Coronavirus associated severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) causes a worldwide syndrome called Covid-19 that has caused 5,940,441 infections and 362,813 deaths until May 2020. In moderate and severe stages of the infection a generalized swelling, cytokine storm and an increment of the heart damage biomarkers occur. In addition, a relation between Covid-19 and neurological symptoms have been suggested. The results of autopsies suggest thrombotic microangiopathy in multiple organs. We present 2 cases of patients infected with severe Covid-19 that were hospitalized in the Reanimation Unit that presented cerebrovascular symptoms and died afterwards. A high dose prophylaxis with antithrombotic medication is recommended in patients affected by moderate to severe Covid-19.

La infección por el coronavirus asociada al síndrome de distrés respiratorio agudo severo (SARS-CoV-2) produce un síndrome clínico denominado mundialmente covid-19 que ha generado 5.940.441 infectados y 362.813 muertes hasta mayo de 20201. En estadios moderados y severos de la infección se produce una reacción sistémica del organismo caracterizada por la hiperinflamación, tormenta de citocinas y elevación de biomarcadores de daño miocárdico. Además, se ha sugerido la relación entre covid-19 y manifestaciones neurológicas. Recientes autopsias sugieren microangiopatía trombótica en múltiples órganos. Presentamos la descripción de 2 casos de pacientes con covid-19 severo, ingresados en Reanimación, que presentaron afectación cerebrovascular y fallecieron posteriormente. Se recomienda estrictamente la aplicación de profilaxis farmacológica antitrombótica en los pacientes afectados por covid-19 ingresados en cuidados críticos y se sugiere administrar dosis profilácticas por encima de la media.

The coronavirus infection associated with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) produces a clinical syndrome known worldwide as COVID-19 that has infected 5,940,441 people worldwide, with 362,813 deaths as of May 2020.1 The most common initial symptoms of the infection are fever, cough, dyspnoea, anorexia, myalgia, and diarrhoea. A systemic reaction takes place at moderate and severe stages of infection, characterised by hyperinflammation, cytokine storm and elevated biomarkers of myocardial damage. Myocardial involvement is associated with a higher risk of morbidity and mortality in infected patients. It can occur in up to 30% of patients hospitalized for COVID-19, and contributes to up to 40% of deaths, according to Chinese sources.2

There is also a suggestion that COVID-19 can be associated with neurological manifestations. In a large study in 214 patients in Wuhan, China, 78 (36.4%) developed neurological symptoms. Six of these cases presented stroke (2.8%), 5 of which occurred in severe stages of the disease.3 Various mechanisms of infection related to stroke risk have been identified, including hypercoagulability, massive systemic inflammation or “cytokine storm”, and cardioembolism caused by virus-related myocardial damage. We describe 2 cases of patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to the Resuscitation Unit who presented cerebrovascular involvement.

