Thoracoscopic micro-discectomy is a treatment option for thoracic disc disease that combines the advantages of the anterior approach and the benefits of a minimally invasive technique. Adding a navigation system provides many advantages to the usual technique, as it allows accurate marking of the lesion level, improvement in the surgical approach, and precise control of herniated disc resection and vertebral osteotomy. The navigation system also reduces the learning curve for thoracoscopic technique. We report our experience in the treatment of thoracic disc herniation with image-guided thoracoscopy.

La discectomía toracoscópica es una técnica quirúrgica que combina las ventajas del abordaje anterior a la columna torácica con los beneficios de una técnica mínimamente invasiva. La adición del sistema de navegación aporta múltiples ventajas a la técnica habitual como marcaje exacto del nivel lesional, mejoría del abordaje quirúrgico, control de la resección herniaria y de la osteotomía vertebral. El sistema de navegación también acorta la curva de aprendizaje de la toracoscopia. Se presenta nuestra experiencia en el tratamiento de hernias discales torácicas mediante toracoscopia navegada.

The estimated incidence of symptomatic thoracic herniated disc is 1/1,000,000 cases in the general population,1,2 although there are publications that insinuate that the incidence is quite a bit higher.3 It affects men between the 4th and 5th decades of life with greater frequency.2 It is most frequently found below T8, probably due to a greater mobility of the thoracic spine in comparison to the rigidity of the rest of the thoracic segments.2,4

The thoracic herniated disc has been reported in relationship to pain, weakness in the lower limbs or sensitivity alterations, symptoms of radiculopathy and myelopathy, and even atypical symptoms such as gastrointestinal or cardiopulmonary ones. The symptomatology often does not coincide with the level of the hernia, which usually delays diagnosis.4 In cases with occupation of more than 50% of the spinal canal or calcification of the hernia, the degree of the symptoms is usually greater.5

The indication for surgery is rare and is established when there are radicular symptoms resistant to the standard conservative treatment or myelopathy. Surgery on the thoracic herniated disc has been estimated to be 0.5–4% a year of all surgical procedures on herniated discs.2,4

Thoracoscopic discectomy as a treatment for symptomatic thoracic hernias is a technique that combines better visualisation of the hernia through the anterior approach with the advantages of the low invasiveness involved in endoscopy (less postoperative pain, less bleeding and more prompt recovery). The use of thoracoscopy has proven the reduction of postoperative complications, mainly pulmonary problems and infections, in comparison with the open thoracotomy.3,5–7

As disadvantages involved with the technique, the most notable are the difficulty in locating and confirming the level of the lesion during the operation, the need for longer surgical time compared with the anterior or posterior-lateral open approach, and its long learning curve.3,5,6,8

The addition of a navigation system to the standard thoracoscopic technique yields many advantages: precise marking of the lesion level, improved approach and control of the hernia resection and the vertebral osteotomy. In addition, it provides the surgeon with exact information about the position of the manipulative material, reducing the margin of error and shortening the learning curve.9

We present our experience with this surgical technique and a brief discussion based on the literature published with respect to it.

Material and methodTwo cases of thoracic herniated disc operated using thoracoscopic discectomy with the help of a navigation system (O-Arm with Stealth Navigation Medtronic®) are presented. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are valuable tools for surgical planning, given that they determine the side and level of the hernia, whether it is calcified or in an intradural situation, and the degree of occupation of the canal.

In all of the operations, monitoring was used via somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs).

Surgical techniqueSelective intubation that makes it possible to collapse the lung on the side of the approach is required for this technique.

The side for the approach depends on the position of the hernia and the large vessels. The patient is placed in a lateral recumbent position with the side selected for the approach upwards. If the segment to handle is located above T6, it is usually necessary to place the arm up above the head, which makes it possible to move the scapula out of the operating field and gives better visualisation of the intercostals spaces. It is very important for the patient to be kept stable on the operating table because, if not, any change in posture can lead to navigation errors during the surgery. It is necessary to fasten the patient to the table at the hip level with Tensoplast adhesive tape, and to maintain the thorax using a support in the anterior area and another in the posterior.

