Musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) are the second leading cause of disability worldwide. There are difficulties in the early diagnosis and therapeutic approach to these pathologies, with a negative impact on their outcomes. Access to rheumatology is limited, with a low supply in the face of growing demand, which makes the general practitioner the first contact for care.

ObjectivesDescribe the perception and confidence that general practitioners have regarding the training in rheumatology received at undergraduate level.

Materials and methodsObservational cross-sectional study, with a Likert-type survey tool being used. The study included general practitioners graduated from the Colombian Medicine program between 2009 and 2019. The variables studied were those related to the curriculum, acquired knowledge or skills, and proficiency in content in rheumatology compared to practice. Subjects who attended a specialist or who had an employment relationship with a specialist rheumatology centre were excluded.

Results and ConclusionsA total of 102 physicians were surveyed, and 86 completed questionnaires were included in the final analysis. Of these, 83.4% were graduates of private universities. Over two-thirds (37%9) had a formal subject in rheumatology, 16% received training with specific strategies, 54% expressed security when performing the MS physical examination, and 47% were sure in the diagnostic approach, and prescription of disease-modifying drugs. In order to strengthen the training in rheumatology required by the undergraduate, a joint effort is required with the medical schools in defining the competencies and skills of the primary care physician, together with the health needs and available educational strategies.

Las enfermedades musculoesqueléticas (EM) son la segunda causa de discapacidad mundial. Se presenta dificultades en el enfoque diagnóstico y terapéutico temprano de estas patologías, lo cual tiene un impacto negativo en sus desenlaces. El acceso a reumatología es limitado, con una baja oferta frente a la creciente demanda, lo que convierte al médico general en el primer contacto de atención.

ObjetivosDescribir la percepción y la confianza que tienen los médicos generales respecto a la formación en reumatología recibida en el pregrado.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional de corte transversal en el cual se indagó a médicos generales, egresados de programas de medicina colombianos entre el 2009 y 2019, mediante un cuestionario con respuesta tipo Likert, sobre variables relacionadas con el planteamiento curricular, los conocimientos o habilidades adquiridas y la suficiencia en el contenido en reumatología con respecto a la práctica. Se excluyeron sujetos que cursaran algún programa de especialización o que tuvieran relación laboral con un centro especializado de reumatología.

Resultados y conclusionsSe encuestó a 102 médicos, 86 encuestas fueron incluidas en el análisis final. El 83,4% eran egresados de universidades privadas, el 37% contó con una asignatura formal de reumatología, el 16% recibió formación con estrategias específicas, el54% manifestó seguridad al realizar el examen físico ME, el 47% expreso sentirse seguro en el enfoque diagnóstico y la prescripción de medicamentos modificadores de la enfermedad. Es necesario fortalecer la formación en reumatología en el pregrado, se requiere un trabajo conjunto con las facultades de medicina en la definición de competencias del médico de atención primaria, alineado con las necesidades de salud y las estrategias educacionales disponibles.

Musculoskeletal diseases (MSDs) are the most common cause of long-term chronic pain,1 they constitute the second most frequent cause of disability in the world (measured by years of life lived with disability),2 and an increase in the prevalence and impact in the population in developing countries is predicted.3,4 Unfortunately, there are difficulties in the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of these patients, there is low resolution in the first levels of care and an insufficient offer of Rheumatology services.5–7 These difficulties have a negative impact on the prognosis of the diseases and lead, in some scenarios, to structural and irreversible damage and to higher direct and indirect costs.8

According to data found in the Higher Education Information System (SNIES, for its acronym in Spanish, Sistema de Información de la Educación Superior), in Colombia there are 63 active undergraduate programs in Medicine, offered by 50 higher education institutions. Likewise, there are 97 postgraduate programs, offered by 31 higher education institutions, among which are medical-surgical specialties that are divided, in turn, into first specialties (those that require a general medical degree) and second specialties (those that require a previous medical-surgical specialty degree).9 Between the years 2001 and 2014, approximately 49,224 general practitioners graduated in Colombia, with an average of 3516 per year.

