To evaluate benefits for the patient and the economic impact for the implementation of a wide awake local anesthesia no tourniquet (WALANT) hand surgery compared to traditional major outpatient circuit.

MethodsA prospective cohort study was planned comparing 150 cases of ambulatory hand surgery (carpal tunnel and trigger finger) using WALANT technique intervention out from the operating room; with another 150 which underwent intervention, outpatient setting, with preoperative evaluation, sedation and tourniquet, in the operation room (OR). Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative pain was monitored, as well as the use of analgesics after the surgery. The resources used and costs were evaluated. Satisfaction was evaluated using a specific survey.

ResultsThe pain during the surgery was equivalent for both groups and was significantly lower postoperatively for the WALANT group, with less need for the use of analgesics. Satisfaction was greater for the local anesthesia group. The use of personnel resources and hospital material was less for the WALANT group, with total saving calculated by 1,019€ per patient.

SummaryProcedures such as carpal tunnel surgery and trigger finger surgery can be safely performed using wide awake surgery. Patient satisfaction is higher to conventional procedure in the OR. Pain control is excellent, especially during the postoperative period. WALANT technique for hand surgery represents a benefit for the patient in comfort, timeliness and no need for a preoperative evaluation or blood test. In addition, it represents a significant savings in hospital resources.

Evaluar los beneficios para el paciente y económicos de la implantación de un circuito de cirugía con anestesia local sin manguito ni sedación (WALANT por sus siglas en inglés) versus pacientes intervenidos en quirófano en cirugía mayor ambulatoria.

MétodoSe diseñó un estudio de cohortes prospectivo comparando 150 casos intervenidos (túneles carpianos y dedo en resorte) de forma ambulatoria mediante técnica WALANT con otros 150 pacientes operados en circuito de cirugía mayor ambulatoria (CMA) con anestesia regional y torniquete, en quirófano convencional. El dolor pre, intra y postoperatorio fue monitorizado, así como los días que precisaron de analgesia postoperatoria. Se evaluaron los costos y recursos utilizados. El grado de satisfacción del paciente fue evaluado mediante un formulario específico.

ResultadosEl dolor intraoperatorio fue similar en ambos grupos, hallando diferencias significativas en cuento a la necesidad de analgesia postoperatoria a favor del grupo WALANT. El grado de satisfacción fue mayor para el grupo de anestesia local. La utilización de recursos materiales y de personal fue menor en WALANT, calculando un ahorro por paciente fue de 1,019 €.

ConclusionesCirugías como el túnel carpiano y el dedo en resorte pueden llevarse a cabo de forma segura mediante la técnica WALANT. La satisfacción del paciente es mayor que la de los pacientes intervenidos en el quirófano. El control del dolor es excelente, especialmente durante el postoperatorio. La técnica WALANT reporta un beneficio para el paciente en términos de confort y rapidez, además de permitir prescindir de pruebas y visita preoperatorias. Su implantación supone un ahorro significativo de recursos hospitalarios.

Orthopaedic surgery is increasingly performed as major outpatient surgery (MOS), i.e., without admission following surgery. The aims are, in addition to cost and time savings, to provide safe and effective care in a facility specifically built for this purpose, maintaining high levels of patient satisfaction through streamlined and effective surgical care. Surgery under local anaesthetic without sedation or cuff, or the wide awake local anaesthesia no tourniquet (WALANT) technique, is a further step in this trend, taking some of the most common hand surgery procedures, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, trigger finger, tendon suture, etc, to a fully outpatient setting outside the MOS circuits. Several authors have studied how to reduce surgical time to increase their turnover.1–4 However, reducing non-surgical time, defined as the time from completion of one surgery to the time of starting the next, is a key objective in enhancing the efficiency of operating theatres.5–9 In Canada, more than 80% of carpal tunnel surgery is performed outside the operating theatre using this method.9–11 Published series indicate high patient satisfaction with no increase in complications.

