To evaluate the efficiency of a clinical pathway in the management of elderly patients with fragility hip fracture in a second level hospital in terms of length of stay time to surgery, morbidity, hospital mortality, and improved functional outcome.

Material and methodsA comparative and prospective study was carried out between two groups of patients with hip fracture aged 75 and older prior to 2010 (n=216), and after a quality improvement intervention in 2013 (n=196). A clinical pathway based on recent scientific evidence was implemented. The degree of compliance with the implemented measures was quantified.

ResultsThe characteristics of the patients in both groups were similar in age, gender, functional status (Barthel Index) and comorbidity (Charlson Index).

Median length of stay was reduced by more than 45% in 2013 (16.61 days vs. 9.08 days, p=0.000). Also, time to surgery decreased 29.4% in the multidisciplinary intervention group (6.23 days vs. 4.4 days, p=0.000). Patients assigned to the clinical pathway group showed higher medical complications rate (delirium, malnutrition, anaemia and electrolyte disorders), but a lower hospital mortality (5.10% vs. 2.87%, p>0.005). The incidence of surgical wound infection (p=0.031) and functional efficiency (p=0.001) also improved in 2013. An increased number of patients started treatment for osteoporosis (14.80% vs. 76.09%, p=0.001) after implementing the clinical pathway.

ConclusionThe implementation of a clinical pathway in the care process of elderly patients with hip fracture reduced length of stay and time to surgery, without a negative impact on associated clinical and functional outcomes.

Evaluar la eficiencia de una vía clínica en el manejo del paciente geriátrico con fractura de cadera por fragilidad en un hospital de segundo nivel, en términos de estancia total, prequirúrgica y morbimortalidad intrahospitalaria y resultado funcional.

Material y métodosEstudio comparativo prospectivo entre dos grupos de pacientes (2010, n=216 y 2013, n=196) con fractura de cadera ≥ 75 años, antes y después de la puesta en marcha de un plan de mejora, consistente en la aplicación de medidas multidisciplinares actualizadas de acuerdo con la evidencia científica reciente. Se registra el grado de cumplimiento de las medidas implantadas.

ResultadosLas características de los pacientes de ambos grupos fueron similares en edad, sexo, situación funcional (Índice de Barthel) y comorbilidad (Charlson).

En 2013 disminuyó la estancia media un 45% (16,61 días en 2010 vs. 9,08 días en 2013, p=0,000) y la estancia prequirúrgica un 29,4% (6,23 vs. 4,4 días, p=0,000). Se registraron mayores tasas de complicaciones médicas (delirium, desnutrición, anemia y trastornos electrolíticos) con una menor mortalidad intrahospitalaria posquirúrgica (5,10% vs. 2,87, p>0,005). La incidencia de infección de herida quirúrgica (p=0,031) y la eficiencia funcional (p=0,001) también mejoraron en 2013. Mayor número de pacientes iniciaron tratamiento para la osteoporosis (14,80 vs. 76, 09%, p=0,001) tras la vía clínica.

ConclusiónLa aplicación de una vía clínica en el manejo del paciente anciano con fractura de cadera proporciona una reducción de la estancia hospitalaria global y prequirúrgica, sin repercusión clínica y funcional negativa.

Hip fracture (FC) is a prevalent pathology among the elderly population, with over 85% of cases occurring in patients aged over 65 years. It is the most common cause for trauma-related hospitalisation in this population group.1 It has repercussions at multiple levels due to the associated impact on quality of life and morbidity and mortality. It is the osteoporotic fracture with the highest rate of mortality, with percentages between 2% and 7% during the acute phase and up to 45% at 12 months after the episode, according to some series. After suffering a HF, patients have an increased relative risk of mortality between 2 and 3 times higher than the rest of the population with the same age and gender.2 Half of those deaths occur during the first 6 months and are related to a worsening of a poor baseline condition, rather than the onset of severe postoperative complications.2

A study conducted in our country estimated that the cost per process during hospitalisation ranged between 10,590 and 15,573 euros.3 Since the acute phase accounts for up to 43% of the total stay (acute phase, functional recovery unit and stay at nursing homes),4 the secondary cost of institutionalisation should be added to that expense.

Several models for collaboration between Orthopaedics and Geriatrics Services5 have been described in order to improve the treatment of these patients (referral on demand, consultation and creation of Orthogeriatrics Units). However, Orthogeriatrics Units (OGU), with a greater level of coordination and involvement by trauma specialists, geriatricians and other professionals, with shared responsibility and joint decisions, have shown the greatest benefit in terms of reduction of overall stay and time to surgery, with less complications and mortality and greater access to rehabilitation, as well as lower economic costs.3,6–9

From the standpoint of overall health recovery, the benefit of multidisciplinary management has been extensively proven. Therefore, at present, the main clinical practice guidelines10–13 recommend (grade A recommendation) that hospitals treating patients aged over 65 years with HF should offer programmes including early multidisciplinary evaluation by a team of geriatricians.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficiency of a clinical pathway for the management of geriatric patients with HF due to fragility at a second level hospital, in terms of overall stay, time to surgery and in-hospital morbidity and mortality.