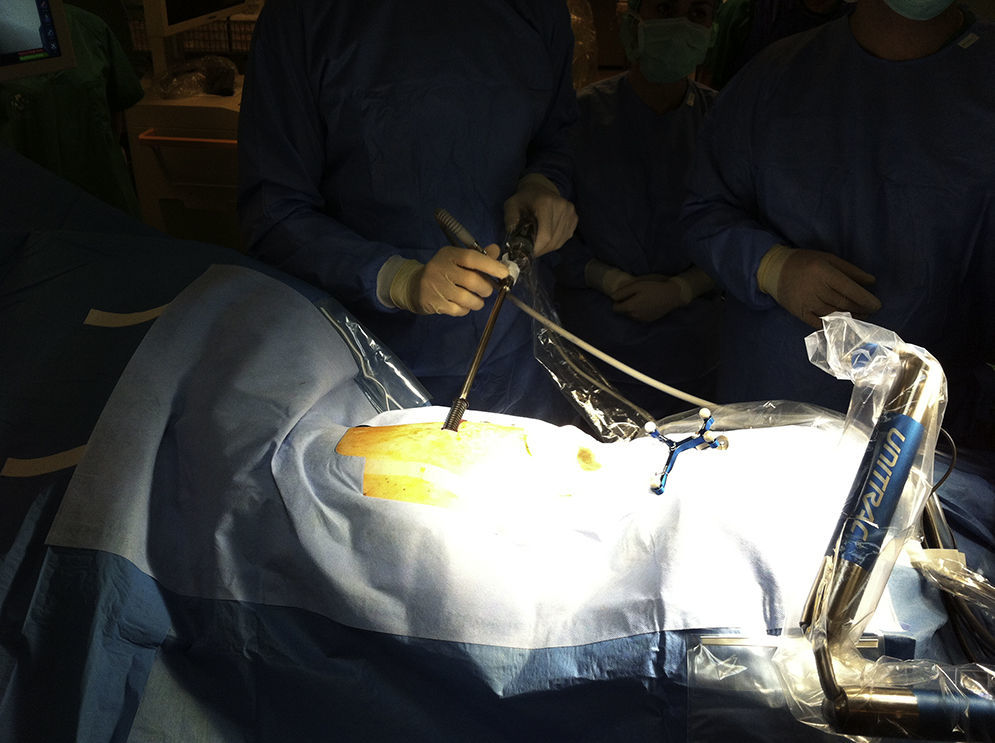

The navigation system needs an intraosseous reference probe fastened to the iliac blade or spinous process. To make it less invasive, only the skin can be closed with sutures, as was done in the two cases that we present. At the level of the iliac blade, the skin is sutured in the caudal area of the surgical field; this is done because it is easier than fixation in the spinous process when the patient is in the lateral recumbent position (Fig. 1). The receptor is placed at the patient's feet in an elevated position so that it can capture the probe signal.

In spite of the use of the navigator, it is a good idea to make a prior marking using an intramuscular needle placed above the rib over the intervertebral level. Marking is performed using the O-Arm as a fluoroscope, being careful not to penetrate the thoracic cavity with the needle.

