Implementation of Patient Blood Management programmes remain variable in Europe, and even in centres with well-established PBM programmes variability exists in transfusion practices.

Objectives and methodsWe conducted a survey in order to assess current practice in perioperative Patient Blood Management in patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement among researchers involved in POWER.2 Study in Spain (an observational prospective study evaluating enhanced recovery pathways in orthopaedic surgery).

ResultsA total of 322 responses were obtained (37.8%). Half of responders check Haemoglobin levels in patients at least 4 weeks before surgery; 35% treat all anaemic patients, although 99.7% consider detection and treatment of preoperative anaemia could influence the postoperative outcomes. Lack of infrastructure (76%) and lack of time (51%) are the main stated reasons not to treat anaemic patients. Iron status is routinely checked by 19% before surgery, and 36% evaluate it solely in the anaemic patient. Hb <9.9g/dl is the threshold to delay surgery for 61% of clinicians, and 22% would consider transfusing preoperatively clinically stable patients without active bleeding. The threshold to transfuse patients without cardiovascular disease is 8g/dl for 43%, and 7g/dl for 34% of the responders; 75% of clinicians consider they use “restrictive thresholds”, and 90% follow the single unit transfusion policy.

ConclusionsThe results of our survey show variability in clinical practice in Patient Blood Management in major orthopaedic surgery, despite being the surgery with the greatest tradition in these programmes.

La implementación de los programas Patient Blood Management (PBM) es variable en Europa, incluso en centros en los que estos programas están bien establecidos, donde existe variabilidad en cuanto a prácticas transfusionales.

Objetivos y métodosRealizamos una encuesta para valorar la práctica actual sobre PBM perioperatoria en pacientes programados para artroplastia total de cadera y rodilla, entre los investigadores involucrados en el Estudio POWER.2 en España (estudio observacional prospectivo que evaluaba las vías de recuperación intensificada en cirugía ortopédica).

ResultadosSe obtuvo un total de 322 respuestas (37,8%). El 50% de los respondedores revisaban los niveles de hemoglobina, al menos 4 semanas antes de la cirugía; el 35% trataba a todos los pacientes anémicos, aunque el 99,7% consideraba que la detección y tratamiento de la anemia preoperatoria podrían influir en los resultados postoperatorios. La falta de infraestructuras (76%) y la falta de tiempo (51%) fueron los principales motivos para no tratar a los pacientes anémicos. El estatus del hierro es revisado antes de la cirugía por el 19% de manera rutinaria, y el 36% lo evalúa únicamente en pacientes anémicos. Hb<9,9g/dl es el valor umbral para demorar la cirugía para el 61% de los clínicos, y el 22% consideraría transfundir preoperatoriamente a los pacientes clínicamente estables sin sangrado activo. El valor umbral para transfundir a los pacientes sin enfermedad cardiovascular es 8g/dl para el 43% y 7g/dl para el 34% de los respondedores; el 75% de los facultativos considera que utiliza «umbrales restrictivos», y el 90% sigue la política transfusional uno a uno (single unit).

ConclusionesLos resultados de nuestra encuesta muestran la variabilidad en la práctica clínica en PBM en cirugía ortopédica mayor, a pesar de ser el tipo de cirugía con más tradición en estos programas.

Preoperative anaemia is associated with increased morbidity1,2 and mortality3 after orthopaedic surgery and exposure to allogeneic blood transfusion4 (ABT). Patient Blood Management (PBM) uses evidence-based medical and surgical approaches to improve patient outcomes by managing anaemia, optimising haemostasis, and minimising bleeding and blood transfusion.5 Implementation of a multidisciplinary and multimodal PBM protocol reduces the need for ABT,6,7 and has been associated with a decrease in acute kidney injury, infection, hospital length of stay (LOS), mortality7 and costs.8

Although PBM protocols have been adopted by institutions worldwide, and in 2010 the World Health Organisation (WHO) urged countries worldwide to establish these programmes,9 their implementation remains variable in Europe,10 and knowledge of PBM principles11 and transfusion practices12 among European practitioners and institutions, even in hospitals with well-established PBM programmes, varies greatly.13 Unnecessary blood transfusion is a common practice worldwide,14,15 and has been described as one of the most excessively used procedures in the USA.16 There are certain barriers to the implementation of a PBM. Hospital managers must invest in resources and training and create multidisciplinary teams,17 and different hospital departments must commit to implementing PBM protocols.

