The European Diploma in Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care (EDAIC) has become a standard of quality among Spanish anaesthesiologists. The aim of this retrospective observational study was to assess the results of Spanish participants for the Part 1 and Part 2 exams over a recent five years period from 2012 to 2016 and 2013 to 2017, respectively.

Material and methodsAfter obtaining the authorization from the European Society of Anaesthesiology, the results of both parts of the EDAIC exams were anonymously analysed for five years. We analysed the number of registrations, the pass rates, the cause for failure and the mean scores for basic sciences (paper A of part 1 exam and the two first vivas of part 2 exam) and clinical anaesthesia and intensive care (paper B of part 1 exam and the two last vivas of part 2 exam). Quantitative variables were analysed using the one-way analysis of variance, and qualitative variables using the chi-square test for trends. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsFor the written part 1 exam, 1189 of a total of 10,954 candidates (10.85%) were registered in Spanish centres, reflecting the global growth of the exam (p=0.29). The pass rate was 62.1%, with no significant differences from other countries (p=0.38). Basic sciences were involved in 84.1% of failing candidates. Mean scores were 71.74±5.98% for basic science (paper A) and 74.48±4.29% for clinical anaesthesiology (paper B). Regarding the part 2 exam, 72.4% of the candidates who had passed the part 1 exam registered for the oral part 2, with a pass rate of 62.7% versus 62.2% in the rest of the world (p=0.91). Failing in the basic sciences sections of the part 2 resulted in 93.8% of candidates failing the part 2 exam. Bad fails were registered in 56 (31.5%) of failing candidates, of which 71.3% occurred in the basic sciences vivas. Isolated bad fails only occurred in 7 (3.9%) cases.

ConclusionsThe evolution of the EDAIC in Spain has been very similar to evolution of the EDAIC in the rest of the world. Further efforts to improve knowledge in basic sciences and better preparation in the technique of oral examination should improve the pass rate of the EDAIC examinations from an ever-increasing cohort of candidates.

El Diploma Europeo en Anestesiología y Cuidados Intensivos (EDAIC) se ha convertido en un estándar de calidad entre los anestesiólogos españoles. El objetivo de este estudio retrospectivo observacional fue valorar los resultados de los participantes españoles en los dos exámenes —parte 1 y parte 2— en un periodo reciente de 5años, entre 2012 y 2016 y entre 2013 y 2017, respectivamente.

Material y métodosDespués de obtener la autorización de la European Society of Anaesthesiology, los resultados de los dos exámenes del EDAIC fueron analizados de manera anónima en un periodo de 5 años. Analizamos el número de inscripciones, la tasa de aprobados, la causa de suspensos y la nota media en ciencias básicas (cuadernillo A de la parte 1 del examen y las dos primeras mesas de la parte 2 del examen) y en anestesiología clínica y cuidados intensivos (cuadernillo B de la parte 1 del examen y las dos últimas mesas de la parte 2 del examen). Las variables cuantitativas fueron analizadas con análisis de varianza y las variables cualitativas con test de chi-cuadrado para tendencias. El nivel de significación estadística fue establecido en p<0,05.

ResultadosPara la parte 1 del examen escrito, 1.189 de un total de 10.954 candidatos (10,85%) fueron inscritos en centros españoles, reflejando el crecimiento global del examen (p=0,29). La tasa de aprobados fue del 62,1%, sin diferencias significativas con los demás países (p=0,38). Las ciencias básicas supusieron el 84,1% de los suspensos. La nota media fue de 71,74±5,98% para las ciencias básicas (cuadernillo A) y de 74,48±4,29% para la anestesiología clínica (cuadernillo B). En relación con la parte 2 del examen, el 72,4% de los candidatos aprobados en la parte 1 del examen se inscribieron en la parte 2, con una tasa de aprobados del 62,7%, versus el 62,2% en el resto del mundo (p=0,91). Los suspensos en las mesas de ciencias básicas de la parte 2 del examen supusieron el 93,8% de los candidatos suspensos en la parte 2 del examen. Los suspensos eliminatorios en una mesa fueron registrados en 56 (31,5%) de los candidatos suspensos, de los que el 71,3% se produjeron en las mesas de ciencias básicas. Los suspensos eliminatorios aislados se produjeron solo en 7 (3,9%) de los candidatos.

ConclusionesLa evolución del EDAIC en España ha sido muy similar a la del resto del mundo. En el futuro, los esfuerzos persistentes de los anestesiólogos españoles para mejorar sus conocimientos en ciencias básicas y preparar mejor la técnica del examen oral podrían mejorar la tasa de aprobados en el EDAIC en una cohorte de candidatos en constante aumento.