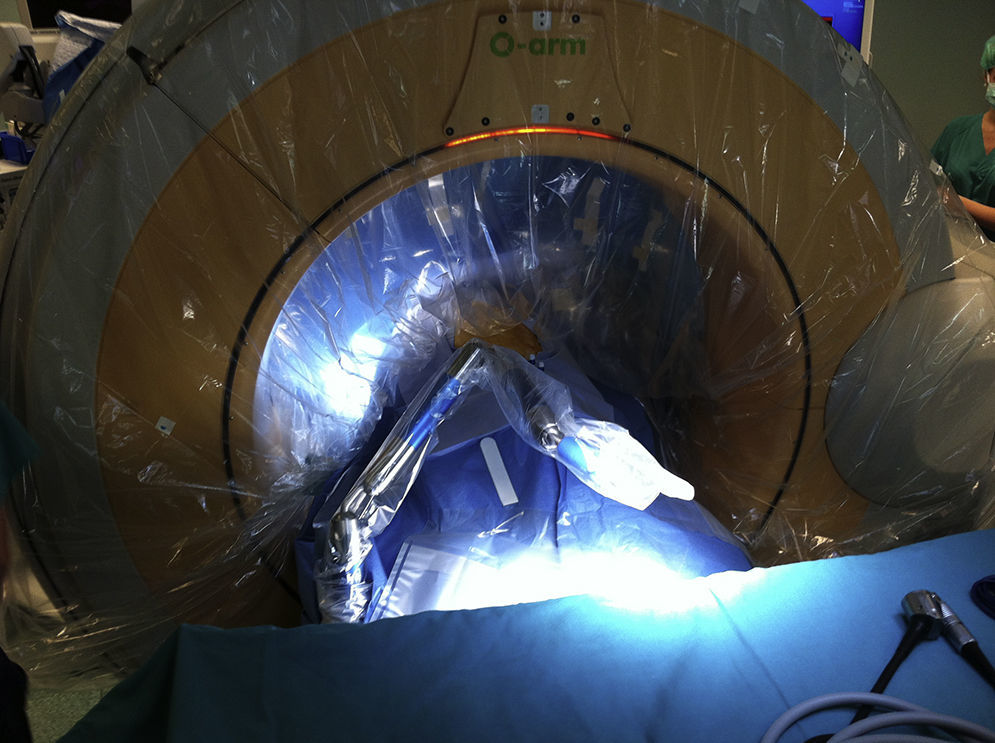

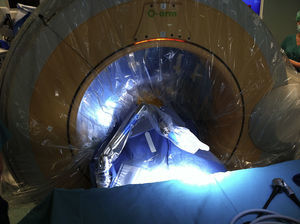

The navigation system takes an initial CT made by the O-Arm before beginning the surgery as a base. An important step before beginning the surgery is to check that the location of the hernia on the CT coincides with the fluoroscope-performed marking; this is necessary because error in the surgery level is one of the most frequent technical failures