With the growing popularity of local anaesthesia without sedation, the hand surgeon has a variety of anaesthesia options available to him or her. Local anaesthesia does not require supervision by anaesthetic staff and does not affect induction or recovery times if anaesthesia is given in a preoperative area. General anaesthesia provides the patient maximum anaesthesia, but carries not insignificant risks, requires monitoring by anaesthetic staff, affects induction times and requires the transfer and registration of the patient to a recovery room, all of which increase non-surgical time. Regional anaesthesia combined with sedation can be satisfactory for patients who cannot tolerate local anaesthesia while avoiding many of the risks inherent to intubation and paralysis; however it still requires the presence of an anaesthetist and affects induction and recovery times, which increase non-surgical time.

The basis of the WALANT anaesthetic technique is that it only requires the administration of lidocaine and adrenaline, which avoids the need for sedation and ischaemia cuff, avoiding discomfort and complications for the patient.11–13 The use of anaesthetic with adrenaline, traditionally proscribed in hand surgery, has proven safe in many studies establishing the appropriate dose for each procedure.14–16

Another advantage of this technique is that the preoperative study can be dispensed with, which in our hospital would include chest x-ray, consultation with the anaesthetist and blood tests. The latter is also unnecessary in anticoagulated patients. All of which results not only in cost savings but also savings in time for the institution as well as the patient. The combination with adrenaline multiplies the anaesthetic effect time (up to ten hours), which has been shown to provide better postoperative pain control. It is also a safer anaesthetic technique than general anaesthesia for patients with comorbidities such as kidney failure, morbid obesity and lung problems.17–19 Studies have been examined and published on the economic impact in the health organisations that implement this system, which demonstrate economic benefits due to lower use of hospital resources.20 Simple operations can be performed using the WALANT technique, such as carpal tunnel, trigger finger or De Quervain’s disease procedures, as well as more complex surgeries such as tendon suture and transfer, arthroscopies or trapezium removal for the treatment of rhizarthrosis of the thumb, using dilutions and adequate volume in each case.21

In our department, until 2014 all hand surgery was performed in the operating theatre, after a preoperative procedure, with regional anaesthesia (brachial plexus), sedation and ischaemia cuff. We later proposed a study to assess the implementation in our centre of a circuit with local anaesthesia without sedation for two operations that are routine in upper extremity operating theatres: carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and trigger finger. CTS is caused by compression of the median nerve and is one of the most common peripheral nerve compression neuropathies. Its estimated incidence is between .1% and 10%. Trigger finger is an inflammatory process that involves the flexor sheath of the fingers. Its prevalence ranges from 1%–2.2% in healthy people over the age of 30, and 11% in diabetic patients, with an annual incidence of up to 12.4% in certain manual professions.22–25

The hypothesis of our study is that the anaesthetic technique using local anaesthesia, without cuff and without sedation is just as safe as surgery under regional plexus anaesthesia and more efficient in the use of resources. Therefore, the objective was to assess the benefits for the patient and the economic benefits of implementing a surgery circuit with local anaesthesia without cuff or sedation versus patients operated in the operating theatre in major outpatient surgery.

Material and methodStudy designAfter obtaining the Certificate of Approval from the Research Committee of the Son Llàtzer Hospital, a study was designed to compare the results of the same surgery performed using two different anaesthetic techniques. One group underwent anaesthesia using the WALANT technique in the surgery and the other group under regional anaesthesia with brachial plexus block in a conventional operating theatre.

Three hundred patients diagnosed with CTS and trigger finger were operated consecutively by hand surgeons with a similar level of experience between June 2014 and December 2016. The choice between the WALANT circuit and the conventional circuit was made according to the surgeon’s preference. Eventually two groups of 150 patients were obtained. Both groups had similar baseline characteristics (demographics, age, sex, affected side). All the patients were duly informed about the study and signed the informed consent form. Surgery was indicated after failure of conservative treatment (anti-inflammatory plus night splints for patients with CTS and corticosteroid injections for those with TF). The inclusion criteria were clinical and exploration compatible with trigger finger and/or CTS, for the latter adding an electromyogram compatible with moderate or acute CTS. Only patients who refused to participate in the study were excluded. No patients were excluded due to previous surgeries, associated comorbidities or treatment with anticoagulants or antiaggregants, and in no case were these drugs discontinued.18 The surgical technique used was identical in both groups. The postoperative analgesic regimen was identical in both groups, first-line analgesia (first rung of the WHO analgesic ladder).

