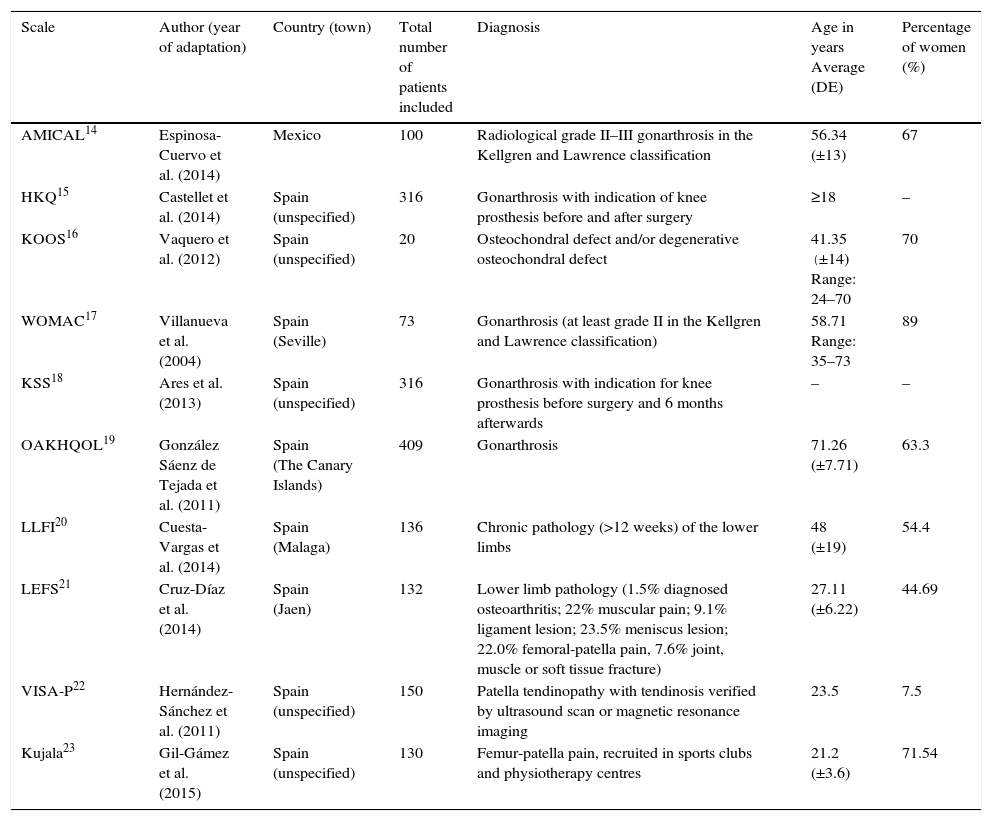

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the population in which each one of the papers was prepared.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the population in studies of cross-cultural adaptation.

| Scale | Author (year of adaptation) | Country (town) | Total number of patients included | Diagnosis | Age in years Average (DE) | Percentage of women (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMICAL14 | Espinosa-Cuervo et al. (2014) | Mexico | 100 | Radiological grade II–III gonarthrosis in the Kellgren and Lawrence classification | 56.34 (±13) | 67 |

| HKQ15 | Castellet et al. (2014) | Spain (unspecified) | 316 | Gonarthrosis with indication of knee prosthesis before and after surgery | ≥18 | – |

| KOOS16 | Vaquero et al. (2012) | Spain (unspecified) | 20 | Osteochondral defect and/or degenerative osteochondral defect | 41.35 (±14) Range: 24–70 | 70 |

| WOMAC17 | Villanueva et al. (2004) | Spain (Seville) | 73 | Gonarthrosis (at least grade II in the Kellgren and Lawrence classification) | 58.71 Range: 35–73 | 89 |

| KSS18 | Ares et al. (2013) | Spain (unspecified) | 316 | Gonarthrosis with indication for knee prosthesis before surgery and 6 months afterwards | – | – |

| OAKHQOL19 | González Sáenz de Tejada et al. (2011) | Spain (The Canary Islands) | 409 | Gonarthrosis | 71.26 (±7.71) | 63.3 |

| LLFI20 | Cuesta-Vargas et al. (2014) | Spain (Malaga) | 136 | Chronic pathology (>12 weeks) of the lower limbs | 48 (±19) | 54.4 |