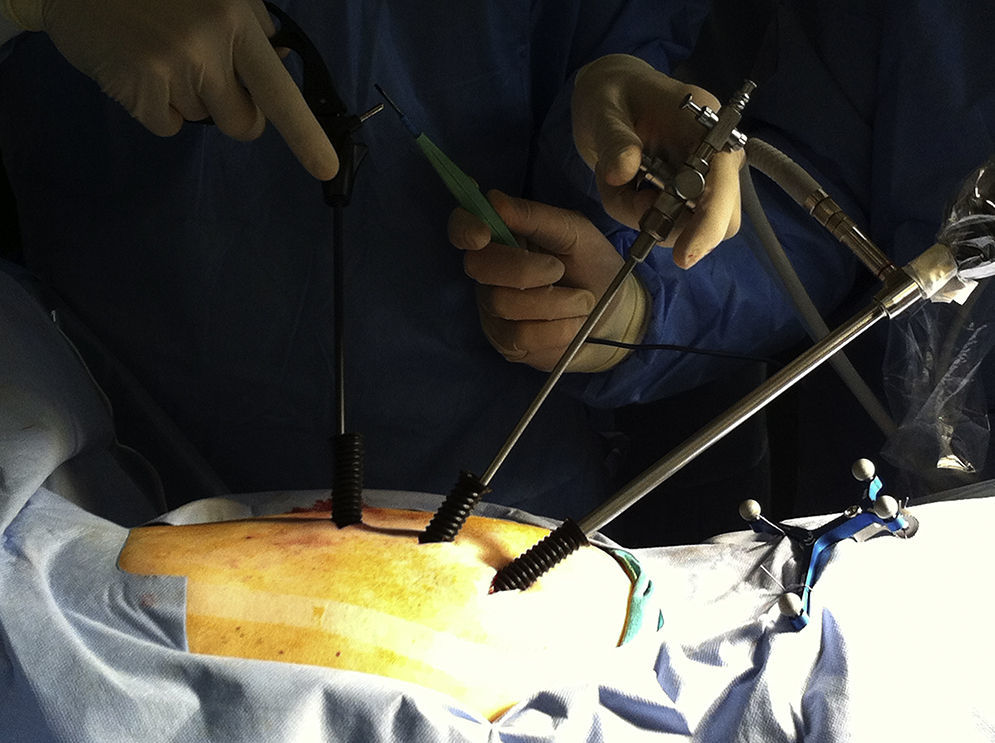

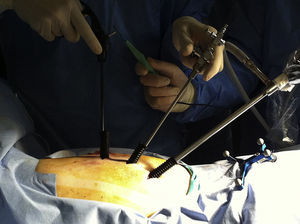

The approach normally involves 3 or 4 portals. Portal 1 is located in the anterior axillary line, at the level of the marking needs. Through this portal, the camera is inserted with the lung collapsed to carry out the exploratory thoracoscopy that confirms the absence of pleural adhesions and varieties of venous plexus of the azygos, which could make the surgery more difficult or impossible. The camera is held stable through a system of camera support fixed to a pneumatic arm anchored to the operating table (Unitrack, Aesculap), which makes it possible to correct its position quickly during the surgery (Fig. 2). Portals 2 and 3 are used for the aspirator and other work instrument, respectively (Fig. 3). The decision as to whether to place Portal 4 depends on the need to separate the lung if it is insufficiently collapsed, or on the caudal levels for separation of the diaphragm.

The partial corpectomy of the posterolateral wall is performed through the work portals using a high-speed drill. The navigator allows us to check the direction and depth of the vertebrectomy at all times, and helps to plan the amount of osseous resection. The fact that a more precise, directed osseous resection can be carried out helps to control bleeding from the epidural venous plexus. The hernia is the resected and bleeding is controlled by means of bipolar coagulation and haemostatic agents.

