Most of the international bibliography published on Covid-19 pandemics is focused in the Asian, European or American continents. It seems that incidence is lower in Africa. In this article we hypothetize on several of the possible causes sustaining these differences. Population pyramid, climate, african population own vulnerability/resistance or sociopolitical factors are underlined.

In the case the pandemics will spread in Africa, the lack of basic healthcare resources will perhaps make the consequences disastrous and of a dantesque magnitude.

La mayoría de la bibliografía mundial sobre la pandemia Covid-19 se ha focalizado en los países del continente asiático, europeo o americano. En África parece que la incidencia es menor. En este artículo se hipotetiza sobre alguna de las posibles causas que han dado lugar a estas diferencias. La pirámide poblacional, la temperatura ambiente, la vulnerabilidad/resistencia de los habitantes del continente o factores sociopolíticos son subrayados.

En caso de que la pandemia se extendiera en el continente africano, posiblemente la falta de recursos sanitarios haría que las consecuencias fueran desastrosas y de una magnitud dantesca.

I have been living in Kinshasa (DR Congo) since last June, working as an anaesthesiologist and operating room manager at Monkole Hospital. Some people have asked me why there are far fewer cases of coronavirus and a much lower mortality rate in Africa. There is no evidence-based answer to this question, but I think there are several factors involved.

The differences between the development of the Covid-19 epidemic in Europe compared to Africa are clear and striking. While the number of fatalities in the United Kingdom, Italy, France and Spain exceed 20,000 cases per country, African states such as DR Congo have only reported 32 deaths from the virus, and the rate in most other African countries is similar. In my opinion, there are 4 factors that could explain these differences.

