We report the case of a paediatric patient who presented at the Emergency Department with severe pain in the right lower extremity caused by a scorpion sting. Analgesics were ineffective, so we decided to perform an ultrasound-guided popliteal block, which provided complete analgesia and allowed the patient to be followed up in the outpatient department, with no adverse effects. The sting of the species of scorpion found in Spain is not dangerous to human life; however, it causes self-limiting localised pain that lasts for 24−48h, and can be severe. The first-line treatment is effective analgesia. Regional anaesthesia techniques are useful in the control of acute pain, and are an example of effective collaboration between the Anaesthesiology and Emergency services.

Presentamos el caso de un paciente pediátrico que acudió a Urgencias con dolor severo en la extremidad inferior derecha causado por la picadura de un escorpión. Ante la ausencia de respuesta a los analgésicos administrados, se optó por realizar un bloqueo poplíteo ecoguiado, lo que consiguió una analgesia completa y permitió el manejo ambulatorio del paciente, sin referir efectos adversos. Las familias de escorpiones presentes en nuestro país no suponen un riesgo vital para el ser humano, pero su picadura produce una reacción local con dolor autolimitado a unas 24−48h que puede ser severo. El manejo prioritario es realizar una correcta analgesia. Las técnicas anestésicas regionales son de utilidad para el control del dolor agudo y pueden representar una colaboración eficaz entre los servicios de Anestesiología y Urgencias.

The management of refractory acute pain falls within the remit of the anaesthesiologist, and therefore these specialists are often asked to work together with specialists from other hospital departments. Some particularly rare situations can be challenging, and in this report we describe the case of a child presenting with a scorpion sting that caused acute, high intensity pain that responded poorly to most analgesics administered. We decided to perform a sciatic nerve block, which provided excellent pain relief and allowed the patient to be discharged home within a few hours. It is important to bear in mind that regional anaesthesia techniques are part of our arsenal for the non-surgical treatment of acute pain.

Case reportOur patient was an 11-year-old boy weighing 32kg with a history of hypothyroidism under treatment with levothyroxine and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder monitored by Psychiatry. He was admitted to the Emergency Department of our Hospital for a scorpion sting on the head of the first metatarsal of the sole of the left foot. He had been stung some 2h previously, and had initially been treated in Primary Care with paracetamol, subcutaneous injection of 2% mepivacaine, prednisolone 0.5mg/kg, and intravenous dexchlorpheniramine, all of which were ineffective. Upon presentation at the Emergency Department, the attending doctors first ruled out life-threatening warning signs and contacted the National Institute of Toxicology. Following this, they contacted the Anaesthesiology Department to request acute pain management. On arrival, the patient was crying and in considerable emotional distress, describing symptoms of intense, constant lancing pain and frequent episodes of poorly tolerated exacerbations, which he rated 10 on the visual analogue scale (VAS). We administered IV meperidine 1mg/kg and metamizole for immediate pain management, which achieved partial relief (VAS 7). However, given the intensity of the pain, which was expected to last for around 48h, we decided to perform popliteal sciatic nerve block in order to expedite discharge home. Under aseptic conditions and monitoring, and after the patient had been premedicated with 1.5mg IV midazolam, we performed an ultrasound-guided popliteal sciatic nerve block using an AKUS TM peripheral nerve block needle (22G 50mm). The needle was inserted in plane under ultrasound guidance with a linear transducer and sterile technique, and positioning was confirmed using neurostimulation. Then, 12ml of 0.5% L-bupivacaine, 6ml of 2% lidocaine, 8mg dexamethasone, and 2ml bicarbonate 1M (total 22ml) were administered without incident. Complete sensory and motor blockade with complete resolution of symptoms (VAS 0) was confirmed at 45min. After verifying oral tolerance, the patient was discharged home, and was followed up daily by telephone to monitor his course. He reported prolonged sensory and motor block, with partial recovery of sensation 36h after nerve block, and total recovery within 48h. There were no adverse effects and no analgesic rescue was required after discharge.

DiscussionIn Europe, scorpion stings are a relatively rare phenomenon,1 given the predominantly urban population. They occur mainly in rural areas during the summer, which is when these animals are active, and usually involve the extremities, which are frequently uncovered. In Spain, scorpions from the Buthidae and Euscorpiidae2 families, which are the most prevalent, are responsible for most stings. Their venom is not life-threatening, and usually causes local disturbances in the form of severe pain, swelling, and oedema lasting for around 48h.1,2 Rarer manifestations include systemic symptoms, such as muscle cramps, fasciculations, hypoesthesia or paraesthesia. These symptoms are more common in children, due to their low body weight.1 There is no evidence of risk to the foetus in pregnant women with scorpion stings.3 Nevertheless, in Spain there is always the remote possibility of a sting being caused by an exotic, highly venomous species imported from another county, but this is beyond the scope of this report.

For all the above reasons, the first line of treatment is analgesia, because the pain triggered by neurotoxins present in the venom4 can be disabling and refractory to conventional analgesics. It is important to use a multimodal approach tailored to individual characteristics. Patients will usually have presented to a hospital Emergency Department or a Primary Care centre, and will therefore be treated on an outpatient basis, so although it would be possible to design a strategy based on third-step analgesia plus adjuvants, such as gabapentinoides, we suggest using regional anaesthesia as an effective, low risk management strategy, provided it is performed under certain conditions. This approach is particularly suitable, given the self-limiting nature of this pain.