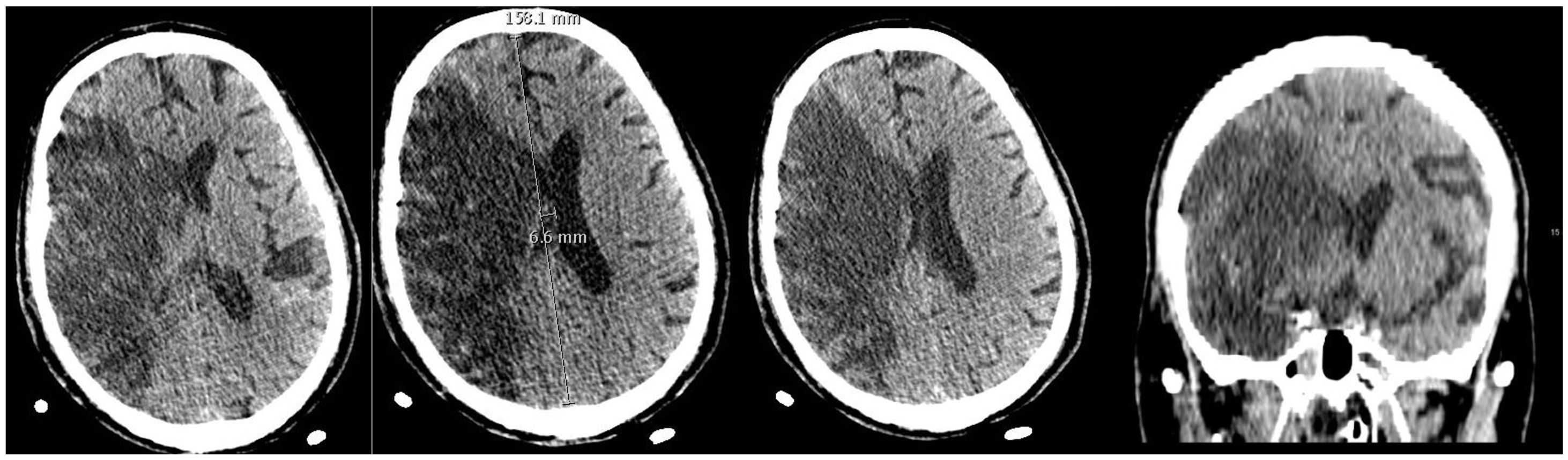

Patient 1A 71-year-old man, former smoker for 20 years, whose medical history was only significant for high blood pressure. After 15 days of respiratory disease due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, he was admitted to the Resuscitation unit due to acute respiratory failure that required orotracheal intubation and connection to mechanical ventilation and treatment with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg every 12 h for 11 days, methylprednisolone 125 mg every 24 h for 3 days, and tocilizumab 600 mg in a single dose. During his stay he presented continuous fever, acute kidney injury, arterial hypotension requiring vasopressors and several cycles of pronation, which improved respiratory function. He also presented several episodes of flutter of around 160 bpm with haemodynamic instability that required electrical cardioversion at 120 J and self-limiting episodes of atrial flutter of around 150 bpm combined with sinus tachycardia. The patient was given anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) at prophylactic doses of 40 mg/24 h adjusted for renal function. After 14 days in the Resuscitation Unit, sedation and analgesia was reduced in preparation for extubation following an improvement in lung function. After observing reduced mobility on the left side of his body, a neurological examination and brain CT were requested, which returned a diagnosis of extensive subacute infarction in the territory of the right middle cerebral artery, with significant oedema and subfalcine herniation (Fig. 1). Sixteen days after admission, the weaning protocol was initiated and the patient was extubated. On neurological examination, he presented stupor, non-reactive isochoric pupils, mutism, inability to follow instructions, and no reaction to painful stimulus. We observed left facial paresis and left hemiplegia. Anti-aggregation was started with inyesprin 450 mg. Despite treatment, the patient deteriorated and ultimately died.

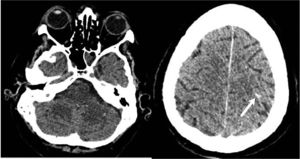

Contrast-enhanced brain CT scan of patient 1. Extensive area of right fronto-temporoparietal corticosubcortical hypodensity extending to the ipsilateral basal ganglia associated with subacute infarction in the territory of the right middle cerebral artery that causes a mass effect with obliteration of cortical sulci in right convexity, narrowing of the ipsilateral lateral ventricle and midline shift 6.6 mm to the left. Hyperdense linear images are observed In the region of some right cortical sulci. Although these may correspond to impinging cortical areas, an associated cortical or subarachnoid microbleeding component cannot be ruled out.