| LEFS21 | Cruz-Díaz et al. (2014) | Spain (Jaen) | 132 | Lower limb pathology (1.5% diagnosed osteoarthritis; 22% muscular pain; 9.1% ligament lesion; 23.5% meniscus lesion; 22.0% femoral-patella pain, 7.6% joint, muscle or soft tissue fracture) | 27.11 (±6.22) | 44.69 |

| VISA-P22 | Hernández-Sánchez et al. (2011) | Spain (unspecified) | 150 | Patella tendinopathy with tendinosis verified by ultrasound scan or magnetic resonance imaging | 23.5 | 7.5 |

| Kujala23 | Gil-Gámez et al. (2015) | Spain (unspecified) | 130 | Femur-patella pain, recruited in sports clubs and physiotherapy centres | 21.2 (±3.6) | 71.54 |

AMICAL: Arthrose des Membres Inférieurs et Qualité de vie; SD: standard deviation; HKQ: Hip and Knee Questionnaire; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; KSS: Knee Society Clinical Rating System; LEFS: Lower Extremity Functional Scale; LLFI: Lower Limb Functional Index; OAKHQOL: Osteoarthritis Knee and Hip Quality of Life questionnaire; VISA-P: Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment questionnaire; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis index.

The adapted scales, together with the instructions for the patient, are included in the publication in all cases except for 3 questionnaires: the KOOS,16 the WOMAC17 and the KSS.18 The majority of the papers were published very recently. One of the adaptations was published in 2015,23 4 were published in 2014,14,15,20,21 one was published in 201318 and another dates from 2012.16 The first scale to be adapted to Spanish was the WOMAC, in 2004.17 It must be pointed out that this scale was translated into Spanish for the first time in 1999,24 but as the psychometric properties study was not included, it was excluded from our selection of papers.

All of the questionnaires were validated in Spain except one (AMICAL)14 that was validated in Mexico. In all of the adaptations except for one,16 the number of patients was greater than the minimum recommended number of 50 for studies of this type.

In general the cross-cultural adaptation process in all of the scales required modifications to the original version, although they were not very important.

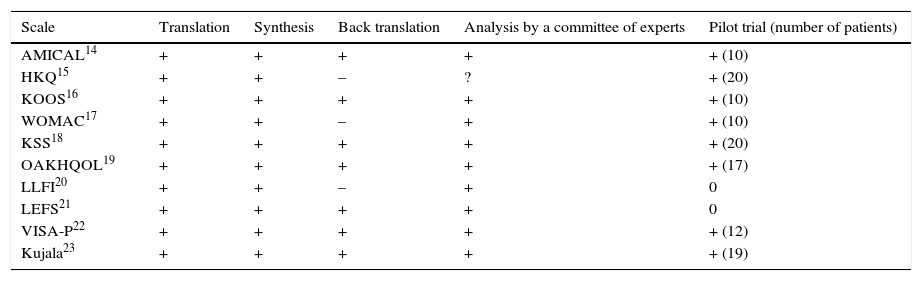

The main findings of the evaluation of the methodology used for cross-cultural adaptation are analysed in Table 2.

Evaluation of the methodology used for the cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaires.

| Scale | Translation | Synthesis | Back translation | Analysis by a committee of experts | Pilot trial (number of patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMICAL14 | + | + | + | + | + (10) |

| HKQ15 | + | + | – | ? | + (20) |

| KOOS16 | + | + | + | + | + (10) |

| WOMAC17 | + | + | – | + | + (10) |

| KSS18 | + | + | + | + | + (20) |

| OAKHQOL19 | + | + | + | + | + (17) |

| LLFI20 | + | + | – | + | 0 |

| LEFS21 | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| VISA-P22 | + | + | + | + | + (12) |

| Kujala23 | + | + | + | + | + (19) |

+: correctly performed; ?: doubtful; –: incorrectly performed or not performed; 0: no information is given as to whether it was performed or not; AMICAL: Arthrose des Membres Inférieurs et Qualité de vie; HKQ: Hip and Knee Questionnaire; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; KSS: Knee Society Clinical Rating System; LEFS: Lower Extremity Functional Scale; LLFI: Lower Limb Functional Index; OAKHQOL: Osteoarthritis Knee and Hip Quality of Life questionnaire; VISA-P: Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment questionnaire; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis index.