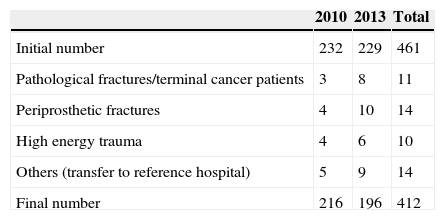

Materials and methodA comparative, longitudinal, analytical study was designed, with monitoring of prevalence and prospective data collection. The study had a quasi-experimental intervention (before and after), comparing patients admitted between 1 January and 31 December 2010 (control group) vs. those admitted in 2013, after a quality improvement intervention (study group). We included patients admitted at the Ávila Complejo Asistencial (second level hospital) due to HF by fragility, aged 75 years or over, and excluded those with pathological or periprosthetic fractures, and those secondary to high energy trauma, as well as terminal cancer patients (Table 1).

As sources of information, we used the electronic medical histories of patients, the information system of hospital activity and the basic minimum dataset.

The variables recorded covered epidemiological, clinical and functional information, as well as social status, level of dependence, functional efficiency and drug therapy upon admission and discharge. In addition, we also registered surgical delays over 72h, complications, in-hospital mortality and changes of location upon discharge.

The information was recorded in a questionnaire created for that purpose by two of the authors (orthopaedist and geriatrician).

Quantitative variables were expressed through mean and standard deviation, whilst qualitative variables were described through frequency tables and percentages. The two groups were compared by means of a bivariate analysis. Qualitative variables were compared by means of contingency tables with the Chi-squared statistic and Yates correction when necessary. The behaviour of quantitative variables was studied by means of parametric tests (Student t) when the variables adjusted to a normal distribution, and with a non-parametric test when they did not. The power and precision of the association were calculated through the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

The statistical analysis was carried out using the software package SPSS® version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), accepting the existence of statistically significant differences with an alpha error <0.05.

During 2011, a multidisciplinary team led by Geriatrics and Orthopaedics was established, which included other professionals associated to healthcare for elderly patients with hip fractures: Anaesthesiology, Emergencies, Haematology, Rehabilitation and Nursing staff from the care units involved. The improvement strategy was agreed and documented15 according to the scientific evidence14 and the resources available at the centre. It was communicated to the rest of professionals involved throughout 2012 and was put into effect in 2013. Subsequently, the level of compliance with each of the protocols considered in the intervention group was evaluated.

From the standpoint of daily practice, the model of orthogeriatrics collaboration developed at Ávila H.C. is comparable to an OGU, with the difference that, due to organisational aspects, it was not possible to have beds reserved exclusively for a specific type of patients. The quality improvement plan had the main pillar of daily and continued geriatrics care, with shared responsibility between a geriatrician and a orthopaedist from the moment of admission until discharge.

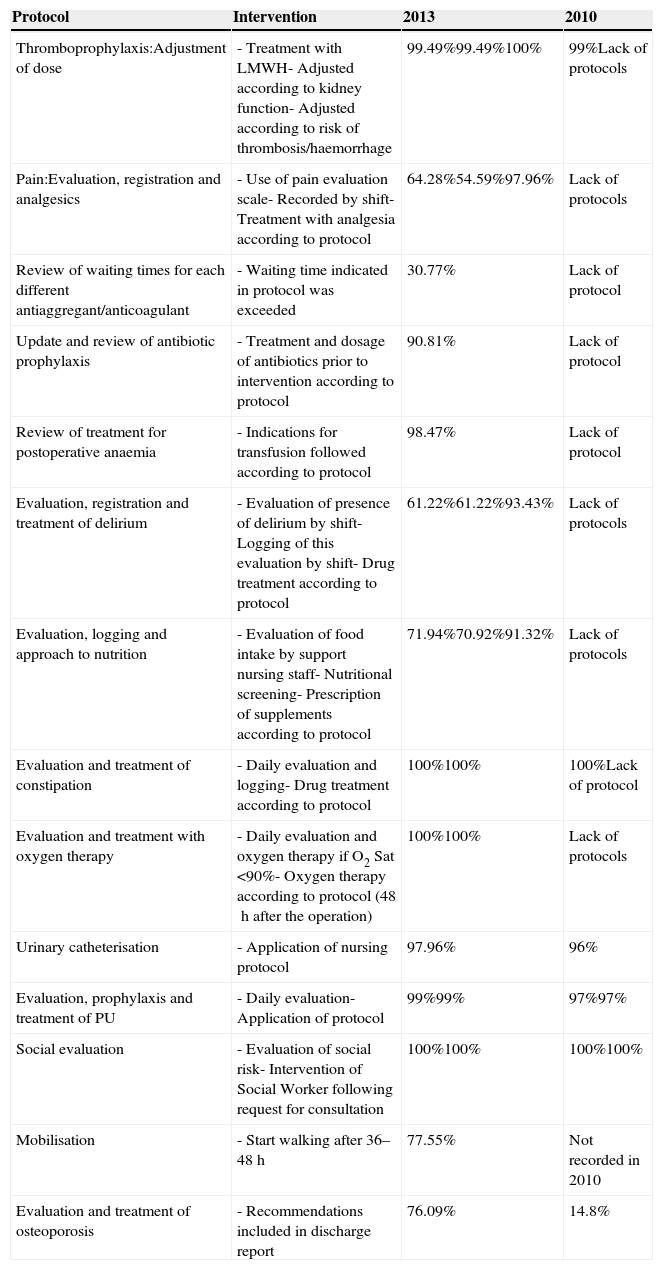

A series of improvements were applied in the form of protocols15 (summarised in Table 5):

- 1.