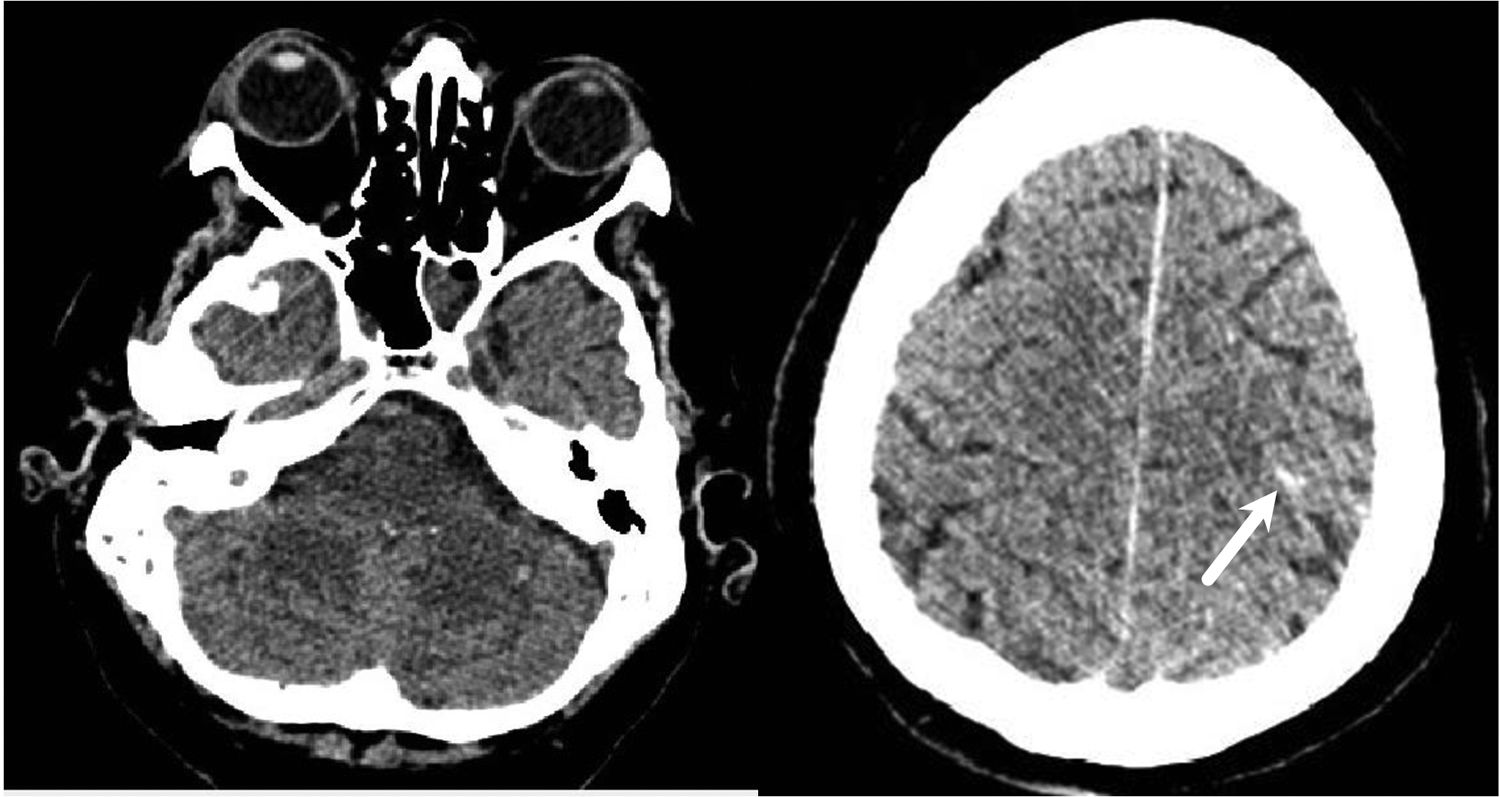

A 63-year-old man, former smoker for more than 10 years with a history of rheumatoid arthritis, extrinsic allergic alveolitis, and monoclonal IgG Kappa gammopathy. He was admitted to critical care for 19 days, requiring orotracheal intubation due to acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19, and was given the following treatment: methylprednisolone 125 mg for 2 days, prednisone 60 mg for 3 days, lopinavir/ritonavir 400 mg every 12 h for 11 days, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg every 12 h for 2 days, and interferon beta 250 µg every 48 h for 7 days. After being discharged from critical care once the lung injury had resolved, he presented fever, generalised weakness and increasingly impaired level of consciousness, and was re-intubated and returned to Resuscitation. A cranial CT scan was performed, which showed no signs of acute ischaemia, no intracranial haemorrhage or other signs of acute pathology.

On admission to Resuscitation, the patient presented haemodynamic instability, requiring vasoactive drugs, fever of up to 40 °C, septic shock with multiorgan dysfunction and acute kidney failure that required continuous veno-venous haemofiltration (CVVH). He also presented an episode of wide QRS tachycardia of up to 140 bpm that did not subside immediately after 3 attempts at electrical cardioversion, and repolarization abnormalities in the inferolateral leads, with increased troponins. An echocardiogram was performed, which revealed hypocontractility of the apical segments with preservation of other tissue, leading to a diagnosis of probable myocarditis secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. The patient was anticoagulated with low doses of LMWH at 20 mg/24 h due to episodes of melena and anaemia.

Multiorgan failure improved over the following 5 days, allowing us to withdraw sedation; however, the patient was disoriented and did not respond to stimuli. After 3 days with persistent disorientation, he was examined by a neurologist and an electroencephalogram was performed, which showed moderate disorganization and generalized background slowing. A brain CT scan was performed in which densitometry showed changes in the appearance of the cerebellar parenchyma that suggested recent hypoxic-ischaemic pathology and an image compatible with pinpoint bleeding in the sulcus of the left frontal lobe, with a poor prognosis (Fig. 2). The patient eventually died.