In total, 14,805 specialists graduated between the years 2001 and 2014, with an annual average of 1057 and an average growth of 2.4%, of whom 2637 were specialists in Internal Medicine.10–12 As for the specialization in Rheumatology, Colombia has 8 postgraduate programs, offered by 8 higher education institutions in the national territory.9 The American College of Rheumatology recommends that for every 100,000 inhabitants there should be 1.1 rheumatologists. According to this reference, Colombia should have 546 rheumatologists. Currently, there are approximately 40% of the number of specialists proposed.7,10

Considering the international and national panorama of prevalence of musculoskeletal problems in the general population,13,14 as well as the scarce training in Rheumatology during the university undergraduate program of Medicine, in addition to the barriers to be admitted to a medical-surgical post-graduate program in the country,6,10 it becomes necessary to evaluate the clinical competencies developed by the general practitioners in the approach of musculoskeletal problems15–18 and their perceptions about the acquired knowledge, since they are the Primary Care professionals with whom, in the first instance, the population affected by these diseases will have contact.19

This study presents the perception that a sample of general practitioners from different faculties of the country has about the training they received in Rheumatology during the undergraduate medical program, as well as the implication in the daily professional practice. Knowing these perceptions is a first step for identifying the strengths, the barriers and the aspects to be improved in the curricula of the different faculties of Medicine, seeking to generate initiatives that favor the strengthening of training in Rheumatology for both undergraduate programs and for permanent or continuing education activities.20,21

Materials and methodsObservational cross-sectional study in which a survey was designed by a group of rheumatologists, a specialist in medical education, and an epidemiologist. The group was in charge of designing the instrument; an initial pilot was carried out in 30 subjects, with subsequent adjustment of the final instrument (Appendix B, see the Annex).

General practitioners graduated from medicine programs in Colombia between 2009 and 2019 were included; subjects who were studying a specialization program or with current or past work activity related to a specialized Rheumatology center were excluded. A non-probability convenience sampling was carried out. Through social networks, Email and in person, approximately 200 doctors were invited to participate, of them, 102 responded.

The professionals included in the study are graduates from the following universities: Universidad Libre seccional Barranquilla, Universidad de Antioquia, Universidad del Rosario, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Universidad de Los Andes, Universidad de La Sabana, Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de La Salud, Fundación Universitaria Juan N. Corpas, Fundación Universitaria San Martín, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Universidad El Bosque, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana campus Bogotá and Cali, Universidad de Ciencias Aplicadas y Ambientales, Universidad del Cauca, Unisanitas, Universidad Metropolitana, Universidad del Valle and Universidad del Magdalena.

The information was collected electronically; The variables analyzed included: demographic data (university, year of graduation, field of professional practice), variables related to the curricular approach (chair or subject of Rheumatology, rotation in Rheumatology, workshops or seminars, knowledge of the gait, arms, legs, spine [GALS] strategy,1 procedures), variables related to acquired knowledge or skills (perception of security and confidence in the interrogation, physical exam, beginning of treatment, prescription of analgesia, steroidal antiinflammatory drugs or disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and sufficiency in rheumatology content with respect to the professional practice). A complete descriptive analysis with frequencies (absolute and relative) and percentages was carried out using the SPSS20 program licensed by the University of La Sabana (Universidad de la Sabana).

Results102 physicians participated, of whom 60.7% were women, with a mean age of 30.1 years. Of them, 16 participants did not meet the inclusion criteria, since they graduated before 2009, and for this reason they were excluded from the subsequent analysis.

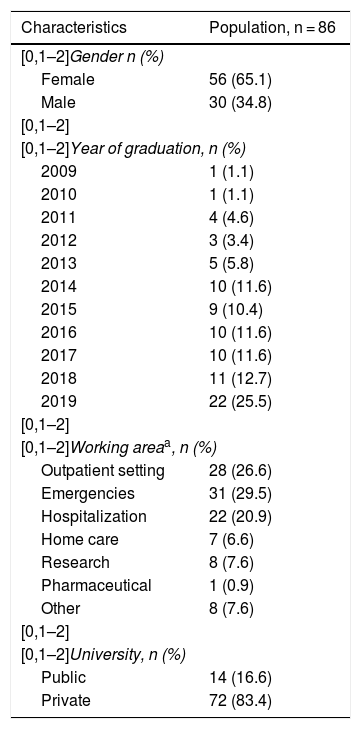

Of the 86 final participants, 83.4% of the physicians were practicing general medicine since 2014. Of the total sample, public universities accounted for 16.6% and private universities for 83.4%. Regarding the place where they worked, 26.6% were in the outpatient setting, 29.5% in the emergency department, 20.9% in hospitalization, 6.6% in home care, 0.9% in the pharmaceutical industry, 7.6% in research and the same percentage worked in other areas (Table 1).

