There are no randomized prospective studies that evaluate sports activity after total hip arthroplasty (THA). The objective of this study is to assess the level and type of sports activity in patients undergoing THA and to assess the recommendations given by physicians.

Materials and methodsWe performed a descriptive study that analyzes 46 patients (the average age was 41 years, range 37–48) under 50 years of age who underwent THA (58 hips) in our center. The average follow-up was 7.5 (1–11) years. Age, sex, sports activity according to the UCLA scale, sports activities practiced before and after the intervention, complications and recommendations given by doctors were evaluated.

ResultsThe average time to resume sport activity after the surgery was 5 (3–10) months. There were no differences in the UCLA scale before and after the operation (P > 0.05). The most practiced sport before the surgery was swimming (17%). The 31% of patients did not receive advice from their physician and the 65.2% were dissuaded from playing sports after ATC. The recommended sports were swimming (44%) and the static bicycle (17.5%), correlating with the most practiced sports after the operation.

ConclusionThe patients modified their sport activity after having undergone a total hip arthroplasty. The surgery and the physician’s advice were the ones that influenced the choice of the sports activity performed after being operated on.

No hay estudios prospectivos aleatorizados que evalúen las actividad deportiva tras una artroplastia total de cadera (ATC). El objetivo de este estudio es valorar el nivel y el tipo de actividad deportiva en pacientes intervenidos de ATC y valorar las recomendaciones dadas de los médicos.

Materiales y métodosEstudio descriptivo que analiza a 46 pacientes (edad media 41 años, rango 37−48) menores de 50 años que fueron intervenidos de ATC (58 caderas) en nuestro centro. El seguimiento medio fue 7,5 (1–11) años. Se evaluó la edad, el sexo, la actividad deportiva según la escala UCLA, las actividades deportivas practicadas antes y después de la intervención, las complicaciones y las recomendaciones dadas por los médicos.

ResultadosLa media del tiempo para retomar la actividad deportiva tras la intervención fue de 5 (3–10) meses. No hubo diferencias en la escala UCLA antes y después de la intervención (P > 0,05). El deporte más practicado antes de la intervención fue la natación (17%). El 31% de los pacientes no recibió consejos de su médico y el 65,2% fueron disuadidos de realizar deporte tras la ATC. Los deportes aconsejados fueron la natación (44%) y la bicicleta estática (17,5%), correlacionándose con los deportes más practicados tras la intervención.

ConclusiónLos pacientes modificaron su actividad deportiva tras ser intervenidos de artroplastia total de cadera siendo la propia intervención y el consejo del médico los que influyeron en la elección de la actividad deportiva realizada tras ser intervenido.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) procedures have increased in number in recent years and is increasingly common in patients under 50 years of age due to good functional outcomes, longer survival of the implants used and a low incidence of complications. The survival of the components is related to the new polyethylene designs, the quality of the materials used and multidisciplinary work between doctors and engineers. Although the main objectives of total hip prosthesis are to improve mechanical pain and decrease functional limitation,1,2 young patients demand early recovery and high functional capacity to practise sport.

Regular exercise has health benefits.3,4 Hip arthroplasty allows patients to increase their recreational and sporting activity and thus participate in health strategies. However, both the surgeon and the patient should be aware of the risks and benefits of sports activity after THA.3

Patients under the age of 50 with advanced coxarthrosis are at greater risk of early prosthetic failure. The main reason could be that a more active lifestyle is associated with aseptic loosening, polyethylene wear, peri-prosthetic fractures or prosthetic instability.5,6 For these reasons, orthopaedic surgeons often discourage patients from engaging in high-impact sports, based in many cases on personal preferences and surveys of surgeons. There are no prospective randomised studies evaluating how sports activities affect THA survival and how THA affects the ability to participate in different types of sports.

The aim of this study is to assess how THA and medical advice impact sports activities in patients under 50 years of age.

Material and methodsApproval for this retrospective study was obtained from the Regional Ethics Review Board in Pamplona, Spain. All patients gave their written consent to participate in this study after receiving oral and written information.

