To report the design and outcomes obtained during the first operational years of the Orthogeriatric Unit (OGU) established in the Zaragoza-1 (Spain) Health-Sector.

Materials and methodsA total of 494 patients >70 years old treated in the OGU from February 2009 to December 2012. An analysis was performed using the following variables: demography, previous functional level, comorbidities, surgical delay, fracture type and surgical technique, complications, hospital stay, functional outcomes, destination after hospital discharge, and short- and long-term mortality.

ResultsMean age 85.22 years. High incidence of comorbidities (Charlson Index): 24.3%. Dementia: 38.5%. Surgical delay: 2.57 days. Mean hospital stay between admission and discharge/transfer to convalescence unit, 20.9 days (Traumatology 6.45+OGU 14.49). More than a third (34.6%) of patients suffered from delirium. Mean functional improvement (Barthel index at hospital discharge–Barthel index at hospital admission): 27.25 points. Montebello index: 0.49. In-hospital mortality: 6.9%.

ConclusionHip fracture is such a frequent and disabling pathology among the geriatric population that its treatment requires an interdisciplinary approach. This must be managed by the geriatrician, who has to assure the continuity and integration of the diverse treatment and care schedules, with the participation of the entire professional team in the decision-making process. We are very satisfied with the creation of our interdisciplinary Unit that enables us to report competitive outcomes. We believe that the progression of this Unit from providing subacute to acute care will improve the general outcomes in the future.

Presentar el diseño y los resultados de los primeros años de funcionamiento de la unidad de ortogeriatría (UOG) constituida en el Sector Sanitario Zaragoza I para atender a los pacientes ancianos con fractura de cadera.

Material y métodosCuatrocientos noventa y cuatro pacientes mayores de 70 años ingresados en la UOG de 2009 a 2012. Se estudiaron datos demográficos, funcionales, comorbilidad, demora quirúrgica, tipo de fractura y técnica quirúrgica utilizada, complicaciones, estancia hospitalaria, resultados funcionales, destino al alta y mortalidad a corto y a largo plazo.

ResultadosEdad media 85,22 años. Comorbilidad alta según el índice de Charlson: 24,3%. Demencia: 38,5%. Demora quirúrgica: 2,57 días. Estancia media del proceso agudo: 20,9 días (traumatología 6,45+UOG 14,49). Presentó delirium el 34,6%. Ganancia funcional media (índice de Barthel al alta–índice de Barthel al ingreso): 27,25 puntos. Índice de Montebello: 0,49, mortalidad intrahospitalaria: 6,9%.

ConclusiónLa fractura proximal de fémur es una enfermedad tan frecuente e incapacitante en la población geriátrica que es indiscutible un abordaje interdisciplinar en el que el geriatra gestione la continuidad y la integración asistencial, con la participación del resto de profesionales en la toma de decisiones. Estamos muy satisfechos de haber podido crear nuestra Unidad de trabajo interdisciplinar y de mostrar unos resultados bastante competitivos. Creemos que la evolución de dicha unidad desde la atención subaguda a la aguda mejorará dichos resultados en el futuro.

Traumas that affect the elderly patient are extensive and varied. The most representative is the fracture of the proximal end of the femur, incorrectly called a “hip fracture”. It is the most important complication in osteoporosis, both for the morbidity and mortality it involves and for the costs it generates.1,2 Its incidence in Spain ranges between 500 and 600 cases per 100,000 elderly people and year. These figures jump up to 700 cases per 100,000 and year for women and drop to some 300 cases per 100,000 and year for men.3,4 Some authors speak of a decrease in fracture risk adjusted to age.5,6 Even so, the forecast is for significant increase (even doubling) in the coming decades. The figures related to mortality are alarmingly high in all the stages of the process, remaining around 5% during hospital stay, 15% at 3 months and 25–30% at 1 year.7,8 How easy it is for these fractures and their treatment to cause dependency is also extremely well known.9 Insofar as the economic cost, in the words of Dr Mesa Ramos10 (speaking about the year 2009), “Spain labours under one of the highest hospital costs per hip fracture, with 9936 euros per admission related to this pathology” (sic.). And this is not even counting the costs derived from complications and their consequent functional losses.

The traditional model for treating this illness was based on direct attention from traumatologists and occasional later support from specialists in internal medicine and in rehabilitation. The appearance, over the last few decades, of new models based on comprehensive interdisciplinary attention in what are known as orthogeriatric units has modified the previous model. These units (or better said, the work model that inspires them) were described in Great Britain in the 1960s and 1970s.11–13 Their spread in Spain has been progressive, heterogeneous and conditioned by hospital resources. Many studies have shown their efficacy: improved diagnostic precision, reduced complications and mortality, shortened surgical delay and hospital stay, increased functional improvement and reduced institutionalisation.14,15

Our objective was to present the design of and the results from the first years of operation of the Orthogeriatric Unit (OGU) set up in the Zaragoza-I Healthcare Sector (Spain) to attend elderly patients with hip fractures. Our intention is not to compare our system with any of the other orthogeriatric units in the country, but rather to describe the specific features of our model and to show the first results.

Materials and methodsThe OGU for the Zaragoza-I Sector opened in February 2009 with 8 beds. It is located in the Geriatrics Service at the Nuestra Señora de Gracia Hospital. The traumatology service is located in another Zaragoza hospital (Hospital Royo Villanova). Consequently, the OGU arose as a subacute unit, receiving patients older than 70 years old at 48–72h after surgical intervention of proximal femur fractures. Although with unstoppable progression, we can say that the traumatology service has attended a mean of about 150 patients aged over 70 years with hip fractures in the years analysed; this represents almost 1% of the population of this age covered by the hospital (15,764 people as estimated on 1 October 2013).

Before transfer, the criterion of maximum priority in surgical treatment is applied to all patients, once there is clinical stability. During admission to the Unit, the patients are assessed using geriatric evaluation, detection of comorbidities, postoperative monitoring, study of the fall, rehabilitation treatment and discharge plans with occupational therapist-given training and practice for relatives, as well as suggestions and treatment to prevent new falls and fractures. In addition to the initial assessment by a geriatrician, physiatrist, physical therapist and nurse, the patient receives daily visits by the geriatrician and, if necessary, the traumatologist. The team (geriatrician, traumatologist, physiatrist, nurse) also visit the patient jointly once a week. The geriatrician manages healthcare integration and continuity, with the other professionals participating in consensual decisions.