Six questionnaires rigorously complied with the 5 steps of the recommendations for international guides.14,16,18,19,22,23 The other questionnaires complied less strictly with this aspect. Although the pilot trial took place for 8 scales,14–19,22,23 in no case did this occur with more than 30 subjects.

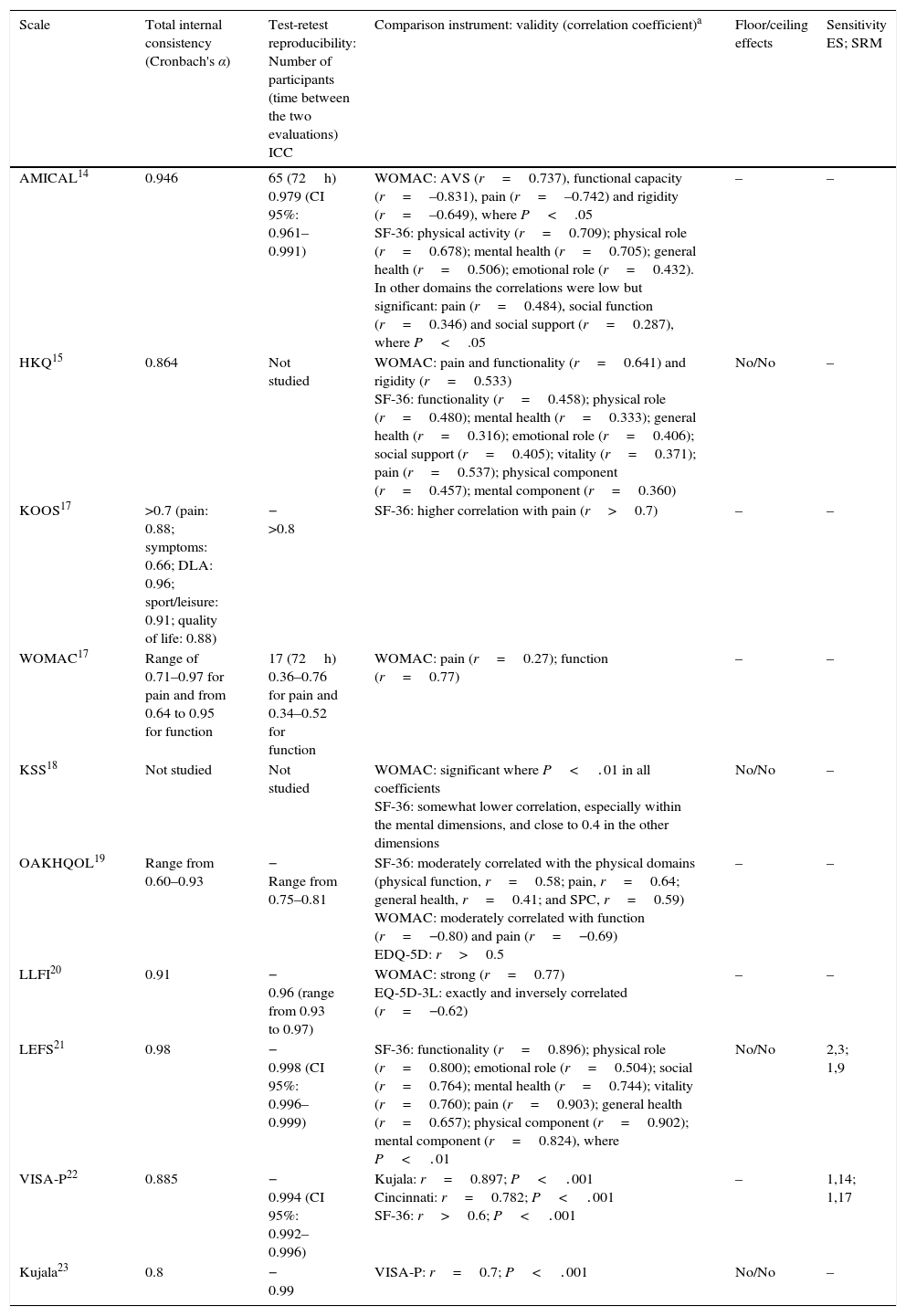

The main psychometric properties analysed in the Spanish versions are shown in Table 3. No work evaluated all of the metric properties of the new version. In general, the authors of each one of the adaptations concluded that the psychometric properties evaluated were acceptable and comparable with those of the original versions and other versions adapted to other languages.