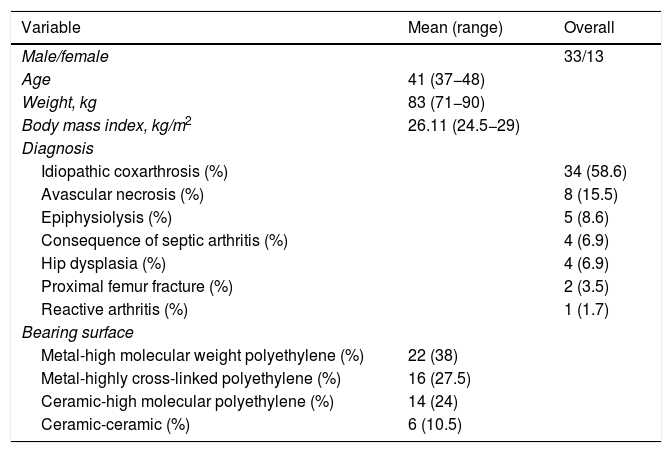

Between 2004 and 2010, 854 THAs were performed at our centre, of which 99 were under 50 years of age. We retrospectively analysed these 99 arthroplasties (78 patients). Of these 99 arthroplasties, 41 (32 patients) were excluded from the analysis due to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. As a result, 58 arthroplasties (46 patients, 33 male and 13 female) were available for analysis. The mean age was 41 years (range: 37−48 years) and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.11 kg/m2 (range: 24.5−29 kg/m2). The diagnoses that led to THA are shown in Table 1. The mean follow-up was 7.5 years (range: 1–11).

The inclusion criteria were patients aged 50 years or under, active workers without concomitant disease that could affect and limit their physical activity, and absence of other joint fractures or lower extremity arthroplasty. The exclusion criteria were THA due to a tumorous lesion, primary THA that developed acute infection in the immediate postoperative period, total knee or ankle arthroplasty, joint fractures treated with osteosynthesis and patients not followed up in our centre.

All the interventions were performed by the same surgical team and the same surgical technique was used in all cases. The approach was anterolateral, in a supine position, scope-guided and under general anaesthesia. All implants used were non-cemented. The stem used in all hips was the CLS Spotorno® (Zimmer Biomet®, Warsaw, Indiana, USA). Twenty-seven expanding cups (Zimmer Biomet®, Warsaw, Indiana, USA) and 31 Allofit® cups without screws (Zimmer Biomet®, Warsaw, Indiana, USA) were used. A metal-high molecular weight polyethylene bearing surface was used in 22 THA, metal-highly cross-linked polyethylene bearing surface was used in 16 THA, a ceramic-highly cross-linked polyethylene bearing surface was used in 14 THA and ceramic-ceramic bearing surface was used in 6 THA. The most used femoral head diameter size was 28 mm (used in 29 arthroplasties), followed by 36 mm (used in 25 arthroplasties) and finally 32 mm (used in 4 arthroplasties).

All the patients followed the same rehabilitation protocol, walking fully weight bearing at 24 h initially assisted with a walking frame and later with 2 crutches. Before discharge, patients are taught to walk up and down stairs. The crutch on the operated side of the hip is removed at 6 weeks post-surgery. The remaining crutch is removed at 8 weeks post-surgery.

All the patients underwent the same clinical and radiographic examinations. These were at 6 weeks, 3, 6 and 12 months post-surgery. Then, if no complications, every 2 years.

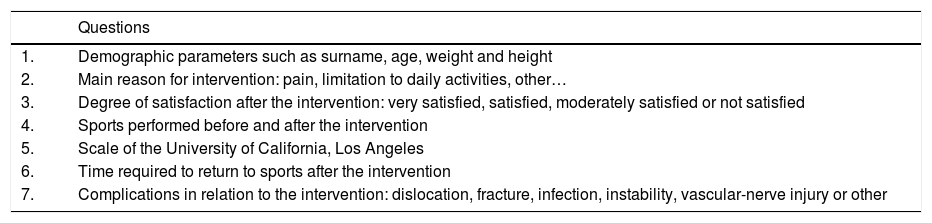

Table 1 shows the patient demographics, as well as the diagnosis leading to the THA and the prosthetic components used. To determine the sport (at the end of the follow-up) that the patient was doing at the time, we used a telephone questionnaire with each patient. The interviewer was always the same and the questionnaire included 7 questions (Table 2). The number of sports activities carried out by the patients, in isolation or combined, before and after the intervention is shown in Table 3. We did not take into account the sports carried out in the period between prostheses, in the patients who had undergone surgery on both hips in 2 stages. Level of sports activity was measured using the scale of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) before the intervention and at the end of the follow-up. The UCLA scale provides a continuous scale for level of activity, where 1 means inactivity or dependence and 10 means impact sports such as running, tennis, football, basketball or skiing. The classification by Clifford and Mallon7 was used to define impact sports in our patients.