Our sample was composed of 494 patients, all the patients admitted to the unit from its opening up to the end of December 2012 (10 beds). They were elderly patients aged over 70 years (occasionally there was someone of a lesser age in geriatric status) with proximal femur fracture as the main diagnosis. Exclusion criteria were less than 70 years old without geriatric criteria, medical contraindication for transfer to the hospital where the geriatric service was located, patients incapable of benefiting from rehabilitation because of their prior functional status (bed–armchair living), patients with exceptionally quick satisfactory evolution and patients that refused transfer between hospitals.

The variables analysed were:

- •

Epidemiological: age, sex, place, moment and cause of the fall.

- •

Previous falls.

- •

Comorbidity (Charlson index).

- •

Prior geriatric valuation, on hospital discharge, at 6 months and at 1 year: basic and instrumental activities of daily living (Barthel plus Lawton and Brody indexes), cognitive assessment (Pfeiffer test), nutritional assessment (the short form Mini Nutritional Assessment [mini-MNA]) and environmental evaluation.

- •

Type of fracture and surgical technique.

- •

Previous and associated fractures.

- •

Hospital stay.

- •

Causes of surgical and transfer delays.

- •

Need for transfusions.

- •

Local and general complications.

- •

Rehabilitation treatment.

- •

Assistance required for walking, before and after the fracture.

- •

Functional gain (Barthel index on discharge-Barthel index on admission) and Montebello rating factor score index (percent of functional loss recovered on discharge with respect to that suffered after the hip fracture)=(Barthel index on discharge−Barthel index on admission)/(prior Barthel index−Barthel index on admission).

- •

Destination upon discharge from the hospitalisation unit.

- •

Mortality.

All the variables were analysed statistically using the SPSS 19.0 package. Statistical significance was set to values of P<.05. A descriptive study (mean, standard deviation [SD], frequency, percentage and 95% confidence interval [CI]) and bivariate analysis were carried out, using the Chi square test, Student's t-test and ANOVA according to the nature of the variables. Residual analysis was performed for qualitative variables in which the Chi square test was significant.