We conducted a survey among investigators involved in the POWER.2 Study in Spain to evaluate current perioperative PBM practice in patients scheduled for total hip and knee replacement.18

Materials and methodsThe Perioperative Audit and Research Network Spain (REDGERM) and Anaemia Working Group Spain (AWGE) endorsed the survey after securing approval from their respective scientific and research committees.

The target population of this study were physicians participating in the POWER.2 Study, a 60-day prospective, multicentre, observational cohort study in patients scheduled for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in Spain in 2018.18 The estimated size of the target population for our survey was about 850 investigators. A study sample size calculator (total population 850, 95% confidence interval) showed that that total sample size required was 265.

We emailed POWER.2 investigators in 130 participating centres inviting them to voluntarily complete an open internet questionnaire. The email contained a link to the online questionnaire. The study was not publicised, but there was little likelihood of anyone outside the group of invitees accessing the questionnaire. Respondents’ answers were collected in each participating centre at the end of the study using survio.com, and their informed consent was implicit in completion and return of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire used was a structured, web-based form containing single and multiple answer questions. All questions were mandatory. We also recorded the time spent completing the questionnaire. Each investigator was asked to supply their name and email in order to avoid receiving several questionnaires from a single respondent. Before analysing the answers, duplicated entries in the database from the same user were deleted.

The questionnaire contained 50 questions concerning routine clinical practice in perioperative PBM. Respondents were asked to answer the questions based on their current personal clinical practice. The questions were based on the guidelines, recommendations and suggestions published by the ESA19 and NATA,20 and were categorised into: characteristics of respondents, preoperative evaluation and treatment of anaemia, measures to minimise bleeding, optimisation of anaemia tolerance, and transfusion risks. The face and content validity of the questionnaire were established and tested during the development phase by a panel of experts from AWGE (JAGE and EB) and REDGERM (JRM and AAM). The data were expressed as frequency (proportion) and analysed according to the number of responses obtained for each question. The results were reported in accordance with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES).21

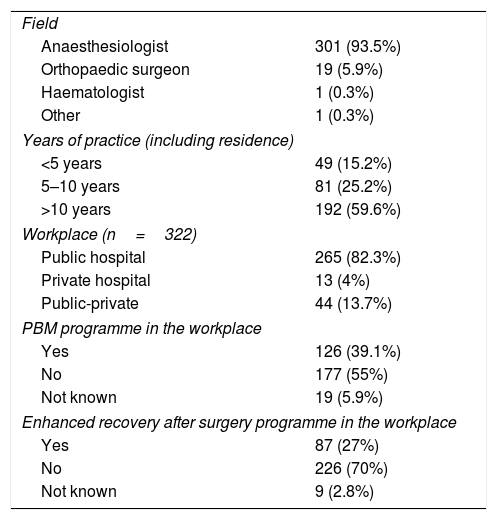

ResultsThe questionnaire was sent to 850 investigators. It was opened by 599 (70.5%) and completed by 322, giving a completion rate of 53.8%, and a response rate of 37.8%. As shown in Table 1, the majority of respondents were anaesthesiologists (93.5%) with more than 10 years of experience (59.6%), who worked in public hospitals (82.3%). More than half of the respondents (55%) stated that their hospital did not have an established PBM protocol.

Respondent demographics (n=322).

| Field | |

| Anaesthesiologist | 301 (93.5%) |

| Orthopaedic surgeon | 19 (5.9%) |

| Haematologist | 1 (0.3%) |

| Other | 1 (0.3%) |

| Years of practice (including residence) | |

| <5 years | 49 (15.2%) |

| 5–10 years | 81 (25.2%) |

| >10 years | 192 (59.6%) |

| Workplace (n=322) | |

| Public hospital | 265 (82.3%) |

| Private hospital | 13 (4%) |

| Public-private | 44 (13.7%) |

| PBM programme in the workplace | |

| Yes | 126 (39.1%) |

| No | 177 (55%) |

| Not known | 19 (5.9%) |

| Enhanced recovery after surgery programme in the workplace | |

| Yes | 87 (27%) |

| No | 226 (70%) |

| Not known | 9 (2.8%) |

Hb: haemoglobin; PBM: Patient Blood Management.

Values shown as numbers (percentage).

Regarding the detection of preoperative anaemia, 90% of responders routinely assess haemoglobin (Hb) preoperatively: 51% at least 4 weeks and 39% less than 4 weeks before scheduled surgery. Up to 10% do not routinely measure Hb, although 99.7% of respondents consider that the detection and treatment of preoperative anaemia could influence postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing THA and/or TKA.