The main psychometric properties analysed in the adapted questionnaires.

| Scale | Total internal consistency (Cronbach's α) | Test-retest reproducibility: Number of participants (time between the two evaluations) ICC | Comparison instrument: validity (correlation coefficient)a | Floor/ceiling effects | Sensitivity ES; SRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMICAL14 | 0.946 | 65 (72h) 0.979 (CI 95%: 0.961–0.991) | WOMAC: AVS (r=0.737), functional capacity (r=–0.831), pain (r=–0.742) and rigidity (r=–0.649), where P<.05 SF-36: physical activity (r=0.709); physical role (r=0.678); mental health (r=0.705); general health (r=0.506); emotional role (r=0.432). In other domains the correlations were low but significant: pain (r=0.484), social function (r=0.346) and social support (r=0.287), where P<.05 | – | – |

| HKQ15 | 0.864 | Not studied | WOMAC: pain and functionality (r=0.641) and rigidity (r=0.533) SF-36: functionality (r=0.458); physical role (r=0.480); mental health (r=0.333); general health (r=0.316); emotional role (r=0.406); social support (r=0.405); vitality (r=0.371); pain (r=0.537); physical component (r=0.457); mental component (r=0.360) | No/No | – |

| KOOS17 | >0.7 (pain: 0.88; symptoms: 0.66; DLA: 0.96; sport/leisure: 0.91; quality of life: 0.88) | − >0.8 | SF-36: higher correlation with pain (r>0.7) | – | – |

| WOMAC17 | Range of 0.71–0.97 for pain and from 0.64 to 0.95 for function | 17 (72h) 0.36–0.76 for pain and 0.34–0.52 for function | WOMAC: pain (r=0.27); function (r=0.77) | – | – |

| KSS18 | Not studied | Not studied | WOMAC: significant where P<.01 in all coefficients SF-36: somewhat lower correlation, especially within the mental dimensions, and close to 0.4 in the other dimensions | No/No | – |

| OAKHQOL19 | Range from 0.60–0.93 | − Range from 0.75–0.81 | SF-36: moderately correlated with the physical domains (physical function, r=0.58; pain, r=0.64; general health, r=0.41; and SPC, r=0.59) WOMAC: moderately correlated with function (r=−0.80) and pain (r=−0.69) EDQ-5D: r>0.5 | – | – |

| LLFI20 | 0.91 | − 0.96 (range from 0.93 to 0.97) | WOMAC: strong (r=0.77) EQ-5D-3L: exactly and inversely correlated (r=−0.62) | – | – |

| LEFS21 | 0.98 | − 0.998 (CI 95%: 0.996–0.999) | SF-36: functionality (r=0.896); physical role (r=0.800); emotional role (r=0.504); social (r=0.764); mental health (r=0.744); vitality (r=0.760); pain (r=0.903); general health (r=0.657); physical component (r=0.902); mental component (r=0.824), where P<.01 | No/No | 2,3; 1,9 |

| VISA-P22 | 0.885 | − 0.994 (CI 95%: 0.992–0.996) | Kujala: r=0.897; P<.001 Cincinnati: r=0.782; P<.001 SF-36: r>0.6; P<.001 | – | 1,14; 1,17 |

| Kujala23 | 0.8 | − 0.99 | VISA-P: r=0.7; P<.001 | No/No | – |

AMICAL: Arthrose des Membres Inférieurs et Qualité de vie; DLA: daily life activities; SPC: summarised physical component; EQ-5D-3L: European Health Questionnaire 5 Dimensions 3 Levels; ES: effect size; AVS: analogue visual scale; HKQ: Hip and Knee Questionnaire; CI: confidence interval; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; KSS: Knee Society Clinical Rating System; LEFS: Lower Extremity Functional Scale; LLFI: Lower Limb Functional Index; OAKHQOL: Osteoarthritis Knee and Hip Quality of Life questionnaire; SF-36: Short Form 36 Health Survey; SRM: standardised response mean; VISA-P: Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment questionnaire; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis index.