Circuits- a)

Surgery under local anaesthesia and adrenaline, without tourniquet (WALANT) in the small operating room.

After being visited by the surgeon the patient is given an appointment for the intervention. There is no preoperative procedure or anaesthetic assessment in any case. On the day of surgery, the patient goes to a small operating room in the hospital’s outpatient surgery, with standard surgical asepsis conditions, and an assistant and nurse. No cases have venoclysis. In an adjacent room the surgeon administers a combination of 1% lidocaine with 1/100,000 adrenaline according to the dose and technique as described by Lalonde: 20 cc subcutaneously for carpal tunnel (10cc proximally and 10cc in palmar incision) and 4 cc for trigger finger, 27 or 30G needles are used interchangeably for this. In all cases, bicarbonate (1mole) in a ratio of 1/10 is added. The patient goes through to the small operating room, where a sterile field is prepared and they are monitored by pulse oximeter and blood pressure measurement. The recommended time between injection and surgery is 15–20min; this time is used to anaesthetise the next patient. The patient is discharged immediately following the surgery.

- •

Surgery under plexus block, in conventional operating theatre (MOS) with tourniquet:

After surgery is indicated, the patient is assessed in the anaesthetic outpatient clinic, with a full preoperative procedure, which in our hospital includes blood tests, electrocardiogram and chest X-ray. The day of the intervention the patient is admitted to the major outpatient surgery area where they are assigned a bed. The nurse undertakes the standard protocols which include placement of a venous line. The patient is then transferred by a hospital porter to the operating theatre, where they are received by the anaesthetist who performs the axillary block. The operating theatre has two nurses and an assistant. The operation is also performed with sedation (not deep) and tourniquet in all cases. After the surgery, the patient is transferred back to the COT, from which they are discharged a few hours later.

Post-operative monitoring and assessment of resultsPost-operative clinical monitoring of both groups was undertaken in outpatient clinics at 24h to assess the state of the wound and at one month to assess the results using a questionnaire. This form was provided by the clinic assistant. Tolerance to the two anaesthetic techniques was assessed based on patient-related factors.

PainWe assessed pre-, intra- and postoperative pain. “Preoperative” relates to puncture for the axillary plexus block and venous cannulation in the MOS group and to the administration of local anaesthetic in the WALANT group. “Intraoperative pain” was defined as pain perceived by the patient during surgery in both groups and from the ischaemia cuff (in the regional anaesthesia group).

Pain was assessed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the need for postoperative analgesia (days). The same survey asked about the overall pain of the experience compared with a visit to the dentist (more painful/equal/less painful).

AnxietyThe patient’s level of anxiety in the three phases of the procedure was subjectively assessed using a visual analogue scale from 0 (no anxiety or low satisfaction) to 10 (extreme anxiety or high satisfaction).

Monitoring of the woundThe presence of complications was assessed (at 24h and at one month after surgery), understanding haemorrhage, infection, suture dehiscence or skin necrosis as complications.26 The latter was particularly watched because in previous decades adrenaline was believed to cause necrosis if injected into the hands or fingers.

Patient satisfactionThe patients rated the circuit that they experienced (preoperative tests, waiting time to surgery, length of hospital stay, pain and postoperative period) by visual analogue scale (not validated) from 0 (low satisfaction) to 10 (high satisfaction).27 The patient recorded this in the survey that they completed at the check-up one month following the surgery. We also assessed the level of adherence to treatment: we asked the patients whether they would repeat the experience and how they would prefer to repeat it, three options were attached: 1) awake, with local anaesthesia 2) sedated, with local anaesthesia 3) completely asleep.

ManagementIn relation to the factors relating to management, consumption of hospital resources (operating theatres occupied/freed, staff required) and savings were gathered according to the latest scale published in the Official Gazette of the Autonomous Community where the study was undertaken.