The most likely cause of anaemia was iron deficiency (ID) in 50% of the responders and anaemia of chronic disease in 36%. Iron status is routinely reviewed by 19% prior to surgery, while 36% only measure it only in anaemic patients. However, 90.1% consider that detection and treatment of non-anaemic ID could influence outcomes in patients undergoing THA and/or TKA.

Preoperative treatment of anaemia and/or iron deficiencyRegarding treatment of preoperative anaemia, 35% of respondents treat all anaemic patients before surgery, 26% only treat anaemic or ID patients and those undergoing surgery with an estimated blood loss of over 500ml; 22% treat patients with ID, with or without anaemia, and 7% would not treat any of these patients.

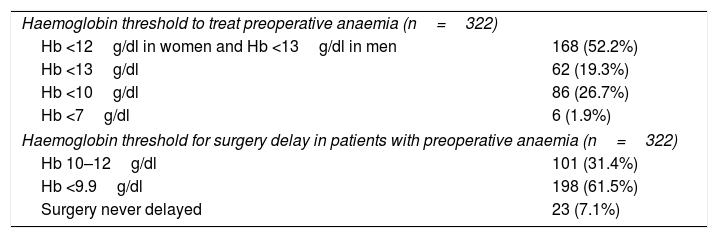

The reasons for not treating anaemic patients pre-operatively are: “lack of infrastructure” (76%), “lack of time” (51%), “costs” (15%) and “no knowledge of the benefit” (2%). Table 2 shows the Hb thresholds for treating preoperative anaemia, and the Hb threshold that would cause clinicians to delay surgery to treat patients with preoperative anaemia.

Threshold for treatment of preoperative anaemia and delay of surgery.

| Haemoglobin threshold to treat preoperative anaemia (n=322) | |

| Hb <12g/dl in women and Hb <13g/dl in men | 168 (52.2%) |

| Hb <13g/dl | 62 (19.3%) |

| Hb <10g/dl | 86 (26.7%) |

| Hb <7g/dl | 6 (1.9%) |

| Haemoglobin threshold for surgery delay in patients with preoperative anaemia (n=322) | |

| Hb 10–12g/dl | 101 (31.4%) |

| Hb <9.9g/dl | 198 (61.5%) |

| Surgery never delayed | 23 (7.1%) |

Hb: haemoglobin.

Values shown as numbers (percentage).

Asked about the threshold for treating ID, 20% of respondents routinely measure ferritin levels, and most (79%) treat patients with ferritin <50ng/ml. Regarding the Hb values that would cause responders to treat ID, 35% use WHO anaemia criteria (women with Hb <12g/d and men with Hb <13g/dl), 23% would treat women and men with Hb <13g/dl, 25% would treat patients with Hb <10g/dl, and 15% would never treat ID. The most common reasons for not treating patients with ID preoperatively are: “lack of infrastructure” (74%), followed by “lack of time” (49%), “cost” (15%) and “no of knowledge of the benefit” (6.6%).

Regarding the iron formulation chosen to treat patients with ID: 37% would choose intravenous iron, 33% oral iron, and 30% would choose both forms. For intravenous iron, 56% choose carboxymaltose iron, and 36% iron sucrose. Slightly less than half (43%) had access to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for preoperative treatment of anaemia.

When asked about the assessment of iron treatment, 83% of respondents measured post-iron therapy Hb before surgery, and 45% would not delay surgery if the patient's anaemia persisted. Up to 22% of respondents consider preoperative transfusion in clinically stable patients with no active bleeding.

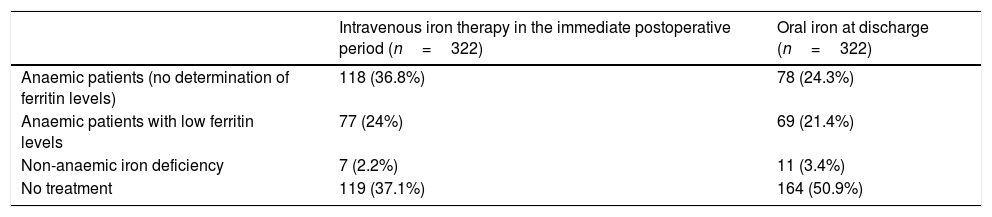

Postoperative treatment of anaemiaTable 3 shows the responses on intravenous iron therapy in the immediate postoperative period, and oral iron therapy at discharge. When asked about the chosen iron formulation, 44% of respondents used carboxymaltose iron, 40% iron sucrose, and 16% another type of formulation.