Thromboprophylaxis: in 2010, the dose of low molecular weight heparin was not individualised. In 2013, the doses were adjusted in patients with kidney failure and in those following anticoagulation therapy with a high risk of thrombosis, in which case heparin administration was suspended 24hours prior to the surgery.

- 2.

Management of patients with antiaggregant/anticoagulant treatment: in 2010 the delay until surgery was up to 7 days with any antiaggregant and vitamin K was not used in anticoagulated patients. In 2013, as part of the clinical pathway, a protocol for the management of these patients based on recommendations by the scientific society, among other sources,16 was jointly elaborated with the Anaesthesiology Service. It was decided that no surgical delay was required in case of acetylsalicylic acid, and that delay should be reduced to 5 days for clopidogrel and 2–3 days for new anticoagulants, depending on kidney function. Vitamin K was employed to reverse the effects of acenocoumarol and reduce surgical delay.

- 3.

Analgesia: in 2013, a protocol was implemented to alternate intravenous metamizole and paracetamol. Subcutaneous morphine chloride or tramadol were administered in case of poor pain control. The effects of the treatment were quantified by means of a descriptive pain scale and recorded by Nursing staff.

- 4.

Antibiotic prophylaxis: in 2010, the duration of antibiotic prophylaxis ranged between 1 and 5 days, depending on the surgeon. In 2013, the criteria were unified and a single intravenous dose of 2g cefazolin prior to the intervention was established, with 1g vancomycin in the case of patients allergic to beta-lactams.

- 5.

Delirium: there was no treatment protocol and its onset was not registered in the 2010 group. In 2013, all patients received multidisciplinary care and an intervention by geriatrics for prevention, treatment of complications and subsequent reduction of the incidence of delirium, as well as drug treatment with risperidone and/or haloperidol. The nursing charts for each shift reflected the presence of delirium, after applying the Confusion Assessment Method as a screening test.

- 6.

Anaemia: in 2013, a transfusion protocol was defined for cases suffering postoperative anaemia. According to this, cases with haemoglobin (Hb)≥10 did not require transfusions, Hb≤8g/dl received transfusion of 2 units of packed red cells, Hb 8–10g/dl received 200mg intravenous iron sucrose 3 times per week (between 600 and 1000mg in total), except for patients suffering heart/respiratory failure or cerebral ischaemia, who received transfusions.

- 7.

Malnutrition: absence of protocols in 2010. In 2013, support staff and/or relatives recorded the intake of each meal in a document placed at the header of the bed. Geriatrics and nursing staff screened for malnutrition using the 2002 Nutritional Risk Score and food supplements were prescribed when necessary.

- 8.

Rehabilitation: if there was no transfusion criterion according to the protocol described previously and the radiographic control conducted on the morning after the intervention was satisfactory, we proceeded to allow sitting up in the first 24h. Standing on two legs was allowed after 36–48h. Walking was authorised in all cases except those suffering extracapsular fracture with an instability pattern.17 Re-training for walking was carried out progressively, according to the tolerance of each patient, with the support of the Rehabilitation Service.

- 9.

Multidisciplinary care: in 2010 geriatricians provided consultation upon request from Orthopaedics on weekdays; the rest of the time, in case of need patients were referred to specialists on call in each situation. In 2013 a more coordinated workflow was organised, with daily joint visits by Orthopaedics, Geriatrics and Nursing staff and shared responsibility for each patient between these professionals from the moment of admission until discharge. Regular formal meetings were held with Anaesthesia, Rehabilitation and Social Work. Social, and anaesthetic risk and rehabilitation potential of all patients were also evaluated.

- 10.

Oxygen therapy: implemented during the first 48h after the intervention and in cases where oxygen saturation was under 90%, according to the 2013 protocol.

- 11.

In 2013, planning of programmed activity was modified, giving priority to surgery of elderly patients with hip fractures and attempting to carry out procedures in the first hours after admission.

- 12.

In 2010, each orthopaedist individually decided whether to treat osteoporosis after a fracture. In 2013, a protocol was elaborated following European consensus18 and SECOT-GEIOS recommendations.19 Like other protocols, it is described in the publication “Treatment strategies for hip fractures in elderly patients”.15 The protocol describes the reposition of vitamin D and calcium supply, the use of each drug and how to select treatments based on comorbidity and the life expectancy of each patient, according to the Nottingham Hip Fracture, Charlson and Parker Mobility scales. Drug treatment for patients with extensive disability or a short life expectancy is less clear, and the best cost-benefit ratio in such cases has been observed with an association of calcium and vitamin D.20 Determination of vitamin D was not carried out systematically; only in patients with suspected deficit due to scarce solar exposure (institutionalised or confined to home).

