The cause of the COVID-19 pandemic is severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Severe forms of the disease occur predominantly in older adults or in individuals with underlying medical comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, and chronic kidney disease. The reason for the fatality of COVID-19 is viral sepsis. This host organ dysfunction is caused by a life-threatening, dysregulated inflammatory response (DIR) that initially has severe pulmonary complications.1,2 Therefore, there is generalized endothelial dysfunction leading to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

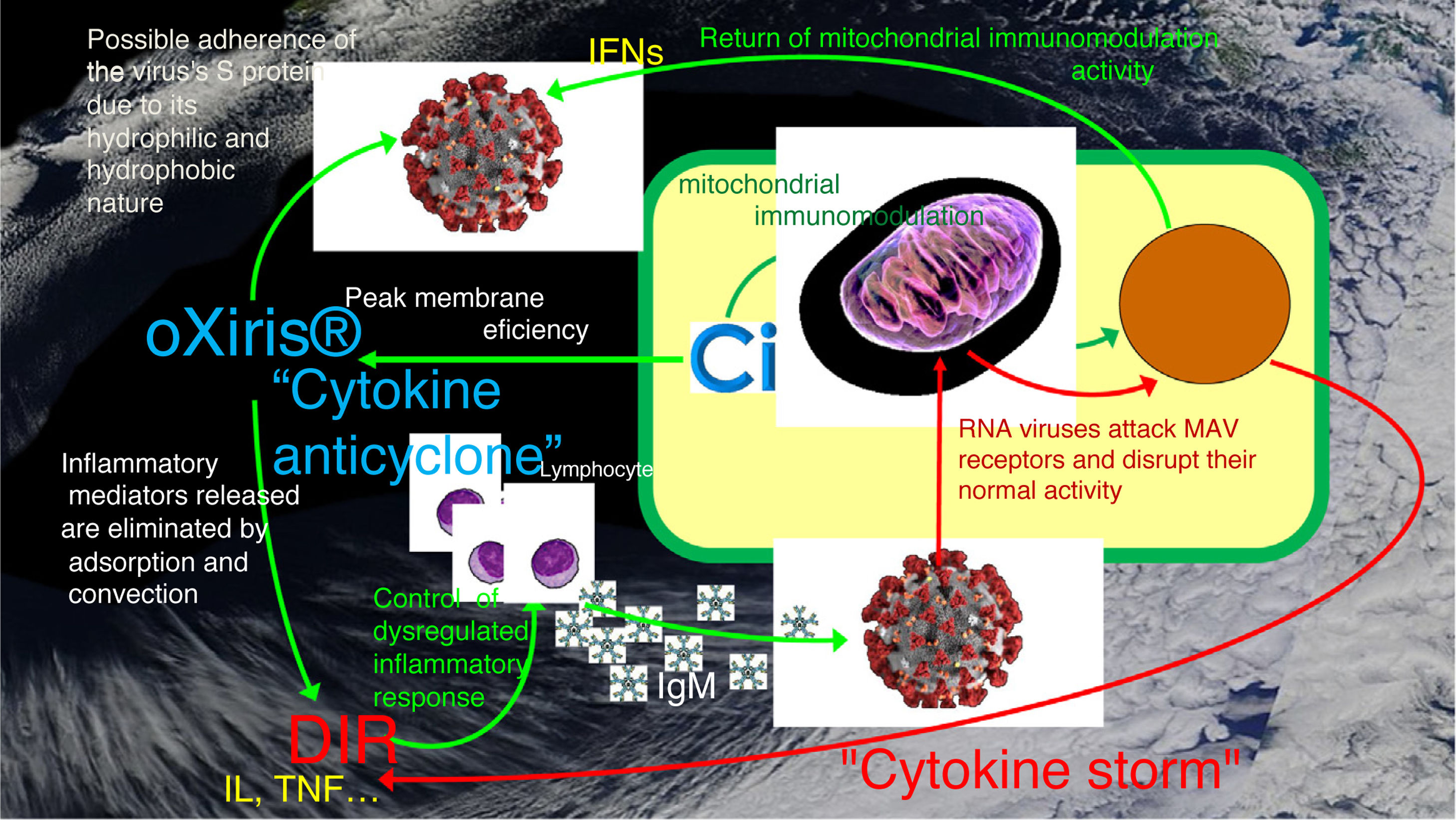

Emerging evidence suggests that some patients may respond to COVID-19 with a disproportionate “cytokine storm,” called secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).3,4 This, however, is not merely a quantitative problem, and dysregulated inflammatory response, which is a functional problem not just a particular cytokine threshold is a better term to describe this phenomenon. This response must be associated with an organ dysfunction to be considered pathological.5 Currently, although there are some promising data, there is insufficient evidence to support the recommendation for a specific, effective treatment for patients with COVID-19.6 While numerous antiviral treatments are under investigation, their exclusive use may not be sufficient to control the aforementioned dysregulated inflammatory response. Therefore, there is growing interest in identifying alternatives with immunomodulatory action that can eliminate or reduce the formation of cytokines, thereby reducing both inflammatory tissue damage, particularly lung damage,7 and mortality. An optimal blood purification technique could play a key role in this context.8

The CONVEHY® protocol (online supplements 1, 2, 3) was developed by the Hyperfiltration Research Group to control DIR and the cytokine storm through immunomodulation in patients with septic shock.9 The DIR can be triggered by various events, including viral infections such as COVID-19, and can have different systemic effects on endothelial glycocalyx, such as vasodilation, fluid extravasation, and platelet micro-aggregation, in addition to kidney injury. Immunomodulation strategies that involve the elimination of inflammatory mediators should be considered in patients with poor response to treatments.10

The oXiris® membrane5 (BaxterTM, Illinois, USA) is hollow fibre acrylonitrile and methanesulfonate (AN69ST) membrane with a surface treated with polyethyleneimine (PEI) and anchored heparin (AN69-ST-anchored heparin). It is a haemofilter that can eliminate interleukins (IL), tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), migration inhibitory factor (MIF), interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL1-ra), high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB-1), lipopolysaccharides (LPS), fibroblast growth factors (FGF21, FGF23), complement factors (C3a, C5a), and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), in addition to endotoxins. Its ability to remove molecules is related to its electrical charge, and therefore its isoelectric point. Although clinical experience in COVID-19 is limited,11–13 in a single-centre, randomized, double-blind clinical trial, oXiris® proved effective in purifying blood and reducing the need for vasoactive agents in bacterial sepsis.14 The Prismaflex system™ (BaxterTM, Illinois, USA) is used in conjunction with oXiris®. CONVEHY® uses a dose of citrate in a specific stage of the process, in this case specifically adapted to COVID-19. Adsorption capacity decreases over time due to membrane saturation, and membrane replacements are scheduled every six hours, at the discretion of the physician. The membrane can also be used solely for hemofiltration if only renal support is required at that time. The preliminary results of the use of the CONVEHY® protocol comparing outcomes before and after the inclusion of citrate have recently been published.9

The SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain spike (S) binds to the ACE2 receptor through a remarkable network of hydrophilic interactions. Multiple bonds and two salt bridges can be found at the interface of this complex, with multiple tyrosine residues forming hydrogen-bonding interactions with the polar hydroxyl group.15,16 The aforementioned hydrophilic and hydrophobic characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 virus allows it to adhere to the oXiris® membrane.17,18 Similar adsorption-based removal by lectin affinity plasmapheresis has been studied in other RNA viruses such as hepatitis C and Ebola virus.19

The oXiris® membrane was given an emergency use authorization (EUA) by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat patients with confirmed COVID-19. This technique can be used to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in adult patients presenting any of the following conditions:

- •

Early acute lung injury/early ARDS.

- •

Serious disease

- •

Life-threatening disease, defined as:

- -

Respiratory insufficiency

- -

Septic shock and/or

- -

Multiple organ dysfunction or failure.

- -

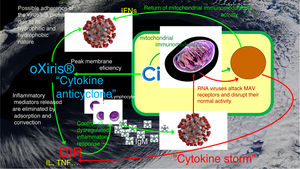

Being an RNA (ribonucleic acid) virus, SARS-CoV-2 directly affects the immunomodulatory function of the mitochondria by modifying the mitochondrial antiviral signalling (MAV) receptors, thereby preventing interferon synthesis by the innate immune response. Other interleukins can also be modulated in the same way.20

If the inflammatory response can be controlled in time, the immune system may be able to produce antibodies and overcome the infection.21 The same strategy is used by our group in bacterial shock, although in this case we facilitate and allow time for antibiotics to act, and also determine whether the root cause can be controlled or an invasive treatment is needed. The use of high doses of citrate may be more beneficial that heparin with the oXiris® membrane due to:

- 1.

