In lumbar pain patients an aetiopathogenic diagnosis leads to a better management. When there are alarm signs, they should be classified on an anatomical basis through anamnesis and physical examination. A significant group is of facet origin (lumbar facet syndrome [LFS]), but the precise clinical diagnosis remains cumbersome and time-consuming.

In clinical practice it is observed that patients with an advanced degenerative disease do not perform extension or rotation of their lumbar spine when prompted to extend it, but rather knee flexion, making the manoeuvre meaningless. For this reason, a new simple and quick clinical test was developed for the diagnosis of lumbar facet syndrome, with a facet block-test as a confirmation.

HypothesisThe new test is better than a classic one in the diagnosis of facet syndrome, and probably even better than imaging studies.

Materials and methodsA prospective study was conducted on a series of 68 patients (01/01/2012–30/06/2013). A comparison in between: classic manoeuvre (CM), imaging diagnostics (ID), and the new lordosis manoeuvre (LM) test. Examination and block test by one author, and evaluation of results by another one.

Exclusion criteriaDeformity and instability using a physical.

ObjectiveTo determine the effectiveness of a new clinical test (LM) for the diagnosis of LFS (as confirmed by a positive block-test of medial branch of dorsal ramus of the lumbar root, RMRDRL).

StatisticsR package software.

ResultsThe LM was most effective (p<.0001; Kappa 0.524, p<.001). There was no correlation between either the CM or ID and the block-test results (Kappa, CM: 0.078; p=.487, and ID: 0.195; p=.105).

There was a correlation between ID (CAT/MR) and LM (p=.024; Kappa 0.289 p=.014), although not with CM. There was no correlation between ID (plain X-rays) and CM or LM.

ConclusionsA new test for diagnosis of LFS is presented that is reliable, quick, and simple.

Clinical examination is more reliable than imaging test for the diagnosis of LFS.

En los pacientes con lumbalgia establecer la etiopatogenia lleva al tratamiento más adecuado. En ausencia de signos de alarma, deben intentar clasificarse según el origen anatómico, mediante anamnesis y exploración física. Un grupo importante es el de origen facetario, pero su diagnóstico clínico preciso es complejo y largo.

En la práctica clínica se observa que los pacientes con un proceso degenerativo avanzado no realizan extensión ni rotaciones de la columna lumbar, sino flexión de rodillas, falseando la exploración. Por ello, se diseñó una maniobra nueva, sencilla y rápida para el diagnóstico de síndrome facetario lumbar (SFL), confirmado mediante denegación facetaria.

HipótesisLa nueva maniobra diagnóstica es mejor que la exploración clínica tradicional y, probablemente, mejor que las pruebas de imágen.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo de una serie de 68 pacientes (01/01/2012-30/06/2013). Se comparan: maniobra clásica (MC), diagnóstico por imagen (DI) y maniobra nueva (maniobra lordosante [ML]). Exploración y bloqueo por un autor, valoración efectividad por otro.

Criterios de exclusiónDeformidad o inestabilidad.

ObjetivoDeterminar la efectividad de una maniobra nueva (ML) en el diagnóstico del SFL (confirmación mediante efectividad del bloqueo rama dorsal del ramo medial de la raíz lumbar, RMRDRL).

EstadísticaPaquete R.

ResultadosML más efectiva (p<0,0001; Kappa 0,524 p<0,001); además, tanto MC como DI no se correlacionaron con resultado de la denervación (Kappa MC: 0,078; p=0,487 y DI: 0,195; p=0,105).

Hubo correlación entre DI (TAC/RM) con ML (p=0,024; Kappa 0,289 p=0,014); aunque no con MC, ni entre DI (radiología simple) con MC ni ML.

ConclusionesSe presenta una maniobra diagnóstica para SFL más fiable, rápida y sencilla.

La exploración clínica es más efectiva que las pruebas de imagen en SFL.