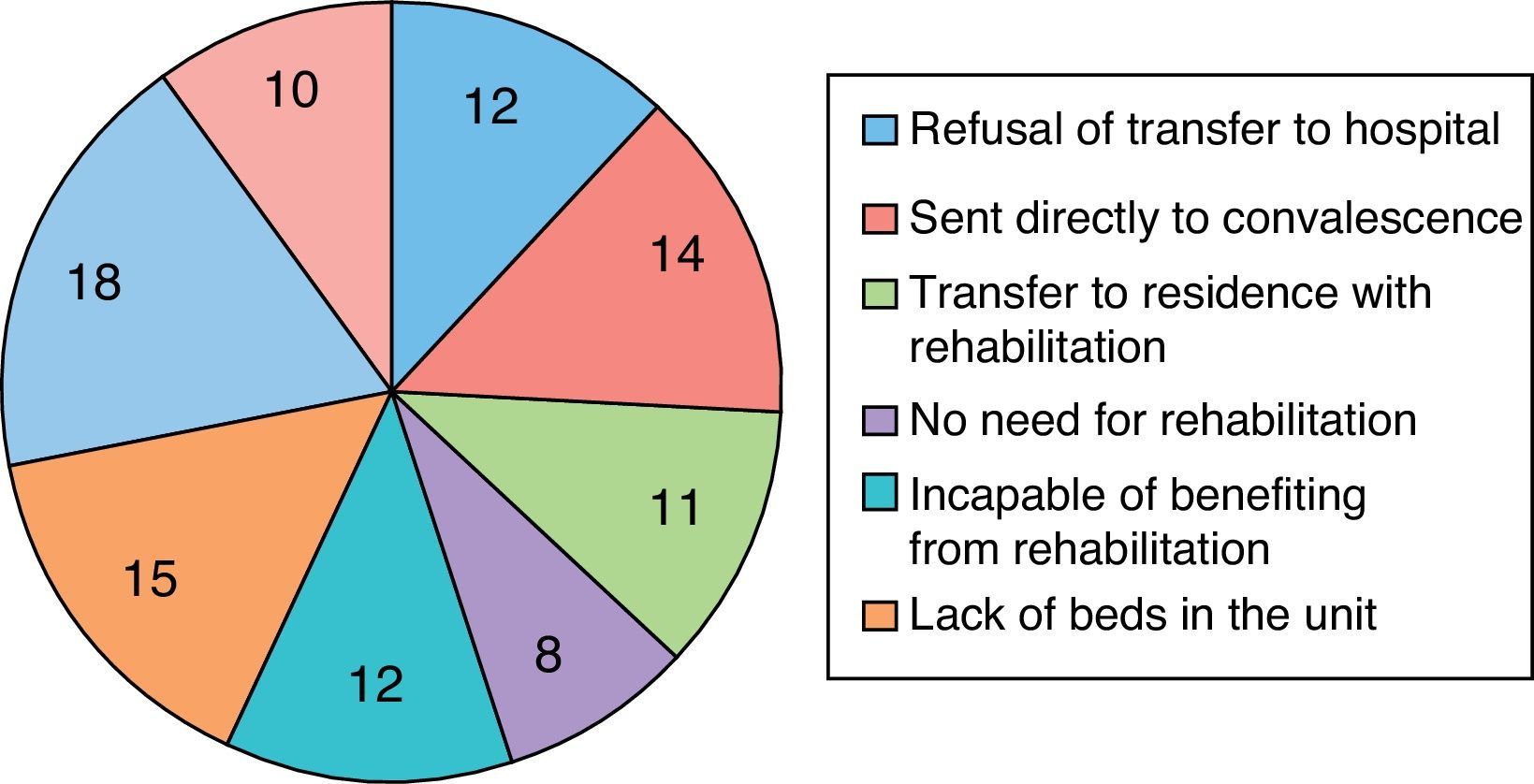

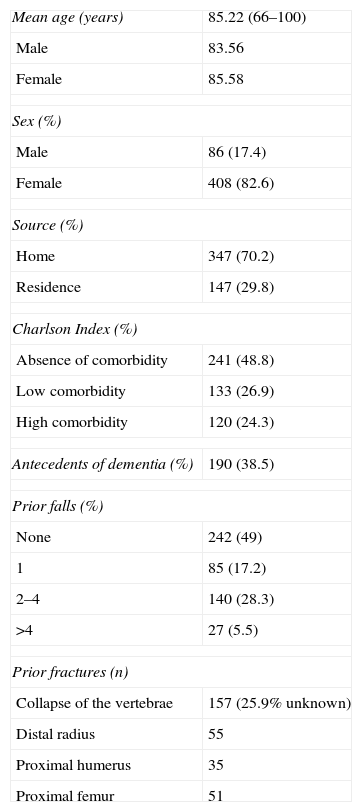

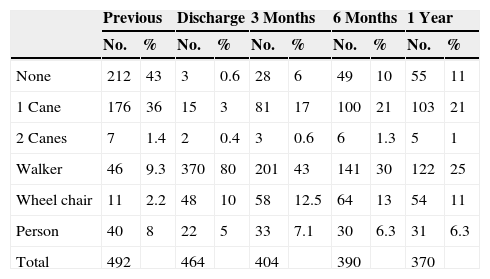

ResultsIn the Zaragoza-I Sector, 594 individuals suffered a proximal femur fracture between February 2009 and December 2012. Among these, 494 were treated at the orthogeriatric unit. The mean age of these patients was 85.22 years (CI: 66–100; SD: 6.005): 83.56 years (CI: 82.38–84.74; SD: 5.5) for the men and 85.58 years (CI: 85–86.2; SD: 6.05) for the women. Females represented 82.6% of the sample. Table 1 shows the general patient characteristics, while Fig. 1 indicates the main reasons for not being transferred to the Unit.

General characteristics.

| Mean age (years) | 85.22 (66–100) |

| Male | 83.56 |

| Female | 85.58 |

| Sex (%) | |

| Male | 86 (17.4) |

| Female | 408 (82.6) |

| Source (%) | |

| Home | 347 (70.2) |

| Residence | 147 (29.8) |

| Charlson Index (%) | |

| Absence of comorbidity | 241 (48.8) |

| Low comorbidity | 133 (26.9) |

| High comorbidity | 120 (24.3) |

| Antecedents of dementia (%) | 190 (38.5) |

| Prior falls (%) | |

| None | 242 (49) |

| 1 | 85 (17.2) |

| 2–4 | 140 (28.3) |

| >4 | 27 (5.5) |

| Prior fractures (n) | |

| Collapse of the vertebrae | 157 (25.9% unknown) |

| Distal radius | 55 |

| Proximal humerus | 35 |

| Proximal femur | 51 |

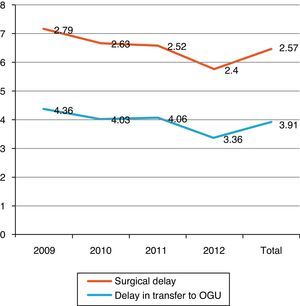

With reference to functional assessment, more than 75% of the patients were independent or had slight dependence for the basic activities of daily life. No cognitive deterioration was found in 41.8% and 56.3% presented malnutrition or nutritional risk.

Of the 494 patients with fracture, 83% fell in their homes, the majority of them in the morning (43.8%). The most frequent causes of falling were imbalance in transfers or turns, 17.8%; tripping, 14%; and slipping, 13%. No reason was found in 17.6% of the cases.

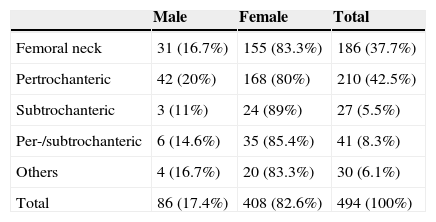

The different types of proximal femur fracture distributed among gender can be seen in Table 2. As for distribution by age, the older the patient, the lower the incidence of femoral neck fractures was: 43.6% in the patients 71–80 years old, 36.2% in those 81–90 years and 30.2% in those aged more than 90 years. In the older patients, pertrochanteric fractures were the most frequent (44.2%).

Distribution of fracture type by sex.

| Male | Female | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral neck | 31 (16.7%) | 155 (83.3%) | 186 (37.7%) |

| Pertrochanteric | 42 (20%) | 168 (80%) | 210 (42.5%) |

| Subtrochanteric | 3 (11%) | 24 (89%) | 27 (5.5%) |

| Per-/subtrochanteric | 6 (14.6%) | 35 (85.4%) | 41 (8.3%) |

| Others | 4 (16.7%) | 20 (83.3%) | 30 (6.1%) |

| Total | 86 (17.4%) | 408 (82.6%) | 494 (100%) |

No statistically significant differences were found between fracture type and the following variables: sex, time of surgical delay, days of OGU stay and need for transfer to the convalescence unit.

In 43 patients, other fractures were associated: distal radius, 13 (2.6%); proximal humerus, 11 (2.2%); and others (pelvic branches, ribs, etc.), 19 (3.8%).

As for the surgical technique used, 10 (2%) total prostheses and 185 (37.4%) partial prostheses were placed; in the extracapsular fractures, a short keyhole nail was used in 236 patients (47.8%) and a long nail in 63 (12.8%).

Unless it was totally contraindicated, the patients underwent erythrocyte-stimulating treatment. There were 232 patients (46.96%) transfused, with a mean of 2.38 units of packed red cells per patient (CI: 1–10; SD: 1.34). Patients with cervical fractures need fewer transfusions in comparison with the rest (28 patients against 56; P=.017).