Greater membrane efficiency – there is less activation of leukocytes and platelets and therefore less saturation22 and greater durability at peak performance.

- 2.

The PEI surface treatment is not completely saturated with the initial sodium heparin flushing solution – more PEI is available for adsorption;

- 3.

The unpredictable negative effect of heparin in patients with septic shock and ischaemia–reperfusion injury, which could cause inflammation and microthrombi in the microcirculation23 and have disastrous effects on COVID-19 patients. Microthrombus involvement in the microcirculation has been described in autopsies of these patients24;

- 4.

Citrate, being a substrate of the respiratory cycle, can act at the mitochondrial level to improve metabolic alterations and keep respiratory complexes active, thus avoiding apoptosis25;

- 5.

Citrate can revive mitochondria and their respiratory and immunomodulatory function.20

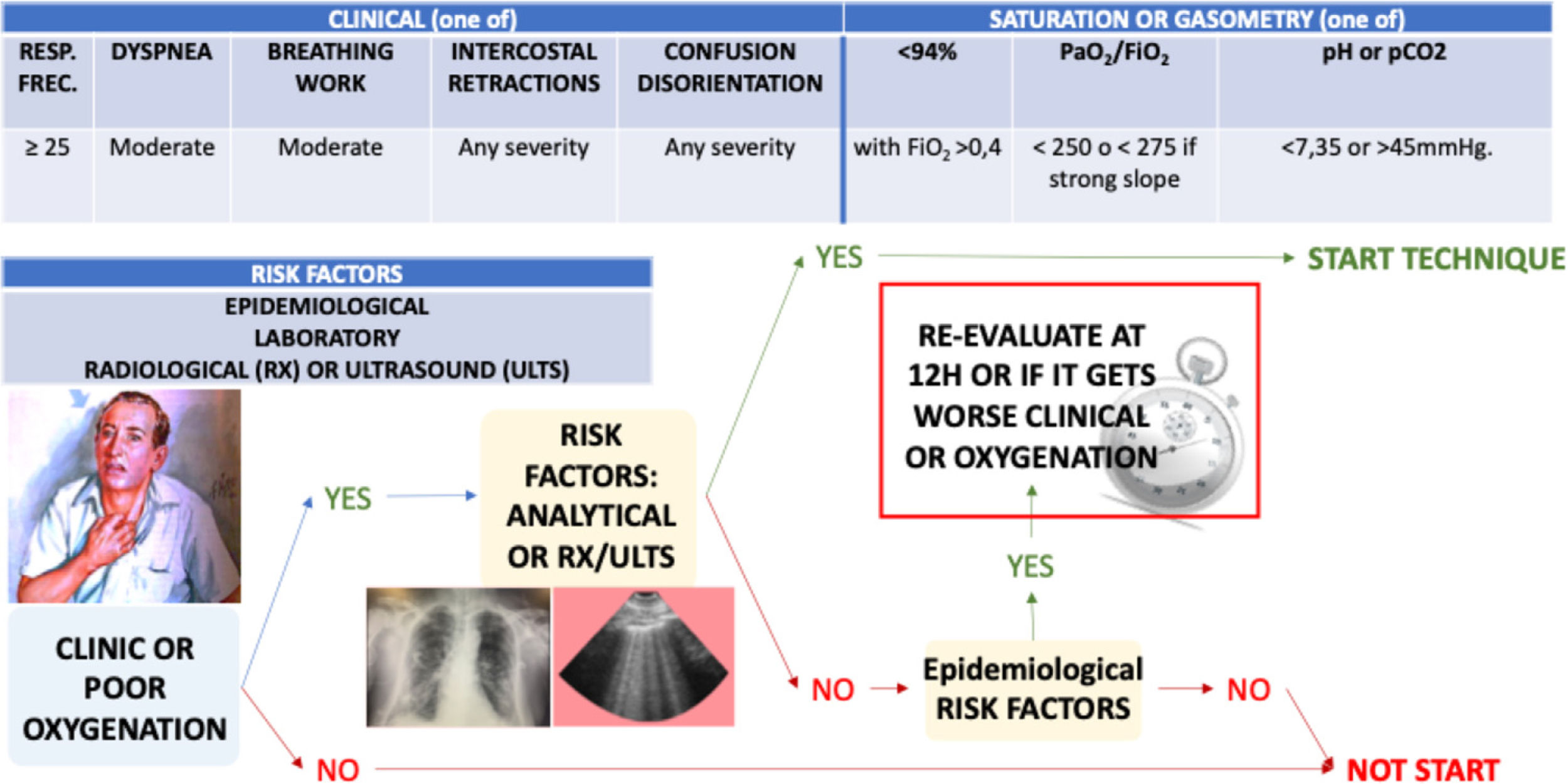

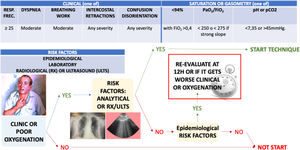

We believe that combining an effective adsorptive cleaning strategy with oXiris®, with controlled convection that helps eliminate inflammatory molecules, together with the effect of citrate on the mitochondria can result in faster and better recovery. This opinion contrasts with other solely renal support approaches (Fig. 1). In patients with COVID-19 timing the start of the technique can be decisive, and for now we have to rely on epidemiological and clinical risk factors for this purpose (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Combined immunomodulation strategy of the CONVEHY® protocol. oXiris®: trademark of the acrylonitrile 69-surface-treated heparin-anchored membrane; Ci: citrate; RNA: ribonucleic acid; DIR: dysregulated inflammatory response; IFNs: interferon; IL: interleukin; TNF: tissue necrotic factor; IgM: immunoglobulin M; curved red arrow: reduction or deterioration; curved green arrow: activation or enhancement.