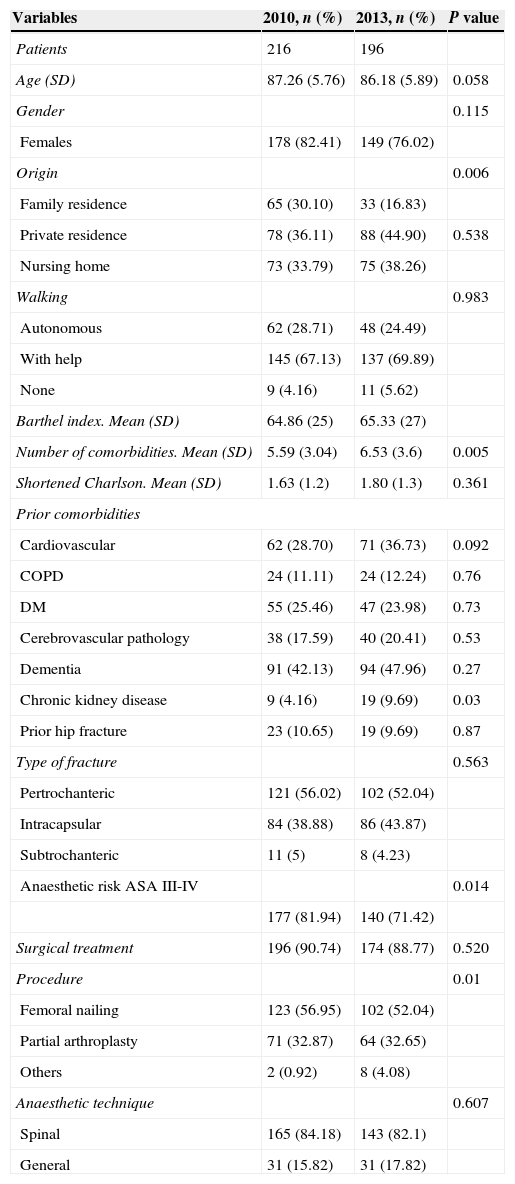

No statistically significant differences were registered between groups in terms of baseline epidemiological characteristics, so it was assumed that both groups were comparable (Table 2).

Baseline epidemiological, medical-surgical and functional characteristics.

| Variables | 2010, n (%) | 2013, n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 216 | 196 | |

| Age (SD) | 87.26 (5.76) | 86.18 (5.89) | 0.058 |

| Gender | 0.115 | ||

| Females | 178 (82.41) | 149 (76.02) | |

| Origin | 0.006 | ||

| Family residence | 65 (30.10) | 33 (16.83) | |

| Private residence | 78 (36.11) | 88 (44.90) | 0.538 |

| Nursing home | 73 (33.79) | 75 (38.26) | |

| Walking | 0.983 | ||

| Autonomous | 62 (28.71) | 48 (24.49) | |

| With help | 145 (67.13) | 137 (69.89) | |

| None | 9 (4.16) | 11 (5.62) | |

| Barthel index. Mean (SD) | 64.86 (25) | 65.33 (27) | |

| Number of comorbidities. Mean (SD) | 5.59 (3.04) | 6.53 (3.6) | 0.005 |

| Shortened Charlson. Mean (SD) | 1.63 (1.2) | 1.80 (1.3) | 0.361 |

| Prior comorbidities | |||

| Cardiovascular | 62 (28.70) | 71 (36.73) | 0.092 |

| COPD | 24 (11.11) | 24 (12.24) | 0.76 |

| DM | 55 (25.46) | 47 (23.98) | 0.73 |

| Cerebrovascular pathology | 38 (17.59) | 40 (20.41) | 0.53 |

| Dementia | 91 (42.13) | 94 (47.96) | 0.27 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (4.16) | 19 (9.69) | 0.03 |

| Prior hip fracture | 23 (10.65) | 19 (9.69) | 0.87 |

| Type of fracture | 0.563 | ||

| Pertrochanteric | 121 (56.02) | 102 (52.04) | |

| Intracapsular | 84 (38.88) | 86 (43.87) | |

| Subtrochanteric | 11 (5) | 8 (4.23) | |

| Anaesthetic risk ASA III-IV | 0.014 | ||

| 177 (81.94) | 140 (71.42) | ||

| Surgical treatment | 196 (90.74) | 174 (88.77) | 0.520 |

| Procedure | 0.01 | ||

| Femoral nailing | 123 (56.95) | 102 (52.04) | |

| Partial arthroplasty | 71 (32.87) | 64 (32.65) | |

| Others | 2 (0.92) | 8 (4.08) | |

| Anaesthetic technique | 0.607 | ||

| Spinal | 165 (84.18) | 143 (82.1) | |

| General | 31 (15.82) | 31 (17.82) | |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; SD, standard deviation.

The number of comorbidities was higher in the 2013 group, with the most frequent overall being dementia, cardiovascular pathology and diabetes mellitus (Table 2). More than half of the cases in both groups were pertrochanteric fractures. In relation to this, femoral nailing was the most common procedure. The majority of patients (>80%) were intervened under spinal anaesthesia (p=0.706).