In the last 20 years, the development of the European Union (EU) led to the free circulation of goods, services, capital and persons thanks to different political arrangements and EU parliament directives,1 which were progressively adapted into the national legislation of each member state. When applied to medical professionals, and more specifically to anaesthesiologists, mutual recognition of diplomas among the EU members was implemented despite a significant disparity in the length and quality of training, consequently leading to significant differences in professionals’ level of expertise depending on where they were trained.2

The European Diploma in Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care (EDAIC), which has been considered a mark of excellence in our specialty since its creation in the mid of the 1980s,3 has experienced a significant growth in terms of number of registrations and diplomates in the last decade.4 The 2 exams to obtain this diploma have been designed to assess global knowledge in all the curricular aspects of our specialty, and follow the syllabus created by the European Board of Anaesthesiologists (EBA) and the Union Européenne des Médecins Spécialistes (UEMS).5 It is endorsed by the EBA and the UEMS,6 and part or all of the exam was adopted in various European countries as a mandatory step to achieve specialist status in our specialty.4,7

In Spain, training in Anaesthesia and Critical Care is a 4-year programme. At the end of their training, residents are not required to undergo a formal evaluation that would confirm the acquisition of theoretical and practical knowledge before obtaining their specialist diploma,8 even though the EDAIC is without doubt highly regarded by many anaesthesiologists and heads of departments of anaesthesiology. Since it is not mandatory, no data is currently available concerning the number of Spanish anaesthesiologists who applied for and passed the different parts of the exam, how they performed compared with candidates from other countries, and how many Spanish anaesthesiologists have become diplomates of the ESA (DESA) in recent years.

The objective of this retrospective observational study was to assess the evolution of the results of Spanish candidates, and the number of anaesthesiologists who obtained the DESA in the past 5 years.

Material and methodsAfter obtaining authorization from the EDAIC Examinations Committee and secretariat, all the results of Part 1 (written) and Part 2 (oral) of the EDAIC exams sat by Spanish-speaking candidates were collected anonymously in Spanish centres between 2012 and 2016 for Part 1, and 2013 and 2017 for Part 2.

Data collectionWe collected the following data for each candidate sitting Part 1 of the exam: year of registration, paper A (basic sciences) and paper B (clinical anaesthesia and intensive care) results, the pass/fail mark for each paper and the overall pass/fail result (to pass the Part 1 exam, it is necessary to pass both basic sciences and clinical papers).

For Part 2 of the exam, we collected the following data for each candidate: year of presentation, and the mark of each viva, according to the marking system used at that time (1: Bad fail; 1+: narrow fail; 2: Pass; 2+: excellent pass), and their final pass/fail result (to pass the exam, it is necessary to pass at least 3 vivas, with no bad fail in any viva).

AnalysisAnalysis of part of the 1 exam: The number of candidates and the overall pass rate of the exam were measured for the whole period and compared between years. They were also compared with the overall pass rate of candidates from all other countries. We analysed the cause of failure (due to Paper A, Paper B, or both), and compared the cause of failure between years, to assess the level of preparation of candidates.

The score for each paper was also analysed, comparing results between years, and with the overall result of candidates from the other countries for each year.

Analysis of the Part 2 exam: The number of candidates and overall pass rate of Part 2 were analysed for the whole period and compared between years. They were also compared with the overall pass rate of candidates from all other countries by year. The reasons for failure were also analysed, categorizing them as basic sciences failure, clinical anaesthesiology failure or overall failure; this analysis was done for the whole period and between years. We also assessed the incidence of bad fails and compared it between years.

Data were computed in a Microsoft excel sheet and analysed separately for each exam, using SPSS v.21 (Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables were analysed using analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test or Wilcoxon test for non-parametric variables, and categorical variables were analysed using Chi-square test for trends or Fisher exact test when appropriate. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