Indication for the early immunomodulation technique for COVID-19 (EIT-C19): patients with manifest symptoms or poor oxygenation who have signs of COVID-19 either on X-ray, pulmonary ultrasound and/or laboratory tests. Particular focus on the subgroup with epidemiological risk factors. See decision tree.

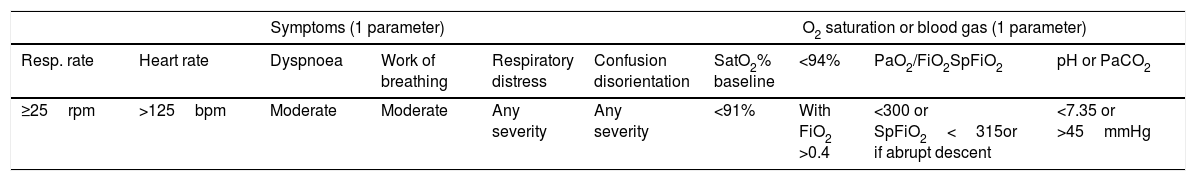

Risk factors for severe disease.

| Symptoms (1 parameter) | O2 saturation or blood gas (1 parameter) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resp. rate | Heart rate | Dyspnoea | Work of breathing | Respiratory distress | Confusion disorientation | SatO2% baseline | <94% | PaO2/FiO2SpFiO2 | pH or PaCO2 |

| ≥25rpm | >125bpm | Moderate | Moderate | Any severity | Any severity | <91% | With FiO2 >0.4 | <300 or SpFiO2<315or if abrupt descent | <7.35 or >45mmHg |

| Epidemiological | Laboratory | Radiological or ultrasound |

|---|---|---|

| >65 years | D-dimer>1000ng/mL | Multilobular infiltrates. |

| History of lung disease | CPK>twice baseline | Completely diffuses, widely spaced B lines (“Berticals”) (moving with pleura) Waterfall sign. “White” lung.Pleura thickened, irregular.Healthy and diseased lung patches.Subpleural consolidation. |

| Mod-sev CKD | CRP>100mg/L | |

| DM HbA1c>7.6% poorly controlled | LDH>500U/L | |

| Uncontrolled HT | Elevated troponin | |

| Cardiovascular disease | Ferritin>1000μg/L | |

| Transplantation or other immunosuppression | Lymphopenia<500/mm3 | |

| HIV with CD4<500/mm3 |

Resp. rate: respiratory rate; rpm: respirations per minute; Heart rate: heart rate; bpm: beats per minute; FiO2: fraction of inspired O2; PaO2/FiO2: ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen; SpO2/FiO2: ratio of peripheral oxygen saturation to percentage of inspired oxygen; PaCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood.