DiscussionAlthough many aspects of the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection are still unknown, there is evidence of a significant increase in cardiovascular events. This leads to greater morbidity and mortality in patients, especially those admitted to critical care (44.4% versus 6.9% in non-critical patients4). Cases of myocardial ischaemia, heart failure, arrhythmia and arterial and venous thromboembolism have been observed in these patients, as well as elevations of cardiac injury biomarkers (cardiac troponin, Nt-proBNP).2 These complications frequently occur 15 days after the onset of fever. In addition, patients with cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, etc.) have a higher risk of severe COVID-19 disease and COVID-related complications, and therefore the strict preventive measures recommended by the WHO and CDC should be applied.

Likewise, various studies have shown that COVID-19 can cause neurological damage. According to Mao et al., 5.7% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection developed cerebrovascular disease over the course of their illness.3 According to Klok et al., the incidence of thrombotic complications in patients infected with COVID-19 is 31%.4 Furthermore, an increased risk of cerebrovascular events has been identified in patients with prothrombotic risk factors.

Recent studies, such as that of Ferrando et al., have described the marked changes in haemostasis that occur with this syndrome, such as over-production of fibrinogen, ferritin or D-dimer, which has been suggested as a prognostic marker of the disease.5 They insist on the importance of anticoagulant treatment, titrating the dose according to the risk factors or thrombotic findings.

Few data are available from autopsies and pathophysiological studies, but recent autopsies suggest thrombotic microangiopathy in multiple organs. In a recent study in the pulmonary vascular alterations of 7 patients who died from Covid-19, Ackermann et al. observed 3 distinctive angiocentric features of Covid-19.6 The first was severe endothelial injury associated with intracellular SARS-CoV-2 virus that appears to damage the endothelial cell membrane. Second, the lungs from patients with Covid-19 had widespread vascular thrombosis with microangiopathy and occlusion of alveolar capillaries. Third, the lungs from patients with Covid-19 had significant new vessel growth through a mechanism of intussusceptive angiogenesis.

There are still no comprehensive reports of brain autopsy from infected patients. However, a possible mechanism of action of cerebrovascular accidents could be hypercoagulability, with the resulting formation of micro- and macro-thrombi in the vessels. Another reason could be the infection-induced hypoxia observed in these patients.

A thorough neurological examination should be performed in patients with COVID-19, including headache, altered consciousness, anosmia, paraesthesia, and other pathological neurological signs. Additionally, a recent study reported the presence of the viral genome in cerebrospinal fluid in an infected patient with neurological involvement, opening up a new approach to monitoring in parallel with symptoms.7 Elevated PCR and D-dimer levels indicate increased inflammation and abnormalities in the coagulation cascade, respectively, which play a role in the pathophysiology of cerebral ischaemia.8 Elderly patients and those with prothrombotic risk factors should be carefully monitored. During the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 infection should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with pathological involvement of the central nervous system. This will prevent both diagnosis delays or errors and limit the spread of the virus. Healthcare teams must bear in mind that cerebrovascular events can be a presenting symptom of COVID-19, and must protect themselves from infection when dealing with these patients.

More studies are needed to determine the best supportive treatment for cardiovascular involvement and the high risk of hypercoagulability caused by this disease, and it is important to bear in mind that these patients are at high risk of cardioembolism. Anticoagulant dosing used in existing hospital protocols could be insufficient. Experts recommend administering pharmacological thrombosis prophylaxis, possibly at high doses, in all COVID-19 patients admitted to critical care.4

ConclusionSARS-CoV-2 infection has a multisystem involvement. The widely differing presenting symptoms of the COVID-19 syndrome shows that it cannot be considered a disease with a single phenotype, but rather a pathology that differs in its form of presentation and course in different individuals.

More studies are needed to identify the neurological involvement in COVID-19. Future epidemiological studies and case registries should determine the real incidence of these neurological complications, their pathogenic mechanisms, and the therapeutic options available. As no effective treatment has yet been discovered, it would be interesting to perform more autopsies in SARS-CoV-2 non-survivors to gain a more detailed, comprehensive understanding of the COVID-19 syndrome.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Azpaiazu Landa N, Velasco Oficialdegui C, Intxaurraga Fernández K, Gonzalez Larrabe I, Riaño Onaindia S, Telletxea Benguria S. Afectación cerebrovascular isquémico-hemorrágica en pacientes con covid-19. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redar.2020.08.002