Postoperative iron therapy.

| Intravenous iron therapy in the immediate postoperative period (n=322) | Oral iron at discharge (n=322) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anaemic patients (no determination of ferritin levels) | 118 (36.8%) | 78 (24.3%) |

| Anaemic patients with low ferritin levels | 77 (24%) | 69 (21.4%) |

| Non-anaemic iron deficiency | 7 (2.2%) | 11 (3.4%) |

| No treatment | 119 (37.1%) | 164 (50.9%) |

Values shown as numbers (percentage).

Antifibrinolytic agents such as tranexamic acid are routinely administered to minimise bleeding by 97.8% of respondents. Regarding autologous blood, 27% of respondents confirmed that preoperative blood donation was performed in their centres in some cases, while 16% of responders performed normovolaemic haemodilution. Less than half (31%) of respondents use intraoperative cell savers in patients contraindicated for tranexamic acid, while 8% always use cell savers. Most (54%) respondents never use cell savers postoperatively; 32% only use them in patients contraindicated for tranexamic acid, and 11% always use these devices. Most respondents use measures to maintain normothermia: 33% use thermal blankets, 8% use fluid heaters and 57% use both.

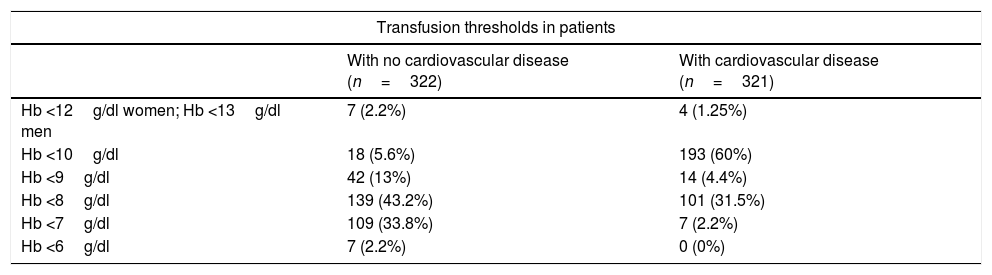

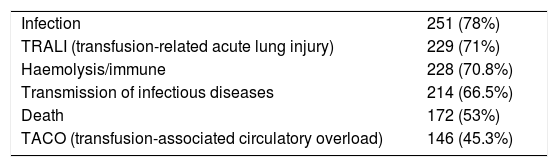

Pillar 3: Optimisation of anaemia tolerance and transfusion criteriaRespondents were asked about the transfusion threshold for patients with and without cardiovascular disease (shown in Table 4); 75% consider that they use “restrictive thresholds“; 59% confirmed that their centre has an institutional transfusion policy, and up to 10% did not know whether such a policy existed. Most respondents (90%) transfuse RBC concentrates one at a time, while 10% transfuse 2 units. In addition to Hb levels, in a question with multiple answers, 87% of respondents take hypotension into consideration, 81% tachycardia, 53% electrocardiographic changes, 47% oliguria, and 46% elevated lactate levels. Respondents were also asked about transfusion risks related to allogeneic blood transfusion in a multiple answer question (Table 5).

Pillar 3 Transfusion thresholds.

| Transfusion thresholds in patients | ||

|---|---|---|

| With no cardiovascular disease (n=322) | With cardiovascular disease (n=321) | |

| Hb <12g/dl women; Hb <13g/dl men | 7 (2.2%) | 4 (1.25%) |

| Hb <10g/dl | 18 (5.6%) | 193 (60%) |

| Hb <9g/dl | 42 (13%) | 14 (4.4%) |

| Hb <8g/dl | 139 (43.2%) | 101 (31.5%) |

| Hb <7g/dl | 109 (33.8%) | 7 (2.2%) |

| Hb <6g/dl | 7 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) |

Hb: haemoglobin.

Values shown as numbers (percentage).

Risks related to allogeneic blood transfusion (multiple answers).

| Infection | 251 (78%) |

| TRALI (transfusion-related acute lung injury) | 229 (71%) |

| Haemolysis/immune | 228 (70.8%) |

| Transmission of infectious diseases | 214 (66.5%) |

| Death | 172 (53%) |

| TACO (transfusion-associated circulatory overload) | 146 (45.3%) |

Functional reserve is routinely assessed by 56% of respondents using METS or other methods, while 44% never do so. Most respondents (54%) only use cardiac output monitoring to optimise tolerance to anaemia in very high risk patients, 23% sometimes do so, and 21% never use this technique. Similarly, 53% of respondents use goal-directed therapy based on monitoring cardiac output only in very high-risk patients.