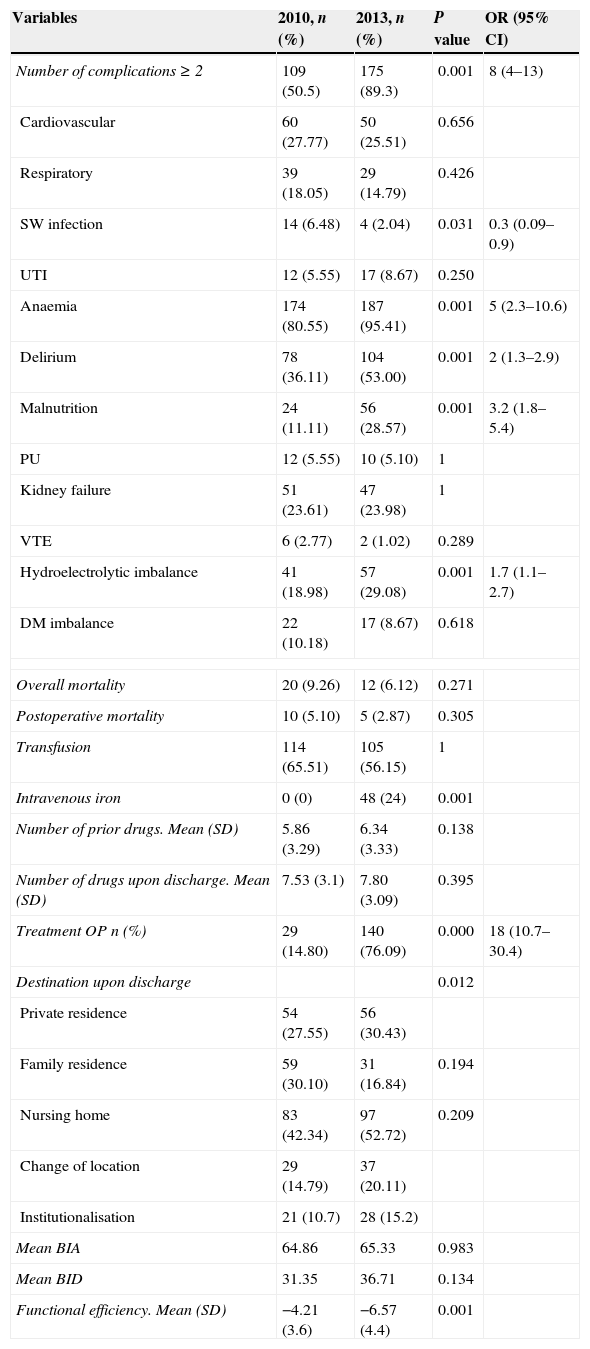

The highest number of complications were detected during admission in the intervention group (p=0.000), with the most frequent diagnoses being anaemia, delirium, malnutrition and electrolyte imbalances (p<0.05). On the other hand, the incidence of surgical wound infection and the need for transfusion were lower in this group (p=0.031).

In-hospital mortality of intervened patients following the procedure was reduced by 2.23% (p=0.305) (Table 3).

Comparison of clinical-therapeutic, functional and healthcare characteristics before and after the implementation of the quality improvement measures.

| Variables | 2010, n (%) | 2013, n (%) | P value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of complications≥2 | 109 (50.5) | 175 (89.3) | 0.001 | 8 (4–13) |

| Cardiovascular | 60 (27.77) | 50 (25.51) | 0.656 | |

| Respiratory | 39 (18.05) | 29 (14.79) | 0.426 | |

| SW infection | 14 (6.48) | 4 (2.04) | 0.031 | 0.3 (0.09–0.9) |

| UTI | 12 (5.55) | 17 (8.67) | 0.250 | |

| Anaemia | 174 (80.55) | 187 (95.41) | 0.001 | 5 (2.3–10.6) |

| Delirium | 78 (36.11) | 104 (53.00) | 0.001 | 2 (1.3–2.9) |

| Malnutrition | 24 (11.11) | 56 (28.57) | 0.001 | 3.2 (1.8–5.4) |

| PU | 12 (5.55) | 10 (5.10) | 1 | |

| Kidney failure | 51 (23.61) | 47 (23.98) | 1 | |

| VTE | 6 (2.77) | 2 (1.02) | 0.289 | |

| Hydroelectrolytic imbalance | 41 (18.98) | 57 (29.08) | 0.001 | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) |

| DM imbalance | 22 (10.18) | 17 (8.67) | 0.618 | |

| Overall mortality | 20 (9.26) | 12 (6.12) | 0.271 | |

| Postoperative mortality | 10 (5.10) | 5 (2.87) | 0.305 | |

| Transfusion | 114 (65.51) | 105 (56.15) | 1 | |

| Intravenous iron | 0 (0) | 48 (24) | 0.001 | |

| Number of prior drugs. Mean (SD) | 5.86 (3.29) | 6.34 (3.33) | 0.138 | |

| Number of drugs upon discharge. Mean (SD) | 7.53 (3.1) | 7.80 (3.09) | 0.395 | |

| Treatment OP n (%) | 29 (14.80) | 140 (76.09) | 0.000 | 18 (10.7–30.4) |

| Destination upon discharge | 0.012 | |||

| Private residence | 54 (27.55) | 56 (30.43) | ||

| Family residence | 59 (30.10) | 31 (16.84) | 0.194 | |

| Nursing home | 83 (42.34) | 97 (52.72) | 0.209 | |

| Change of location | 29 (14.79) | 37 (20.11) | ||

| Institutionalisation | 21 (10.7) | 28 (15.2) | ||

| Mean BIA | 64.86 | 65.33 | 0.983 | |

| Mean BID | 31.35 | 36.71 | 0.134 | |

| Functional efficiency. Mean (SD) | −4.21 (3.6) | −6.57 (4.4) | 0.001 | |

95 CI, 95% confidence interval; BIA, Barthel index upon admission; BID, Barthel index upon discharge; DM, diabetes mellitus; OR, odds ratio; PU, pressure ulcer; SD, standard deviation; SW infection, surgical wound infection; Treatment OP, treatment for osteoporosis; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

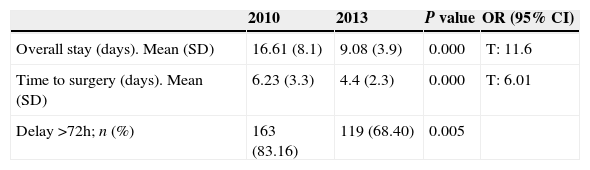

The mean overall stay showed a significant year-on-year decrease of 7.53 days (from 16.61 days in 2010 to 9.08 days in 2013; p=0.000) and time to surgery showed a decrease of 1.83 days (from 6.23 to 4.4 days; p=0.000). The percentage of patients intervened more than 72h after admission went down by nearly 15% between 2010 and 2013 (p=0.000) (Table 4). It is worth highlighting the reduction in surgical delay secondary to treatment with platelet antiaggregants after the implementation of the clinical pathway (p=0.000).