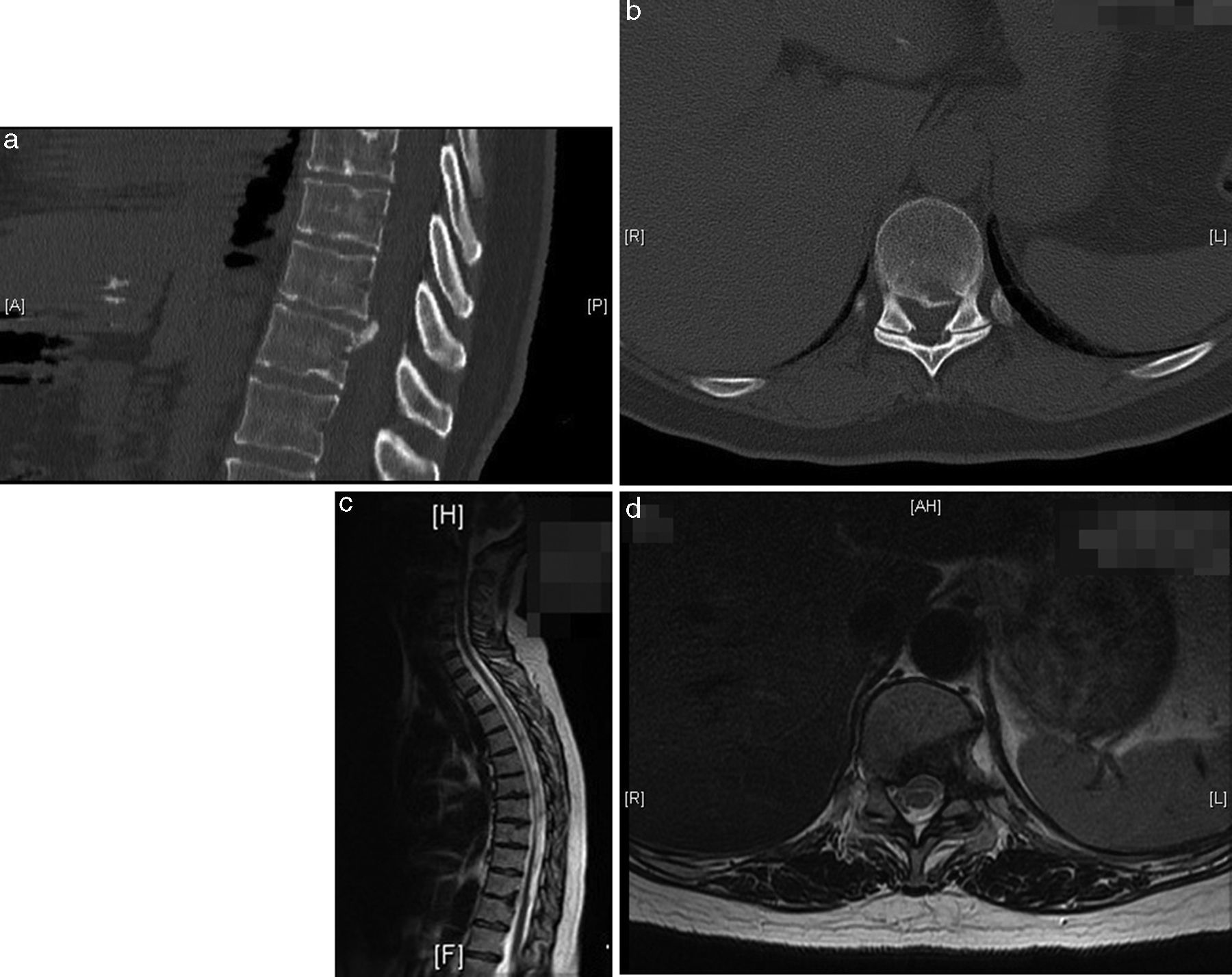

At the end of the intervention, a second intraoperative CT is used to confirm that the resection has been complete (Fig. 4). The instruments are removed from the portals and a pleural drainage is left. If the drainage is unproductive, it can be removed immediately; if there is an air leak via pleural fistula, the drainage should be kept for at least 48h.