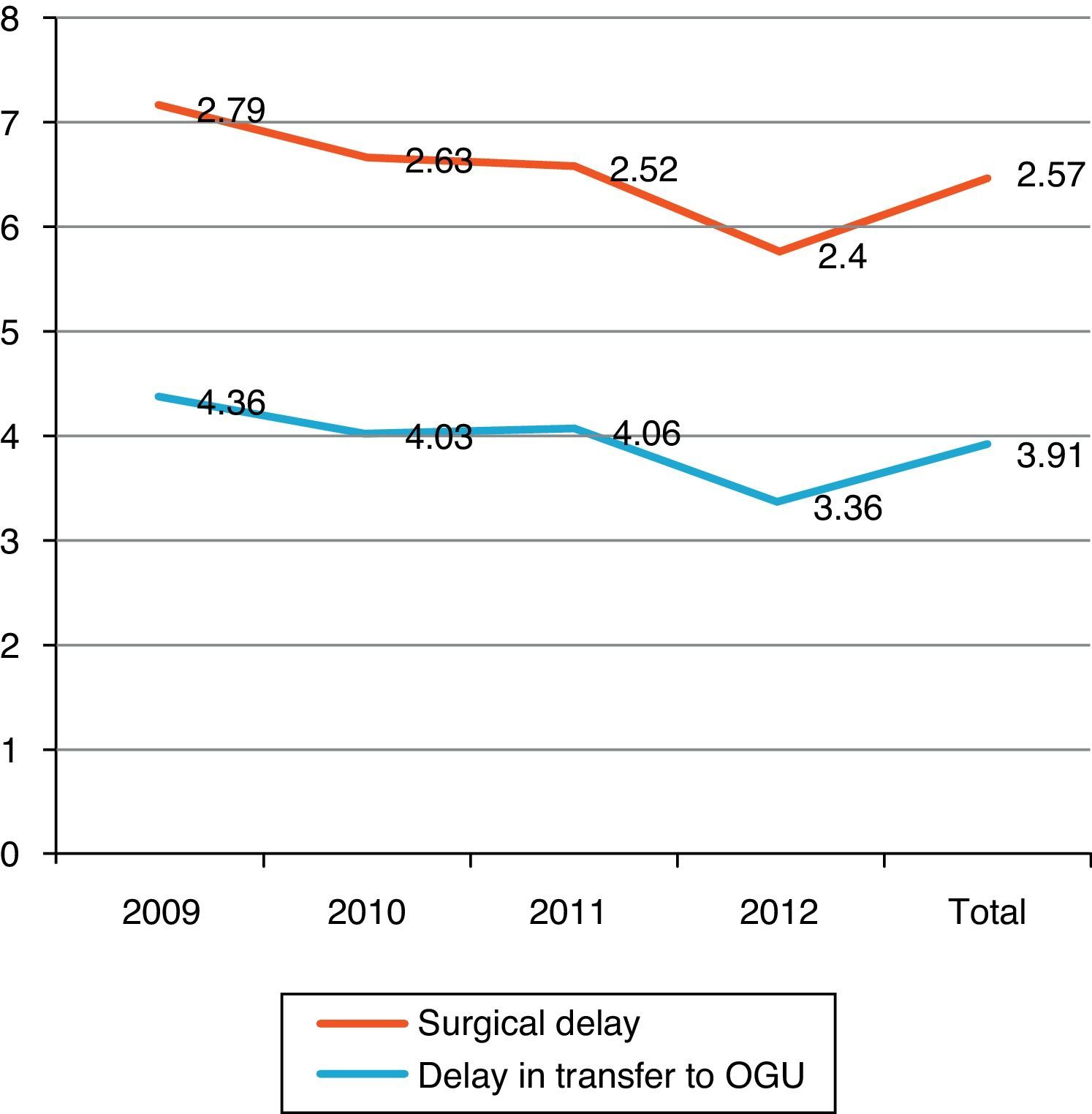

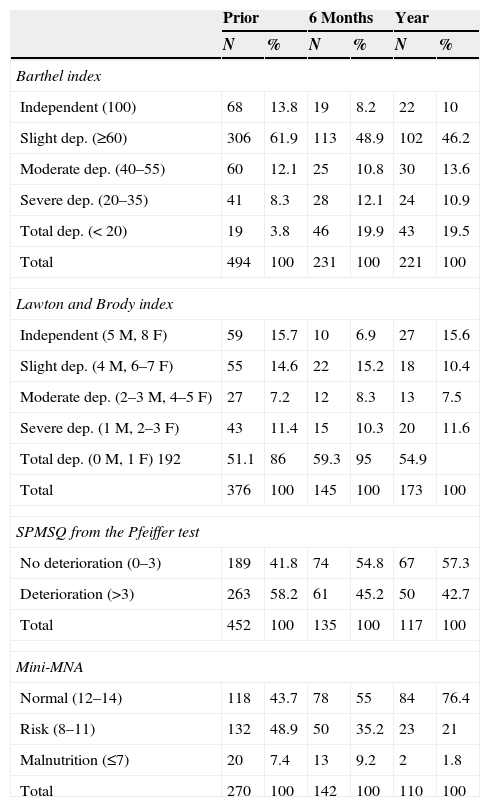

Mean time of surgical delay was 2.57 days (CI: 0–21; SD 2.017, median 2). The most frequent reasons for delay (>48h) were reversal of anticoagulation, 85 (17%) cases; clinical decompensation, 25 (5%); and organisational cause, 88 (18%).

In 161 patients (36.3%), there was excessive delay in the transfer from the traumatology service to the OGU (>72h). The main reasons were lack of beds, 63 cases (14.2%); rejection of transfer by the internal medicine department of the hospital of origin because of a very serious intercurrent clinical process, 60 (13.5%); surgical complication, 5 (1.1%); and organisational problem, 33 (7.4%). Fig. 2 shows the length of delay distributed by years.