Demographic parameters.

| Variable | Mean (range) | Overall |

|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 33/13 | |

| Age | 41 (37−48) | |

| Weight, kg | 83 (71−90) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.11 (24.5−29) | |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Idiopathic coxarthrosis (%) | 34 (58.6) | |

| Avascular necrosis (%) | 8 (15.5) | |

| Epiphysiolysis (%) | 5 (8.6) | |

| Consequence of septic arthritis (%) | 4 (6.9) | |

| Hip dysplasia (%) | 4 (6.9) | |

| Proximal femur fracture (%) | 2 (3.5) | |

| Reactive arthritis (%) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Bearing surface | ||

| Metal-high molecular weight polyethylene (%) | 22 (38) | |

| Metal-highly cross-linked polyethylene (%) | 16 (27.5) | |

| Ceramic-high molecular polyethylene (%) | 14 (24) | |

| Ceramic-ceramic (%) | 6 (10.5) | |

Number of sports activities before and after the total hip arthroplasty.

| Number of sports performed by the patient | Before the intervention (n = 46) | After the intervention (n = 46) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 12 | 10 |

| One | 9 | 13 |

| Two | 11 | 13 |

| Three | 5 | 5 |

| Four or more | 9 | 5 |

| Impact sportsa | 32 | 7 |

| UCLA (SD) | 6.85 (3.01) | 6.22 (2.24) |

SD: standard deviation; UCLA: Scale of the University of California, Los Angeles.

In the radiographic study, stem movement was evaluated as the difference, in millimetres, between the shoulder of the prosthesis and the greater trochanter. We compared this difference with those obtained during the immediate postoperative period and the following medical check-ups. Polyethylene wear was measured as the difference between the centre of the head and the lateral and medial edge of the cup. These were classified as symmetrical or asymmetrical. The area of acetabular osteolysis was classified by Charnley zones.