Lumbar pain is one of the most common reasons for medical visits. It is a frequent cause of restricted activity in people over the age of 45 years old, and it is the fifth most common cause of hospitalisation. It is also a chronic pain that may become disabling, and which affects quality of life in the social, economic and professional spheres. In 1911 Goldwaith1 hypothesised that “peculiarities in the facet joints” were the cause of lumbar instability and pain. In 1933 Ghormley coined the term “facet syndrome” as the most common cause of chronic lumbar pain.2 From a therapeutic viewpoint we will define lumbar facet syndrome (LFS) as “the set of symptoms and signs which have their origin in lumbar facet pathology and which reduce or disappear with facet denervation”, or more succinctly, as the set of lumbalgias which significantly improve with facet denervation.

About 80% of the population suffers lumbar pain. Clinical guides have been written for guidance and management of the condition. Perhaps the most inclusive diagnostic tool is that of the Medical Association of the U.S.A.,3 the first recommendation of which is to group lumbalgias into three categories: non-specific lumbalgia, lumbalgia associated with neurological compression and lumbalgia associated with another specific anatomical cause in the vertebra. LFS falls into this third group. It in turn is subdivided into disc, sacroiliac or facet pain.

Diagnosis is based on anamnesis and subsequent clinical examination.4

There is a broad range of exploratory manoeuvres (of which Revel's criteria5–7 are the most widely accepted) together with imaging studies and even neurophysiological techniques that help to a certain extent to select or rule out the mechanisms leading to lumbar pain and their most probable causes. It should be pointed out that imaging tests are not the most effective means of diagnosing LFS.8

LFS is understood to consist of the set of signs and symptoms arising due to the pain generated anatomically in the vertebra sides by various causes and which ceases therapeutically with infiltration of the area innervated by the medial branch of the dorsal ramus of the lumbar root (MBDRLR).

Exploratory manoeuvres have often been performed which may give rise to false positives, as more than one anatomical structure is involved – the injured part and others which are unharmed – so that the information obtained is not very specific. Some patients have also been observed to continue with pain after classic infiltrations in the sides of the vertebra joints, or, more often, in the MBDRLR which innervates the said joints.

When the exploratory manoeuvres are observed while we perform them, a group of patients with advanced degeneration is found to exist. When these patients are requested to extend their trunk while standing they involuntarily flex their knees without really moving their vertebral segments, giving rise to a false negative in exploration of the facets, as these vertebra did not move.

Due to this reason a new manoeuvre was designed. We term this the lordosis manoeuvre (see the description in Material and method) to oblige the segments with reduced mobility to extend, and this was correlated with the result the blockage of the MBDRLR.

HypothesisThis lordosis manoeuvre is able to give a more reliable prediction of the result of blockages of the MBDRLR than is the case with classical examination (Revel's criteria) for lumbar extension. It also takes less time, and it is probably also superior to diagnosis using imaging techniques.

Objectives- 1.

To compare the prognostic values of both manoeuvres in the same group of patients.

- 2.

To compare the efficacy of clinical diagnosis with diagnosis using imaging tests.

A descriptive, longitudinal and prospective observational study was carried out in our hospital in the period from 1 January 2011 to 30 June 2013.

Overall objectiveTo determine the efficacy of the lordosis manoeuvre in the diagnosis of LFS.

Universe and sampleThe universe was composed of all patients with lumbar pain who visited the outpatient surgery of the Spinal Column Unit of our Department in the said period (from 1500 to 2000 new patients/year), of which 68 were included in the sample as they fulfilled the eligibility criteria without any applicable exclusion criteria. All of the patients were diagnosed by the same surgeon, who also performed the denervation technique in the great majority of cases.

Eligible patient definitionPatients of both sexes older than 18 years old who visited the outpatient department of the Spinal Column Unit due to lumbar pain, diagnosed LFS and accepted facet denervation as a diagnostic technique/treatment.

Exclusion criteria- -

Not volunteering to take part in the study.

- -

The presence of associated lumbar radiculopathy.

- -

Diabetes mellitus.

- -

Previous lumbar spinal surgery.

- -

Local infection or suspicion of the same.

- -

Lumbar pain with known aetiology unconnected with the joint facets.

- -

Mental health disorders.

A bibliographical search was made for LFS, non-indexed material was gathered (doctoral theses) as well as papers published in national and international journals. Historical and logical scientific analytical methods were used, together with systemic structural methods, analysis and synthesis, dialectic and triangulation techniques. The results were shown in absolute values of minimum and maximum frequencies.