Bivariate analysis of stay and time until surgery. Comparison between groups.

| 2010 | 2013 | P value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall stay (days). Mean (SD) | 16.61 (8.1) | 9.08 (3.9) | 0.000 | T: 11.6 |

| Time to surgery (days). Mean (SD) | 6.23 (3.3) | 4.4 (2.3) | 0.000 | T: 6.01 |

| Delay >72h; n (%) | 163 (83.16) | 119 (68.40) | 0.005 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

No differences in the Barthel index were registered between groups upon discharge. Nevertheless, functional efficiency (including the stay variable) presented favourable results in the 2013 group of patients (p=0.000).

In the intervention group, the number of patients receiving drug treatment for osteoporosis was multiplied by five (p=0.000).

The highest percentage of patients who were transferred to nursing homes, changed location and were institutionalised for the first time (Table 3) was observed in 2013.

The level of compliance with the protocol was above 90% for most of the indicators (Table 5).

Description of the protocols implemented and distribution of the level of compliance in 2013.

| Protocol | Intervention | 2013 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thromboprophylaxis:Adjustment of dose | - Treatment with LMWH- Adjusted according to kidney function- Adjusted according to risk of thrombosis/haemorrhage | 99.49%99.49%100% | 99%Lack of protocols |

| Pain:Evaluation, registration and analgesics | - Use of pain evaluation scale- Recorded by shift- Treatment with analgesia according to protocol | 64.28%54.59%97.96% | Lack of protocols |

| Review of waiting times for each different antiaggregant/anticoagulant | - Waiting time indicated in protocol was exceeded | 30.77% | Lack of protocol |

| Update and review of antibiotic prophylaxis | - Treatment and dosage of antibiotics prior to intervention according to protocol | 90.81% | Lack of protocol |

| Review of treatment for postoperative anaemia | - Indications for transfusion followed according to protocol | 98.47% | Lack of protocol |

| Evaluation, registration and treatment of delirium | - Evaluation of presence of delirium by shift- Logging of this evaluation by shift- Drug treatment according to protocol | 61.22%61.22%93.43% | Lack of protocols |

| Evaluation, logging and approach to nutrition | - Evaluation of food intake by support nursing staff- Nutritional screening- Prescription of supplements according to protocol | 71.94%70.92%91.32% | Lack of protocols |

| Evaluation and treatment of constipation | - Daily evaluation and logging- Drug treatment according to protocol | 100%100% | 100%Lack of protocol |

| Evaluation and treatment with oxygen therapy | - Daily evaluation and oxygen therapy if O2 Sat <90%- Oxygen therapy according to protocol (48h after the operation) | 100%100% | Lack of protocols |

| Urinary catheterisation | - Application of nursing protocol | 97.96% | 96% |

| Evaluation, prophylaxis and treatment of PU | - Daily evaluation- Application of protocol | 99%99% | 97%97% |

| Social evaluation | - Evaluation of social risk- Intervention of Social Worker following request for consultation | 100%100% | 100%100% |

| Mobilisation | - Start walking after 36–48h | 77.55% | Not recorded in 2010 |

| Evaluation and treatment of osteoporosis | - Recommendations included in discharge report | 76.09% | 14.8% |

LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; PU, pressure ulcer.

The bivariate analysis of all patients (412) found that a surgical delay above 72h was associated with a longer overall stay (p=0.000), a higher number of complications during hospitalisation (p=0.022) and greater use of drugs upon discharge (p=0.023). Likewise, a relationship was found between the number of complications and advanced age (over 85 years), high comorbidity (Charlson index over 3 and more than 5 comorbidities), including dementia, level of dependence upon admission (Barthel index at admission <60 points), ASA≥III and surgical delay over 72h (P<0.005). In-hospital mortality was influenced by age over 85 years, polypharmacy and prior functional impairment (Barthel index at admission <60 points).

DiscussionImplementation of a clinical pathway in any process improves and updates the clinical practice of professionals, making it more uniform. This work, which describes details of the clinical pathway employed, found differences in both clinical and management data regarding different aspects, as commented below.

Overall stayOverall stay is a frequently studied variable. It can refer to the acute phase, as in the case of this work, or else include the subacute period, which encompasses stay at centres for functional recovery.

The hospitalisation period in patients with HF has decreased progressively since the late 1990s, and currently has a mean duration of 13.34 days,21 with considerable differences not only throughout the period analysed, but also between political regions. A recent work conducted in Castilla y León22 to evaluate orthogeriatric activity in this political region registered a mean hospital stay of 10 days (range: 8–13 days). These figures are below those reported in recent national publications, with periods ranging between 10 and 19 days.3,6,21,23 The values obtained in Ávila H.C. showed a decrease of 45.3% in hospital stay following implementation of the improvement plan (p=0.000). The intervention group presented a lower overall stay than the national and regional averages, as well as the control group. Thus a positive relationship was established due to the multidisciplinary and protocol-based management implemented.