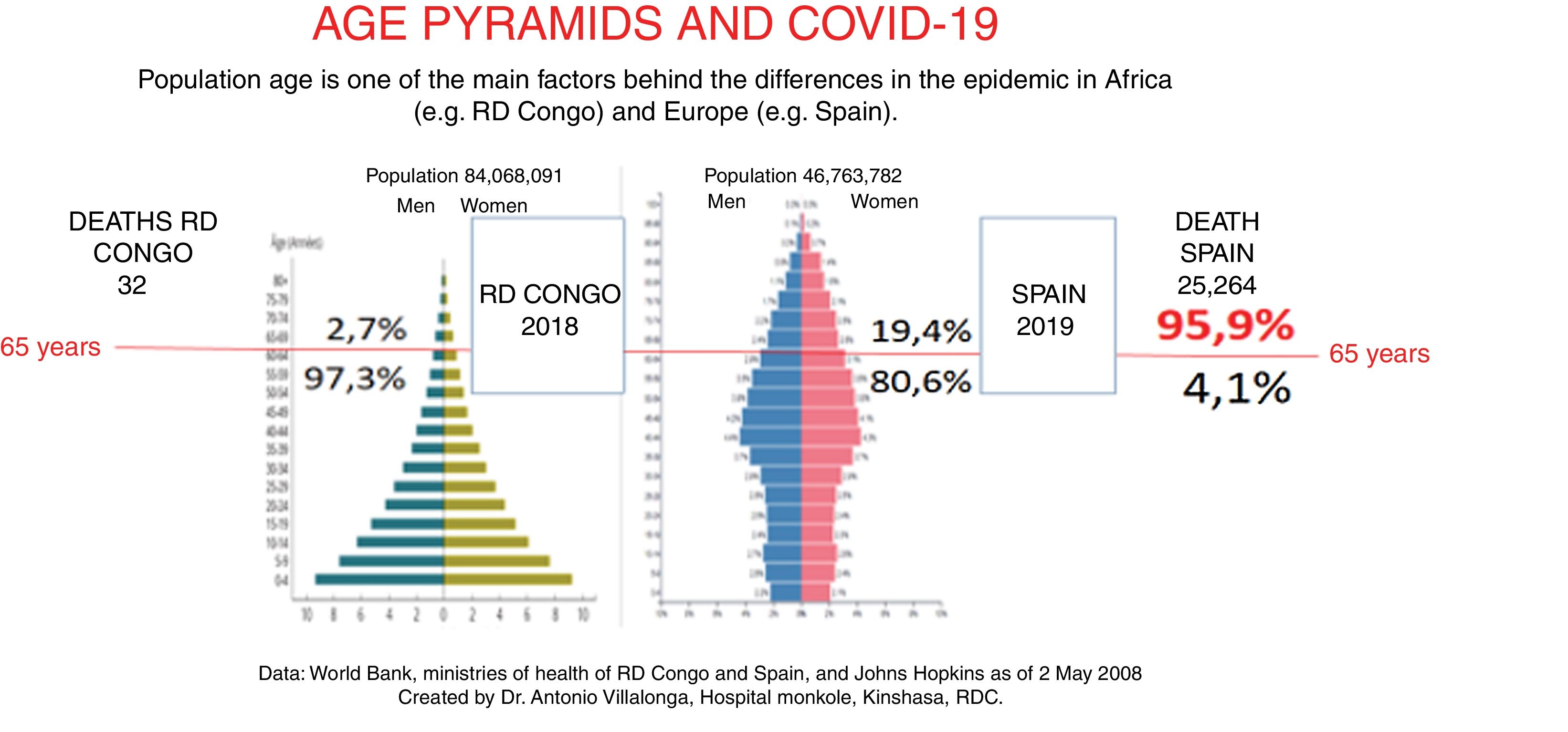

One fundamental factor is the notable differences in the age pyramid of the European and African populations. This can be seen in the example of Spain compared with DR Congo. Fig. 1 shows that in Spain, only 4.1% of Covid-19 fatalities are under 65 years of age, in other words, the virus has little effect on the young population. In DR Congo, 97.3% of the population falls within that age group. Population age is a very important factor in epidemic dynamics1,2, but it is not known with certainty why the virus affects children and young people less aggressively than the elderly. In Spain, 95.9% of fatalities were over 70 years of age, an age group that accounts for almost a fifth of the population (19.4%) - in DR Congo, it accounts for only 2.7%. However, population differences do not fully explain the relative mildness of the coronavirus in Africa, because according to calculations based on extrapolating European data, there should be many more symptomatic patients and deaths in Africa than there are.

Another factor that may be important is the ambient temperature. In Europe, temperatures in the months of February to April are cold, in Madrid they range from −3 to 19 °C, while in Kinshasa they range from 23 to 34 °C. Although there are no conclusive data, evidence suggests that the virus is not as virulent and does not spread as easily in hot climates3.

I believe there must be other factors in African populations that make them less vulnerable to the virus than people in Europe or North American, and given the fact that the African American population of the US is particularly vulnerable to Covid-194, these factors must be environmental rather than genetic. One such factor involves the immune system, specifically malaria, which affects practically all the countries and inhabitants of tropical Africa (in the hospital where I work, for example, hardly a day goes by without a health worker needing treatment for malaria). Malaria, and perhaps its treatment, could modulate the immune system in such a way that the inflammatory phase of Covid-19 is not accompanied by the cytokine storm that is the main cause of death from this infection. This is still no more than a hypothesis that needs to be investigated.

Social and political factors are also very important. Political decisions to introduce preventive measures against Covid-19 have had an obvious impact on the evolution of the epidemic, with good results in Portugal, Germany and Korea, for example. However, I believe they are not so effective here in Africa. Most Covid-19 cases and fatalities in DR Congo are concentrated in the wealthy neighbourhoods of Kinshasa, mainly among Congolese returning from Europe. Closing the borders, and isolating La Gombe, the worst affected neighbourhood in Kinshasa, from the rest of the city, has succeeded in slowing down the epidemic. The government imposed lockdown on the capital city, but the order had to be revoked the next day given the impossibility of compliance (most inhabitants live from hand to mouth – they need to work every day to eat, and houses are of very poor quality without water or electricity). Compliance with basic prevention measures, such as 1 m social distancing, avoiding crowds, washing hands or wearing a mask, is extremely poor. Last week I walked for several kilometres along the main highway going out of Kinshasa towards the Lower Congo, passing through the markets in Matadi-Kibala located on both sides of the road, where sellers, buyers, and distributors of goods accumulate on the pavements above the waste-filled gutters. Traffic is heavy along that stretch of road, and pedestrians have to make their way through thousands of people coming and going, while others are seated with their wares spread out in front of them, waiting for a buyer. Scarcely half of this jostling crowd are wearing masks, and of those that do, less than half are wearing them correctly (Fig. 2). These conditions would be expected to favour the spread of the epidemic; however, this is not the case, leading me to believe that the first 3 factors described above must be important enough to compensate for the lack of compliance with containment measures.

We can only hope that in Africa the epidemic will continue to be limited to few cases and deaths - a repeat of the European scenario in the African continent would be horrific. In Europe, health systems have responded to the demands of the epidemic, and whenever existing resources have been insufficient, additional measures have been taken, such as tripling or quadrupling the number of critical care beds in some countries. In the vast majority of African countries, health systems are unable to cover even basic health needs5. The general rule is "no money, no medicine", and in Africa poverty predominates. In DR Congo (more than 5 million inhabitants) there are less than 100 ventilators, almost all of them in the capital, so there is an obvious need not only for such equipment, but also for specialized personnel, doctors and nurses who know how to use it correctly. In short, a major international effort would have to be made to tackle an epidemic of the magnitude of the coronavirus in Europe and the US.

Conflict of interestsThe author declares no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Villalonga-Morales A. ¿Por qué es menos «intensa» la epidemia de Covid-19 en África? Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2020;67:556–558.