Characteristics of the population.

| Characteristics | Population, n = 86 |

|---|---|

| [0,1–2]Gender n (%) | |

| Female | 56 (65.1) |

| Male | 30 (34.8) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Year of graduation, n (%) | |

| 2009 | 1 (1.1) |

| 2010 | 1 (1.1) |

| 2011 | 4 (4.6) |

| 2012 | 3 (3.4) |

| 2013 | 5 (5.8) |

| 2014 | 10 (11.6) |

| 2015 | 9 (10.4) |

| 2016 | 10 (11.6) |

| 2017 | 10 (11.6) |

| 2018 | 11 (12.7) |

| 2019 | 22 (25.5) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Working areaa, n (%) | |

| Outpatient setting | 28 (26.6) |

| Emergencies | 31 (29.5) |

| Hospitalization | 22 (20.9) |

| Home care | 7 (6.6) |

| Research | 8 (7.6) |

| Pharmaceutical | 1 (0.9) |

| Other | 8 (7.6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]University, n (%) | |

| Public | 14 (16.6) |

| Private | 72 (83.4) |

Regarding the description of the educational content, only 37% of the faculties had in their study plan a formal chair or subject with topics of Rheumatology. 60% received master classes or formal workshops related to MS diseases and the same percentage received a class or workshop related specifically to the musculoskeletal physical examination. Only 16% received training in the GALS strategy, while 63% considered that they did not have a good academic training in Rheumatology. About the physical evaluation of a patient with suspected MS disease, 34% said that they felt somewhat sure, and 20% sure, so that 54% of the participants expressed confidence at the time of examining this type of patients.

On the other hand, only 30% had the opportunity to rotate through the Rheumatology service and only 10% performed some related procedure, such an arthrocentesis. When asked on the certainty and confidence at the time of the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with suspected MS disease, 46% stated that they were sure, 33% neutral and 20% does not feel sure at all when focusing on these patients. The confidence in the prescription of analgesics with some degree of security was 80%, while 20% indicated that they felt neutral or not at all sure of their prescription. In contrast, 53% were not sure at all regarding the capability to prescribe DMARDs, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and leflunomide.

Of the 86 physicians included in the study, 74 (86%) considered that knowledge in the area of Rheumatology is a topic relevant for their professional performance. The interest in specialties such as Orthopedics, Physiatry and Rheumatology was 66%.

DiscussionThe present study shows that only 37% of the respondents had a formal undergraduate Rheumatology course, 16% received training in GALS strategy or know it, 54% are confident when examining patients with musculoskeletal symptoms, 46% express security in the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of these patients and 47% feel sure when they prescribe DMARDs. Therefore, the situation put into evidence is worrying, in which the presence of the teaching of Rheumatology in Primary Care physicians, the perception of security and confidence when facing these patients and the certainty in the prescription of disease modifying drugs is present in less of 50% of the surveyed physicians.

This is not an exclusive situation of Colombia, in the Congress of the American College of Rheumatology, 2015, the results of a study of a group of 320 physicians of Latin American Countries who were surveyed on their perception of the education in Rheumatology were published, and these results made evident that only 29.1% of the medical schools teach Rheumatology in the undergraduate curriculum. 72% consider that the physicians of the region are not sufficiently prepared for the care of rheumatic diseases or they know little, while 67% think that the training provided by their own institution or university is deficient.22

Rheumatic diseases have a great impact on the quality of life of the patients due to the chronic pain and disability they generate.4,23 In the inflammatory rheumatological diseases, it has been shown that early initiation of treatment (ideally within the so-called window of opportunity) determines the therapeutic response, the progression of organ damage and, therefore, the prognosis. Unfortunately, the initial approach and management of patients is not always adequate. On the one hand, access to clinical evaluation by a specialist in Rheumatology is often not timely. It has been described that the proportion of patients who can be evaluated 6 weeks after the onset of symptoms by this specialty is between 6 and 17%.24