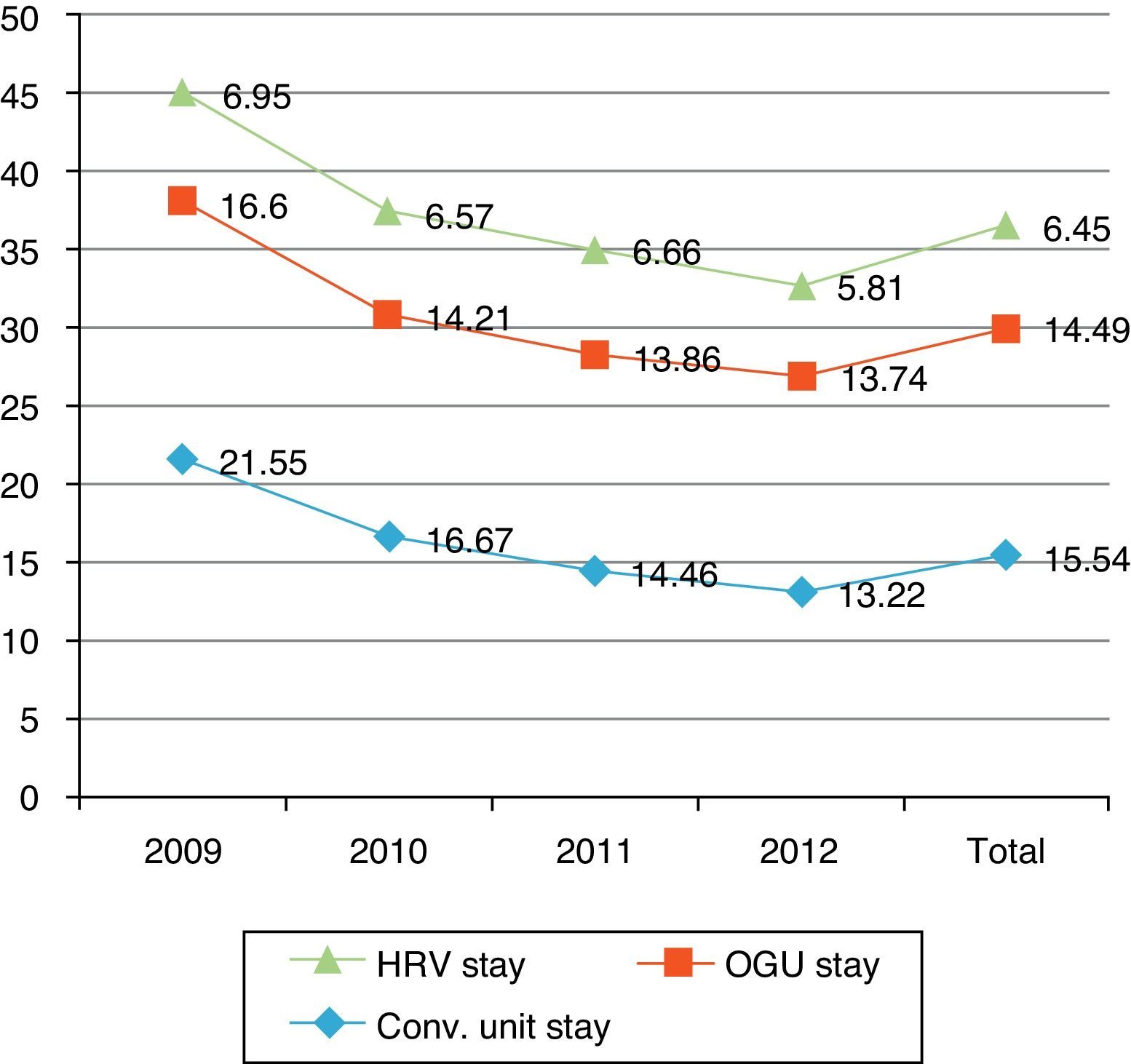

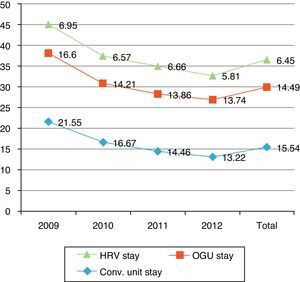

Mean stay of an acute process (traumatology+OGU) was 20.9 days (CI: 5–52; SD: 6.89). In the Hospital Royo Villanova (HRV), the mean stay was 6.45 days (CI: 2–28; SD: 3.35) and in the Nuestra Señora de Gracia Hospital, it was 14.49 days (CI: 1–47; SD: 6) (Fig. 3). The mean stay in surgical beds was slightly longer for patients with a subtrochanteric fracture, whose mean was 7.6 days, or 1.14 days more than the other patients (P=.04).

Of the 494 patients treated in the OGU, 90 (18.22%) had to be transferred to the convalescent unit, with a mean stay in that unit of 15.54 days (CI: 2–46; SD: 10.34) (Fig. 3). These patients were older than the rest (86.3 vs 84.98 years; P=.052).

Considering the overall stay for patients who required transfer to the convalescent unit (traumatology+OGU+convalescence), per-/subtrochanteric fractures involved the longest stay (27.6 days), 4 days more than other fractures. However, there was no statistically significant difference (P=.07).

As for complications, 112 patients (22.7%) presented 1 or more local complications. The most frequent of these were seroma (71 patients), superficial wound infection with positive culture (11), local haematoma (18), deep infection (5), loss of fragment reduction (4), haemarthrosis (6) and lymphedema (7).

The main general complications were anaemia (71.3%), faecal impaction (48.2%) and delirium (34.6%). Complications that occurred with lesser frequency were respiratory infection, 85 cases (17.2%); urinary infection, 84 (17%); heart failure, 43 (8.7%); pulmonary thromboembolism, 2 (0.4%); and deep venous thrombosis, 1 (0.2%).

Almost all patients (92.71%) received rehabilitation during their hospital stay. In addition, 26.4% continued treatment at the geriatric day hospital after their hospital discharge.