Data gathering and processingData were obtained from the clinical histories recorded in the computerised system of the Autonomous Community Health Service. They contain examination data, clinical course, the treatment that was applied and evolution of the patient following infiltration, together with other variables used in the study.

Data were gathered by another author who was not involved in diagnosis or denervation procedures.

Description of the lordosis manoeuvrePhase I: the patient in prone decubitus on a firm flat surface (examination couch) with the arms extended on either side of the body and the head to one side and resting on the couch.

Phase II: the patient is asked to raise his head and chest from the previous position by resting on his elbows and forearms, with the humerus vertical and without raising the pelvis, giving rise to a hyperlordotic lumbar arch. The reappearance of the pain that led the patient to visit is verified.

Phase III: the patient is requested to return to the first position of Phase I, and he is asked whether in this position the pain which arose beforehand (in Phase II) is less or has disappeared.

Statistical study: this was undertaken in the Epidemiology Unit of our hospital, using the R statistical package as the tool for tests to compare averages, the Chi-squared test and symmetrical measurements (Kappa).

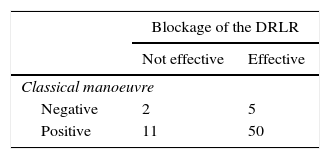

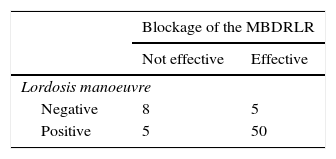

ResultsThe efficacy of infiltration depending on the clinical examination test used: with the classic manoeuvre (test 1), when the manoeuvre was positive infiltration was effective in 50 patients while in 11 it was not. When the manoeuvre was negative it was only effective in 5 patients, while it was not effective in 2 (Table 1). On the other hand, with the new manoeuvre (the lordosis manoeuvre, test 2 in the table) when this was positive infiltration was effective in 50 cases, while it was only ineffective in 5 of these. When it was negative it was only effective in 5 patients, while it was ineffective in 8 (Table 2).

The statistical study showed a level of significance of the hypothesis (that the lordosis manoeuvre – test 2 – is superior to the classic manoeuvre – test 1): (P<0.0001), Kappa 0.524 (significance<0.001).

When the hypothesis that the predictive value of the lordosis manoeuvre (see Table 2; VPP=0.9; VPN=0.61) would make it possible to definitively eliminate the previous blockage and perform rhizolysis without diagnostic confirmation of the said blockage, although the data showed a clear tendency, they did not achieve statistical significance.

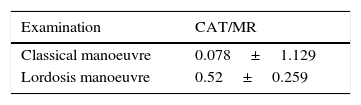

Correspondence of the results of exploratory manoeuvres with imaging signs: (a) in CT scan or MRI (Table 3), when no clear signs were detected of facet arthrosis the classical manoeuvre was negative in 2 patients and positive in 13, while the lordosis manoeuvre was negative in 6 cases and positive in 9; on the other hand, when signs of facet arthrosis were detected the classical manoeuvre was negative in 5 patients and positive in 52, while the lordosis manoeuvre was negative in 7 and positive in 49; (b) in simple X-rays: when no clear radiological signs were detected of facet arthrosis the classical manoeuvre was negative in 4 patients and positive in 26, while the lordosis manoeuvre was negative in 8 cases and positive in 22; in turn, when radiological signs of facet arthrosis were detected the classical manoeuvre was negative in 3 patients and positive in 39, while the lordosis manoeuvre was negative in 5 and positive in 36.

The relationship between the clinical manoeuvres and simple X-rays was not significant, while that between CAT/MR and the clinical manoeuvres was not significant for the classical manoeuvre although it was for the lordosis manoeuvre (test 2): (P=0.024) Kappa 0.289 (sig. 0.014).

DiscussionAlthough the efficacy of blocking the MBDRLR varies statistically from one series to another, in general the majority refer to its usefulness in the management of facet syndrome lumbar pain. This is so for the study by Dr. OspinaI,9 who obtained a 78% improvement after using the procedure in his patients. He also refers to the work published by Gorbach,10 who achieved an efficacy of 74% in his series. These authors state that the efficacy of the technique confirms the facet syndrome diagnosis, and based on the results of our research we agree with this. Nevertheless, to achieve positive results this medical condition has to be correctly diagnosed, and for this we have to underline that clinical examination was more relevant for us than imaging tests (CT scan or MRI).