The pivotal period to start a DMARD in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), for example, are the first 12 weeks since its diagnosis25,26 and in a study with 527 patients with a recent diagnosis of RA it was found that the first visit to a rheumatologist after the onset of the symptoms was at 17 months and the initiation of the DMARD was at 19 months.27 A model of supply/demand of rheumatologists with data from the United States predicts an excess in the demand for these specialists, considering the increase in the longevity of the population, the incidence of this type of diseases and the fact that the number of rheumatologists in training is not proportional, which is why a call is made to redesign clinical practice, to expand the knowledge of these diseases, to implement new processes that are more effective so that the clinician has better resolution tools, ensuring a better control thereof and, concomitantly, contributing to the control of their costs.28

In a British observational study with 1624 undergraduate students and 2700 professors of Rheumatology in the undergraduate program, 90% of the first group manifested that they had received training in Rheumatology in their undergraduate program and cataloged it as irrelevant, while 28% of the second group expressed that they had additional training previously to the exercise of their profession.29 In another study, in which 251 physicians participated, 77% reported having a specific chair of Rheumatology during undergraduate training, of them, only 19% had sufficient skills to treat this type of patients.30 In Australia, the group of Crotty et al. explored the level of knowledge, experiences and clinical practices, skills and attitudes towards patients with rheumatic disease in 382 medical interns from 12 different hospitals in the country.31

A considerable degree of dissatisfaction related to the teaching of the approach and the treatment of patients with rheumatic diseases was observed; only 22% considered that the education provided had been good or excellent.31 As for the psychosocial dimension of the disease, it was observed that only 32% of the medical interns consulted had received education in the management of this dimension in patients with chronic rheumatic diseases and only 22% were able to evaluate and treat the psychosocial aspect of the disease in terms of disability.31 The limited availability of time that specialists have to dedicate to teaching, the factors of institutional organization involved, the lack of standardization regarding the examination of the musculoskeletal system, both in learning and in daily practice, as well as their little applicability, were mentioned among the barriers that were found for the correct learning of Rheumatology during the undergraduate medicine program.32

Weaknesses in competencies related to musculoskeletal physical examination have also been reported.33 During the routine physical examination, not much attention is paid to the exploration of the locomotor system, possibly as a consequence of the limited time between patients, or because it is considered so complex that it is decided to overlook it. The GALS was developed as a simple, practical and sensitive tool as a screening test of the MS system. Depending on the findings, a more specific exam is performed. However, the GALS as a standardized method for teaching the musculoskeletal exam is only used by a third of the professors on a regular basis, the other 2 thirds either do not apply it or are unaware of it.34

A study also conducted in the United Kingdom in 2014 assessed the state of education provided to undergraduate medical students from the areas of Rheumatology and Orthopedics for the approach of musculoskeletal problems, as well as the strategies used. The study included 47 (61.8%) specialists in Rheumatology and 29 (38.2%) specialists in Orthopedics, of whom 50% stated that they use the GALS as a teaching method.32 When the groups were analyzed separately, it was found that 76.6% of the rheumatologists consulted use the GALS as an educational method and only 6.9% of the orthopedists consulted use it in their educational practice. The reasons by which the respondents claimed not to use the GALS as a teaching method included the lack of experience in its use (56.5%) and the preference for a more complete regional examination technique (31.6%).

The limitations of this study include its observational nature. In addition, it has a small sample and the curricula of the universities of the respondents, as well as the methods of teaching and learning are unknown. However, its results invite to reflection and to the generation of effective teaching strategies, to the search for new horizons in the formation and training in MS diseases, focusing efforts on undergraduate medicine, since optimizing and adapting the characteristics of higher education to the needs of the society through practical learning will impact the appropriate approach to these patients and an optimal pharmacological prescription, which will result in better clinical outcomes.35 It has been demonstrated that the application of care models articulated to educational strategies generates a positive impact on the evolution and, finally, on the cost of these diseases.36

ConclusionIt is necessary to work together with the Faculties of Medicine in the definition of the competencies that a general practitioner must achieve in Rheumatology, aligned with the health needs of the population and the educational strategies available.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors do not have any conflict of interest for the development of this work.

Please cite this article as: Mora Karam C, Beltrán A, Restrepo J, Sierra R, Guerrero YA, Martinez DC. Educación y reumatología en el pregrado: ¿enseñamos suficiente? Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2022;29:38–43.