CPK: creatine phosphokinase; mod-sev CKD: moderate–severe chronic kidney disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; DM HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin in patients with diabetes mellitus; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; HT: arterial hypertension; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; CD4: CD4 lymphocytes or T4 lymphocytes.

CONVEHY® COVID-19 is intended as an early use protocol or rescue technique. It is designed to act as an anticyclone for the cytokine storm, thus restoring proper immune function. Its effectiveness could make it suitable for use in dialysis centres and critical care units, where it can treat as many patients as possible.

FundingThe authors have not received any funding.

Conflict of interestsRafael García-Hernández has carried out consulting and conference work in hospitals funded by Baxter SL.

Co-authors of the CONVEHY GROUP® RESEARCH:

- 1.

Rafael García-Hernández. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Head of the Post-surgical Resuscitation Unit. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 2.

María Isabel Espigares-López. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 3.

Reyes Gámiz-Sánchez. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Internal Medicine specialist. Head of the Post-surgical Resuscitation Unit. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 4.

Francisco Miralles-Aguiar. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Internal Medicine specialist. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 5.

Francisco Javier Arroyo Fernández. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 6.

Miguel Ángel Moguel-González. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz. Spain

- 7.

Gonzalo García-Benito. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Internal Medicine specialist. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario de Salamanca. Spain

- 8.

María Victoria García-Palacios. Specialist in Preventive Medicine. Preventive Medicine Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 9.

Manuel Samper. Specialist in clinical analysis. Clinical Analysis Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 10.

Beatriz Gómez Tapia. Anaesthesiology resident Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 11.

Patricia Martín Falcón. Anaesthesiology resident Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 12.

Pablo Jorge-Monjas. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid. Spain

- 13.

Carlos Márquez Rodríguez. M.D., Ph.D. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 14.

Encarnación Meléndez Leal. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 15.

Anabel Carnota Martín. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 16.

Aurora Piña Gómez. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 17.

Iván Ramírez Ogalla. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 18.

Estefanía Cabezuelo Galache. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 19.

Carmen Fernández Mangas. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 20.

Carmen Fernández Riobó. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 21.

Manuel Muñoz Alcántara. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 22.

Manuel Mato Ponce. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 23.

Francisco J Pérez Bustamante. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 24.

Antonio Pérez Pérez. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 25.

José Ramón Ferri Ferri. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 26.

Ángela Gonzálvez Galinier. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 27.

Pedro De Antonio del Barrio. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 28.

María Borrego Costillo. Anaesthesiology resident Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 29.

Elena Borreiros Rodríguez. Anaesthesiology resident Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 30.

Irene Delgado Olmos. Anaesthesiology resident Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 31.

Ana Martínez-Almendro Fernández. Anaesthesiology resident Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 32.

Paula Lozano Hierro. Anaesthesiology resident Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 33.

Isidoro Jiménez Pérez. Haemofiltration nurse. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 34.

Carlos García Camacho. Perfusionist nurse. Cardiovascular Surgery Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 35.

Antonio Pernia Romero. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 36.

María Jesús Sánchez del Pino. Department of Biomedicine, Biotechnology and Public Health. Biochemist. University of Cádiz – Spain

- 37.

Manuel Antonio Rodríguez Iglesias. Department of Biomedicine, Biotechnology and Public Health. Biochemist. University of Cádiz.

- 38.

Eduardo Tamayo Gómez. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid. Spain

- 39.

Gerardo Aguilar. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology Service. Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia. Spain

- 40.

Manuel E. Herrera Gutiérrez. Internal Medicine specialist. Intensive care unit. Hospital Regional Universitario Carlos Haya. Spain

- 41.

Luis Miguel Torres Morera. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Head of the Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

- 42.

Enrique Calderón Seoane. M.D., Ph.D. Specialist in Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation. Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz – Spain

Please cite this article as: García-Hernández R, Espigares-López MI, Miralles-Aguiar F, Gámiz-Sánchez R, Arroyo Fernández FJ, Pernia Romero A, et al. Inmunomodulación mediante CONVEHY® para COVID-19: de la tormenta al anticiclón de citoquinas. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2021;68:107–112.

All the authors have made substantial contributions in each of the following aspects: the conception and design of the study, or the acquisition of data, or the analysis and interpretation of the data, the draft of the article or the critical review of the intellectual content and the final approval of the version presented.