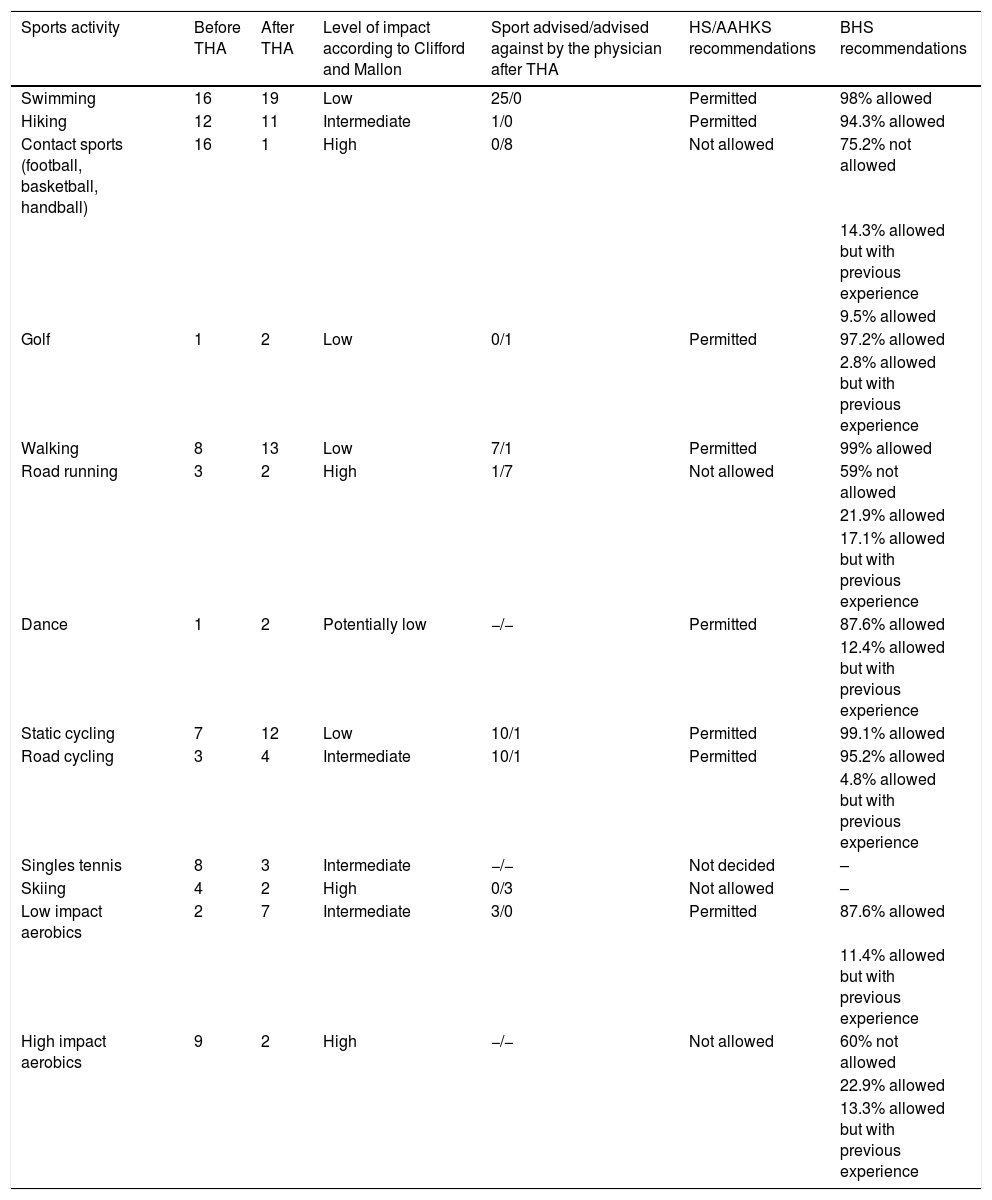

Finally, we compared the recommendations given by the doctors to our patients on practising sports, if any. We classified them according to the classification by Clifford and Mallon7 before the THA and at the end of the follow-up. In addition, we compared these recommendations with the guidelines for sports practice according to the Hip Society/American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Survey (HS/AAHKS)8 and the British Hip Society (BHS).9

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the age, weight and body mass index variables was performed and defined with the mean and range. The Wilcoxon test was performed for the UCLA scale. A p < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. We did not estimate the confidence intervals because the UCLA scale is a non-parametric parameter. All analyses were performed using Stata 14 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Version 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

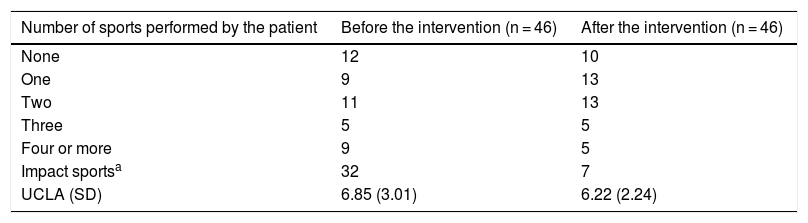

ResultsThe mean time for returning to sports activity after the intervention was 5 months (range: 3–10). There was no statistically significant difference in the UCLA scale between prior to and at the end of follow-up (p > .05). Twenty-six percent of our patients (12/46) did not engage in any type of sporting activity before the intervention. Nineteen point five percent (9/46) undertook only one type of sporting activity, and 54.5% (25/46) carried out 2 or more types of sport before the intervention (Table 3). After the intervention, 21.7% (10/46) of the patients continued with no type of sporting activity, 28.3% (13/46) performed only one type of sport and 50% 2 or more types of sports (Table 3). Table 4 summarises the types of sport performed by the patients, as well as their level of impact according to the Clifford and Mallon classification.7

| Sports activity | Before THA | After THA | Level of impact according to Clifford and Mallon | Sport advised/advised against by the physician after THA | HS/AAHKS recommendations | BHS recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swimming | 16 | 19 | Low | 25/0 | Permitted | 98% allowed |

| Hiking | 12 | 11 | Intermediate | 1/0 | Permitted | 94.3% allowed |

| Contact sports (football, basketball, handball) | 16 | 1 | High | 0/8 | Not allowed | 75.2% not allowed |