For reliability, internal consistency was evaluated in all of the scales except one,18 test–retest reproducibility was evaluated in all of them except in 2,15,18 and agreement was only analysed in 2 scales.20,21 When the test–retest was performed, only 2 scales14,17 indicate the number of participants while only one14 included more than the ideal number of more than 29 patients which is recommended for this evaluation. The total internal consistency in all of the scales except one19 was >0.7–0.8, a sufficient value to guarantee their reliability. The ICC was very good in all cases. Agreement was analysed in 2 questionnaires.20,21 Cruz-Díaz et al.21 analysed the value of MDC95, which was 2.18, and the SEM, which was 0.88. Cuesta-Vargas et al.20 calculated the MDC90 value and the SEM value, which were 7.12 and 3.12%, respectively. Validity was evaluated in all of the questionnaires. This varied depending on the instruments used for comparison, although it was generally suitable.

The floor and ceiling effects were only analysed in 4 questionnaires,15,18,20,23 and they were not found in any of them. Sensitivity was only examined in 2 scales.20,22 In these, values were obtained for ES and SRM that indicated high sensitivity in both cases.

DiscussionAn essential aspect of treatment result evaluation systems is that the patient himself, using questionnaires, evaluates the results obtained from his own point of view. Even if the measurements taken by the clinic correlate poorly with the patient's perceived disability, this is one of the most important aspects for the latter.25 This is why questionnaires are tools that complement clinical examination. Many questionnaires have been prepared at an international level to evaluate knee complaints as perceived by the patients themselves. Each one has advantages and disadvantages in comparison with the others, and it is unclear whether any of them is better than the others. This matter is arousing increasing interest, and many revisions have been published in recent years.2–4 The majority of questionnaires have been developed in Anglo-Saxon countries. It is preferable to adapt an existing scale, checking that the new version keeps the psychometric properties of the original, rather than creating a new scale. The latter option costs more in time and money, and increases the diversity of questionnaires. Using the same scale makes it easier to compare different populations.

The aim of our work was to undertake a systematic review of self-administered knee questionnaires adapted into Spanish, analysing the methodological quality of the cross-cultural adaptation process as well as the psychometric properties of the resulting new version. We found 10 papers14–23 on 10 questionnaires, 5 of which were published in the last 2 years.14,15,20,21,23

Three questionnaires are applicable to lower limb pathologies: 2 are for any type of complaint (LLFI20 and LEFS21) and one is for arthrosis (AMICAL).14 Three are for knee and hip pathologies: WOMAC,17 OAKHQOL19 and HKQ.15 Four are for knee pathologies: 2 general ones (KOOS16 and KSS18) and 2 specific ones (VISA-P22 for patella tendinopathy, and Kujala23 for patients with patellofemoral pain). Transcultural adaptations into other languages are available for all of them.

There is still no clear international agreement on the best way of implementing cross-cultural adaptation.6 There does seem to be agreement on the need for back or retrotranslation and a pilot trial (pre-test).6 The internationally recognised criteria for the process of adaptation into Spanish were followed with maximum rigour for 6 questionnaires,14,16,18,19,22,23 although the others may also be considered to be methodologically valid. Nevertheless, the process was somewhat less rigorous for the HKL and LLFI questionnaires. In different Spanish-speaking nations or populations there may be words that are only used there, or which differ in meaning between countries or cultural groups. However, in general cultural differences are not so strong that they would hinder the use of these questionnaires in different Spanish-speaking countries. In the AMICAL questionnaire, which was adapted in Mexico,14 the insertion of small changes in some of the words used would make it possible to use it in Spain. For example, “auto” could be replaced by “coche” or “pesero” could be replaced by “autobús”.

The psychometric properties analysed are appropriate in all of the scales and in general are similar to those in the original version and other versions of the scale adapted to other languages. To select which questionnaire to use in a specific situation practical considerations should therefore apply, such as the time needed to complete and grade it, as well as its usefulness for specific pathologies.

A possible limitation of our study is that due to their complexity we did not use the verification list proposed by the COSMIN13 group or the EMPRO26 tool. These are recommended to check the correct validation of the psychometric properties in a questionnaire. The strong points of our review are firstly that the rigour of the questionnaire adaptation process and psychometric properties studied were analysed by 2 authors. Additionally, the search process was very exhaustive, so that it is highly improbable that other scales which have been adapted for use in Spanish were not found.

To conclude, the cross-cultural adaptation process into Spanish was satisfactory in all 10 questionnaires. The psychometric properties of the new versions were acceptable and similar to those of the original questionnaires and other versions adapted into other languages.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe protection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were conducted in human beings or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this paper.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Valero S. Revisión sistemática de los cuestionarios autocumplimentados adaptados al español para la valoración funcional de pacientes con afecciones de rodilla. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:96–103.