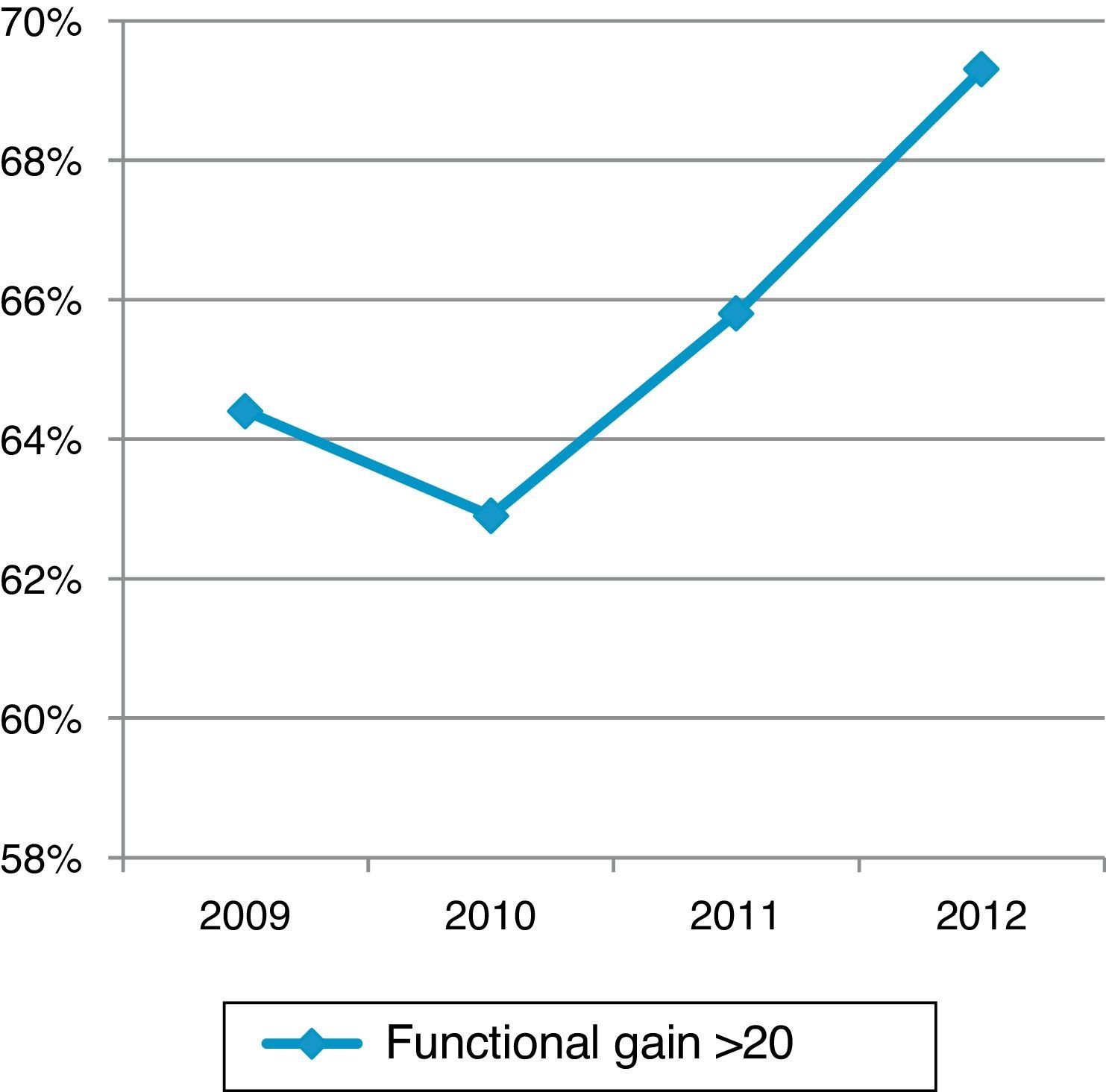

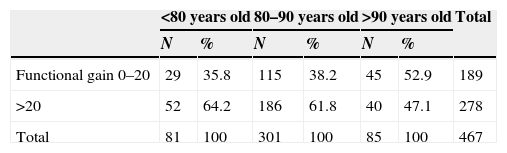

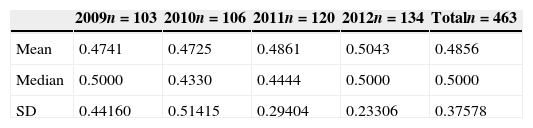

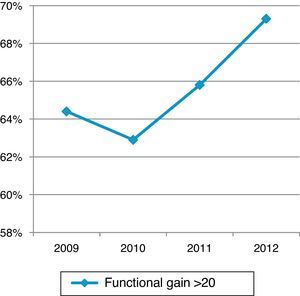

Mean functional gain (Barthel index on discharge−Barthel index on admission) was 27.25 points (SD±18.16), with the gain being more than 20 points in almost 60% of the patients. These percentages, as can be seen in Fig. 4, improved progressively from 2010 onwards. As indicated in Table 3, the older the patient, the smaller the functional gain was. Measuring this functional gain with the Montebello index, almost 42% of the patients had an index >0.5. This index has been increasing over the years analysed, up to a mean and median value of 0.5 in 2012 (Table 4).

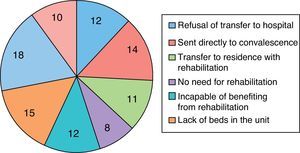

Table 5 shows the need for assistance in walking over the first post-fracture year.

Assistance required for walking during the process.

| Previous | Discharge | 3 Months | 6 Months | 1 Year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| None | 212 | 43 | 3 | 0.6 | 28 | 6 | 49 | 10 | 55 | 11 |

| 1 Cane | 176 | 36 | 15 | 3 | 81 | 17 | 100 | 21 | 103 | 21 |

| 2 Canes | 7 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.6 | 6 | 1.3 | 5 | 1 |

| Walker | 46 | 9.3 | 370 | 80 | 201 | 43 | 141 | 30 | 122 | 25 |

| Wheel chair | 11 | 2.2 | 48 | 10 | 58 | 12.5 | 64 | 13 | 54 | 11 |

| Person | 40 | 8 | 22 | 5 | 33 | 7.1 | 30 | 6.3 | 31 | 6.3 |

| Total | 492 | 464 | 404 | 390 | 370 | |||||

There was statistically significant association (Pearson's chi-square statistic, Phi and Cramer's V; P=.0001) between:

- 1.

Functional status before the fracture:

- a.

Not require help in walking before the fracture and

- -

Require a cane on hospital discharge.

- -

Not require help at 3, 6 and 12 months post-fracture.

- -

- b.