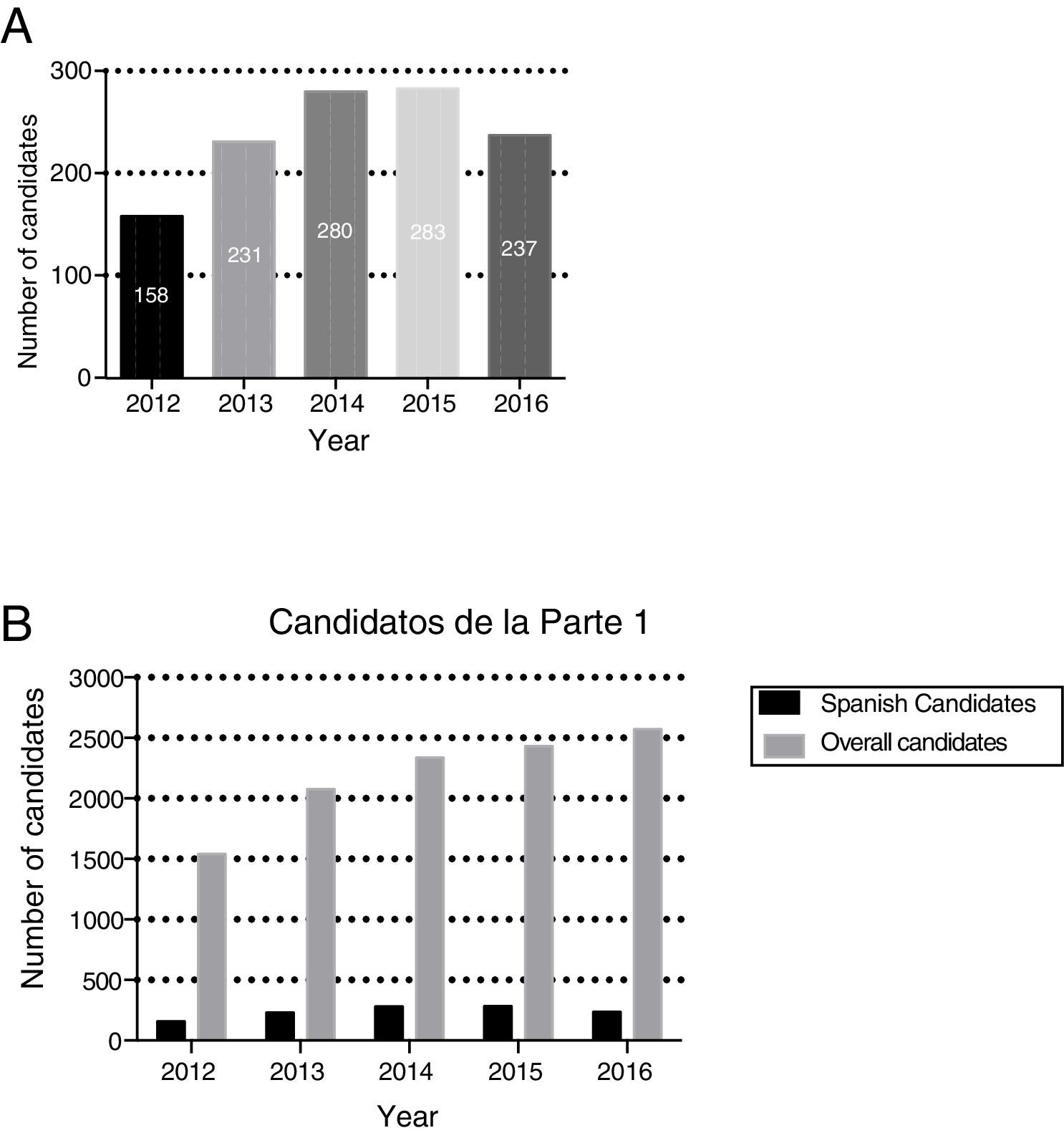

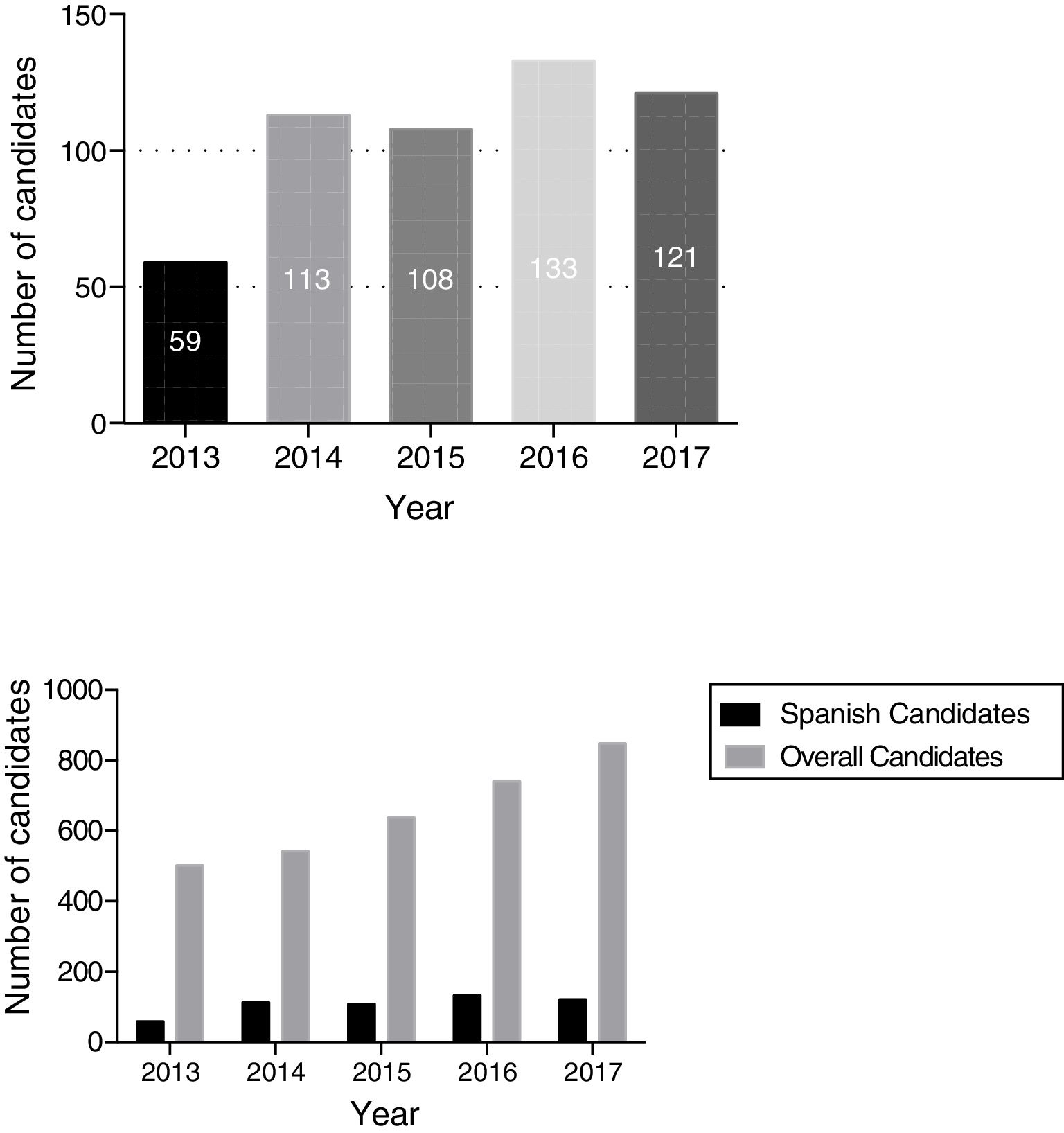

ResultsBetween 2012 and 2016, Spanish centres accounted for 1189 (10.85%) of the total of 10,954 candidates who registered for Part 1 of the exam worldwide. The annual number of candidates increased between 2012 and 2014 from 158 to 280 candidates, and stabilized from 2015, with between 237 and 283 candidates per year (Fig. 1A). This evolution followed the trend of growth of the exam in the rest of the world (p=0.29) (Fig. 1B).