StatisticsThe distribution of the variables was studied with graphs and a test of normality. The quantitative variables were expressed as medians (Q1-Q3) and the qualitative variables as frequencies (percentage). The statistical tests used to compare variables between groups were the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. A statistically significant level of significance was considered to be p<.05. IBM SPSS was used for the statistical analysis.

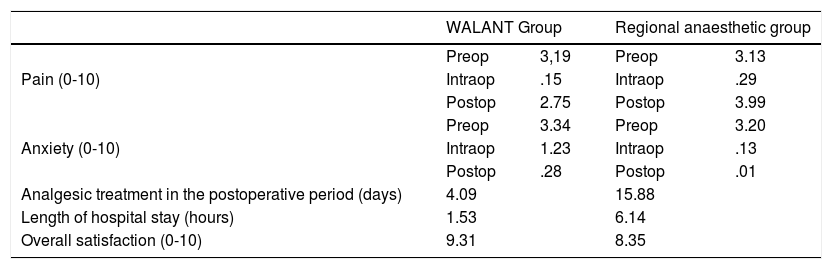

ResultsThere was no loss to follow-up in either group. All the patients in both groups attended the established check-ups and completed the questionnaire (Table 1).

Table of results.

| WALANT Group | Regional anaesthetic group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain (0-10) | Preop | 3,19 | Preop | 3.13 |