Hospital stay at a ward represented the main fraction of the costs of the acute phase of the hip fracture process.23 Based on this information, it could be deduced that the best way to reduce expenses in the acute phase would involve shortening the time of admission in this acute phase. However, it is also known that reducing this phase excessively will have a negative repercussion on the short and long term functional results, with a higher rate of transfers to nursing homes and subsequent increase of expenses and movement between centres.24 Therefore, the aim should be to reinforce the concept of efficient stays,23 defined as those achieving the best clinical and functional results in the shortest possible time, with the ideal goal of reducing waiting time until surgery. This was the objective pursued and achieved through the implementation of the clinical pathway in 2013. A clinical pathway can be considered efficient because it produces economic savings through a reduction in consumption of resources. The mean daily cost of a hospital bed in Orthopaedics at our centre is estimated at 177.55 €. Considering that, in 2013, hospital stays were reduced by 7.5 days, we can calculate approximate savings of 1335.2 € per patient. Since the results from the clinical standpoint also improved, we can consider that the tool applied was not only effective, but also efficient (the same clinical and functional result was achieved in less time).

Time to surgeryThe objectives in multidisciplinary management of elderly patients with hip fracture include the aim of applying the necessary measures to achieve early surgical treatment.6

Therefore, part of the objective of this research was to evaluate the influence on time until surgery of the improvement plan implemented. A decrease of 29.4% was observed (from 6.23 to 4.40 days, P=0.000), which contributed to a shorter total stay, among other factors.

At a national level, the figures are around 4.31 days,21 whilst in the region of Castilla y León the delay is of 3 days.22

The medical literature does not go into detail about the definition of urgent or early surgery in hip fractures. Whilst some works25,26 consider the optimum time to surgery to be 24–48h or less, others reduce this delay period to 12h or increase it beyond 72h.25,26 Some authors highlight the importance of improving systems that would enable identification of patients who would truly benefit from early surgery, rather than determining the effect of an early intervention on all patients indiscriminately.27,28 In this regard, patients with the highest risk of developing complications and dying during admission were the oldest, those associating highest levels of comorbidities (among them, dementia), those with the highest levels of dependence, patients under polypharmacy, ASA ≥III and surgical delay over 72h (in the latter case with no relationship to mortality). It is on this latter group patients that we should focus our efforts to provide early surgery.

Regarding the causes of surgical delay, according to the Orosz criteria,29 both groups showed a predominance of unavailability of operating rooms, followed by admission on a holiday and treatment with platelet antiaggregants. Implementation of the clinical pathway, modification of the surgical programming, awareness by all staff about the importance of early surgery and review of the waiting times for antiaggregants/anticoagulants managed to reduce surgical delay by almost two days.

There is currently no consensus in the literature regarding the most adequate anaesthetic technique for elderly patients with hip fractures.30 Nevertheless, there is a preference for regional anaesthesia whenever possible, as it has demonstrated greater benefits than general anaesthesia, particularly in ASA III and IV patients.31,32 Evaluating the risk/benefit entails selecting the moment with the minimum necessary surgical delay which still allows the benefits of regional anaesthesia to be maintained without increasing the risk of haemorrhage and thrombosis. For these reasons, most professionals lean towards regional anaesthesia in geriatric patients,33 despite being contraindicated with certain antiaggregants.16 Both facts, deferred emergency and preference for regional anaesthesia, entail a delay, until the effect of antiaggregant and antithrombotic drugs ceases to represent an unacceptable risk of bleeding. In this respect, some works have reported that short patterns of antiaggregant suspension are not associated to greater intraoperative bleeding,34 whilst others have reported an increase in the proportion of transfusion,35,36 as well as the incidence of thrombotic episodes.37

Neither is there a consensus about the waiting period for each antiaggregant.36 In fact, this is highly variable, depending on hospitals and professionals. Considering that 17.4% of the overall sample was following anticoagulant treatment and 18.9% antiaggregant treatment, the protocol elaborated jointly with the Anaesthesiology Service and the recommendations of that scientific society have managed to reduce surgical delay without increasing the rate of complications.

We know that the main clinical practice guidelines establish a surgical delay of 24h or less.10–13 This figure is far from our results, despite having improved following the implementation of the clinical pathway and registering a 29.37% reduction in time to surgery compared to the control group. However, we still suffered from the same key drawback reported by all publications evaluating this factor as the most frequent cause of surgical delay regardless of the characteristics of each centre: organisational reasons and lack of available operating rooms.25,27,28

Attempting to reduce time to surgery represents our greatest challenge. During the study period, the Orthopaedics Service of the Ávila Complejo Asistencial was assigned 32 of the total 350 beds available. It only had use of 1 operating room per day in the mornings and, exceptionally, some afternoons, for both elective surgery and orthopaedics, so the percentage of cases with delayed surgery for this reason is not surprising. Emergency surgery is often ruled out due to multiple accompanying pathologies, and the most common approach is to wait until patients become stable.28 On the other hand, there is currently an effort underway to systematically “reserve” the first hour of the emergency operating room for patients with hip fractures, and follow the agreed protocols in the case of patients with antiaggregation/anticoagulation treatment.