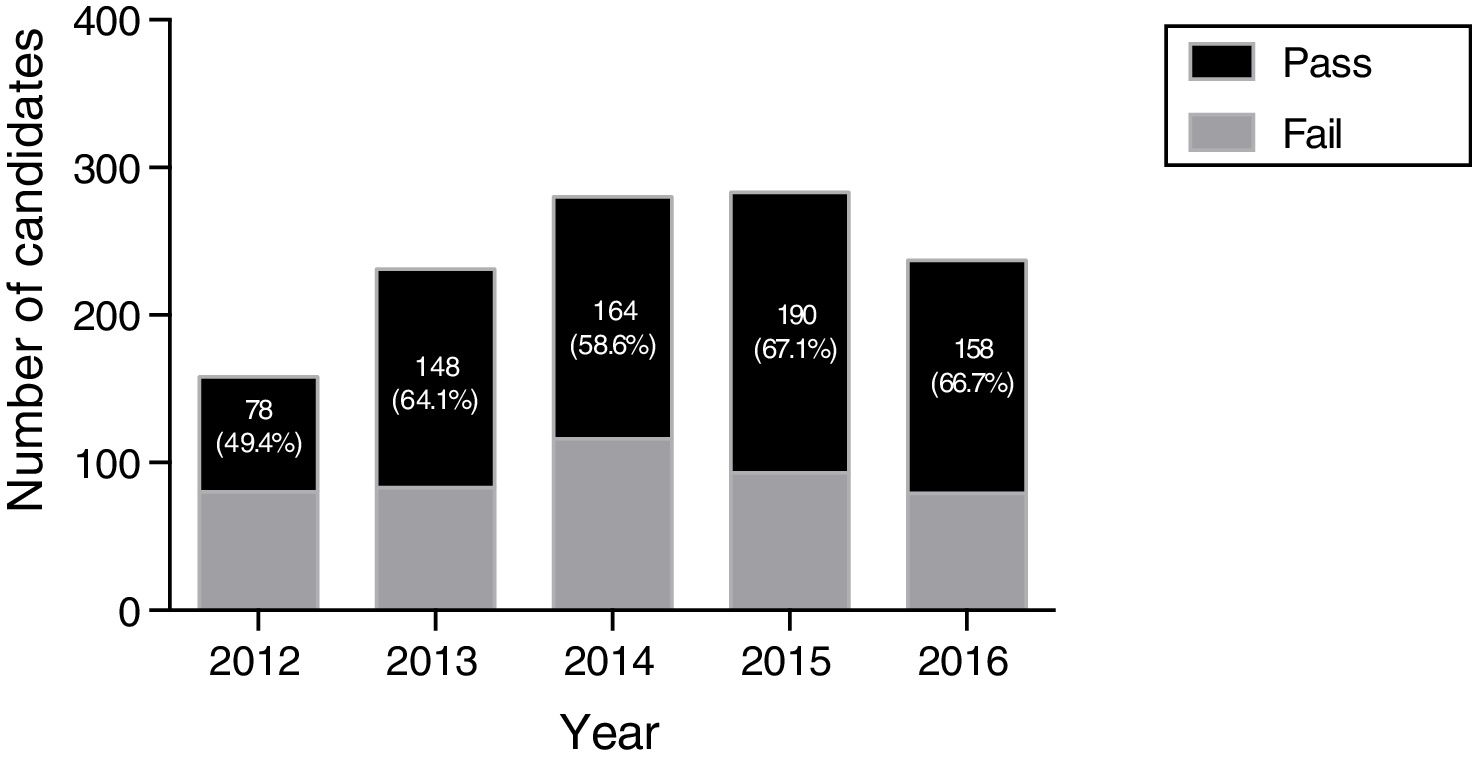

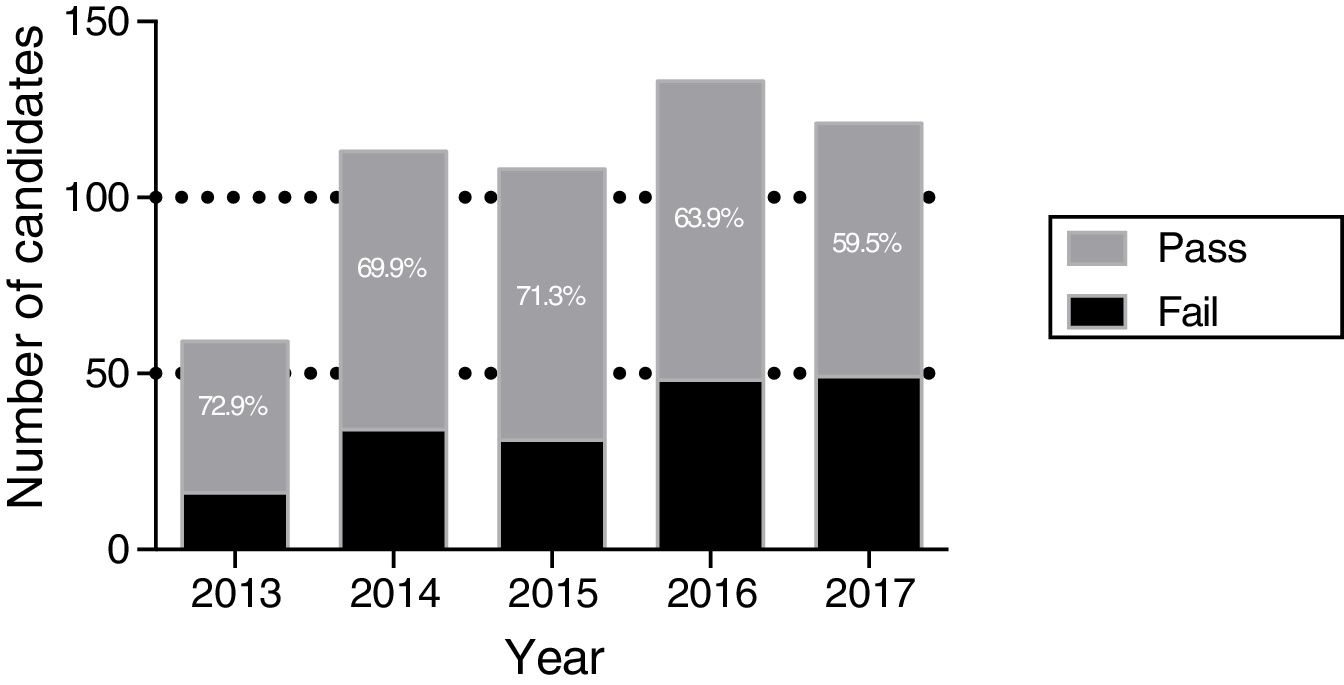

Of the 1189 candidates sitting Part 1, 738 (62.1%) passed and were allowed to take Part 2. The pass-rate varied significantly between years in this period (p<0.001), with a median value of 64.1% (range [49.4%; 67.1%]), and a consolidated higher score in the last 2 years of the study, as shown in Fig. 2. Those results did not differ significantly from candidates from the rest of the world, whose median pass rate was 57.9% (range [55.9%; 59.9%]) over the same period (p=0.38).