Tomé-Bermejo et al.11 also admit that imaging studies may not correspond to clinical reality, and that therefore their diagnostic specificity could be altered, while many imaging findings have no correlation with symptoms. This has been argued since the end of the 1980s, when Jackson et al.12 stated that they had found no connection between radiological signs of degenerative changes and a positive response to facet blocking in 390 patients. Nor were Schwarcer et al.13 able to find a relationship between CT scan findings and positive response to anaesthetic facet blocking in 63 patients, and this was also the case more recently for Manchicanti et al.6

Almost all of the works revised describe the degree to which facet infiltrations are effective, although this is not the case for the clinical examination manoeuvres developed to diagnose patients with LFS. This has been a relative limitation when comparing this study with other similar ones on this subject. On the other hand, it is hard to define efficacy in percentage terms, even though this is attempted in the literature. We believe that this is an excessive attempt to quantify pain, and that in this specific case efficacy may be defined as a clear improvement (the disappearance of the clinical problem for the patient) with an obvious temporal relationship.

Falco14 and Manchicanti6 therefore generally accept blockage of the MBDRLR to be a reliable procedure, while injection into the joints is less so (Jackson12). The bibliography also underlines the importance of psychological factors in the management of patients with LFS (van Wijk15), as they play a positive role if the patient adapts to situations and a negative one if there is psychological vulnerability, a lack of control over their life, a high level of anxiety or a tendency to exaggerate negative events.

Tomé-Bermejo et al.11 also refer to the lack of a validated and effective procedure when they state that “the greatest restriction when undertaking a prospective study with facet syndrome lumbar pain patients is the lack of a definitive diagnostic method”.

If we attempted to diagnose LFS by a single method such as in situ infiltration this too would run the risk of increasing the number of false positives in the series, which could even reach 38%.16,17 This supports our conclusion that diagnosis should not be restricted to any single procedure, and that the role and usefulness of clinical examination should be increased, which in our case was more accurate with the new manoeuvre we propose (test 2).

However, some publications such as the one by Acevedo González et al.17 cite high figures for sensitivity (95%) and specificity (96%) using manoeuvres they designed themselves, surpassing the 90% attained by the classical hyperextension manoeuvre with lumbar column rotation. Clinical criteria were used to confirm this, while on the contrary the efficacy of our manoeuvre was confirmed by the criterion of MBDRLR blockage.

We believe it is important to underline the time saved in patient visits, as references to Revel's criteria mention examination lasting from 15 to 20min7 to reach a diagnosis, while the manoeuvre we suggest takes from 15 to 20s.

Finally, as well as the intrinsic efficacy of the suggested manoeuvre, we believe that the superiority of clinical examination over imaging tests should be emphasised, and that patients with a positive classical manoeuvre and a negative test 2 responded poorly to the MBDRLR blockage (which highlights the greater discriminatory power of the proposed manoeuvre).

Once again, the explanation lies in the clinical observation that patients with advanced lumbar degeneration neither extend nor rotate their lumbar column during examination, giving rise to the need for a sensitive, simple and fast manoeuvre (in this order) to bring about these movements in a quasi-ankylosed spinal column.

Conclusions- 1.

A manoeuvre (termed the lordosis manoeuvre) is presented for the diagnosis of lumbar facet syndrome which, in comparison with the classical examination, is more reliable, reproducible and effective in diagnosing LFS.

It also takes less time than the said classical manoeuvres.

- 2.

The lordosis manoeuvre is more effective than imaging tests (CT scan/MRI) in the diagnosis of LFS, while the classical examination is not.

Level of evidence II.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments took place using human beings or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work governing the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data are shown in this paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Díez-Ulloa MA, Almira Suárez EL, Otero Fernández M, Leborans Eiras S, Collado Arce G. Efectividad de la maniobra lordosante en el diagnóstico del síndrome facetario lumbar. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:221–226.