| 14.3% allowed but with previous experience | ||||||

| 9.5% allowed | ||||||

| Golf | 1 | 2 | Low | 0/1 | Permitted | 97.2% allowed |

| 2.8% allowed but with previous experience | ||||||

| Walking | 8 | 13 | Low | 7/1 | Permitted | 99% allowed |

| Road running | 3 | 2 | High | 1/7 | Not allowed | 59% not allowed |

| 21.9% allowed | ||||||

| 17.1% allowed but with previous experience | ||||||

| Dance | 1 | 2 | Potentially low | −/− | Permitted | 87.6% allowed |

| 12.4% allowed but with previous experience | ||||||

| Static cycling | 7 | 12 | Low | 10/1 | Permitted | 99.1% allowed |

| Road cycling | 3 | 4 | Intermediate | 10/1 | Permitted | 95.2% allowed |

| 4.8% allowed but with previous experience | ||||||

| Singles tennis | 8 | 3 | Intermediate | −/− | Not decided | – |

| Skiing | 4 | 2 | High | 0/3 | Not allowed | – |

| Low impact aerobics | 2 | 7 | Intermediate | 3/0 | Permitted | 87.6% allowed |

| 11.4% allowed but with previous experience | ||||||

| High impact aerobics | 9 | 2 | High | −/− | Not allowed | 60% not allowed |

| 22.9% allowed | ||||||

| 13.3% allowed but with previous experience |

Swimming and contact sports were practised most before the intervention, at 17% each. On the other hand, after the intervention, the sport most practised was swimming (23.75%), followed by daily walking (16.25%) and the exercise bike (15%) (Table 4). Contact sports decreased from 17% to 1.25% after the intervention (Table 4).

The most frequent sports, in isolation or combined, advised by the doctor were: 44% swimming, 17.5% static bicycle and 12.3% daily walking. On the other hand, the sports advised against were: 36% contact sports and 32% road running (Table 4). Of the patients, 31% did not receive advice from their doctor. On the other hand, 65.2% (30 patients) were discouraged from engaging in any sport after the THA.

Only 3 patients reported a feeling of hip instability when playing sports. With regard to sports-related complications, there was one case of hip dislocation with femoral nerve injury after trauma, and there was one case of fracture-dislocation that required a hip prosthesis replacement.

We found no case of femoral stem subsidence or aseptic mobilisation of the prosthetic components. In 9 patients minimal radiolucency was observed in Charnley zones I-II; 4 associated with asymmetric polyethylene wear. In 3 of these cases the polyethylene was replaced between 48–72 months post-surgery, and in the last case the patient was advised a polyethylene replacement, but this has not been performed to date.

DiscussionThis study shows the influence of total hip arthroplasty on sporting activity in patients under 50 years of age, and its correlation with the survival of the prosthesis. We observed that patients modified their daily sports activities following a THA. Although at the end of the follow-up the UCLA scale decreased slightly (6.85 pre-operatively; 6.22 at the end of follow-up [Table 2]) there was no statistically significant difference in sports activity. This is because the sedentary patients increased their sports activity while the more active patients reduced their activity.

Questionnaire.

| Questions | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Demographic parameters such as surname, age, weight and height |

| 2. | Main reason for intervention: pain, limitation to daily activities, other… |

| 3. | Degree of satisfaction after the intervention: very satisfied, satisfied, moderately satisfied or not satisfied |

| 4. | Sports performed before and after the intervention |

| 5. | Scale of the University of California, Los Angeles |

| 6. | Time required to return to sports after the intervention |

| 7. | Complications in relation to the intervention: dislocation, fracture, infection, instability, vascular-nerve injury or other |

Several studies have evaluated sports activity in patients under 60 years of age after THA. In these studies, sports activity, such as walking,10–13 increased after the intervention, but we did not find studies similar to ours in the literature that provide information on which sports specifically increased or decreased after the intervention. Sechriest et al.13 found a relationship between body mass index and walking after THA, with no significant differences in prosthetic component wear between the groups. In our results, after the intervention, the most practised sport was swimming (23.75%), followed by daily walking (16.25%) and static cycling (15%). Contact sports decreased from 17% to 1.25% after the intervention (Table 4).