Need to use a cane previously and require a walker at 3, 6 and 12 months post-fracture.

- c.

Need to use 2 canes or a walker previously and continue needing them at 3, 6 and 12 months.

- d.

Require a wheel chair previously and continue needing it on discharge, at 6 and 12 months.

- a.

- 2.

Functional status on discharge:

- a.

Not require help on discharge and not require it at 3 and 6 months.

- b.

Require a cane on discharge and still require it at 3 months, but not need any help at 6 and 12 months.

- a.

Table 6 shows the evolution of the patients’ functional, mental and nutritional status. We found statistically significant associations (Pearson's Chi-square statistic, Phi and Cramer's V; P=.0001) between the following: (1) being independent previously for basic activities of daily life and continuing to be so at 6 months and 1 year post-fracture; (2) having slight dependence previously and continuing the same at 1 year; and (3) having total, severe or moderate dependence prior to the fracture and being totally dependent total at 6 months and 1 year post-fracture.

Functional, mental and nutritional status during the process.

| Prior | 6 Months | Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Barthel index | ||||||

| Independent (100) | 68 | 13.8 | 19 | 8.2 | 22 | 10 |

| Slight dep. (≥60) | 306 | 61.9 | 113 | 48.9 | 102 | 46.2 |

| Moderate dep. (40–55) | 60 | 12.1 | 25 | 10.8 | 30 | 13.6 |

| Severe dep. (20–35) | 41 | 8.3 | 28 | 12.1 | 24 | 10.9 |

| Total dep. (<20) | 19 | 3.8 | 46 | 19.9 | 43 | 19.5 |

| Total | 494 | 100 | 231 | 100 | 221 | 100 |

| Lawton and Brody index | ||||||

| Independent (5M, 8F) | 59 | 15.7 | 10 | 6.9 | 27 | 15.6 |

| Slight dep. (4M, 6–7F) | 55 | 14.6 | 22 | 15.2 | 18 | 10.4 |

| Moderate dep. (2–3M, 4–5F) | 27 | 7.2 | 12 | 8.3 | 13 | 7.5 |

| Severe dep. (1M, 2–3F) | 43 | 11.4 | 15 | 10.3 | 20 | 11.6 |

| Total dep. (0M, 1F) 192 | 51.1 | 86 | 59.3 | 95 | 54.9 | |

| Total | 376 | 100 | 145 | 100 | 173 | 100 |

| SPMSQ from the Pfeiffer test | ||||||

| No deterioration (0–3) | 189 | 41.8 | 74 | 54.8 | 67 | 57.3 |

| Deterioration (>3) | 263 | 58.2 | 61 | 45.2 | 50 | 42.7 |

| Total | 452 | 100 | 135 | 100 | 117 | 100 |

| Mini-MNA | ||||||

| Normal (12–14) | 118 | 43.7 | 78 | 55 | 84 | 76.4 |

| Risk (8–11) | 132 | 48.9 | 50 | 35.2 | 23 | 21 |

| Malnutrition (≤7) | 20 | 7.4 | 13 | 9.2 | 2 | 1.8 |

| Total | 270 | 100 | 142 | 100 | 110 | 100 |

Dep.: dependency; F: female; M: male; SPMSQ: short portable mental status questionnaire.

With respect to instrumental activities of daily life, we found statistically significant (Pearson's chi-square statistic, Phi and Cramer's V, P=.0001) association between maintaining the same level of pre-fracture dependence as at 6 and 12 months post-fracture.

On hospital discharge, 371 patients (75.1%) returned to their original residence, 28 (5.7%) were institutionalised temporarily and 24 (4.9%) were institutionalised permanently. At 1 year, 309 (62.5%) remained in their original residence.

Thirty-four patients (6.9%) died in hospital. Of these, 19 (3.8%) died during their OGU stay and 15 (3.27%) in the convalescent unit. Following hospital discharge, 8.9% of the patients died during the first 6 months and 5%, between the 7th and the 12th months. We found statistically significant association between a pre-fracture requirement of a wheel chair or needing the help of another person to walk, and dying within the first 3 months or within the first year, respectively.

DiscussionIt is undeniable that the osteoporotic fracture of the proximal femur is linked to the progressive ageing of the population. This can be seen in any of the traumatology services in the country. Consequently, we have to admit that ageing is a basic factor in evaluating the increased incidence of these fractures over the last few decades. We should remember that, in Spain, the population statistically considered as elderly (65 years or more) has increased considerably in the last years, passing from 14.92% in 1997 to 16.62% in 200816 and, according to the Spanish National Statistics Institute estimations, to 17.15% at the end of 2011. Traditionally, the Autonomous Community of Aragón is undergoing a more extreme ageing process, reaching 19.96% inhabitants of 65 years or older by this same time period.17

In this article, we describe the first 4 years of experience in the joint management by the geriatrics and traumatology services of Sector I in Zaragoza of elderly patients with hip fractures. In contrast to most of the orthogeriatric units in Spain, ours is physically located within the geriatrics service. The special geographical characteristics of the area (hospitals 5km apart) and the distribution of the services (lack of geriatrics in the Hospital Royo Villanova) made the conception of the unit more similar to the classic model described by Irvine and Devas12 in its functioning. However, the notably shortened time for transfer and length of stay are more in agreement with current views. Our model presents similarities with the British classic one, such as being located in two different hospitals and having a joint weekly visit by the traumatologist, geriatrician, physiatrist and nurse. The main differences are in a quicker transfer to the unit (3 days compared to 5) and a shorter mean stay (2 weeks instead of 5), with the convalescent unit available when necessary. During the stage we describe, geriatrics has been involved from the immediate postoperative period up to the end of the process at 1 year post-fracture by outpatient follow-up. The internal medicine department has handled the pre- and perioperative stage. However, at present, and from October 2013, the situation changed: joint patient management has been extended to the pre- and perioperative period in the unit in the Nuestra Señora de Gracia Hospital. Within a few years, we will be able to compare the 2 models.