| Intraop | .15 | Intraop | .29 | |

| Postop | 2.75 | Postop | 3.99 | |

| Anxiety (0-10) | Preop | 3.34 | Preop | 3.20 |

| Intraop | 1.23 | Intraop | .13 | |

| Postop | .28 | Postop | .01 | |

| Analgesic treatment in the postoperative period (days) | 4.09 | 15.88 | ||

| Length of hospital stay (hours) | 1.53 | 6.14 | ||

| Overall satisfaction (0-10) | 9.31 | 8.35 | ||

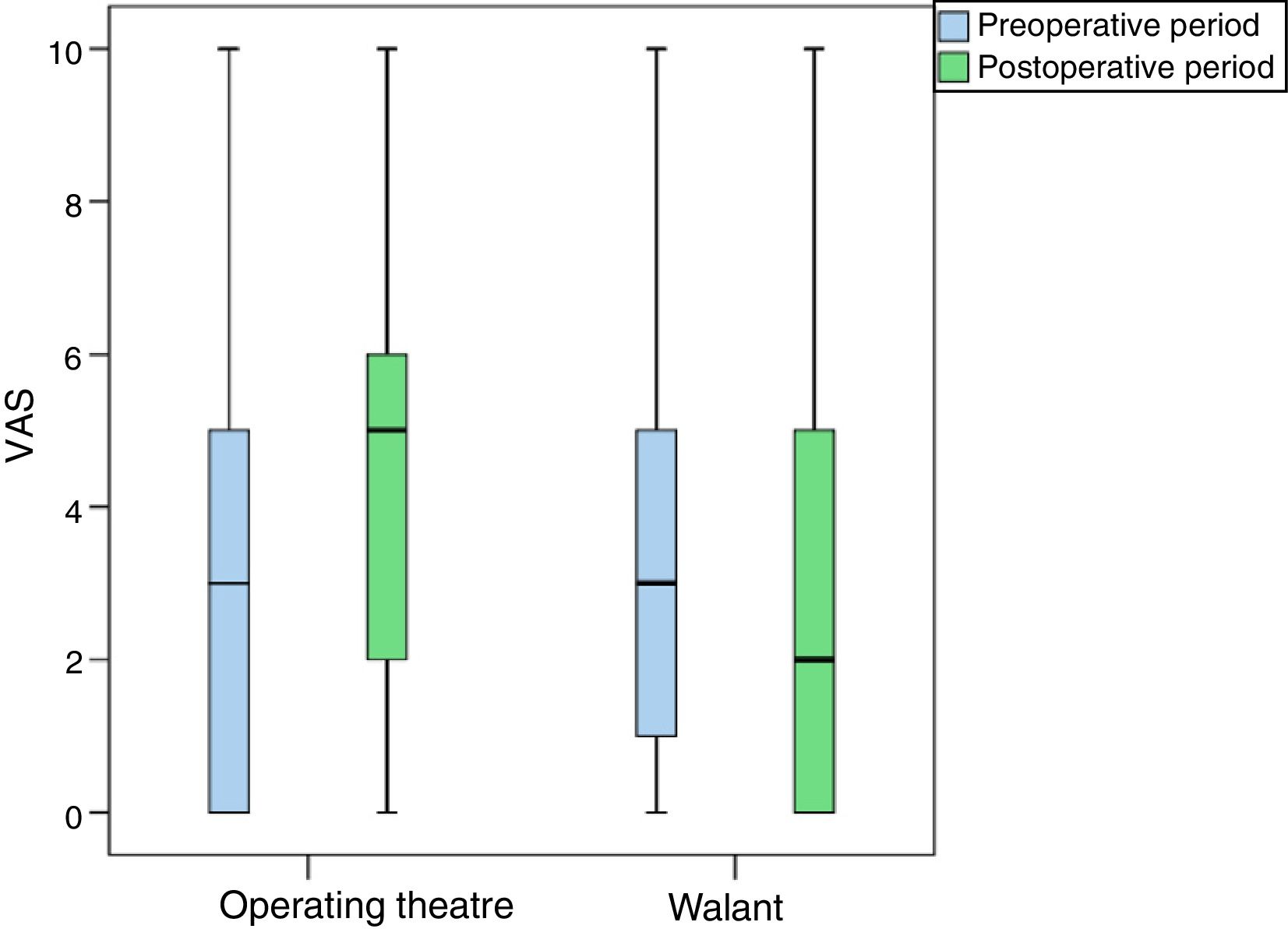

In our study no statistically significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of preoperative pain. The patients operated in the operating theatre had a VAS 3 (0–5) and those operated in the small operating room had a VAS 3 (1–5) (p=.723).

No intraoperative differences were found either, the pain with local anaesthesia was similar to that of the sedated patients and those with ischaemia cuff in the operating theatre; both near zero (.15 vs. .29; p=.601; Fig. 1).

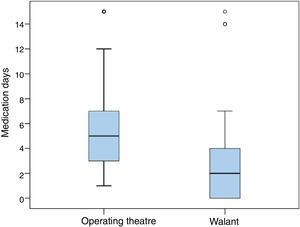

However, statistically significant differences were found in the need for postoperative analgesia, which was 2 days (0–3) in the case of WALANT surgery, compared to 5 days (3–7) for surgery in the operating theatre (p<.001).

For most of the patients the experience in both procedures was better than that of a dental procedure, both in the small operating room (83%) and in the operating theatre (78%) (Fig. 2).

Anxiety. Nausea and vomitingAlthough there were no statistically significant differences in terms of intraoperative anxiety, the patients operated in the operating theatre under sedation had less anxiety (3.34 vs. 3.20; p=.805).

In the postoperative period, none of the patients operated in the small operating room had nausea or vomiting, while 3.3% of the patients operated in the operating theatre did have nausea or vomiting.

Monitoring of the woundThis was undertaken at 24h and at one month in treatment rooms by staff of the Traumatology Unit of our hospital.

The dilution of lidocaine and adrenaline 1/100,000 proved safe in our series. No cases of skin necrosis or increased surgical wound problems, such as infection or skin dehiscence, were found with respect to surgery under regional anaesthetic.15

The patients taking anticoagulant treatment had no postoperative complications of any type.19

Patient satisfaction26Satisfaction was very high for both procedures, 9.31 for WALANT and 8.35 for the operating theatre, and was statistically significant in favour of WALANT (p=.13).

Adherence for the small operating room procedure was high, up to 95% would choose it again.

It should be noted that up to 24% of patients operated in the operating theatre would choose a more simple, outpatient procedure such as that offered by the WALANT technique. In other words, up to a quarter of the patients in the operating theatre group would prefer a simpler, shorter-stay procedure, while almost all the patients operated with WALANT in the small operating room would repeat the same procedure.