DiscussionIn this survey we evaluated current PBM practice among researchers, mostly anaesthesiologists, from 130 Spanish hospitals who participated in the POWER.2 Study, regardless of whether or not they worked in a centre with an established PBM programme. The results of the survey shows that transfusion management in patients undergoing THA and TKA varies among respondents.

Despite sufficient evidence that preoperative anaemia is associated with a higher transfusion rate4,22,23 and worse outcomes in major orthopaedic surgery,24,25 only 35% of respondents treat all patients with preoperative anaemia. Up to 26% of patients scheduled for major orthopaedic surgery will present preoperative anaemia,26 and most scientific societies recommend preoperative determination of Hb at least 4 weeks before scheduled orthopaedic surgery to allow more time to administer corrective measures.19 In our survey, only half of the respondents have access to Hb levels 1 month in advance. Paradoxically, almost all (100%) believe that the detection and treatment of preoperative anaemia could influence postoperative outcomes, and 90% believe the same applies to treatment of ID in non-anaemic patients. In order to accelerate the recovery of Hb after surgical bleeding, international consensus guidelines recommend preoperative iron supplementation for non-anaemic patients with low iron stores scheduled for major surgery if blood loss >500ml is estimated and/or if there is a ≥10% risk of transfusion.27,28 However, the recommendation is based on a limited number of studies, and there is only weak evidence for better outcomes in non-cardiac surgery. Non-anaemic ID has been associated with increased ABT in cardiac surgery,29 with no difference in terms of morbidity and mortality. Other studies, however, have found no difference in terms of ABT requirement, although there is a tendency towards longer LOS among patients with iron deficiency.30 Waters et al. found no association between ID and postoperative complications in a cohort of 100 patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery.31 Miles et al. recently published a retrospective exploratory study in a cohort of 141 patients scheduled for colorectal surgery that suggests that patients with ID are more likely to require re-admission at 90 days of follow-up compared to patients with no ID. More studies with adequate statistical power are needed to confirm this association.32

The main reasons given by respondents for not treating preoperative anaemia are lack of infrastructure and lack of time – findings consistent with those reported by Manzini et al.11 Despite mounting evidence in favour of PBM protocols,7,33,34 and recommendations for developing national PBM programmes in Europe,35 variability persists regarding transfusion practices36 and the implementation of PBM.10 One of the main obstacles to establishing a PBM programme lies in preoperative anaemia management strategies. Establishing a protocol that would give sufficient time to evaluate these patients, which would involve postponing surgery to treat anaemia, requires the support of all departments, hospital authorities and the health services involved.

Adopting lower transfusion thresholds means that patients can be discharged with lower Hb levels than previously accepted.37 In addition, large studies have shown that the implementation of enhanced recovery pathways has decreased LOS by 3 days in THA and TKA patients,38,39 coinciding with nadir Hb levels.37 These procedures are even performed in outpatient surgeries on selected patients.40 There is scant evidence to support the association between postoperative anaemia and deficient functional recovery, and the few studies addressing this topic have published conflicting results. Postoperative anaemia has been associated with lower quadriceps strength in patients undergoing THA,41 while Jans et al. found that moderate anaemia had little clinical impact on early functional recovery in a prospective study of patients undergoing THA with a fast-track recovery programme.42 In this study, however, all patients were otherwise healthy, so this result may not be applicable to patients with comorbidities who may be less tolerant of anaemia. Consensus guidelines recommend early intravenous iron therapy over oral therapy to correct anaemia and moderate to severe postoperative ID, due to the limited effect of oral therapy in patients with chronic inflammation and low adherence to treatment because of secondary effects.19,37 Nevertheless, up to 37% of our respondents never administer intravenous iron in patients with postoperative anaemia, and almost half treat anaemic patients with oral iron on discharge.