The typical profile for our patients is that of a woman older than 85 years old who lives in her home accompanied by someone, who walks without help or with minimum help, has a lack of comorbidity or low comorbidity and has some degree of cognitive deterioration; the woman is independent or has slight dependence in the basic activities of daily life, suffers from malnutrition or is at risk for it, and has had a trochanteric fracture.

As we have just indicated, there is a clear dominance of females in our patients. This is in agreement with the rest of the series, but our mean age is somewhat older (85.22 years).4,18

Patient sources and patient destinations upon hospital discharge and at the end of follow-up final vary greatly in the various series consulted.19,20 Our data coincide with those published by González Montalvo in 2011,21 with a clear majority of patients from their homes. Among the consequences of hip fracture in the elderly is institutionalisation from changed functional status, greater dependence and inability of relatives to take care of them. In our study, only 5% required final de novo institutionalisation, while 75% returned to their place of origin. This percentage dropped to 12% at the end of follow-up, a fact that we consider good and in agreement with other series.22

The comorbidity in our group was low compared to other authors.18 However, 40% of our patients presented a history of dementia, in agreement with other studies; this fact casts a shadow over the functional and vital prognosis, as is clearly admitted.23,24

The patients analysed presented good prior functionality, in line with those of other studies.9,18,21 However, more than half of them suffered from malnutrition or were at nutritional risk according to the scale used. A similar percentage had suffered more than 1 fall, at least, in the last year (in most cases, due to imbalance). These facts agree with what Friedman et al.25 communicated in a recent publication: the risk of falls in individuals aged 80 years or over exceeds 40% annually.

As in the majority of the series, a good part of our patients had suffered fractures because of prior fragility, which is admitted as a determining factor in the production of new fractures, especially in the hip.26

In agreement with other studies, the pertrochanteric fracture was the most frequent among our patients; its incidence grows in parallel with age, in contrast to the situation with fractures located in the femoral neck.27

Although surgical delay has been decreasing over the 4 years of this study, it is still above the 48h that all the guidelines specify as the recommended limit.28 The two basic reasons for this delay were reversal of anticoagulation and/or platelet antiaggregation and the impossibility of operating on these patients at the weekend. We consider that it is important to continue working to reduce this delay, especially when due to organisational causes. The reason for attempting to reduce the delay is, as other authors have demonstrated that delay can increase mortality rate in the first year.29

A protocol for saving blood has been applied systematically in the unit by using erythrocyte-stimulation therapies and restrictive methods common in this type of units.30,31 Our blood transfusion rate was 47% of the patients for the 4 study years.

Mean stay has decreased progressively over these years. Nevertheless, the total stay (the sum of the stays in the 2 hospitals) reaches the upper limit of stays recorded in Spain, although they are not comparable because of the differences in unit design.32,33 This parameter has been burdened by the delay involved in a stay divided between 2 centres. We feel sure that it will decrease in later years after the unification of the entire process. We should point out the low rate of transfer to the convalescent unit (18.2%) compared with other series19,21,32,34 that reach up to 63%. This has evidently affected our stays negatively. There are 2 factors that may distort the indication for transfer between the units in our situation: the coexistence of acute and convalescent units in the same physical location, and the fact that it is unnecessary to change rooms or physician once the administrative procedure is processed.

Following Inouye and Charpentier's35 multifactorial delirium model, all our patients with femoral fracture presented severe factors precipitating this geriatric syndrome: trauma, surgery and anaesthesia. The presence of prior dementia in addition to these factors is key in its postoperative development.36 In our case, the incidence was 34.6%, a middle figure among those published in some series.37,38

The efficacy of rehabilitation measured with the Montebello index, although it has improved over the years, is still below the desired level and that seen in other series.39 Likewise, the functional gain on discharge that, in spite of having been considerable in more than 60% of the patients, is below the figures obtained in other series.24 The pre-fracture ability to walk (similar to that of other studies9) was fundamental for later recovery. Patients who did not require any technical aids previously recovered more quickly, regaining their initial status at 3 months. However, patients needing the help of a cane did not stop using a walker (if applicable) until 1 year post-fracture. Likewise, those that needed 2 canes, a walker or a wheel chair before the fracture continued using them at 6 months post-fracture. Both the Barthel index and the use of aids for walking before the fracture can be prognostic markers of later walking capacity.

Mortality was generally greater in the older, more ill patients, in agreement with the references consulted.21,40 In-hospital mortality (6.9%) was within the Spanish mean (5.3% for those older than 65 and 8% for those 85–89 years old), bearing in mind the mean age of our population. Considering only mortality in the OGU (3.8%), without that in the convalescent unit, OGU mortality was below the mean. Accumulated mortality at 1 year was 25%, within the published margins.41 It is notable that, over the year of follow-up, all patients who had previously needed a wheel chair or the help of another person to get around died. This group had a large number of patients who suffered from dementia, which might explain this.

LimitationsThe obligatory structural characteristics of the unit made it impossible to provide geriatric attention to the study patients in the preoperative period. Nevertheless, even though we realise that the model has limitations, we have preferred to initiate the unit with the characteristics described earlier and to attempt to obtain in the future (now achieved) complete pre- and perioperative attention. Since October 2013, the traumatology teams go to operate in the hospital Nuestra Señora de Gracia on a daily basis, avoiding the posterior hospital change for the patients; this makes comprehensive attention possible from the very beginning. We expect so sure that the study comparing the 2 series is to offer very interesting results.

All surviving discharged patients were included in the analysis of the functional results. Consequently, all those with a functional status less than total dependence (Barthel index<20) were also included. This fact is certain to have lowered the functional gain results.

ConclusionThe proximal femur fracture is so frequent and incapacitating among the geriatric population that the need for an interdisciplinary approach is undeniable. In this approach, the geriatric specialist manages the healthcare continuity and integration, with the rest of the professionals participating in decisions. The model presented had certain limitations in its inception, as well as the objective of attending to the complete process. At the time of writing this article, we have achieved total process handling (including surgery) in the OGU. We hope to improve our results and to be able to compare them with other similar units.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or on animals were carried out in this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the guidelines of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Mesa-Lampré MP, Canales-Cortés V, Castro-Vilela ME, Clerencia-Sierra M. Puesta en marcha de una unidad de ortogeriatría. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:429–438.