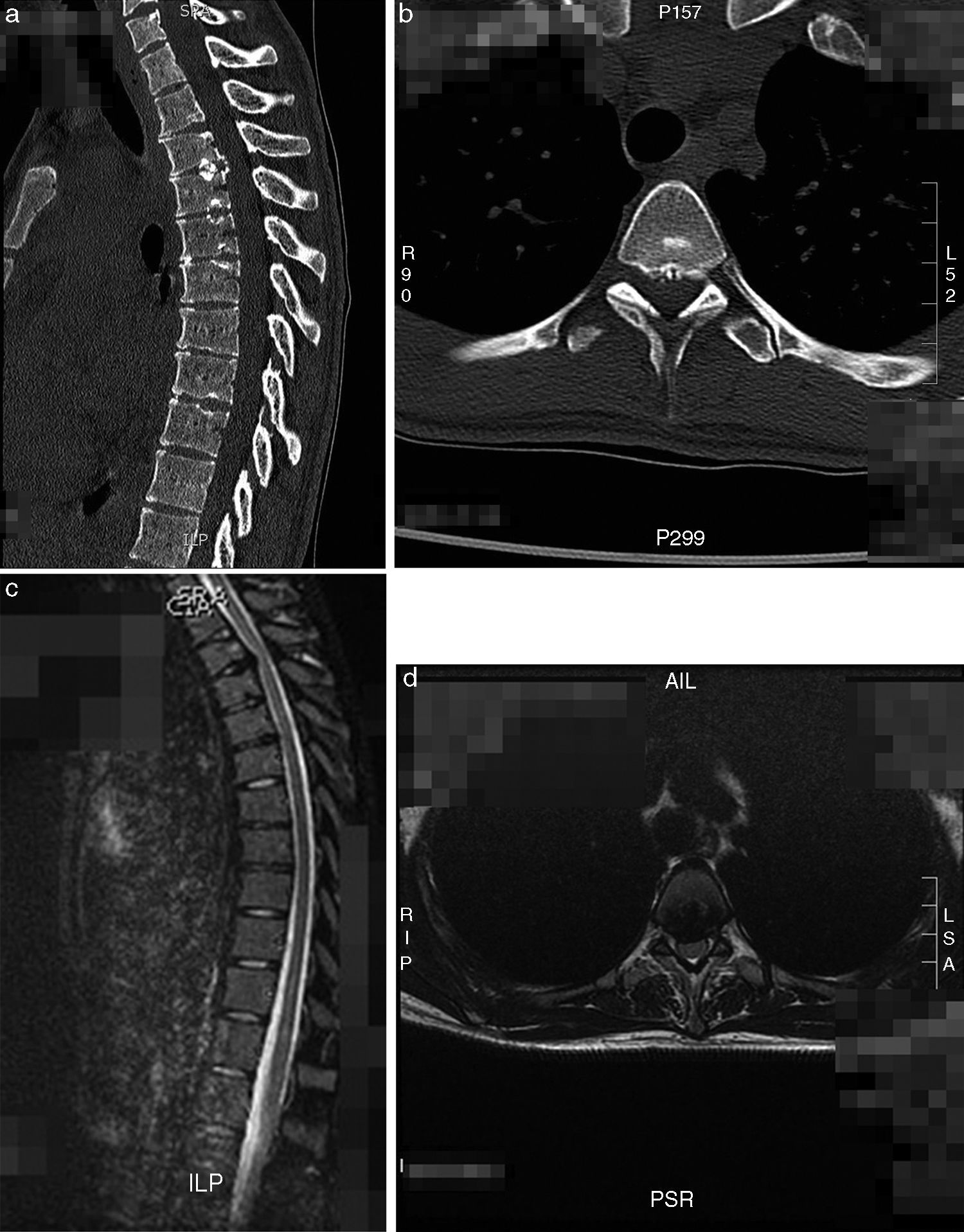

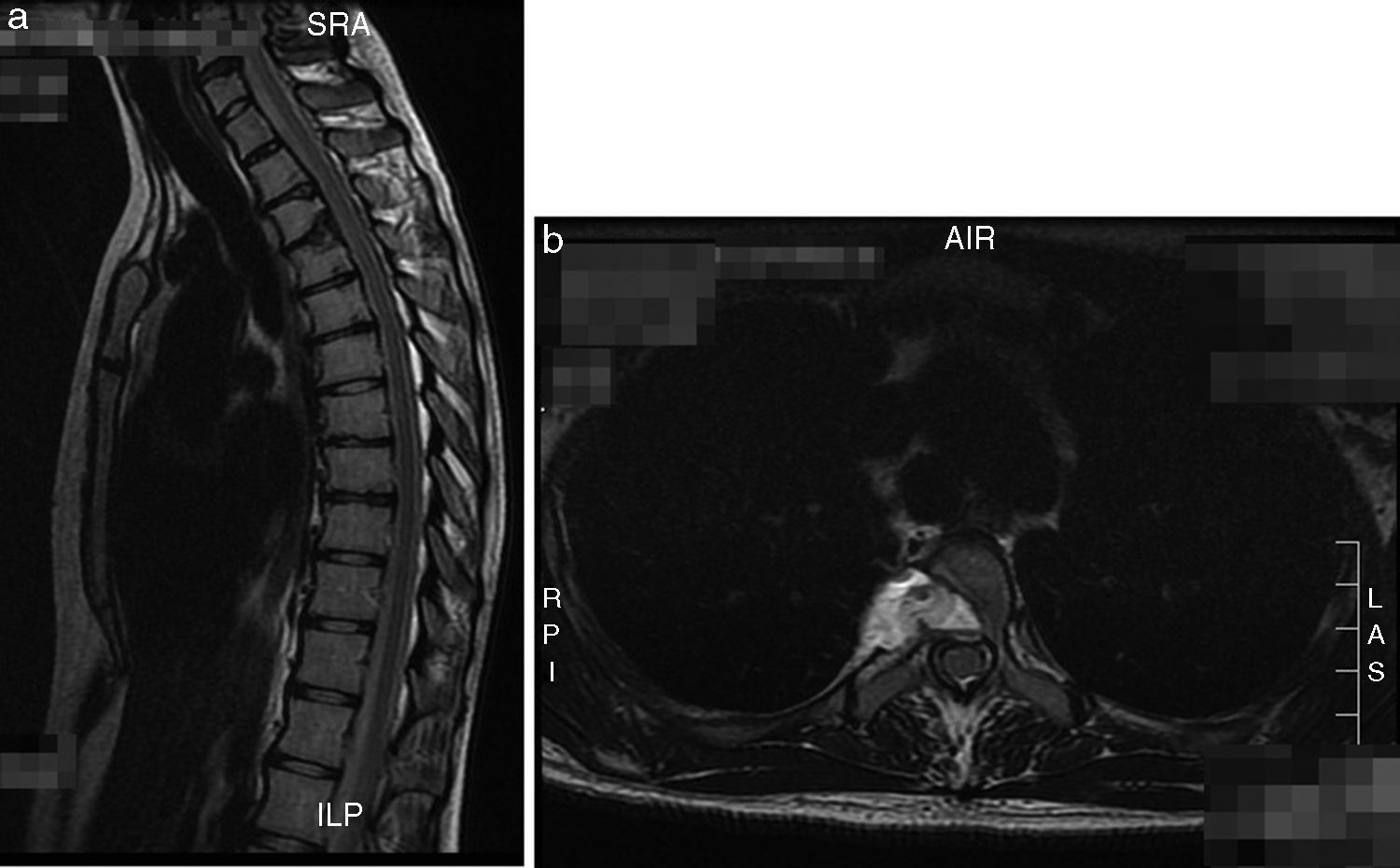

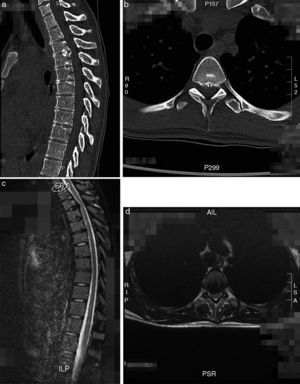

Clinical case 1A 22-year-old woman that reported sensation of loss of strength, dysesthesias in lower limbs and intercostal pain of neuropathic characteristics Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) 6. Upon examination, loss of strength 4/5 was found in the left quadriceps, along with slight hyperreflexia in that limb. A partially calcified T3–T4 hernia was seen on the preparatory CT and MRI (Fig. 5a–d). Thoracoscopic resection was performed with the help of the navigator, using 3 portals. Surgical time was 320min and bleeding, 750ml. The patient improved the preoperative clinical picture after the operation, with a postoperative VAS of 2 during follow-up. The post-resection control image is shown in Fig. 6a and b.

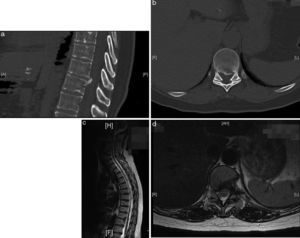

Clinical case 2A 64-year-old woman referred from another centre with the diagnosis of T10–T11 hernia. The patient reported the sensation of electrical discharges in both legs, instability when walking and VAS 7 pain in left hemithorax of months of evolution; urinary incontinence had recently been added to these. The choice was again made for thoracoscopic resection of the hernia with the help of the image-guided navigator; in this case, a 4th portal was used to help separate the diaphragm. Surgical time was 260min and bleeding, 600ml. After the surgery, the patient's VAS became 2 points. The postoperative control image is shown in Fig. 7a–d.

ComplicationsThe most frequent postoperative complication that we saw was pain in the hemithorax of the approach that increased with deep breaths and with cough. In both cases, the pain resolved completely with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in fewer than 4 weeks. The pleural drainage was retired in both cases in 48h without complications. There were no neurological complications, postsurgical infection, inadvertent opening of dura or cerebrospinal fluid fistula in the cases presented.