The first recommendations on sports activity after THA were given by the HS14 in 1999. Later, in 2007, they were supplemented by the recommendations of the HS/AAHKS.8 These recommendations involved a change as THA patients began to be allowed to start playing sports that were not allowed or conditions were placed if they were to be allowed. Four sports were changed from “not decided” to “allowed” (daily walking, cross-country skiing, rowing and dancing). Three sports changed from “not decided” to “allowed but with previous experience” (downhill skiing, weightlifting, ice skating/rollerblading). One sport changed from “not allowed” to “not defined” (singles tennis) and four sports changed from “allowed but with previous experience” to “allowed” (hiking, bowling, road cycling and low impact aerobics). On the other hand, 6 sports activities, not described above, were included in the recommendations. Three were included in the “allowed” group (climbing, walking/running on a treadmill and elliptical), one was included in the “allowed but with previous experience” group (Pilates), one was included in the “not allowed” group (snowboarding) and one was included in the “not decided” group (martial arts).8

The 2007 recommendations8 were in force until 2017 when they were again updated with the BHS9 recommendations. The latter recommendations were established through a survey of different specialists, preferably in THA. We observed discrepancies in high-impact sports activities (high-impact aerobics, contact sports or road running) between the 2007 recommendations8 and the 2007 recommendations.9 The 2007 recommendations8 do not allow any contact sports after the intervention. However, according to the 20179 recommendations 39% of surgeons surveyed would allow patients to run, 36.2% would allow high-impact aerobic exercise and 23.8% would allow contact sports (Table 4). For this reason, we recommend individual patient study, since in our results we have observed that doctors only recommended low-impact sports (swimming, daily walking or cycling) and discouraged, regardless of patient preference, sports with greater impact on the hip. In summary, current guidelines allow contact sports if the patient has previous experience (Table 4). We should not recommend contact sports to patients if they have not practised this type of sport before the operation.

The risk of dislocation of a primary THA is 1%–4% in the general population.1 Seyler et al.15 noted that the failure or surgical revision rate was not as high in THA patients who played tennis as in THA patients who did not play tennis. In our study only 3 patients continued to play tennis after the operation (Table 4), therefore we cannot corroborate the results of Seyler et al.15

In recent years, the ceramic-highly cross-linked polyethylene and ceramic-ceramic bearing surface seems to have good results.16–18 However, they have been associated with squeaking17,19 or failure during sporting activity, 17 although the development of new ceramics and designs has also reduced these problems.

Expanding cups raise concerns about the optimal stability of the polyethylene liner and the possibility of long-term implant rupture in young patients. In our series, 27 arthroplasties with expanding cups were collected, this is because it was in 2009 that the Allofit cup was introduced in our centre. In addition, our patients did not have problems with the expanding cup, but with the type of polyethylene. Currently, we use Allofit cups in young patients; the expanding cups could be used, even though they have less stability and may have a higher breakage rate. We observed higher rates of osteolysis (9 out of 48 patients) or early loosening and replacement of polyethylene (3 out of 4) in THAs with previous generation polyethylene (high molecular weight polyethylene) compared to current materials (highly cross-linked polyethylene).

In all the patients who had polyethylene wear, we used an expanding cup, high molecular weight polyethylene, 28 mm head and Spotorno stem. With regard to the sports activity of the three patients who underwent polyethylene replacement, two walked an hour daily and did static cycling three times a week, and the remaining patient played golf. On the other hand, the patient who presented polyethylene wear and tear and not replaced to date, cycled. Of these 4 patients it appears that sporting activity has not influenced polyethylene wear, as it is considered low or intermediate impact7 and is an allowed sport according to the HS/AAHKS8 and BHS9 recommendations.

This study is not free from limitations: (1) the number of patients included is small; (2) retrospective evaluation may increase amnestic bias; (3) the UCLA scale describes the level of sports activity in terms of a patient's functional capacity, but it is not sensitive enough to detect variability in the frequency or intensity of sports activity; and (4) we cannot know the behaviour of prosthetic components at more than 10 years of follow-up because our patients are generally followed up for less than 10 years.

ConclusionThe patients modified their sports activity after THA surgery, with the surgery itself and the doctor’s advice influencing their choice of sports activity.

It is possible for patients who have undergone total hip arthroplasty to engage in impact sports, provided they have previous experience in the sport. Individualised study of the patient is mandatory and is the key to safe sports activity after placement of a total hip prosthesis.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Payo-Ollero J, Alcalde R, Valentí A, Valentí JR, Lamo de Espinosa JM. Influencia de la artroplastia total de cadera y el consejo médico en la actividad deportiva realizada después de la intervención. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:251–257.