Length of hospital stayThe time spent in hospital, understood as the time from the patient’s admission to hospital to their discharge, was significantly lower, 1h (1–2), in the small operating room group compared to the operating theatre group, 6h (4–7).

Resources usedThe patients operated in the small operating room using the WALANT anaesthetic technique did not require a preoperative visit with the anaesthetist, and therefore they did not require an electrocardiogram, chest x-ray or preoperative blood tests, tests that all patients to be operated in theatre undergo in our hospital, regardless of their disease or comorbidities. A cost saving of 16.88€ per patient was achieved with this, and they did not use the MOS area (329.86€). The cost of surgery in the small operating room is less, principally due to the few human resources used, reaching a cost of € 393. Each patient operated in a conventional operating theatre, with an anaesthetist, nurses, assistant and surgeons cost of € 1,412, including their passage through the MOS.

DiscussionThe combination of lidocaine with adrenaline and its use in more common hand surgery procedures has gained in popularity in recent years since its popularisation for flexor repair, and its use has been extended to many operations of increasing complexity.9,10,28,29 Its safety has been demonstrated in several articles, such as that by Lalonde et al. in 2005 with a series of more than 3000 patients.14 The cases of skin necrosis published before 1950 related to the acidity of procaine.15 This does not occur with lidocaine, of proven safety and used daily by dentists worldwide. At the recommended doses for hand surgery no general effect of the anaesthetic has been reported. Nevertheless, dilution is recommended when undertaking more complex surgical procedures that require a more extensive anaesthetic area.16 With regard to adrenaline, there are no known effects of sustained ischaemia, even in the case of doses one hundred times higher than those used in wide awake surgery (WAS) injected accidentally.30 And if this should occur, its effect can be reversed by the use of phentolamine.

Benefits for the patientThis technique makes it possible to dispense with the preoperative procedure and the need for line cannulation in the anaesthetic room. The only puncture the patient will receive is for anaesthesia. If the technique proposed by Lalonde et al. is followed together with the use of small calibre needles, the patient's subjective pain during anaesthetic injection is minimal.16,31–33 Different elements have been described as possible causes of preoperative pain: the introduction of the hypodermic needle through the skin (referring to the anaesthetic puncture of the plexus in the operating theatre and the puncture in the surgical field in the small operating room using the WALANT anaesthetic technique), increased tension of the tissues in the palm as a result of injection of volume and the pain associated with the temperature or acidity of the anaesthetic.34 In our study the pain relating to anaesthetic puncture was similar to that perceived by the patients with sedation and regional anaesthesia, as previously described by authors such as Ralte et al. y Tomaino et al.35,36 In the latter study no statistically significant differences in preoperative anxiety levels were observed. In our study, we found lower levels with the axillary block technique due to the use of a sedative, but these were not statistically significant.

Without doubt, the advantage of adding adrenaline is to completely dispense with the use of an ischaemic cuff to better ensure the patient’s intraoperative wellbeing.37 The studies that were found in the literature comparing the regional versus local anaesthesia techniques do not do without the ischaemic cuff in the local technique, unlike in our study.35,36 Pain related to the cuff has been studied, and was a mean of 4.1 on the VAS scale according to Bidwai et al.13 In our study the intraoperative pain was VAS 1, with no significant differences compared to surgery under brachial plexus anaesthesia and sedation. In a previous study undertaken by Maury et al. it was demonstrated that the average tolerance time of the ischaemic cuff was 18min.38 In most operations this time is not exceeded, but complications can arise that require a longer time or that require another procedure (sometimes in trigger figure surgery more than one finger can be operated during the same surgical procedure). Furthermore, the fact that surgery is started with adrenaline does not make it impossible to place a cuff if necessary (due to uncontrollable bleeding, the need for some additional procedure…). Finally, the use of adrenaline enables surgeries to be performed in patients for whom an ischaemic cuff would be contraindicated.