DiscussionThoracoscopic discectomy makes complete resection of thoracic hernias possible. It has been evaluated in several studies since its first report in 1994.8 All those studies coincide in concluding that it is an effective, minimally-invasive technique that obtains good clinical results, with it even being cited in several publications as the surgical technique of choice.2,3,6,7

As has been commented, in the presence of a calcified hernia, the symptomatology is usually greater, so the indication of surgery is likewise greater.6,7 Consequently, there is an elevated percent of calcified hernias operated in most of the surgical series published.

There is some disagreement as to whether thoracoscopic discectomy is a safe technique in the treatment of calcified thoracic hernias. Some authors recommend using the thoracoscopic technique principally in the case of non-calcified hernias, recommending an open approach in the case of extensive calcified hernias.6 However, in a prospective study of hernias of widely varied origin, the usefulness and safety of the thoracoscopic technique has been found, even in cases of very large calcified hernias with occupation of the canal above 50%.7 In the first case presented, the hernia was calcified and was completely resected without any complications. The navigation system with intraoperative CAT is of great help to confirm complete resection in the case of calcified hernias, given that a frequent error during surgery is to confuse them with the posterior wall of the vertebral body, leaving a remnant of hernia that has the potential to maintain pressure on the neural structures.

The use of thoracoscopy has demonstrated the reduction of postoperative complications, mainly those of pulmonary problems, intercostal neuralgias and infections, compared with open thoracotomies.3,5–7 In our experience, the most frequent postoperative complication with this technique is pain in hemithorax that goes away after 3–4 weeks of inflammatory treatment. It is difficult to tell whether this pain is a true intercostal neuralgia or pain due to the surgical approach.

Adding the navigation system to the normal thoracoscopy lends many advantages to the surgical technique.9

The use of navigation reduces the risk of error in the level of the intervention, given that it permits intraoperative visualisation of the lesion and placement of a single intrathoracic needle visible with the endoscopic camera that marks the exact level on which to intervene. This system reduces the risk of marking error with respect to other systems such as rib counting. Likewise, it reduces the risk of lesions of the intercostal vessels or lung tissue if several intrathoracic marking needles are placed in the case of high thoracic hernias.

The navigation system makes it possible to check the depth of osseous resection continuously during corpectomy and reports information about the distance of separation from the spinal cord, which helps to reduce the risk of neurological injury, control bleeding and assess the need for vertebral stabilisation after the hernia resection. The anatomical information that it provides helps surgeons to situate themselves better, which ensures a highly precise approach and facilitates opening a work window that respects the segmental vessels and the sympathetic chain; consequently, it reduces potential complications of the technique. All of this contributes to improving the safety of the thoracoscopic technique and shortening the learning curve. It also makes it possible to carry out intraoperative controls to verify that the hernia resection is complete, which is important given that incomplete resection of the hernia is a frequent technical error.10

Thoracoscopy is a demanding surgical technique that has a long learning curve; however, once this period is overcome, the surgical times are comparables with those of open surgery.3,5–7 Although using the navigator increases the surgery preparation time before beginning the operation, the better orientation of the surgeon may compensate throughout the intervention for this loss of time.

Other disadvantages are how expensive the navigation systems with intraoperative CAT are and the possibility of technical failure of the navigation system if the reference marks are moved. For that reason, it is recommended that the intraosseous reference probe should be correctly attached and that the information the navigation system provides should be confirmed with the anatomical references visible during the thoracoscopy.

ConclusionThoracoscopic discectomy is a safe, effective method of treating soft and calcified thoracic hernias. Image-guided navigation adds a tool to the thoracoscopy that makes better intraoperative orientation possible, which may improve the safety of the technique and shorten the learning curve and the net surgical time. Noteworthy drawbacks are the increased time in surgery preparation before beginning the operation and the elevated cost of the navigation system.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or on animals have been performed for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bordon G, Burguet Girona S. Tratamiento de la hernia discal torácica mediante toracoscopia navegada. Nuestra experiencia. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:124–129.