Consequences of surgical delayThere is no consensus about considering time to surgery as a measurement of the level of efficiency in the management of patients admitted due to hip fracture, given the poor results and the existing variability.27 The present study registered a relationship between surgical delay over 72h and a greater number of complications, drug use upon discharge and hospital stay, but not with mortality. There is a discrepancy in the literature regarding the association between these variables and, in fact, although some authors do not establish a link between time to surgery and mortality at 1 year,27,28,38–40 they do recommend early surgery in order to avoid medical complications and improve patient comfort, considering it reasonable to postpone the intervention until any comorbidities have become stabilised.27,28,38–40

MortalityIn Spain, in-hospital mortality among elderly patients with hip fractures is around 5%.21 After implementing quality improvement measures, in-hospital mortality was reduced by 44% among operated patients, albeit with no statistical significance, probably due to having an insufficient number of cases. Factors like the inclusion of younger patients, exclusion of patients with dementia and short hospital stays contribute to low mortality figures in some studies.6,26,41 In our work, despite having elderly patients with a high prevalence of dementia and comorbidities, in-hospital mortality was comparable to that reported by other authors.24,41

ComorbidityPatients in both groups presented mean values for age, comorbidities (specifically dementia and cardiovascular pathology) and polypharmacy (60–70%) above the majority of national series reviewed,6,7,42 probably linked to the high rate of ageing in the province, which has 25% of inhabitants aged over 65 years.

Between 15% and 30% of patients with hip fractures presented severe complications during the acute phase, with considerable variability in terms of frequency being observed between authors.43 A higher number of complications was registered in the intervention group compared to the control group. In spite of this, hospital stay was reduced. Implementation of the clinical pathway led to a review and update of the management of thromboprophylaxis, antiaggregation/anticoagulation, analgesia, antibiotic prophylaxis, delirium, anaemia, nutrition, osteoporosis and rehabilitation. The fact that healthcare staff was trained in prevention and approach of these problems facilitated their detection among the intervention group, which may have led to an observation bias. On the other hand, the statistical association observed between a higher number of complications and advanced age, greater comorbidities, surgical risk (ASA≥III), higher level of prior dependence and surgical delay was coherent with the results reported by other studies.28,44 Thus, although the 2013 group apparently had more complications, it did not present a worse functional condition upon discharge, longer hospital stay or higher mortality, which confirms the objective of efficient hospital stay.

Orthogeriatric collaborationCompared to traditional management, orthogeriatric collaboration, be it through a consultation model or as an orthogeriatrics unit, registers better results in terms of time to surgery,7,8,40,45 overall hospital stay,7,8,40,43,46 detection of complications,8,9,45 lower rates of readmission and disability,9,45,47 in-hospital and long-term mortality,7 along with a reduction in healthcare costs.3,47 In addition, regarding more classical models, the comprehensive approach focuses on secondary prevention of fractures, increasing the number of patients discharged with a prescription for calcium/vitamin D (67% vs. 2% in the basic models) and antiresorptive treatment (10% vs. 1%).24,48 All these results are in line with those obtained during the present research.

However, it is true that orthogeriatric collaboration does not always manage to reduce hospital stay.48,49

In 2013, nearly 6% more patients changed their location upon discharge than in the control group. This change translated into more transfers of patients to nursing homes, probably due to modern family structures, with less support for dependent elderly individuals. The absence of Functional Recovery Units as a specific geriatric resource in our province meant that, upon discharge, the only options available were to return home or to a residence for the elderly.50 Often, one of the reasons for reducing hospital stay was the possibility of referral to Functional Recovery Units,51 whilst in other cases their absence after the acute phase prevented patients from being discharged.52 Nevertheless, in our experience, the length of overall stay was reduced among the intervention group, without having that healthcare level.

BiasIn addition to the possible observational bias mentioned previously, the limitations of this work include a difficulty in applying the clinical pathway at other centres, due to the specific characteristics of each hospital. On the other hand, its advantages include an update on clinical problems by the researchers themselves, as well as the group of collaborators, leading to a consensus to improve patient care. The updated knowledge of multidisciplinary management of several problems present in these patients facilitated the application of individualised protocols at each centre, thus improving the quality of care.

ConclusionsThe complexity of these patients and the multiplicity of factors affecting their recovery justified the creation of functional interdisciplinary groups at healthcare centres, in order to offer patients a better quality of care and greater life expectancy following a fracture, decreasing medical complications and the length of hospital stay.

The implementation of a clinical pathway at a second level hospital favours the multidisciplinary management of geriatric patients suffering hip fractures due to fragility. In addition, it contributed to update and unify criteria, and to improve the quality of care for these patients.

Among the benefits obtained, it is worth highlighting a shorter time until surgery and overall stay, with no negative repercussions at a clinical or functional level or on survival. Improved detection of complications enabled earlier treatment, avoiding the known cascade of complications, which entail worse clinical and functional evolution, as well as greater mortality. Therefore, the implementation of a clinical pathway of these characteristics was not only effective, but also efficient from the standpoint of use of available resources.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors wish to thank the nursing staff at the Orthopaedics Unit of the Ávila Complejo Asistencial for their collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Hernández N, Sáez-López P, Paniagua-Tejo S, Valverde-García JA. Resultados tras la aplicación de una vía clínica en el proceso de atención al paciente geriátrico con fractura de cadera osteoporótica en un hospital de segundo nivel. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;60:1–11.