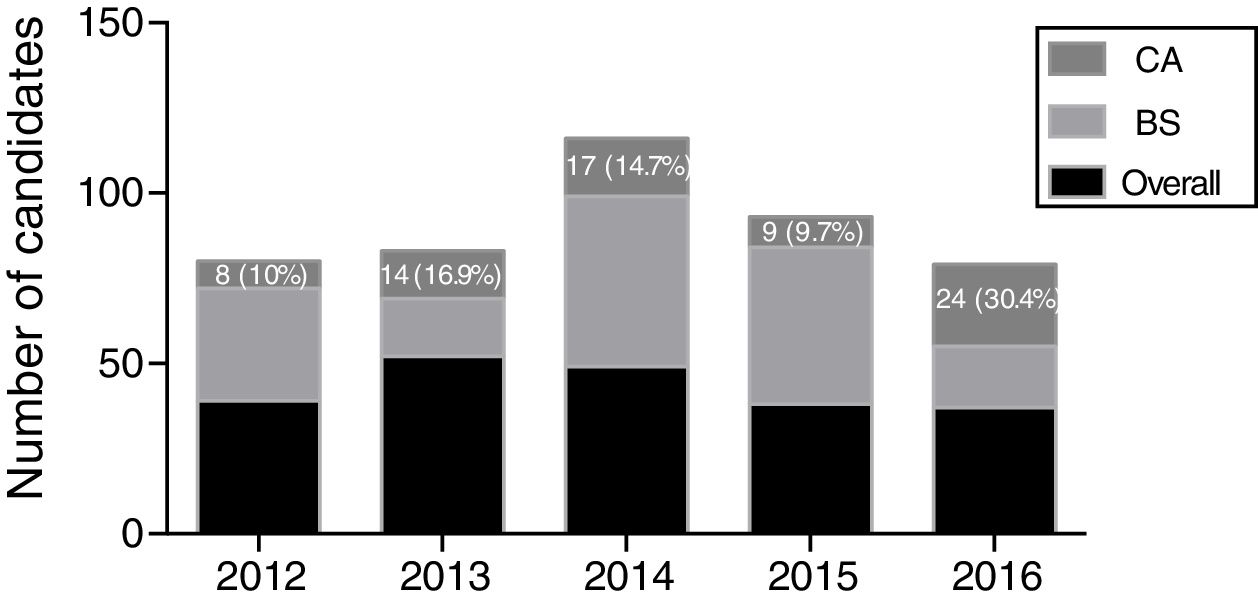

Of the 451 (37.8%) candidates that failed, 215 (47.7%) failed in both basic sciences and clinical anaesthesiology, 164 (36.4%) only in basic sciences, and 72 (15.9%) only in clinical anaesthesiology. Failures due only to the clinical anaesthesiology exam were significantly different between years (p=0.01), but never represented more than 30.4% of failed candidates (Fig. 3).

Mean scores were 71.74±5.98% for paper A and 74.48±4.29% for paper B, with significant variations between years for both papers (p<0.001 and p=0.001 respectively). Yearly mean values ranged from 69.03 to 74.9% for paper A and from 73.55 to 75.02% for paper B, but these results followed the trend in other countries, since the pass rate followed the trend of the other candidates worldwide.