In the postoperative period, significant differences in pain and the need for analgesic treatment were found. The prolongation of the anaesthetic effect can be partially explained, but we believe that other factors might coexist, such as the perception of the patients operated in the small operating room of “minor” surgery, which could influence not taking analgesia beyond 48h postoperatively.16,18,39 These differences were also observed in a study by Ralte et al. However, although the same anaesthetic techniques were compared in this study, they maintained the ischaemic cuff in operations under local anaesthesia.34

As other authors have already shown, patient satisfaction after WALANT surgery is very high, in our study also.40 In addition to high fidelity: 95% of patients would choose outpatient surgery with local anaesthesia and vasoconstrictor again. Moreover, as no sedatives are used, no fasting or discontinuation of medication is required; the patient can come to hospital unaccompanied and avoid the side effects of medication, such as nausea and vomiting. Furthermore, due to the speed of the procedure, waiting time for surgery is shortened and hospital stay is reduced to a minimum.

WALANT and anticoagulantsThe use of anticoagulants is not a contraindication for WAS surgery. There is literature that supports not discontinuing anticoagulants before hand surgery, avoiding the complications deriving from suspending them.17 In the case of warfarin there would be no contraindication below an INR of 2.5 or even 3.18,19 In our series, we operated on 4 patients maintaining their treatment with acenocumarol. We encountered no complications or wound bleeding in any of these patients.

Benefit for the health systemThe economic benefit of implementing an outpatient WAS circuit outside the operating theatre has already been demonstrated by various authors.36,41,42 In our case, this saving is around 1000€ per patient. In the case of the American Health System a saving of around $ 6275 per patient was calculated, and in the British (NHS) of around 750 pounds per patient.41,42 This amount can reach major levels if we bear in mind that we are treating two disorders (carpal tunnel and trigger finger) that are highly prevalent in the population and that are among the four most common procedures in most Spanish hospitals.23–25 Other authors have extended the indication to many more disorders, exponentially multiplying these benefits. It is true that the savings could be less if we start with surgery with local anaesthetic with a cuff, but as we have seen, it is a more uncomfortable procedure for the patient.12 In our hospital a full preoperative procedure is carried out for each patient who is to be operated in the MOS circuit. This includes chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, blood tests with coagulation and preoperative visit from the anaesthetic department. Establishing a WALANT circuit for these conditions in other centres may result in different savings according to the type and number of preoperative tests carried out.

The speed of the WALANT procedure showed higher turnover (8 patients per working day) compared to the operating theatre (5–6 patients). On the other hand, using a small operating room outside the surgical area allows the operating theatre to be freed up for other more complex procedures, to be specific, performing these 150 operations in a small operating room enabled 30 general operating theatres to be freed up for other conditions. The combination of these two factors enables the overall waiting list to be reduced not only that of the operations performed using WALANT. In the case of carpal tunnel, waiting times have been reduced by half. In a study by Leblanc et al. it was demonstrated that the use of an operating theatre (a small operating room in our case) outside the surgical area is safe for outpatients.43

Limitations of the studyThe study has several limitations. First, the operations were performed by different surgeons, although they all had a similar level of experience. Second, since this is a prospective cohort study in which the anaesthetic technique was indicated by the surgeon; it is a non-randomised study. Third, the questionnaire used for patient assessment was not validated. Finally, the cost savings were based on the resources of our hospital, and therefore the percentage of general savings cannot be generalised to all centres

ConclusionsCarpal tunnel and trigger finger surgery can be performed safely and painlessly using the 1% lidocaine and 1/100,000 adrenaline injection technique. Compared to a conventional surgery circuit with cuff, plexus and sedation, WAS surgery involves similar pre- and intraoperative pain control and greater analgesic strength during the postoperative period. The patient does not have to fast and can come to hospital unaccompanied. High user satisfaction and less use of resources are achieved, with the consequent saving and reduction of time on the waiting list.

Level of evidence IIWe removed the type of study (prospective cohort).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Far-Riera AM, Pérez-Uribarri C, Sánchez Jiménez M, Esteras Serrano MJ, Rapariz González JM, Ruiz Hernández IM. Estudio prospectivo sobre la aplicación de un circuito WALANT para la cirugía del síndrome del túnel carpiano y dedo en resorte. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:400–407.