Regional anaesthesia techniques have progressed considerably in recent decades following the introduction of various new anaesthetic agents (including enantiomeric forms of traditional anaesthetics, such as levo-bupivacaine) and, above all, the introduction of ultrasound in the routine practice of anaesthesiologists. Several recent studies have shown that administering ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve blocks in the Emergency Department for the treatment of acute pain caused by fractures and trauma in paediatric patients reduces the need for opioids.5,6 In this case report, ultrasound-guided popliteal sciatic nerve block was safe and provided effective control of acute pain caused by a scorpion sting in a paediatric patient. This is a rare though highly interesting indication for this technique, as it achieved good pain control without the need for hospitalisation. Anaesthesiologists must be familiar with regional anaesthesia techniques and their indications, and must take follow-up measures such as informing the patient, their family, and the treating physician of the duration of the blockade and possible adverse effects to look out for. The type of potential side effect will depend mainly on the site of the nerve block,7 and the risk will be reduced with the use of ultrasound.8

In this case, we were asked by the paediatrician on duty to help treat a highly distressed child presenting with intense neuropathic pain rated 10 on the VAS, in whom conventional analgesics had not been effective. We initially decided to administer a major opioid (meperidine) that is associated with less risk of respiratory depression than other options (fentanyl, for example). But this only achieved partial control (VAS 7). Given the failure of all previous strategies, and the risk of hospital admission, we then decided to perform a regional nerve block.

As the site of the sting was slightly posterior to the head of the first metatarsal, an area that would be only partially covered by an interdigital nerve block, and given the ineffectiveness of subcutaneous mepivacaine administered in Primary Care, we decided to perform popliteal sciatic nerve block. Because of its proven safety and low risk of complications, this block is ideal for Emergency Department treatment of acute pain in the paediatric population.9 Performing the block under ultrasound guidance allowed us to administer nearly the maximum dose of anaesthetic (thus prolonging the analgesic effect) and to visualize the spread around the sciatic nerve, hence avoiding intravascular or intramuscular extravasation. Nevertheless, the lowest possible dose should be used, and in this respect some researchers have reported that using clonidine as an adjuvant to local anaesthetics in paediatric patients allows the practitioner to reduce the dose administered and the associated motor blockade.10–12 The patient was kept under observation for 90min after performing the nerve block. The effect of the blockade was progressive, and within 45min local neuromuscular blockade was complete and the symptoms had resolved. At the end of the observation period, the patient was able to eat soft food, and he was discharged home once adverse events had been ruled out and the parents had received instructions on his post-discharge care and the duration of the analgesia. Analgesic treatment at discharge consisted of paracetamol (100mg/ml suspension: 4.8ml every 6−8h) and metamizole (500mg/ml suspension: 1.5ml every 4h) for rescue analgesia. The patient did not require metamizole. The parents were told to return to the ER and speak to an on-duty anaesthesiologist if the patient complained of pain or an adverse effect.

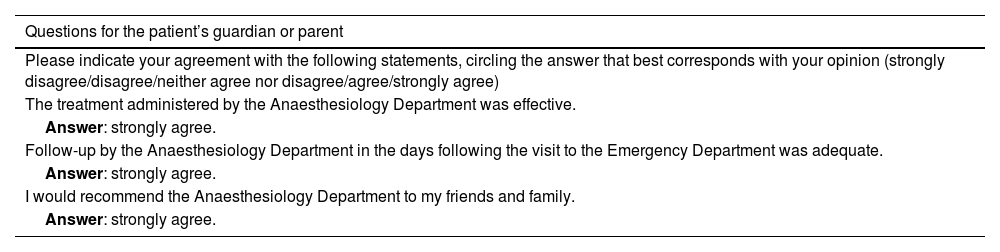

Staff from the Anaesthesiology Department contacted the parents daily by telephone for 3 days after the nerve block to enquire after any clinical symptoms and evaluate signs of adverse effects. Three months later, the parents were contacted again for further follow-up, and denied any adverse effects. We believe it is important to report this case for two reasons: first, nerve block was performed in an emergency situation in a patient who had not been previously seen in the Anaesthesiology Department and had not received the information and health education usually provided by the anaesthesiology nurse. Secondly, the block was performed in the Emergency Department, which is a rare setting for this type of treatment. We gave the family a questionnaire and asked them to rate their satisfaction with the treatment received by our Anaesthesia Department (Table 1).

Satisfaction questionnaire.

| Questions for the patient’s guardian or parent |

|---|

| Please indicate your agreement with the following statements, circling the answer that best corresponds with your opinion (strongly disagree/disagree/neither agree nor disagree/agree/strongly agree) |

| The treatment administered by the Anaesthesiology Department was effective. |

| Answer: strongly agree. |

| Follow-up by the Anaesthesiology Department in the days following the visit to the Emergency Department was adequate. |

| Answer: strongly agree. |

| I would recommend the Anaesthesiology Department to my friends and family. |

| Answer: strongly agree. |

The take-away messages in this case are: Scorpion stings, though rare, can occur in Spain. The first line of treatment in these cases is analgesia, because the neurotoxins present in the venom produce extremely intense inflammatory neuropathic pain that does not respond well to conventional analgesics. Because of the foregoing and the transitory nature of the pain (usually lasting 48h), these patients are candidates for regional anaesthesia. As anaesthesiologists, these techniques are part of our therapeutic arsenal, and allow us to play a pivotal role in the management of acute pain not only in the surgical context, but also in patients seen in other hospital departments.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.