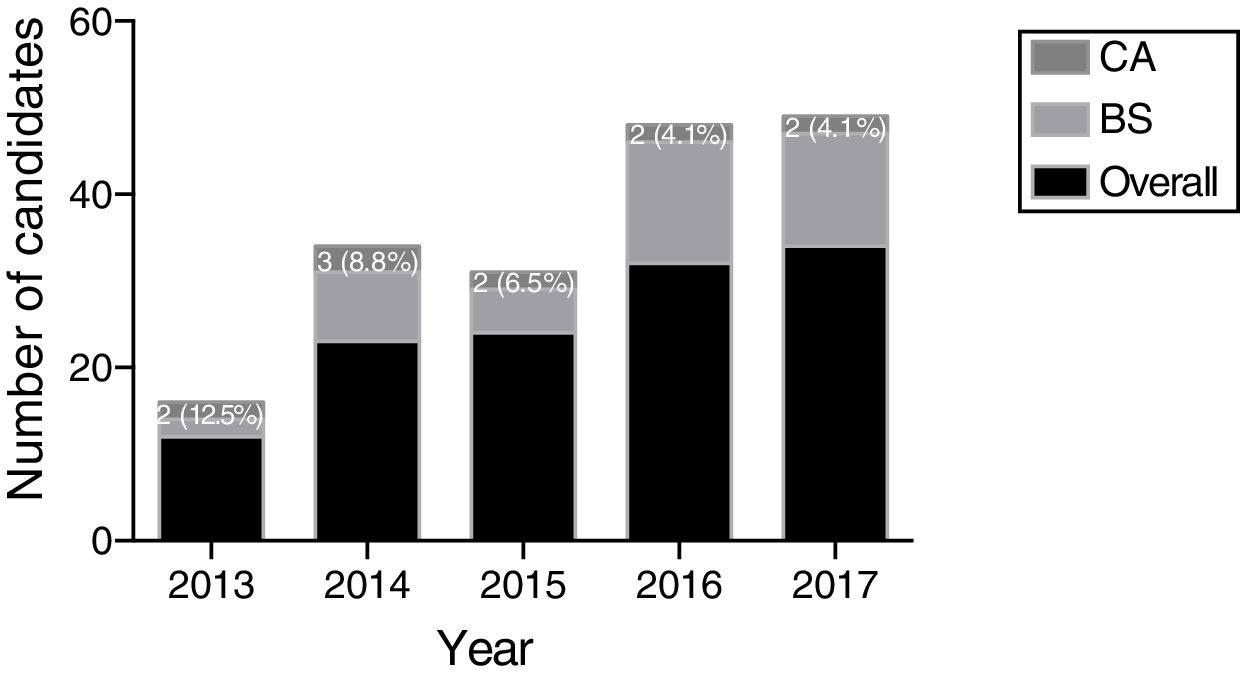

Between 2013 and 2017, 534 (72.4%) of the candidates who had passed Part 1 sat for the Part 2 in Spanish centres, which represented 16.3% of the total candidates sitting the Part 2 in this period worldwide (Fig. 4). Three hundred and thirty-five (62.7%) passed and received the EDAIC diploma, versus 1701/2736 (62.2%) in the rest of the world (p=0.91) (Fig. 5). Median pass rate was 69.9% (range: [59.5%; 72.9%]), with no significant difference with results from the rest of the world. Candidates’ yearly median pass rate of 64.9% (range: [57.8%; 67.7%]) did not differ significantly from the rest of candidates (p=0.22). The number of diplomates stabilized at about 70 per year, in parallel with the trend observed in candidates from the rest of the world (p=0.67). Over the study period, 49 (14.6%) of the candidates who passed obtained at least two 2+ marks in Part 2, demonstrating a high level of knowledge, with no significant change between years (p=0.19).

Of the 178 candidates who failed, 125 (70.2%) had at least 1 narrow fail in o1 ne basic sciences viva and 1 clinical viva, 42 (23.6%) failed due to the basic sciences vivas, and 11 (6.2%) the clinical anaesthesiology vivas, indicating again that basic sciences were implicated in almost 95% of failing candidates, and clinical anaesthesiology in almost 30%. Bad fails partly accounted for the failure of 56 candidates (31.5% of the cases), but isolated bad fails in 1 viva only occurred in 7 (3.9%) candidates during the period of study, showing the infrequency of specific knowledge deficits. The incidence of bad fails was 8.3% (5.6%; 15.8%), with no significant difference between years (p=0.06). Thirty six (64.3%) bad fails occurred in basic sciences vivas, versus 16 (28.6%) in clinical anaesthesiology and 4 (7.1%) in both basic sciences and clinical anaesthesiology vivas, with no significant change during the period assessed (p=0.09). Concerning the causes of failure, no significant difference was observed between years for Part 2 of the exam (p=0.77) (Fig. 6).

DiscussionThe results presented in this study, showed a significant increase in the number of candidates for the 2 parts of the EDAIC exam, and an increasing number of ESA (DESA) diplomates in Spain, mirroring the evolution worldwide. A stabilization at 250 candidates per year for Part 1 in Spain would be a reasonable expectation for the future, which would correspond to 80% of the 300–320 residents trained in Anaesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Management each year,9 since by now most of those experienced anaesthesiologists who did not sit the EDAIC during their training period have already passed the EDAIC, or have decided not to sit it in the future. This expansion of the EDAIC in Spain has also recently been reported in other countries, such as Germany.4 This could reflect a global change in mentality among anaesthesiology trainees, who see it as useful and worthwhile to obtain a validation of their knowledge at the end of their post-graduate training programme, even when this evaluation is not mandatory in their country, in order to be able to show that they have reached the standards of excellence recommended by the EBA and the UEMS.6

The fact that 27.6% of candidates who passed Part 1 did not register for Part 2 is not surprising in the specific context of Spain. This country has a very limited culture of oral examination: in many Spanish medical schools this method of evaluation is uncommon, and anaesthesiologists are not at all at ease with it. As a result, many candidates consider Part 2 to be exhausting and extremely challenging, and almost one third prefer not to undergo this ordeal. Very few centres train their residents for this last step towards achieving this mark of excellence in anaesthesiology. Despite this, more than 60% of those who sat the exam managed to pass. Better training in oral examination techniques, such as that give in other countries,10 would probably boost the self-confidence of candidates who pass Part 1, and this could increase the rate of registration for Part 2 and improve the pass rate.