Despite the recommendation against preoperative donation of autologous blood and normovolaemic haemodilution contained in the Seville Document on alternatives to allogeneic blood transfusion,43 27% and 16% of responders, respectively, still use this strategy in certain types of patients undergoing THA and TKA. On the other hand, the use of tranexamic acid seems to be the norm in our sample. Despite its contraindications, a European observational study published in 2016 showed that tranexamic acid was used in 39% and 43% of patients undergoing THA and TKA.10

Most of our respondents considered that they used “restrictive” transfusion thresholds. However, up to 22% would consider transfusing blood preoperatively to clinically stable patients without active bleeding, even though the Spanish Societies of Anaesthesiology and Haematology advises against this practice.43–45 Furthermore, high transfusion thresholds and/or inadequate anaemia management prior to surgery could lead to more intra- and postoperative ABT. In our survey, 61% of respondents would delay surgery to treat patients with Hb <10g/dl, and 7% would never postpone surgery. Considering that 43% would transfuse patients with Hb <8g/dl and no cardiovascular disease, and that 20% use even higher thresholds, the lack of optimisation in anaemic patients could result in avoidable ABT rates. Current recommendations suggest using a restrictive Hb threshold of 7–8g/dl, depending on the patient's comorbidities,27,31,32 and women are at higher risk of receiving ABT than men. The WHO defines anaemia as an Hb concentration of <13g/dl in men and <12g/dl in non-pregnant women.44 However, women have less body surface area and circulatory volume than men, although they will experience similar bleeding to men when undergoing the same procedures; this means that blood loss and transfusion rates are proportionally higher in women.26 Therefore, a new term has been introduced in the surgical population, pre-operative suboptimal Hb concentration, in which patients with Hb <13g/dl are considered anaemic, regardless of gender,4,5 and the same preoperative optimisation targets should be applied in both sexes.

Our survey results suggest that the PBM principles that are relevant to clinical practice are not widely implemented, and that there are certain important deficiencies that must be corrected through educational programmes that require the involvement of health services, hospital authorities, scientific societies and transfusion centres: more than half of our respondents work in hospital that have no established PBM programme; 39% do not measure Hb levels at least 4 weeks before surgery and 10% do not routinely measure Hb at all; 65% do not treat all anaemic patients; 22% would consider transfusing an anaemic patient without active bleeding preoperatively; 55% are unfamiliar with transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), despite this now being recognised as one of the most common adverse effects associated with ABT46; 49% treat postoperative anaemia with oral iron; and 41% state that their centre has no transfusion policy, or are not aware of the existence of such a policy.

One of the strengths of our survey is the high response rate (37.8%) compared to the recently published surveys by Baron et al. (7.6%)47 and Manzini et al. (15.9%)11 that evaluate PBM among European specialists. One reason for this could be that the physicians invited to participate in the survey were investigators involved in the POWER.2 Study, and therefore more likely to be willing to participate in this research. In a recent survey of Spanish doctors from centres involved in the Maturity Assessment Model in Patient Blood Management (MAPBM) project, anaesthesiologists were more aware of local PBM protocols than surgeons and other medical specialists,13 and it is therefore essential to involve different medical specialties in the implementation of the PBM programme. The vast majority of responders in our survey were anaesthesiologists who may therefore be more aware of transfusion risks and familiar with local transfusion protocols, a factor that could have caused responder bias. Furthermore, our findings in respect of iron therapy in the postoperative period should be regarded with caution, since only 6% of responders were orthopaedic surgeons, and it is these specialists who are usually responsible for the treatment of postoperative anaemia in our setting.

ConclusionsThe results of our survey illustrate the variability of PBM in major orthopaedic surgery, even though this approach has a long history of use in this type of surgery, and the high level of concern among our responders with respect to the risks of preoperative anaemia in postoperative outcomes. Strategies are needed to improve the First Pillar of PBM, particularly the treatment of preoperative anaemia and iron deficiency. Furthermore, considering the need to disseminate issues that have a bearing on clinical practice and involve various medical and surgical specialties, health authorities and national scientific societies should take the initiative to develop educational programmes at the national level.

FundingThe authors have not received any funding for this study.

Conflicts of interestCJ has received fees for conferences/consultancies from Vifor Pharma España SL, Bial, and Zambon, but not for this study. MB has received fees for attending conferences/consultancies from Vifor Pharma España SL, but not for this study. JAGE reports personal fees from Amgen, Jansen, Sandoz, personal fees from Vifor Pharma, Zambon, and non-financial support from Vifor Pharma unrelated to this study. AAM, JRM, CA, MCO, RNP and EB have no conflict of interest.

We would like the POWER Study. 2 investigators for completing the questionnaire.

Please cite this article as: Abad-Motos A, Ripollés-Melchor J, Jericó C, Basora M, Aldecoa C, Cabellos-Olivares M, et al. Patient Blood Management en artroplastia primaria de cadera y rodilla. Encuesta entre los investigadores del estudio POWER.2. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2020;67:237–244.