In terms of pass/fail results, candidates in Spanish centres did not perform differently from those in other countries. This is an encouraging trend, and shows that the high standard of the EDAIC remained applicable to Spanish centres over the past 5 years: around 60% of the best prepared candidates passed each stage of the exam, and 15% of them even obtained a high score in Part 2, with more than two 2+ marks. The absence of formal evaluation of knowledge at the end of their residency programme,8 and the shorter duration of training of Spanish anaesthesiologists compared with most European countries,2,11 did not seem to give Spanish candidates a disadvantage over candidates from the rest of the world: a similar level of theoretical preparation lead to similar results in Part 1 and Part 2. However, our results probably do not reflect the level of all Spanish residents: the level of those residents who did not sit the EDAIC exams are not included here, since the EDAIC is not mandatory. Moreover, the results we present in this study concern mostly Spanish candidates, but also include a small number of non-Spanish candidates who took the exam in a Spanish centre, and this limits their interpretation.

The pass rate among candidates sitting Part 1 or Part 2 did not change significantly over the period of the study, despite an increase in their number. This stable level of preparation among candidates was probably partly due to the increasing number of ESA diplomates among Spanish anaesthesiologists who encourage and advise younger colleagues in their preparation for the EDAIC exams. In fact, in recent years, local preparatory sessions were organized in teaching hospitals, and even specialized courses to prepare for the EDAIC examinations have become available.12–16 Moreover, an increasing number of training and learning tools have also been developed by the ESA for its members to help trainees acquire high quality knowledge and prepare for the exam. These include the e-learning programme,17 the Basic Sciences Anaesthetic Course (BSAC),18 and the On-Line Assessment (OLA),4,19 although many residents may still be unaware of these tools, because little has been done to promote them so far.20

A constant for both Part 1 and Part 2 of the exam is that basic sciences is implicated in 84.1% and 93.8% of failures, respectively, showing that these candidates are poorly prepared in what could be considered indispensable background knowledge for our speciality. Similar pass rates in Spain and the rest of the world suggest an insufficient level of preparation in most countries. Knowledge in basic sciences is difficult to acquire, and scores for this topic could be improved by helping candidates prepare themselves with local courses, which have been shown to improve results in EDAIC Part 1,13 or international courses organized by the ESA, such as the BSAC, which is highly rated by trainees (unpublished data).

This study presents various limitations that could be addressed in future projects: not all the candidates examined in Spanish centres were Spanish or living in Spain (especially for Part 2 of the exam), so more discriminate data collection concerning candidates performing their training in Spain could be more accurate.

Marks for Part 1 of the exam varied between years, and the pass mark was adapted accordingly to apply a correction. This correction is based on an analysis of reference/discriminator questions that reflect the performance of candidates, using a Gaussian analysis of the results. It takes into account 2 important variables:

The use of new and existing MCQs each year can result in slight variations in the marks of the papers.

The level of the groups of candidates may vary between years. It would be unfair to fail candidates simply because they obtained lower marks in a particularly strong year, while his/her results were comparatively better in a weaker group of candidates.

Hence, it is difficult to compare the real level of candidates between years by merely comparing marks.

Finally, we did not perform individualized follow-up of candidates. This prevented us from analysing their trajectory, whether they registered once or multiple times for the different parts of the exam, whether they let some time pass between sitting Part 1 and Part 2, and the profile of those who decide against sitting Part 2 after passing Part 1. A more precise description could help improve the preparation of future candidates and increase participation and scores.

Training in anaesthesia covers various dimensions. Knowledge is perfectly assessed in the EDAIC. This should be the standard in all European countries, and has showed significant expansion in recent years in both Spain and the rest of Europe. This initiative participates actively in the harmonization of knowledge among European anaesthesiologists. Moreover, medical accreditation will probably soon be oriented towards more competence-based systems. In this respect, the EBA has recently published new European Training Requirements in Anaesthesiology,7 which include domains of knowledge and competences that an anaesthesiologist should acquire during his training, which they recommend should not last less than 5 years. Evaluation systems are needed to verify acquisition of these competences.2 The evolution of the EDAIC, together with new marking systems, technological improvements with computer-based assessments, and the development of other evaluation tools for technical and non-technical skills would be beneficial to harmonize the evaluation of competences in our specialty. In our opinion, the European Society of Anaesthesiology is best equipped to drive through these changes.

Since the beginning of the economic crisis at the end of the first decade of 2000, existing migration patterns of European medical doctors, increased exponentially in Spain,21 and in order to meet European standards, supra-national institutions must help national authorities define and design training and evaluation programmes for specialists.

Conflicts of interestNone to declare.

We would like to thank the ESA secretariat (Iwona Darquenne, Rodolphe Di Loreto, Mary Fay, Odile Jacquet, and Hugues Scipioni) for their remarkable work and their help in the collection of the data.

Please cite this article as: Brogly N, Engelhardt W, Hill S, Ringvold E-M, Varosyan A, Varvinskiy A, et al. Diploma Europeo en Anestesiología y Cuidados Intensivos en España: resultados de los exámenes de las partes 1 y 2 de los últimos cinco años. ¿Vamos por el buen camino?. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2019;66:206–212.